Abstract

Embryonic morphogenesis takes place via a series of dramatic collective cell movements. The mechanisms that coordinate these intricate structural transformations across an entire organism are not well understood. In this study, we used gentle mechanical deformation of developing zebrafish embryos to probe the role of physical forces in generating long-range intercellular coordination during epiboly, the process in which the blastoderm spreads over the yolk cell. Geometric distortion of the embryo resulted in nonuniform blastoderm migration and realignment of the anterior-posterior (AP) axis, as defined by the locations at which the head and tail form, toward the new long axis of the embryo and away from the initial animal-vegetal axis defined by the starting location of the blastoderm. We found that local alterations in the rate of blastoderm migration correlated with the local geometry of the embryo. Chemical disruption of the contractile ring of actin and myosin immediately vegetal to the blastoderm margin via Ca2+ reduction or treatment with blebbistatin restored uniform migration and eliminated AP axis reorientation in mechanically deformed embryos; it also resulted in cellular disorganization at the blastoderm margin. Our results support a model in which tension generated by the contractile actomyosin ring coordinates epiboly on both the organismal and cellular scales. Our observations likewise suggest that the AP axis is distinct from the initial animal-vegetal axis in zebrafish.

Introduction

Robust morphogenetic patterning during embryonic development requires control of cell movements over distances much larger than individual cells (1,2). Although cells in culture exhibit collective migration in some circumstances (3), they do not exhibit the exquisite long-range coordination commonly observed during development. This and other observations imply that cues intrinsic to intact organisms are essential in driving morphogenetic patterning.

In this study, we use zebrafish embryos as a model system to investigate the mechanisms by which mechanical cues coordinate morphogenetic movements. In zebrafish, the first observable large-scale cell movement occurs during epiboly, when the blastoderm spreads across the yolk cell from the animal pole to the vegetal pole (Fig. 1 A) (4). During this process, cell migration is coordinated across the entire length of the blastoderm margin (∼3 mm at 50% epiboly). How the cells at the blastoderm margin coordinate migration over such a large distance is, to our knowledge, not understood.

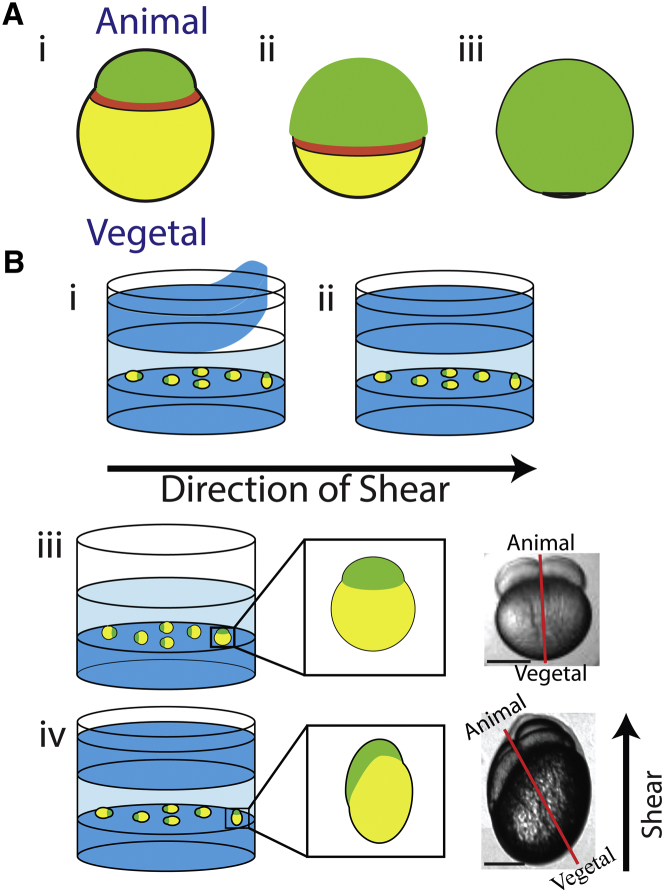

Figure 1.

Mechanical deformation probes the role of CCT in zebrafish epiboly. (A) (i) Schematic representation of epiboly. The blastoderm mass (green) begins at the animal pole of the yolk (yellow). Over time the blastoderm spreads over the yolk (ii (50% epiboly)) until it converges at the vegetal pole (iii). An actomyosin contractile band (red) forms just vegetal of the blastoderm margin. (B) Schematic depiction of directional compression, showing 1.4% w/v agarose (dark blue) and 0.8% w/v low-melting-point agarose (light blue). (i and ii) Agarose overlays are applied directionally to generate a shear direction. (iii) Embryos mounted in agarose are initially symmetric. (iv) Addition of an agarose overlay gently compresses the embryos, causing them to become asymmetric and introducing a new long axis at an angle relative to the AV axis. The shear direction in (iv) is rotated 90° into the page from (i) and (ii). Scale bar, 250 μm.

The actin band, a contractile ring of actin and myosin, assembles immediately vegetal to the blastoderm margin, and generates a contractile force termed cable constriction tension (CCT) (Fig. 1 A) (5–8). It is important to note that similar contractile actomyosin bands are observed across many biological processes, for example, during epithelial wound healing (9,10) and dorsal closure in Drosophila (11–13). Until recently, a prevailing hypothesis concerning the role of these analogous actomyosin structures was that they drive blastoderm migration (zebrafish), dorsal closure (Drosophila), and epithelial wound contraction by constricting the cell sheet in a purse-string-like fashion (8). However, recent observations have prompted a reevaluation of this model. Laser cutting of the actin band does not slow the rate of dorsal closure in Drosophila (12). Further, zebrafish embryos that are physically constrained to adopt a cylindrical shape successfully complete epiboly even though the force from CCT cannot contribute to the progress of epiboly in this geometry (5). Thus, at present, the function of the actin band and CCT during these processes is unclear.

