Abstract

Purpose

To assess the levels of quality of life (QoL) in major depressive disorder (MDD) patients treated with either duloxetine or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) as monotherapy for up to 6 months in a naturalistic clinical setting mostly in the Middle East, East Asia, and Mexico.

Patients and methods

Data for this post hoc analysis were taken from a 6-month prospective observational study involving 1,549 MDD patients without sexual dysfunction. QoL was measured using the EQ-5D instrument. Depression severity was measured using the Clinical Global Impression of Severity and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR16), while pain severity was measured using the pain items of the Somatic Symptom Inventory. Regression analyses were performed to compare the levels of QoL between duloxetine-treated (n=556) and SSRI-treated (n=776) patients, adjusting for baseline patient characteristics.

Results

These MDD patients, on average, had moderately impaired QoL at baseline, and the level of QoL impairment was similar between the duloxetine and SSRI groups (EQ-5D score of 0.46 [SD =0.32] in the former and 0.47 [SD =0.33] in the latter, P=0.066). Both descriptive and regression analyses confirmed QoL improvements in both groups during follow-up, but duloxetine-treated patients achieved higher QoL. At 24 weeks, the estimated mean EQ-5D score was 0.90 in the duloxetine cohort, which was statistically significantly higher than that of 0.83 in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001). Notably, pain severity at baseline was also statistically significantly associated with poorer QoL during follow-up (P<0.001). In addition, this association was observed in the subgroup of SSRI-treated patients (P<0.001), but not in that of duloxetine-treated patients (P=0.479).

Conclusion

Depressed patients treated with duloxetine achieved higher QoL, compared to those treated with SSRIs, possibly in part due to its moderating effect on the link between pain and poorer QoL.

Keywords: depression, antidepressant, duloxetine, SSRI, quality of life

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly prevalent mental disorder that is associated with significant levels of disability, morbidity, and mortality. It is one of the leading causes of disability globally, affecting nearly 350 million people worldwide,1 and the burden associated with MDD continues to increase.2 The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study, for instance, showed a 37% increase in disability-adjusted life years due to MDD between 1990 and 2010.2 MDD is also known to have a major impact on health-related quality of life (QoL) and functioning. For example, a previous study by Rapaport et al3 reported that approximately 63% of patients with MDD and 85% of patients with chronic/double depression (ie, an MDD episode on top of dysthymia) entering clinical trials had severe QoL impairments.

Several studies have shown that impairments in QoL and functioning often persist beyond the clinical resolution of depressive symptoms,4 placing patients at an increased risk of relapse and leading to higher direct and indirect costs.5 Notably, the severity of depressive symptoms has been found to explain only partially the impairment of QoL.3,4,6–8 This suggests that assessing depressive symptoms alone may not be sufficient to measure the success of MDD interventions.7 There is thus a growing interest in complementing traditional symptom measures with additional QoL measures when evaluating treatment effectiveness.8,9

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are two classes of antidepressants with a better safety profile than older treatments, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, or the monoamine oxidase inhibitors.10–12 SSRIs and SNRIs are also recommended as first-line treatments for MDD by several international guidelines, such as those issued by the American Psychiatric Association,10 the British Association of Psychopharmacology,11 and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments,12 for example.

While treatment for MDD has been shown to improve QoL,8 there is scant available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of SNRIs and SSRIs that is based on a formal assessment of QoL outcomes. The evidence on their comparative effectiveness in terms of symptom improvement is also limited and inconclusive.13–16 Nevertheless, emerging evidence suggests that SNRIs, including duloxetine, may have additional advantages for patients with concurrent pain and depression.13,14,17 Depression and pain are common comorbidities.18 Previous research has shown that the coexistence of these two conditions greatly impacts clinical outcomes, functioning, and QoL.19 It has been suggested that the dual action of SNRIs may be more effective than those that inhibit only one monoamine, at least for patients suffering from both depression and pain,13,14,17 given the hypothesis that the pathophysiology of both conditions involves an imbalance of serotonin and norepinephrine.18

Duloxetine hydrochloride is a potent and relatively balanced inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake.20 It has been approved for the management of MDD, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, and chronic musculoskeletal pain in the United States, and for some or all of these indications in many countries worldwide. In line with these indications, the findings from clinical trials have shown that treatment with duloxetine improves pain and that this further helps to improve the outcomes of depression.21–23 Such findings have been poorly documented for the SSRIs however.24–26

Using data from a 6-month prospective observational study conducted mostly in East Asia, the Middle East, and Mexico, this post hoc analysis aimed at examining the comparative effectiveness of duloxetine versus an SSRI on QoL in the treatment of MDD in a naturalistic clinical setting in non-Western countries. In addition, this study examined the impact of pain on the QoL outcomes. It examined whether the comparative effectiveness of duloxetine versus an SSRI differ between patients with and without painful physical symptoms (PPSs) at baseline; and whether baseline pain severity influences QoL improvements, and if so, whether this association varies with the type of treatment.

