Modal activity at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, in which open channel probability switches reversibly between discrete values, arises from changes in the resting affinity at the agonist site.

Abstract

The time course of the endplate current is determined by the rate and equilibrium constants for acetylcholine receptor (AChR) activation. We measured these constants in single-channel currents from AChRs with mutations at the neurotransmitter-binding sites, in loop C. The main findings are: (a) Almost all perturbations of loop C generate heterogeneity in the channel open probability (“modes”). (b) Modes are generated by different affinities for ACh that can be either higher or lower than in the wild-type receptors. (c) The modes are stable, in so far as each receptor maintains its affinity for at least several minutes. (d) Different agonists show different degrees of modal activity. With the loop C mutation αP197A, there are four modes with ACh but only two with partial agonists. (e) The affinity variations arise exclusively from the αδ-binding site. (f) Substituting four γ-subunit residues into the δ subunit (three in loop E and one in the β5–β5′ linker) reduces modal activity. (g) At each neurotransmitter-binding site, affinity is determined by a core of five aromatic residues. Modes are eliminated by an alanine mutation at δW57 but not at the other aromatics. (h) Modes are eliminated by a phenylalanine substitution at all core aromatics except αY93. The results suggest that, at the αδ agonist site, loop C and the complementary subunit surface can each adopt alternative conformations and interact with each other to influence the position of δW57 with respect to the aromatic core and, hence, affinity.

INTRODUCTION

The endplate acetylcholine receptor (AChR) is a hetero-pentamer of subunit composition α2βδε (adult) or α2βδγ (fetal). Each receptor has two agonist-binding sites located in the extracellular domain at αδ- and either αε- or αγ-subunit interfaces, and each site has a core of five aromatic residues (Fig. 1). In mouse AChRs, at the two adult sites (αε and αδ), αY190, αY198, and αW149 are the main sources of ACh affinity and together generate a resting equilibrium Kd of ∼150 µM (Jadey et al., 2011; Purohit et al., 2012; Nayak et al., 2014). At the fetal αγ site, αY93 and especially γW55 also contribute to increase the resting affinity for ACh to ∼5 µM.

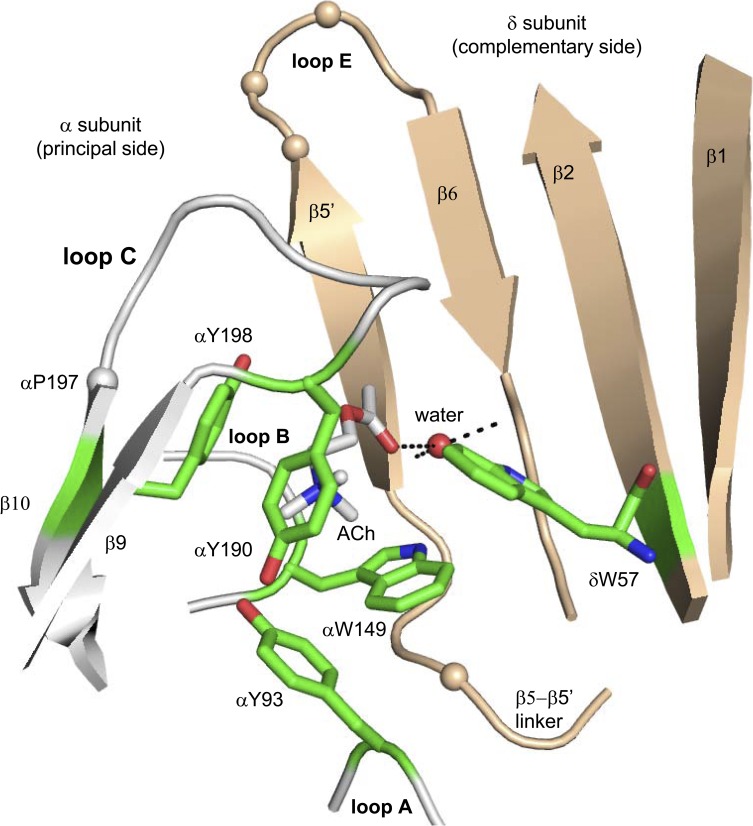

Figure 1.