In zebrafish, the role of CCT in development has been difficult to determine, in part because the embryo is normally symmetric about the animal-vegetal (AV) axis, resulting in uniform CCT along the blastoderm margin. We used gentle mechanical compression in the form of an agarose overlay to alter the shape of the embryo (Fig. 1 B). This manipulation removes the initial symmetry about the AV axis, allowing an imbalance of forces to emerge. We then imaged cells along the blastoderm margin to examine the role of CCT in coordinating the migration of neighboring cells. As discussed below, disruption of CCT leads to striking changes in blastoderm migration on both the cellular and global length scales. A quantitative physical model based on force balance within the embryo accounts for these observations and suggests that CCT acts to coordinate cell movement during epiboly.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of media varying in Ca2+ concentrations

A 20× stock of E2 buffer was prepared by mixing 300 mM NaCl (BP358-212, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), 10 mM KCl (P217-500), 20 mM CaCl2 (C79-500, Fisher), 20 mM MgSO4 (194833, MP Biomedicals, Burlingame, CA), 3 mM KH2PO4 (BP362-500, Fisher), 1 mM Na2HPO4 (PB 332-500 Fisher) and adjusting the pH to 7.0 using HCl. A calcium-free stock of 20× E2 buffer was made by mixing the salts mentioned above without CaCl2 and adjusting the pH to 7.0 using NaOH. Media of differing final Ca2+ concentrations were achieved by mixing the two stocks at varying ratios.

Zebrafish embryo preparation

All embryos used in these experiments were obtained by mating either TL wildtype zebrafish embryos or Tg(actb2:Hsa.MAP7-EGFP)hm1 zebrafish (14). Embryos were harvested 30 min postfertilization and dechorionated using pronase. Briefly, embryos were placed in a 1 mg/mL solution of pronase (P6911-5G, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (14025, Life Technologies, South San Francisco, CA) for 1–5 min until the chorions spontaneously detached from the embryo. The embryos were then transferred to a solution of 16 mM EDTA (15576-028, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) in HBSS for 2 min to quench the pronase. Quenching was followed by washing the embryos in a solution of HBSS for 2 min. Following chorion removal, embryos were washed in the corresponding media (E2 ± Ca2+ ± blebbistatin (1852, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN)) three times and then mounted in 0.8% low-melting-point agarose. In compression experiments, an additional agarose overlay (3 mL of 1.4% agarose made in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes the previous night) was applied on top of the solidified mounting agarose to provide compression (Fig. 1). Time-lapse bright-field images of the embryos were taken every 4–8 min over the course of 24 h using a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope maintained at 28°C. Embryos grown in 62.5 μM Ca2+ media exhibit ∼8% mortality in the first 24 h of development (4/50). Embryos grown in the presence of blebbistatin have ∼80% mortality in the first 24 h of development (41/50).

Fixing and staining of zebrafish embryos

Embryos were grown until the desired time point and fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. After fixing, embryos were washed three times in PBS at 5 min intervals, followed by two washes in PBS + 0.1% Tween (PBST) at 5 min intervals. A final wash was conducted in PBST + 1% dimethylsulfoxide (PBSTD) for 5 min. The embryos were then placed into a blocking solution of 10% bovine serum albumin in PBSTD for 2 h at room temperature. After blocking, the embryos were labeled with 1 μg/mL tetramethylrhodamine (TMR)-phalloidin for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, then washed extensively (at least six times) in a solution of 1% bovine serum albumin in PBSTD. The fixed and stained embryos were imaged using a spinning-disk confocal on a Nikon Ti-E or a point-scanning confocal on a Leica SP5 in the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility.

Image analysis

All calculations of rates and angles in zebrafish were performed on embryos post invagination to ensure that calculated velocities are not affected by the momentary pause in epiboly during invagination. We observe that invagination occurs at ∼30% epiboly in compressed embryos. Our analysis thus makes use of data recorded in embryos at between 30% and 80% epiboly. Movies were initially processed in Fiji (15) to enhance the contrast between the blastula and the yolk. In addition, a Canny-Deriche edge detection algorithm was applied to generate an image that outlines the boundary of the entire embryo (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Subsequent data analysis was performed using MATLAB. The tangent vector of each point along the boundary of the embryo was calculated by taking the numerical derivative over 25 points neighboring the point. During epiboly, approximate locations of the blastoderm edges were tracked at 8- to 10-min intervals by manual selection. A more accurate blastoderm edge location was then calculated by finding the nearest point in the boundary image to the manually selected point. Migration rates were then determined by dividing the distance that the blastoderm traveled along the edge of the embryo by the time between each measurement.

The cosθ term used (see below, Eqs. 1–4) was calculated by taking the dot product of the tangent vector, as defined above, with the magnitude of the vector normalized to unity, with the normalized cable constriction vector determined by the line connecting the left and right edges of the blastoderm margin. Finally, the rate of epiboly was calculated by finding the arc length between the current and previous edges of the blastoderm margin and dividing by the time between the two points.

MATLAB modeling and simulations

For the 2D simulations, we used the binary edge image found using the Canny-Deriche algorithm (described above and shown in Fig. S1) to set the geometry of the embryo. The left and right edges of the blastoderm provided the initial starting locations for the blastoderm margin. In the 3D models, we used an ellipsoid geometry, as described in the Supporting Material, with an initial blastoderm location found by cutting a plane through the ellipsoid to form the initial ring. To perform the simulation, we tracked the movement of 100 points along the ring during their simulated migration across the surface of the ellipsoidal embryo. In both 2D and 3D simulations, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation performed in MATLAB with the basal tangential rate of epiboly set at 40 nm/s, except in the high blebbistatin case in which epiboly was set at 22 nm/s to mirror the slowing of epiboly observed experimentally. For MATLAB models of epiboly that incorporated CCT, we set the contribution of CCT at the experimentally determined value of 28 nm/s. For each step of the Monte Carlo simulation in both 2D and 3D, we calculated how much each edge moved during the step, and advanced that distance along the edge of the binary edge image. After each step, the tangential and CCT vectors were recalculated at the new locations. In models of embryos in which CCT was perturbed to mirror epiboly in embryos grown in reduced calcium media or blebbistatin, we set the CCT contribution to 0 nm/s.

Tracking the roughness of the margin

Confocal stacks recorded for TMR-phalloidin-stained embryos were flattened using a maximum intensity projection. The boundaries of the cells on the margin were manually tracked and a cell center was calculated by finding the center of the boundary of the cells (Fig. S2). These centers were used to calculate the vectors between neighboring cells.

