Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the prevalence, pattern, and awareness of self-medication practices among patients presenting at oral health outreach programs in coastal Karnataka, India.

Materials and Methods:

The cross-sectional study, based on an interview conducted in randomly selected 400 study subjects from the patients presenting at these oral health outreach programs. Data were collected regarding demographic information and the interview schedule consisting of 14 questions was administered.

Results:

Prevalence of self-medication was 30%. Respondents’ gender (χ2 = 5.095, P < 0.05), occupation (χ2 = 10.215, P < 0.05), the time from the last dental visit (χ2 = 8.108, P < 0.05), recommendation of drug(s) to family members or friends (χ2 = 75.565, P < 0.001), and the likelihood of self-medication in the next 6 months (χ2 = 80.999, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with self-medication. Male respondents were less likely to have undertaken self-medication (odds ratio = 0.581 [0.361, 0.933]). The frequently self-medicated drug was analgesics (42.5%) for toothache (69.2%). The regression model explained 39.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in self-medication practices.

Conclusions:

Prevalence of self-medication was 30% with demographic influence. Hence, this study highlights the policy implications for drug control by government agencies and stresses on the need for dental health education to discourage irrational drug use.

KEY WORDS: Dentists, drug resistance, oral health, self-medication

Introduction

Medications are one of the most important tools in public health practice. Since the 1980s, self-medication is of prime public health importance as World Health Organization, in order to reduce the burden on health care professionals changed some prescription drugs to be sold over-the-counter.[1] The pain as a symptom is primarily encountered in the dental profession and analgesics are routinely used along with antibiotics in order to avoid the need for dental consultation and treatment. Adverse drug reaction, drug interaction, expenditures, and global emergency of drug resistant pathogens are frequent results of inappropriate self-medication.[2,3] Self-medication is defined as “obtaining and consuming drugs without the advice of a doctor either for diagnosis, prescription, or surveillance of treatment.”[4] Self-medication is a universal phenomenon and practiced globally with a varied frequency of up to 68% in European countries,[5] while in the Indian sub-continent, prevalence rates of 31% in India[6] and 59% in Nepal have been reported.[7]

Drug retail shops are the part of the healthcare system which can be first point of contact for the patient population[8] In India, retail drug stores remain the most important medium of distribution with an extensive customer outreach. Pharmacists and pharmacy attendants play an important role in encouraging self-medication among the public.[9] Self-medication also encompasses the use of traditional medicine. The terms “traditional medicine,” “complementary medicine,” and “alternative medicine” that are used inter-changeably and include systems that are not integrated into the dominant health care system, but used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement, or treatment of illness.[10] Now a days, in India, it is common practice that patient may choose the varied range of practices, therapies, and treatments. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare set up the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy in November, 2003 with a view to providing focused attention to educational standards and standardization of drugs in this discipline.[11] The majority of the people turn to alternative medicine only after conventional medicine treatments have been exhausted.[12]

Mangalore in Karnataka state in India is spread over an area of 834 km2. The total population in 2011 was 989,856 among which the rural population was 209,578 (21.17%).[13] In rural areas, basic health care including dental treatment is not seen in isolation, but often part of a pluralistic medical system which coexists with alternative medicine and home remedies.[14] Responsible self-medication is a primary component of self-care. Data on current practices about self-medication for the dental condition is considered to be of vital importance for policy formulation. Information on self-medication practices for dental problems in India is lacking, and the scientific literature is sparse. Hence, the present study aimed to determine the trends in self-medication for dental problems amongst patients attending oral health outreach programs in coastal Karnataka, India.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The cross-sectional, interview based study was conducted at Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore under the aegis of Department of Public Health Dentistry, which conducts oral health outreach programs in various places in coastal Karnataka. The inclusion criteria included adult dental out patients aged 18 years or above presenting at dental outreach programs of the Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, while those who were unwilling to give informed consent and those not able to understand English/Kannada were excluded. Respondents were those patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and provided answers to the questionnaire. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Protocol No: 14025), and the study was conducted after obtaining written informed consent from participants.

