Abstract

Objective:

The objective of present study was to survey and determine the reporting standards of animal studies published during three years from 2012 to 2014 in the Indian Journal of Pharmacology (IJP).

Material and Methods:

All issues of IJP published in the year 2012, 2013 and 2014 were reviewed to identify animal studies. Each animal study was searched for 15 parameters specifically designed to review standards of animal experimentation and research methodology.

Observation:

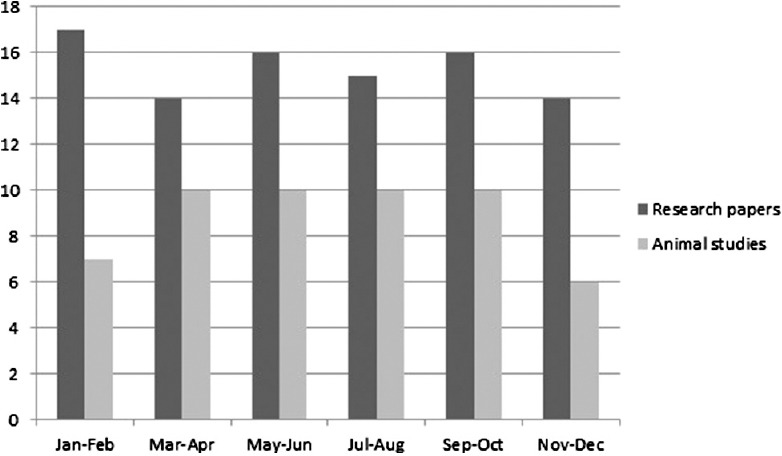

All published studies had clearly defined aims and objectives while a statement on ethical clearance about the study protocol was provided in 97% of papers. Information about animal strain and sex was given in 91.8% and 90% of papers respectively. Age of experimental animals was mentioned by 44.4% papers while source of animals was given in 50.8% papers. Randomization was reported by 37.4% while 9.9% studies reported blinding. Only 3.5% studies mentioned any limitations of their work.

Conclusion:

Present study demonstrates relatively good reporting standards in animal studies published in IJP. The items which need to be improved are randomization, blinding, sample size calculation, stating the limitations of study, sources of support and conflict of interest. The knowledge shared in the present paper could be used for better reporting of animal based experiments.

KEY WORDS: Animal experiments, blinding, randomization, reporting standards, research methodology

Introduction

Animal research is passing through a phase of intense debate all over the world.[1,2,3,4] Despite being a source of indispensable knowledge in the field of medical science, animal research has been criticized for reasons such as poor experimental design, low reproducibility, misinterpretation of results, inadequate statistical power, and inappropriate translation to humans, etc.[5] A large number of animals including rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, fishes, frogs, and primates are used for the purpose of research every year. Although exact figures are not known, it is estimated that 50–100 million animals are used for experimentation every year.[6]

Reporting of experimental details is as important as designing and conducting the experiment. There is an evidence from the literature that a major hurdle in reproducibility of preclinical studies is unsatisfactory or incomplete reporting of details about experimental animals and/or methods.[7] The details of experimental animals and methods, if provided may also prevent unnecessary repetition of work thereby saving resources including animals, money, and time, etc. Since animal research provides a foundation on which future clinical studies depend; poor designing or reporting of animal studies may even expose humans to unnecessary harm and danger.

Indian journal of pharmacology (IJP) is the official organ of Indian pharmacological society and is a leading, reputed journal in the field of pharmacology. The journal has a peer review process with an internationally recognized listing in indexing agencies such as PubMed, and science citation index expanded, etc.[8] Since animal research constitutes a major part of published material of IJP; it was considered worthwhile to conduct a survey on the reporting standards of published animal studies. The objective of the present survey study was to determine and knowing the reporting standards of animal studies published in IJP during the period of 2012–2014.

Materials and Methods

All the issues of IJP published in the year 2012, 2013, and 2014 were reviewed to identify animal studies. All research articles and short communications related to animal experiments were included. However, letters to the editor were not included in the present analysis because of brief information and word limitation. Similarly, studies involving purely in vitro experiments and those which used animals merely to procure tissue or organ for further study were also excluded.

Each animal study was searched for the following checklist: A clearly defined objective; a statement on ethical clearance; description of animal species, age, weight, sex, and source of animals; random allocation of animals to different groups, blinding, number of animals in each group (group size), sample size calculation, methods of statistical analysis, limitations of study, source of funding, facilities, and conflict of interests. Survey was done by two persons independently and any discrepancies were resolved by reanalysis of studies.

