Abstract

Background: the impact of sarcopenia on quality of life is currently assessed by generic tools. However, these tools may not detect subtle effects of this specific condition on quality of life.

Objective: the aim of this study was to develop a sarcopenia-specific quality of life questionnaire (SarQoL, Sarcopenia Quality of Life) designed for community-dwelling elderly subjects aged 65 years and older.

Settings: participants were recruited in an outpatient clinic in Liège, Belgium.

Subjects: sarcopenic subjects aged 65 years or older.

Methods: the study was articulated in the following four stages: (i) Item generation—based on literature review, sarcopenic subjects' opinion, experts' opinion, focus groups; (ii) Item reduction—based on sarcopenic subjects' and experts' preferences; (iii) Questionnaire generation—developed during an expert meeting; (iv) Pretest of the questionnaire—based on sarcopenic subjects' opinion.

Results: the final version of the questionnaire consists of 55 items translated into 22 questions rated on a 4-point Likert scale. These items are organised into seven domains of dysfunction: Physical and mental health, Locomotion, Body composition, Functionality, Activities of daily living, Leisure activities and Fears. In view of the pretest, the SarQoL is easy to complete, independently, in ∼10 min.

Conclusions: the first version of the SarQoL, a specific quality of life questionnaire for sarcopenic subjects, has been developed and has been shown to be comprehensible by the target population. Investigations are now required to test the psychometric properties (internal consistency, test–retest reliability, divergent and convergent validity, discriminant validity, floor and ceiling effects) of this questionnaire.

Keywords: sarcopenia, quality of life, questionnaire, older people

Introduction

Sarcopenia is defined by a progressive and generalised loss of muscle mass and function with advancing age [1, 2]. This geriatric syndrome, now recognised as a major clinical problem for older people, is an increasing public health issue in our society [3]. Indeed, sarcopenia is associated with some adverse clinical outcomes such as physical impairment, limitation of mobility, increased risk of falls, hospitalisation and mortality [4–8] but also with major co-morbidities such as type 2 diabetes, obesity and osteoporosis [9].

As of today, the association between sarcopenia and altered quality of life (QoL) has been little studied. Health-related QoL is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. Although the decline in HR-QoL is intuitively evident for sarcopenic subjects, it is only supported by a few studies showing a significant association between, on one side, decreased grip strength and, on the other side, decreased physical and general health [10–12]. Moreover, QoL in these studies has only been measured through generic QoL questionnaires. However, generic tools may not be able to detect subtle effects of a specific condition on QoL. Consequently, a specific tool would be necessary to assess the impact of sarcopenia on QoL. Even if a large number of disease-specific QoL questionnaires currently exist, none are specific to sarcopenia. In the absence of such a specific tool, the ability to clinically characterise QoL in subjects with sarcopenia, as well as the capacity to assess changes over time in the QoL of these subjects seems compromised. Complete assessment of the benefits of a therapeutic intervention should provide evidence of an impact on patients' HR-QoL.

The aim of this study was to develop a sarcopenia-specific QoL questionnaire, called SarQoL (Sarcopenia Quality of Life), designed for community-dwelling elderly subjects aged 65 years and older. In this paper, we describe the four stages of the development of this specific QoL questionnaire.

