Abstract

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are a widespread research tool because of their oxidation resistance, biocompatibility and stability. Chemical methods for AuNP synthesis often produce toxic residues that raise environmental concern. On the other hand, the biological synthesis of AuNPs in viable microorganisms and their cell-free extracts is an environmentally friendly and low-cost process. In general, fungi tolerate higher metal concentrations than bacteria and secrete abundant extracellular redox proteins to reduce soluble metal ions to their insoluble form and eventually to nanocrystals. Fungi harbour untapped biological diversity and may provide novel metal reductases for metal detoxification and bioreduction. A thorough understanding of the biosynthetic mechanism of AuNPs in fungi is needed to reduce the time of biosynthesis and to scale up the AuNP production process. In this review, we describe the known mechanisms for AuNP biosynthesis in viable fungi and fungal protein extracts and discuss the most suitable bioreactors for industrial AuNP biosynthesis.

Introduction

In recent years, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have gained importance as drug carriers, as their large bioavailable surface permit easy functionalization (Giljohann et al., 2010). AuNPs are not only resistant to chemical oxidation, but also stable in a wide range of environmental conditions (Shulka et al., 2005; Bhumkar et al., 2007; Gong and Mullins, 2009). AuNPs have applications in microbiology and medicine (Storhoff et al., 2004; Huang, 2007; Bhattacharya and Mukherjee, 2008; Jelveh and Chithrani, 2011), environmental sensing (Saha et al., 2012), and electronics (Huang et al., 2003). Examples of AuNP-based technology include biosensors to detect genetic material of bacterial origin (Pissuwan et al., 2010), photothermal therapy of tumours (Sperling et al., 2008), drug and gene delivery (Ghosh et al., 2008; Pissuwan et al., 2011) and catalytic removal of environmental pollutants (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2011b). Interestingly, AuNPs can be synthesized in a variety of shapes, from spheres (Wangoo et al., 2008) to rods (Dong and Zhou, 2007) to complex hexagonal crystals (Weng et al., 2008). AuNP shape and size determine most of their physical and chemical properties like plasmon resonance (Mock et al., 2002), antimicrobial activity (Wani and Ahmad, 2013) and catalysis rate (Zhou et al., 2010).

The physicochemical methods for the production of metallic nanoparticles in general and for AuNPs in particular rely either on a top-down or bottom-up approach. A summary of the main pros and cons of these methods is reported in Table 1. In the top-down approach, bulk metal is decomposed into nanoparticles using high laser ablation (Amoruso et al., 2014), pyrolysis or attrition (Thakkar et al., 2010). These techniques are generally deficient in controlling the nanoparticle size distribution (Mafuné et al., 2001) and in maintaining a quality surface structure for the physicochemical and catalytic properties of the AuNPs (Thakkar et al., 2010). The production of small AuNPs (diameter < 10 nm) with a more uniform particle size distribution is possible through optimization of the laser pulse time and process temperature (Amoruso et al., 2014). However, these techniques employ complex and hi-tech instrumentation facilities, thus involving a high cost production. In the bottom-up approach, AuNPs are constructed atom by atom starting from a precursor gold (Au) salt solution, using either ultrasound (Okitsu et al., 2007), radiation (Meyre et al., 2008), high temperature (Nakamoto et al., 2005), lithography (Wu et al., 2014) or chemical/electrochemical methods (Binupriya et al., 2010b; Samal et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013). Non-polar solvents used in chemical reduction synthesis methods have raised concerns for their environmental toxicity (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2010). On the other hand, physical methods usually require high temperatures and pressures, which makes it not only difficult to have control over AuNPs size and shape, but also increase energy consumption and production costs. Sol-gel synthesis facilitates the nucleation and growth process of AuNPs, yielding narrower size and shape distribution than those obtained with other physicochemical methods (Kawazu et al., 2004). However, sol-gel synthesis requires the use of toxic-capping agents like methyl methacrylate and butyl acrylate to prevent nanoparticle aggregation (Ye et al., 2011). Nanoparticles for biomedical application should be prepared only with biocompatible chemicals to minimize their toxic effect and increase their safe usage (Petrucci et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Pros and cons of physicochemical and biological methods for AuNP synthesis

| Method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Top-down synthesis | Highly controlled particle size distribution and shape. | Extreme conditions, high tech facilities, high cost. |

| Bottom-up synthesis | Cost-effective. Highly controlled particle size distribution and shape. | Potentially hazardous capping ligands and residual toxins add to environmental toxicity. |

| Bacteria | Cost-effective and environmentally safe. Biological capping agents for AuNPs stabilization. | Large nanoparticles with broad particle size distribution. It is not possible to obtain pure nanoparticles without any organic components. |

| Fungi | Cost-effective and environmentally safe. High concentration of extracellular redox enzymes and capping agents for AuNPs stabilization. Smaller size than bacterial-synthesized nanoparticles. Easy scale up. | Broad particle size distribution, low repeatability. It is not possible to obtain pure nanoparticles without any organic components. |

Green synthesis through microorganisms might overcome these toxicity issues. Microorganisms like bacteria, algae and fungi synthesize nanomaterials to benefit from their mechanical strength and chemical properties (Das et al., 2012a). For example, diatoms mineralize silica to build their cell walls (Frigeri et al., 2006), coccolithophore algae mineralize calcium carbonate to form calcite plates and build their exoskeleton (Young et al., 1999) and magnetotactic bacteria (e.g. Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense) synthesize magnetite nanoparticles (Schüler, 1999) to enable the bacteria migrate along a magnetic field towards low oxygen environments (Crookes-Goodson et al., 2008). Microorganism can synthesize metal nanoparticles through metal bioreduction to remove soluble metals from the surrounding environment, thus decreasing their toxicity and bioavailability. Microorganisms capable of metal bioreduction can colonize metal-contaminated environments. For example, Shewanella oneidensis can grow in presence of sub-mM concentration of Ag+ (Wang et al., 2010), Geobacter sulfurreducens can reduce in few hours soluble U6+ to insoluble U4+ (Orellana et al., 2013) and Fe3+-reducing mixed cultures can tolerate high concentration of Ni, Cu, Cd, Zn, and Co (Burkhardt et al., 2011). A combination of biosorption and bioreduction strategies enable Aspergillus sp. isolates from Cr deposits to tolerate up to 1 mM of Cr6+ in liquid medium at neutral pH (Fukuda et al., 2008). Bioreduction has therefore been extensively studied for its application in the bioremediation of metal-contaminated soil and groundwater. We would like to refer the reader to an excellent review in the area (Lovley, 2003). In microorganisms, extracellular bioreduction reactions might occur in the via microbially produced electron transfer agents (mediated electron transfer) such as the flavins secreted by Shewanella sp., which allows the bacteria to shuttle metabolically generated electrons to external electron acceptors (von Canstein et al., 2008) or membrane-associated cytochromes and redox proteins (direct electron transfer) (Mukherjee et al., 2002; Marshall et al., 2008).

The mechanism of metal bioreduction in bacteria, particularly dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria is now well understood and has contributed to the understanding of nanoparticles biosynthesis in these organisms.

Biosynthetic methods of AuNPs that are based on viable microorganisms or their protein extracts do possess two major benefits: they have a lower environmental impact and increase cost-effectiveness. This is because, for a very low cost, microorganisms produce in a renewable manner both the bioreduction and the capping/stabilizing agents needed in the process, without the need of exogenous chemicals. Furthermore, biosynthetic mechanisms might produce AuNPs of the desired shape, size and distribution given the highly specific interactions of the biomolecular templates and inorganic materials (Cölfen, 2010; Das et al., 2012a). The ability to manipulate the shape and size of AuNPs might enable their rational design and functionalization for specific applications (Das and Marsili, 2010; Han et al., 2011).

It is worth mentioning here some examples of AuNP biosynthesis of biotechnological relevance in virus, algae and electrochemically active bacteria.

Virus-mediated nanoparticle (VNP) synthesis offer the unique advantage of a size-constrained reaction cage (Douglas and Young, 1998) and displays robust functional groups on the surface of their capsids (Slocik et al., 2005). Biosynthesis of nanoparticles in virus finds application in material science and medicine. In general, VNPs are very small, monodispersed, stable and robust, and they might be produced with ease on large scale. Furthermore, VNPs can be modified by either genetic modification of the virus or chemical bioconjugation methods (Steinmetz and Manchester, 2011). Among other applications, viral material could be employed in the reduction of toxic environmental contaminants. For example, reduced iron nanoparticles produced in the filamentous M13 virus reduced soluble uranium (U6+) to its insoluble form (U4+) (Ling et al., 2008).

