Abstract

This article describes the development of a dynamic culturally constructed clinical practice model for HIV/STI prevention, the Narrative Intervention Model (NIM), and illustrates its application in practice, within the context of a 6-year transdisciplinary research program in Mumbai, India. Theory and research from anthropology, psychology, and public health, and mixed-method ethnographic research with practitioners, patients, and community members, contributed to the articulation of the NIM for HIV/STI risk reduction and prevention among married men living in low-income communities. The NIM involves a process of negotiation of patient narratives regarding their sexual health problems and related risk factors to facilitate risk reduction. The goal of the NIM is to facilitate cognitive-behavioral change through a three-stage process of co-construction (eliciting patient narrative), deconstruction (articulating discrepancies between current and desired narrative), and reconstruction (proposing alternative narratives that facilitate risk reduction). The NIM process extends the traditional clinical approach through the integration of biological, psychological, interpersonal, and cultural factors as depicted in the patient narrative. Our work demonstrates the use of a recursive integration of research and practice to address limitations of current evidence-based intervention approaches that fail to address the diversity of cultural constructions across populations and contexts.

Keywords: Cultural construction, Clinical practice, HIV/STI prevention, Evidence-based practice, Narrative intervention model

Introduction

Development of biomedical, public health, and psychological interventions that meet the needs of a diverse global population has been hampered by the translation of theories and research findings without suitable consideration of cultural and contextual factors (Gaines 2011; Sue 1999). Even medical anthropology, despite its emphasis on integrating culture with medicine, has been criticized for embracing “informal biomedical discursive practices encouraging the portability of decontexted [sic] knowledge” (Gaines 2011, p. 83). Evidence-based practice (i.e., using interventions that have been subjected to experimental validation) is often confused with the search for the ‘one-size-fits-al1’, the universal intervention for all individuals across all contexts. Exacerbating the confusion is the acceptance of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as the benchmark for validating interventions and the related emphasis on internal validity at the expense of external validity (Ingraham and Oka 2006; Sue 1999; WHO 2004). The level of experimental control in RCTs limits attention to the potential variations in real-life settings related to contextual, cultural, and individual factors, thus restricting translation to practice. Recognition of these limitations has resulted in calls for research in social, behavioral, and health sciences on the “effectiveness of implementation strategies and procedures as they are actually used in practice” (Fixsen et al. 2005, p. 75). Even when researchers attempt to address cultural factors, the result can be niche standardization (Epstein 2007; Shaw and Armin 2011) or the development of interventions that apply to categorical groups (e.g., specific ethnic or racial group) without attention to the heterogeneity of the group or dynamic nature of culture.

So the question remains: How do we develop evidence-based models to guide interventions that are sensitive to local culture and context and to individuals as well as the groups with which they are affiliated? We address this question in the context of a large-scale community-based intervention study focused on the prevention of HIV/STIs and sexual risk in low-income communities in Mumbai, India.1 Our goal was to develop an approach to practice that would be (a) informed by research; (b) culturally co-constructed by married men, medical practitioners, and social scientists; and (c) adaptable to individual infra-cultural variations, that is, adaptable for use by different practitioners across a variety of patients. Our assumption was that by starting with the concerns of married men about sexual and relational health, we collectively could address both sexual health and STI/HIV prevention through an indigenous cultural lens, consistent with the work of Beihl (e.g., Biehl et al. 2007). In addition, we wanted to develop a dynamic practice model that could allow for tailoring at the individual level through joint problem solving between individual practitioners and patients. We used a transdisciplinary and participatory approach, characterized by the integration of theories, research, and practices across multiple disciplines as negotiated by scientists, practitioners, and community members as partners (e.g., Leff et al. 2004; Nastasi et al. 2004; Nastasi et al. 1998–99; Schensul et al. 2006a, b, c; Stein et al. 2002).

We use the term cultural (co-)construction to refer to the process of dialog among equal partners across class, ethnic/racial, disciplinary, cultural, and other boundaries that integrates knowledge, values, perspectives, and methods derived from all parties, resulting in shared innovation. The co-construction of cultural and other forms of knowledge is an ongoing process that reflects the nature of participatory research and intervention development and the more dynamic nature of the social construction of illness and treatment within medical practice (Kleinman et al. 1978). We prefer the term cultural (co-)construction to the more static contemporary concepts for addressing culture in practice, such as culturally sensitive, culturally appropriate, culturally specific, culturally competent, or culturally relevant.

To illustrate these ideas, we describe the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of a culturally co-constructed clinical practice model we labeled the Narrative Intervention Model (NIM) and illustrate its application in the conduct of a sexual risk prevention program with married men seeking care in urban health care settings in Mumbai, India. The NIM as a practice model was adopted by local doctors, practicing either western biomedical (allopathic) or Indian Systems of Medicine (ISM), as part of their treatment of men presenting with sexual health concerns. Following a 2½-year training and consultation program, the local doctors had not only integrated the approach into their treatment of men’s sexual health problems, but also applied the NIM to treatment of a range of general health concerns, thus broadening their focus of medical treatment to include social, cultural, interpersonal, psychological, and biological/physiological factors. In this article, we describe the foundations and development of the NIM, the process of implementation in low-income urban communities of Mumbai, and illustrate its use in clinical practice for STI/HIV prevention within the treatment of men’s sexual health concerns.

Transdisciplinary Model: Integrating Anthropology, Psychology, and Public Health

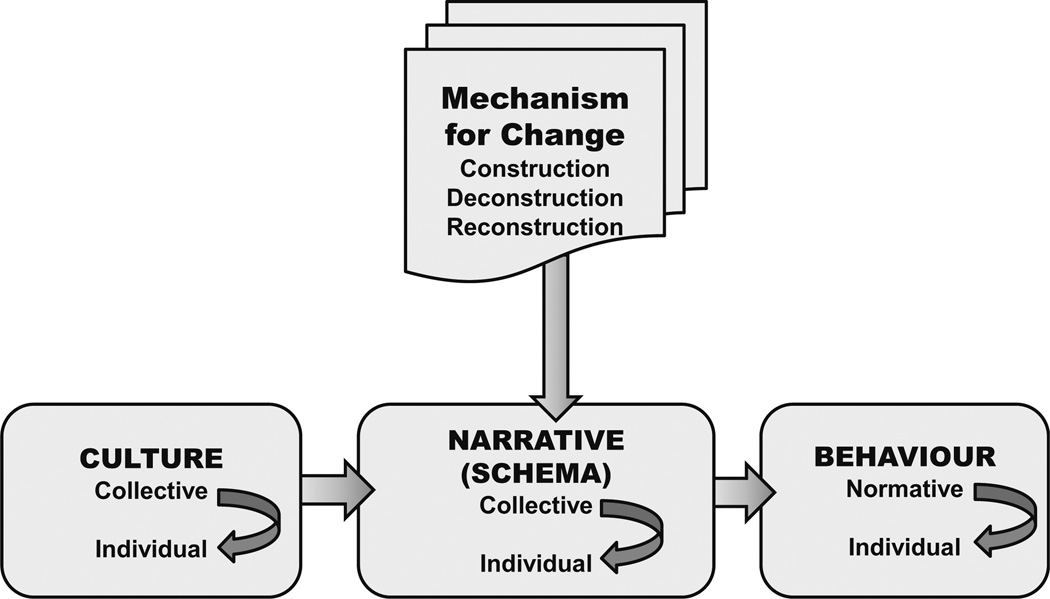

Co-constructing a transdisciplinary model of health risk and behavior change required integration of theoretical, empirical, and methodological foundations from anthropology, psychology, and public health. Figure 1 depicts the transdisciplinary model of change for the Narrative Intervention Model. In brief, culture at the collective and individual level interacts with cognitive or narrative schema reflected in interpersonal or personal narratives, which in turn affects behavior at group and individual levels. Culture, schema, and behavior are in constant dynamic interaction while at the same time engaging with and responding to the economic, political, and situational factors that shape community life. Targeted cognitive-behavioral change occurs through a guided or facilitated process of cultural construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of personal narratives that guide behavior, in this case, behavior related to sexual risk. In this section, we draw on the foundations from anthropology, psychology, and public health to delineate the key terms and processes depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Culturally constructed model of change. This figure depicts the model of change for the Narrative Intervention Model (NIM), with foundations in anthropology, psychology, and public health. Culture at the collective and individual level interacts with cognitive or narrative schema reflected in interpersonal or personal narratives, which in turn affects behavior at group and individual levels. Targeted cognitive-behavioral change occurs through a facilitated process of cultural construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of personal narratives that guide behavior, in this case, behavior related to sexual risk