Methods

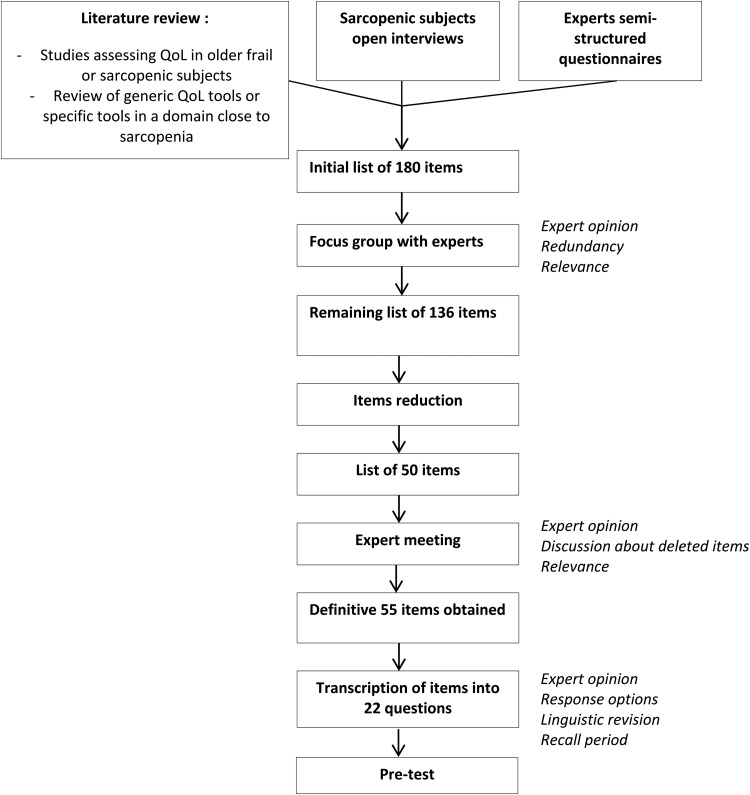

Based on different procedures on how to develop a HR-QoL questionnaire [13–15], but also on experts' recommendations and on many successful studies [16–20], we applied the following four steps to develop our questionnaire (Figure 1):

Step 1. Item generation—based on literature review, sarcopenic subjects' opinion, experts' opinion, focus groups.

Step 2. Item reduction—based on sarcopenic subjects' and experts' relevance ranking.

Step 3. Questionnaire generation—developed during an expert meeting.

Step 4. Pretest of the questionnaire—based on sarcopenic subjects' opinion.

Figure 1.

Overview of study procedures.

Language

The SarQoL questionnaire has been developed in French.

Identification of experts

Different experts (eight from Belgium, one from France and two from Switzerland) were included in the development of this questionnaire: three geriatricians (S.G., J.P., Y.R.), three rheumatologist experts in the field of bone and muscle (E.B., J.Y.R., R.R.), one physiotherapist and Professor in Bio-Gerontology and Geriatric Rehabilitation (I.B.), one linguist expert in the French language (J.V.B.), two experts in methodology of questionnaires (M.J., P.I.) and, at last, one statistician (N.D.).

Identification of patient population

We used the definition of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [21] as criteria for diagnosing sarcopenic subjects. Subjects, aged 65 years and older, were recruited in an outpatient clinic in Liège, Belgium. They are currently enrolled in a 5-year prospective Belgian cohort called SarcoPhAge [22]. Sarcopenia was defined as follows:

– An appendicular lean muscle mass/height2 (SMI) <5.5 kg/m2 for women and <7.26 kg/m2 for men assessed by Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

– A muscle strength <20 kg for women and <30 kg for men assessed by a hydraulic hand dynamometer OR physical performance: ≤8 points for the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test.

Forty-six community-dwelling sarcopenic subjects were recruited in an outpatient clinic in Liège, Belgium. Inclusion criteria included age ≥65 years, French maternal language and written informed consent obtained. Exclusion criteria were amputated limb and BMI above 30 kg/m2.

Subjects had to read and sign an informed consent after having been informed of the objectives and methods of the research. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Teaching Hospital of Liège (number 2013/6).

Step 1: Item generation

Items for the SarQoL were generated in a three-step process. The first step was to draw up, from an exhaustive review of the literature, a comprehensive list of items about QoL in sarcopenia. This list of items was drawn up not only from generic QoL questionnaires intended to either a general population or a population of similar age but also from different studies having assessed the QoL of frail and sarcopenic subjects. This list was then amended after having interviewed five subjects with sarcopenia, in a face-to-face discussion, about how sarcopenia impacts their QoL. All interviews, using open discussion and open-ended questions, were performed by the same clinical researcher (C.B.). During these interviews, sarcopenic subjects described all problems related to sarcopenia that affected their QoL. Answers were transcribed, and a qualitative content analysis of the responses was carried out according to the published methodology [23, 24]. Finally, this list was completed by feedbacks of experts who had received a semi-structured questionnaire, which allowed them to discuss about sarcopenia and its impact on QoL.

Then, the list of items was discussed with the experts in a meeting to reformulate some of them, delete or subdivide others, and, finally, organise them into domains of dysfunction.

Step 2: Item reduction

The aim of this step was to select the most pertinent items to include in the final questionnaire.