Patients and methods

Study design

Data for this post hoc analysis were taken from a 6-month, international, prospective, noninterventional, observational study, primarily designed to examine treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction (TESD) and other treatment outcomes among patients with MDD who were treated with either an SSRI or an SNRI in actual clinical practice. A total of 1,647 patients were enrolled at 88 sites between November 15, 2007 and November 28, 2008. Of these, 1,549 patients were classified as “sexually active patients without sexual dysfunction at study entry” and were included in the study. The patients were drawn from the following regions and countries across the globe: East Asia (People’s Republic of China [n=205; 13.2%], Hong Kong [n=18; 1.2%], Malaysia [n=33; 2.1%], the Philippines [n=113; 7.3%], Taiwan [n=199; 12.8%], Thailand [n=17; 1.1%], and Singapore [n=2; 0.1%]), the Middle East (Saudi Arabia [n=179; 11.6%] and United Arab Emirates [n=135; 8.7%]), Mexico (n=591; 38.2%), and other regions (Israel [n=9; 0.6%] and Austria [n=48; 3.1%]). This study followed the ethical standards of responsible local committees and the regulations of the participating countries, and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and are consistent with Good Clinical Practice where applicable to a study of this nature. Ethical Review Board approval was obtained in each of the 12 participating countries as required for observational studies wherever required by local law. All patients provided written informed consent for the provision and collection of the data. Further details of the study design have been published elsewhere.27,28

Study population

Patients (outpatients) were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) presenting with an episode of MDD within the normal course of care, with MDD diagnosed according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 10th revision29 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition text revision30 criteria; 2) at least moderately depressed, defined by the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) (with a score of ≥4);31 3) initiating or switching to any available SSRI or SNRI antidepressant in any of the participating countries, in accordance with a treating psychiatrist’s discretion; 4) at least 18 years of age; 5) sexually active (with partner or autoerotic activity, including during the 2 weeks prior to study entry) without sexual dysfunction, as defined by Arizona Sexual Experience Scale;32 6) not participating in another currently ongoing study; and 7) providing consent to release data. The study excluded the patients who had: 1) a history of treatment-resistant depression (defined as failure to respond to treatment with two different antidepressants from different classes at therapeutic doses for ≥4 weeks33); 2) a past or current diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, mental retardation, or dementia; or 3) received any antidepressant within 1 week (1 month for fluoxetine) prior to study entry, with the exception of patients receiving an ineffective treatment for whom the immediate switch to an SSRI or SNRI antidepressant was considered to be the best treatment option. Patients who changed or discontinued medication after entry remained in the study, unless lost to follow-up or consent was withdrawn.

Study therapy

Patients were prescribed any commercially available SSRI or SNRI in accordance with each country’s approved labels and at the discretion of the participating psychiatrist. Treatment decisions were made solely at the discretion of the treating psychiatrist, and were independent of study participation. Patients were not required to continue taking the medication initiated at baseline. Changes in medication and dosing as well as use of concomitant medications and nonpharmacological therapies for the treatment of depression were possible at any time as determined by the treating psychiatrist.

This analysis included only those patients who initiated either duloxetine (duloxetine cohort) or an SSRI (SSRI cohort), both as monotherapy at baseline.

Data collection and outcome assessment

Data collection for the study occurred during visits within the normal course of care. The routine outpatient visit at which patients were enrolled served as the time for baseline data collection. Subsequent data collection was targeted at week 8, week 16, and week 24 following the baseline visit. Patient demographics and clinical history were recorded at the baseline assessment.

Patient perception of QoL was assessed at each visit using the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D), a patient self-rated, generic, QoL measure. This instrument has five items (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), each of which is scored on a scale from 1 (no problems) to 3 (extreme problems). Given that there are no single representative EQ-5D tariffs or country-specific tariffs for all countries included in this analysis, the commonly used UK population tariff was applied to the EQ-5D data to calculate the utility score.34 The EQ-5D questionnaire also includes a visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) on which patients were asked to rate their current overall health that day on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state), thus providing an overall “health state” score. This study focuses on the levels of QoL assessed by the EQ-5D utility score as they are more comprehensive, and complements these with additional results from the EQ-VAS.

