Abstract

Purpose

To examine whether associations between perceived discrimination and heavy episodic drinking (HED) varies by age and by discrimination type (e.g., racial, age, physical appearance) among African American youth.

Methods

National data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Transition to Adulthood Study were analyzed. Youth participated in up to four interviews (2005, 2007, 2009, 2011; n=657) between ages 18–25. Respondents reported past-year engagement in HED (4 or more drinks for females, 5 or more drinks for males), and frequency of discriminatory acts experienced (e.g., receiving poor service, being treated with less courtesy). Categorical latent growth curve models, including perceived discrimination types (racial, age, and physical appearance) as a time-varying predictors of HED, were run in MPlus. Controls for gender, birth cohort, living arrangement in adolescence, familial wealth, parental alcohol use, and college attendance were explored.

Results

The average HED trajectory was curvilinear (increasing followed by flattening), while perceived discrimination remained flat with age. In models including controls, odds of HED were significantly higher than average around ages 20–21 with greater frequency of perceived racial discrimination; associations were not significant at other ages. Discrimination attributed to age or physical appearance was not associated with HED at any age.

Conclusions

Perceived racial discrimination may be a particularly salient risk factor for HED around the ages of transition to legal access to alcohol among African American youth. Interventions to reduce discrimination or its impact could be targeted before this transition to ameliorate the negative outcomes associated with HED.

Keywords: Discrimination, heavy episodic drinking, early adulthood, minority health

Alcohol use is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among U.S. youth,1 with heavy episodic drinking (HED; on a single occasion, 5 or more drinks in a row for a male or 4 or more for a female) increasing risk of adverse outcomes.2,3 On average, HED increases, stabilizes, then declines in the transition to early adulthood (ages 18–25).4 Factors affecting trajectories include exiting the parental home and college attendance (for the increase)5 and social role transitions such as marriage, childbirth and full time employment (for the decrease).6

African American youth start drinking alcohol later than their White peers, drink less overall, and are less likely to maintain alcohol use throughout early and mid-adolescence once initiated.7 However, among young adult heavy drinkers, African Americans are more likely than Whites to continue heavy drinking after their early twenties.8 Also, although African American young adults drink less on average than Whites, they experience more alcohol-associated social and health-related problems.9,10 Due to these disparate outcomes, and racial differences in substance use risk factors, researchers have called for more studies of alcohol use development in African American youth.10

One important determinant of African American youths’ behavioral health is racial discrimination. Discrimination operates through individual and social pathways to affect behavior. Consistent with the stress and coping model, discrimination acts as a threatening environmental stressor which elicits physiological, cognitive and behavioral responses to overcome that threat.11 Immediate physiological reactions to discrimination include increased cortisol and blood pressure.12 Discrimination also affects emotional states and self-control resources.13 Anger, depression, reduced self-control and coping motives are pathways by which perceived racial discrimination affects alcohol-related problems among African American youth.14,15

Consistent with the social development model, discrimination can also affect bonding with important people and institutions, and thus affect HED and other problematic behaviors.16 In another study, authors found that the effects of perceived discrimination on subsequent substance use (including alcohol) among African American adolescents was fully mediated by decreases in school engagement and increases in affiliations substance using peers.17

Life course theory also posits that the timing of exposures during development matters in their impact.18 The importance of timing of discrimination exposure has been suggested in the literature, but not yet empirically tested. In a study linking discrimination experiences in pre-adolescence to later substance use, authors hypothesized that the development of identity during the preteen years, along with the development of cognitive capacity to understand abstract social groupings, made discrimination exposure during this life period especially salient.19 However, authors did not test age differences in effects of exposure to discrimination and did not examine effects at older ages (older adolescents/young adults).

