Abstract

Background:

Treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with antidepressants might be of utility to improve patient's condition. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of Duloxetine on depression, anxiety, severity of symptoms, and quality of life (QOL) in IBD patients.

Materials and Methods:

In a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial on 2013-2014, in Alzahra Hospital (Isfahan, Iran), 44 IBD patients were chosen to receive either duloxetine (60 mg/day) or placebo. They were treated in a 12 weeks program, and all of the participants also received mesalazine, 2-4 g daily. We assessed anxiety and depression with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the severity of symptoms with Lichtiger Colitis Activity Index and QOL with World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments, before and just after the treatment. The data were analyzed using Paired sample t-test and ANCOVA.

Results:

In 35 subjects who completed the study, the mean (standard error [SE]) scores of depression and anxiety were reduced in duloxetine more than placebo group, significantly (P = 0.041 and P = 0.049, respectively). The mean (SE) scores of severity of symptom were also reduced in duloxetine more than the placebo group, significantly (P = 0.02). The mean (SE) scores of physical, psychological, and social dimensions of QOL were increased after treatment with duloxetine more than placebo group, significantly (P = 0.001, P = 0.038, and P = 0.015, respectively). The environmental QOL was not increased significantly (P = 0.260).

Conclusion:

Duloxetine is probably effective and safe for reducing depression, anxiety and severity of physical symptoms. It also could increase physical, psychological, and social QOL in patients.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, duloxetine, inflammatory bowel disease, quality of life, symptom severity

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic disease described by the improper immune response which causes inflammatory lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. The etiology of the disease is unknown. However, environmental, immune, and genetic factors have all been involved in its occurrence.[1,2] The course of IBD is unpredictable. In the course of the disease, different signs and symptoms are seen, and drug side effects and complications of IBD are various. Interestingly, Psychological status has been found to impact the course of the disease.[3,4] There is an important pathophysiological relations and common pathways between some psychiatric disorders such as anxiety or depression and IBD, which is related to impaired function of immunoregulatory circuits.[5,6,7,8] Clinical studies shows that many of the patients experience depression and anxiety that is much more compared with a healthy population.[9] The rate of depression during remission is about 30%, and the rate of depression and anxiety during relapse is about 70% and 80%, respectively.[10,11,12] Depression has a great influence on disease severity and cause a greater possibility of earlier or more frequent relapses.[10]

On the other hand, many of these patients suffer from pain, fatigue, and physical disablement which cause poor quality of life (QOL). As well as depression and anxiety, poor QOL is a predictor of unfavorable medical outcomes, and psychological status also has an independent effect on QOL.[10,13,14] In fact, those subjects who have both psychological disorders and IBD have more frequent relapses and lower QOL.[10,15,16]

Depression and anxiety are treatable conditions. The most used treatments are psychological interventions such as cognitive behavior therapies and pharmacological treatments especially the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).[17,18,19] On the other hand, it has been shown that antidepressants have effects on production of some pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-4, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α.[20] Therefore, there is a possibility that antidepressants not only help with depression and anxiety but also positively influence the course of the disease.[12] Clinical studies for psychological interventions have recently been conducted, but antidepressants have not been studied in the IBD patients widely.[21]

Some studies have suggested that treating patients with antidepressants might be of utility to control disease severity, increase QOL and lengthen remission; but in humans, although it has been shown that antidepressants improve both somatic and mental status of patients, the low quantity and quality of available clinical studies cause significant limits to making a decisive statement on their efficacy.[11,12]

Thus, it is obvious that more randomized controlled trials are needed to provide the decisive answer on the antidepressants efficacy in IBD patients. Some clinicians have indicated that use of SNRIs (e.g., duloxetine and venlafaxine) may be more effective than SSRIs in patients with IBD,[22] and based on this we decided to assess efficacy of duloxetine on anxiety, depression, severity of symptoms and QOL in patients with IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This study is a randomized, double-blind controlled clinical trial with an active medication condition (duloxetine) and a matching placebo, which was carried out on 2013-2014. It has been registered on Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials with identifier Number IRCT201411127841N8. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki on Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects and was approved by the Ethics Committee from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (No: 392319). All participants provided written informed consent.