Clinical severity of depression was also assessed by the treating psychiatrists using the CGI-S scale31 and self-rated by patients using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR16).35 In addition, depression-related pain severity was measured using the pain-related items of Somatic Symptom Inventory (SSI), which included abdominal pain, lower back pain, joint pain, neck pain, pain in the heart or chest, headaches, and muscular soreness.36 PPS status was also assessed as painful physical symptom negative (PPS−) or positive (PPS+); PPS+ was defined as a mean score of ≥2 for the seven pain-related items of the SSI.

Statistical analysis

This study included a total of 1,332 patients who 1) initiated either duloxetine or an SSRI as monotherapy at baseline for the treatment of MDD, and 2) who did not have missing data on the QIDS-SR16 score at baseline with at least one assessable QIDS-SR16 score during follow-up (n=556 in the duloxetine group and n=776 in the SSRI group). This study analyzed the patient observations up to the point where their initial medications were discontinued. Of the 1,332 patients, 78.7% (n=1,048) were available at 24 weeks (n=443 [79.7%] in the duloxetine group and n=605 [78.0%] in the SSRI group).

Baseline patient characteristics as well as outcomes at each visit by treatment were described and compared using the chi-square test (for categorical variables) and Mann–Whitney test (for continuous variables).

The mean levels (raw values) of QoL at each visit by treatment in the overall sample as well as in the subgroup of PPS+ and PPS− patients, respectively, were also described and compared using the Mann–Whitney test. The effect sizes were also calculated using Cohen’s d (ie, the difference in mean values divided by a standard deviation [SD])37 for the differences in the levels of QoL between the two treatment cohorts at each visit.

Adjusted mixed effects modeling with repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to compare the levels of QoL (EQ-VAS and EQ-5D) during follow-up between the two treatment cohorts. The unstructured covariance pattern was used to take into account within-patient correlation. These models were adjusted for age, sex, region, SSI-pain score at baseline, the baseline value of the outcome modeled, and visit number. In addition, the following variables were included for further adjustment if they appeared to be significant (P<0.1) in simple regressions: independent living (living in his/her own house), living with a spouse/partner, employment level, had MDD episodes in the 24 months prior to baseline, MDD hospitalizations in the 24 months prior to baseline, number of significant preexisting comorbidities, CGI-S and QIDS-SR16 scores at baseline, and the interaction term between time (visit number) and treatment.

These analyses were repeated for subgroups of PPS+ and PPS− patients, respectively, to examine whether the comparative effectiveness of duloxetine versus an SSRI differ between PPS+ and PPS− patients. Similarly, these analyses were also repeated for subgroups of patients treated with duloxetine or an SSRI, respectively, to examine whether an association between baseline pain severity and QoL during follow-up varies with the type of treatment. Treatment-related variables (ie, treatment and its interaction with time) were excluded in the latter subgroup analyses by treatment cohorts. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics at study entry

Of the 1,332 patients included in this analysis, 556 patients (41.7%) initiated duloxetine, and 776 patients (58.3%) initiated an SSRI antidepressant at baseline. The most common SSRIs prescribed at baseline were paroxetine (24.5%), escitalopram (23.7%), sertraline (21.1%), and fluoxetine (19.7%). The median daily doses of these medications at baseline were 20.0 mg/day for paroxetine, 10.0 mg/day for escitalopram, 50.0 mg/day for sertraline, 20.0 mg/day for fluoxetine, and 60.0 mg/day for duloxetine.

Overall, the mean (SD) age of these patients was 38.0 (10.5) years and 56.5% were female. More than one-third of the patients were from Mexico (n=562, 42.2%), followed by East Asia (n=455, 34.2%), the Middle East (n=275, 20.7%), and other countries (ie, Israel and Austria; n=40, 3.0%). In addition, more than half of the patients (n=685, 51.5%) were PPS+ at baseline (58.5% in the duloxetine cohort and 46.5% in the SSRI cohort, P<0.001).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline patient characteristics by treatment cohort. Although the mean age of the patients was similar between the two cohorts, the SSRI cohort had a higher proportion of females, patients from Mexico, patients living in their own apartment or house, and patients having lower education attainment, compared to the duloxetine cohort. Nevertheless, disease severity (CGI-S and QIDS-SR16) was similar between the two cohorts, whereas the mean SSI-pain score at baseline was higher in the duloxetine cohort than in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by treatment cohorts

| Baseline characteristic | Duloxetine (n=556) | SSRI (n=776) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 38.2 (10.2) | 37.9 (10.7) | 0.539 |