AuNPs biosynthesis has been reported also in the red alga Chondrus crispus and the green alga Spyrogira insignis (Castro et al., 2013). As dead biomass was used, the bioreduction was likely caused by deprotonated groups on the algal cell wall that act as centres of sorption.

Nanoparticle biosynthesis is essentially a reduction process followed by a stabilization step (capping). Electrochemically active bacteria are capable of metal reduction under a broad range of environmental conditions. Therefore, they can also produce nanoparticles as a by-product of their respiration. For example, washed Shewanella oneidensis cells incubated in minimal medium with Au3+ produced small spherical AuNPs (see also Table 2) through direct extracellular bioreduction (Anil et al., 2011). As this review focuses on AuNPs in fungi, we refer the reader to a recently published review on AuNPs in electroactive microorganisms (Kalathil et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Fungal species capable of AuNPs biosynthesis and location of biosynthetic AuNPs

| Species | Reaction conditions | Reaction time (h) | T (°C) | Shape | Size (nm) | AuNP location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | |||||||

| Alternaria alternate | Cell-free filtrate | 24 | RT | Spherical, triangular, hexagonal | 12 ± 5 | Sarkar et al., 2012 | |

| Aspergillus clavatus | Active biomass | 48–72 | RT | Triangular, spherical and hexagonal | 24.4 ± 11 | Extracellular | Verma et al., 2011 |

| Aspergillus niger | Cell-free filtrate | 96 | 28 ± 2 | Spherical, elliptical | 12.8 ± 5.6 | Bhambure et al., 2009 | |

| Aspergillus oryzae var. viridis | Active and inactive biomass and cell-free extract | 72–120 | 25 | Various shapes (cell-free filtrate), mostly spherical (biomass) | 10–60 | Mycelial surface | Binupriya et al., 2010a |

| Aspergillus sydowii | Active biomass | N.A. | N.A. | Spjherical (at 3 mM Au3+ concentration | 8.7–15.6 | Extracellular | Vala, 2014 |

| Candida albicans | Cytosolic extract | 24 | N.A. | Spherical | 20–40 | Chauhan et al., 2011 | |

| Non spherical | 60–80 | ||||||

| Colletotrichum sp. | Active biomass | 96 | 25–27 | Spherical | 8–40 | Mycelial surface | Shankar et al., 2003 |

| Large aggregates | Undefined | ||||||

| Cylindrocladium floridanum | Active biomass | 168 | 30 | Spherical | 5–35 | Outer surface of the cell wall | Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2011b |

| Epicoccum nigrum | Active biomass | 72 | 27–29 | ND | 5–50 | Intra- and extra-cellular | Sheikhloo et al., 2011 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Active biomass | 72 | N.A. | Spherical, triangular | 8–40 | Extracellular | Mukherjee et al., 2002 |

| Fusarium semitectum | Active biomass | 24 | RT | Spherical | 10–80 | Extracellular | Sawle et al., 2008 |

| Helminthosporum solani | Active biomass | 72 | 37 ± 1 | Spheres, rods, triangles, pentagons, pyramids, stars | 2–70 | Extracellular | Kumar et al., 2008 |

| Hormoconis resinae | Active biomass | 24 | 30 | Spherical | 3–20 | Extracellular | Mishra et al., 2010 |

| Neurospora crassa | Active biomass | 24 | 28 | Spherical | 32 (3–100) | Intracellular | Castro-Longoria et al., 2011 |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | Supernatant, cell-free filtrate, active biomass | 12–72 | 30 | Spherical, triangular and hexagonal | 10–60 | Extracellular | Mishra et al., 2011 |

| Penicillium rugulosum | Supernatant, cell-free filtrate, and growth medium | 8–24 | 30 | Spherical, triangular, hexagonal | 20–80 | Mishra et al., 2012b | |

| Spherical | 20–40 | ||||||

| Penicillium sp. 1-208 | Cell filtrate | 0.08 | N.A. | Spherical | 30–50 | Du et al., 2011 | |

| Active biomass | 8 | N.A. | 40–60 | Intracellular | |||

| Rhizopus orzyae | Cell-free filtrate | 24 | 30 | Spherical | 16–25 | Das et al., 2012a | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Active biomass | < 24 | 30 | Spherical | 15–20 | Cell wall | Sen et al., 2011 |

| > 24 | 30 | Cytoplasm | |||||

| Sclerotium rolfsii | Cell-free filtrate | N.A. | RT | Spherical | 25.2 ± 6.8 | Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2011a | |

| Verticillium sp. | Active biomass | 72 | 28 | Spherical | 20 ± 8 | Cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane | Mukherjee et al., 2001 |

| Volvariella volvacea | Cell-free extract | N.A. | N.A. | Triangular, spherical, hexagonal | 20–150 | Philip, 2009 | |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Active biomass | 120 | 30 | Various shape depending on Au3+ concentration | N.A. | Intracellular | Pimprikar et al., 2009 |

| Metal-tolerant fungal isolates | Active biomass | 24–48 | 28 | Spherical, trigonal, cubic, tetragonal and hexagonal | 9–18 | Intracellular | Gupta et al., 2011 |

| Bacteria | |||||||

| Bacillus megatherium D01 | Active biomass with dodecanethiol as capping agent | 9 | 26 | Spherical | 1.9 ± 0.8 | Extracellular | Wen et al., 2009 |

| Sulfate-reducing bacteria enrichment | Active biomass (high Au concentration) | 144 | RT | Spherical | < 10 | Intracellular and extracellular | Lengke and Southam, 2006 |

| Escherichia coli | Active biomass | 120 | RT | Spherical | 25 ± 8 | Bacterial surface | Du et al., 2007 |

| Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense | Active biomass | 1 | N.A. | Spherical | 10–40 | Intracellular | Cai et al., 2011 |

| Marinobacter Pelagius | Active biomass | 22 | N.A. | Spherical, triangular | 2–10 | Extracellular | Sharma et al., 2012 |

| Plectonema boryanum | Active biomass | 24 | 25 | Octahedral | ∼ 60 | Cell boundary | Lengke et al., 2006,2006 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Active biomass | 24 | 37 | Spherical | 40 ± 10 | Extracellular | Husseiny et al., 2007 |

| Rhodobacter Capsulatus | Active biomass | 24 | 30 | Spherical | N.A. | Cell surface and extracellular | Feng et al., 2007 |

| Rhodopseudomonas capsulata | Active biomass | 48 | RT | Spherical (pH 7) | 10–20 | Extracellular | He et al., 2007 |

| Planar (pH 4) | 50–400 | ||||||

| Rhodopseudomonas capsulata | Cell-free filtrate | 48 | 30 | Spherical (low Au3+ concentration) | 10–20 | He et al., 2008 | |

| Nanowires (high Au3+ concentration) | 50–60 (Diameter) | ||||||

| Shewanella algae | Unwashed active biomass | 0.5 | 25 | Spherical | 10–20 | Periplasmic space | Konishi et al., 2006 |

| Shewanella oneidensis | Active biomass | 48 | 30 | Spherical | 12 ± 5 | Extracellular | Suresh et al., 2011 |

Few references on AuNPs biosynthesis are reported for comparison in the second part of the table. RT, room temperature; N.A., not available.

Many reviews on metallic nanoparticle biosynthesis in bacteria have been already published (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2010; Thakkar et al., 2010). However, only a handful have reviewed the nanoparticle biosynthesis mechanism and attempted to compare the performance of various biosynthetic microorganisms. A good review is available for silver nanoparticle (AgNP) biosynthesis in bacteria, fungi and plants (Durán et al., 2011). Another review has described nanoparticles production in fungi but lacked both specific information and mechanistic insight on AuNPs biosynthesis (Dhillon et al., 2012).

Current biosynthetic methods have been tested only under laboratory conditions, with somewhat contradictory results and the scale up of biosynthetic processes to industrial applications appears challenging. Despite the theoretical advantage offered by the biosynthetic process over physicochemical processes, recent literature show that slow reaction time, poor reproducibility, insufficient characterization of the Au-reducing proteins, lack of control over the particle size and shape, wide particle size distribution and cumbersome standardization procedures limit the industrial applications of the AuNP biosynthesis process.