Subjects were chosen from IBD patients (UCs and CD) who referred to the gastrointestinal clinic of Alzahra Hospital (Isfahan, Iran) by other physicians and specialty services for the treatment of IBD as a routine program. The patients were admitted to the outpatient clinic, and the diagnosis of IBD was made by comprehensive physical examination, serologic examination, imaging studies, endoscopy, and biopsies, and finally excluding other causes.[23]

All subjects met the following inclusion criteria:

18-65 years aged;

Current diagnosis of IBD;[23]

Having no flair up of disease through past 6 months;

Willing and able to comply with study procedures; and

Willing and able to provide written informed consent.

Subjects also met none of the following unmet criteria:

Any serious medical condition that may interfere with safe study participation;

Current lactation, pregnancy or inadequate contraception;

Current serious suicidal intention or plan;

Lifetime bipolar, psychotic, or obsessive-compulsive disorder;

Substance use disorders, major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders in the past 6 months;

Treatment with any psychotropic medication within 7 days (or five medication half-lives) before study.

A total of 62 individuals screened. At the screening visit, after providing demographic data, subjects received physical examination, electrocardiography (EKG), liver function tests (i.e., aspartate transaminase [AST] and alanine transaminase [ALT]), and urine pregnancy test to ensure that the results did not preclude involving in the study. Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.[24]

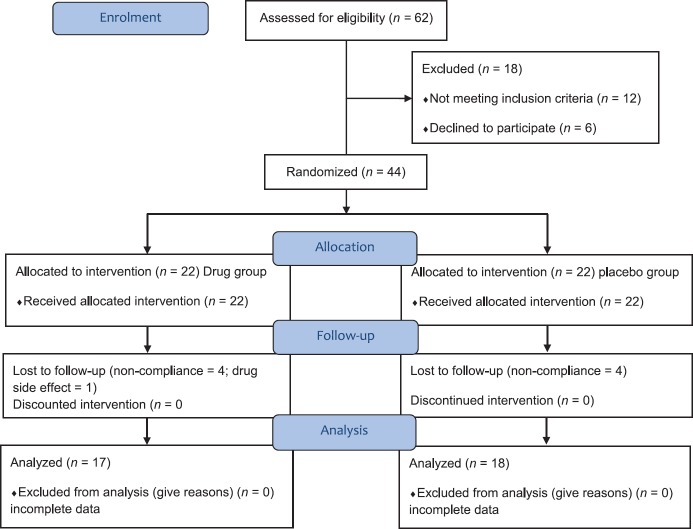

Finally, 44 subjects met all inclusion and no unmet criteria. Eligible subjects were allocated to two groups and received either of duloxetine (a) or placebo (b), with simple randomization by a third party physician using tables of random numbers. Nine patients dropped out in the study process; one patient in duloxetine group because of drug side effect (nausea), and others because of noncompliance [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Consort statement

Procedures and variables assessment

The study was performed in 12 weeks. In the drug group, duloxetine (Iran Daru, Iran), started with 30 mg once a day for 1-week, and then 60 mg once a day for the next 11 weeks. Subjects who were unable to tolerate 60 mg daily were excluded from the study. In the placebo group, the subjects received placebo in the same form and packages as duloxetine which was prepared in School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Participants were dispensed 1-or 2-week supply of medication in blister packages and instructed in how to self-use the medication at home. Subjects were visited in the outpatient gastrointestinal clinic weekly for the first 4 weeks and then every other week for assessing the compliance and drug side effects and supplying the subjects with drugs. They were asked to bring the drug packets to the clinic at each visit for pill counts to monitor the adherence. All of the subjects were also treated with mesalazine, 2-4 g daily.