To perform this stage, the list of items identified in the generation phase was submitted to 21 sarcopenic subjects, different from those included in Phase 1, and to the experts. They had to grade the relevance of each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1, not relevant’ to ‘4, extremely relevant’. Then, for each item, we examined its ‘frequency’ (the proportion of subjects or experts who identified the item as ‘extremely relevant’) and its importance (the mean importance score based on the Likert scale for this item) and selected items on the basis of the product: frequency × importance. Redundancy of items was also taken into consideration throughout the item reduction process.

Step 3: Development of the questionnaire SarQoL

A focus group was organised with all experts to translate the amended list of items into clear, brief, unambiguous and relevant questions. This meeting also served to define the layout of the questionnaire, the response format and the scoring algorithm. This first version of the questionnaire was submitted to a French linguist to ensure that it was free of any spelling or linguistic errors.

Step 4: Pretest of the questionnaire SarQoL

Once checked by the linguist, the questionnaire was submitted to a sample of 20 sarcopenic patients, different from those included in Stage 1 and Stage 2, to ensure the good understandability of each question and the acceptability of the questionnaire's format. Subjects were invited to express their misunderstanding and to formulate recommendations over the questions. Following this pretest, the second and final version of the questionnaire SarQoL was established.

Statistical analysis

Patient's characteristics are described as median (P25–P75) for continuous variables and count and percentage for categorical variables.

For item reduction, the impact of each item was calculated by multiplying the frequency of an item by its mean importance. This calculation was performed for subjects and for experts separately. The items with an impact of ≥0.5 both for subjects and for experts were selected. Other items were excluded from the list.

All analyses were executed with the software Statistica 9.1.

Results

Patient population

A total of 46 sarcopenic subjects were included in the development of the questionnaire. 78.3% of subjects were women with a mean age of 76.3 ± 6.51 years. Five sarcopenic subjects were included in the phase of items generation, 21 sarcopenic subjects participated in the phase of items reduction and 20 for the pretest. Subjects' characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients involved in Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 4 of the development

| Phase 1: Item generation (n = 5) | Phase 2: Item reduction (n = 21) | Phase 4: Pretest (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.0 (71.0–79.0) | 76.1 (71.6–80.1) | 75.1 (71.7–80.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 5 (100.0) | 13 (61.9) | 18 (90.0) |

| Anthropometric data | |||

| Height (cm) | 161.4 (161.0–166.7) | 161.3 (156.7–168.1) | 157.5 (152.7–162.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 60.3 (50.0–67.5) | 58.3 (53.5–61.8) | 60.0 (55.2–66.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 (17.9–26.0) | 22.2 (20.6–23.7) | 23.8 (23.2–26.9) |

| Calf circumference (cm) | 33.5 (28.0–33.5) | 31.0 (29.5–32.0) | 32.0 (30.0–34.2) |

| Wrist circumference (cm) | 15.0 (15.0–15.5) | 16.0 (15.0–17.0) | 15.5 (15.0–16.5) |

| Arm circumference (cm) | 26.0 (25.0–26.0) | 24.5 (23.0–27.0) | 26.7 (24.7–27.7) |

| Civil status | |||

| Married | 2 (40.0) | 12 (57.1) | 12 (60.0) |

| Divorced | 2 (40.0) | 3 (14.3) | 17 (10.0) |

| Widow | 1 (20.0) | 4 (19.0) | 4 (20.0) |

| Single | 0 (0.00) | 2 (9.52) | 2 (10.0) |

| Level of education | |||

| Without qualification | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Primary school | 3 (60.0) | 2 (9.52) | 2 (10.0) |

| Secondary school | 2 (40.0) | 11 (52.4) | 10 (50.0) |

| Post-secondary education | 0 (0.00) | 8 (38.1) | 8 (40.0) |

| Number of diseases | 2.0 (2.0–7.0) | 5.0 (4.0–8.0) | 4.5 (3.0–6.0) |

| Number of drugs | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 6.0 (5.0–9.0) | 6.0 (5.0–10.0) |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.95 (0.79–0.97) | 0.94 (0.77–1.18) | 0.88 (0.78–1.01) |

| Grip strength maximum (kg) | |||

| Women | 24.6 (20.1–25.3) | 19.5 (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 (16.0–20.5) |

| Men | – | 27.0 (21.5–29.5) | 41.7 (38.0–45.5) |

| SMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Women | 4.97 (4.8–5.3) | 5.07 (4.68–5.35) | 5.31 (4.76–5.46) |

| Men | – | 6.43 (6.21–6.60) | 7.15 (7.10–7.25) |

SMI, skeletal muscle index (appendicular lean mass/height2).