In this mini review, we discuss the mechanisms of AuNP biosynthesis in fungal biomass and fungal extract in light of the advantages that fungi offer over other eukaryotes and bacteria and propose possible strategies to overcome the above-mentioned limitations.

Fungal biosynthesis

While biosynthesis of AuNPs in bacteria is well understood (Rai et al., 2013), less than 30 fungal species have been investigated so far for AuNP biosynthesis (Table 2). The occurrence of AuNP biosynthetic capability in bacteria and fungi suggest that the reduction of Au3+ to form protein metal nanoconjugates is a common response to toxic stress, where the enzymatic machinery required is readily available in environmental microorganisms.

In general, the microbiology of fungi is much less investigated, mainly because fungi are difficult to characterize – their structure complicates the microscopic and mechanistic studies that are required for nanoparticle characterization in it. Under laboratory conditions, fungi grow at a similar biomass density to bacteria. For example, the biomass yield of a Rhizopus oryzae culture grown with glucose as a carbon/energy source in an aerated batch bioreactor was 0.55 g g−1 (Taherzadeh et al., 2003), whereas an Escherichia coli culture grown with glucose in a stirred tank reactor had a biomass yield of 0.31 g g−1 (Xu et al., 1999).

However, fungi have several advantages over bacteria for bioprocess, including AuNP biosynthesis. Fungi secrete large amounts of extracellular proteins with diverse functions. The so-called secretome include all of the secreted proteins into the extracellular space (Girard et al., 2013). The high concentration of the fungal secretome has been used for industrial production of homologous and heterologous proteins. For example, the expression of a functionally active class I fungal hydrophobin from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana has been reported (Kirkland and Keyhani, 2011). The tripeptide glutathione is a well-known reducing agent involved in metal reduction and is known to participate in cadmium sulfide (CdS) biosynthesis in yeasts and fungi. Recombinant expression of glutathione in E. coli resulted in CdS nanoparticle production (Chen et al., 2009). However, the knowledge of the fungal secretome is still at an early stage. The large and relatively unexplored fungal secretome is an advantage because of the role that extracellular proteins and enzymes have in Au reduction and AuNP capping.

Fungal biomass has been used to remove metal cations from water because of the high concentration of cationic biosorption sites (Das, 2010). Particularly at low pH, biosorption on fungal biomass is higher than on bacteria. For example, various Gram-negative bacteria can immobilize Au3+ at about 0.35 mM g−1 dry cells at pH 3 under non-viable conditions (Tsuruta, 2004). At pH 2.5, Aspergillus sp. can immobilize about 1 mM g−1 dry cells (Kuyucak and Volesky, 1988).

Based on published literature, it is not possible to compare bacteria and fungi in terms of their metal bioaccumulation ability. In fact, the experimental conditions adopted (e.g. pH, initial metal concentration, temperature) are not homogeneous. Most of the studies are merely descriptive, with little mechanistic information provided. This issue needs to be addressed to develop a general model for AuNP production in viable microorganisms. Repeatable biosynthetic experiments at the same biomass and metal concentration will provide a sound basis to assess metal nanoparticle biosynthesis across bacteria and fungi.

Mechanism of Au reduction

There are two main precursors of AuNPs in the biosynthetic process: (i) HAuCl4, which dissociates to Au3+ ions (Khan et al., 2013) and (ii) AuCl which dissociates to Au+ (Zeng et al., 2010). The Au+ precursor is much less investigated, likely because of the higher solubility of Au3+ ions as compared to Au+ ions. However, Au+ solubility may be increased through complexation with the appropriate ligands such as alkenes, alkylamines, alkylphosphines, alkanethiols, and halide ions (Zeng et al., 2010). While the single-electron reduction of Au+ to Au0 is comprised of a single step, the three-electron reduction process of Au3+ to Au0 is likely the combination of a number of chemical transformations (Das et al., 2012b).

AuNP formation can occur either in the intracellular or extracellular space (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Extracellular AuNP formation is commonly reported for fungi when Au3+ ions are trapped and reduced by proteins in the cell wall. Previous work with the fungus Verticillium sp. ruled out the possibility that reduced sugars in the cell wall are responsible for the reduction of Au3+ ions and suggested adsorption of AuCl4- ions on the cell-wall enzymes by electrostatic interaction with positively charged groups (e.g. lysine) (Mukherjee et al., 2002; Durán et al., 2011). In the case of intracellular AuNP formation, Au3+ ions diffuse through the cell membrane and are reduced by cystolic redox mediators (Das et al., 2012b). However, it is unclear whether the diffusion of the Au3+ ions through the membrane occurs via active bioaccumulation or passive biosorption. The latter might be caused by Au3+ ions toxicity, which increases the porosity of the cellular membrane. Another recent study reports the production of intracellular AuNPs in metal-tolerant Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus. The intracellular AuNPs have an average diameter of 22 ± 2 nm, slightly larger than those observed in the extracellular space. The enzymatic reduction mechanism of Au3+ is essentially the same for intracellular and extracellular AuNPs (Gupta and Bector, 2013).

Figure 1.

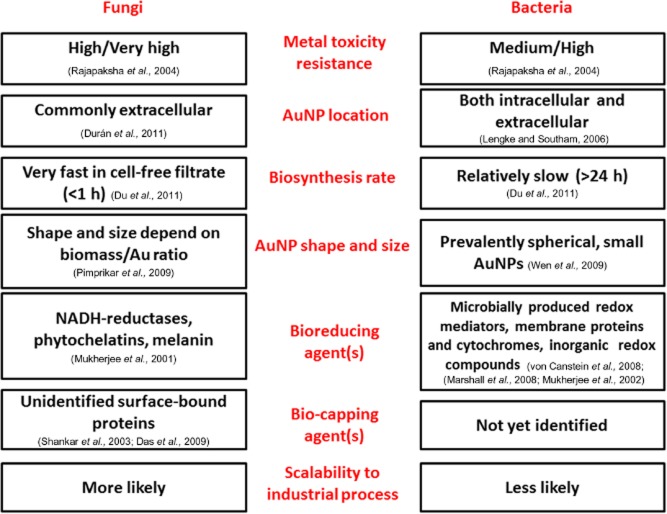

AuNP biosynthesis in fungi vs. bacteria.

Figure 2.

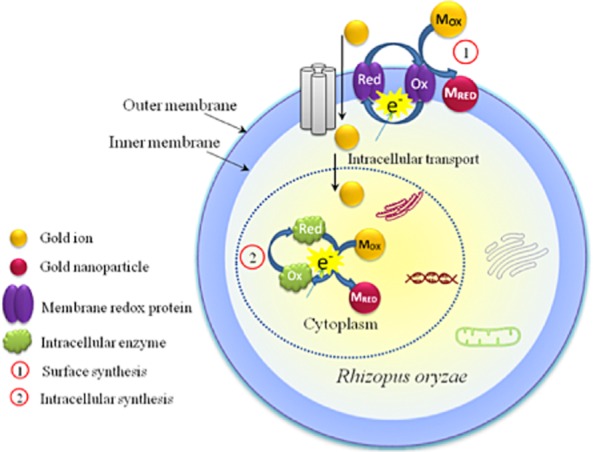

Schematic diagram of a proposed mechanism of Au biomineralization in Rhizopus oryzae (Reproduced with permission from Das et al., 2012b).

In viable cells, Au ions are reduced by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidoreductases either in the cell surface or in the cytoplasm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of R. oryzae showed that the Au+ concentration increases at the beginning of the biosynthetic process, then decreases, while the concentration of Au0 increased, demonstrating that Au3+ ions are first reduced to Au+ and then to Au0. The appearance of methylated Au3+ was proposed as an additional defence mechanism against metal toxicity (Das et al., 2012b).

The SDS-PAGE analysis of whole proteins from R. oryzae exposed to Au3+ showed up-regulated proteins similar to those observed in the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices exposed to Cd, Cu and Zn (Waschke et al., 2006). These results confirm that metals induce oxidative stress response genes. In R. oryzae, the up-regulation of those genes occurs at sub-toxic Au concentrations, while at higher concentrations, metal toxicity inhibits growth and protein expression (Das et al., 2012b).

Rhizopus oryzae shows evidence of intracellular reduction at high Au3+ concentrations, which may be associated with Au toxicity. High resolution transmission electron microscopy of the fungus R. oryzae incubated with Au3+ ions revealed the presence of electron dense particles in the cell-wall and cytoplasmic regions, suggesting that these regions are responsible for the reduction of Au3+ to Au0 (Das et al., 2011a).