In the present study, we extend past research in a number of ways, First, we examine discrimination’s links with an outcome not yet tested – HED. Associations between discrimination and HED may differ from associations with alcohol-related problems due to African American youths’ lower levels of consumption and HED compared to other ethnic groups.7 Second, we examine multiple types of discrimination. Research suggests African American youth experience multiple discrimination types, such as body weight, social class and gender discrimination.20 These types have been negatively associated with well-being measures.21 Third, we focus on early adulthood, and test age-specific effects of discrimination. Both exposure to discrimination and HED increase on average during adolescence, although there is diversity in trajectories for both.22,23 Discrimination effects may change with age due to these changing frequencies. Further, leaving the parental home during early adulthood, especially given the importance of parental norms’ protective effect against alcohol use among Black teens,24 as well as changes in legal access to alcohol at age 21, may influence age patterning of associations.

In the current study we examined how perceived discrimination is associated with HED over time within a national sample of African American young adults followed between ages 18–25. We controlled for other factors that have been linked to HED among young adults, including respondent sex, family-of-origin wealth, parental alcohol use, and college attendance. We expected discrimination to be significantly positively associated with HED. We also expected that the strength of the association between discrimination and HED would vary according to discrimination type, with the strongest effects observed for racial discrimination. This was due to our belief that age and physical appearance represent more transitory and malleable aspects of identity, while racial identification carries with it familial and historical meaning more fundamental to identity. Finally, we also expected these associations would vary by age, with a jump in the strength of associations at age 21 when alcohol becomes more easily legally accessible.

METHODS

Data

Data from the Panel Study on Income Dynamics - Transition to Adulthood Study (PSID-TA) were analyzed.25 The PSID was initiated in 1968 with a national, household-based sample of families (n=4,802). The study purpose was to assess the impact of the War on Poverty. The sample was drawn to be nationally-representative, with an over-sample of Census enumeration districts with large non-White populations.26 Families have been interviewed every two years since, including family branch-offs (i.e., when a son or daughter establishes his or her own household). In 1997/99, new immigrant families were added to enhance representativeness. After applying sampling weights provided by the study team, this sample still closely resembles the U.S. population today.27

In 1997, researchers began the PSID Child Development Study (CDS) to collect information on child development on a random subsample of PSID children ages 0–12. Interviews were conducted with 2,380 families about 3,563 children (response rate 88%). Children who remained under 18 were re-interviewed in 2002/2003 and 2007/2008.28 In 2005, the PSID-TA was initiated to follow CDS participants ages 18 and older.25 In 2005, 745 participants were interviewed (88.8% response rate);29 in 2007/08, 1,118 persons were interviewed (90% response rate);30 in 2009, 1,556 respondents were interviewed (92% response rate); and in 2011, 1,907 respondents were interviewed (92% response rate). In total, 2,155 unique persons participated in one or more TA waves.

We made a number of restrictions to our analysis sample. First, we limited to youth who self-reported African American/Black race/ethnicity, because of our interest in this group of youth (n=1,455). Second, we limited to respondents who were 18 or older as of 2009 (n=830)1 and who participated in two or more TA waves (n=668), as having fewer waves made trajectory analyses less stable. Another 11 respondents were excluded due to missingness on time-invariant exogenous variables. The final sample included 657 individuals nested in 538 families. Persons excluded from the analysis due either to missing covariates or having fewer than two waves of data (n=173) were significantly more likely to be male and less likely to live with both biological parents at CDS baseline compared to those included in the sample (n=657). The present secondary data analysis was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Tulane University.

Measures

Outcome

In each TA wave, participants were asked “How many days in the past year did you have 4 (if female) / 5 (if male) or more drinks in a row?” Participants responded zero to 365 days. Because very few respondents reported HED more than 3 times in the past year (<10%), responses were dichotomized to reflect any versus no HED. Responses were then transformed to age-based indicators of HED based on youths’ age at each TA wave.