We assessed anxiety, depression, the severity of symptoms, and QOL in subjects before and just after the treatment. Anxiety and depression were assessed with The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). HADS is a well-performed and widely used questionnaire to measure psychological distress in both psychological and somatic patients. It is sensitive to response to both psychological and interventions and during the course of the disease. The HADS consists of 14 items (7 item for anxiety and 7 item for depression), rating in each item are based on a 4-point scale, with maximum scores of 21 for depression and anxiety.[25] We used the validated Persian version of this questionnaire. The internal consistency of it, as measured by the Cronbach's alpha coefficient has been found to be 0.78 for the anxiety sub-scale and 0.86 for the depression sub-scale indicating a satisfactory reliability.[26] The severity of symptoms was assessed with Lichtiger Colitis Activity Index (LCAI). LCAI consists of 8 items and rating in each item is different according to the type of question. The score is ranged from 0 to 21.[27] The QOL in subjects was assessed by World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF). WHOQOL-BREF is an abbreviated generic QOL scale developed through the WHO. It is a short form WHOQOL-100 and provides a reliable and valid alternative to the assessment of the subject QOL in the last 2 weeks. WHOQOL-BREF is useful in studies that require a brief assessment of QOL and evaluation of treatment efficacy. It is consisted of four domains including physical, psychological, social, and environment.[28,29] The translation and back-translation method were used to prepare the Persian translation of LCAI and WHOQOL-BREF questioners. Questioners were translated by two physicians to Persian and then two other bilingual physicians translated the same text to the first language. Translated texts were evaluated by the translation team for a final decision.[30]

Blinding

Randomization was done by a third party physician using tables of random numbers. Questioner scores were assessed by a psychologist who was not informed about grouping of the subjects.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, independent t-test and Mann-Whitney test for demographic and clinical differences between two groups; Fisher's exact test was used for analysis of side effect differences between two groups. We used paired sample t-test and ANCOVA for analyzing of within and between group differences. The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and a P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline profile

Thirty-five patients completed the study. These subjects all had the normal range of EKG, liver function tests (i.e., AST and ALT), and physical examination at the beginning. The mean (standard error [SE]) age was 38 (8.08) years, ranging from 26 to 54 years old. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) years of disease duration were 6.49 (3.27), ranging from 2 to 15 years. There was 16 (45.7%) male and 19 (54.3%) female. The mean (SD) score of depression and anxiety in subjects were 9.22 (3.45) and 8.17 (4.29), respectively.

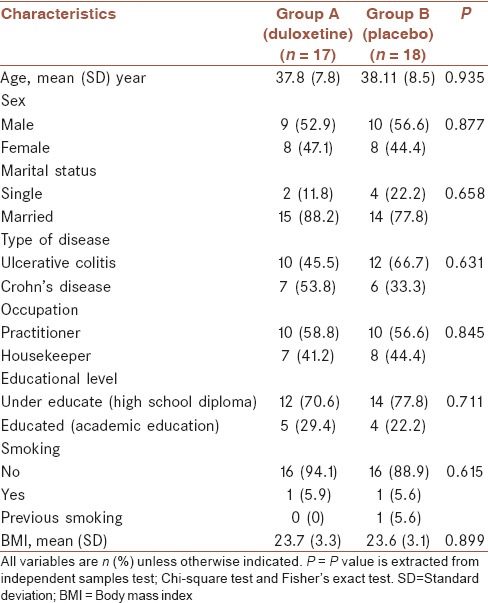

Comparison of baseline profile of subjects, including age, sex, marital status, occupation, educational level, type of disease, body mass index, and smoking revealed no statistically significant differences between two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of subjects (n = 35)

The mean (SD) years of disease duration were 6.24 (3.45) in Group A and 6.72 (3.17) in Group B. Mann-Whitney test, showed that the difference was not significant (P = 0.538).