Step 1: Item generation

From the literature review, a first list of 67 items was drawn up. After complementing this list with the open interviews of five sarcopenic subjects and the feedback from the semi-structured questionnaires sent to seven experts (E.B., I.B., S.G., J.P., R.R., J.Y.R., Y.R.), a new list of 180 items was generated. A meeting was then held with all the experts to discuss on the basis of this 180-item list which items had to be deleted because of redundancy, similarity or repetition and which items had to be combined or reformulated. These decisions were made on the basis of consensus agreement between the research team and the experts. At the end of the meeting, the list was reduced to 136 items, structured into eight domains: Physical and Mental Health, Locomotion, Social relations, Body composition, Functionality, Activities of daily living, Leisure activities and Fears.

Step 2: Item reduction

The 136-item list was given to 21 subjects diagnosed sarcopenic and to the experts. Only the items with a frequency × importance product of 0.5 or greater were retained. In three domains, Social relation, Body composition and Fears, no item reached this cut-off point. At this stage, the process reduced the number of items to 48, classified into five domains. Consensus agreement between experts was to keep three items from the domain of Body composition and four items from the domain of Fears and to remove the domain of Social relation from the questionnaire because of its very low score from both patients and experts. The decision of keeping items from the Body composition and Fears domains was based on the fact that the mean rating for these items was >1 for either the experts or the subjects. Following this consensual decision of experts, a final list of 55 items, classified into seven domains was achieved (Table 2).

Table 2.

Presentation of the final 55 items composing the SarQoL questionnaire

| Domains | Items |

|---|---|

| Physical and mental health | Loss of arm strength |

| Loss of leg strength | |

| Loss of energy | |

| Muscle pain | |

| Feeling of muscle weakness | |

| Feeling of being frail | |

| Feeling old | |

| Feeling of being physically weak | |

| Locomotion | Limitation in walking time |

| Limitation in number of outings outdoor | |

| Limitation in walking distance | |

| Limitation in walking speed | |

| Limitation in steps length | |

| Feeling of fatigue when walking | |

| Need of recovery time when walking | |

| Difficulties to cross a road fast enough | |

| Difficulties to walk on uneven grounds | |

| Body composition | Physical change |

| Loss of muscle mass | |

| Weight change (loss or gain) | |

| Functionality | Balance problems |

| Falls occurrence | |

| Loss of physical capacity | |

| Loss of flexibility | |

| Climbing one flight of stairs | |

| Climbing several flight of stairs | |

| Climbing stairs without a banister | |

| Stooping | |

| Crouching or kneeling | |

| To stand from a sitting position | |

| Get up from a chair | |

| To stand up from the floor without any support | |

| Limitation of movement | |

| Sexuality | |

| Activities of daily living | Difficulty during light physical effort |

| Fatigue during light physical effort | |

| Pain during light physical effort | |

| Difficulty during moderate physical effort | |

| Fatigue during moderate physical effort | |

| Pain during moderate physical effort | |

| Difficulty during intensive physical effort | |

| Fatigue during intensive physical effort | |

| Pain during intensive physical effort | |

| Shopping | |

| Household tasks | |

| Carrying heavy objects | |

| Open a bottle or a jar | |

| Take public transportation | |

| To get in/out a car | |

| Leisure activities | Change in physical activities |

| Change in leisure activities | |

| Fears | Fear of getting hurt |

| Fear of not succeeding | |

| Fear of being tired | |

| Fear of falling |

Step 3: Development of the questionnaire SarQoL

The 55 items were translated into 22 questions during a meeting organised with the experts. The decision regarding the format of questions was made by general consent of the experts after discussion. The experts proposed a 4-point Likert scale of frequency (often, sometimes, rarely, never) or intensity (a lot, moderately, a bit, not at all) for all questions at the exception of one question. Seven questions were displayed in a table including several items, and other questions were displayed as unique questions. No question uses a recall period. The total scoring of the SaQoL questionnaire ranges from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health). At this stage, the first version of the SarQoL questionnaire was established.