Cognitive Construction and Role of Culture

Based on writings in anthropology (e.g., Bibeau and Corin 1995; Geertz 1992), we defined culture as a system of meaning, knowledge, and action. As a system of meaning, culture influences how humans collectively, interpersonally, and individually interpret or make sense of their interactions with the physical and social environment. As a system of knowledge, culture legitimizes normative behaviors and other socially acceptable ways of acting. As a system of action, culture is a dynamic process (Matsumoto 1996) of social construction, analysis/deconstruction, and reconstruction in which meanings are continually negotiated or transformed among members of a given group. Culture also can be conceived of as a repertoire of “tools” (ideas, beliefs, rituals, scripts, and norms), which are available for guiding actions (Hannerz 1990). Although culture may be viewed as driving behaviors or actions, Shweder (1999) among others has observed that this direction persists during stable periods or situations, but that instability produces opportunities for innovation through actions which in turn contribute to the development of new cultural options. The transmission and continuity of culture and its institutions depend on such transformations and the emergence of new cultural meanings (e.g., Bourdieu 1980; Sahlins 1989) in the context of ever-changing circumstances that require development of new behavioral strategies underpinned by new explanatory models. Such changes can stem from alterations in the physical, social, and political environment resulting from occurrences such as major disasters, migration, economic growth or decline, political revolution, or change in policies. These conceptions of culture are consistent with our focus on depicting cultural co-construction as a dynamic process that occurs at collective (e.g., community, group, professional disciplinary), individual (e.g., practitioner), and dyadic (e.g., patient-practitioner dyad) levels. Furthermore, culture is reflected in the shared meanings of a collective, whereas variations in cultural responses occur based on individual interpretations or narratives of its members.

Other transdisciplinary theoretical framework also reflects the dynamic nature of culture and the interaction of culture with contextual factors. Bronfenbrenner’s (1999) ecological systems theory emphasizes the dynamic interaction of the person-environment relationship and the importance of collective and individual representations of culture and context. He argues that human development and cultural transmission occur through a dynamic and synergistic relationship between the individual and the physical and social environment. The assumption of collective and individual interpretations of culture also is consistent with the delineation of cognitive scripts as cultural (i.e., collective; widely shared understandings), interpersonal (i.e., dyadic; between two people in a given setting), and intrapsychic (i.e., individual; see Simon and Gagnon 1986, 1999; Shore 1996). For all three types of scripts, change occurs through continuous interaction. And context plays an important role in shaping the interactional process that links culture and interactional and individual behavior and its interpretation.

For our purposes, we conceptualize culture as a dynamic system of meanings, knowledge, and actions that provides actors collectively, interpersonally, and individually with community-legitimized strategies to construct, reflect upon, and reconstruct their world and experience, and guide behavior. Thus, at a cultural or community level, we sought to understand shared cultural meanings, culturally sanctioned behavior, and interactions between practitioners and their patients. At the dyadic doctor–patient level, we sought to understand the cultural co-construction process that reflects assessment, diagnosis, and treatment in the context of medical care. At the individual level, we sought to understand the interaction of cognitive schemas, reflected in personal narratives (e.g., of patients or doctors), with context and cultural experiences. Most importantly, we strove to understand how we might influence the doctor–patient cultural construction process in vivo to effect change in cognitive schema of the patient which in turn would lead to behavioral change consistent with health promotion and risk reduction.

Our approach was operationalized in low-income settings in urban India, where providers of Indian Systems of Medicine (ISM) faced the constraints of practicing healing without full access to the resources of traditional healing practices learned in Ayurvedic, Unani, or homeopathic medical schools; allopathic (biomedical) providers lacked the flexibility to adapt their treatment and practices to local cultural beliefs outside the allopathic tradition. ISM providers were able to obtain only limited formal education on Indian medical traditions which had been replaced by western allopathic medicine. In the transition, the holistic approach to healing typical of these traditions was for the most part lost and many ISM providers treated their patients with injections, pills, and other western prescriptive medicines rather than considering illness in the context of lived experience and life challenges including structural violence. Allopathic providers were constrained by lack of access to needed medications and holistic assessment of presenting health problems that was not part of their tradition. Both groups of providers were constrained by the circumstances of their practice in communities with limited economic resources and were required to see many patients over a short period of time, leaving little time for holistic approaches. Nonetheless, they were, in each case, central resources when family members became ill. Furthermore, these practitioners were the sole points of contact for men experiencing social suffering presented in the form of sexual dysfunction or biological symptoms, collectively labeled as gupt rog, or secret illness in Hindi and Urdu. This cluster of symptoms became the focus of our intervention.

Our understanding of gupt rog and its identification as a marker for men’s sexual risk was derived from our extensive formative ethnographic research (Schensul et al. 2007, 2009a, b). Gupt rog refers to a range of presenting symptoms, as varied as early ejaculation, semen loss related to masturbation or nocturnal emission, erectile dysfunction, weakness, pus discharge, and blisters on the genitals, which could be indicative of STIs or sexual dysfunction. Gupt rog also can be interpreted as a reflection of loss of control over masculinity as expressed in household support and ensuring women’s compliance with patriarchal norms. Coping strategies for sexual dysfunction are excessive drinking, spending time and money with male friends, and seeking outside sexual partners. The presenting problems, central to gender relationships and sexuality in Indian communities, are an embodied expression of social suffering and lack of agency in managing economic, household, and relationship circumstances in the economically, socially, and politically stressful environment characteristic of urban slum communities (Das and Das 2007). Biehl and others note the importance of establishing and maintaining agency in the face of overwhelming structural challenges (Biehl et al. 2007; Biehl and Petryna 2013a, b). Identification of acceptable and effective ways of expressing agency in such settings is an important component of any culturally based (or culturally constructed) intervention (Biehl and Petryna 2013a, b; Whyte et al. 2013).

Cultural Construction of Cognitive Schema

To enhance our conceptual understanding of the interplay of the social-cultural environment with cognition and behavior, we turned to social constructivist and social psychological perspectives from psychology (e.g., Fisher and Fisher 1993; Vygotsky 1978; Wertsch 1991), sociology (Berger and Luckmann 1966), and anthropology (Geertz 1992). Whereas psychological theories focus on development of cognitions (schemas) and cognitive-behavioral connections at an individual level, anthropological and sociological theories focus on interactions of shared (collective) and individual schemas as mechanisms for cultural transmission and individual interpretations of reality (e.g., day-to-day experiences). At the individual level, construction occurs through interaction with the social-cultural environment and helps to explain individual development of schemas or scripts to guide behavior such as sexual behavior. At a dyadic or group level, the process is co-constructive, occurring through interaction with significant or influential others. A major premise of these theories is that language and cognition are developed or transmitted through social interactions during which meaning is co-constructed and through which individuals construct personal models of reality, that is, individual interpretations of experiences. Ideally, growth or change requires some degree of challenge or disagreement with the current cognitive schema; this conflict of ideas or cognitions forces a process of deconstruction (critical examination of current cognitions) and reconstruction (reformulation) to accommodate the discrepant information. Thus, deliberate attempts to change cognitions and related behaviors could involve a process of facilitated construction-deconstruction-reconstruction at collective, dyadic, or individual levels.

