Abstract

One of the core symptoms of the menopausal transition is sleep disturbance. Peri-menopausal women often complain of difficulties initiating and/or maintaining sleep with frequent nocturnal and early morning awakenings. Factors that may play a role in this type of insomnia include vasomotor symptoms, changing reproductive hormone levels, circadian rhythm abnormalities, mood disorders, coexistent medical conditions, and lifestyle. Other common sleep problems in this age group, such as obstructive sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome, can also worsen the sleep quality. Exogenous melatonin use reportedly induces drowsiness and sleep and may ameliorate sleep disturbances, including the nocturnal awakenings associated with old age and the menopausal transition. Recently, more potent melatonin analogs (selective melatonin-1 (MT1) and melatonin-2 (MT2) receptor agonists) with prolonged effects and slow-release melatonin preparations have been developed. They were found effective in increasing total sleep time and sleep efficiency as well as in reducing sleep latency in insomnia patients. The purpose of this review is to give an overview on the changes in hormonal status to sleep problems among menopausal and postmenopausal women.

Keywords: Aging, Circadian, Hormone, Melatonin, Menopause, Old, Premenopausal, Perimenopausal, Postmenopausal, Sleep, Women

Introduction

Menopause [(Greek: mene (month); pausis (stop)], defined as the final menstrual period, physiologically results from the natural depletion of ovarian follicular function; a condition that translates into permanent amenorrhea (the permanent cessation of menstrual flow) generally associated with aging [1]. Many women have few or no symptoms, and thus, these women are not necessarily in need of medical treatment. The signs and symptoms of menopause are characterized by onset of irregular menses, hot flushes and night sweats. Menopause is also known to be associated with changes in behavior and other biological functions e.g., mood swings, anxiety, stress, forgetfulness and sleep disturbances [2,3]. During menopause, estrogen levels decline, which may be associated with a corresponding decline in cognitive functioning [2,3] in addition to depressive symptoms and depressive disorders [4]. Some of the clinical features mentioned so far are associated with normal aging; therefore, symptoms that are truly associated with menopause may be difficult to differentiate from those due to aging [5].

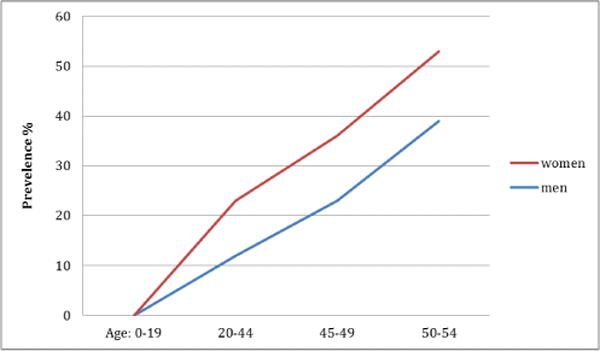

Several lines of evidence suggest that sleep in male and female subjects differs across lifespan, and this may result from the influence of female gonadotropic hormones on sleep [6]. If we compare sleep of women with that of men, women have more sleep complaints as women’s sleep is not only influenced by the gonadotropins themselves, but also by the milestones related to these hormones e.g., pregnancy, which in-turn is associated with physiological changes in other systems [7] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sleep in men and women.

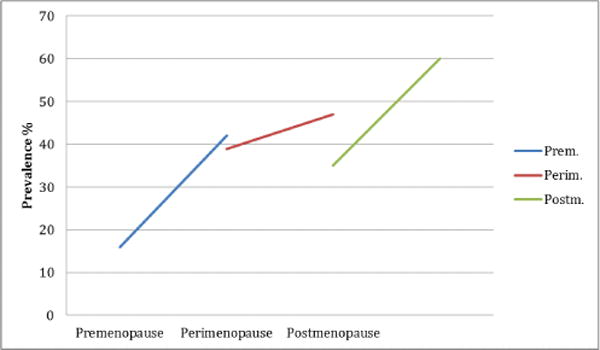

It is therefore not surprising that sleep disturbances are seen during menopause, too [8]. The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN), shows that the prevalence of sleep disturbance increases with increasing age. The prevalence in the premenopausal age group ranges from 16% to 42%; in perimenopausal women prevalence varies from 39% to 47%; in postmenopausal females, the prevalence ranges from 35% to 60% [7]. These disturbances are often multifactorial in origin and they worsen the health-related quality of life [9]. Sleep disturbances among menopausal women have been ascribed to a number of factors e.g., normal physiological changes associated with aging, poor health perception, menopausal-related symptoms, nervousness, stress, mood symptoms (e.g. depression and anxiety), and comorbid chronic health issues [10–13]. Besides these biological and chronobiological factors, socioeconomic, psychosocial, cultural, and race/ethnic factors might also play an interacting role between the sleep and menopause [14,15] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sleep in premenopause, perimenopause, and postmenopause.