Main predictors

In each TA wave, respondents were asked questions about unfair treatment assessing chronic, routine, and less overt experiences of discrimination. Questions were drawn from the National Survey of American Life, and included items such as “You are treated with less courtesy than other people,” “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores,” and “People act as if they think you are not smart.”31 Respondents were asked how often seven types of discrimination occurred in their day-to-day lives with response options on a zero to five scale (0=never to 5=almost every day.) Respondents were also asked a follow-up question about the main reason for the discrimination experienced (asked as a global question about all previous experiences): ancestry or natural origins/ gender/ race/ age/ height or weight/ some other aspect of physical appearance/ other. The maximum frequency across unfair treatment experiences was used to reflect the frequency of perceived discrimination. Frequency scores were categorized according to the reported main reason for discrimination. For example, if the respondent reported the main reason for discrimination was racial, the score reflected frequency of racial discrimination, and other discrimination types were coded zero. Frequency scores were constructed for racial/ancestry discrimination, age discrimination, and physical appearance discrimination. Variables representing other types of discrimination (gender, height or weight) were not constructed due to the low proportion of respondents reporting these as the main reasons for discrimination experienced.

Controls

Respondents’ biological sex was classified as male (=1) or female (=0) based on the sex reported by their parent at CDS intake. Past studies have consistently found males engage in HED more frequently than females.32

The PSID asks household heads (i.e., TA respondents’ parents) a long list of questions about household assets (i.e., home value, savings, income from various sources, etc.) as well as debt obligations (i.e., amount owed on mortgage, student loans, car loan, etc.). A constructed household wealth measure is provided by PSID researchers based on a summary of these measures. Because of the wide range in values, respondents were categorized into wealth quartiles (1=lowest to 4=highest) based on their family’s wealth in 2005 (i.e., the first year of the PSID-TA). Past studies have found that youth with more economic assets are more likely to use alcohol and to engage in HED.33,34

In the 1999 and 2001 main PSID interview, the head of household responded to questions about his/her own and spouse’s (when applicable) alcohol use. They were asked, “[Do you/ does your spouse] ever drink any alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor?” (yes/no) and, if they responded yes, “On average, [do you/ does your spouse] have less than one drink a day, one or two drinks in a day, three to four drinks a day, or five or more drinks a day?” The higher alcohol use of either the head or spouse in 2001 was used as a measure of parental alcohol use during childhood/adolescence, with responses from 1999 substituted if 2001 was missing. Parental alcohol use is associated with young adult alcohol use.35

At each wave, respondents reported whether they currently attended college. A variable reflecting any college attendance at any wave was then constructed (1=yes, 0=no). Studies suggest rates of HED are higher among college attendees than others.5

Controls for birth cohort and living arrangement at Wave I of the CDS (living with both biologic parents vs. not) were also explored. However, since neither of these was significantly associated with the outcomes in multivariable analyses, they were dropped for parsimony.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses (frequencies, means) were conducted in Stata 13, and latent curve modeling (LCM) was conducted in MPlus version 7.36 Latent curve models are an extension of structural equation models which estimate growth parameters (intercept and slope) without measurement error.37,38 Descriptive analyses included sampling weights, and all analyses used adjusted standard errors to account for non-independence of individuals due to family-based sampling. Robust full information maximum likelihood estimation was used for LCM, with the dependent variables (HED at each wave) specified as categorical. The first analytic step was fitting an LCM for HED without predictors, including testing for nonlinearities using polynomial terms.

After determining trajectory form, three models with different predictors were run: (1) racial discrimination, (2) age discrimination, and (3) physical appearance discrimination. Discrimination types were examined separately due to their collinearity (i.e., a non-zero score on one discrimination type determined a zero score on the other two types because of question wording). Discrimination variables were included as time-varying predictors of age-specific variability in HED, above and beyond the average HED trajectory. Respondent sex, parental alcohol use frequency, familial wealth and college attendance were added as time-invariant controls. The final set of control variables was derived based on backwards elimination (i.e., non-significant differences in scaled log likelihood differences between nested models). Linear regression coefficients were estimated for continuous dependent variables (e.g., the latent curve parameters) and log odds were estimated for categorical dependent variables (e.g., HED).