Step 4: Pretest of the questionnaire SarQoL

Finally, the SarQoL questionnaire was pretested on a group of 20 sarcopenic subjects. It took ∼10 min to patients to self-administer the questionnaire. No patient reported any difficulty in completing the questionnaire or interpreting the questions. The questionnaire was consequently kept unchanged.

Discussion

In the present study, we report the development of the first specific, self-administrated sarcopenia-related QoL questionnaire, the SarQoL questionnaire. This questionnaire includes 55 items translated into 22 questions rated on a 4-point Likert scale. In view of the pretest, the SarQoL is easy to complete, independently, in ∼10 min.

Sarcopenia is associated with the development of physical disability, with nursing home admission, depression, hospitalisation, many co-morbidities, poor physical performance, functional decline, falls and with short- and long-term mortality in hospitalised patients [3]. However, as of today, few studies have assessed the impact of sarcopenia on QoL. In 2012, Kull et al. [11] found a reduced QoL in two domains (i.e. physical function and vitality) of the SF-36 questionnaire in sarcopenic subjects. Two other studies found that sarcopenic subjects presented poorer general health and physical functioning scores [12] and presented significantly more problems of mobility, self-care, usual activity and anxiety than non-sarcopenic subjects [25]. Other studies showed an indirect association between sarcopenia and QoL with a significant correlation between reduced grip strength, one of the components of sarcopenia, and reduced QoL in the domains of physical functioning and general health [10, 26]. Another study also showed a correlation between reduced muscle mass in men and reduced general health, assessed with the SF-36 questionnaire [27]. All these results highlight the fact that QoL of subjects suffering from sarcopenia is affected only in specific domains. Even if the SF-36 is widely in use, simple and effective [28], it is acknowledged that this generic tool should be supplemented with disease-specific instruments [29]. There is a need of a specific QoL questionnaire in the field of sarcopenia [8]. This questionnaire should include the physical aspects of the musculoskeletal domains but should also give an even-handed balance to other factors affecting QoL. During the development of the SarQoL, we followed carefully these recommendations and included therefore no less than seven domains of dysfunction: Physical and Mental Health, Locomotion, Body composition, Functionality, Activities of daily living, Leisure activities and Fears.

HR-QoL assessments are obviously important for healthcare providers and regulatory agencies to understand the needs and preoccupation of important segments of the population, such as elderly subjects suffering from sarcopenia. Such a tool could enhance the accuracy of assessments of well-being and physical function, psychological and social implications of sarcopenic subjects. With the future expected development of interventions targeting sarcopenia, this tool will also be useful to measure the effectiveness and relevance of these new therapeutic strategies.

Our study presents several strengths. First of all, we respected guidelines and followed rigorous steps, which have previously been successfully used in many other studies. Next, many experts have been actively involved in the development process; eight clinician experts in the field of sarcopenia, one linguist expert in the French language, two experts in the methodology of questionnaires and one statistician. This large and heterogeneous panel of experts ensured a rigorous methodology, a good use of the French language throughout the questionnaire and a content validity. Moreover, the content validity was also provided by the large range of sources used to generate items and by the inclusion of sarcopenic patients in the two first stages of the development of the questionnaire, the item generation and the reduction of items. Some weaknesses could however be pointed out. First of all, the inclusion of 46 subjects in the development process could be considered as too limited but is in line with the methodology used in other studies [30, 31]. Secondly, these subjects are also enrolled in another study on sarcopenia (the SarcoPhAge study [22]) and might, consequently, be more aware of the impact of sarcopenia given the participant's information and assessments they underwent for the prospective study. We must also note that the majority of the sample is composed of women, which could have some impact on the results. Moreover, in the item generation phase, all included subjects were women. However, the inclusion of subjects in this phase is not formally requested and only ensures a content validity to the questionnaire. Anyway, we acknowledge that if some men would have been included in this phase, it might have resulted in having some items more specific to men added to the list of items generated. Another limitation is that the questionnaire has only been developed with ambulatory community-dwelling subjects and could not be fully adapted to other populations. Finally, only French-speaking subjects were studied, and characteristics of French-speaking Belgian sarcopenic subjects could differ from subjects from other countries.

Future works

Even if the SarQoL questionnaire is now developed, this questionnaire is not yet ready to be used. Indeed, verification of psychometric properties has still to be done and is currently on the way. Future work includes first the development of a scoring algorithm and a factorial analysis of the included questions; second, the analysis of the convergent and divergent validity of the questionnaire, the internal consistency, the test–retest reliability, and the potential ceiling and floor effects.