Results

Epiboly does not progress uniformly in asymmetric embryos

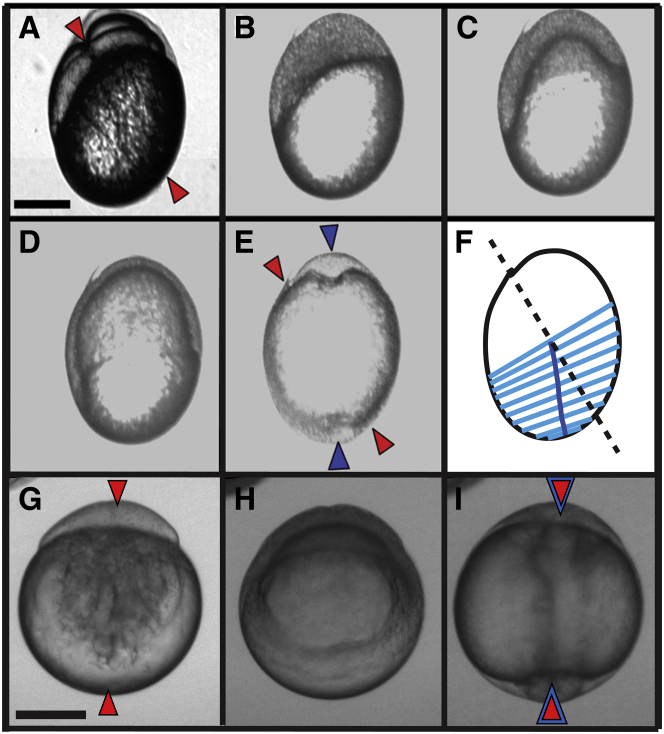

We first tested the role of CCT by removing the symmetry of embryos about the AV axis. We accomplished this by gently shearing dechorionated embryos via directional compression using an agarose overlay (Fig. 1 B). In these asymmetric embryos, we observe that the blastoderm mass, and consequently the initial AV axis, lies at an angle relative to the new long axis of the embryo. The blastoderm remains in this off-axis position throughout cell division and the mid-blastula transition (MBT) (Fig. 2, A and B). After MBT, the edges of the blastoderm progress at different velocities throughout epiboly. We observe that the trailing edge migrates faster, and thus traverses a greater distance, than the leading edge (Fig. 2, C–E, and Movie S1). As a result, the blastoderm margin rotates toward an alignment perpendicular to the long axis of the embryo (Fig. 2, E and F). In contrast, blastoderm margin migration progresses uniformly in uncompressed embryos (Fig. 2, G–I). These results suggest that mechanical compression breaks the symmetry of the embryo and alters the rates of epiboly unequally along the edges of the blastoderm.

Figure 2.

Development of a compressed embryo from the four-cell stage to the conclusion of epiboly shows alterations in the local rate of epiboly and reorientation of the embryonic AP axis. (A–F) Compressed embryo in the four-cell stage (A), immediately after the MBT (B), at 30% epiboly (C), at 70% epiboly (D), and immediately after blastopore closure (E). The trailing, right edge migrates farther than the leading, left edge. Red triangles indicate the initial AV axis orientation and blue triangles the AP axis. (F) Light blue lines connect the left and right edges of the blastoderm margin at successive time points. Faster migration along the right side of the embryo causes the center of the blastoderm margin (dark blue line) to rotate relative to the initial AV axis (black dashed line). (G–I) Uncompressed embryo at the one-cell stage (G), at 50% epiboly (H; note that both edges have progressed equal distances at this time), and immediately after blastopore closure (I). Red triangles represent the initial AV axis and blue triangles the AP axis at the conclusion of epiboly. Note that in the uncompressed embryos, the AV and AP axes are aligned. Scale bar, 250 μm. (See also Movie S1.)