| Female, % | 51.8 | 59.8 | 0.004 |

| Region, % | <0.001 | ||

| Mexico | 29.1 | 51.5 | |

| East Asia | 41.4 | 29.0 | |

| The Middle East | 27.3 | 15.9 | |

| Others | 2.2 | 3.6 | |

| Age at first symptoms of MDD, mean (SD), years | 34.3 (10.6) | 33.3 (11.6) | 0.078 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.6 (4.4) | 24.8 (4.3) | 0.277 |

| Living with a spouse/partner, % | 69.9 | 69.7 | 0.948 |

| Independent living (living in his/her own apartment or house), % | 12.4 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Educational attainment, % | 0.020 | ||

| ≤ Primary school | 6.3 | 9.7 | |

| Secondary school/occupational program | 42.3 | 45.2 | |

| ≥ University | 51.4 | 45.1 | |

| Employment status, % | 0.057 | ||

| Full time | 57.0 | 54.5 | |

| Economically inactive | 22.8 | 28.4 | |

| Unemployed/part-time | 20.1 | 17.1 | |

| CGI-S, mean (SD) | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.7) | 0.292 |

| QIDS-SR16, mean (SD) | 14.2 (4.6) | 14.5 (5.0) | 0.356 |

| SSI-pain, mean (SD) | 15.2 (5.1) | 13.8 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Had MDD episodes in the past 24 months, % | 66.2 | 65.3 | 0.747 |

| Number of comorbidities, % | 0.177 | ||

| 0 | 77.0 | 72.5 | |

| 1 | 17.5 | 21.2 | |

| 2+ | 5.4 | 6.2 | |

| Any treatments/therapies for depression in the past 24 months, % | 42.6 | 44.2 | 0.568 |

| Painful physical symptoms, % | 58.5 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity; MDD, major depressive disorder; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report; SD, standard deviation; SSI-pain, somatic symptom inventory; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Improvement in QoL by treatment cohort

Table 2 demonstrates the levels of QoL (raw means), as measured by EQ-5D and additional EQ-VAS, at baseline and at 24 weeks by treatment cohort. There were no statistically significant differences in the levels of QoL at baseline between the two treatment cohorts. The mean EQ-5D score at baseline was 0.46 (SD =0.32) in the duloxetine cohort and 0.47 (SD =0.33) in the SSRI cohort (P=0.066). Similarly, the mean EQ-VAS score at baseline was 43.4 (SD =24.4) in the duloxetine cohort and 43.0 (SD =26.9) in the SSRI cohort (P=0.960). The mean levels of QoL at baseline were also similar between the two cohorts in each subgroup of PPS+ and PPS− patients, respectively, although the level of QoL was generally higher in PPS− patients.

Table 2.

Mean levels (raw values) of QoL at baseline and at 24 weeks by treatment cohorts with and without PPS at baseline

| Outcome | Total

|

PPS+

|

PPS−

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | |

| EQ-5D | |||||||||

| At baseline | 0.46 (0.32) | 0.47 (0.33) | −0.03 | 0.37 (0.33) | 0.40 (0.34) | −0.09 | 0.58 (0.26) | 0.54 (0.31) | 0.14 |

| At week 24 | 0.95 (0.11)b | 0.90 (0.16) | 0.35 | 0.95 (0.10)b | 0.86 (0.19) | 0.59 | 0.95 (0.12)b | 0.92 (0.12) | 0.25 |

| EQ-VAS | |||||||||

| At baseline | 43.39 (24.36) | 42.99 (26.94) | 0.02 | 40.77 (24.23) | 39.48 (27.25) | 0.05 | 47.07 (24.11) | 46.02 (26.36) | 0.04 |

| At week 24 | 75.64 (34.02)b | 69.02 (32.79) | 0.20 | 74.88 (34.94)b | 66.88 (33.28) | 0.23 | 76.75 (32.69)b | 70.62 (32.38) | 0.19 |

Notes:

These show effect sizes of QoL differences between treatment cohorts.

P<0.05 for all comparisons of outcomes between the duloxetine cohort and the SSRI cohort in the overall sample, PPS+ patients, and PPS- patients, respectively.

