Abstract

Recent advances with immunotherapy agents for the treatment of cancer has provided remarkable, and in some cases, curative results. Our laboratory has identified CD47 as an important “don’t eat me” signal expressed on malignant cells. Blockade of the CD47:SIRP-α axis between tumor cells and innate immune cells (monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells) increases tumor cell phagocytosis in both solid tumors (including, but not limited to bladder, breast, colon, lung, pancreatic) and hematological malignancies. These phagocytic innate cells are also professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), providing a link from innate to adaptive anti-tumor immunity. Preliminary studies have demonstrated that APCs present antigens from phagocytosed tumor cells, causing T cell activation. Therefore, agents that block CD47:SIRP-α engagement are attractive therapeutic targets as a monotherapy or in combination with additional immune modulating agents for activating anti-tumor T cells in vivo.

Background

Tumors are able to evade immune recognition and removal through multiple processes including creating an immunosuppressive environment, or direct tumor:immune cell interactions (1–4). One mechanism to avoid removal by innate immune cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) is to upregulate “don’t eat me” signals preventing phagocytosis (5). In addition to preventing programed cell removal (PrCR) by reducing total phagocytosis, antigen presentation from innate to adaptive immune cells is limited thereby restricting the cross-presentation to the adaptive immune cells (1, 4). As a result, immunotherapies that increase tumor cell recognition by innate immune cells should also act as stimulation to the adaptive immune response in vivo.

CD47—a “don’t eat me” signal on cells

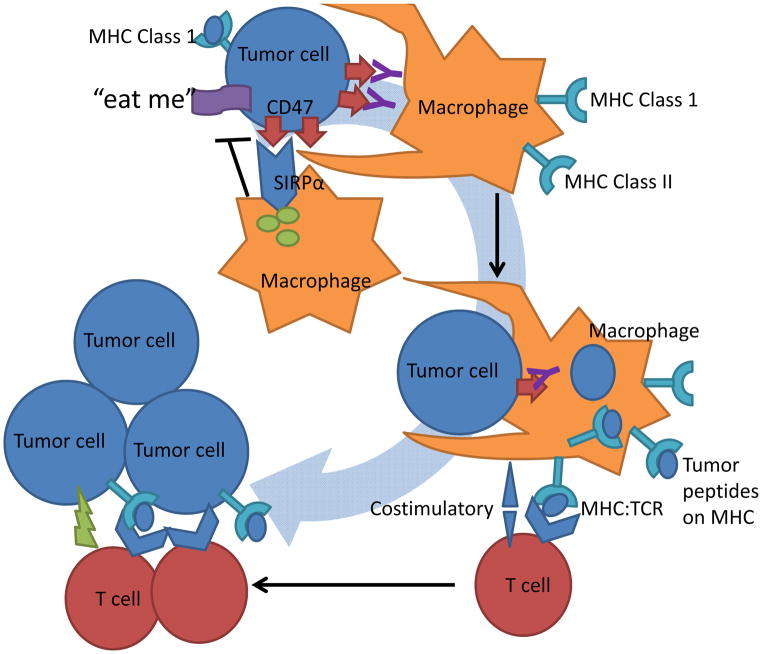

CD47, a transmembrane protein found ubiquitously expressed on normal cells to mark “self” has increased expression in circulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), red blood cells (RBCs), and a high proportion of malignant cells (4, 5). Although CD47 has multiple functions in normal cell physiology, in cancer it acts primarily as a dominant “don’t eat me” signal (Fig. 1) (4, 5). On tumor cells pro-phagocytic signals may be present, but if the tumor cells are expressing CD47 it can bind with signal regulatory protein-α (SIRP-α) on phagocytic immune cells preventing engulfment (Fig. 1) (4, 6–8). CD47:SIRP-α engagement results in activation of SIRP-α by which phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition (ITIM) motifs leading to the recruitment of Src homology phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) and SHP-2 phosphatases preventing myosin-IIA accumulation at the phagocytic synapse preventing phagocytosis (Fig. 1) (9). This inhibitory mechanism of CD47 expression is seen in a broad range of malignancies and is therefore an attractive therapeutic target for all tumors expressing CD47 (5, 6, 10–22). In pre-clinical models, disruption of CD47:SIRP-α axis results in enhanced phagocytosis, tumor reduction, and recently has been demonstrated as a means to cross present tumor antigens to T cells (Fig. 1) (11, 15).