Facilitating Cognitive Change through Co-construction: Applications to Clinical Practice

In parallel to the theoretical formulation for good clinical practice, we proposed a construction–deconstruction–reconstruction process that emulates the processes inherent in psychological and anthropological explanations of cultural transmission and human behavior. That is, individual schemas, or belief systems, are influenced by the individual’s social-cultural experiences. Collective schemas, or shared cognitive rituals, norms, and beliefs, reflect the collective interaction, negotiation, and integration of cultural experiences and belief systems of many individuals. In the context of clinical practice, co-constructed schemas evolve through the interaction of clinicians and patients in a specific microsystem such as the doctor’s clinic. Formulating a co-constructed culturally based approach necessitates consideration of the individual and collective schemas or explanatory models of both practitioners and patients and negotiation of the dyadic schema.

Consistent with our conceptualization of schema as ‘narrative’ or story, we drew from narrative models of clinical practice with foundations in medical anthropology and counseling/clinical psychology, and risk reduction models in public health. These models are consistent with social constructivist explanations of cognitive-behavior change and rely on the construction-deconstruction-reconstruction of narratives as the foundation of culturally constructed and culturally competent clinical practice. Kleinman, for example, proposed an explanatory model of medical practice (Kleinman 1988a, b, 1992; Kleinman and Benson 2006) that involves the application of ethnographic methods, through the mini-ethnographic interview, to generate explanatory models of presenting health concerns that reflect the cultural meaning of illness for the patient and the practitioner, and provide the basis for developing a shared explanatory model to guide diagnosis and treatment. Lo (2010) further characterizes the patient–practitioner interaction as a process of negotiating schemas, or cultural brokerage, with the practitioner serving as the broker. DasGupta et al. (2006) used literary-based case studies (narratives) that depicted cultural conflicts of individual patients and medical practitioners to facilitate cultural sensitivity and awareness of both local and medical culture, and to effect attitudinal and behavioral changes related to clinical practice among medical residents. Narrative approaches to clinical practice and training of practitioners also are evident in narrative therapy for individuals and married couples (Botella and Herrero 2000; Brimhall et al. 2003; Eron and Lund 1996; Petraglia 2007; Rothschild et al. 2000; White and Epston 1989, 1990), intentional interviewing and counseling (Ivey et al. 2010), motivational interviewing (Brand et al. 2013; Burke et al. 2003; Rubak et al. 2005), and professional development of culturally competent mental health practitioners (Brammer and MacDonald 2002; Carlson and Erickson 2001). These approaches all capitalize on individual or collective narratives as the basis for identifying goals for growth (development or remediation) and negotiating cognitive reconstruction or change in narratives in order to influence interpretation of experiences and behavioral responses.

Consistent across anthropological, psychological, and public health narrative approaches to practice and professional development2 is the process of cultural transformation through negotiation—construction, eliciting the client’s story related to psychological distress, patient’s illness narrative, or trainee’s personal narrative related to professional practice; deconstruction, critically analyzing the narrative and identifying factors contributing to health or practice problems which could be focus for change; and joint reconstruction of action-oriented stories or narratives that increase health promotion, risk reduction, or professional practice actions. This process takes place through interaction of two or more individuals, such as practitioner–patient or trainer–practitioner. The co-construction process inherent in the intentional interpersonal interaction, directed toward a particular goal, is the key to facilitating the telling of one’s story, cognitive script, or schema, and examining or deconstructing the story in relationship to the presenting problem or goal. Thus, the narrative provides basis for identifying the biological, affective, cognitive, behavioral, social, cultural, and structural factors related to the presenting physical illness, psychological distress, or goal of culturally competent professional practice. In addition, the existing narrative is the key to developing a new narrative to facilitate change through relief of symptoms or development of adaptive or health-promoting behaviors or culturally competent practice.

We developed the Narrative Intervention Model as a culturally constructed approach for use by medical practitioners to provide counseling to patients with gupt rog. The providers were trained to elicit the patient narrative and then extract the emotional, cognitive, behavioral, cultural, and contextual factors, which had been identified in formative research with the study population to be associated with STI/HIV risk. The provider then facilitated the critical analysis (deconstruction) of these elements, and used results of the analysis to enable the patient to reframe the narrative (reconstruction) in the form of strategies that capitalize on risk-reducing or risk-avoiding factors and thereby minimize risk-inducing factors. We used this approach in a six-year intervention study in low-income communities of Mumbai. Providers (allopathic and ISM practitioners) were trained to treat married men coming into clinical care for gupt rog, using the NIM.

The Narrative Intervention Model (NIM)

The NIM reflects the integration of psychological, anthropological, and public health perspectives in health risk prevention approaches in several ways. First, practitioners are trained to reflect on their own explanatory models, treatment process, and treatment options, and to engage with and address the situational constraints that could interfere with treatment enhancement in their resource-limited setting. They then learn skills to facilitate the construction, deconstruction, reconstruction process with their patients in an efficient and effective way. To implement the process, the practitioner first elicits the patient’s/client’s culturally embedded cognitive schemas or scripts through a narrative, and identifies the cultural, interpersonal, and psychological factors that influence risky behavior, treatment seeking, and/or service provision. Second, the practitioner selects those specific elements of the patient/client’s cognitive script known to influence health-promoting or risk-reducing behaviors. Third, the practitioner co-constructs with the client an alternative narrative that revises these reported behaviors and beliefs in accordance with their life situations, to shift from risk promotion to risk avoidance. Finally, the provider and client develop together a specific set of guidelines that the client can use to guide decisions related to HIV risk in the future.

Central to the NIM is the cultural constructions and meanings of illnesses specific to patients and providers. In addition, the NIM represents a holistic or comprehensive perspective that considers the biological, psychological, sociocultural, and political dimensions of illness or health risk, such as risky lifestyle, gender roles and discrimination, and power relations. The construction of the NIM process thus reflects an interpretive perspective based on the narratives of patients and medical practitioners gathered during formative ethnographic research phases of our work.

In the application of NIM, practitioners construct individualized narratives with their patients as part of history taking (constructing the narrative). The proposed elements for guiding narrative construction, derived from formative research with the study population, included: presenting symptoms, perceived etiology, perceived consequences, treatment seeking, lifestyle indicative of risky behavior, marital relationships, and perceptions of masculinity. Using the constructed narrative, practitioners and patients together critically examine the biological, psychological, relational, social-cultural, political, and economic factors that influence or maintain the reported problem and may contribute to risk for future health problems (deconstructing the narrative). Although the proposed elements guide the construction of the narrative, the importance of specific elements (e.g., perceptions of masculinity) is expected to vary across patients, and additional factors (e.g., family relationships) could be identified. This deconstruction process serves to externalize the health concern for systematic examination and articulation of cultural meanings, explanatory models, and illness narratives of both patient and practitioner. The conduct of the NIM supports the co-construction of new cultural meanings, explanatory models, and illness narratives acceptable to both practitioners and patients, that suggest pathways for behavior changes and illness management (reconstructing the narrative). Furthermore, the construction-deconstruction-reconstruction (reflection/behavioral direction) process can allow for integration of different conceptual models or systems of health care deemed acceptable by both providers and patients. These narratives also assist the practitioner in developing cultural formulations (via narratives that are situated in larger cultural narratives) that guide subsequent diagnosis and decisions about medical treatment and preventive intervention (i.e., health education and risk reduction), thus influencing professional development.

The NIM Intervention in the Study Communities

The study communities are located in a fringe area of Mumbai, populated since the late 1970s by people from central Mumbai and migrants from across India. These communities, with an estimated total population of 700,000, were designated as slums because they are situated on land owned by public and private sectors which can be claimed at any time and include a large number of illegal or unauthorized structures. Most (66 %) community members were migrants, split between Hindu and Muslim religious affiliation (total of 96 %). Most households (81.3 %) consisted of one room, accommodating nuclear (47 %) or joint and extended families (37.1 %) averaging 6.4 individuals. Most men were employed (only 1.5 % report unemployment) as daily wage workers (39.8 %) or petty traders and business owners (27.5 %), and earned a mean monthly income of Rs. 3272 (US$65). Only 4 % of wives generated cash income (mean of Rs. 1,353/month; US$27), with 40.6 % of working in embroidery at home. (See Schensul et al. 2009a, b for further detail.)