RESULTS

Descriptives

Table 1 presents sample characteristics (unweighted n’s and weighted percentages). Nearly half of participants were ages 10–13 at their intake to the CDS study in 1997. There were somewhat fewer females in the sample compared to males (45.5% vs. 54.5%). Nearly two-thirds (65.3%) of included youth did not live with both biologic parents at CDS intake. Also, youth were over-represented in lower wealth quartiles compared to the overall PSID-TA sample, with almost half (46.0%) being in the lowest quartile of family wealth. Slightly over half of youths’ parents reported not drinking alcohol, with another substantial minority reporting less than daily alcohol use (37.9%). Nearly sixty percent of youth attended college during early adulthood.

Table 1.

Characteristics of African American youth in the Panel Study on Income Dynamics – Transition to Adulthood Study (n=657)

| n (weighted %)

|

|

|---|---|

| Age at CDS intake | |

| 3–6 years | 109 (19.2%) |

| 7–9 years | 242 (38.8%) |

| 10–13 years | 306 (41.9%) |

| Biological sex | |

| Female | 332 (45.5%) |

| Male | 325 (54.5%) |

| Living arrangement at CDS intake | |

| With both biologic parents | 254 (34.7%) |

| Biological mother only | 341 (55.3%) |

| Biological father only | 20 (3.2%) |

| No biological parents | 42 (6.8%) |

| Wealth quartilea | |

| 1 (Lowest) | 244 (46.0%) |

| 2 | 228 (29.8%) |

| 3 | 136 (16.6%) |

| 4 (Highest) | 49 (7.8%) |

| Average daily parental alcohol use | |

| Do not drink alcohol | 335 (51.5%) |

| Less than once a day | 229 (37.9%) |

| 1–2 a day | 68 (6.9%) |

| 3–4 a day | 19 (3.1%) |

| 5 or more a day | 6 (0.5%) |

| Any college attendance | |

| No | 270 (43.6%) |

| Yes | 387 (56.4%) |

Quartiles based on entire PSID-TA sample, not African American subsample

Table 2 presents the proportion of respondents who reported each main reason for perceived discrimination, by age. At nearly every age (except age 18), race/ancestry was the most common reported main reason for discrimination. At all ages except age 18, between one-quarter to one-third of respondents reported racial bias as the main reason for discrimination experiences. Discrimination due to age was the second most common reported reason, and discrimination due to physical appearance (other than gender, race, height/weight) was the third most common. Between 12–21% of African American youth reported experiencing infrequent (less than yearly) or no unfair treatment at each age.

Table 2.

Main reason for perceived discrimination, by agea

| 18 yrs (%) | 19 yrs (%) | 20 yrs (%) | 21 yrs (%) | 22 yrs (%) | 23 yrs (%) | 24 yrs (%) | 25 yrs (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Race/Ancestry | 24.5 | 27.3 | 31.5 | 29.1 | 26.3 | 30.6 | 34.3 | 32.3 |

| Age | 25.8 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 22.3 | 24.6 | 17.9 | 13.9 | 20.6 |

| Phys appearance | 12.6 | 13.9 | 11.0 | 12.3 | 8.0 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 16.1 |

| Gender | 8.2 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 6.6 | 4.5 |

| Height/weight | 9.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 10.3 |

| Other | 3.8 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 3.9 |

| N/A, no experience | 15.7 | 15.1 | 16.8 | 16.1 | 21.0 | 18.7 | 19.9 | 12.3 |

Types of unfair treatment surveyed: treated with less courtesy than other people; received poorer service than other people at stores and restaurants; people act as if they think you are not smart; people act as if they are afraid of you; people act as if they think you are dishonest; people act as if they are better than you; you are treated with less respect than other people.