Sample Size

A pilot study was conducted, prior to the start of the main study for sample size determination. The power and sample size was calculated by G*Power version 3.1.9.2 for Windows[15] (prevalence 0.4–0.7, α error probability = 0.05, power [1 − β] = 0.80). The final sample consisted of 400 study subjects, who were randomly selected from the patients presenting at these oral health outreach programs.

Translation of the Questionnaire

The interview schedule based on the questionnaire was translated into local language, Kannada in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines.[16] Two independent forward translations by bilingual translators was carried out after which the versions were compared. A third bilingual person helped to develop a single version of the survey. Another person blind to the original questionnaire then back translated the Kannada version questionnaire into English language, and it was compared to the original document to check the validity of the translation. An expert committee, comprised the translators, health and language professionals, met to produce the final questionnaire.

Data Collection

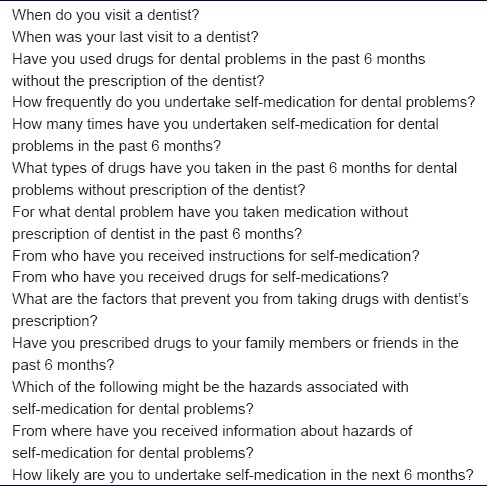

Patients are presenting at oral health outreach programs of Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore were administered the questionnaire by the principal investigator. Data were collected regarding demographic information such as age, gender, occupation, education, and monthly family income. The data were analyzed for prevalence, practices, and awareness of self-medication among dental patients presenting at the oral health outreach programs. The questionnaire was pretested for reliability and validity. The questionnaire consisted of 14 close ended questions. The first two questions of questionnaire assessed the dental practices of the respondents. The next three questions about self-medication among respondents elicited the prevalence while the following six questions dealt with the practices and the final three questions obtained their awareness. The data were coded and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, ver. 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was applied for testing significant associations between categorical variables and bivariate regression analysis was used to test if the patient characteristics significantly predicted self-medication practices. The level of statistical significance was kept at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