Ethnographic Research Informs the Local Narrative Intervention Model for Clinical Practice

Formulating a culturally constructed intervention approach necessitated consideration of the ‘culture’ (collective meanings, knowledge, actions) of participating communities and, in this case, the explanatory models of sexual health problems both for practitioners and patients. Ethnography provides methods for understanding culture at both collective and individual levels, for operationalizing explanatory models of patients and practitioners (Csordas et al. 2010; Kleinman 1992; Kleinman and Benson 2006), and for developing culturally constructed approaches to health care, health risk prevention, and health promotion (LeCompte and Schensul 2010; Nastasi et al. 2004; Schensul et al. 2004; Verma and Schensul 2004). In our work, ethnography was the major methodological tool for formative research to inform the development of a local narrative intervention model.

The populations were married men living in urban Indian slum communities and practitioners of allopathic and Indian Systems of Medicine (ISM) practicing in these communities. Allopathic (biomedical) services were available primarily through government-run urban health centers or health posts under the auspices of the Mumbai Municipal Corporation, with staffing by faculty, residents, and students from a Mumbai-based medical college. The government health care system in urban slum communities is primarily equipped to address the needs of pregnant women and children. These centers do not typically address men’s sexual health concerns including sexually transmitted infections, STIs.

Most (90 %) private medical practitioners practiced ISM, also referred to under the umbrella of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga [and Naturopathy], Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy; Schensul et al. 2006a, b, c). ISM practitioners dominate care in the low-income communities of Mumbai. In contrast to the allopathic focus on diagnosis and treatment of symptoms, traditional ISM/AYUSH practitioners adopt a holistic approach focused on the patient’s overall well-being, consistent with the NIM. Our formative research, however, indicated that actual AYUSH practice in urban poor communities of Mumbai more closely resembled an allopathic symptom-focused approach; 80 % of AYUSH practitioners reported a primary focus on symptoms and prescribing of allopathic medicine (antibiotics; Schensul et al. 2006a). In addition, the brief duration of the diagnostic phase of a clinic visit, typically 5–15 min, provided minimal time to gather information about personal, interpersonal, or cultural factors related to sexual health problems. The AYUSH providers attributed the modifications of traditional holistic practice to the high volume of patients and the need for quick turnaround to generate sufficient income in urban poor communities. One of the challenges in developing a model for clinical practice in India was to ensure that the model (a) encompassed both Indian allopathic and ISM models, (b) provided a more holistic approach to clinical practice consistent with traditional ISM, and (c) could respect time constraints through implementation as a brief intervention.

Formative ethnography was focused on understanding doctor and patient explanatory models of sexual health problems. To understand the perspective of practitioners, we examined the theoretical foundations of Indian medical systems and their respective applications to the diagnosis and treatment of gupt rog, as reflected in professional texts and training approaches (e.g., at medical training institutions) as well as the voices of practitioners in the participating communities. To understand the perspective of actual and potential patients, we conducted in-depth interviews and structured surveys with married men in the target communities. These interviews and surveys focused on sexual health concerns (gupt rog) and individual psychological and social-cultural factors that related to sexual risk in the context of life in poorly resourced low-income urban Indian communities. The interviews were structured to elicit narratives from men and providers related to men’s sexual health concerns, and to identify factors that might be contributing to sexual health risks. The surveys provided quantitative data on the range of variables derived from the interviews in order to test the proposed relationships between contributing factors and sexual health problems. In the next section, we summarize the key domains based on collective schema of practitioners and married men.3

Identifying Key Domains

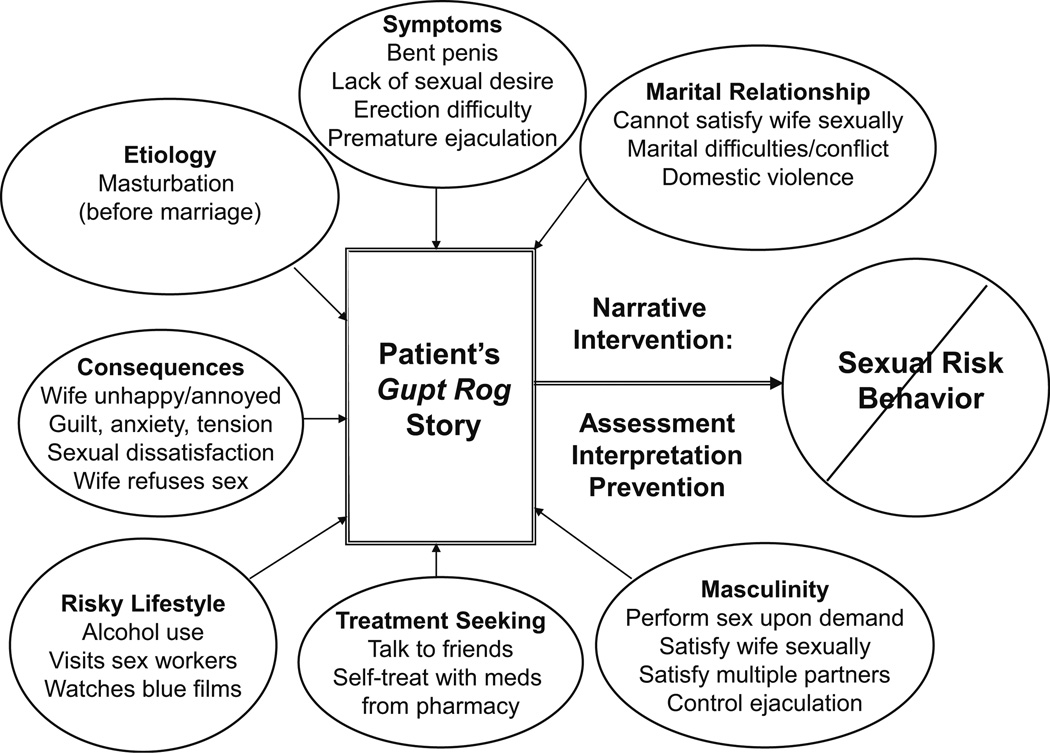

The key domains relevant to constructing illness narratives were symptoms, perceived etiology and consequences, treatment seeking, masculinity, marital relationships, and lifestyle risks such as alcohol use, extramarital sex, and intimate partner violence. Our formative research, using in-depth ethnographic interviews, provided the basis for identifying and defining the variables within each domain from the perspectives of patients, practitioners, and community members (prospective patients) and for articulating the gupt rog narratives of men and practitioners, and developing the relevant NIM. Following are the definitions of seven key domains as defined collectively by married men and practitioners, and depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Case Illustration of NIM for Gupt Rog. This figure depicts the NIM process in which the patient’s story guides assessment (construction), analysis and interpretation (deconstruction), and prevention and treatment (reconstruction). The goal of the narrative intervention for gupt rog is to reduce or prevent sexual risk related to STIs/HIV for married men in low-income communities of India. The patient’s gupt rog narrative, constructed with the medical practitioner, includes information about factors related to symptoms, perceived etiology, actual or expected consequences, previous treatment seeking, sense of masculinity, marital relationship, and risky lifestyle. This depiction includes information from the case illustration described in detail in the text

Presenting symptoms such as early ejaculation, semen loss related to masturbation or nocturnal emission, erectile dysfunction, weakness, pus discharge, blisters on the genitals

Perceived etiology of the problem, for example, excessive masturbation, frequent semen night falls (nocturnal emission), sex with commercial sex worker, sex with elder women

Perceived consequences of the reported problem such as marital discord, anxiety about sexual perform within marriage, or emotional distress

Treatment-seeking behaviors, including self-treatment with various ayurvedic (ISM) and allopathic medications (e.g., antibiotics), and seeking treatment from multiple practitioners and multiple medications

Lifestyle indicative of risky behavior, for example, alcohol abuse, smoking, watching pornography (blue films), visiting commercial sex workers (CSWs), and extramarital sex

Marital relationships, including spousal communication, sharing of roles and responsibilities, domestic violence, and sexual relationship (including sexual violence, sexual satisfaction)

Perceptions of masculinity, for example, the importance of sexual performance to sense of masculinity

We used the formative interview data to construct our definitions of key domains and variables, to understand the narratives of men and providers regarding how these domains related to gupt rog, and to develop ethnographic surveys (i.e., informed by the ethnographic data) to gather population-level data. Analyses of the survey data established correlations between the key variables to gupt rog, and between gupt rog and sexual risk (STIs/HIV) for married men (as depicted in Fig. 2). The analysis of survey data confirmed our understanding of sexual health derived from men’s and providers’ narratives during interviews. Based on these findings, we designated gupt rog as the marker for recruitment of men into HIV/STI risk reduction interventions via local public or private medical facilities (Schensul et al. 2007, 2009a, b).