Observation

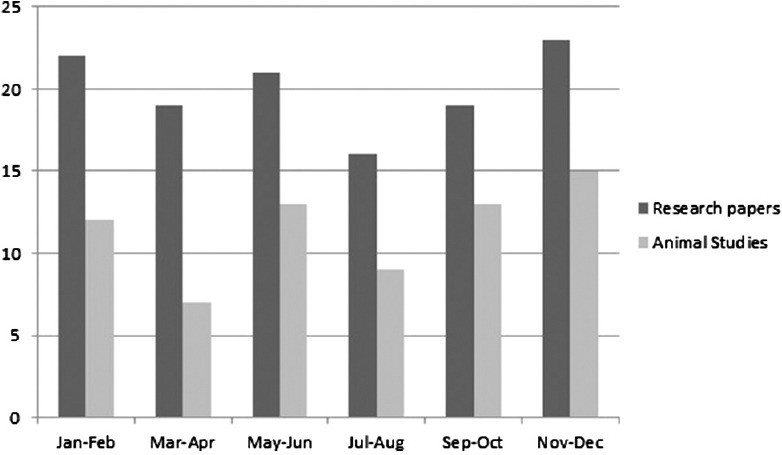

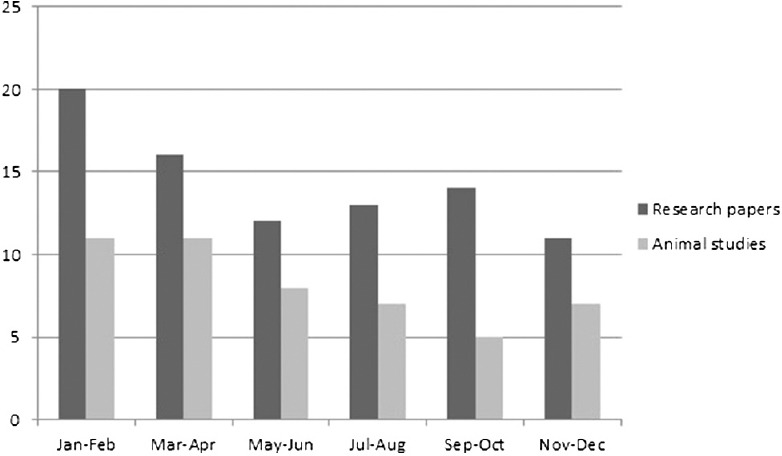

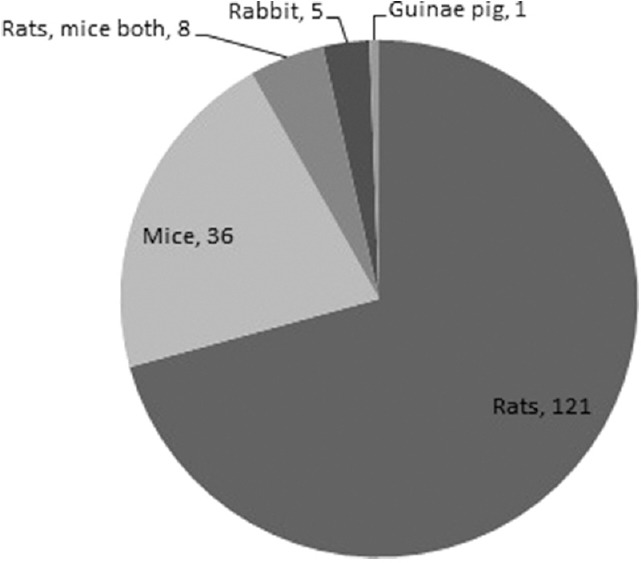

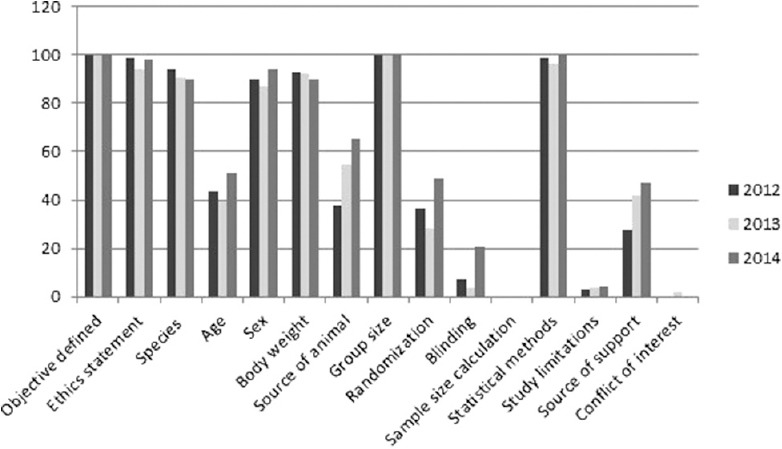

A total number of research papers, including research articles and short communications, published in between 2012 and 2014 were 298. During the same years, the total number of papers based on studies related to animal experimentation was found to be 171. In the year 2012, 69 (57.5%) research papers based on animal experimentation were published out of total 120 research papers. Similarly in the year 2013 and 2014, 92 and 86 full-length papers were published out of which 53 (57.6%) and 49 (56.9%), respectively, were based on animal experiment. Issue wise distribution of these research papers published in these 3 years is shown in Figures 1-3. Rats were used most commonly (70.7%) followed by mice (21.0%), and rabbits (2.9%). Both rats and mice were used in 4.6% studies [Figure 4]. Only one study used guinea pigs. The observed percentages of studies with various reporting criteria are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 1.