Figure 1.

Tumor cells display MHC class I, surface markers of ‘self’, anti-phagocytic-‘don’t eat me’ and phagocytic-‘eat me’ signals. Engagement of tumor cells CD47 (‘don’t eat me’ signal) with macrophages SIRP-α causes activation and phosphorylation of SIRP-α ITIM motifs and the recruitment of SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases preventing myosin-IIA accumulation at the phagocytic synapse inhibiting tumor cell phagocytosis. By blocking the CD47:SIRP-α engagement with antibodies (or alternate strategies) an increase in tumor cell phagocytosis by APCs is observed. The engulfed tumor cells are then processed and tumor associated antigens are presented by these APCs on their MHC. Naïve tumor reactive T cells can then engage with MHC on APCs presenting tumor neo-antigens with additional co-stimulatory molecules. These tumor specific T cells are then activated, expand, and are able to cause antigen specific tumor cell cytotoxicity on remaining malignant cells.

To date, several strategies to block CD47:SIRP-α interaction have been developed including antibodies or antibody fragments against CD47 or SIRP-α (6, 19, 23), small peptides that bind CD47 or SIRP-α (12, 16), or systemic knockdown of CD47 expression (6, 15, 21). One advantage of antibodies that target CD47 is the increase in antibody dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) which occurs when innate immune cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) Fcγ receptors (FcγR) bind to the Fc portion of the anti-CD47 antibody (6, 24, 25). To further increase antibody dependent cellular phagocytosis anti-CD47 combination with additional tumor targeting antibodies has been tested pre-clinically and shown strong synergy in reducing total tumor burden in mice (6, 12, 16, 18). The majority of these studies have been performed in NSG mice, which contain innate immune cells, but lack T, B and natural killer (NK) cells. NK cells are the dominant cells responsible for antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), as a result the effects of NK cells after anti-CD47 treatment are not well studied (6, 26). Consequently, only a limited number of studies have investigated how CD47:SIRP-α blockade primes the adaptive immune response in immunocompetent systems.

Activating adaptive anti-tumor immunity in vivo

Activation of the adaptive immune system, T and B cells, is antigen-specific and allows for a targeted immune response. T cells specificity comes from their T cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes a distinct peptide (antigen) when displayed in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (27). T cells are subdivided into two major classes; CD8-cytotoxic T cells (TC or CTLs) or CD4-T helper (TH). Cytotoxic T cells can directly kill target cells when their TCR recognizes an 8–10 amino acid sequence that is displayed on MHC Class I (27). In general, MHC Class I is expressed on all cells, including tumor cells, and present intracellular or endogenous peptides. Tumor reactive Cytotoxic T cells recognize neo-antigens (peptides present within the cancer cell from mutations, that are not present on normal cells) allowing selective cytotoxicity of tumor cells (Fig. 1) (27). Naïve T cells need an initial activation by APCs that have phagocytosed tumor cells and present these tumor neo-antigens (1, 3, 27). TCR/MHC recognition as well as engagement of additional co-stimulatory molecules occurs between the T cell/APC causing rapid expansion, cytokine production, and development of a memory T cell subset (Fig. 1) (1, 3, 27). Without initial activation by APCs and costimulation, T cells can become anergic rather than activated dampening the total anti-tumor T cell response (1–3, 27–29). In cancer, activation of tumor reactive T cells can provide long-term tumor free survival by a continuous elimination of all malignant cells (1, 3, 27, 30). The memory T cell subset allows for a continued surveillance and identification of any cell expressing the tumor antigen at later times. Similar to lasting anti-viral responses, these tumor reactive T cells can last for decades providing the long-term tumor free survival seen in some patients treated with immunotherapies (30). Therefore, a strong innate immune response is critical for mounting the maximum anti-tumor response (31). By increasing tumor cell phagocytosis with blockade of CD47:SIRP-α, an enhancement in antigen presentation and T cell priming should occur in vivo.