Investigation on AuNPs biosynthesis by the soluble protein extract of fungi Fusarium oxysporum showed that NADH-dependent reductases are involved in the bioreduction process (Mukherjee et al., 2002). However, the specific protein(s) involved in Au reduction have not been yet identified. The appearance of a Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) peak at 1735 cm−1 in viable Phanerochaete chrysosporium biomass after interaction with the Au3+ ions might be relateed to the involvement of aromatic aminoacids like tyrosine and tryptophan in the reduction of Au3+ ions (Sanghi et al., 2011).

Other mechanisms for fungal AuNP biosynthesis have been proposed. The fungal pathogen Candida albicans is capable of synthesizing phytochelatins, which are made of chain links of glucose, cysteine and glycine ((c-Glu-Cys) n-Gly) by the transpeptidation reaction of c-Glu-Cys dipeptide from a succession of glutathione molecules. In the presence of glutathione, metal ions, including Au, trigger phytochelatin synthesis, in which Au3+ ions get reduced to AuNPs, which are then capped by glutathione (Chauhan et al., 2011).

AuNP synthesis has been detected by UV-visible spectrophotometry in heat-denatured cell-free filtrate of Sclerotium rolfsii in the presence of co-enzyme NADPH and 1 mM of Au3+. This indicates the involvement of thermostable NADPH-dependent enzymes in the AuNP biosynthesis process (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2011a). Cyclic voltammetry analysis showed that NADH produced from the fermentation of lactate by Hansenula anomala reduces Au3+ to AuNPs, despite AuNPs being rapidly reoxidized in lack of exogenous capping agents (Kumar et al., 2011).

The involvement of biosynthetic redox mediators in the fungal biosynthesis of AuNPs has been observed in Yarrowia lipolytica. These fungi secrete melanin (Apte et al., 2013), which interestingly appears to reduce Au3+ to AuNPs. However, experiments with melanin mutant and melanin-complemented strains have not been reported. Therefore, it is not certain if reduction by melanin is a plausible pathway in vivo. Further experiments from the same research group showed that melanin could mediate the reduction of metal salts to their elemental forms as nanostructures. Melanin is secreted in a phenol form and reduces Au3+ to Au0, while being oxidized to its quinone form (Apte et al., 2013).

Capping process

Small Au0 nanocrystals are unstable, and for this reason, fungi use extracellular proteins as capping agents to minimize AuNP aggregation and thus stabilize the nanocrystal. This process is analogous to the dispersion of AuNPs through chemical agents and results in the formation of dispersed AuNP with a broad particle size distribution. Full control of capping step in the AuNP biosynthesis process might result in the production of AuNP with narrow size and shape distribution that can be readily used in biomedical and industrial applications.

FTIR is the most commonly used method for the analysis of the capping and stabilizing ligands. Since fungi secrete a variety of enzymes and proteins, the specific organic molecule that acts as capping agent cannot be detected. However, the presence of organic molecules in the synthesized nanoparticles can be determined using FTIR. Additionally, the slight shift in the peaks of these functional groups to lower frequencies, which indicate that they might be involved in interactions with another group, thus confirming the capping mechanism. For example, possible involvement of phosphate bonds in AuNP capping was found in AuNPs synthesized by viable R. oryzae biomass by the shifting of FTIR bands from 1034 cm−1 to 1025 cm−1 corresponding to C-N stretching mode, when compared with the pristine biomass control bands (Das et al., 2009). The phosphate peak was observed to shift from 1033.6 to 1025.1 cm−1. This study also revealed the presence of amide I, II and III groups and the disappearance of carboxyl groups in the mycelia, which suggests the involvement of polypeptides in the biosynthetic mechanism (Das et al., 2009). The amide I, II and III peaks shifted from 1652.9, 1550 and 1379 cm−1 to 1635.5, 1544 and 1371.2 cm−1, respectively, indicating their involvement in capping process. Involvement of proteins in the capping of AuNPs was also indicated in the FTIR analysis of AuNPs synthesized by Aspergillus oryzae var. viridis by the observation of absorption bands at 1660 and 1530 cm−1, which corresponds to amide I and II bands, respectively (Binupriya et al., 2010b), which were also observed in AuNPs produced by Colletotrichum sp. by absorption bands at 1658, 1543 and 1240 cm−1, which corresponds to amide I, II and III bands respectively (Shankar et al., 2003).

AuNPs produced by both Penicillium brevicompactum (Mishra et al., 2011) and Penicilium rugulosum (Mishra et al., 2012b) showed a broad peak around 3100–3350 cm−1, which may correspond to stretching vibrations of amine (NH) or hydroxide (OH) groups. AuNPs synthesized by Alternaria alternata revealed absorption bands at 3,430 and 2,920 cm−1, which indicates the presence of O-H and aldehydic C-H stretching (Sarkar et al., 2012).

Two bands at 1383 and 1112 cm−1 detected by FTIR of freeze-dried AuNPs synthesized by Aspergillus niger can be assigned to the C-N stretching vibrations of aromatic and aliphatic amines (Bhambure et al., 2009). These amines were also detected in AuNPs synthesized by P. chrysosporium with absorption bands at 1367 and 1029 cm−1 (Sanghi et al., 2011). AuNPs produced by P. brevicompactum revealed peaks at 2970 cm−1, which suggests the involvement of carboxylic and phenolic groups (Mishra et al., 2011). FTIR of AuNPs produced by A. alternata showed an intense band at 1425 and 874 cm−1, indicating a C–H in plane deformation with aromatic ring stretching (Sarkar et al., 2012). The appearance of bands at 2854 and 1737 cm−1 from the same study corresponds to aromatic C–H anti-symmetric stretching vibration and C = O stretching vibration. These results suggest that proteins bind to AuNPs either through free amine, carboxyl or phosphate groups for stabilization (Sarkar et al., 2012). This amine linkage to AuNPs was also detected by the change in the absorption bands related to N atoms detected in AuNPs synthesized by P. chrysosporium. Furthermore, the aromatic amino acids tyrosine, tryptophan and sulfur containing the amino acids cysteine and methionine were found to be associated with AuNPs, while the disappearance of the –SH stretching band after interaction with Au ions indicates the formation of Au–S bonds (Sanghi et al., 2011). Three putative-capping proteins with a molecular weight of about 100, 25 and 19 kDa from AuNPs synthesized by F. oxysporum, were identified as plasma membrane ATPase, 3-glucan-binding protein and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zhang et al., 2011). The main FTIR results are summarized in Table 3. While FTIR results support the conclusion that proteins are involved in AuNPs capping and stabilization, the identification of the actual capping agent warrants further research.

Table 3.

FTIR characterization of AuNPs capping and stabilizing agents in various fungal species

| Species | Main FTIR peaks that shift following AuNP formation (cm−1) | Groups | Putative biomolecule | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizopus oryzae | 1652.9, 1550 and 1379 | Amide I, II and III | Surface-bound protein | Das et al., 2009 |

| Aspergillus oryzae var. viridis | 1660 and 1530 | Amide I and II | Proteins (through free carboxylate groups) | Binupriya et al., 2010a |

| Colletotrichum sp. | 1658, 1543 and 1240 | Amide I, II and III | Proteins | Shankar et al., 2003 |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | 3100–3350 (broad peak) | NH or OH | Mishra et al., 2011 | |

| Aspergillus niger | 1383 and 1112 | Aromatic and aliphatic C-N | Proteins | Bhambure et al., 2009 |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 1367 and 1029 | Aromatic and aliphatic C-N | Proteins | Sanghi et al., 2011 |

| Alternaria alternata | 1625, 1425, 874 and 1240 | Amide I,C-H deformation, C-H aromatic, and Amide III | Proteins | Sarkar et al., 2012 |

Comparison between bacterial vs. fungal biosynthesis of AuNPs

Comparing the efficiencies of AuNPs biosynthetic processes in different microorganisms is not straightforward (Fig. 1). The biosynthetic process in itself depends on various factors like temperature, pH, metal ion concentration and inoculum age, which differ widely across published work (Dhillon et al., 2012). Furthermore, morphological characterization (i.e. size, shape, distribution, crystallinity and growth kinetics) of the AuNPs is not reported routinely.