Differences in velocity and force depend upon local shape

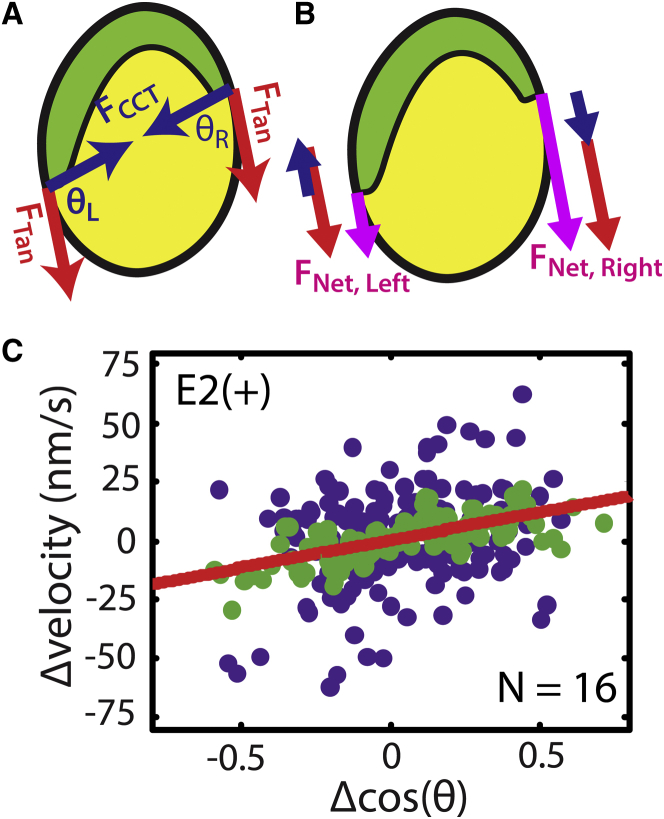

We observe blastoderm reorientation in compressed embryos of diverse shapes, indicating that this observation is unlikely to reflect a specific embryo geometry (Fig. S3). Instead, it is likely that blastoderm reorientation reflects an imbalance of forces at the blastoderm margin. Previous studies identified two major forces during blastoderm migration: CCT, which is directed toward the center of the actin ring; and a tangential component, which is directed along the surface of the embryo and generated by a combination of flow friction (5), microtubule dynamics (16–18), blastula retraction (19), and/or other processes (20,21). We define an asymmetry factor, Δcosθ, which is the difference in the cosines of the tangent and CCT vectors on the two edges of the embryos (cosθL and cosθR; Fig. 3 A). In an unperturbed, symmetric embryo, Δcosθ is close to zero. In shape-perturbed embryos, Δcosθ provides a simple metric for how much the shape is changed. A plot of the difference in blastoderm migration rates on the left and right sides of the compressed embryos (Δv) versus Δcosθ reveals a positive linear correlation (Fig. 3 C). Although there is significant variability in the data due to variations in the mounting agarose, variations in the orientation at which the zebrafish embryo lies relative to the imaging plane (ideally, the anterior-posterior (AP) axis forms perpendicularly to the imaging plane for this experiment), or innate differences between the individual embryos, a general trend emerges in which higher Δv and Δcosθ are correlated (Fig. 3 C). This observation suggests that an imbalance of local forces emerges from imposed shape asymmetries, which in turn leads to different migration velocities at the leading and lagging edges of the blastoderm margin. The slope of a linear fit to the data in Fig. 3 C yields a value of 23 ± 6 nm s−1. This value gives a measure of how fast reorientation occurs. Importantly, it is the same order of magnitude as the rate of epiboly (40 ± 4 nm s−1; mean ± SE), as determined from the rates of epiboly measured across 16 embryos grown in normal E2 media.

Figure 3.

Differential BM migration can be quantified via a simple force balance. (A) The free body diagram of forces at each edge of the blastoderm margin. Red arrows indicate a constant driving tangential force, FTan. Blue arrows indicate the force generated by CCT. The vectors FTan and FCCT form the angle θ. (See also Fig. S4 and Movies S2 and S3.) (B) The projection of FCCT (blue arrows) adds to FTan on the right edge and counteracts FTan on the left edge, creating a larger net force at the right edge of the blastoderm margin (purple arrows). (C) Experimental data shown in blue are Δv and Δcosθ calculated at 30 min intervals between 30% and 80% epiboly in 16 embryos. A seven-point moving average is shown in green to indicate the overall trend. A linear fit of Δv versus Δcosθ is shown in red (R2 – 0.12), which yields a slope of 23 ± 6 nm s−1 (p-value < 0.001 equivalent to 0 nm s−1) and intercept of 0.30 ± 1.56 nm s−1, with uncertainties determined based on the least-squares fit of the raw data (blue) to a line (red). E2(+): E2 medium including 1 mM Ca2+.

Force-balance models recapitulate blastoderm reorientation in asymmetric embryos

We developed both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) models of blastoderm migration on an asymmetric yolk (Fig. 3, A and B, Supporting Material, Figs. S4 and S5, and Movies S2 and S3). Since both models generate essentially the same results, we present the 2D model here because it is more concise. As mentioned previously, there are two main forces present during epiboly, a tangential force along the surface of the embryo, FTan, and the force resulting from CCT, FCCT, which is directed toward the geometric center of the actin band. The net force on the edge of the blastoderm margin, FNet, can be related to an observed cell migration velocity, v, by introducing a drag coefficient, cDrag, that arises from cell-cell, cell-yolk, and in our case blastoderm-agarose interactions (22–24). In 2D, a simple relationship relates FCCT and FTan to the migration velocity observed on the left and right sides of the embryo as seen in cross section (Fig. 3 B):

| (1) |

| (2) |

These equations predict that Δv, the difference in velocities of the leading and lagging edges of the blastoderm margin, is

| (3) |

| (4) |

In unperturbed, symmetric embryos (Δcosθ = 0), the blastoderm margin spreads uniformly (Δv = 0), suggesting that the tangential force is also uniform (ΔFTan = 0). In principle, the nonzero Δv in shape-perturbed embryos could result from differences in local force production (ΔFTan ≠ 0) resulting from some form of biochemical feedback. However, as will be shown, the more parsimonious assumption that ΔFTan = 0 in both unperturbed and compressed embryos is sufficient to account for the data. Under the simplifying assumption that the FTan is uniform along the embryo, equation 4 simplifies to:

| (5) |

Importantly, equation 5 reproduces the linear relationship between Δv and Δcosθ observed for a wide variety of embryo shapes (Fig. 3). The physical interpretation is that CCT provides a supplemental force that is sensitive to local asymmetries in the embryo, and that speeds up the lagging edge of the embryo while simultaneously slowing down the leading edge. As a result, the blastoderm reorients toward the imposed long axis. Equation 5 also predicts that the blastoderm in symmetric embryos should spread uniformly (Δv and Δcosθ = 0), as is in fact observed. The unconstrained linear fit for Δv vs. Δcos θ returns an intercept value that was close to zero (Table S1), consistent with the idea that a simple force balance is sufficient to account for the rate of blastoderm migration in both unperturbed and asymmetric embryos.

Chemical disruption of CCT leads to uniform blastoderm margin migration velocity

A consequence of our model (Equation 5) is the prediction that abrogating CCT should prevent reorientation. Previous studies show that altering Ca2+ concentration in the surrounding media provides an effective mechanism to modulate CCT: the actin band does not form when Ca2+ is sequestered from the embryo growth media by EGTA or BAPTA (7), while increased extracellular Ca2+ results in an oblong embryo phenotype consistent with increased actin band contractility (8). Importantly, we observe that development proceeds normally through 16 h (completion of epiboly), at all of the Ca2+ concentrations greater than or equal to 62.5 μM, demonstrating that Ca2+ reduction is a suitable method for targeted disruption of CCT.