Abbreviations: EQ-VAS, EuroQoL-Visual Analog Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 Dimensions; PPS, painful physical symptoms; QoL, quality of life; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

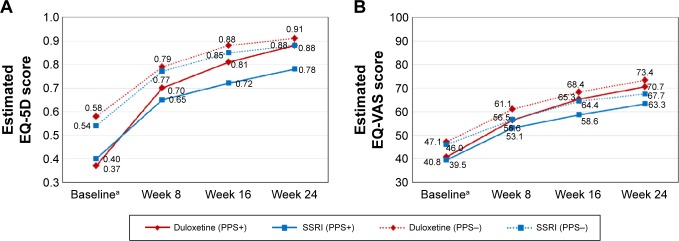

Despite similar levels of QoL at baseline between the two treatment cohorts, duloxetine-treated patients achieved greater levels of QoL throughout the follow-up period, compared to SSRI-treated patients. The mean EQ-5D score at 24 weeks was 0.95 (SD =0.11) in the duloxetine cohort and 0.90 (SD =0.16) in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001). A similar pattern was also observed with the EQ-VAS results (75.6 [SD =34.0] in the duloxetine cohort versus 69.0 [SD =32.8] in the SSRI cohort, P<0.001). In addition, duloxetine-treated patients achieved greater levels of QoL than SSRI-treated patients in each subgroup of PPS+ and PPS− patients, respectively. Notably, the difference in the levels of QoL between the two treatment cohorts at 24 weeks appeared to be greater in PPS+ patients than in PPS− patients. The effect size of this treatment difference in terms of EQ-5D scores was 0.59 in PPS+ patients but 0.25 in PPS− patients. Although, a similar pattern was observed with EQ-VAS scores, the differences in the effect sizes between PPS+ (0.23) and PPS− patients (0.19) were rather modest.

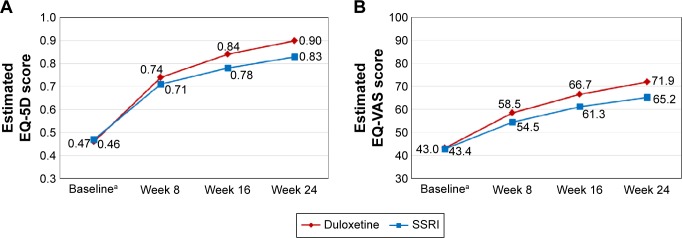

The superiority of duloxetine over SSRIs in terms of QoL improvement was maintained even when the baseline differences between the two treatment cohorts were adjusted for (Figure 1). Given the interaction term between time and treatment included in the MMRM models (Tables 3 and 4), the interpretation of the coefficients of treatment, time and their interaction was not straightforward. Therefore, the (adjusted) mean levels of QoL (ie, least squares means) at each postbaseline visit by treatment cohorts were further estimated and presented in Figure 1. The MMRM results also showed that duloxetine-treated patients achieved higher levels of QoL (both EQ-5D and EQ-VAS), compared to SSRI-treated patients, throughout follow-up (P<0.01 for all treatment comparisons at each postbaseline visit). At 24 weeks, the estimated mean EQ-5D score was 0.90 (standard error [SE] =0.01) in the duloxetine cohort, which was higher than that of 0.83 (SE =0.01) in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001). Similarly, the estimated mean EQ-VAS score was 71.9 (SE =1.8) in the duloxetine cohort and 65.2 (SE =1.7) in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001). Consistent with the descriptive results, the difference in the levels of QoL at 24 weeks between the two treatment cohorts was greater in the subgroup of PPS+ patients than in that of PPS- patients (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The estimated mean levels of QoL during follow-up by treatment cohorts.

Notes: (A) EQ-5D scores by treatment cohorts. (B) EQ-VAS scores by treatment cohorts. P<0.05 for all comparisons between the duloxetine cohort and the SSRI cohort at each postbaseline visit. aThe baseline scores are raw mean values.

Abbreviations: SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; QoL, quality of life; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 Dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQoL-Visual Analog Scale.

Table 3.

The results of MMRM analyses: factors associated with EQ-5D scores during follow-up

| Parameter | Parameter estimate | Standard error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.850 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.095 |

| Female (versus male) | −0.022 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| Region (versus East Asia) | |||

| Mexico | 0.025 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| The Middle East | −0.028 | 0.012 | 0.019 |

| Others | −0.038 | 0.026 | 0.140 |

| Employment (versus full time) | |||

| Economically inactive | −0.019 | 0.009 | 0.048 |

| Unemployed/part-time | −0.013 | 0.011 | 0.236 |

| Not living in his/her own house | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.029 |

| EQ-5D index at baseline | 0.087 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| QIDS-SR16 score at baseline | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.107 |

| SSI-pain score at baseline | −0.004 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities (versus none) | |||

| 1 | −0.034 | 0.010 | 0.001 |

| 2+ | −0.113 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| Had MDD episodes in the 24 months prior to baseline | −0.021 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Duloxetine (versus SSRI) | 0.034 | 0.011 | 0.002 |

| Weeks (versus week 8) | |||

| Week 16 | 0.072 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Week 24 | 0.117 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| Weeks × treat | |||

| Duloxetine at week 16 | 0.027 | 0.011 | 0.012 |

| Duloxetine at week 24 | 0.035 | 0.012 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 Dimensions; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; MMRM, mixed effects modeling with repeated measures; MDD, major depressive disorder; SSI-pain, somatic symptom inventory; QoL, quality of life.