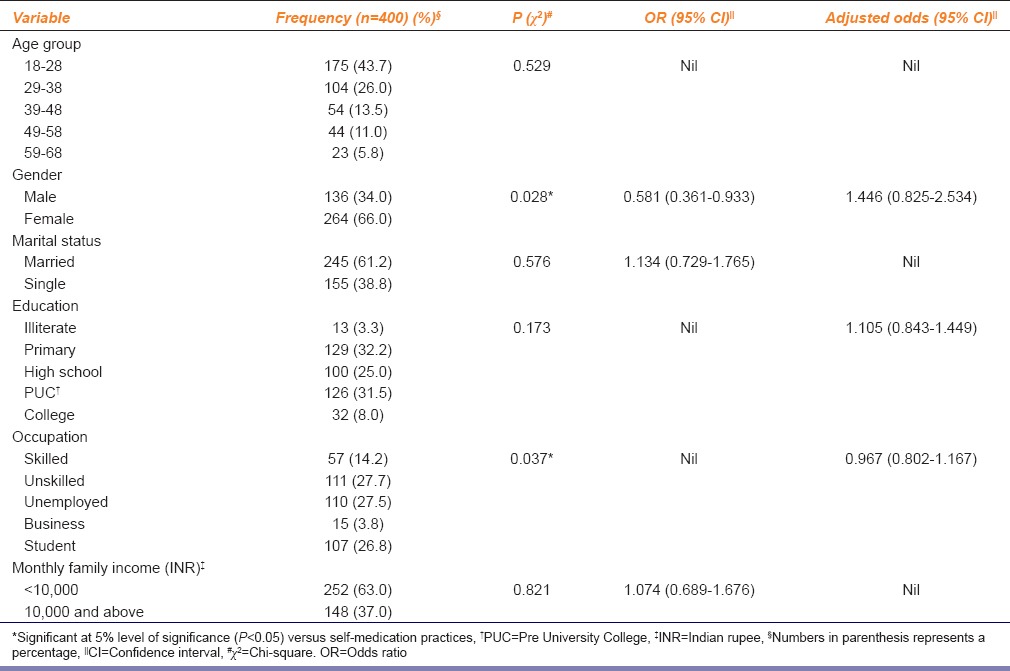

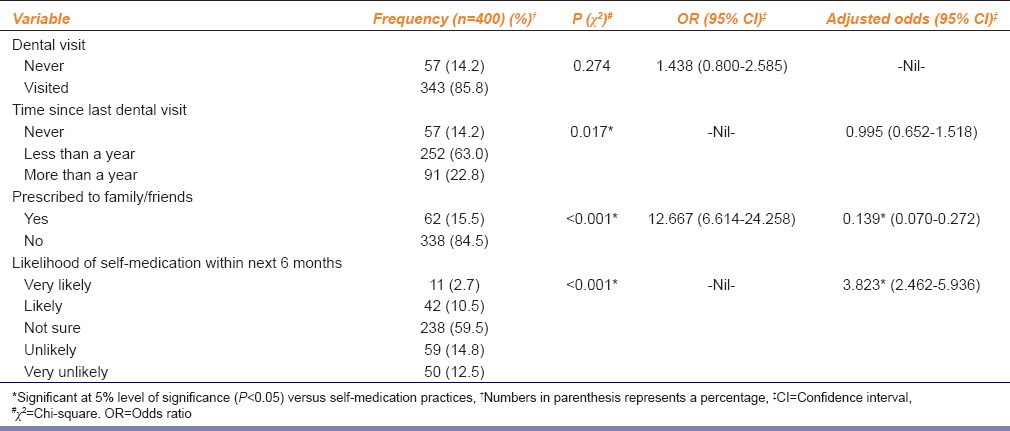

The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 66 years (33.51 ± 12.98). The majority of the respondents were married (61.2%) and the participation of females (66.0%) was more compared to males (34.0%). Only 3.3% of the respondents were illiterate while 27.5% of the respondents were unemployed, and 27.7% of them undertook unskilled work. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. Among the 400 respondents, 14.2% had never visited a dentist in their lifetime. Of those who had visited the dentist, 73.5% had a dental visit less than a year before [Table 2].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic factors associated with self-medication practices of study participants

Table 2.