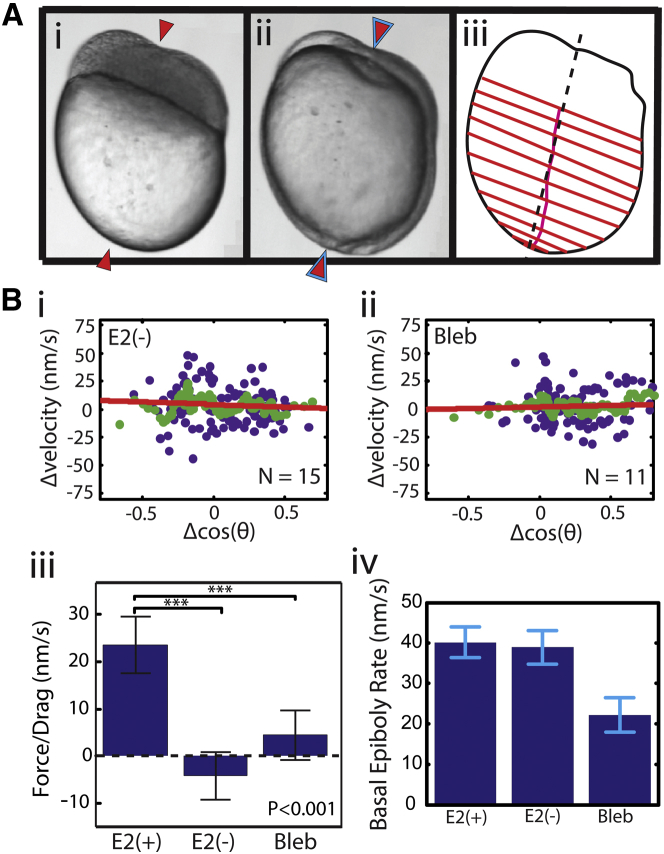

We find that blastoderm reorientation does not occur in reduced, 62.5 μM Ca2+ media (Δv ≈ 0), regardless of embryo geometry (Figs. 4 and S6). Moreover, the overall rate of epiboly of embryos grown in reduced Ca2+ media is not statistically different from that observed in E2 media, indicating that the FTan is essentially unaltered under these conditions (Fig. S4 B). These results could, in principle, imply that changes in ΔFTan perfectly cancel the asymmetric contributions of FCCT specifically in reduced-Ca2+ media. However, a simpler explanation is that ΔFTan and FCCT are both close to zero under these conditions, in support of the initial assumption that FTan is uniform about the blastoderm margin.

Figure 4.

Disrupting CCT eliminates differential blastoderm migration and eliminates axis realignment. (A) An asymmetric embryo grown in reduced, 62.5 μM Ca2+ media. (i) The initial blastoderm mass defines the AV axis (red arrows). (ii) The location of blastopore closure and eventual AP axis (blue arrows) coincide with the initial AV axis (red arrows). (iii) The migration pattern of the blastoderm shows nearly uniform migration (red parallel lines) over the course of epiboly. Consequently, migration of the center of the blastoderm margin (magenta transverse line) lies very near the AV axis (dashed black line; cf. Fig. 1C). (B) (i and ii) Quantification of the CCT force which is equivalent to the slope of the linear fit. The slope of the linear fit is statistically equivalent to 0 when CCT is disrupted by lowering Ca2+ to 62.5 μM (i; E2(−), −4 ± 5 nm s−1, R2 – 0.005, p-value = 0.82) or by introducing 13.8 μM blebbistatin (ii; Bleb, 3 ± 5 nm s−1, R2 – 0.003, p-value = 0.56). (iii) FCCT/cDrag is statistically significantly lower (∗∗∗p < 0.001) in embryos grown in E2(−) media or with introduced blebbistatin compared to embryos grown in E2(+) media. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the slope of the fit as described in Fig. 3C. (iv) Overall rates of epiboly in E2(+), E2(−), and E2 with 13.8 μM blebbistatin. The overall rate of epiboly in E2(−) is statistically equivalent to that observed in E2(+), whereas introduction of blebbistatin severely delays epiboly. The rates of epiboly reflect the mean ± SD of the average rate of epiboly over multiple embryos (16 for E2(+), 15 for E2(−), and 11 for Bleb). (See also Fig. S6, Movies S4 and S5, and Table S1 for more detailed fit parameters.)

The myosin inhibitor blebbistatin also decreases CCT as measured using laser microdissection (5). However, blebbistatin additionally reduces the rate of myosin flow toward the actin band, which results in a reduction in the force that drives epiboly (5). Consequently, blebbistatin likely decreases both CCT and FTan. We added 13.8 μM blebbistatin to compressed embryos and quantified both the rate of epiboly and blastoderm reorientation, as before. We found that, as in reduced-Ca2+ media, Δv ≈ 0 (Fig. 4 B). In addition, we noted that the addition of blebbistatin resulted in severely delayed epiboly (Fig. 4 B), consistent with a role for actomyosin flow in generating force that contributes to FTan (5).

In summary, reduction of CCT with either reduced Ca2+ media or the addition of blebbistatin blocked blastoderm reorientation in a dose-dependent manner, and essentially abolished the positive correlation between Δv and Δcos θ while maintaining an intercept that is close to zero (Figs. 4 and S6; Movies S4 and S5 and Table S1). Further, the spatially uniform rate of blastoderm migration observed under these conditions implies that FTan is close to uniform. These results collectively implicate CCT as the principal mechanism responsible for blastoderm reorientation.

FCCT is comparable in magnitude to FTan

While it is not experimentally feasible to directly measure either FTan or FCCT, we can estimate their relative magnitudes. The overall rate of epiboly, 40 ± 4 nm s−1, provides an approximate measure of FTan/cDrag. The slope of Δv/Δcosθ likewise yields FCCT/cDrag = 23 ± 6 nm s−1 (Fig. 3 C). Thus, FTan/cDrag and FCCT/cDrag are comparable in magnitude, strongly suggesting that CCT significantly affects cell movements during epiboly. This result is intuitively consistent with the observation that CCT visibly distorts the shape of the embryo during epiboly.

We used experimentally obtained values of FCCT/cDrag to simulate blastoderm migration in shape-perturbed embryos grown either in E2 media, E2 with reduced Ca2+ (62.5 μM), or E2 with blebbistatin (13.8 μM) (Fig. 4). FCCT/cDrag values of 23 nm s−1 (normal E2 media) and 0 nm s−1 (reduced Ca2+ or blebbistatin) correctly predict the location of the blastoderm edges for embryos of different geometries (Fig. S7 and Movies S4 and S5). The agreement between our simulation and experimental results under a range of mechanical and molecular perturbations reinforces the argument that reorientation is principally a function of CCT.