Pre-clinical evaluation for activating the adaptive immune response following CD47 blockade

In vitro, we have demonstrated that macrophages and dendritic cells increased their phagocytosis of tumor cells expressing the Ovalbumin antigen (Ova) when cells were treated with anti-CD47 (11). In this study and others by our lab, macrophages were the dominant phagocytic cell after anti-CD47 treatment (4, 11, 17). After phagocytosis, these macrophages secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines, and upregulated the co-stimulatory molecule CD86. These macrophages were then co-cultured with Ova specific T cells (OT-I CD8, OT-II CD4). OT-I cells were activated and primed by these macrophages, while interestingly, OT-II cells were not. OT-I cells could also be activated in vivo by adoptive transfer of macrophages (that had phagocytosed Ova expressing tumor cells with the aid of anti-CD47 antibodies) providing them protection from the establishment of transplanted Ova tumors (11). The same Ova expressing tumor cells co-incubated with the same types of macrophages in the absence of anti-CD47 blocking antibodies, but in the presence of anti-CD47 antibodies that do not interfere with CD47: SIRP-α interactions, do not cross-present Ova peptides to OT 1 cells in vitro or in vivo. These results demonstrate that anti-CD47 treatment induces macrophages to be efficient APCs to stimulate T cells in vitro and in vivo. In a separate study, the knockdown of CD47 has also been shown to synergize with radiotherapy by increasing the total quantity of tumor infiltrated CD8+ cells (15). In mice lacking T cells, this synergy was lost demonstrating that radiotherapy is an adjuvant to increase the adaptive immune response after CD47 blockade.

These studies provide strong evidence that CD47 blockade and tumor cell phagocytosis can efficiently prime CD8 T cells. It is still unclear however how CD4 cells, including Treg cells, are affected by CD47 blockade. Additionally, most adaptive immune studies have been performed with a defined tumor antigen. Will CD47 blockade provide sufficient T cell priming in an un-defined tumor antigen or in those tumors with moderate to low mutation loads? Lastly, CD47 blockade synergizes with irradiation and combination antibody therapies in pre-clinical models, will these translate into clinical efficacy as well?

Clinical–Translational Advances

CD47 blocking agents in clinical development

Translation of CD47 blocking therapies into clinical use is new, with no FDA approved drugs. Therefore, little is known about potential side effects, resistance, or what combination therapies will be most efficacious. To date, several academic and industry labs have CD47 blocking agents under development with open enrollment or planned clinical trials in targeting both hematological and solid tumors. In the USA, two phase 1 dose escalation trials are currently underway with anti-CD47 antibodies as a monotherapy for the treatment of advanced solid tumors and hematological cancers (Trial registration IDs: NCT02216409, NCT02367196). No outcome data has been reported yet, but those currently in progress will be used to determine the toxicity and maximum tolerated dose with antitumor efficacy as a secondary measurement for this phase. Additional agents being developed within pharmaceutical companies are high affinity SIRP-α mimics including a fusion protein “SIRPαFc” that combines a portion of SIRP-α fused to the Fc region of an antibody to retain ADCP.

Potential adverse events or resistance mechanisms in CD47 blockade

In clinical applications, anti-CD47 is not predicted to have adverse drug interactions or side effects. Anticipated off-target effects of CD47:SIRP-α blockade include potential allergic reactions to humanized antibodies, or removal of non-malignant CD47 expressing cells (4). In particular, CD47 expression on red blood cells is a mechanism that prevents programed cell removal (32). Initial dosing of anti-CD47 is therefore expected to cause a significant reduction in total red blood cell count. To lessen this effect, a priming dose of anti-CD47 can be given to remove “aged” red blood cells and to stimulate erythropoiesis (J. Liu et al.; manuscript in preparation). Newly developed red blood cells should not be significantly affected during the remaining anti-CD47 therapy. If red blood cell counts remain low after priming and during therapy, erythropoietin or transfusions can also be given to alleviate this.