Dental factors and study participant's practices associated with self-medication

Dental Self-medication

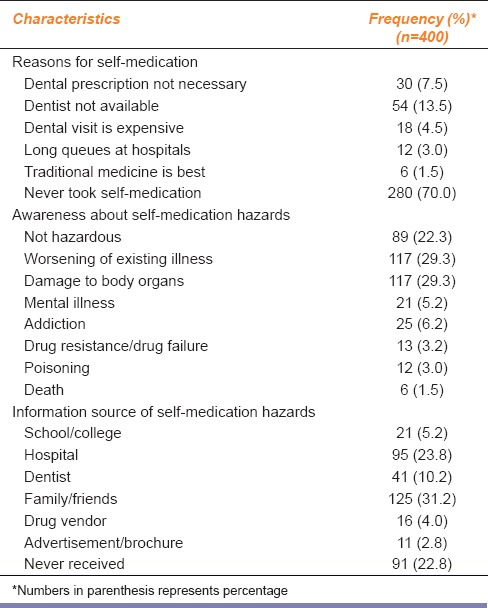

One hundred and twenty respondents (30%), among the total 400 respondents reported undertaking self-medication in the past 6 months. Among the 120 respondents who undertook self-medication, 49 respondents (40.8%) had self-medicated twice or more in the past 6 months, and 5 respondents (4.1%) always turned to self-medication for their dental problems. The frequently used drugs for self-medication were analgesics (42.5%), traditional medicines (14.2%), followed by antibiotics (10.0%). It was interesting to note that 33.3% of people undertaking self-medication were unaware of the drugs that they were consuming. The common dental problem warranting self-medication was a toothache (69.2%) followed by swelling in the face (17.5%) and gum problems (10.0%). The main source of drugs and instructions for self-medication was the drug vendor (62.5%), while others were influenced by family and friends (37.5%). In addition to undertaking self-medication themselves 15.5% of the respondents admitted as they are having prescribed a drug(s) for dental problems which were prescribed to their family members for their dental problems. About 13.2% of the respondents said that they were likely or very likely to undertake self-medication for dental problems in the next 6 months. The lack of access to dental services was the most common reason given for self-medication (13.5%). It was noted that 22.2% of the respondents felt that self-medication was not hazardous, while 22.8% had never received any information regarding hazards of self-medication Table 3.

Table 3.

Practice and awareness of self-medication for dental ailments among study participants

Associations with Dental Self-medication

On examination of the effect of sociodemographic variables like age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, and monthly family income, it was detected that respondents’ gender (χ2 = 5.095, P < 0.05) and occupation (χ2 = 10.215, P < 0.05) were significantly associated with self-medication. Male respondents were less likely to have undertaken self-medication (odds ratio [OR] = 0.581 [0.361, 0.933]) [Table 1]. When the effect of income (χ2 = 4.478, P = 0.038) and occupation (χ2 = 57.173, P < 0.001) on gender was further examined, it was noted that it was statistically significant. Self-medication was not significantly associated with dental visit, it was noted that tendency to self-medicate increased with time elapsed from the last dental visit which was statistically significant (χ2 = 8.108, P < 0.05) [Table 2]. It was noticed that respondents who themselves practiced self-medication were more likely to recommend drug(s) to their family members or friends (OR = 12.667 [6.614, 24.258]), which was statistically significant (χ2 = 75.565, P < 0.001) self-medication practices also showed statistical significance with the likelihood of self-medication in the next 6 months (χ2 = 80.999, P < 0.001) [Table 2].

A logistic regression was performed with variables that had a significance level of P ≤ 0.25.[17] We ascertained the effects of gender, education, occupation, time since last dental visit, prescription of drugs to family/friends, and likelihood of undertaking self-medication in the next 6 months on self-medication practices. The model explained 39.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in self-medication practices and correctly classified in to 70.0% of self-medication. Prescription of drugs to family/friends (β = −1.971, P < 0.001) and likelihood of undertaking self-medication in the next 6 months (β =1.341, P < 0.001) were associated with self-medication practices [Table 2]. The items contained in the interview schedule are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Items in the interview schedule

Discussion

The present study was an attempt to study the prevalence, pattern, and awareness of self-medication practices. To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine the self-medication practices among patients presenting at oral health outreach programs in India. Prescription drugs in India are easily available over-the-counter, in contrast to developed countries, e.g., European countries where strict criteria are in place to dispense drugs.[18] This could be a major reason for undertaking self-medication without a dentists’ prescription among 30% of our respondents. Lawan et al.[19] reported an association between age of the respondents and their practice of self-medication which was not observed in this study. Our study detected an association between gender and self-medication practices, where females were more likely to indulge in them. This finding is consistent with other studies which demonstrated a high prevalence of self-medication among females.[2,20,21,22,23] This may be due to lower threshold towards pain in females and greater fear of dental treatments among them.[2,23] It was also noted that majority of the females belonged to lower income groups and were more likely to be unemployed. In contrast, one study reported from Turkey found that males were 1.24 times more likely to use self-prescribed antibiotics than females.[24] Unlike a previous study,[19] conducted in Nigeria there was no association between marital status and self-medication practices.