Extracellular calcium regulates coordinated cell migration at the blastoderm margin

We hypothesized that CCT, in addition to globally coordinating the blastoderm margin during epiboly, might coordinate the movement of neighboring cells. Previous results have shown that migrating epithelial sheets commonly exhibit finger-like protrusions caused by local variations in migration velocity (3). In contrast, the blastoderm margin maintains a smooth boundary throughout epiboly (Fig. 5 A). We therefore imaged the actin cytoskeleton of enveloping layer cells in fixed embryos between 55% and 60% epiboly using TMR-phalloidin. Reduced Ca2+ media (62.5 μm) was used to selectively disrupt CCT (Fig. S2 and Movie S6). (Blebbistatin reduces both CCT and the tangential force, FTan, and would therefore be expected to decrease both the forces leading to (FTan) and resisting (FCCT) the formation of instabilities.)

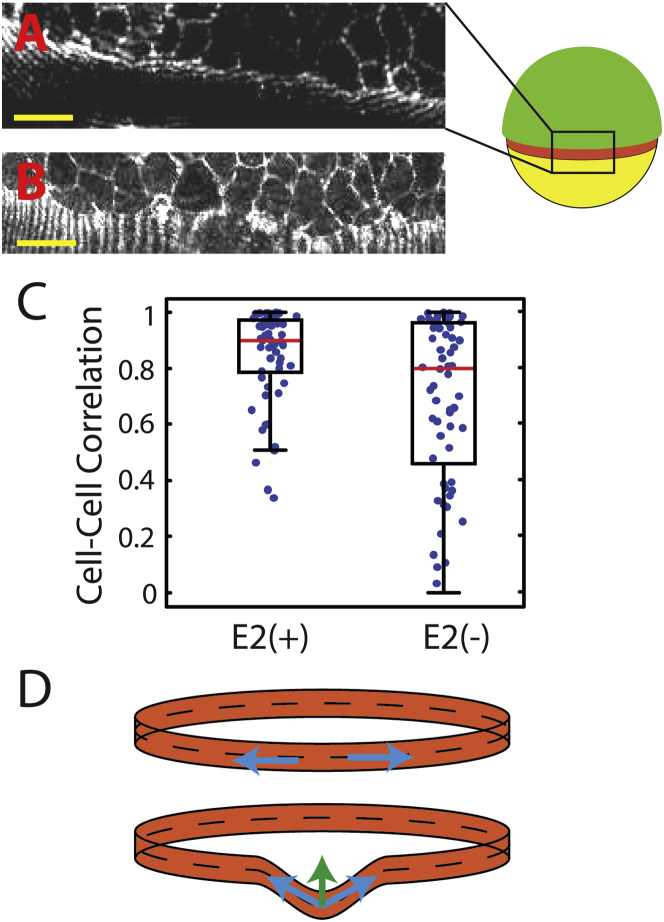

Figure 5.

Reduction of CCT in E2(−) media reduces the coordination of neighboring cells at the blastoderm margin. (A and B) View of the blastoderm margin in TMR-phalloidin-stained embryos fixed at 60% epiboly after developing in E2(+) (A) or E2(−) (B). Cell-to-cell coordination is markedly reduced in low Ca2+ media. The apparent striations in (A) and (B) result from finite slice spacing in the confocal images (see also Fig. S2 and Movie S6). (C) The distribution of cell-cell correlation vectors shows a statistically significant increase in margin roughness for embryos grown in E2(−). Red line, mean; box, first and third quartiles; whiskers, 2.7 standard deviations. (D) Schematic of tension along the blastoderm margin. Tension (blue arrows) generates a net restorative force (green arrow) against local perturbations. Scale bars, 40 μm.

In embryos grown in normal E2, we observe that the cells form a smooth margin (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, embryos grown in reduced-Ca2+ media exhibit noticeably more disorder along the blastoderm margin (Fig. 5 B). We quantified the blastoderm margin roughness by measuring the correlation vector between adjacent cells (Figs. 5 C and S2). We use this metric as opposed to measuring the roughness of the membrane boundary to avoid quantifying instabilities influenced by cell morphology. Cell-cell vectors are more correlated for embryos grown in normal E2 versus E2 with reduced Ca2+ (0.82 vs. 0.69; P < 0.01, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). It is important to note that the variance in cell-cell angles is likewise lower for embryos grown in normal E2 versus reduced-Ca2+ E2 (0.040 vs. 0.082; P < 0.0001, F-test). These observations show that the marginal cells in embryos grown in normal E2 are highly aligned, and that disruption of CCT via Ca2+ depletion corresponds to a decrease in cell-cell coordination. This increased misalignment supports the hypothesis that tension within the actin band coordinates cell migration throughout the blastoderm margin (Fig. 5 D).

The AP and AV axes are not synonymous in zebrafish

A question remains as to whether the mechanical forces generated by the actin band have an effect on overall zebrafish development, for example, in axis formation. Previous studies have reported that the AP axis forms along the AV axis, but it was unclear whether this is truly the case or whether the two axes are functionally distinct but overlapping (Fig. 2 I) (25–27). In compressed embryos grown in E2 media, we observe, for the first time to our knowledge, formation of the AP axis of the zebrafish, as indicated by the location of converging cells that form the head and tail (Fig. 2 E, blue arrows), which is decoupled from the initial AV axis (Fig. 2 E, red arrows). In these embryos, the AP axis shifts toward the imposed long axis of the embryo. To test whether the shift in AP axis was due to the symmetry of the embryo or instead resulted from nonuniform cell migration due to FCCT, we monitored development in compressed embryos grown in reduced-Ca2+ media. We observe that under these conditions the posterior end forms near the site of the vegetal pole (Fig. 4 A). We therefore conclude that the AP axis is specified by the site of blastopore closure and is distinct from the AV axis.

Discussion

Until recently, the prevailing hypothesis concerning the role of CCT was that it helped drive epiboly movements past 50% by constricting the blastoderm margin (8). However, a recent study suggested that actomyosin flow, independent of CCT, generates sufficient force to drive epiboly (5). This view of epiboly is supported by our observation that disruption of the actin band in low-Ca2+ media does not result in epibolic arrest. Previous experiments targeting CCT using chemical perturbations such as blebbistatin may have arrested epiboly not by eliminating CCT in its role as a supplementary force, but instead by inhibiting flow friction, an explanation supported by our observation that blebbistatin prevents epiboly from completing, whereas decreased Ca2+ does not (7,28,29).