An additional concern of a new drug is potential resistance including loss of expression, amplification, mutations, or alternative non-CD47 related tumor cell adaptations. To date no common mechanisms have been described pre-clinically. Loss of CD47 by tumor cells is not expected, and if this occurs it will mimic the blocking effect of anti-CD47. Amplification will not cause total resistance but may be one mechanism to dampen efficacy if therapeutic antibody dosing is not at an antigen saturating level. Mutations in CD47 may occur, but these need to prevent antibody binding while retaining the CD47:SIRP-α interaction. Alternatively, the upregulation of additional “don’t eat me” or “immune tolerance” signals can cause resistance (31). These changes may be induced after anti-CD47 therapy, or might be present initially and will be selected for during therapy. Identifying the resistance mechanism to anti-CD47 clinically can provide information on additional future drug targets, or combination therapies to reduce the identified resistance.

Identifying synergistic combination therapies with CD47 blockade

Based on preclinical studies, anti-CD47 (and SIRPαFc) is expected to have efficacy as a monotherapy, with the most promising preclinical data in acute myelogenous leukemia (4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 17, 20–22, 25). Combining CD47 blocking agents with additional immunotherapies is believed to further increase efficacy in a wider range of cancers and provide potential cures. A previous study demonstrated that the combination of anti-CD20 (Rituximab) with anti-CD47 therapy cured NSG mice transplanted with human B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (18). Single agents increased survival, but could not induce a full clearance of the transplanted lymphoma. These antibodies synergized by combining Fc receptor (FcR)-dependent tumor targeting (anti-CD20) and blocking CD47:SIRP-α. In solid tumors, blocking CD47 with a high affinity soluble SIRP-α in combination with anti-Her2 provided a significant decrease in total tumor cell volume of breast cancers within the mouse mammary fat pad (12). The robust effect of combining these antibodies in both solid and blood malignancies should lead to alternative combination therapies mimicking this method for other cancers.

In particular, combination immunotherapies may provide the proper stimulation to both innate and adaptive immune cells to induce total tumor eradication and lasting anti-tumor T cell memory. Immunotherapies are being developed to increase the anti-tumor response by blocking inhibitory signals, agonizing stimulatory signals, systemic cytokines, vaccinations, or adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with expanded tumor infiltrated lymphocytes (TILs) (3, 30). Combining an increase in phagocytosis/tumor cell removal by CD47 blocking agents should synergize with immunotherapies such as anti-CD40, IL-2, anti-CTLA4, anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, or adoptive cell therapy. CD40 is widely expressed on innate immune cells and when targeted with an agonistic antibody it can directly activate APCs increasing MHC expression and costimulatory molecules that then activate an adaptive immune response through antigen cross presentation (33, 34). Anti-CD40 has been efficacious when combined with systemic IL-2 which can non-specifically activate T cells in vivo (35). Combining anti-CD47 with anti-CD40 should increase total APC activation and phagocytosis increasing total tumor cell removal, with each antibody targeting two separate pathways in innate immunity. The upregulation of MHC by CD40 stimulation can help phagocytosed tumor antigens be cross presented to naïve T cells (33).