The ligand-binding site of an acetylcholine binding protein. The agonist-binding sites are at subunit interfaces; the principal side (α subunit in AChRs) is white, and the complementary side (δ, ε, or γ subunit) is tan. The structure is Lymnaea stagnalis (Protein Data Bank accession no. 3WIP; Olsen et al., 2014), and residue numbers are mouse endplate AChRs. Green, aromatic core; tan spheres, αC atoms of γ-subunit substitutions (see Fig. 6); red sphere, structural water; dashed lines, H bonds.

The principal (α-subunit) side of each agonist site is formed by loops A, B, and C. Loop C covers the binding pocket and contains αY190 and αY198 residues that make approximately the same contribution to affinity at all three kinds of agonist site (αε, αγ, and αδ). The removal of loop C does not affect constitutive gating but eliminates the agonist response (Purohit and Auerbach, 2013). The complementary (non–α-subunit) side of each agonist site is a super-secondary structure that is mostly β sheet. The higher resting affinity of the fetal αγ site is set by residues in loop E and the β5–β5′ linker, which influence the contribution of γW55 (W57 in the δ subunit; unpublished data).

The consistency of a synaptic response depends, in part, on the consistency of the underlying binding and gating rate and equilibrium constants that shape the current. Hence, different open probability (PO) modes of activation will generate different synaptic responses. Single-channel modes have been reported for several different WT synaptic receptors, including for ACh (Auerbach and Lingle, 1986; Naranjo and Brehm, 1993), GABA (Lema and Auerbach, 2006), glycine (Hurdiss et al., 2015), AMPA (Poon et al., 2010; Prieto and Wollmuth, 2010), and NMDA (Popescu and Auerbach, 2003; Magleby, 2004; Zhang et al., 2008). Mode shifts have also been observed in other WT ion channels (Blatz and Magleby, 1986; Nilius, 1987; McManus and Magleby, 1988; Smith and Ashford, 1998; Ionescu et al., 2007; Chakrapani et al., 2011). It is of general interest to understand the molecular basis of modal activity, even if this may arise by different mechanisms in different ion channels.

We have explored the effects of mouse endplate AChR loop C mutations with regard to the consistency of binding and gating constants, estimated from single-channel currents. Almost all α-loop C perturbations unsettle resting affinity and generate distinct, stable PO modes. The affinity variations arise exclusively at the αδ agonist site, with patterns that are different for different agonists. We explore a possible mechanism in which α-loop C and the δ-subunit β sheet each take on alternative conformations to set the structure of the aromatic core and affinity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and mutagenesis

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum plus 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin, pH 7.4, and were incubated at 37°C (5% CO2). The QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to incorporate mutations into the mouse AChR cDNAs, which were verified by nucleotide sequencing. Transient transfection of cDNAs into HEK293 cells was either by a calcium phosphate precipitation method or by using TransIT-293 transfection reagent (Mirus). After transfection, cells were incubated for ∼16–24 h at 37°C before electrophysiological recordings commenced.

Electrophysiology

Single-channel currents were recorded at 23°C in the cell-attached patch configuration. The bath solution was Dulbecco’s PBS containing 137 mM NaCl, 0.9 mM CaCl2, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.4. The pipette solution was PBS. In some experiments, an agonist (acetylcholine, carbamylcholine, tetramethylammonium [TMA], or choline) was added only to the pipette solution. For experiments without ligands, we used a pipette holder and electrode that were never exposed to any agonists. When low [agonist] were used, the pipette potential was 70 mV, which corresponds to a membrane potential of approximately −100 mV (inward currents). When high [agonist] were used, the pipette potential was −100 mV, which corresponds to a membrane potential of approximately 70 mV (outward currents) to reduce channel block by the agonist. When necessary, rate constants were corrected for the effect of voltage (Nayak et al., 2012). Single-channel currents were low-pass filtered at 20 kHz and digitized at a sampling frequency of 50 kHz. Collection and analyses of the currents were performed using QuB software (Nicolai and Sachs, 2013).