Key points.

The generic quality of life tools may not detect subtle effects of sarcopenia on quality of life.

A first version of the SarQoL, a specific quality of life questionnaire for sarcopenic subjects, has been developed.

The SarQoL has been shown to be comprehensible by the target population.

Investigations are now required to test the psychometric properties of this questionnaire.

Conflicts of interest

C.B. and E.B. have received the ‘Young Investigator Research Grant’ for this research from the International Osteoporosis Foundation and Servier. C.B. is supported by a Fellowship from the FNRS (Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique de Belgique—FRS-FNRS—www.frs-fnrs.be).

References

- 1.Cooper C, Dere W, Evans W et al. Frailty and sarcopenia: definitions and outcome parameters. Osteoporos Int 2012; 23: 1839–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147: 755–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyere O et al. Sarcopenia: burden and challenges for Public Health. 2014. Arch Public Health 2014; 72: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol 2003; 95: 1851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen I. Influence of sarcopenia on the development of physical disability: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB et al. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60: 324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang T, Streeper T, Cawthon P et al. Sarcopenia: etiology, clinical consequences, intervention, and assessment. Osteoporos Int 2010; 21: 543–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Arnal JF et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int 2013; 93: 101–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayer AA, Dennison EM, Syddall HE et al. Type 2 diabetes, muscle strength, and impaired physical function: the tip of the iceberg? Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2541–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ et al. Is grip strength associated with health-related quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing 2006; 35: 409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kull M, Kallikorm R, Lember M. Impact of a new sarco-osteopenia definition on health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort in Northern Europe. J Clin Densitom 2012; 15: 32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel HP, Syddall HE, Jameson K et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people in the UK using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS). Age Ageing 2013. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson C, Aaronson NK, Blazeby JM et al. EORTS quality of life group : guidelines for developing questionnaire modules. Eur Organ Res Treat Cancer 2011. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/archives/guidelines_for_developing_questionnaire-_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ 1986; 134: 889–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husson O, Haak HR, Mols F et al. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QoL) for thyroid cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 2013; 52: 447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DunnGalvin A, de BlokFlokstra BM, Burks AW et al. Food allergy QoL questionnaire for children aged 0–12 years: content, construct, and cross-cultural validity. Clin Exp Allergy 2008; 38: 977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storck AJ, Laupland KB, Read RR et al. Development of a Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (HRQL) for patients with Extremity Soft Tissue Infections (ESTI). BMC Infect Dis 2006; 6: 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohtadi NG, Griffin DR, Pedersen ME et al. The development and validation of a self-administered quality-of-life outcome measure for young, active patients with symptomatic hip disease: the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33). Arthroscopy 2012; 28: 595–605; quiz 606–10 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronin L, Guyatt G, Griffith L et al. Development of a health-related quality-of-life questionnaire (PCOSQ) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 1976–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. Sarcopenia: European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaudart C, Reginster JY, Petermans J et al. Quality of life and physical components linked to sarcopenia: The SarcoPhAge study. Exp Gerontol. 2015; 69: 103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krippendorf KL. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Go SW, Cha YH, Lee JA et al. Association between sarcopenia, bone density, and health-related quality of life in Korean men. Korean J Fam Med 2013; 34: 281–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva Neto LS, Karnikowiski MG, Tavares AB et al. Association between sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, muscle strength and quality of life variables in elderly women. Rev Bras Fisioter 2012; 16: 360–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Prestwood KM, Kenny AM. Prevalence of sarcopenia and predictors of skeletal muscle mass in healthy, older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002; 57: M772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Harwood RH et al. The SF-36: a simple, effective measure of mobility-disability for epidemiological studies. J Nutr Heal Aging 2009; 13: 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE., Jr The SF-36 health survey. In: Spilker B, ed. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials, 2nd edition Philadalphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996; 337–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilburn J, McKenna SP, Twiss J et al. Assessing quality of life in Crohn's disease: development and validation of the Crohn's Life Impact Questionnaire (CLIQ). Qual Life Res 2015. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-0947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goh SGK, Rusli BN, Khalid BAK. Development and validation of the Asian Diabetes Quality of Life (AsianDQOL) Questionnaire. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]