Alternatively, to target both innate and adaptive immunity, anti-CD47 (or anti-CD47/anti-CD40 combination) can be combined with checkpoint inhibitors (anti-CTLA4, anti-PD-1, and anti-PD-L1). Combination of these agents is predicted to increase antigen cross presentation and anti-tumor T cell development. Checkpoint inhibitors have been highly efficacious as single agents or when used in combination with each other, and are able to increase the T cell response by blocking “negative” feedback inhibition (3). These checkpoint antibodies have also been tested with co-administration of dendritic cell (DC) vaccines or radiotherapy as adjuvants to initiate an immune response (3, 28, 36). The dendritic cell vaccines aim to stimulate and activate naïve T cells by TCR/MHC and costimulatory signaling, while the checkpoint inhibitor blocks T cell exhaustion (29, 37). A problem with checkpoint inhibitor antagonist antibody treatment is that all active or exhausted T cells will be stimulated, both anti-tumor and anti-self autoimmune T cells. Anti-CD47 could be added in addition to these regimens to allow macrophages to activate and prime anti-tumor T cells. This could lead to selective amplification of anti-tumor T cells, and subsequent anti-checkpoint blockade antibodies could conceivably be used at lower doses in order to amplify anti-tumor and not amplify anti-self T cells. Within the tumor, anti-CD47 therapy will increase the phagocytosis and these macrophages and may provide additional stimulation for TILs reducing the previously immunosuppressive tumor microenviroment (1, 3, 15); and both these macrophages and TILs are likely to enter draining lymph nodes to amplify existing and to induce new T cell responses. The removal of tumor cells by phagocytosis is also beneficial to reduce total tumor burden. Tumor cells will be engulfed entirely after anti-CD47 allowing for the presentation of tumor antigens on macrophages to T cells in vivo.

Conclusions

CD47 blocking agents are expected to be well tolerated, efficacious and broadly applicable for cancer therapies. As discussed above, a strong synergy is predicted when combining CD47 blockade with alternate immunotherapies. If clinical studies reflect the current pre-clinical data, the inhibition of CD47:SIRP-α should activate adaptive immunity without directly targeting T cells. Clinical trial and future studies will demonstrate if the proposed therapies with anti-CD47 can truly activate both innate and adaptive immunity to allow for significant tumor reduction, and ideally, cures.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

M.N. McCracken is supported by PHS Grant Number T32 CA09151, awarded by the NCI, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A.C. Cha is supported by a fellowship from the Institute of Biomedical Studies Fellowship at Baylor University and the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research. I.L. Weissman is supported by the NCI and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH through grants R01CA086017, P01CA139490, and R01HL058770; the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine through grants DR1-01485 and DR3-06965; the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research; and the Joseph & Laurie Lacob Gynecologic/Ovarian Cancer Fund.