Our data support a model in which tension within the actin band coordinates cell migration along the blastoderm margin on both global and local scales. Alternate mechanisms, for example, relocalization of actin and myosin to generate greater tangential force on one side of the embryo, could in principal drive reorientation. Additional factors such as cell adhesion (19,28), cell differentiation (8,17,18,30,31), and convergent extension movements (4,32) may also influence the rate and geometry of epiboly. However, a physical model based on CCT (Eq. 5) is sufficient to quantitatively account for the rate and extent of blastoderm reorientation under a broad range of experimental conditions. In the absence of additional data necessitating a more complex model, we thus prefer the minimalistic mechanism proposed here.

According to Eq. 5, tension within the actin band pulls unequally on the edges of the blastoderm of an asymmetric embryo, speeding the migration of the trailing edge and slowing the leading edge. In addition, CCT generates a restoring force against perturbations that might otherwise develop along the margin, thus preventing local instabilities analogous to the finger-like patterns observed during in vitro epithelial spreading (3). Decreasing the tension in the actin band either via low Ca2+ or added blebbistatin relaxes the CCT rubber band. As a result, both the leading and trailing sides of the blastoderm margin move at the same rates. Disruption of the actin band additionally results in spontaneous disorder among the marginal cells, again suggesting that CCT helps maintain cell-cell coordination. It is important to note that the force generated by CCT does not stall epiboly, since the experimentally determined maximal CCT contribution (23 ± 6 nm s−1) is less than that of the overall epiboly rate (40 ± 4 nm s−1).

A consequence of nonuniform blastoderm migration in asymmetric embryos is that the AP and AV axes are not equivalent, which has been a subject of discussion in understanding zebrafish axis specification (25,26). Our results support the hypothesis that the AP axis is established via migration patterns that determine the location of blastopore closure, a distinction that would be difficult to make in a symmetric embryo. Signals such as FGF and retinoic acid control the spatial expression of genes specifying anterior and posterior fates, and moreover coincide with the location of the blastoderm margin during epiboly (33). Recent results suggest in addition that the specification of the AP and dorsoventral (DV) axes are intimately coordinated, and occur in the same time frame as epiboly (34). Mechanical reorientation of the margin may thus lead to a redistribution of posteriorizing factors, providing an appealing mechanism that links mechanical and chemical patterning.

Little is currently known about how cell migration is coordinated across distances that are large relative to individual cells (35–39). Our study introduces a proposed role for CCT generated by the actin band in coordinating cell movements during epiboly. Analogous contractile actin bands are also observed during wound healing (9,10) and during dorsal closure in Drosophila embryos (11–13). We speculate that tension generated at the margin of cell sheets may thus provide a general means of coordinating cell movements in a wide variety of developmental and physiological processes. This link between mechanics and morphogenesis complements recent results demonstrating that mechanical signals can alter morphogenesis in both Drosophila and mouse embryos (35,36,40,41).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Philippe Mourrain for assistance with zebrafish husbandry and Dr. William Talbot for helpful discussions. We further acknowledge the Zebrafish International Resource Center for providing us with wild-type and transgenic fish lines and the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for access to confocal imaging.

This work was funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship (J.C.), a Stanford Cardiovascular Institute Younger Award (J.C.), a Stanford Graduate Fellowship (A.L.H.), a Human Frontier Science Program Longterm Fellowship (M.K.), a Stanford Bio-X Fellowship (C.D.B.), NSF Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation grant 1135790 (A.R.D.), National Institutes of Health New Innovator Award 1DP2OD007078-01 (A.R.D.), and a Burroughs-Wellcome Career Award at the Scientific Interface (A.R.D.) The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Editor: Rong Li.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Supporting Materials and Methods, seven figures, one table, and six movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(15)00410-5.

Supporting Material

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model incorporating the FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that incorporates CCT (blue) contribution better predicts the edges. Related to Fig. 2.

(Left) At each marginal ring, a uniform tangential force (red) is generated around the ring directed along the tangent of the ellipsoid while a force due to CCT (green) is generated around the ring and points toward its center. (Middle) Due to the uneven contribution of CCT (green), on the left side, CCT projects negatively onto the tangent, whereas on the right side CCT projects positively onto the tangent. Combining this with the uniform tangential force results in an uneven net tangential force. (Right, maroon). Consequently, over the course of the model, the right side of the ring progresses faster on the right side than on the left side, resulting in reorientation of the ring perpendicular to the long axis of the ellipsoid. Related to Fig. 3.

(Left) CCT (green) produces a uniform force around the ring along with a uniform tangent force (red). Since the ring is symmetric, CCT provides an equal contribution of force to the tangent at each point on the ring, causing uniform net tangential force (right, maroon). Consequently, the ring progresses uniformly down both the ellipsoid and the sphere. Related to Fig. 3.

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model incorporating a FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that lacks CCT (red) better predicts the position of the blastoderm margin edges. Related to Fig. 4.

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model that incorporates an FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that lacks CCT (red) better predicts the edges. Related to Fig. 4.

In both cases, the embryos develop properly through the conclusion of epiboly. Related to Fig. 5.