Rapid biosynthesis has been achieved in Penicillium sp. 1-208 cell filtrate, where near quantitative bioreduction and AuNP synthesis was obtained in just under 5 min. It is suggested that fungi secrete a large amount of extracellular enzymes in a relatively pure state, free from other cellular proteins. Suspension of fungal biomass in non-growth medium for 2 days prior to cell filtration increases the concentration of extracellular redox proteins (Du et al., 2011). The Au3+ bioreduction using viable fungal biomass of the same strain required about 8 h. Au3+ complete bioreduction time reported in Table 2 range from 8 h in Penicillium sp. 1-208 (Du et al., 2011) to 168 h in Cylindrocladium floridanum (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2011b). Much shorter reaction times are reported for AgNPs biosynthesis under light conditions, as fungal biomass catalyze light-driven reduction of Ag+ to Ag0 (Wei et al., 2014). However, initial appearance of AuNPs in viable Fusarium semitectum biomass after 4 h (Sawle et al., 2008) and even in a few minutes in Aspergillus terreus biomass (Priyadarshini et al., 2014). Rapid Au3+ bioreduction kinetics in cell-free filtrate of Trichoderma viride (Mishra et al., 2014) and Botrytis cinerea supernatant (Castro et al., 2014) confirms that the majority of Au-reducing proteins are secreted in the extracellular space and not associated with cell surface or cytoplasm.

Fungi produce AuNPs with a broader size distribution than bacteria. As the molecular biology of bacteria is much more established, they are currently preferred for AuNPs over fungi and other eukaryotic organisms (Kalathil et al., 2011). A systematic study on metal nanoparticle biosynthesis in about 200 fungal genera showed that only two species, Verticillium sp. and F. oxysporum, produced metal NPs (Du et al., 2011). Nevertheless, metallic NPs biosynthesis has been reported (Table 3) since then, as other fungal species have been investigated. Fungi show promises for industrial AuNP biosynthesis because of their easy handling (Binupriya et al., 2010b), larger protein secretion than bacteria, high biomass yield (Du et al., 2011), and accessibility for a scale up (Narayanan and Sakthivel, 2012b).

One of the major concerns against the use of biosynthetic AuNPs in biomedical applications is that these AuNPs carry proteins of fungal or bacterial origins as capping agents. Our immune system can recognize these proteins and promote an immune response similar to that observed during a fungal or bacterial infection. However, such immune response is an unwanted side-effect if AuNPs are used as drug carrier (Jain et al., 2012). Recent studies in immunology have shown that many microorganisms glycosylate their membrane proteins to reduce or even suppress the immune response of the host (Rudd et al., 2001). Glycosylation, either via microbially produced or host-produced oligosaccharides avoid recognition of the pathogen's proteins by the host-binding proteins, thus reducing or suppressing the innate immune response. For example, the rice blast fungus suppresses the rice immune response (Chen et al., 2014). Considering that glycosylation is much more prominent in fungal than in bacterial protein synthesis, fungal proteins involved in the capping and stabilization of AuNPs are also less likely to induce an immune response (Li and d'Anjou, 2009). As the study of microbiota exoglycome and their implications in the immune response are merely mentioned here, the interested reader should refer to a recent comprehensive review in this area.

Design of a bioreactor for AuNPs biosynthesis

AuNPs biosynthesis processes and nanoparticle biosynthesis in general are still carried out at laboratory scale using suspended fungal biomass or their cell-free extracts. Scale up of AuNPs biosynthesis will require bioreactors where the fungal biomass or the protein extracts are conveniently immobilized in a thin layer to minimize diffusional limitation as well as the time needed for biosynthesis. Furthermore, AuNPs should be easily recovered in the outlet after the bioreduction process to minimize downstream processing costs. Currently, there is no available report on fungal biomass reactors for AuNP biosynthesis. However, several bioreactors have been already described where fungal biomass serves as a catalyst for any given bioprocess (Ciudad et al., 2011; Djelal and Amrane, 2013; Yang et al., 2013). For example, P. chrysosporium was grown as thick biofilm (∼ 0.4–1.0 mm) on polysulfonic and tubular ceramic membranes (Sheldon and Small, 2005). More recently, high concentration of Rhizopus oligosporus fungal biomass was grown in a 2.5 L batch airlift bioreactor (Nitayavardhana et al., 2013). Contaminant removal from water was achieved using active Trametes versicolor biomass in a 10 L fluidized bed bioreactor (Morato et al., 2013). The design and the operative conditions of a bioreactor for AuNP biosynthesis largely depends on the concentration and location of nanoparticles (intracellular vs. extracellular) and the concentration of fungal biomass. Extracellular AuNPs must be purified from planktonic biomass, cell debris and cell secretome. Conventional stirred tank reactors such as those proposed to synthesize extracellular chitinases (Barghini et al., 2013) provide standardized operation and easy scale up but the downstream processing and the separation of biosynthetic AuNPs might prove less cost-effective. Other methods for metal nanoparticle purification include dialysis (Aqil et al., 2008) gel filtration, evaporation (Limayem et al., 2004), ion exchange (Zhang et al., 2010), centrifugation (Wulandari et al., 2008) and diafiltration (Sweeney et al., 2006). A possible strategy for nanoparticle purification could employ concentrated poly (ε-caprolactone) nanocapsules using crossflow filtration, followed by purification using dialysis (Limayem et al., 2004). Crossflow microfiltration is suitable for the processing of large nanoparticulate suspension volume, as the membrane surface can be increased according to the volume to be treated.

If AuNPs are transported inside the cell wall, then additional steps for their recovery, such as cell lysis will be needed, similar to those employed in the recovery of intracellular metabolites produced at industrial scale. However, these additional steps might render the process not feasible from an economic standpoint.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Green synthesis of AuNPs has attracted attention because of their reduced environmental toxicity. Bacterial and fungal biosynthesis of AuNPs offer similar process performance. However, fungi might be a better candidate for scale up because of the large amount of extracellular redox enzymes that they secrete. At a fundamental research level, poorly characterized fungi from diversity hotspots in tropical and equatorial environment may harbour novel pathways for metal nanoparticle synthesis. Finally, capping agents of fungal origin are less likely to stimulate an immune response like that induced by bacterial proteins.

Recent studies on extracellular synthesis of AuNPs in fungi suggest that the enzymatic machinery required for their biosynthesis is similar to that used for metal detoxification. Intracellular AuNP biosynthesis is reported to occur when there is a high Au3+ concentration available and when the membrane integrity is compromised to allow for Au3+ ions diffusion within the cell. However, there is no evidence available yet showing that fungi use biosynthetic nanoparticles for their metabolism.

Au bioreduction occurs in two main steps: (i) Au3+ is reduced to Au+ and (ii) Au+ is reduced to Au0. The frequent observation of one-step reduction of Au3+ to Au0 may be due to the short life of the Au+ form at ambient temperature. Controlled experimental conditions are needed to validate the Au bioreduction mechanism. Both proteins and other secondary metabolites may serve as capping and stabilizing agents for AuNP biosynthesis. Currently, only a handful of biomolecules involved in bioreduction and capping of AuNPs has been reported. Further research is needed to identify other species involved in the process.

The most desired candidates for large-scale AuNPs biosynthesis are those fungi that secrete large amount of extracellular enzymes and metabolites, resulting in the formation of well-dispersed AuNPs in the extracellular space. Among other candidates, the filamentous fungi Aspergillus and Trichoderma sp. produce numerous extracellular enzymes and metabolites of industrial interest (Meyer et al., 2011) and their genetics is reasonably well known. Therefore, they are excellent model organisms for in-depth genetic and biochemical investigation of bioreduction process.

Particle size distribution is probably the most important parameter, as small nanoparticles are very important as drug carriers and catalysts. In a NaBH4 chemical reduction process, highly monodispersed spherical nanoparticles with diameter < 5 nm diameter were obtained through accurate control of thiol-containing polymers that cap AuNPs, preventing their aggregation (Wang et al., 2007). In a physical bottom-up process employing microwaves, the use of high microwave power favours homogeneous nucleation, thus decreasing the AuNP size while increasing their uniformity. Monodispersed spherical AuNPs of 12 ± 1 nm diameter were produced (Seol et al., 2011). These results imply a higher control over the particle size and shape in chemical synthesis techniques.