The authors thank Dr. Jens-Peter Volkmer for his helpful input and critical review.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao MP, Weissman IL, Majeti R. The CD47-SIRPalpha pathway in cancer immune evasion and potential therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, Park CY, Chao MP, Majeti R, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao XW, van Beek EM, Schornagel K, Van der Maaden H, Van Houdt M, Otten MA, et al. CD47-signal regulatory protein-alpha (SIRPalpha) interactions form a barrier for antibody-mediated tumor cell destruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106550108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao MP, Jaiswal S, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, Alizadeh AA, Gentles AJ, Volkmer J, et al. Calreticulin is the dominant pro-phagocytic signal on multiple human cancers and is counterbalanced by CD47. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:63ra94. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng M, Chen JY, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, Volkmer JP, Ho PY, McKenna KM, et al. Macrophages eat cancer cells using their own calreticulin as a guide: roles of TLR and Btk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424907112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai RK, Discher DE. Inhibition of “self” engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:989–1003. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willingham SB, Volkmer JP, Gentles AJ, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Mitra SS, et al. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6662–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng D, Volkmer JP, Willingham SB, Contreras-Trujillo H, Fathman JW, Fernhoff NB, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody-mediated phagocytosis of cancer by macrophages primes an effective antitumor T-cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:11103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305569110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiskopf K, Ring AM, Ho CC, Volkmer JP, Levin AM, Volkmer AK, et al. Engineered SIRPalpha variants as immunotherapeutic adjuvants to anticancer antibodies. Science. 2013;341:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1238856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edris B, Weiskopf K, Volkmer AK, Volkmer JP, Willingham SB, Contreras-Trujillo H, et al. Antibody therapy targeting the CD47 protein is effective in a model of aggressive metastatic leiomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6656–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121629109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim D, Wang J, Willingham SB, Martin R, Wernig G, Weissman IL. Anti-CD47 antibodies promote phagocytosis and inhibit the growth of human myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2012;26:2538–45. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soto-Pantoja DR, Terabe M, Ghosh A, Ridnour LA, DeGraff WG, Wink DA, et al. CD47 in the tumor microenvironment limits cooperation between antitumor T-cell immunity and radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6771–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0037-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho CC, Guo N, Sockolosky JT, Ring AM, Weiskopf K, Ozkan E, et al. ‘Velcro’ engineering of high-affinity CD47 Ectodomain as SIRPalpha antagonists that enhance antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12650–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.648220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Jan M, Weissman-Tsukamoto R, Zhao F, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of CD47 eliminates human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1374–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Tang C, Myklebust JH, Varghese B, Gill S, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. 2010;142:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, Pang WW, Jaiswal S, Gibbs KD, Jr, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chao MP, Tang C, Pachynski RK, Chin R, Majeti R, Weissman IL. Extranodal dissemination of non-Hodgkin lymphoma requires CD47 and is inhibited by anti-CD47 antibody therapy. Blood. 2011;118:4890–901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Xu Z, Guo S, Zhang L, Sharma A, Robertson GP, et al. Intravenous delivery of siRNA targeting CD47 effectively inhibits melanoma tumor growth and lung metastasis. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1919–29. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Z, Chung H, Banan B, Manning PT, Ott KC, Lin S, et al. Antibody mediated therapy targeting CD47 inhibits tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;360:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikuchi Y, Uno S, Kinoshita Y, Yoshimura Y, Iida S, Wakahara Y, et al. Apoptosis inducing bivalent single-chain antibody fragments against CD47 showed antitumor potency for multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2005;29:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiskopf K, Weissman IL. Macrophages are critical effectors of antibody therapies for cancer. MAbs. 2015;7:303–10. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uno S, Kinoshita Y, Azuma Y, Tsunenari T, Yoshimura Y, Iida S, et al. Antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody against CD47 in xenograft models of human leukemia. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:1189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MJ, Lee JC, Lee JJ, Kim S, Lee SG, Park SW, et al. Association of CD47 with natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity of head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:28–34. doi: 10.1159/000132568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murata S, Ladle BH, Kim PS, Lutz ER, Wolpoe ME, Ivie SE, et al. OX40 costimulation synergizes with GM-CSF whole-cell vaccination to overcome established CD8+ T cell tolerance to an endogenous tumor antigen. J Immunol. 2006;176:974–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le DT, Lutz E, Uram JN, Sugar EA, Onners B, Solt S, et al. Evaluation of ipilimumab in combination with allogeneic pancreatic tumor cells transfected with a GM-CSF gene in previously treated pancreatic cancer. J Immunother. 2013;36:382–9. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31829fb7a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2015;348:62–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao MP, Majeti R, Weissman IL. Programmed cell removal: a new obstacle in the road to developing cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:58–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288:2051–4. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French RR, Chan HT, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ. CD40 antibody evokes a cytotoxic T-cell response that eradicates lymphoma and bypasses T-cell help. Nat Med. 1999;5:548–53. doi: 10.1038/8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangsbo SM, Broos S, Fletcher E, Veitonmaki N, Furebring C, Dahlen E, et al. The human agonistic CD40 antibody ADC-1013 eradicates bladder tumors and generates T-cell-dependent tumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1115–26. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy WJ, Welniak L, Back T, Hixon J, Subleski J, Seki N, et al. Synergistic anti-tumor responses after administration of agonistic antibodies to CD40 and IL-2: coordination of dendritic and CD8+ cell responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:2727–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van den Eertwegh AJ, Versluis J, van den Berg HP, Santegoets SJ, van Moorselaar RJ, van der Sluis TM, et al. Combined immunotherapy with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-transduced allogeneic prostate cancer cells and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:509–17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]