Cluster selection and Kd/PO estimation

Single-channel currents associated with C↔O gating occur as clusters separated by long desensitized periods (Sakmann et al., 1980). Sometimes, a tcrit value of 6.5 ms was used define a cluster (for example, Fig. 2 A). However, there often was a wide distribution of intra-cluster shut-interval durations making it impossible to use a single tcrit value (Fig. 2 B). In these patches, clusters were selected by eye. In either case, a k-means clustering algorithm was applied to the selected clusters to determine the number of PO populations and to segregate the clusters for mode-by-mode analysis.

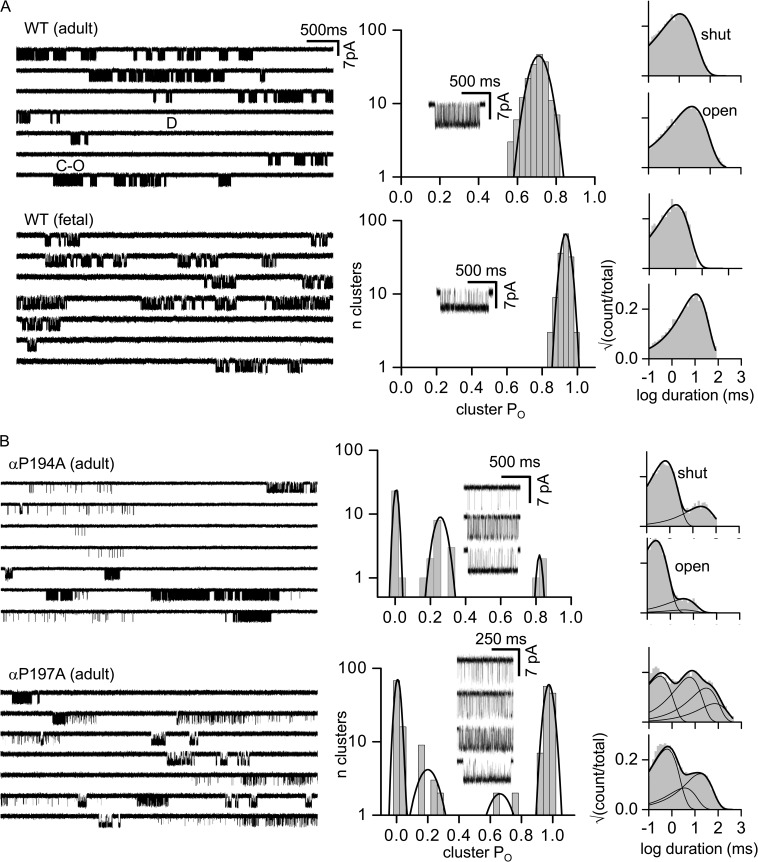

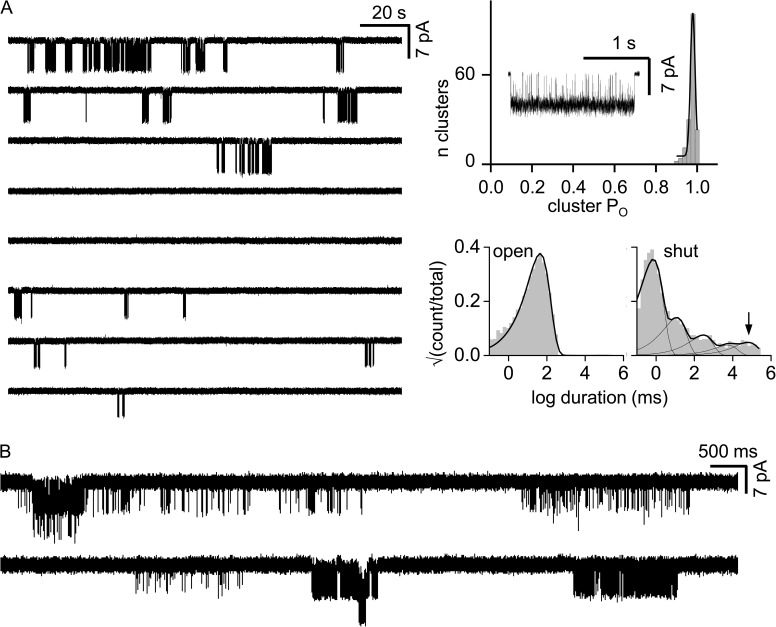

Figure 2.

Loop C proline mutations generate PO modes. WT AChR clusters are homogenous. (A; left) Single-channel currents (30 µM ACh; −100 mV; open is down). Clusters of openings are binding-gating events (C-O) and long silent intervals between clusters are desensitization (D). (Right) Histograms of cluster PO (fitted by a single Gaussian) and intra-cluster interval durations (fitted by a single exponential). (Inset) An example cluster. In both adult and fetal AChRs, there is only a single PO population (0.70 ± 0.06, 187, and 0.93 ± 0.03, 156; mean ± SD; n clusters). (B) Loop C mutations αP197A and αP194A in adult AChRs induce modes. PO histograms for αP197A have four populations (0.01 ± 0.01, 83; 0.20 ± 0.04, 6; 0.67 ± 0.06, 8; and 0.96 ± 0.01, 110), and multiple exponentials are required to describe the interval duration distributions.

For rate constant estimation, intra-cluster currents for each PO population were idealized into noise-free intervals by using the segmental k-means algorithm, after low-pass filtering at 12 kHz. The forward (f) and backward (b) gating rate constants were estimated from the interval durations by fitting with a C↔O model and a maximum-interval likelihood algorithm after imposing a dead time of 20–50 µs. Occasionally, an additional shut state was added to account for a short-lived desensitized state (Elenes and Auerbach, 2002). The gating equilibrium constant was calculated from the ratio of the rate constants, En = fn/bn, where n is the number of bound agonists. PO was calculated from the gating equilibrium constant, PO = (1 + En−1)−1. For unliganded gating, E0 was calculated from the ratio of closed-/open-time constant, using the main component of each interval duration histogram.