While previous studies[2,7,19,25] have reported a positive association between level of education and self-medication, which was not observed in our study. The role of education in self-medication is unique, due to the fact that increased education makes people confident of self-medication while respondents who are illiterate may know the common drug names, color, and shape of the medication which assists them in self-medication.[9] Another factor associated with self-medication in our study was occupation, which was similar to findings reported from Nigeria by Lawan et al.[19] Occupation may be considered as a proxy for income levels, but monthly family income did not show any association with self-medication in our study. Other factors such as lack of time and work stress may influence the association of occupation on self-medication. There are also studies reported in the literature which supports the finding that prevalence of self-medication is higher among those in the lower economic status.[19,23]

There was no statistically significant association between self-medication and consulting a dentist, whereas, an increase in self-medication was positively associated with the time elapsed since the last dental visit. This could be attributed to the fact that during the recent dental visit, the respondent may have been instructed on taking medications by the dentist. This finding underlines the fact that regular dental visits may be beneficial to the patients in preventing self-medication. The finding that the frequently self-medicated drugs were analgesics followed by antibiotics is similar to observation of previous studies.[2,25] It is alarming that many of the respondents did not know what medications they were taking. A study among Indian dental students had reported that mouth ulcer was the most common reason for self-medication, that can be attributed to academic pressures.[25] But, in our study, toothache was the most common reason given for dental self-medication. Accordingly our study, found that hospitals and dentists were the major source (34.1%) of information regarding hazards of self-medication.

The drug vendor was the most common source of drugs, which demonstrates the need to control the sale of prescription drugs as over the counter medicines. In our study, the lack of access to dental services was the most common reason provided followed by the excuse that dentist prescription is not necessary. The reasons for self-medication according to earlier studies are long queues in the hospitals,[19] higher cost for dental treatment,[2] among others. There was an association between self-medication and prescription of drugs to family and friends. This suggests that in addition to people themselves undertaking self-medication, they also propagate this erroneous practice by recommending drugs to others. More than two-third of the respondents, 311 (77.7%) identified that self-medication may be hazardous, which was a similar finding reported earlier in literature.[19] The health hazards due to dental self-medication cannot be overlooked, since many people do not view their practices as self-medication. Self-medication was also associated with the likelihood of undertaking self-medication within the next 6 months, which shows the confidence with which the respondents’ self-medicated. The regression analysis showed an anomaly in the association between prescription of drugs to family/friends and self-medication, that the strong crude OR of 12.667 was reduced to 0.139 when adjusted for other variables. This finding needs to be cautiously interpreted.

The results of our study should be seen in the light of limitations. First, this study design was cross-sectional and, therefore, does not lead to causal inferences. The study population consisted of only patients reporting to outreach programs. Although this population is crucial to examine, these findings may have limited generalizability to other population. Free access to drugs along with ineffective drug regulations is a major cause of drug misuse. Nevertheless, if self-care practices are correctly implemented, they can contribute immensely to the sensible use of medicines. In India, where there is no dental insurance, affordability may also be an important factor in oral health practices. Dental health education should be implemented on a priority to make people aware of the dangers of self-medication.

Conclusions

This study concluded that the prevalence of self-medication in this population was 30%. Male gender and the recent dental visit was found to be less likely associated with self-medication. This study also establishes that the family members or friends of patients undertaking self-medication are also at a risk. In India, access to dental facilities is poor. One reason for the lower prevalence in this study may be that the respondents were attenders at dental clinics. Self-medication might be higher among nonattenders. Future studies can be done on community dwellers so as to get a more accurate picture of self-medication among the population of coastal Karnataka. Clearer policy, stricter regulations, and constant monitoring are needed from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Government of India.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help provided by Dr. Kavitha Ashok, Dr. Vijayendranath Nayak S and Dr. Nuzha Mariam, lecturers in the Department of Public Health Dentistry, Manipal College of Dental Sciences, Mangalore, Manipal University.