Post-menopausal women may have a number of sleep disorders including insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and restless legs syndrome (RLS), to name a few. Having this background in mind, we will try to explore the factors that may be related to the sleep disturbances seen among menopausal women in this review.

Insomnia

Insomnia is a cause for concern in post-menopausal women [16]. The diagnosis of insomnia requires a report of difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, or experiencing no restorative sleep, despite adequate opportunity for sleep. Daytime functional impairments resulting from nocturnal sleep disturbance must also be reported [17]. Notably, polysomnographic studies are not recommended for routine diagnosis of insomnia, as it is a clinical diagnosis. However, in some insomniacs (who fail to respond to treatment), it plays an important role in diagnosis. According to Hachul et al., although early menopause is associated with several symptoms, complaints related to sleep were higher in the late post-menopausal group [16].

It must be noted here that subjectively poor sleep quality does not always represent as poor qulity electrophysiological sleep. This is especially important in this group. Post menopausal women have been found to report subjective poor quality sleep even when the polysomnography examination shows higher amounts of deep sleep and longer sleep times as compared to premanopausal women [18]. Another study compared the sleep polysomnographically among young, premenopausal and post menopausal women. Compared to young women, premenopausal and post menopausal women had lesser sleep efficiency and lesser amount of deep sleep; however, these figure were comparable between premenopausal and post menopausal women [19]. Despite the comparable polysomnographic findings between premenopausal (not young) and post menopausal women, insomnia complaints were more frequent among the latter group. Considering these findings, authors suggetsed that sleep disruption was the function of the age, rather than the menopause status [19]. Contrarily, one study showed longer wake time after sleep and poor sleep efficiecny among post menopausal women as compared to premanopausal women [20]. Thus, it may be concluded that multiple other yet to be found factors, in addiction to manopuse status may affcet the sleep quality in this group.

In coming sections, we try to assess the factors associated with insomnia in this patient group.

Vasomotors Symptoms

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), commonly called ‘hot flashes/hot flushes’, include a feeling of intense heat with tachycardia usually lasting less than 30 minutes for each occurrence. This occurs in the perimenopausal as well as in the menopausal period. While research has focused more on the treatment options, not much is known about the etiology and pathogenesis of these VMS. There is, however, empirical evidence suggesting that reduced estrogen levels could be the primary cause of VMS/hot flashes [21]. Among menopausal and post-menopausal women, VMS is often seen along with menstrual irregularities [2,3], sudden mood changes, irritability, increased stress, forgetfulness, insomnia, depression, anxiety, and lack of concentration. These devastating behavioral changes have a neurobiological basis and literature suggests that changing hormone levels, such a decline in estrogen and an increase in FSH levels, could serve as etiological factors [4,22]. It has been documented that perimenopausal women, relative to pre-menopausal women, complain more about their sleep difficulties and they are higher risk for insomnia [22,23]. Studies have shown that VMS are the primary predictor of sleep problems in menopausal women. Women in this age group have lower sleep efficiency [22]. Their nighttime sleep is characterized by multiple awakenings and they often experience daytime irritability [24,25]. A recent study has directly correlated the difficulty in staying asleep with the presence of VMS in postmenopausal women [26]. Vincent et al. has shown that VMS not only directly and negatively influence sleep, and but also may have an indirect effect on mood, partly mediated by sleep difficulty [27].

However, contradictory literature is also avaibale and there are studies that have questioned the association between VMS and sleep quality or insomnia. In one of these studies, polysomographic findings showed that menopausal women could wake up during the night without hot flashes [28]. Joffe et al. also showed that vasomotor symptoms could be present in the absence of night time awakenings [17]. The findings of an association between vasomotor symptoms and nocturnal awakenings are, therefore, somewhat inconclusive.

Estrogen

Estrogen and sleep quality could have an indirect association as well, mediating through the depressed mood or probably, depression. The declining level of estrogen plays an important role in vaginal dryness that may cause sexual dysfunction. Estrogen decline causes a decrease in the production of vaginal lubrication, loss of vaginal elasticity and thickness of vaginal epithelium (vaginal atrophy), and development of uretheral caruncles [29]. This association of vaginal dryness with sexual dysfunction could be an important psychological factor in depression that eventually leads to sleep disturbance in menopausal and post-menopausal women [30]. Estrogen replacement therapy in menopausal and postmenopausal women has been shown to improve sleep by decreasing night time awakenings. It reduces vaginal dryness and improves sexual dysfunction as well as vasomotor symptoms [31]. However, this theory is too simplistic as we know that all people under stress do not develop depression or insomnia. Similarly, all the patients of depression do not provide a history of stressor antecedant to the onset of depressive symptoms. Thus, we opine that changes in the ovarian hormones may interact with the genetic vulnerability for depression and insomnia and may manifest these symptoms.