AChR gating is described by a cyclic mechanism (Auerbach, 2012). In brief, WT receptors are active constitutively but with a small unliganded gating equilibrium constant (allosteric constant) that generates a very low PO (Jackson, 1986; Purohit and Auerbach, 2009; Nayak et al., 2012). PO is increased by agonists because these ligands bind with a higher affinity to the O versus C conformation. Accordingly, the gating equilibrium constant with one bound agonist (E1) is the product of the gating equilibrium constant without any agonists (E0) and the C/O equilibrium dissociation constant ratio. Cluster PO with agonists is a function of both resting affinity (Kd) and the allosteric constant (E0).

A shortcut was used to estimate Kd. This was possible because in mouse endplate AChRs, affinity and efficacy are correlated (Jadey and Auerbach, 2012; Purohit et al., 2014). With n equal-affinity neurotransmitter-binding sites, the resting affinity Kd can be calculated from the unliganded and fully liganded gating equilibrium constants by using:

| (1) |

For example, in adult WT AChRs (−100 mV), n = 2, E0 = 7.4 × 10−7, and E2ACh = 25, so from Eq. 1, we calculate KdACh = 172 µM, which is about the same as that measured by standard dose–response methods (Jadey et al., 2011).

Backgrounds

In many experiments, the goal was simply to count the number of cluster PO populations. To facilitate this enumeration, a background mutation(s) was often added simply to increase E0 and place the shut and open intervals into an optimal range for cluster formation and PO analysis (Jadey et al., 2011). In these cases, it was not necessary to know the quantitative effect of the background on E0. For example, for WT adult AChRs, E0 is small (the shut intervals between openings are long) and clusters cannot be defined. To increase the unliganded channel-opening frequency, we added two background mutations, βL262G and δL265G, both far away from the binding site at the M2 gate region. This pair of mutations increased the unliganded opening rate constant by ∼26,000-fold, to reveal clusters having PO of ≈0.02 (Fig. 3 A, top).