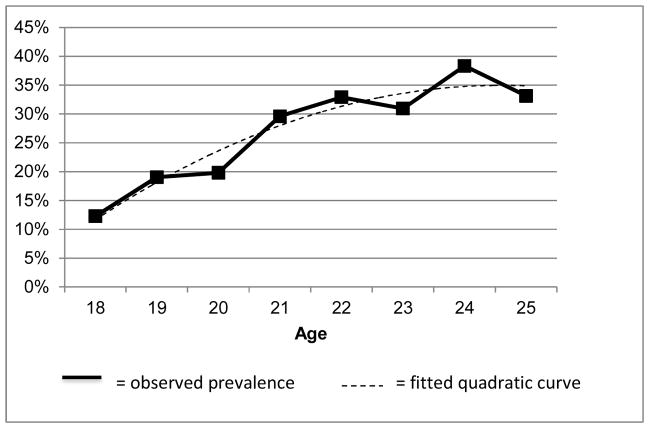

Figure 1 presents the average frequency of discrimination experiences by age, according to the main reason for discrimination. Average frequencies were calculated for the whole sample (left panel) as well as among those reporting some experience with the discrimination type (right panel). Within the whole sample, frequencies of all three discrimination types were relatively stable across age (p for linear trend racial discrimination = 0.16; age discrimination = 0.22; physical appearance discrimination = 0.46). In the whole sample, racial discrimination was the most frequent across most ages. However, when limiting to those reporting discrimination experiences, age-based discrimination was most frequent across ages.

Figure 1. Frequency of different discrimination types by agea.

aFrequency of discrimination was measured on a 0–4 scale (0=never/less than once a year, 1=a few times a year, 2=a few times a month, 3= at least once a week, and 4=almost every day).

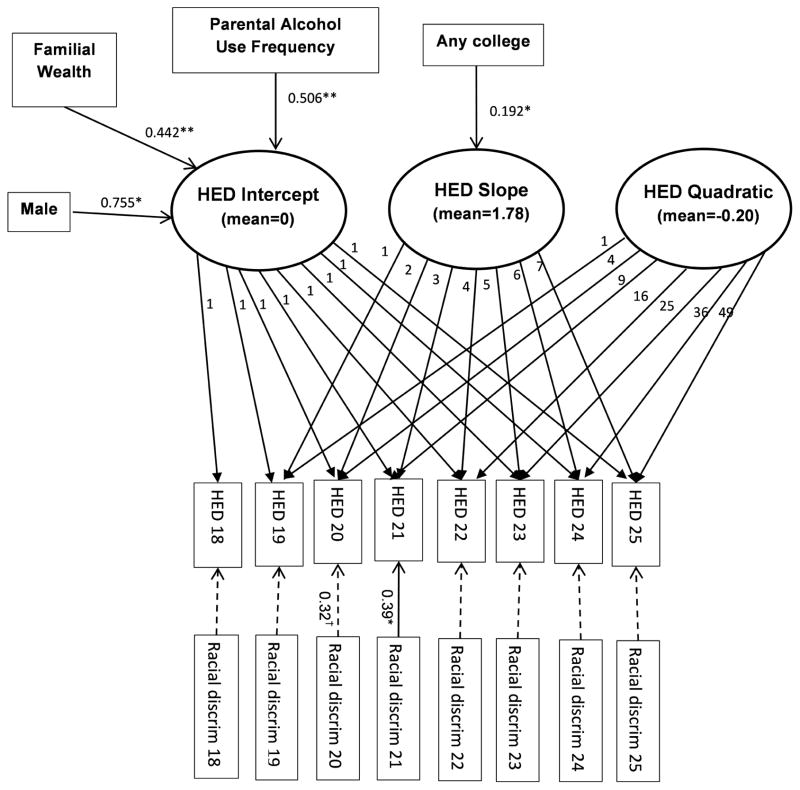

Figure 2 presents the prevalence of past year HED according to age. Although relatively few youth reported HED at age 18 (12.3%), by age 25, approximately 33% of youth reported past year HED. HED prevalence increased steadily until age 22, where prevalence appeared to plateau.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of past year heavy episodic drinking, by age

Growth Models

Null models were run comparing the fit of a linear versus quadratic model. Fit indices (i.e., AIC and BIC) suggested the quadratic model fit better. Also, the estimated quadratic term was significant. Therefore, the quadratic growth model was selected. In the null model, the growth factors suggested an initial increase in the odds of past year HED that slowed with age (linear mean=−1.405, p<.001, quadratic mean= −0.135, p=0.002). Variance estimates around the intercept and slope were statistically significant, but non-significant for the quadratic, suggesting some between-person variability in HED trajectory shapes.