Currently, AuNPs biosynthesis process in fungi does not compare favourably with the particle size distribution attainable in advanced physicochemical processes. Transmission electron microscopy-calculated particle size distributions are reported only for a small number of fungal species (Table 2). The particle size distributions reported in these studies is generally broader (10–40 nm) than that observed in physicochemical processes. Furthermore, the particle size distribution depends on the fungal catalyst used, the gold/biomass ratio and other process conditions. As microorganisms produce a variety of proteins that bind to nanoparticles of different sizes (Lundqvist et al., 2008), genetic and metabolic control of the nanoparticle production in viable fungal biomass is crucial for the reproducibility of the AuNP biosynthesis process.

The synthesis of highly stable AuNPs of defined shape and particle size distribution would require the optimization of numerous parameters, including pH, biomass/Au3+ ratio, and operative conditions of the bioreactor. However, with a proper optimization of these parameters, the above issue can be addressed. The slow kinetics of AuNP formation may be addressed by using cellular filtrate instead of viable biomass. If viable biomass is used, high surface bioreactors are needed to speed up the biosynthetic process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Greg Foley and Dr Seratna Guadarrama, for their advice in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Amoruso S, Nedyalkov NN, Wang X, Ausanio G, Bruzzese R. Atanasov PA. Ultrashort-pulse laser ablation of gold thin film targets: theory and experiment. Thin Solid Films. 2014;550:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Anil KS, Pelletier DA, Wang W, Broich ML, Moon J-W, Gu B, et al. Biofabrication of discrete spherical gold nanoparticles using the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2148–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte M, Girme G, Bankar A, Kumar R. Zinjarde S. 3, 4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine-derived melanin from Yarrowia lipolytica mediates the synthesis of silver and gold nanostructures. J Nanobiotechnology. 2013;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Qiu H, Greisch J, Jérôme R, De Pauw E. Jérôme C. Coating of gold nanoparticles by thermosensitive poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) end-capped by biotin. Polymer. 2008;49:1145–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Barghini P, Moscatelli D, Garzillo AMV, Crognale S. Fenice M. High production of cold-tolerant chitinases on shrimp wastes in bench-top bioreactor by the Antarctic fungus Lecanicillium muscarium CCFEE 5003: bioprocess optimization and characterization of two main enzymes. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2013;53:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhambure R, Bule M, Shaligram N, Kamat M. Singhal R. Extracellular biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Aspergillus niger - its characterisation and stability. Chem Eng Technol. 2009;32:1036–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya R. Mukherjee P. Biological properties of ‘naked’ metal nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1289–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhumkar DR, Joshi HM, Sastry M. Pokharkar VB. Chitosan reduced gold nanoparticles as novel carriers for transmucosal delivery of insulin. Pharm Res. 2007;2:1415–1426. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binupriya AR, Sathishkumar M, Vijayaraghavan K. Yun SI. Bioreduction of trivalent aurum to nano-crystalline gold particles by active and inactive cells and cell free extract of Aspergillus oryzae var. viridis. J Hazard Mater. 2010a;177:539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binupriya AR, Sathishkumar M. Yun SI. Biocrystallization of silver and gold ions by inactive cell filtrate of Rhizopus stolonifer. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2010b;79:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt EM, Bischoff S, Akob DM, Buchel G. Kusel K. Heavy metal tolerance of Fe(III)-reducing microbial communities in contaminated creek bank soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3132–3136. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02085-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F, Li J, Sun J. Ji Y. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by biosorption using Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense MSR-1. Chem Eng J. 2011;175:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- von Canstein H, Ogawa J, Shimizu S. Lloyd JR. Secretion of flavins by Shewanella species and their role in extracellular electron transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:615–623. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01387-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro L, Blázquez ML, Muñoz JA, González F. Ballester A. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using algae. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2013;7:109–116. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2012.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro ME, Cottet L. Castillo A. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by extracellular molecules produced by the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Materials Lett. 2014;115:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Longoria E, Vilchis-Nestor AR. Avalos-Borja M. Biosynthesis of silver, gold and bimetallic nanoparticles using the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;83:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A, Zubair S, Tufail S, Sherwani A, Sajid M, Raman SC, et al. Fungus-mediated biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles: potential in detection of liver cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2305–2319. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XL, Shi T, Yang J, Shi W, Gao X, Chen D, et al. N-glycosylation of effector proteins by an α-1,3-mannosyltransferase is required for the rice blast fungus to evade host innate immunity. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1360–1376. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Tuan HY, Tien CW, Lo WH, Liang HC. Hu YC. Augmented biosynthesis of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles by genetically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25:1260–1266. doi: 10.1002/btpr.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad G, Reyes I, Jorquera MA, Azocar L, Wick LY. Navia R. Novel three-phase bioreactor concept for fatty acid alkyl ester production using Rhizopus oryzae as whole cell catalyst. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27:2505–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Cölfen H. A crystal-clear view. Nature Mater. 2010;9:960–961. doi: 10.1038/nmat2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crookes-Goodson WJ, Slocik JM. Naik RR. Biodirected synthesis and assembly of nanomaterials. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;7:2403–2412. doi: 10.1039/b702825n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das N. Recovery of precious metals through biosorption – a review. Hydrometallurgy. 2010;103:180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Das SK. Marsili E. A green chemical approach for the synthesis of gold nanoparticles: characterization and mechanistic aspect. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2010;9:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Das AR. Guha AK. Gold nanoparticles: microbial synthesis and application in water hygiene management. Langmuir. 2009;25:8192–8199. doi: 10.1021/la900585p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Dickinson C, Laffir F, Brougham DF. Marsili E. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles biosynthesized with Rhizopus oryzae protein extract. Green Chem. 2012a;14:1322–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Liang J, Schmidt M, Laffir F. Marsili E. Biomineralization mechanism of gold by zygomycete fungi Rhizopous oryzae. ACS Nano. 2012b;6:6165–6173. doi: 10.1021/nn301502s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon GS, Brar SK, Kaur S. Verma M. Green approach for nanoparticle biosynthesis by fungi: current trends and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2012;32:49–73. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2010.550568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djelal H. Amrane A. Biodegradation by bioaugmentation of dairy wastewater by fungal consortium on a bioreactor lab-scale and on a pilot-scale. J Environ Sci. 2013;25:1906–1912. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(12)60239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong SA. Zhou SP. Photochemical synthesis of colloidal gold nanoparticles. Mater Sci Eng B. 2007;140:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas T. Young M. Host/guest encapsulation of materials by assembled virus protein cages. Nature. 1998;393:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Jiang H, Liu X. Wang E. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles assisted by Escherichia coli DH5a and its application on direct electrochemistry of haemoglobin. Electrochem Comm. 2007;9:1165–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Xian L. Feng J-X. Rapid extra-/intracellular biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by the fungus Penicillium sp. J Nanopart Res. 2011;13:921–930. [Google Scholar]

- Durán N, Marcato PD, Durán M, Yadav A, Gade A. Rai M. Mechanistic aspects in the biogenic synthesis of extracellular metal nanoparticles by peptides, bacteria, fungi, and plants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1609–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Yu Y, Wang Y. Lin X. Biosorption and bioreduction of trivalent aurum by photosynthetic bacteria Rhodobacter capsulatus. Curr Microbiol. 2007;55:402–408. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri LG, Radabaugh TR, Haynes PA. Hildebrand M. Identification of proteins from a cell wall fraction of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Insights into silica structure formation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:182–193. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500174-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Ishino Y, Ogawa A, Tsutumi K. Morita H. Cr(VI) reduction from contaminated soils by Aspergillus sp N2 and Penicillium sp. N3 isolated from chromium deposits. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2008;54:295–303. doi: 10.2323/jgam.54.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Han G, De M, Kim CK. Rotello VM. Gold Nanoparticles in delivery applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Daniel WL, Massich MD, Patel PC. Mirkin CA. Gold nanoparticles for biology and medicine. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:3280–3294. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard V, Dieryckx C, Job C. Job D. Secretomes: the fungal strike force. Proteomics. 2013;13:597–608. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. Mullins CB. Surface science investigations of oxidative chemistry on gold. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1063–1072. doi: 10.1021/ar8002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. Bector S. Biosynthesis of extracellular and intracellular gold nanoparticles by Aspergillus fumigatus and A. flavus. Anton Leeuw. 2013;103:1113–1123. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Devi S. Singh K. Biosynthesis and characterisation of Au- nanostructures by metal tolerant fungi. J Basic Microbiol. 2011;51:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ST, Zhou YE, Xu ZX, Roy VAL. Hung TF. Nanoparticle size dependent threshold voltage shifts in organic memory transistors. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:14575–14580. [Google Scholar]