Table 4.

The results of MMRM analyses: factors associated with EQ-VAS scores during follow-up

| Parameter | Parameter estimate | Standard error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 18.371 | 5.498 | 0.001 |

| Age | −0.164 | 0.061 | 0.007 |

| Female (versus male) | −1.022 | 1.302 | 0.433 |

| Region (versus East Asia) | |||

| Mexico | −5.353 | 1.539 | 0.001 |

| The Middle East | −16.048 | 1.813 | <0.001 |

| Others | −8.566 | 4.161 | 0.040 |

| CGI-S score at baseline | 4.190 | 0.954 | <0.001 |

| EQ-VAS score at baseline | 0.733 | 0.025 | <0.001 |

| SSI-pain score at baseline | 0.237 | 0.129 | 0.068 |

| Comorbidities (versus none) | |||

| 1 | −4.181 | 1.680 | 0.013 |

| 2+ | −5.546 | 2.981 | 0.063 |

| Had MDD episodes in the 24 months prior to baseline | −1.071 | 1.328 | 0.420 |

| Duloxetine (versus SSRI) | 3.953 | 1.322 | 0.003 |

| Weeks (versus week 8) | |||

| Week 16 | 6.741 | 0.586 | <0.001 |

| Week 24 | 10.656 | 0.719 | <0.001 |

| Weeks × treat | |||

| Duloxetine at week 16 | 1.456 | 0.901 | 0.106 |

| Duloxetine at week 24 | 2.793 | 1.106 | 0.012 |

Abbreviations: EQ-VAS, EuroQoL-Visual Analog Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; MMRM, mixed effects modeling with repeated measures; MDD, major depressive disorder; SSI-pain, somatic symptom inventory; QoL, quality of life.

Figure 2.

The estimated mean levels of QoL during follow-up by treatment cohorts in patients with and without PPS at baseline.

Notes: (A) EQ-5D scores by treatment cohorts. (B) EQ-VAS scores by treatment cohorts. P<0.05 for all comparisons between the duloxetine cohort and the SSRI cohort at 24 weeks in both PPS+ and PPS− patients, respectively. aThe baseline scores are raw mean values.

Abbreviations: PPS, painful physical symptoms; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; QoL, quality of life; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5 Dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQoL-Visual Analog Scale.

Notably, the SSI-pain score at baseline was significantly associated with poorer QoL during follow-up, as measured by EQ-5D (P<0.001; P=0.068 for the association with EQ-VAS). This analysis was repeated in each subgroup of patients treated with duloxetine or an SSRI, respectively. While this association between pain severity and QoL, as measured by EQ-5D, was also observed in SSRI-treated patients (P<0.001), this relationship was not retained in duloxetine-treated patients (P=0.479) (data not shown).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of data from a 6-month, prospective, observational study conducted mostly in East Asia, the Middle East, and Mexico shows that although both duloxetine and SSRIs improve patient’s QoL in the treatment of MDD, the effect of duloxetine is likely greater than that of SSRIs in this population. These findings are consistent with other treatment outcomes.38,39 Specifically, the mean EQ-5D score increased from 0.46 at study entry to 0.90 (estimated mean) at 24 weeks in duloxetine-treated patients and from 0.47 at study entry to 0.83 (estimated mean) at 24 weeks in SSRI-treated patients. The difference in the QoL at 24 weeks between the two treatment cohorts appeared to be more pronounced in patients with PPSs at baseline than in patients without such symptoms at baseline. Nevertheless, overall, both treatment groups achieved a level of QoL very close to that of general population, which ranges from 0.833 in Zimbabwe (Harare district) to 0.958 in South Korea, among 15 countries/regions providing population data with country-specific tariffs.40 In addition, our results confirm a negative association between the severity of pain at baseline and levels of QoL during follow-up, as measured by EQ-5D. Notably, this relationship was not observed in the subgroup of patients treated with duloxetine, but clearly observed in those treated with SSRIs.