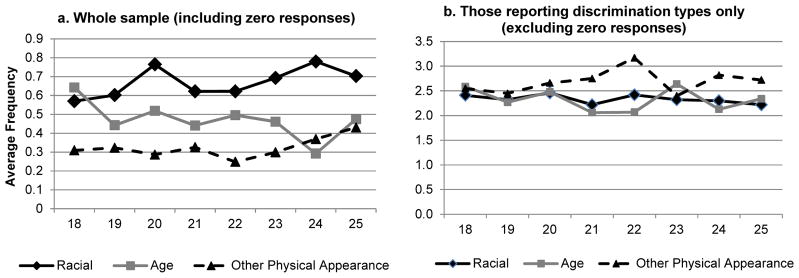

Figure 3 presents the results of the multivariate LCM. Perceived racial discrimination was significantly positively associated with deviations from the average HED trajectory only at age 21 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–2.05), although it was borderline associated with higher-than-average HED at age 20 (AOR=1.38, 95% CI 0.99–1.91). Being a male versus female (β̂ =0.76, 95% CI 0.19–1.33), higher parental alcohol use (β̂ =0.51, 95% CI 0.14–0.87), and parental wealth (β̂ =0.44, 95% CI 0.13–0.75) were all associated with higher initial levels of HED. Attending college at one or more waves was associated with a steeper increase in HED over time (β̂ =0.19, 95% CI 0.02–0.36).

Figure 3. Latent curve model results: Racial discrimination as a time-varying predictor of heavy episodic drinking among African American young adults.

†p<0.10 *p<0.05 **p<0.01

aLoglikelihood = −899.626; AIC = 1841.252; BIC = 1935.493; sample size adjusted BIC = 1868.818; no estimates of RMSEA, CFI/TLI are available for maximum likelihood estimation with categorical dependent variables

bParameter estimates are betas for OLS regression onto the intercept and slope, and are log odds for regressions onto categorical variables (HED). Pathways represented with a dashed line are non-significant. For figure parsimony, disturbances are not depicted. Covariances between growth parameters were non-significant in the final model.

cAge discrimination and physical appearance discrimination were not significantly associated with HED at any age.

Separate models using age discrimination or physical appearance discrimination as time-varying predictors of HED were also run. In these models, neither age nor physical appearance discrimination were found to be significantly associated with HED at any age.

Additional analyses

Due to concern that racial discrimination may be under-represented when only asking about the main reason for discrimination, post-hoc analyses were performed using data from the 2009 and 2011 surveys when a question asking about additional reasons for unfair treatment was included. Among all respondents included in the given survey year, we tested cross-sectional associations between racial discrimination and HED two ways: (1) when racial discrimination was the reported main reason for discrimination, and (2) when racial discrimination was either the main reason or a secondary/tertiary/etc. reason for discrimination. Only a small proportion of respondents (n=58 in 2009, n=66 in 2011) reported that racial bias was a secondary reason for discrimination. Therefore it appears that when discrimination is perceived to be racially motivated, respondents are most likely to report that as the main reason for discrimination. Also, associations between racial discrimination and HED (assessed with bivariate logistic regression models) were only slightly different when accounting for both main and secondary reasons for discrimination versus main reason only (see appendix 1). Therefore we believe our analyses are not significantly biased when we only take into account the main perceived reason for discrimination.

APPENDIX 1.

Associations between racial discrimination frequency and HEDa

| Main reason only OR (95% CI) |

Main or secondary reason OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Survey Year | ||

| 2009 | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) | 1.10 (1.04–1.17) |

| 2011 | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | 1.12 (1.06–1.19) |

Cross-sectional analyses conducted with entire available sample in each wave. Bivariate logistic regression models regressing HED on racial discrimination frequency when reported either as a main reason (first column) or when reported as a main or secondary reason (second column).