Understanding Gupt Rog Narratives

Particularly important to the development of the NIM was the culturally based beliefs among both men and practitioners which may have linkages to increased risk for HIV/STIs, as depicted in their narratives about gupt rog (e.g., Fig. 2). For example, men expressed the belief that semen loss through masturbation contributed to physical and psychological weakness (e.g., current symptoms) and thus was to be avoided, but such concerns did not extend to semen loss through sexual intercourse. Similar beliefs were evident among practitioners, some of which reflected assumptions of traditional systems of medicine (e.g., the importance of bodily fluids such as semen to overall well-being). Narratives of both practitioners and men suggested that treatment by both allopathic and AYUSH practitioners focused on assessment and diagnosis based on symptoms coupled with pharmaceutical treatment with ‘English’ (allopathic) medicine (e.g., antibiotics). In some cases, doctors indicated that they questioned men about lifestyle factors, but this was typically restricted to questioning about exposure to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) through sex with high-risk partners (e.g., commercial sex workers). Similarly, both allopathic and AYUSH doctors reported ‘counseling’ patients by ‘scolding’ and ‘cautioning’, though not necessarily educating, about extramarital sex with commercial sex workers. Doctors’ narratives from formative research data indicated that they infrequently addressed psychological, relational, or social-cultural factors. Such findings highlighted the importance of addressing the norms of both doctors and their patients in order to influence clinical practice and risky sexual practices, respectively. Moreover, the narratives that guided our NIM development were based on collective representations by doctors and actual or potential male patients. As with any population, there also were variations in the narratives across individual doctors and men. In addition, the narratives did not always reflect practice consistent with established medical systems. Thus, our goal in developing NIM was to capitalize on shared perspectives but consider how to address variations across patients and providers in NIM application and to include in provider training a review of current best practices for treatment and prevention of STIs/HIV.

Applying NIM to Treatment and Risk Reduction of Men’s Sexual Health Concerns

The primary objective of the men’s project was to facilitate the application of the NIM to clinical practice of allopathic and ISM doctors in the context of their treatment of men presenting with the various types of gupt rog, specifically, sexual performance difficulties, semen-related concerns, and STI-related symptoms. Using the NIM process depicted in Fig. 2, we implemented a training program for allopathic practitioners working in a male health clinic established by the project partners and AYUSH practitioners working in private clinics within the target communities. Over a 2 ½-year period, participating doctors were asked to apply NIM to all cases presenting with gupt rog symptoms. In addition, the project team provided ongoing consultation and follow-up trainings throughout this period to ensure effective implementation of NIM. For the purposes of research, data collection was conducted with a random sample of patients presenting gupt rog symptoms to the participating practitioners. Data collection focused on acceptability, integrity, and outcomes as reported by patients (see Saggurti et al. 2013). In addition, practitioners were interviewed mid-term and at the end of the project to assess their understanding and implementation of NIM to selected cases. In this section, we briefly describe the training of practitioners and the adaptation of NIM to individual patients. We conclude with a case illustration.

Provider training consisted of an initial 16-h program conducted over 4 days and nine follow-up group training sessions (1–2 h duration) across the project period. The follow-up sessions were based on doctor’s requests for extended or refresher training on topics such as sexual dysfunctions and application/adaptation of NIM to actual cases. Training activities included lectures, practice exercises, and role playing of cases. At the conclusion of the men’s project, a manual was developed to assist in subsequent training of practitioners across India (Nastasi et al. 2007). The content of provider training (and the manual) included background on RISHTA, formative research findings, theoretical foundation of NIM, basic counseling and communication skills, record keeping, medical history taking, symptoms and treatment of various STIs, HIV/STI counseling, syndromic management of STIs based on prevailing WHO (1993) guidelines, and NIM application to illustrative cases. Both the allopathic practitioners in the public health clinic and the AYUSH practitioners based in private clinics in the study communities participated in the training sessions together, thus ensuring they received the same content and benefitted through an exchange of perspectives.

Although the NIM provides a structure and process for guiding patient care, effective application requires adaptation to the individual symptoms, knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of each patient. Thus, the NIM is not a scripted approach but a guided process for engaging in assessment of patient concerns and lifestyle (construction); interpreting the information and identifying target areas for treatment and prevention (deconstruction); and delivering treatment using syndromic management and psycho-education and counseling to facilitate changes in knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors (reconstruction). Although the practitioners were advised to collect information about all of the domains depicted in Fig. 2, the subsequent treatment and prevention efforts focused only on those areas that were deemed relevant to the specific patient’s gupt rog symptoms and risky sexual behavior. Working with the practitioners in Mumbai slums taught us the importance of articulating the NIM to reflect the language and process of standard medical treatment. Thus, we conceptualized the three steps of NIM, construction, deconstruction, reconstruction, as an extension of the existing practice of history taking, diagnosis, and treatment, respectively. In addition to considering symptoms, practitioners were asked to include patient’s perceptions of causes and consequences of symptoms, treatment-seeking efforts, beliefs about masculinity, marital relationship, and risky lifestyle. Moreover, in addition to treatment of symptoms, practitioners were asked to conduct preventive intervention to address contributing psychological, relational, and cultural factors.

NIM Protocol

To facilitate implementation, we developed a protocol with guiding questions for the three steps of NIM, and provided a patient case sheet to practitioners that included sections for both medical and personal lifestyle factors (etiology, marriage, risky behavior, etc.), diagnosis/case interpretation, and treatment/prevention actions. The record sheets provided a mechanism to monitor and assess adherence to NIM. In this section, we detail the 3-step protocol, with guiding questions for practitioners, and then present an illustrative case study of patient-provider engagement in NIM (depicted in Fig. 2).

Step 1. Construction (Assessment/History Taking)

The first step of the NIM process is a comprehensive and expanded history taking, to assess medical, psychological, social-cultural, and relational domains—the development of the patient’s gupt rog narrative/story (see Fig. 2). In addition to the construction of the patient’s story, the doctor performs medical examinations and lab tests deemed appropriate. To facilitate narrative construction, we provided guiding questions (e.g., see provider questions in case example).

Step 2. Deconstruction (Diagnosis and Interpretation)

The purpose of the second step is to analyze the patient’s story and identify the factors related to patient’s gupt rog or sexual risk behaviors. The identified factors then become the focus for treatment and prevention in the next step. Critical to this step is the doctor’s thorough consideration and analysis of all the information gathered from the narrative (e.g., as depicted in Fig. 2) and determination, in discussion with patients, of what requires subsequent action. Practitioners were encouraged to use a reflective process for deconstruction, asking themselves for example, “Which factors are important to treating and preventing this patient’s gupt rog?” They were encouraged to review the information they recorded in the case record (and using graphic displays such as Fig. 2) to develop a picture (depiction) of the patient’s gupt rog. To facilitate the analysis and interpretation process, we provided a set of self-guiding questions (such as that above and as illustrated in case example). Deconstruction also involved communicating the diagnosis and contributing factors to the patient and interpreting the gupt rog story in patient’s language to ensure understanding. For example, practitioners were encouraged to consider how to best explain the factors that contributed to the current problem (e.g., premature ejaculation) and future sexual risk (e.g., STIs for self and partner). This intent of the analysis was to facilitate the individualization of the NIM, so that the practitioner gave attention to the current gupt rog and potential contributing factors deemed relevant to this patient’s illness and risk.