Figure 3.

Gating of loop C proline mutants in the absence of agonists is homogeneous. (A; left) Single-channel clusters from unliganded AChRs (adult type, −100 mV; background mutation were added to increase constitutive activity; see Materials and methods). (Right) Intra-cluster interval duration histograms and an example cluster. WT, αP194A, and αP197A show both brief and long (arrow) unliganded openings. The briefer, main component of each distribution represents C-O gating; the longer open component(s) is characteristic of unliganded activity but is distinct from C-O and of unknown origin (Purohit and Auerbach, 2009). (B) Adding the agonist site mutation αY93F eliminates long unliganded openings but does not affect the gating open interval time constant (Purohit and Auerbach, 2010).

The background mutations used to increase E0 (by x-fold) and facilitate cluster counting as are follows: Fig. 4 B, εS450W (9.95-fold); Fig. 5, εS450A (17-fold); Fig. 6, either δ(P123R + W57A) to knock-out the αδ site (0.06-fold), or εP121R to knock-out the αε site (0.09-fold; Gupta et al., 2013) plus βV266A (446-fold; Fig. 6, A and C), βV266A + εS450W (4438-fold; Fig. 6 B, top), or γL260Q (3,570-fold; Fig. 6 B, bottom); Fig. 7, αC192A and αC193A (εS450A), αY190A (αD97A + αY127F + εS450W; 98,600-fold), αY198A, αC192 deletion, and αT196P (εL269F; 176.8-fold); Fig. 8 A, the αε knockout mutations plus εL269F; Fig. 8 B, for αW149A and αY198A (εL269F) and for αY93A (εS450A); Fig. 9 A, for αY190F and αW149F (εL269F); Fig. 9, the αε knockout plus for αY190F (δL265G + δI43Q + εL269F; 1.105-fold), for αY198F (δI43Q + εL269F; 81-fold), and for δW57F (εL269F). In all other experiments, the background was adult WT. Again, all of the backgrounds only served to increase E0 to enhance cluster formation (Jadey et al., 2011).

Figure 4.