The World Health Organization defines health-related QoL as an:

Individual’s perception of their position in life […] It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship to salient features of their environment.41

QoL is increasingly recognized as an important measure of health in medical and psychiatric patients.7,42 Not surprisingly, the baseline EQ-5D scores indicate that, on average, our study patients had moderately impaired QoL at baseline, according to a recent review on utility values of depressed patients.43 Our study also suggests that treatment with antidepressants can improve the level of QoL, helping patients return to a “normal level” of QoL. However, despite increasing awareness and recognition of QoL as an important treatment outcome, the use of QoL as an outcome measure has been very limited in clinical trials that assess the comparative effectiveness of different treatments for MDD.

Instead, several studies have examined the comparative effectiveness of SNRIs including duloxetine and SSRIs in terms of symptom improvement, but the superiority of SNRIs over SSRIs has not been well established in the literature. Some studies have suggested that dual acting monoamine inhibitors such as the SNRIs may be more efficacious than those that work by inhibiting only one monoamine,13,14 while others have reported no significant or clinically meaningful differences between the two classes of medications.15,44 A recent systematic review also reported no difference in efficacy between duloxetine and SSRIs.16

Nevertheless, emerging empirical evidence suggests that “dual-action drugs” like the SNRIs including duloxetine may have additional advantages for patients with concurrent pain and depression.13,14,17 Notably, approximately 51% of patients in our study suffered from PPSs at baseline (59% in the duloxetine cohort and 47% in the SSRI cohort). More importantly, the findings of both descriptive and regression analyses confirmed this additional advantage of duloxetine over SSRIs in patients with PPSs at baseline. The effect size of the difference in EQ-5D scores at 24 weeks between the two treatment cohorts was 0.59 (“medium” effect difference) in patients with PPSs at baseline but 0.25 (“small” effect difference) in patients without PPSs at baseline.37 A similar pattern was also observed even after baseline patient characteristics were adjusted for in the multiple regressions.

In this light, the subgroup analyses by treatment cohorts also revealed some interesting findings. Our study found a negative association between baseline pain severity and QoL during follow-up. However, patients taking duloxetine achieved the same level of QoL independently of pain severity at baseline, whereas this was not the case for the subgroup of patients taking SSRIs. That is, patients taking SSRIs who had a higher level of pain severity at baseline did not achieve the same level of QoL as those taking SSRIs who had a lower level of pain severity at baseline, confirming the negative impact of pain on improvement of QoL in this cohort (but not in the duloxetine cohort). Taken together, our findings reconfirm the importance of controlling pain symptoms in the treatment of depression and the potential advantages of duloxetine over SSRIs, at least for patients with concurrent pain and depression.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the following study limitations. First, given the observational design of this study, our findings do not imply causal relationships. Although we employed statistical modeling techniques to limit potential sources of bias between treatment groups at study entry, the statistical techniques used cannot completely eliminate the impact of imbalances between treatment groups. Secondly, as the primary objective of this observational study was to assess the frequency of TESD in the treatment of MDD, the study included only those patients who were sexually active without sexual dysfunction at baseline. Sexual dysfunction has been reported to be two to three times more prevalent in patients with depression compared to the general population,45,46 and thus our findings may not be immediately generalizable to patients with MDD as a whole. Further research is warranted to examine whether these findings can be replicated in MDD patients without such inclusion/exclusion criteria. Finally, given that there are no single representative EQ-5D tariffs or country-specific tariffs for all countries included in our analysis, we applied the commonly used UK tariff to the EQ-5D data to calculate utility scores.34 While there is evidence that different populations value health states differently (including racial/ethnic differences),47 the EQ-5D has been shown to be useful for assessing QoL in patients with MDD.48