Step 3. Reconstruction (Treatment and Prevention)

The third step is focused on helping the patient to create a new narrative to support health-promoting and risk-reducing beliefs, behaviors, relationships, and experiences. Consistent with prevailing guidelines for syndromic management (WHO 1993), this step involved relevant medical treatment, partner notification, referral, HIV/STI counseling, and providing information about specific prevention strategies, including condom promotion. This step also addresses the factors identified in the preceding step as relevant to current and future sexual risks, thus expanding standard medical treatment and creating the new health-promoting narrative. From among all the possible contributing factors, the doctor focuses on those relevant to the specific patient. In order to facilitate the process in this step, we provided a set of self-guiding questions for planning and delivering treatment and prevention education, which could include syndomic treatment for STIs, challenging myths (e.g., masturbation causes erectile dysfunction), educating patients about risky sexual practices (e.g., unprotected sex with sex workers), explaining how psychological and interpersonal factors (e.g., anxiety, marital discord, lack of communication) might contribute to sexual health concerns, and generating strategies for behavior changes (e.g., how to communicate with spouse about sex, protection against STIs). Practitioners also were encouraged to make appropriate referrals for further services (lab testing, treatment, STI counseling, etc.) and were provided with a list of resources in the community.

Case Illustration

The sample case depicts the application of NIM to doctor–patient interaction regarding a patient’s gupt rog. This case represents an amalgamation (rather than a single case, to protect patient identity), drawn from actual narratives of patients and providers. The content of the case (the patient narrative) is depicted in Fig. 2. The following is structured to reflect the 3-step construction-deconstruction-reconstruction process.

The interaction that follows is between an ISM provider and married male patient, age 25, who presented with gupt rog symptoms, characterized by bent penis, premature ejaculation, erection difficulties, and loss of sexual desire. Prior to this visit, the patient had attempted to self-treat using medication obtained from a local pharmacy, per the advice of friends.

Step 1. Construction

The doctor–patient interaction was designed to create the patient’s narrative of gupt rog. The doctor’s questions are based on those provided in the manual and taught in training. The respective domain is indicated in brackets; the content of patient’s responses is reflected in Fig. 2.

[Symptoms]

Doctor: “Tell me about the problem(s) you are currently having.”

Patient: “I am suffering from the problem of bent penis, lack of desire for sex, erection difficulty, and early ejaculation.”

[Etiology]

Doctor: “What do you think first caused the problem?”

Patient: “Before marriage I used to masturbate… by which I wasted semen to a great extent, for which I suffered the problem of bent penis, lack of desire for sex, erection problem and early ejaculation… .Those who do excessive masturbation, their semen bag becomes weak and [are not able to do] intercourse…there is no semen in the penis, how can I get erection?… In this case, [men] should not marry.”

[Consequences]

Doctor: “How have the symptoms affected your life?”

Patient: “My wife wants sex for a longer period, but unfortunately I get early ejaculation… if my wife is not satisfied, she will get attracted to other males.” [when asked to say more about wife’s reaction]… “she becomes annoyed and teases me for this [or] she sleeps with anger and doesn’t talk to me….When I get early ejaculation… she says, if you don’t know how to do, then why you are doing, then I feel guilty for this…then I get scared to have sex with her. Due to anxiety and hesitation, I ejaculate beforehand.”

[Treatment seeking]

Doctor: “What have you done to relieve the symptoms?”

Patient: “I got English medicine from pharmacy…my friend told me he used it…I talk to my friends [about these problems]…”

[Risky lifestyle]

Doctor: “Do you do any of the following activities alone or with your male friends: Drinking? Using other drugs? Visiting commercial sex workers? Having sex with beer bar girls (waitresses at beer drinking establishments) or other female partners? Watching blue films (pornographic films)?”

Patient: “I drink with my friends at beer bars and sometimes we visit the CSWs (commercial sex workers)…they [CSWs] are prepared to do sex in different ways, as we saw in blue films [pornographic films]…I can enjoy as I wish..and feel like a real man…within Rs 50/[about US$1].”

[Masculinity]

Doctor: “What does it mean to be a ‘real man’?

Patient: “A real man or manliness is [one] who can satisfy his wife and should be ready for sex whenever his wife asks for sex. If he has relation with more than one woman, he should be able to [satisfy] all…he should be able to control himself till her ejaculation.”

[Marital relationship]

Doctor: “Tell me about your relationship with your wife.”

Patient: “From a health point of view, there should not be any sexual health problems. So he [husband] will be able to satisfy the sexual urges of his wife and in turn marital relations will be good…but my wife now completely refuses for intercourse… I shared the experience with my friends… they told me nothing is wrong in this, every woman searches for some excuses to avoid sex.”

Doctor: “What else can you tell me about your relationship with your wife?”

Patient: “So always my wife fights with me for the luxurious amenities, which I can’t provide her. Once I became very upset and slapped her…. Sometimes, due to alcohol, I beat her.. .Last night I drank a bit, when I went near her she said I am stinking, so I should stay away. Then I got angry and slapped her.”

Step 2. Deconstruction

The following is the doctor’s description of the analysis of the patient narrative. The doctors were encouraged to do this analysis in preparation for discussion with the patient, using the case record or constructing a graphic similar to Fig. 2, as they collected the narrative. This reflective description is based on data from follow-up interview with provider and written case record. The guiding questions (from the NIM manual) are indicated in brackets.

[What is the gupt rog problem?]

Main problem is sexual performance and tension. He is suffering from gupt rog due to performance problems (premature ejaculation, erection difficulty) which is also affecting sexual desire and satisfaction. He was very much scared that due to this problem, his wife will quit him some day and he will have to face societal disgrace. He was quite tensed when he came to meet me. I would say in India misconception relating to sex is the major problem. There is very little communication between husband and wife regarding sexual matters, which leads to further complications. Also, in India misconception about masturbation is problem as many think it can lead to sexual and physical weakness. Also, his problem is causing him tension which only makes it worse…. I examined his genital area but there was no structural problem. Even he reported to get normal erection in the morning. Undergoing laboratory tests were not required for him.

[Which factors are important for understanding and treating this patient’s gupt rog

Etiology—masturbation—misconception about consequences of masturbation, current problems are not result of masturbation

Consequences—dissatisfaction in sexual relationship with wife, anxiety about wife’s reactions, tension and anxiety about sexual performance

Treatment seeking—medication from pharmacist based on friend’s advice

Risk lifestyle—drinking, blue films, extramarital sex with CSWs—creating atmosphere for sexual risks (STIs, HIV/AIDS), drinking contributing to domestic violence, blue films present unrealistic sexual expectations

Masculinity—misperceptions about sexual prowess as major factor in masculinity—leads to further distress about sexual performance problems, unrealistic expectations for self

Marital relationship—dissatisfaction, conflict, violence—cycle of factors are likely consequences of and contributors to sexual difficulties

Step 2/3. Deconstruction/Reconstruction

The following doctor–patient interaction illustrates the doctor’s explanation of contributing factors (deconstruction) and efforts to help the patient to develop an alternative narrative to address the presenting concern and contributing factors, and reduce future sexual risk (reconstruction). As such, this interaction reflects how the doctor integrates deconstruction and reconstruction in the dyadic interaction (based on the doctor’s analysis depicted above). The bracketed information indicates the target domain(s), as depicted in Fig. 2. In the course of the deconstruction and reconstruction narrative, the doctor combines an ethnographic approach, using guiding questions to explore the patient’s perspective and help the patient to identify factors relevant to his concerns, with education about sexual risks and suggestions for prevention and risk reduction. In addition, the doctor links the different factors in his deconstruction of the case (e.g., marital relationship, masculinity, and presenting concerns).

[Symptoms/Etiology/Consequences]

Doctor: “Masturbation does not cause the problems you are having.”

Patient: “But what is cause?”

Doctor: “What may have started as typical problem (early ejaculation and difficulty with erection-can happen for all men) has become big problem. You say you are now scared due to this problem when you engage in intercourse and you are scared that your wife will quit you some day and then you will face disgrace. I understand that you are tensed about this but that is making problem worse. And your wife has become annoyed which can also increase your tension.”

Patient: “Yes, my wife has become annoyed and refuses intercourse. My friends say women just make excuses.”

Doctor: “I understand.”

Patient: “I get angry with her and now she always fights with me. And she complains that I cannot provide for her the luxurious amenities or sexual satisfaction. Sometimes I get so annoyed I slap her especially if I drink a lot.”