Outcomes

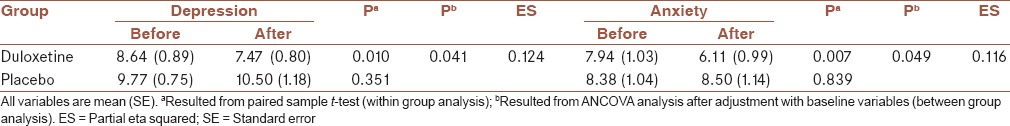

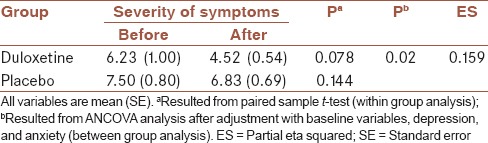

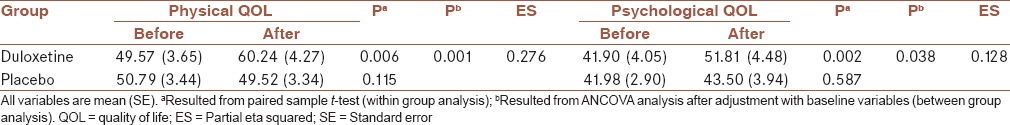

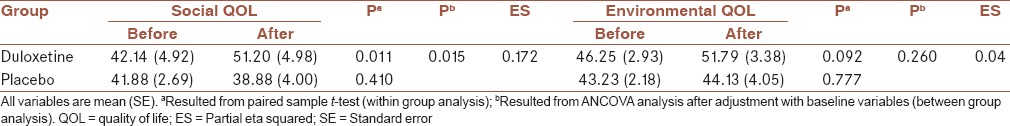

After treatment, in the duloxetine group, the mean scores were decreased for depression, anxiety, and severity of symptoms significantly [Tables 2 and 3]. Also, physical, psychological, and social QOL were increased after treatment significantly. Environmental QOL was increased but not significantly (0.092) [Tables 4 and 5]. In the placebo group, the changes in mean scores were not significant for depression, anxiety, severity of symptoms, and four dimensions of QOL after treatment [Tables 2–5].

Table 2.

Within-group and between-group analysis for depression and anxiety in two groups

Table 3.

Within-group and between group analysis for severity of symptoms in two group

Table 4.

Within group and between group analysis for physical and psychological QOL in two group

Table 5.

Within-group and between-group analysis for social and environmental QOL in two group

After adjustment with baseline variables, between-group analyses showed that depression and anxiety were decreased in the duloxetine in compare to the placebo group, significantly (P = 0.041 and 0.049, respectively) [Table 2]. Between-group analyses also showed that severity of symptoms was decreased in the duloxetine in compare to placebo group, significantly (P = 0.02), after adjustment with baseline variables and also depression and anxiety severity [Table 3].

Comparing the dimensions of QOL between two groups showed that physical, psychological, and social QOL were increased after treatment in duloxetine group more than placebo group significantly (P = 0.001, 0.038 and 0.015, respectively). After treatment, the changes in the environmental QOL was not different between two groups, significantly (P = 0.26) [Tables 4 and 5].

The effect size of duloxetine for different parameters, including depression, anxiety, severity of symptoms, and QOL was mild to moderate.

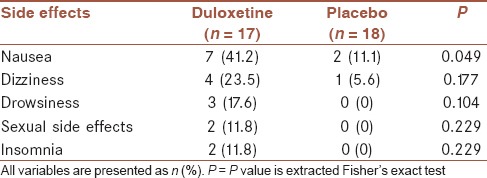

Tolerability and side effects

The reported side effects were nausea, drowsiness, dizziness, sexual side effects, and insomnia. There were 7 (41.2%) patients in duloxetine group and 2 (11.1%) patients in the placebo group with nausea, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.049). The other side effects were not different between two groups significantly [Table 6].

Table 6.

Frequency of elicited side effects of treatment

DISCUSSION

This controlled double-blinded study, assessed the efficacy of duloxetine in compare with placebo in patients with IBD. The results showed that duloxetine was effective to reduce depression, anxiety, and severity of disease symptoms and also to increase physical, psychological, and social dimensions of QOL in patients after a 12 weeks treatment.

Recent reviews have concluded that there are higher rates of depression and anxiety in IBD,[9] and our patients also had mild depression and anxiety according to the HADS questioner. Several studies had suggested that higher depression and anxiety scores are associated with the detrimental impact on disease activity, treatment response, relapses, and overall QOL.[10,13,31] Consistently, in this study, treating of patients with duloxetine, not only reduced depression and anxiety but also the severity of disease symptoms such as pain and frequency of diarrhea was decreased, and QOL was increased.