Progesterone

Studies also show that decreases in progesterone levels can cause disturbed sleep. Progesterone has both sedative and anxiolytic effects, stimulating benzodiazipine receptors, which play an important role in sleep cycle [32]. However, direct evidence for this theory could not be found in the literature.

Age, Medical Conditions and Sleep

In postmenopausal women, sleep is also disturbed by age related medical conditions, which include obesity, heart problems, gastrointestinal problems, urinary problems, endocrine problems, chronic pain problems, use of neuroactive medications [17], cigarettes, alcohol, caffeinated drinks, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, bronchodilators, antiepileptic medications, thyroid hormones preparations, among others [5]. The exact relationship between these various factors and the post- menopausal period is not quite clear. In persons with genetic vulnerability for insomnia, these factors may act as precipitating or perpetuating factors for insomnia. Pain is an important factor that may lead to sleep disturbances in this group. Poor sleep quality with longer duration sleep has been reported in associated with higher pain scores among women [33]. Rhumatoid arthritis has been found to be asscoaited with poor sleep quality [34]. Biomarkers associated with disease activity e.g., ESR, CRP, radiological damage have been found to be associated with poor sleep quality in addition to the age and depression in this study [34]. Perimenopausal women especially those who are obese have higher chances to wake up with headache at night [35]. These women also have higher chances to have hot flushes and poor sleep quality [35]. During early phase of menopause, backache appears that is associated with poor sleep quality [36]. It is interesting to note that backache, sleep quality and vasomotor symptoms are associated with each other, however, the causal direction is still needs to be established.

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and depression have been noted to be associated with sleep problems in postmenopausal women [37]. Difficulty in initiating sleep has been shown to correlate strongly with anxiety, with nonrestorative sleep also correlating strongly with depression [38]. Difficulty in initiating sleep leads to anxiety, irritability and non-restorative sleep problems which in turn may manifest as depression [38]. One of the major causative factor of depression is insomnia. The low estrogen and progesterone level in menopausal women increase the risk of insomnia and mood disturbances in postmenopausal women. [39].

Studies by Guidozzi et al. showed a significant correlation between depression and sleep related disorders [32]. Thus, treatment of both depression and sleep disturbance is essential regardless of age or menopause status [26].

Treatment of Menopausal Insomnia using Hormone Therapy

Study show if we treat menopausal symptoms earlier after the onset of menopause with estrogen therapy (ET) and combined estrogen-progesterone therapy (EPT) it has more beneficial effects on treating postmenopausal symptoms whereas appearance of breast cancer risk limits its uses somehow.

Estrogen therapy with or without progesterone is very effective in treating vasomotor symptoms (decrease hot flushes) in this way they improve the quality of sleep, HRT is also a one of the major recommended treatment of osteoporosis, sexual dysfunction, mood and depression [40,41].

Study shows HRT effectively treat the depressive symptoms (e.g., sadness, anhedonia, and social isolation in peri-menopausal and postmenopausal women and is the effective treatment of depression in this age group [42,43] Estrogen replacement therapy improves sleep quality by decreasing the frequent nighttime awakenings, it also reduces vasomotor symptoms [44].

When the vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction, osteoporosis, nocturnal awakenings, and depressive symptoms would be improved the quality of sleep will definitely increase in postmenopausal women. So the hormone replacement therapy is one of the recommended treatment in menopausal insomnia, which also not improve the quality of sleep but also the quality of life.

Bazedoxifene/conjugate estrogen (BZA/CE) is a novel estrogen that is tissue selective. This complex has been compared with the placebo in a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial and BZA/CE has been found more effective in control of vasomotor symptoms and improving sleep quality among menopausal women [45]. BZA/CE not only improves the sleep but also is effective in preventing the osteoporosis which can lead to pain complaints and thus worsen sleep quality among these females [45].

Treatment of Menopausal Insomnia using Melatonin

In humans, the circadian rhythm of melatonin release from the pineal gland is highly synchronized with the habitual hours of sleep [46–48]. The daily onset of melatonin secretion is well correlated with the onset of the steepest increase in nocturnal sleepiness (“sleep gate”) [50,51]. Endogenous secretion of melatonin decreases with aging across genders [52], and, among women, menopause is associated with a significant reduction of melatonin levels [53,54]. Exogenous melatonin reportedly induces drowsiness and sleep, and may ameliorate sleep disturbances, including the nocturnal awakenings associated with old age [55–58].