[Masculinity]

Doctor: “You say that a ‘real man’ should always be ready for sex and is one who can always satisfy his wife. But this is not so. Of course, you want to be able to satisfy your wife and have a happy marital relationship. But a real man is much more than that…. a real man also loves his wife and children, provides a home and food for his family, helps others in the family and neighborhood…. and you say that you do all of that.”

Patient: “OK, but what do I do about my problems?”

[Symptoms]

Doctor: “What do you do after going to bed?”

Patient: “We immediately start to do the intercourse.”

Doctor: “Don’t do the intercourse immediately…. Before intercourse at least 20–30 min you spend on foreplay with her.

Patient: “Yes, I can try that.”

[Risky lifestyle/Sexual risk]

Doctor: “You say you drink with friends. How often do you go with friends?”

Patient: “About once a week. We go to beer bar, drink and then see blue films. Sometimes we visit CSWs as they will do what we see in blue films and I get enjoyment.”

Doctor: “What you are doing with your friends can affect your health and marriage. You say that when you drink a lot, you sometimes hit your wife. This cannot be good for your relationship with her…. Also, are you aware of the risks of disease when having sex with CSWs?”

Patient: “My friends say the ones we go to are safe. So I am not worried. We have not gotten sick.”

Doctor: “Yes, but there are risks when having sex with women who have several partners. You cannot be sure you will not catch a disease, an STI. And if you get STI, it can increase risk for HIV/AIDS which could be fatal for you and your wife and unborn children.”

Patient: “Yes…but what can I do?”

Doctor: “You should avoid such casual sex. If your friends are forcing you, you should avoid going with them. However, if you do sex with CSW, then you must use condom.”

[Sexual risk/Risky lifestyle]

Patient: “I understand but we have never gotten sick. Should I be worried?”

Doctor: “Yes, not only can you get an STI or HIV/AIDS but you could infect your wife. I suggest we do tests to make sure you do not have one of these diseases.”

Patient: “But how much does that cost?”

Doctor: “We can provide free for you and for your wife if needed.”

[Marital relationship]

Doctor: “If you and your wife are happy with your sexual relationship, then it could help with the other problems in your marriage…. I suggest you share your concerns with your wife—tell her about your visit with me and what [we discussed]…. And if you get angry and want to slap her, it is better to go outside until you calm down. Then you can try to talk about what is concerning you both.”

Patient: “You think so? I can try that.”

Doctor: “If you want to bring your wife in, I would gladly talk with you both about how to address your gupt rog problems together and how to improve your marital relationship—how to talk to each other about your concerns.”

Patient: “Yes, I can ask her. I think that would be helpful. I know my wife would like if we were happier and had better sexual relationship.”

The doctor and the patient have explored a number of contributing factors to the sexual health concern, with the expectation that the patient would further reflect on the issues raised and consider the suggestions for making changes. Follow-up sessions would focus on assessing the changes in patient thinking, behavior, and sexual health concerns (i.e., whether the patient has created new narrative), and further guiding the patient in developing a healthy narrative. The session ends with agreement for a session with both husband and wife to explore ways to improve the marital relationship and address sexual concerns as a couple. Although couples’ sessions were not part of the standard protocol, some of the doctors offered these sessions as an extension of the NIM with men.

Applying NIM to Practice

Effective implementation of NIM within providers’ day-to-day practice required an ongoing process of monitoring for integrity and acceptability, practitioner support and training, and decision making about modifications for individual practitioner–client dyads. In this section, we discuss key considerations that warranted continual attention throughout project implementation and can inform translation to other settings.

Individualizing to Patient–Practitioner Dyads

The utility of any approach to clinical practice is dependent in part on the flexibility for individualization across practitioners and clients. Developing a model that was adaptable to both allopathic and AYUSH practitioners required thorough understanding of the variations in these systems of medicine, accomplished through our formative ethnographic research, and involvement of practitioners in refinement of the NIM to ensure applicability to both allopathic and AYUSH approaches, accomplished through training and feedback throughout the project period.

Individualizing the NIM across clients was accomplished via the narrative process. We conceptualized the construction step as the mechanism for gathering a mini-ethnography from each client, consistent with Kleinman’s (1992; Kleinman and Benson 2006) explanatory model and Lo’s (2010) cultural brokerage model. Effective adaptations across patients required specific training for the practitioners. The narrative construction (i.e., expanded assessment) posed minimal challenges as this process was guided by a set of questions and the conceptual framework. More challenging were the processes of deconstruction, identifying contributing factors, and making decisions about how to proceed, and reconstruction, employing cognitive-behavioral strategies to facilitate a new health-promoting narrative (schema) and related behaviors. The development of practitioner skills related to deconstruction and reconstruction required that the project staff provide consultation and opportunities for practice through guided role play.

Addressing Logistics

Practitioners found that effective use of NIM required extending clinic visits to 20–40 min duration across 1–3 sessions (Saggurti et al. 2013). As noted previously, this exceeded the typical one session of 5–15 min duration. Although doctors were not opposed in principle to extended sessions and patients responded positively to the broader focus on NIM, the volume of cases and additional costs incurred by patients posed challenges to implementation. Multiple sessions were more feasible in the urban health center where government subsidies helped to minimize client fees.4 In urban health care setting, practitioners reported that men were likely to seek multiple sessions but the volume of cases forced them to limit the number of sessions for each client. In contrast, the private providers could more easily provide extended sessions, but the additional cost to clients was prohibitive. Nevertheless, the practitioners reported that men were interested in and sought continued ‘counseling’ about factors that contributed to sexual risk. Moreover, as noted earlier, practitioners reported extending the use of NIM in treatment of other health problems within their general practice. For example, they collected more in-depth case histories that included information about contributing social-cultural and psychological factors; they viewed their cases in more holistic manner, and provided education and counseling about lifestyle factors contributing to health problems. Thus, even with the practical problems, we were successful in implementing a brief intervention of a duration that is consistent with recommendations from other health risk reduction studies (e.g., alcohol use reduction; Kari 1999).

Finally, a potential challenge in public health approaches to sexual risk reduction for men is the lack of government-funded health centers that serve the needs of men. Working in partnership with a local medical school, we established a ‘male health clinic’ with timings and days that did not overlap with women’s clinics and were convenient for working men. In addition, community education campaigns were instituted to raise awareness about sexual risk and availability of services in the public sector. The clinic was still functioning in the urban health center 6 years after project completion. Furthermore, the urban health center collaborated in developing a women’s health clinic focused on reproductive and sexual health concerns which served as the site for a subsequent project (2007–2013) to apply NIM to STI/HIV prevention with married women and couples.

Translating NIM

Consistent with the underlying philosophy of our work, the specific interventions we developed using NIM are not intended to be generalized to other settings or populations without consideration of the local culturally constructed narratives. The intent of our work was to develop and test a culturally constructed and adaptable evidence-based approach to sexual risk reduction for married men and women in low-income urban Indian communities. This article is intended to illustrate a transdisciplinary and participatory research-informed approach to developing culturally constructed interventions, through partnerships involving medical and social scientists, practitioners/interventionists, patients/clients, and community members. Using a transdisciplinary theoretical model, guided by the integration of anthropology, psychology and public health (Fig. 1), we conducted formative research to construct a culturally specific and locally situated clinical practice model (Fig. 2) for treating sexual health concerns of married men in urban health care clinics. To facilitate adaptability across practitioner–patient dyads, we incorporated a cultural construction process that was consistent with Lo’s (2010) cultural brokerage model and Kleinman’s (1988a) explanatory model. Using a process of construction-deconstruction-reconstruction, the practitioner negotiates a shared narrative with the client in order to facilitate cognitive or schema change toward health-promoting thinking and behavior. Our research supports the use of NIM in urban clinical practice in India with both allopathic and AYUSH doctors. Patients receiving treatment for gupt rog from providers trained in NIM reported receiving treatment and intervention consistent with the components of NIM (i.e., assessing psychological and social-cultural factors, providing psycho-education) and reduction in gupt rog symptoms and related behaviors such as extramarital sex (see Saggurti et al. 2013 for full details).