On the other hand, we know that antidepressants have anti-inflammatory properties which is done by influencing the production of cytokines with anti-inflammatory properties.[15,32] Studies in rats have shown that in models of persistent pain and nerve injury models of neuropathic pain, duloxetine has positives effects in reversing of mechanical allodynia.[33] This characteristic could contribute in duloxetine efficacy on symptoms reduction in IBD patients, because it may offer additional benefit to patients, with directly reducing inflammation. This matter needs more clinical trials in the future. In addition, recent studies have proposed an independent analgesic properties for duloxetine, which supports an advantageous treatment for patients, regardless of the presence of depression or anxiety.[34] This characteristic could cause reduction of pain in IBD patients, independent of its effect on psychological factors.

IBD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have some similarities in symptoms and other characteristics, so it is suggested that they may be two different ends of the continuum of the same condition,[35] and also there are some evidences that shows IBS can occur in context of IBD.[36] Psychological factors are considered as etiology of IBS symptoms, so antidepressants are now a part of the standard treatment for IBS and cause significant improvement in patients.[37] One previous study, on duloxetine for IBS patients showed that duloxetine was associated with improvement in pain, severity of illness, QOL, and anxiety.[38] This could be another reason for reducing of some disease symptoms with antidepressants in IBD patients, like what we resulted in our study.

Currently, antidepressants have not been greatly studied in IBD patients. Previous studies have investigated the role of antidepressants and showed that they seem to improve both somatic and mental state of patients, but these research had a low quality, and none of them was randomized controlled trials.[11,12,39] However, qualitative studies showed that physicians treat patients with antidepressants for depression, anxiety, pain, and insomnia routinely and have reported that these medications were successful in reducing gut irritability, pain and urgency of defecation.[15,40] Our study with a relatively strong method, which was controlled with matching placebo, confirmed these experiments.

QOL of IBD patients is very important because of the social consequences of the disease. In previous studies, psychological variables such as depression and anxiety and also physical symptoms such as poor bowel function and pain were negative predictive of QOL.[41] So, managing of these variables could lead to better QOL of the patients. In this study, physical, psychological, and social dimensions of QOL were increased after treatment with duloxetine. This was consistent with reducing of physical and psychological (depression and anxiety) symptoms in patients. The environmental QOL was not increased significantly.

The effect size of duloxetine was mild to moderate in our study. This could be because of a limited number of subjects, 17 patients in duloxetine group, and should be evaluated in future studies. The duloxetine was safe and tolerable in patients. No unexpected side effects were reported and in general, side effects appeared to be mild and self-limited, and often occurred during the beginning of treatment.

Limitations

This study was limited by the relatively short duration of follow-up (12 weeks) and limited sample size. It's better to evaluate the long-term efficacy of the drug in the course of disease in future trials.

CONCLUSION

Duloxetine is probably effective for reducing psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety and severity of physical symptoms such as pain in IBD patients. It also could increase the physical, psychological, and social QOL in patients. This drug may be a promising augmentation for treating IBD patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Research number 392319).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTION

HD contributed in the conception and design of the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. FN contributed in the conception of the work, conducting the study, drafting and revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. HA contributed in the conception and design of the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. MRS contributed in the conception and design of the work, conducting the study, drafting and revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. AF contributed in the conception of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. MM contributed in the conception of the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. MT contributed in the conception of the work, conducting the study, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. PA contributed in the conception of the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work. HT contributed in the conception of the work, revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript, and agreed for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We like to express our gratitude to the Psychosomatic Research Center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Isfahan, Iran) supports.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994–2002. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mawdsley JE, Macey MG, Feakins RM, Langmead L, Rampton DS. The effect of acute psychologic stress on systemic and rectal mucosal measures of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:410–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graff LA, Walker JR, Lix L, Clara I, Rawsthorne P, Rogala L, et al. The relationship of inflammatory bowel disease type and activity to psychological functioning and quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1491–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoultz M, Atherton I, Hubbard G, Watson AJ. Assessment of causal link between psychological factors and symptom exacerbation in inflammatory bowel disease: A protocol for systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Syst Rev. 2013;2:8. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipovic BR, Filipovic BF, Kerkez M, Milinic N, Randelovic T. Depression and anxiety levels in therapy-naive patients with inflammatory bowel disease and cancer of the colon. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:438–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenkranz MA. Substance P at the nexus of mind and body in chronic inflammation and affective disorders. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:1007–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rook GA, Lowry CA. The hygiene hypothesis and psychiatric disorders. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Collins SM. Impaired parasympathetic function increases susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of depression. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2209–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI32849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. It's not just about the gut: Managing depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease. Pract Gastroenterol. 2010;34:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, et al. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:79–84. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106907.24881.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke D, Gibson PR, Mikocka-Walus A. Can antidepressants influence the course of inflammatory bowel disease?. The current state of research. Eur Gastroenterol Hepatol Rev. 2009;5:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikocka-Walus AA, Gordon AL, Stewart BJ, Andrews JM. A magic pill?. A qualitative analysis of patients’ views on the role of antidepressant therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janke KH, Klump B, Gregor M, Meisner C, Haeuser W. Determinants of life satisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:272–86. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160809.38611.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yates WR, Mitchell J, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Warden D, et al. Clinical features of depressed outpatients with and without co-occurring general medical conditions in STAR*D. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. “It doesn’t do any harm, but patients feel better”: A qualitative exploratory study on gastroenterologists’ perspectives on the role of antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson K, Lööf L, Rönnblom A, Nordin K. Quality of life for patients with exacerbation in inflammatory bowel disease and how they cope with disease activity. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandelow B, Seidler-Brandler U, Becker A, Wedekind D, Rüther E. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled comparisons of psychopharmacological and psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:175–87. doi: 10.1080/15622970601110273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, van Oppen P, Andersson G. Are psychological and pharmacologic interventions equally effective in the treatment of adult depressive disorders?. A meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1675–85. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:415–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubera M, Holan V, Mathison R, Maes M. The effect of repeated amitriptyline and desipramine administration on cytokine release in C57BL/6 mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:785–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timmer A, Preiss JC, Motschall E, Rücker G, Jantschek G, Moser G. Psychological interventions for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;16:CD006913. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006913.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinath AI, Walter C, Newara MC, Szigethy EM. Pain management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Insights for the clinician. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:339–57. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12446158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menon R, Riera A, Ahmad A. A global perspective on gastrointestinal diseases. (ix).Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:427–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Ver. 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Ebrahimi M, Jarvandi S. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA, WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 11; Last cited on 2015 January]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 31.Mardini HE, Kip KE, Wilson JW. Crohn's disease: A two-year prospective study of the association between psychological distress and disease activity. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:492–7. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020509.23162.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond M, Kelly JP, Connor TJ. Antidepressants suppress production of the Th1 cytokine interferon-gamma, independent of monoamine transporter blockade. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:481–90. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iyengar S, Webster AA, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Xu JY, Simmons RM. Efficacy of duloxetine, a potent and balanced serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in persistent pain models in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:576–84. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipkovich IA, Choy EH, Van Wambeke P, Deberdt W, Sagman D. Typology of patients with fibromyalgia: Cluster analysis of duloxetine study patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiller RC. Overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):48–54. doi: 10.1159/000268121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant RV, van Langenberg DR, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: Impact on quality of life and psychological status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:916–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58:367–78. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan BP, Fogarty KV, Roberts JL, Reynolds KA, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI. Duloxetine in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: An open-label pilot study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:423–8. doi: 10.1002/hup.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. Antidepressants and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikocka-Walus AA, Gordon AL, Stewart BJ, Andrews JM. The role of antidepressants in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A short report on a clinical case-note audit. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:165–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rochelle TL, Fidler H. The importance of illness perceptions, quality of life and psychological status in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J Health Psychol. 2013;18:972–83. doi: 10.1177/1359105312459094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]