However, existing studies on the hypnotic efficacy of melatonin have been highly heterogeneous with regard to inclusion and exclusion criteria, methods adopted to evaluate insomnia, doses of the medication, and routes of administration. Adding to this complexity, there continues to be considerable controversy over the meaning of the discrepancies that sometimes exist between subjective and objective (polysomnographic) measures of good and bad sleep [59]. Thus, attention has been focused either on the development of more potent melatonin analogs with prolonged effects or on the design of prolonged-release melatonin preparations [60,61]. The MT [1] and MT [2] melatonergic receptor ramelteon [62,63] was found to be effective in increasing total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficiency (SE), as well as in reducing sleep onset latency (SOL) in insomnia patients [64]. The melatonergic antidepressant agomelatine, displaying potent MT [1] and MT [2] melatonergic agonism and relatively weak serotonin 5HT(2C) receptor antagonism [65,66], was found effective in the treatment of insomnia comorbid with depression [67–77]. Other melatonergic compounds are currently under development [71]. In short, melatonergic compounds could be useful in the treatment of insomnia in this group of patients.

Treatment of Menopausal Insomnia using Hypnotics

One four week study has shown improvement in sleep quality, sleep duration and greater reduction in insomnia specific daytime symptoms with the use of zolpidem 10mg/night as compared to placeo in perimenopausal and post-menopausal women [72]. Similar results have been found with the eszopiclone 3mg/night in another study [73].

Restless Legs Syndrome

Originally described first in 1672 by Sir Thomas Willis, the Willis-Ekbom’s disease, or restless legs syndrome (WED/RLS), is more prevalent among women [74,75]. A number of factors including iron deficiency and pregnancy may be responsible for the higher prevalence among females [76]. It has been reported in approximately 18–30% pregnant women [77,78]. In another survey, nearly 15% of women aged 18–64 years were found to have symptoms of WED/RLS; however, its prevalence was unaffected by the menopausal status [79]. Still, menopause can serve to increase the perception of severity of RLS, and thus these women may seek medical help more often [80].

We still do not know how the female hormones influence the expression of WED/RLS across the female life cycle. A number of theories have been proposed that include iron deficiency secondary to pregnancy or persistently high levels of estrogen during pregnancy or fall of estrogen and melatonin at menopause [76,81]. However, theories that were proposed to explain RLS during menopause appear far from reality as manifested by the fact that menopause does not influence the prevalence of WED/RLS and, in most of the cases, hormone replacement therapy does not alter the clinical picture in affected women [76]. On the contrary, one study even refuted the role of female reproductive hormones in the causation of this illness [80].

To contribute to this debate further, one study has reported that female reproductive hormones influence neurotransmission [81]. Estrogen influences the dopaminergic system and not only up-regulates the receptors but also the reuptake mechanism. Further, it also reduces the catabolism of dopamine by inhibitory influence on the Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) enzyme [82]. Thus, it increases the availability of dopamine in the nigro-striatal pathway yet it also increases the reuptake. This might partly explain why some of the studies have found a relationship between RLS and higher prevalence among women. It may be possible that effects of estrogen on dopamine neurotransmission are state dependent. There is also a possibility that estrogen might interact with other hormones such as progesterone, prolactin or iron metabolism in the central nervous system (CNS) which may be state dependent to produce the symptoms of WED/RLS. However, these factors have never been analyzed and this is an area for future research.

A number of studies have proposed that sleep problems associated with menopause, like insomnia, may increase the chances of WED/RLS. It may be possible that women who are not able to fall asleep perceive the increased severity which may have a positive influence on the reporting of symptoms [80,81]. As we have already discussed, sleep difficulties in this group are in part related to vasomotor symptoms. This could be one reason why WED/RLS symptoms have been correlated with the presence of vasomotor symptom among menopausal women in many studies [11,83]. However, one of the recent studies did not find any difference between the sleep difficulties across genders, despite higher prevalence of RLS among females [84]. In addition, although hormone replacement therapy (HRT) improves vasomotor symptoms, this has not been found to influence the WED/RLS in any manner [20,76,79,85].

Considering the above facts, it may be worthwhile to systematically assess the role of HRT in the management of RLS reported by menopausal women.

Menopause and Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) rises markedly after menopause in females [86]. From as low as 47% to as high as 67% post-menopausal women have been found to have OSA across studies [87,88].

Women tend to gain weight after menopause and this results in higher BMI, larger neck circumference and higher waist-hip ratio [87–90] but whether menopause also increases the chances of central obesity is still controversial [90,91]. In this manner, the upper airway becomes anatomically different after menopause and results in compromise in breathing during sleep. Thus, post-menopausal women have a higher prevalence of OSA as compared to pre-menopausal women [89]. However, body weight does not appear to be the only factor responsible for this condition, as another study has found that despite comparable body mass index, post-menopausal women had more severe OSA and they spent a larger amount of sleep time with OSA as compared to pre-menopausal females [92].