The extent to which existing evidence can inform subsequent translation and adaptation depends on factors such as the similarity of cultural context and phenomenon of interest, the success of the initial work, and quality of the evaluation research. In our own work, the subsequent translation of NIM from married men to married women and couples was facilitated by the comparability in community and medical culture, but required attention to psychological and social-cultural factors specific to women and to the married couple as a unit. Moreover, the health care systems overlapped and, rather than starting anew, we instead expanded our ethnography of urban health care to include both men and women’s sexual/ reproductive health concerns. Nevertheless, translation/adaptation required engaging new stakeholders in a cultural construction process and conducting additional formative research. The recycling through the research and development process helped to ensure that the adapted intervention is culturally and contextually relevant and addresses the appropriate phenomena (e.g., contributing factors).

Our intention in this article was to demonstrate a process for developing culturally constructed and adaptable interventions, using a transdisciplinary approach, in order to address the question: How do we develop evidence-based models to guide clinical practice that are sensitive to local culture and context? What is most critical for future work is replication of the process of model development, which we characterize as research-practice integration (see Table 1). Particularly important in the work of the RISHTA team was the use of mixed-method research as part of a recursive research ↔ intervention (praxis) process (Nastasi et al. 2007). Also critical was the interdisciplinary nature of the research and intervention team and stakeholder participation.

Table 1.

The recursive research ↔ intervention process for developing and translating the culturally constructed narrative intervention model (NIM)

|

Our work focused on the use of NIM as a specific intervention model for addressing sexual risk among married men (and subsequently women and couples) in clinical and community settings. Evidence from our early work supports its effectiveness with men (results for application to women and couples are forthcoming). The NIM, as tested in low-income urban communities of Mumbai, has potential for translation to other low-income urban communities in India and could be considered for adaptation to other types of communities as well. The translation of our specific NIM process outside of low-income urban communities in India depends on comparability of context and population. Additional formative research is necessary to inform broader application. More importantly, our work demonstrates that a recursive integration of research and intervention can help to address shortcomings of current evidence-based approaches, which often fail to address the potential diversity of cultural constructions across populations and contexts.

Footnotes

The research and intervention program known as RISRTA (meaning ‘relationship’ in Hindi/Urdu and an acronym for Research and Intervention on Sexual Health: Theory to Action), has included three NIH-funded projects, spanning 12 years (2001-2013): (a) Men’s Sexual Concerns and Prevention of HIV/STI (R01MH64875; PI, S. Schensul; Co-PIs, B. Nastasi, R. Verma, 2001-2007); (b) supplement, Assessing Women’s Risk of HIV/STI Transmission within Marriage in India, funded by the US Office of AIDS Research of NIH (2002-2006); and (c) Prevention of HIV/STI among Married Women in Urban India (PI, S.Schensul, Co-PIs, R.Verma, B. Nastasi, N.Saggurti, S.Maitra, RAras, A. Pandey, J.Schensul, 1R01 MH075678, 2007-2013). This manuscript focuses on our work in the initial project focused on men.

We bring professional development into our discussion as it relates to our training of medical practitioners within the context of our project; that is, implementing NIM for medical practice required reconstruction of providers’ schemas related to treatment of men’s sexual health concerns. We address this in a subsequent section related to program implementation.

A full articulation of these foundations can be found in the following publications: Kostick et al. 2010; Schensul et al. 2007; Schensul et al. 2006a, b, c; Schensul et al. 2009a, b; Schensul et al. 2004; Nastasi et al. 2007.

At the Urban Health Center, the fee for an initial visit was Rs. 10 (US $0.20) with no additional fees for follow-up visits within 15 days. Typical fees for private AYUSH providers were Rs. 30–40 (US $0.60–0.80) per visit.

Contributor Information

Bonnie Kaul Nastasi, Department of Psychology, Tulane University, 2007 Percival Stern Hall, 6400 Freret Street, New Orleans, LA 70130, USA, bnastasi@tulane.edu.

Jean J. Schensul, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, CT, USA

Stephen L. Schensul, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA

Abelwahed Mekki-Berrada, Universite Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada.

Pertti J. Pelto, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Shubhada Maitra, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India.

Ravi Verma, International Center for Research on Women, New Delhi, India.

Niranjan Saggurti, Population Council, New Delhi, India.

References

- Berger Peter L, Luckmann Thomas. The Social Construction of Reality: a Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bibeau Gilles, Corin Ellen. From Submission to the Text to Interpretive Violence. In: Bibeau Gilles, Corin Ellen., editors. Beyond Textuality. Asceticism and Violence in Anthropological Interpretation. Approaches to Semiotics Series. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 1995. pp. 3–54. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl Joao, Good Byron, Kleinman Arthur. Subjectivities: Ethnographic Investigations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl J, Petryna A, editors. When People Come First: Critical Studies in Global Health. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl J, Petryna A. Therapeutic Markets and the Judicialization of the Right to Health. In: Biehl J, Petryna, editors. When People Come First: Critical Studies in Global Health. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2013b. pp. 325–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. Le Sens Pratique. Paris: Éditions de Minuit; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Botella Luis, Herrero Olga. A Relational Constructivist Approach to Narrative Therapy. European Journal of Psychotherapy, Counseling and Health. 2000;3(3):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer Lawrence M, MacDonald Ginger. The Helping Relationship: Process and Skills. 8th Edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brand V, Bray K, Macneill S, Catley D, Williams KI. Impact of Single-Session Motivational Interviewing on Clinical Outcomes Following Periodontal Maintenance Therapy. International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(2):134–141. doi: 10.1111/idh.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimhall Andrew S, Gardner Brandt C, Henline Branden H. Enhancing Narrative Couple Therapy Process with Enactment Scaffolding. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2003;25(4):391–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner Urie. Environments in Developmental Perspective: Theoretical and Operational Models. In: Friedman Sarah L, Wachs Theodore D., editors. Measuring Environment Across the Life Span: Emerging Methods and Concepts. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The Efficacy of Motivational Interviewing: a Meta-analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials. [Meta-Analysis] Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Thomas D, Erickson Martin J. Honoring and Privileging Personal Experience and Knowledge: Ideas for a Narrative Therapy Approach to the Training and Supervision of New Therapists. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2001;23(2):199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas Thomas J, Dole Christopher, Tran Allen, Strickland Matthew, Storck Michael G. Ways of Asking, Ways of Telling: a Methodological Comparison of Ethnographic and Research Diagnostic Interviews. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010;34:29–55. doi: 10.1007/s11013-009-9160-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Veena, Das Ramendra K. How the Body Speaks: Illness and the Lifeworld Among the Urban Poor. In: Biehl Joao, Good Byron, Kleinman Arthur., editors. Subjectivities: Ethnographic Investigations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2007. pp. 66–97. [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta Sayantani, Meyer Dodi, Calero-Breckheimer Ayxa, Costley Alex W, Guillen Sobeira. Teaching Cultural Competency through Narrative Medicine: Intersections of Classroom and Community. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2006;18(91):14–17. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1801_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Samuel. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eron Joseph B, Lund Thomas W. Narrative Solutions in Brief Therapy. New York: Guilford; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher William A, Fisher Jeffrey D. A General Social Psychological Model for Changing AIDS Risk Behavior. In: Pryor John B, Reeder Glenn D., editors. The Social Psychology of HIV Infection. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen Dean L, Naoom Sandra F, Blase Karen A, Friedman Robert M, Wallace Frances. Implementation Research: a Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231); 2005. Electronic document, http://nirn.fmhi.usf.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines Atwood D. Millennial Medical Anthropology: From There to Here and Beyond, or the Problem of Global Health. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2011;35:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz Clifford. Observer l’lslam. Changements Religieux au Maroc et en Indonésie. Paris: Éditions de la Découverte; 1992–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz U. Cosmopolitans and Locals in World Culture. Theory Culture Society. 1990;7:237. [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham Colette L, Oka Evelyn R. Multicultural Issues in Evidence-Based Interventions. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2006;22(2):127–149. [Google Scholar]