DISCUSSION

Persons experiencing racial discrimination evidenced a significantly higher odds of HED at age 21, and marginally higher odds of HED at age 20, than would be expected given the average trajectory of HED among the sample. These results extend past studies which found racial discrimination associated with greater alcohol problems among African American youth at various ages cross-sectionally, though none of the previous studies have examined differences by age, and none have examined HED as an outcome.14,15 Associations at ages 20 and 21 suggest that discrimination experiences around the transition to legal alcohol access may be particularly salient. It is possible that discrimination has a stronger effect at these ages due to youth living apart from parents and their increased alcohol access around these ages. Past studies have found parents exert important protective effects against African American teens’ substance use initiation, and help buffer the negative effects of experienced racism on emotional and coping responses.24,39 Future studies that examine interactions between these various influences, and that model mediators of discrimination effects, are warranted.

The lack of association between age and physical appearance discrimination and HED among African American youth is a novel finding. This contrasts with other research during adolescence which finds multiple types of discrimination associated with adverse mental health outcomes.21 Given the transitory and malleable nature of these dimensions of identity, it is possible that discrimination in these domains during early adulthood is less threatening to one’s self-esteem and sense of self-worth. It is also possible that given the unique historical underpinnings of racial discrimination, discrimination of this type carries more weight in affecting mental health and behavior. According to historical trauma theory, massive trauma inflicted on a population (such as slavery) can have lasting deleterious effects across generations.40 Future research which examines differences between types of discrimination may help explicate these differences.

Despite the strengths of this study, such as the inclusion of a large, national sample of African American youth, its findings should be interpreted with knowledge of the study’s limitations. Data come from a long-running intergenerational study, and thus may be not representative of the U.S. African American population. In analyses examining differences between the unweighted and weighted sample (available upon request), the unweighted sample was slightly wealthier than the weighted sample. Thus the trajectory analyses conducted without weights may be somewhat biased towards higher HED prevalence. Replicating the analyses with other datasets may test the generalizability of findings. Additionally, persons who participated in only one TA wave were excluded from the analysis. There were some demographic differences between included versus excluded individuals, which could bias our study results in unpredictable directions. Discrimination was measured contemporaneous to HED, which makes disentangling causal direction difficult. One-year time-lagged models did not converge due to most respondents participating in surveys every other year (e.g., ages 18 and 20, ages 19 and 21, etc.). Future studies incorporating temporal ordering are warranted. Finally, we were not able to assess main reasons for discrimination for each individual act. This may result in an under-estimation of experienced racial discrimination in the current study. Future studies which have more nuanced attribution questions can re-examine this association.

In conclusion, we found that perceived racial discrimination was associated with higher-than-average HED at age 21, and borderline associated with HED at age 20, among African American youth. Although ultimately one should work towards a less discriminatory society, findings suggest that in the meantime, interventions to impact substance use among this group, particularly the disparate continuation rates of HED into adulthood among African American youth,7 may be especially needed around the ages when youth transition to legal alcohol purchase. Although past research findings suggest that promising targets for interventions may be emotional and coping responses to discrimination, or social relationships that impact discrimination’s effects, further research is warranted exploring the mechanisms by which discrimination affects HED at these ages.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This study found that among African American youth ages 18–25, perceived racial discrimination was associated with higher than average heavy episodic drinking (HED) at ages 20 and 21. Age and physical appearance discrimination were not associated with HED. Age-targeted interventions to reduce discrimination experiences’ impact should be considered.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, grant number 1K01AA021368-01A1.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HED

Heavy episodic drinking

- PSID

Panel Study on Income Dynamics

- PSID-TA

Panel Study on Income Dynamics Transition to Adulthood Study

- PSID-CDS

Panel Study on Income Dynamics Childhood Development Study

- LCM

latent curve models

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Respondents who were not yet 18 as of 2009 would not have had the ability to complete the two interviews needed for trajectory analyses.

Previous versions of this manuscript have been presented at the 2014 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and the 2014 Minority Health and Health Disparities Conference.

No persons other than the listed co-authors have contributed significantly to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Aubrey Spriggs Madkour, Email: aspriggs@tulane.edu.