Progesterone Role in Partial Upper Airway Obstruction in Postmenopausal Women

Hormonal decrease (progesterone) in postmenopausal woman is one of the causative factor of sleep apnea, due to lack of progesterone the pharyngeal dilator muscle activity is effected and low progesterone could be a causative factor of sleep apnea through the stabilizing effect of decrease respirator drive. And repetitive sleep induced collapse of the pharyngeal airway could happen so the postmenopausal women have higher frequency of apnea than premenopausal women [93,94].

As we have already discussed, menopause is a state of hormonal change and, having this in mind, we should ask ourselves- “what increases the chances of OSA after menopause- direct effect of hormones or the change in anthropometric measures?”. This question was answered by Carskadon et al. who showed that hormonal factors play a minor role as compared to anthropometric measures in development of OSA after menopause [95]. Similar results have been reported in another study where a temporary menopause was initiated with the help of drugs in pre-menopausal women [96] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hormonal disturbances in postmenopausal women and treatment options.

| Hormones | Hormonal Level | Contributes to | Sleep | Recommended Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | ↓ | Anxiety Depression Sexual Dysfunction |

Disturbed Sleep | Hormone therapy | Replacement |

| Progesterone | ↓ | Anxiety Depression Obstructive sleep Apnea |

Disturbed Sleep | Medroxy acetate | progesterone |

| Melatonin | ↓ | Anxiety Depression |

Disturbed Sleep | Melatonin Preparations | |

Besides known cardiovascular complications, OSA is also associated with sexual dysfunction in females [97]. In the pre-menopausal women, time spent below the oxygen saturation of 90% has been found to be associated with sexual dysfunction [98]. Sexual dysfunction has been found to be related to the severity of OSA in both pre-menopausal as well as post-menopausal women [30]. This data suggests that post-menopausal women with OSA should be routinely screened for sexual dysfunction as it may contribute to other sleep problems including insomnia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) as well as Sleep disordered breathing (SDB).

| Group | Sample Size | SDB% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI>10+Symptoms | AHI>15 | Snoring and 0<AHI<15 | Snoring and AHI=0 | ||

| Premenopause | 503 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 7.5 |

| Postmenopause | 497 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 13.0 |

To our knowledge, data is not available whether menopause is related to the compliance of the PAP therapy in those having OSA. Theoretically, there are high chances of poor compliance in post-menopausal women considering the fact that they have poor quality of sleep and are at increased risk of other sleep disorder. This is an area for future research.

Conclusion

We have reviewed the association between sleep disturbances and the menopausal transition. We presented the various morbidities and comorbidities particular to women during this period and how the interplay of these factors impact on sleep. While there is obviously a need for continued research, there are effective behavioral and pharmacological therapies available to treat sleep disturbances at this time in a woman’s life.

The data presented above clearly indicate that exogenous melatonin and its various analogs promote and maintain sleep. However, there is inconsistency and discrepancy among the large number of reports regarding the degree of efficacy and the clinical significance of these effects. Hence, prolonged released melatonin preparations and melatonin agonists were introduced and have shown good results in treating insomnia. So the physiological changes have the great impact on postmenopausal women’s health because these changes cause a clear fall down of certain important hormones of female reproductive system. These vitals Hormones estrogen, progesterone are responsible for the vital reproductive functions of female genital tract, they decrease in postmenopausal women and contribute to anxiety, depression, sexual dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea. There is another important neurohormone melatonin that is found to decrease in postmenopausal women, which also contributes to sleep disturbances and ultimately causes anxiety and depression.

Studies show postmenopausal women experienced maintenance insomnia, because of night sweats and hot flashes more often than premenopausal women, but not initiation insomnia [99], this maintenance insomnia is due to vasomotor hot flashes due to lack of estrogen. Progesterone has a respiratory stimulant properties and it maintains the tone of a genioglossus muscles, in postmenopausal women due to lack of this hormone women’s chances to get into sleep apnea increases, so it causes more sleep problems.