References

- 1.Albany NY. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1988. Guidelines for Developing National Drug Policies. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baig QA, Muzaffar D, Afaq A, Bilal S, Iqbal N. Prevalence of self-medication among dental patients. Pak Oral Dent J. 2012;32:292–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.López JJ, Dennis R, Moscoso SM. A study of self-medication in a neighborhood in Bogotá. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota) 2009;11:432–42. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642009000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montastruc JL, Bagheri H, Geraud T, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Pharmacovigilance of self-medication. Therapie. 1997;52:105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretagne JF, Richard-Molard B, Honnorat C, Caekaert A, Barthélemy P. Gastroesophageal reflux in the French general population: National survey of 8000 adults. Presse Med. 2006;35(1 Pt 1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(06)74515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshpande SG, Tiwari R. Self medication – A growing concern. Indian J Med Sci. 1997;51:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar PR, Partha P, Shenoy N. Self-medication and non-doctor prescription practices in Pokhara valley, Western Nepal: A questionnaire-based study. BMC Fam Pract. 2002;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kafle KK, Madden JM, Shrestha AD, Karkee SB, Das PL, Pradhan YM, et al. Can licensed drug sellers contribute to safe motherhood?. A survey of the treatment of pregnancy-related anaemia in Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1577–88. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamat VR, Nichter M. Pharmacies, self-medication and pharmaceutical marketing in Bombay, India. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:779–94. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2000. [Last cited on 2014 Jun 22]. General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine. Available from: http://www.ncarboretum.org/assets/File/PDFs/Research/WHO_EDM_TRM_20001.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of AYUSH. Government of India. 2014. [Last cited on 2014 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.indianmedicine.nic.in/

- 12.Tabish SA. Complementary and alternative healthcare: Is it evidence-based? Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2008;2:V–IX. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dakshina Kannada District at a Glance. Mangalore: Government of Karnataka. 2011. [Last cited on 2014 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.dk.nic.in/other/ankiamsha1112.pdf .

- 14.Vandebroek I, Calewaert JB, De jonckheere S, Sanca S, Semo L, Van Damme P, et al. Use of medicinal plants and pharmaceuticals by indigenous communities in the Bolivian Andes and Amazon. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:243–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. [Last cited on 2014 Jun 22]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 17.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Koliofoti ID, Koutroumpa IC, Giannakakis IA, Ioannidis JP. Pathways for inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics for rhinosinusitis: A randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:76–82. doi: 10.1086/320888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawan UM, Abubakar IS, Jibo AM, Rufai A. Pattern, awareness and perceptions of health hazards associated with self medication among adult residents of kano metropolis, northwestern Nigeria. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:144–51. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.116350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worku S, Mariam AG. Practice of self-medication in Jimmatown, Nigeria. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2003;17:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angeles-Chimal P, Medina-Flores ML, Molina-Rodríguez JF. Self-medication in a urban population of Cuernavaca, Morelos. Salud Publica Mex. 1992;34:554–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Awad A, Eltayeb I, Matowe L, Thalib L. Self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials in the community of Khartoum State, Sudan. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8:326–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adedapo HA, Lawal AO, Adisa AO, Adeyemi BF. Non-doctor consultations and self-medication practices in patients seen at a tertiary dental center in Ibadan. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:795–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.94671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilhan MN, Durukan E, Ilhan SO, Aksakal FN, Ozkan S, Bumin MA. Self-medication with antibiotics: Questionnaire survey among primary care center attendants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:1150–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalyan VS, Sudhakar K, Srinivas P, Sudhakar G, Pratap K, Padma T M. Evaluation of self-medication practices among undergraduate dental students of a tertiary care teaching dental hospital in South India. J Educ Ethics Dent. 2013;3:21–5. [Google Scholar]