Kristina Jackson, Email: kristina_jackson@brown.edu.

Heng Wang, Email: hwang8@tulane.edu.

Thomas T. Miles, Email: tmiles@tulane.edu.

Frances Mather, Email: fmather@tulane.edu.

Arti Shankar, Email: sarti@tulane.edu.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004 Mar 10;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J, Naimi T, Brewer R, Jones S. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American Collegiate Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Initiation and course of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2005;17:29–47. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48626-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, et al. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(Special Issue 04):917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malone PS, Northrup TF, Masyn KE, Lamis DA, Lamont AE. Initiation and persistence of alcohol use in United States Black, Hispanic, and White male and female youth. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(3):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costanzo PR, Malone PS, Belsky D, Kertesz S, Pletcher M, Sloan FA. Longitudinal Differences in Alcohol Use in Early Adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(5):727–737. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2009 Apr;33(4):654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godette DC, Headen S, Ford CL. Windows of opportunity: fundamental concepts for understanding alcohol-related disparities experienced by young Blacks in the United States. Prevention science : the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2006 Dec;7(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark R, Anderson N, Clark V, Williams D. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inzlicht M, McKay L, Aronson J. Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science. 2006;17(3):262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boynton M, O’Hara R, Covault J, Scott D, Tennen H. A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(2):228–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons F, O’Hara R, Stock M, Gerrard M, Weng C, Wills T. The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(5):1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalano RF, Hawkins D. The Social Development Model: A Theory of Antisocial Behavior. In: Hawkins J, editor. Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brody GH, Kogan SM, Chen Y-f. Perceived Discrimination and Longitudinal Increases in Adolescent Substance Use: Gender Differences and Mediational Pathways. American journal of public health. 2012 May 1;102(5):1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder GH, Johnson MK, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons FX, Yeh H-C, Gerrard M, et al. Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(Supplement 1):S27–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Weightism, Racism, Classism, and Sexism: Shared Forms of Harassment in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Wall MM, Piran N, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple Types of Harassment: Associations With Emotional Well-Being and Unhealthy Behaviors in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(6):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith-Bynum MA, Lambert SF, English D, Ialongo NS. Associations between trajectories of perceived racial discrimination and psychological symptoms among African American adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2014 Nov;26(4 Pt 1):1049–1065. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental psychology. 2006 Mar;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Gillmore MR, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Ethnic Differences in Family Factors Related to Early Drug Initiation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(3):208–217. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGonagle KA, Sastry N. Cohort Profile: The Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Child Development Supplement and Transition into Adulthood Study. International journal of epidemiology. 2014 Apr 4; doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGonagle KA, Schoeni RF, Sastry N, Freedman VA. The Panel Study of Income Dynamics: Overview, recent innovations, and potential for life course research. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. 2012;3(2):268–284. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v3i2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement: User Guide for CDS-III. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Child Development Supplement Transition into Adulthood 2005 User Guide. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed SM, Yonas MA, Coyne-Beasley T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2012 Mar;87(3):285–291. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182441680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams D, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress, and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research. 2014;35(2):193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melotti R, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Araya R, Lewis G. Adolescent Alcohol and Tobacco Use and Early Socioeconomic Position: The ALSPAC Birth Cohort. Pediatrics. 2011 Apr 1;127(4):e948–e955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humensky JL. Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2010;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholte RHJ, Poelen EAP, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Engels RCME. Relative risks of adolescent and young adult alcohol use: The role of drinking fathers, mothers, siblings, and friends. Addictive behaviors. 2008;33(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulenberg J, Maggs JL. Moving Targets: Modeling Developmental Trajectories of Adolescent Alcohol Misuse, Individual and Peer Risk Factors, and Intervention Effects. Applied Developmental Science. 2001 Oct 1;5(4):237–253. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan TE, Duncan SC. An introduction to latent growth curve modeling. Behavior Therapy. 2004 Spr;35(2):333–363. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived Discrimination and Substance Use in African American Parents and Their Children: A Panel Study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(4):517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sotero MM. A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2006;1(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.