Further investigations by randomized controlled studies to evaluate the efficacy of these interventions in peri-post menopausal women are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the following funding agencies: R25-HL105444 and R25-HL116378 (NHLBI); R01-MD007716 (NIMHD) to GJL. However, the funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Freedman RR., 1 Postmenopausal physiological changes. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;21:245–256. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twiss JJ, Wegner J, Hunter M, Kelsay M, Rathe-Hart M, et al. Perimenopausal symptoms, quality of life, and health behaviors in users and nonusers of hormone therapy. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19:602–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber MT, Rubin LH, Maki PM. Cognition in perimenopause: the effect of transition stage. Menopause. 2013;20:511–517. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31827655e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt PJ., 1 Mood, depression, and reproductive hormones in the menopausal transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidozzi F., 1 Sleep and sleep disorders in menopausal women. Climacteric. 2013;16:214–219. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.753873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsleben JA., 1 Women and sleep. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;98:639–651. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52006-7.00040-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kravitz HM, Joffe H. Sleep during the perimenopause: a SWAN story. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:567–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichling PS, Sahni J. Menopause related sleep disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on Management of Menopause-Related symptoms. 2005:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albuquerque RG, Hachul H, Andersen ML, Tufik S. The importance of quality of sleep in menopause. Climacteric. 2014;17:613. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.888713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hachul H, Andersen ML, Bittencourt LR, Santos-Silva R, Conway SG, et al. Does the reproductive cycle influence sleep patterns in women with sleep complaints? Climacteric. 2010;13:594–603. doi: 10.3109/13697130903450147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun D, Shao H, Li C, Tao M., 2 Sleep disturbance and correlates in menopausal women in Shanghai. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno-Frías C, Figueroa-Vega N, Malacara JM. Relationship of sleep alterations with perimenopausal and postmenopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2014;21:1017–1022. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ornat L, Martínez-Dearth R, Chedraui P, Pérez-López FR., 3 Assessment of subjective sleep disturbance and related factors during female mid-life with the Jenkins Sleep Scale. Maturitas. 2014;77:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hachul H, Bittencourt LR, Soares JM, Jr, Tufik S, Baracat EC. Sleep in post-menopausal women: differences between early and late post-menopause. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joffe H, Massler A, Sharkey KM. Evaluation and management of sleep disturbance during the menopause transition. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:404–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, Austin D, Laurel F. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 2003;26:667–672. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalleinen N, Polo-Kantola P, Himanen SL, Alhola P, Joutsen A, et al. Sleep and the menopause - do postmenopausal women experience worse sleep than premenopausal women? Menopause Int. 2008;14:97–104. doi: 10.1258/mi.2008.008013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu M, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Guay B, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of subjective and objective sleep quality in menopausal and non-menopausal women with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2011;12:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Safi ZA, Santoro N., 2 Menopausal hormone therapy and menopausal symptoms. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berecki-Gisolf J, Begum N, Dobson AJ. Symptoms reported by women in midlife: menopausal transition or aging? Menopause. 2009;16:1021–1029. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a8c49f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kronenberg F., 1 Hot fashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kronenberg F., 1 Menopausal hot fashes: a review of physiology and biosociocultural perspective on methods of assessment. J Nutr. 2010;140:1380S–5S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.120840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lampio L, Polo-Kantola P, Polo O, Kauko T, Aittokallio J, et al. Sleep in midlife women: effects of menopause, vasomotor symptoms, and depressive symptoms. Menopause. 2014;21:1217–1224. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent AJ, Ranasinha S, Sayakhot P, Mansfield D, Teede HJ. Sleep difficulty mediates effects of vasomotor symptoms on mood in younger breast cancer survivors. Climacteric. 2014;17:598–604. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.900745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurston RC, Chang Y, Mancuso P, Matthews KA. Adipokines, adiposity, and vasomotor symptoms during the menopause transition: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Fertil Steril. 2012;100:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:87–94. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stavaras C, Pastaka C, Papala M, Gravas S, Tzortzis V, et al. Sexual function in pre- and post-menopausal women with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int J Impot Res. 2012;24:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Irjala K, Pullinen S, Virtanen I, et al. Effect of short-term transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on sleep: a randomized, double-blind crossover trial in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:873–880. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidozzi F, Alperstein A, Bagratee JS, Dalmeyer P, Davey M, et al. South African Menopause Society revised consensus position statement on menopausal hormone therapy, 2014. S Afr Med J. 2014;104:537–543. doi: 10.7196/samj.8423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kravitz HM, Zheng H, Bromberger JT, Buysse DJ, Owens J, et al. An actigraphy study of sleep and pain in midlife women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Sleep Study. Menopause. 2015;22:710–718. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Bozkurt M, Bez Y, Cetincakmak MG, et al. Sleep quality in rheumatoid arthritis: relationship between the disease severity, depression, functional status and the quality of life. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6:44–52. doi: 10.4021/jocmr1648w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucchesi LM, Hachul H, Yagihara F, Santos-Silva R, Tufik S, et al. Does menopause influence nocturnal awakening with headache? Climacteric. 