Conclusion

Patients treated with duloxetine achieved higher levels of health-related QoL compared to those treated with SSRIs for the management of MDD in actual clinical practice settings mostly in East Asia, the Middle East, and Mexico. The superiority of duloxetine over SSRIs on QoL outcomes appeared to be more pronounced in patients with PPSs than in patients without such symptoms at baseline. In addition, we also found that patients taking duloxetine, unlike patients taking SSRIs, achieved the same level of QoL independently of their pain severity at baseline. This suggests that the negative impact of pain on QoL may be mitigated somewhat by treatment with duloxetine, which may in turn help explain the higher level of QoL found for duloxetine-treated patients. However, given that our study included only those patients who were sexually active without sexual dysfunction at baseline, these findings may not be immediately generalizable to patients with MDD as a whole and should therefore be validated with MDD patients without such inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Jihyung Hong is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company. Diego Novick, William Montgomery, Héctor Dueñas, and Xiaomei Peng are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. Maria Victoria Moneta conducted the statistical analysis under a contract between Fundació Sant Joan de Déu and Eli Lilly and Company. Josep Maria Haro acted as a consultant, received grants, or acted as a speaker in activities sponsored by the following companies: Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, and Lundbeck. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.WHO Depression. [Accessed August 13, 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- 2.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, Endicott J. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1171–1178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angermeyer MC, Holzinger A, Matschinger H, Stengler-Wenzke K. Depression and quality of life: results of a follow-up study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(3):189–199. doi: 10.1177/002076402128783235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschfeld RM, Dunner DL, Keitner G, et al. Does psychosocial functioning improve independent of depressive symptoms? A comparison of nefazodone, psychotherapy, and their combination. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishak WW, Christensen S, Sayer G, et al. Sexual satisfaction and quality of life in major depressive disorder before and after treatment with citalopram in the STAR*D study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(3):256–261. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IsHak WW, Mirocha J, James D, et al. Quality of life in major depressive disorder before/after multiple steps of treatment and one-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/acps.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IsHak WW, Greenberg JM, Balayan K, et al. Quality of life: the ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):229–239. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.614099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilcha-Mano S, Dinger U, McCarthy KS, Barrett MS, Barber JP. Changes in well-being and quality of life in a randomized trial comparing dynamic psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.APA . Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(4):343–396. doi: 10.1177/0269881107088441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S26–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:234–241. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, Nelson JC, Shelton RC. Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(6):415–426. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cipriani A, Koesters M, Furukawa TA, et al. Duloxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006533. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006533.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thase ME, Pritchett YL, Ossanna MJ, Swindle RW, Xu J, Detke MJ. Efficacy of duloxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: comparisons as assessed by remission rates in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):672–676. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815a4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bymaster FP, Lee TC, Knadler MP, Detke MJ, Iyengar S. The dual transporter inhibitor duloxetine: a review of its preclinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetic profile, and clinical results in depression. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(12):1475–1493. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MJ, Sheehan D, Gaynor PJ, et al. Relationship between major depressive disorder and associated painful physical symptoms: analysis of data from two pooled placebo-controlled, randomized studies of duloxetine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28(6):330–338. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328364381b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brecht S, Courtecuisse C, Debieuvre C, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1707–1716. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fava M, Mallinckrodt CH, Detke MJ, Watkin JG, Wohlreich MM. The effect of duloxetine on painful physical symptoms in depressed patients: do improvements in these symptoms result in higher remission rates? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):521–530. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moultry AM, Poon IO. The use of antidepressants for chronic pain. US Pharm. 2009;34(5):26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Pain, pain, go away: antidepressants and pain management. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008;5(12):16–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung AC, Staiger T, Sullivan M. The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the management of chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):384–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duenas H, Brnabic AJM, Lee A, et al. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction with SSRIs and duloxetine: effectiveness and functional outcomes over a 6-month observational period. Int J Psychiatry in Clin Pract. 2011;15(4):242–254. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.590209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duenas H, Lee A, Brnabic AJM, et al. Frequency of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and treatment effectiveness during SSRI or duloxetine therapy: 8-week data from a 6-month observational study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(2):80–90. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.572169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (Revised) Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/009262300278623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berlim MT, Turecki G. What is the meaning of treatment resistant/refractory major depression (TRD)? A systematic review of current randomized trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(11):696–707. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks R, Rabin R, de Charro F. The Measurement and Valuation of Health Status using EQ-5D: A European Perspective. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong J, Novick D, Montgomery W, et al. Real-world outcomes in patients with depression treated with duloxetine or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in East Asia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2015 Mar 24; doi: 10.1111/appy.12178. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novick D, Hong J, Montgomery W, Duenas H, Gado M, Haro JM. Predictors of remission in the treatment of major depressive disorder: real-world evidence from a 6-month prospective observational study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:197–205. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S75498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szende A, Janssen B, Cabase J, editors. Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective Based on EQ-5D. New York, NY: Springer Open; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organisation . WHOQOL. Measuring Quality of Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1997. [Accessed August 24, 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langlieb AM, Guico-Pabia CJ. Beyond symptomatic improvement: assessing real-world outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(2) doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00826blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohiuddin S, Payne K. Utility values for adults with unipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(5):666–685. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14524990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision) Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4 Suppl):1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Angst J. Sexual problems in healthy and depressed persons. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(Suppl 6):S1–S4. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199807006-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonierbale M, Lancon C, Tignol J. The ELIXIR study: evaluation of sexual dysfunction in 4557 depressed patients in France. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19(2):114–124. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu AZ, Kattan MW. Racial and ethnic differences in preference-based health status measure. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(12):2439–2448. doi: 10.1185/030079906X148391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sapin C, Fantino B, Nowicki ML, Kind P. Usefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]