References

- 1.Aman A., Piotrowski T. Cell migration during morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2010;341:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedl P., Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trepat X., Wasserman M.R., Fredberg J.J. Physical forces during collective cell migration. Nat. Phys. 2009;5:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schier A.F., Talbot W.S. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrndt M., Salbreux G., Heisenberg C.P. Forces driving epithelial spreading in zebrafish gastrulation. Science. 2012;338:257–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1224143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho L., Heisenberg C.P. The yolk syncytial layer in early zebrafish development. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng J.C., Miller A.L., Webb S.E. Organization and function of microfilaments during late epiboly in zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 2004;231:313–323. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloway B.A., Gomez de la Torre Canny S., Mullins M.C. A novel role for MAPKAPK2 in morphogenesis during zebrafish development. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danjo Y., Gipson I.K. Actin “purse string” filaments are anchored by E-cadherin-mediated adherens junctions at the leading edge of the epithelial wound, providing coordinated cell movement. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:3323–3332. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.22.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamada M., Perez T.D., Sheetz M.P. Two distinct modes of myosin assembly and dynamics during epithelial wound closure. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antunes M., Pereira T., Jacinto A. Coordinated waves of actomyosin flow and apical cell constriction immediately after wounding. J. Cell Biol. 2013;202:365–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacinto A., Wood W., Martin P. Dynamic analysis of actin cable function during Drosophila dorsal closure. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiehart D.P., Galbraith C.G., Montague R.A. Multiple forces contribute to cell sheet morphogenesis for dorsal closure in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:471–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wühr M., Tan E.S., Mitchison T.J. A model for cleavage plane determination in early amphibian and fish embryos. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:2040–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonneau B., Popgeorgiev N., Gillet G. Cytoskeleton dynamics in early zebrafish development: a matter of phosphorylation? BioArchitecture. 2011;1:216–220. doi: 10.4161/bioa.18116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solnica-Krezel L., Driever W. Microtubule arrays of the zebrafish yolk cell: organization and function during epiboly. Development. 1994;120:2443–2455. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strähle U., Jesuthasan S. Ultraviolet irradiation impairs epiboly in zebrafish embryos: evidence for a microtubule-dependent mechanism of epiboly. Development. 1993;119:909–919. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babb S.G., Marrs J.A. E-cadherin regulates cell movements and tissue formation in early zebrafish embryos. Dev. Dyn. 2004;230:263–277. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song S., Eckerle S., Driever W. Pou5f1-dependent EGF expression controls E-cadherin endocytosis, cell adhesion, and zebrafish epiboly movements. Dev. Cell. 2013;24:486–501. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning M.L., Foty R.A., Schoetz E.M. Coaction of intercellular adhesion and cortical tension specifies tissue surface tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12517–12522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokes C.L., Lauffenburger D.A., Williams S.K. Migration of individual microvessel endothelial cells: stochastic model and parameter measurement. J. Cell Sci. 1991;99:419–430. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitorino P., Meyer T. Modular control of endothelial sheet migration. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3268–3281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1725808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamao M., Naoki H., Ishii S. Multi-cellular logistics of collective cell migration. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerhart J. Changing the axis changes the perspective. Dev. Dyn. 2002;225:380–383. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinhardt H. Primary body axes of vertebrates: generation of a near-Cartesian coordinate system and the role of Spemann-type organizer. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:2907–2919. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varga M., Maegawa S., Weinberg E.S. Correct anteroposterior patterning of the zebrafish neurectoderm in the absence of the early dorsal organizer. BMC Dev. Biol. 2011;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zalik S.E., Lewandowski E., Geiger B. Cell adhesion and the actin cytoskeleton of the enveloping layer in the zebrafish embryo during epiboly. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999;77:527–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Köppen M., Fernández B.G., Heisenberg C.P. Coordinated cell-shape changes control epithelial movement in zebrafish and Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2671–2681. doi: 10.1242/dev.02439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherdantseva E.M., Cherdantsev V.G. Geometry and mechanics of teleost gastrulation and the formation of primary embryonic axes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2006;50:157–168. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052059ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dick A., Hild M., Hammerschmidt M. Essential role of Bmp7 (snailhouse) and its prodomain in dorsoventral patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2000;127:343–354. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warga R.M., Kimmel C.B. Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish. Development. 1990;108:569–580. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudoh T., Wilson S.W., Dawid I.B. Distinct roles for Fgf, Wnt and retinoic acid in posteriorizing the neural ectoderm. Development. 2002;129:4335–4346. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashiguchi M., Mullins M.C. Anteroposterior and dorsoventral patterning are coordinated by an identical patterning clock. Development. 2013;140:1970–1980. doi: 10.1242/dev.088104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desprat N., Supatto W., Farge E. Tissue deformation modulates twist expression to determine anterior midgut differentiation in Drosophila embryos. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farge E. Mechanical induction of Twist in the Drosophila foregut/stomodeal primordium. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1365–1377. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson L.A., Marsden M., DeSimone D.W. Integrin α5β1 and fibronectin regulate polarized cell protrusions required for Xenopus convergence and extension. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsden M., DeSimone D.W. Integrin-ECM interactions regulate cadherin-dependent cell adhesion and are required for convergent extension in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller R. Cell migration during gastrulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:533–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brouzés E., Supatto W., Farge E. Is mechano-sensitive expression of twist involved in mesoderm formation? Biol. Cell. 2004;96:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiramatsu R., Matsuoka T., Matsuo I. External mechanical cues trigger the establishment of the anterior-posterior axis in early mouse embryos. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model incorporating the FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that incorporates CCT (blue) contribution better predicts the edges. Related to Fig. 2.

(Left) At each marginal ring, a uniform tangential force (red) is generated around the ring directed along the tangent of the ellipsoid while a force due to CCT (green) is generated around the ring and points toward its center. (Middle) Due to the uneven contribution of CCT (green), on the left side, CCT projects negatively onto the tangent, whereas on the right side CCT projects positively onto the tangent. Combining this with the uniform tangential force results in an uneven net tangential force. (Right, maroon). Consequently, over the course of the model, the right side of the ring progresses faster on the right side than on the left side, resulting in reorientation of the ring perpendicular to the long axis of the ellipsoid. Related to Fig. 3.

(Left) CCT (green) produces a uniform force around the ring along with a uniform tangent force (red). Since the ring is symmetric, CCT provides an equal contribution of force to the tangent at each point on the ring, causing uniform net tangential force (right, maroon). Consequently, the ring progresses uniformly down both the ellipsoid and the sphere. Related to Fig. 3.

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model incorporating a FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that lacks CCT (red) better predicts the position of the blastoderm margin edges. Related to Fig. 4.

Blue lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model that incorporates an FCCT/cDrag value of 28 nm s−1. Red lines indicate the predicted edges of epiboly using a model without CCT incorporated. Over the course of epiboly, the model that lacks CCT (red) better predicts the edges. Related to Fig. 4.

In both cases, the embryos develop properly through the conclusion of epiboly. Related to Fig. 5.