2013;16:362–368. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.717997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Pain symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Climacteric. 2010;13:467–478. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.483025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry BL, Fernando Martinez L, Maurer EL, Lopez AM, Sorenson D. Sleep, rhythms and women’s mood. Part II. Menopause Sleep Med Rev. 2010;10:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terauchi M, Hiramitsu S, Akiyoshi M, Owa Y, Kato K, et al. Associations between anxiety, depression and insomnia in peri- and post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 2012;72:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landis CA, Moe KE. Sleep and menopause. Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;39:97–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnabei VM, Grady D, Stovall DW, Cauley JA, Lin F, et al. Menopausal symptoms in older women and the efects of treatment with hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Kim J, Ford D, Lawton BA, et al. Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Roca CA, et al. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:414–420. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santoro N, Epperson CN, Mathews SB., 2 Menopausal Symptoms and Their Management. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015;44:497–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Irjala K, Pullinen S, Virtanen I, et al. Effect of short-term transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on sleep: a randomized, double-blind crossover trial in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:873–880. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Racketa J, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:18–28. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandi-Perumal SR, Srinivasan V, Maestroni GJ, Cardinali DP, Poeggeler B, et al. Melatonin: Nature’s most versatile biological signal? FEBS J. 2006;273:2813–2838. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandi-Perumal SR, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Cardinali DP. Role of the melatonin system in the control of sleep: therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:995–1018. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srinivasan V, Spence WD, Pandi-Perumal SR, Zakharia R, Bhatnagar KP, et al. Melatonin and human reproduction: shedding light on the darkness hormone. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:779–785. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srinivasan V, Spence WD, Pandi-Perumal SR, Zakharia R, Bhatnagar KP, et al. Melatonin and human reproduction: shedding light on the darkness hormone. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:779–785. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brzezinski A., 1 Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:186–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shochat T, Haimov I, Lavie P. Melatonin–the key to the gate of sleep. Ann Med. 1998;30:109–114. doi: 10.3109/07853899808999392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haimov I, Lavie P, Laudon M, Herer P, Vigder C, et al. Melatonin replacement therapy of elderly insomniacs. Sleep. 1995;18:598–603. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.7.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toffol E, Kalleinen N, Haukka J, Vakkuri O, Partonen T, et al. Melatonin in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: associations with mood, sleep, climacteric symptoms, and quality of life. Menopause. 2014;21:493–500. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a6c8f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vakkuri O, Kivelä A, Leppäluoto J, Valtonen M, Kauppila A. Decrease in melatonin precedes follicle-stimulating hormone increase during perimenopause. Eur J Endocrinol. 1996;135:188–192. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandi-Perumal SR, Seils LK, Kayumov L, Ralph MR, Lowe A, et al. Senescence, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:559–604. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhdanova IV, Lynch HJ, Wurtman RJ. Melatonin: a sleep-promoting hormone. Sleep. 1997;20:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhdanova-IV FL. Melatonin for Treatment of Sleep and Mood Disorders. In: Mischoulon D, Rosenbaum J, editors. Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives. Lippincot, Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Attarian H, Hachul H, Guttuso T, Phillips B. Treatment of chronic insomnia disorder in menopause: evaluation of literature. Menopause. 2015;22:674–684. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nowell PD, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA. 1997;278:2170–2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lemoine P, Nir T, Laudon M, Zisapel N. Prolonged-release melatonin improves sleep quality and morning alertness in insomnia patients aged 55 years and older and has no withdrawal effects. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:372–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lemoine P, Zisapel N. Prolonged-release formulation of melatonin (Circadin) for the treatment of insomnia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:895–905. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.667076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K, Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, et al. Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto M., 1 Pharmacology of ramelteon, a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist: a novel therapeutic drug for sleep disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15:32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pandi-Perumal SR, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Moscovitch A, Hardeland R, et al. Ramelteon: a review of its therapeutic potential in sleep disorders. Adv Ther. 2009;26:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hardeland R, Poeggeler B, Srinivasan V, Trakht I, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Melatonergic drugs in clinical practice. Arzneimittelforschung. 2008;58:1–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Dekeyne A, Newman-Tancredi A, et al. The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:954–64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Srinivasan V, De Berardis D, Shillcutt SD, Brzezinski A. Role of melatonin in mood disorders and the antidepressant effects of agomelatine. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1503–1522. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.711314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kennedy SH, Emsley R. Placebo-controlled trial of agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Llorca PM., 1 The antidepressant agomelatine improves the quality of life of depressed patients: implications for remission. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:21–26. doi: 10.1177/1359786810372978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Srinivasan V, Brzezinski A, Pandi-Perumal SR, Spence DW, Cardinali DP, et al. Melatonin agonists in primary insomnia and depression-associated insomnia: are they superior to sedative-hypnotics? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zlotos DP, Jockers R, Cecon E, Rivara S, Witt-Enderby PA. MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: ligands, models, oligomers, and therapeutic potential. J Med Chem. 2014;57:3161–3185. doi: 10.1021/jm401343c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dorsey CM, Lee KA, Scharf MB. Effect of zolpidem on sleep in women with perimenopausal and postmenopausal insomnia: a 4-week, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2004;26:1578–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soares CN, Joffe H, Rubens R, Caron J, Roth T, et al. Eszopiclone in patients with insomnia during perimenopause and early postmenopause: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1402–1410. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245449.97365.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Agarwal P. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in North American and Western European populations: a systematic review. Sleep Med. 2011;12:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ohayon MM, O’Hara R, Vitiello MV. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manconi M, Ulfberg J, Berger K, Ghorayeb I, Wesström J, et al. When gender matters: restless legs syndrome. Report of the “RLS and woman” workshop endorsed by the European RLS Study Group. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vahdat M, Sariri E, Miri S, Rohani M, Kashanian M, et al. Prevalence and associated features of restless legs syndrome in a population of Iranian women during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Minar M, Habanova H, Rusnak I, Planck K, Valkovic P. Prevalence and impact of restless legs syndrome in pregnancy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wesstrom J, Nilsson S, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Ulfberg J. Restless legs syndrome among women: prevalence, co-morbidity and possible relationship to menopause. Climacteric. 2008;11:422–428. doi: 10.1080/13697130802359683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ghorayeb I, Bioulac B, Scribans C, Tison F. Perceived severity of restless legs syndrome across the female life cycle. Sleep Med. 2008;9:799–802. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Viola-Saltzman M, Watson NF, Bogart A, Goldberg J, Buchwald D. High prevalence of restless legs syndrome among patients with fibromyalgia: a controlled cross-sectional study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:423–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Attarian HV-SM. editors Sleep Disorders in Women: A Guide to Practical Management, 2 edn Totowa. Humana; 2013. p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Attarian HV-SM. editors Sleep Disorders in Women: A Guide to Practical Management, 2 edn Totowa. Humana; 2013. p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gupta R, Goel D, Ahmed S, Dhar M, Lahan V., 4 What patients do to counteract the symptoms of Willis-Ekbom disease (RLS/WED): Effect of gender and severity of illness. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17:405–408. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.144010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Reed SD, Ensrud KE, et al. Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1058–1066. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips T, Symons J, Menon S, et al. Does hormone therapy improve age-related skin changes in postmenopausal women? A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo controlled multicenter study assessing the effects of noethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol in the improvement of mild to moderate age-related skin changes in postmenopausal women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dancey DR, Hanly PJ, Soong C, Lee B, Hoffstein V. Impact of menopause on the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea. Chest. 2001;120:151–155. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Resta O, Bonfitto P, Sabato R, De Pergola G, Barbaro MP. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea in a sample of obese women: effect of menopause. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2004;17:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Resta O, Caratozzolo G, Pannacciulli N, Stefàno A, Giliberti T, et al. Gender, age and menopause effects on the prevalence and the characteristics of obstructive sleep apnea in obesity. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2003.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Donato GB, Fuchs SC, Oppermann K, Bastos C, Spritzer PM. Association between menopause status and central adiposity measured at different cutoffs of waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Menopause. 2006;13:280–285. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000177907.32634.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gambacciani M, Ciaponi M, Cappagli B, Benussi C, De Simone L, et al. Climacteric modifications in body weight and fat tissue distribution. Climacteric. 1999;2:37–44. doi: 10.3109/13697139909025561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anttalainen U, Saaresranta T, Aittokallio J, Kalleinen N, Vahlberg T, et al. Impact of menopause on the manifestation and severity of sleep-disordered breathing. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1381–1388. doi: 10.1080/00016340600935649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Popovic RM, White DP. Upper airway muscle activity in normal women: influence of hormonal status. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1055–1062. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.3.1055. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anttalainen U, Polo O, Vahlberg T, Saaresranta T. Women with partial upper airway obstruction are not less sleepy than those with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:873–876. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0735-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carskadon MA, Bearpark HM, Sharkey KM, Millman RP, Rosenberg C, et al. Effects of menopause and nasal occlusion on breathing during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:205–210. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.D’Ambrosio C, Stachenfeld NS, Pisani M, Mohsenin V. Sleep, breathing, and menopause: the effect of fluctuating estrogen and progesterone on sleep and breathing in women. Gend Med. 2005;2:238–245. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(05)80053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Subramanian S, Bopparaju S, Desai A, Wiggins T, Rambaud C, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:59–62. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fanfulla F, Camera A, Fulgoni P, Chiovato L, Nappi RE. Sexual dysfunction in obese women: does obstructive sleep apnea play a role? Sleep Med. 2013;14:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lampio L, Saaresranta T, Polo O, Polo-Kantola P. Subjective sleep in premenopausal and postmenopausal women during workdays and leisure days: a sleep diary study. Menopause. 2013;20:655–660. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31827ae954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]