- He S, Guo Z, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang J. Gu N. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using the bacteria Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Mater Lett. 2007;61:3984–3987. [Google Scholar]

- He S, Zhang Y, Guo Z. Gu N. Biological synthesis of gold nanowires using extract of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24:476–480. doi: 10.1021/bp0703174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Liao F, Molesa S, Redinger D. Subramanian V. Plastic-compatible low resistance printable gold nanoparticle conductors for flexible electronics. J Electrochem Soc. 2003;150:G412–G417. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S-H. Gold nanoparticle-based immunochromatographic assay for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2007;127:335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Husseiny MI, Abd El-Aziz M, Badr Y. Mahmoud MA. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2007;67:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain K, Kesharwani P, Gupta U. Jain NK. A review of glycosylated carriers for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4166–4186. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelveh S. Chithrani DB. Gold nanostructures as a platform for combinational therapy in future cancer therapeutics. Cancers. 2011;3:1081–1110. doi: 10.3390/cancers3011081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalathil S, Lee J. Hwan Cho M. Electrochemically active biofilm-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles in water. Green Chem. 2011;13:1482–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Kalathil S, Mansoob MM, Lee J. Hwan Cho M. Production of bioelectricity, bio-hydrogen, high value chemicals and bioinspired nanomaterials by electrochemically active biofilms. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawazu M, Nara M. Tsujino T. Preparation of Au-TiO2 hybrid nano particles in silicate film made by sol-gel method. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 2004;31:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MM, Kalathil S, Han TH, Lee J. Cho MH. Positively charged gold nanoparticles synthesized by electrochemically active biofilm-a biogenic approach. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13:6079–6085. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2013.7666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland BH. Keyhani NO. Expression and purification of a functionally active class I fungal hydrophobin from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana in Escherichia coli. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi Y, Tsukiyama T, Ohno K, Saitoh N, Nomura T. Nagamine S. Intracellular recovery of gold by microbial reduction of AuCl4- ions using the anaerobic bacterium Shewanella algae. Hydrometallurgy. 2006;81:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SA, Peter YA. Nadeau JL. Facile biosynthesis, separation and conjugation of gold nanoparticles to doxorubicin. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:495101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/49/495101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SK, Amutha R, Arumugam P. Berchmans S. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles: an ecofriendly approach using Hansenula anomala. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:1418–1425. doi: 10.1021/am200443j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyucak N. Volesky B. Biosorbents for recovery of metals from industrial solutions. Biotechnol Lett. 1988;10:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lengke M. Southam G. Bioaccumulation of gold by sulfate-reducing bacteria cultured in the presence of gold (I)-thiosulfate complex. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;70:3646–3661. [Google Scholar]

- Lengke MF, Ravel B, Fleet ME, Wanger G, Gordon RA. Southam G. Mechanisms of gold bioaccumulation by filamentous cyanobacteria from gold(III)-chloride complex. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:6304–6309. doi: 10.1021/es061040r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. d'Anjou M. Pharmacological significance of glycosylation in therapeutic proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limayem I, Charcoset C. Fessi H. Purification of nanoparticle suspensions by a concentration/diafiltration process. Sep Purif Technol. 2004;38:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ling T, Huimin Y, Shen Z, Wang H. Zhu J. Virus-mediated FCC iron nanoparticle induced synthesis of uranium dioxide nanocrystals. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:115608. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/11/115608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cu C, Cheng Y, Ma H. Liu D. Shape control technology during electrochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles. Int J Min Met Mater. 2013;20:486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Lovley DR. Cleaning up with genomes: applying molecular biology to bioremediation. Nature Rev. 2003;1:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Elia G, Lynch I, Cedervall T. Dawson KA. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mafuné F, Kohno J, Takeda Y. Kondow T. Formation of gold nanoparticles by laser ablation in aqueous solution of surfactant. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:5114–5120. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MJ, Plymale AE, Kennedy DW, Shi L, Wang Z, Reed SB, et al. Hydrogenase- and outer membrane c-type cytochrome-facilitated reduction of technetium (VII) by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:125–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Wu B. Ram AFJ. Aspergillus as a multi-purpose cell factory: current status and perspectives. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyre ME, Treguer-Delapierre M. Faure C. Radiation-induced synthesis of gold nanoparticles within lamellar phases. Formation of aligned colloidal gold by radiolysis. Langmuir. 2008;24:4421–4425. doi: 10.1021/la703650d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Tripathy SK, Wahab R, Jeong S-H, Hwang I, Yang Y, et al. Microbial synthesis of gold nanoparticles using the fungus Penicillium brevicompactum and their cytotoxic effects against mouse mayo blast cancer C2C12 cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92:617–630. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Tripathy SK. Yuna SI. Fungus mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their conjugation with genomic DNA isolated from Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Process Biochem. 2012b;47:701–711. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Kumari M, Pandey S, Chaudhry V, Gupta KC. Nautiyal CS. Biocatalytic and antimicrobial activities of gold nanoparticles synthesized by Trichoderma sp. Bioresour Technol. 2014;166:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AN, Bhadaurla S, Singh Gaur M. Pasricha R. Extracellular microbial synthesis of gold nanoparticles using fungus Hormoconis resinae. JOM. 2010;62:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mock JJ, Barbic M, Smith DR, Schultz DA. Schult S. Shape effects in plasmon resonance of individual colloidal silver nanoparticles. J Chem Phys. 2002;116:6755–6759. [Google Scholar]

- Morato CC, Climent H, Mozaz SR, Barcelo D, Urrea EM, Vicent T. Sarrà M. Degradation of pharmaceuticals in non-sterileurban wastewater by Trametes versicolor in a fluidized bed bioreactor. Water Res. 2013;47:5200–5210. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, Senapati S, Sainkar SR, Khan MI, et al. Bioreduction of AuCl4 ions by the fungus, Verticillium sp. and surface trapping of the gold nanoparticles formed. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:3585–3588. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011001)40:19<3585::aid-anie3585>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Senapati S, Mandal D, Ahmad A, Khan MI, Kumar R. Sastry M. Extracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Chembiochem. 2002;3:461–463. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020503)3:5<461::AID-CBIC461>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto M, Kashiwagi Y. Yamamoto M. Synthesis and size regulation of gold nanoparticles by controlled thermolysis of ammonium gold (I) thiolate in the absence or presence of amines. Inorg Chim Acta. 2005;358:4229–4236. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan KB. Sakthivel N. Biological Synthesis of metal nanoparticles by microbes. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;156:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan KB. Sakthivel N. Facile green synthesis of gold nanostructures by NADPH – dependent enzyme from the extract of Sclerotium rolfsii. Colloids Surf A. 2011a;380:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan KB. Sakthivel N. Synthesis and characterization of nano-gold composite using Cylindrocladium floridanum and its heterogeneous catalysis in the degradation of 4-nitrophenol. J Hazard Mater. 2011b;189:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitayavardhana S, Issarapayup K, Pavasant P. Khanal SK. Production of protein-rich fungal biomass in an airlift bioreactor using vinasse as substrate. Bioresour Technol. 2013;133:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okitsu K, Mizukoshi Y, Yamamoto TA, Maeda Y. Nagata Y. Sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles on chitosan. Mater Lett. 2007;61:3429–3431. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana R, Leavitt JJ, Comolli LR, Csencsits R, Janot N, Flanagan KA, et al. U(VI) reduction by diverse outer surface c-type cytochromes of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6369–6374. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02551-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci OD, Buck DC, Farrer JK. Watt RK. A ferritin mediated photochemical method to synthesize biocompatible catalytically active gold nanoparticles: size control synthesis for small (∼ 2 nm), medium (∼ 7 nm) or large (∼ 17 nm) nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2014;4:3472–3481. [Google Scholar]

- Philip D. Biosynthesis of Au, Ag and Au-Ag nanoparticles using edible mushroom extract. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2009;73:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimprikar PS, Joshi SS, Kumar AR, Zinjarde SS. Kulkarni SK. Influence of biomass and gold salt concentration on nanoparticle synthesis by the tropical marine yeast Yarrowia lipolytica NCIM 3589. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;74:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissuwan D, Cortie CH, Valenuela SM. Cortie MB. Functionalised gold nanoparticles for controlling pathogenic bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissuwan D, Niidome T. Cortie MB. The forthcoming applications of gold nanoparticles in drug and gene delivery systems. J Control Release. 2011;149:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshini E, Pradhan N, Sukla LB. Panda PK. Controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Aspergillus terreus IF0 and its antibacterial potential against Gram negative pathogenic bacteria. J Nanotechnol. 2014;2014:653198. [Google Scholar]