Issue wise distribution of research papers and animal studies in 2012

Figure 3.

Issue wise distribution of research papers and animal studies in 2014

Figure 4.

Distribution of studies by animal species used

Figure 5.

Percentages of studies with various reporting criteria

Figure 2.

Issue wise distribution of research papers and animal studies in 2013

All these published studies had a clearly defined objective. Similarly, a statement on ethical clearance about the study protocol was provided in 97% of papers. Information about animal strain was given in 91.8% papers. Sex of animals used was mentioned in 90% of studies. Age of experimental animals was mentioned by 44.4% papers while the source of animals was given in 50.8% papers.

We observed that 37.4% studies reported the random allocation of animals to experimental groups; however, none of these explained method used for randomization. Blinding of the observer in respect to which animal belonged to which treatment group, was reported by only 9.9% studies. None of the studies reported having undertaken any method to calculate sample size. A number of animals in each experimental group was given by all studies (either in material and methods section or in the results section, or as footnotes of Tables/Figures). Methods of statistical analysis were reported in 98.2% studies. Only 3.5% studies mentioned any limitations of their work. Source of support, either in the form of funding or facilities to carry out experiments was mentioned in 37.4% studies. Only one study reported not having any conflict of interest. Others had no statement on conflict of interest.

Discussion

Any research in pharmacology is incomplete without the animal experimentation. That is why, in our study, we found 57.3% papers solely on animal experimentation, a fairly good number representing more than half of all the papers. We also found that all published studies had a clearly defined objective. This could be the result of editorial prerequisite to define the objectives of the study before submission of the paper. Similarly, a statement on ethical clearance of study protocol was given by 97% of papers. Although it is clearly mentioned under “editorial policy” that “a statement on Ethics Committee permission and ethical practices must be included in all research articles under the ’materials and methods’ section,” still 3% of published studies did not report ethical clearance. Whether ethical clearance was taken, and only reporting was missed or clearance was not taken at all, is another important issue.

Providing details of animals used in the study is important to ensure the validity and reproducibility of results. In the present study, 91.8% of the papers mentioned animal strain, which is again a sign of good publication practices. Sex of animals used was mentioned in 90% of studies. This can be taken as a good percentage comparing with studies published in nature and the public library of science (PLoS) journals (79% and 68% respectively).[9] Age of experimental animals was mentioned by 44.4% papers. This could be a callous attitude of the researchers not to mention exact age. It is a common impression that it could suffices to mention phrases such as “mature animals,” “full-grown animals,” and “adult animals,” etc., instead of writing exact age.

The source of animals was mentioned in 50.8% of papers published over 3 years. However, it was observed that there was a gradual increase in reporting animal source from 2012 to 2014. It is important that the animals should be procured only from licensed suppliers. In India, animals can be obtained from the registered breeders or suppliers and kept in committee for the purpose of control and supervision of experiments on animals (CPCSEA) registered facility. Registered suppliers should provide information about the genetic and pathogenic status of animals. A period of quarantine may be required if information from the animal provider is insufficient, or if there was a risk of infection during transport.[10] The animal received from unauthorized local sources may become a source of infection for other animals as well as researchers.

Random allocation of animals to different experimental groups has been recommended to ensure baseline comparability and to equally distribute any confounding factors (known or unknown). Randomization also eliminates selection bias.[11] We observed that 37.4% studies reported the random allocation of animals to experimental groups; however, none of these explained the method used for randomization. This is again a satisfactory figure if we compare with a previous study where only 12% reported using randomization.[7] Moreover, the percentage of studies reporting random allocation increased in 2014 (48.9%) as compared to 2012 and 2013 (36.2% and 28.3% respectively).

Blinding of the observer, in respect to which the animal belonged to which treatment group, is another method to eliminate the bias in results.[11] However, in this survey, only 9.9% studies reported blinding. Similar to randomization, the percentage of studies reporting blinding improved in 2014 as compared to 2012, and 2013. None of the studies reported having undertaken any method to calculate sample size. As is the case with clinical studies, the inadequate sample size may lead to an inability to find a significant difference between treatment groups. As such, conducting such type of underpowered studies may be regarded as unethical.[12] One method to prevent this shortcoming at an early stage is to include a medical statistician into the existing Institutional Animal Ethics Committees. Low rates of reporting randomization, blinding, and sample size calculations have also been reported from high reputed journals in previous studies.[5,7] The number of animals in each experimental group was given by all studies observed in the present survey. Methods of statistical analysis were reported in 98.2% studies.

Only 3.5% studies mentioned any limitation of their research work. Limitations of study, if mentioned, might help to prevent wrong interpretation of results by other researchers as well as a guide in planning of future research work on the related topic.[13] Source of support, either in the form of funding or facilities to carry out experiments was mentioned in 37.4% of all studies. Similarly, only one study had a statement on conflict of interest. It should be noted that at the time of submission of a manuscript to IJP, authors have to declare any conflict of interest, but this information is not included in published manuscript. The statement on conflict of interest should always be published even when there are no conflicts. Nonfinancial (such as academic, political, or religious) conflicts should also be declared as they may be as potent as financial conflicts.[14]

In an effort to bring uniformity in reporting of animal studies, the Animal Research: Reporting of in vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines were developed by UK National Centre for the replacement, refinement and reduction of animals in research.[15] Introduced in 2010, ARRIVE guidelines have been endorsed by more than 300 journals (including BMC, PLoS, and nature group of journals, British Journal of Pharmacology, etc.,) and incorporated into their instructions to authors. Being similar to consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) statement;[16] which applies to clinical trials and has been shown to improve the quality of reporting, ARRIVE guidelines would also be a desirable inclusion into author guidelines of IJP.

Some of the limitations of this present survey study are that institutes or countries of work were not taken into account. Different practices in different institutes or countries can have an effect on survey results. Another limitation of this survey is that although we surveyed for reporting of statistical methods, we did not evaluate whether the statistical methods applied were appropriate or not. Use of inappropriate statistical tests is another issue which has been highlighted previously in animal research.[17] Despite these limitations, this survey provides useful information about the reporting standards of published animal experiments in IJP. It also highlights the areas where improvement is needed. Such kind of survey if conducted at regular intervals may over time improve the standards of reporting.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates relatively good reporting standards in animal studies published in IJP. The items which need to be improved are randomization, blinding, sample size calculation, stating the limitations of the study, sources of support and conflict of interest. The knowledge shared in the present paper could be used for better reporting of animal-based experiments. There is a need of enhancing awareness of ARRIVE guidelines among researchers as well as editors concerned with the animal experiments. Editors are in a unique position to improve manuscripts in this regard. Incomplete information should not be published. A checklist of essential information of any experiment based study should be provided to the author or to be uploaded at the journal website along with other publishing guidelines.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hartung T. Look back in anger – What clinical studies tell us about preclinical work. ALTEX. 2013;30:275–91. doi: 10.14573/altex.2013.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dikshit RK. Animal experiments: Confusion, contradiction, and controversy. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:661–2. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.103232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pound P, Ebrahim S, Sandercock P, Bracken MB, Roberts I. Reviewing Animal Trials Systematically (RATS) Group. Where is the evidence that animal research benefits humans? BMJ. 2004;328:514–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Worp HB, Howells DW, Sena ES, Porritt MJ, Rewell S, O’Collins V, et al. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker D, Lidster K, Sottomayor A, Amor S. Two years later: Journals are not yet enforcing the ARRIVE guidelines on reporting standards for pre-clinical animal studies. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badyal DK, Desai C. Animal use in pharmacology education and research: The changing scenario. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46:257–65. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.132153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilkenny C, Parsons N, Kadyszewski E, Festing MF, Cuthill IC, Fry D, et al. Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indian Journal of Pharmacology. [Last accessed on 2015 Aug 24]. Available from: http://www.ijp-online.com/aboutus.asp .

- 9.Pound P, Bracken MB. Is animal research sufficiently evidence based to be a cornerstone of biomedical research? BMJ. 2014;348:g3387. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), National Academy of Sciences; 2011. The National Academies Collection. Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Festing MF, Altman DG. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 2002;43:244–58. doi: 10.1093/ilar.43.4.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suresh K, Chandrashekara S. Sample size estimation and power analysis for clinical research studies. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:7–13. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.97779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Puhan MA, Akl EA, Bryant D, Xie F, Apolone G, ter Riet G. Discussing study limitations in reports of biomedical studies – The need for more transparency. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith R. Conflict of interest and the BMJ. BMJ. 1994;308:4–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6920.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang T. Twenty statistical errors even you can find in biomedical research articles. Croat Med J. 2004;45:361–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]