- Rai M, Ingle AP, Gupta IR, Birla SS, Yadav AP. Abd-Elsalam KA. Potential role of biological systems in formation of nanoparticles: mechanism of synthesis and biomedical applications. Curr Nanosci. 2013;9:576–587. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapaksha RMCP, Tobor-Kapłon MA. Bååth E. Metal toxicity affects fungal and bacterial activities in soil differently. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2966–2973. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.2966-2973.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd PM, Elliott T, Cresswell P, Wilson IA. Dwek RA. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science. 2001;291:2370–2376. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha K, Agasti SS, Kim C, Li X. Rotello VM. Gold nanoparticles in chemical and biological sensing. Chem Rev. 2012;112:2739–2779. doi: 10.1021/cr2001178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samal AK, Sreeprasad TS. Pradeep T. Investigation of the role of NaBH4 in the chemical synthesis of gold nanorods. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:1777–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghi R, Verma P. Puri S. Enzymatic formation of gold nanoparticles using Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Adv Chem Eng Sci. 2011;1:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar J, Ray S, Chattopadhyay D, Laskar A. Acharya K. Mycogenesis of gold nanoparticles using a phytopathogen Alternaria alternata. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2012;35:637–643. doi: 10.1007/s00449-011-0646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawle BD, Salimath B, Deshpande R, Bedre MD, Prabhakar BK. Venkataraman A. Biosynthesis and Stabilization of Au and Au-Ag alloy nanoparticles by fungus, Fusarium semitectum. Sci Tech Adv Mater. 2008;9:1–6. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/035012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüler D. Formation of magnetosomes in magnetotactic bacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen K, Sinha P. Lahiri S. Time dependent formation of gold nanoparticles in yeast cells: a comparative study. Biochem Eng J. 2011;55:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Seol SK, Kim D, Jung S. Hwu Y. Microwave synthesis of gold nanoparticles: effect of applied microwave power and solution pH. Mater Chem Phys. 2011;131:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar SS, Ahmad A, Pasricha R. Sastry M. Bioreduction of chloroaurate ions by geranium leaves and its endophytic fungus yields gold nanoparticles of different shapes. J Mater Chem. 2003;13:1822–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Pinnaka AK, Raje M, Fnu A, Bhattacharyya MS. Choudhury AR. Exploitation of marine bacteria for production of gold nanoparticles. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:86–91. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhloo Z, Salouti M. Katiraee F. Biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles by fungus Epicoccum nigrum. J Clust Sci. 2011;22:661–665. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon MS. Small HJ. Immobilisation and biofilm development of Phanerochaete chrysosporium on polysulphone and ceramic membranes. J Membrane Sci. 2005;236:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shulka R, Bansal V, Chaudhary M, Basu A, Bhonde RR. Sastry M. Biocompatibility of gold nanoparticles and their endocytotic fate inside the cellular compartment: a microscopic overview. Langmuir. 2005;21:10644–10654. doi: 10.1021/la0513712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocik JM, Naik RR, Stone MO. Wright DW. Viral templates for gold nanoparticle synthesis. J Mater Chem. 2005;15:749–753. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Rivera Gil P, Zhang F, Zanella M. Parak WJ. Biological applications of gold nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1896–1908. doi: 10.1039/b712170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz NF. Manchester M. Viral Nanoparticles: Tools for Materials Science & Biomedicine. Singapore: Pan Stanford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Storhoff JJ, Marla SS, Bao P, Hagenow S, Mehta H, Lucas A, et al. Gold nanoparticle-based detection of genomic DNA targets on microarrays using a novel optical detection system. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;19:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh AK, Pelletier DA, Wang W, Broich ML, Moon J-W, Gu B, et al. Biofabrication of discrete spherical gold nanoparticles using the metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2148–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney S, Woehrle G. Hutchison JE. Rapid purification and size separation of gold nanoparticles via diafiltration. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3190–3197. doi: 10.1021/ja0558241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taherzadeh MJ, Fox M, Hjorth H. Edebo L. Production of mycelium biomass and ethanol from paper pulp sulfite liquor by Rhizopus oryzae. Bioresour Technol. 2003;88:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(03)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar KN, Mhatre SS. Parikh RY. Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta T. Biosorption and recycling of gold using various microorganisms. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2004;50:221–228. doi: 10.2323/jgam.50.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vala AK. Exploration on green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sydowii. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2014 . doi: 10.1002/ep.11949. [Google Scholar]

- Verma VC, Singh SK, Solanki R. Prakash S. Biofabrication of anisotropic gold nanotriangles using extract of endophytic Aspergillus clavatus as a dual functional reductant and stabilizer. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9743-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Law N, Pearson G, van Dongen BE, Jarvis RM, Goodacre R. Lloyd JR. Impact of silver (I) on the metabolism of Shewanella oneidensis. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1143–1150. doi: 10.1128/JB.01277-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Tan B, Hussain I, Schaeffer N, Wyatt MF, Brust M. Cooper AI. Design of polymeric stabilizers for size-controlled synthesis of monodisperse gold nanoparticles in water. Langmuir. 2007;23:885–895. doi: 10.1021/la062623h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangoo N, Bhasin KK, Boro R. Suri CR. Facile synthesis and functionalization of water-soluble gold nanoparticles for a bioprobe. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;6:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani IA. Ahmad T. Size and shape dependant antifungal activity of gold nanoparticles: a case study of Candida. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;101:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschke A, Sieh D, Tamasloukht M, Fischer K, Mann P. Franken P. Identification of heavy metal-induced genes encoding glutathione S-transferases in the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices. Mycorrhiza. 2006;17:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00572-006-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Zhou H, Xu L, Luo M. Liu H. Sunlight-induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by animal and fungus biomass and their characterization. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2014;89:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, Lin Z, Gu P, Zhou J, Yao B, Chen G. Fu J. Extracellular biosynthesis of monodispersed gold nanoparticles by a SAM capping route. J Nanopart Res. 2009;11:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Weng CH, Huang CC, Yeh CS, Lei YH. Lee GB. Synthesis of hexagonal gold nanoparticles using a microfluidic reaction system. J Micromec Microeng. 2008;18:035019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zan X, Li S, Liu Y, Cui C, Zou B, Zhang W, et al. In situ synthesis of large-area single sub-10nm nanoparticle arrays by polymer pen lithography. Nanoscale. 2014;6:749–752. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulandari P, Li X, Tamada K. Hara M. Conformational study of citrates adsorbed on gold nanoparticles using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J Nonlinear Opt Phys Mater. 2008;17:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Jahic M, Blomsten G. Enfors SO. Glucose overflow metabolism and mixed-acid fermentation in aerobic large-scale fed-batch processes with Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:564–571. doi: 10.1007/s002530051433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Hai FI, Nghiem LD, Nguyen LN, Roddick F. Price WE. Removal of bisphenol A and diclofenac by a novel fungal membrane bioreactor operated under non-sterile conditions. Int Biodeter Biodegr. 2013;85:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Zeng X, Li H, Chen P, Ye C. Zhao F. Synthesis and characterization of nano-silica/polyacrylate composite emulsions by sol-gel method and in-situ emulsion polymerization. J Macromol Sci A. 2011;48:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Young JR, Davis SA, Bown PR. Mann S. Coccolith ultrastructure and biomineralisation. J Struct Biol. 1999;126:195–215. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Ma Y, Jeong U. Xia Y. Au(I): an alternative and potentially better precursor than Au(III) for the synthesis of Au nanostructures. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2290–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, He X, Wang K. Yang X. Different active biomolecules involved in biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by three fungus species. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7:245–254. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Ross R. Roeder R. Preparation of functionalized gold nanoparticles as a targeted X-ray contrast agent for damaged bone tissue. Nanoscale. 2010;2:582–586. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00317g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Xu W, Liu G, Panda D. Chen P. Size-dependent catalytic activity and dynamics of gold nanoparticles at the single-molecule level. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:139–146. doi: 10.1021/ja904307n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]