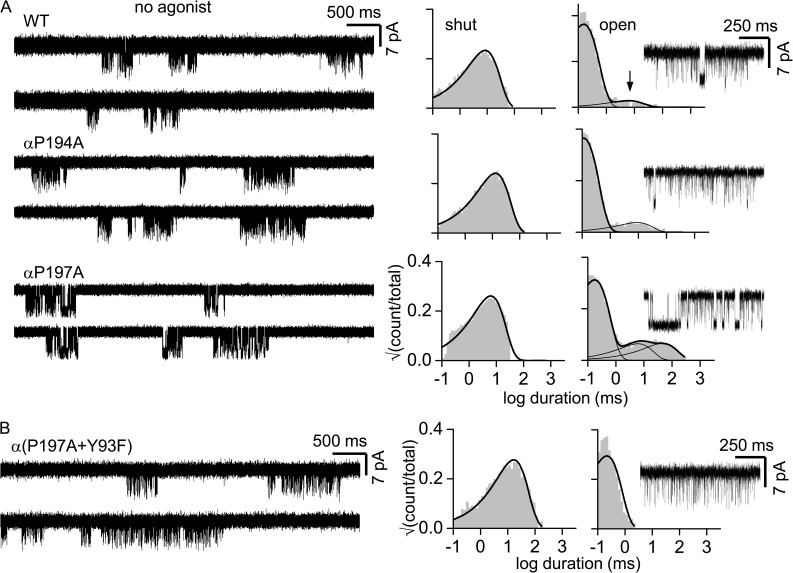

Partial agonists generate fewer modes than does ACh. (A; left) Example clusters for αP197A adult AChRs ([agonist] = 1 mM; −100 mV; open is down). (Right) Cluster PO histogram for TMA with peaks at 0.04 ± 0.01 and 0.87 ± 0.10. Arrow, PO for TMA in WT AChRs (0.30 ± 0.06). The full agonist ACh has four PO populations (Fig. 2 B, bottom). (B) αP197A adult AChRs activated by a saturating [Cho] (100 mM; 70 mV; open is up). (Top) Two modes are apparent. (Bottom left) Interval duration histograms and example clusters of each mode. (C) Phi (slope) analysis of αP197A choline modes. The fold-change in the di-liganded gating equilibrium constant is caused mainly by a similar fold-change in the channel-opening rate constant.

Figure 5.

Modes are stable. (A; left) Low time-resolution view of αP197A (+αY93A) clusters from a patch having a single AChR. (Right) Corresponding histograms (adult AChR, 30 µM ACh; −100 mV; open is down). For ∼30 min, PO was homogeneous. (Right, bottom) The slowest shut component (arrow; 162 ± 70 s), which represents recovery from deep desensitization, is similar to the WT value (270 s; Elenes and Auerbach, 2002), indicating that the patch probably had only one AChR. (B) A multichannel patch of the same construct shows PO modes.

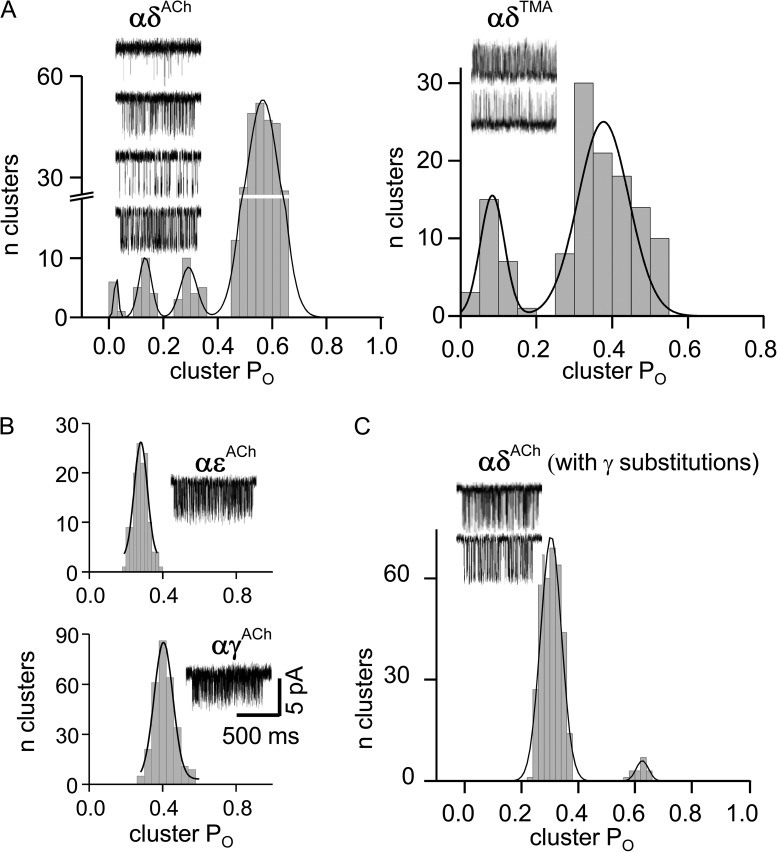

Figure 6.

Modes are generated only at the αδ agonist site. (A) With only a functional αδ site there, are four POACh and two POTMA populations, as in the WT. (B) Modes are absent in AChRs with only a functional αε or αγ site. (C) Substituting side chains from the γ subunit into the δ subunit (three in loop E and one in the β5–β5′ linker; see Fig. 1) reduces modal activity. Open is down for ACh (−100 mV; 100 µM for αδ and αε, and 30 µM for αγ) and up for TMA (70 mV; 5 mM).

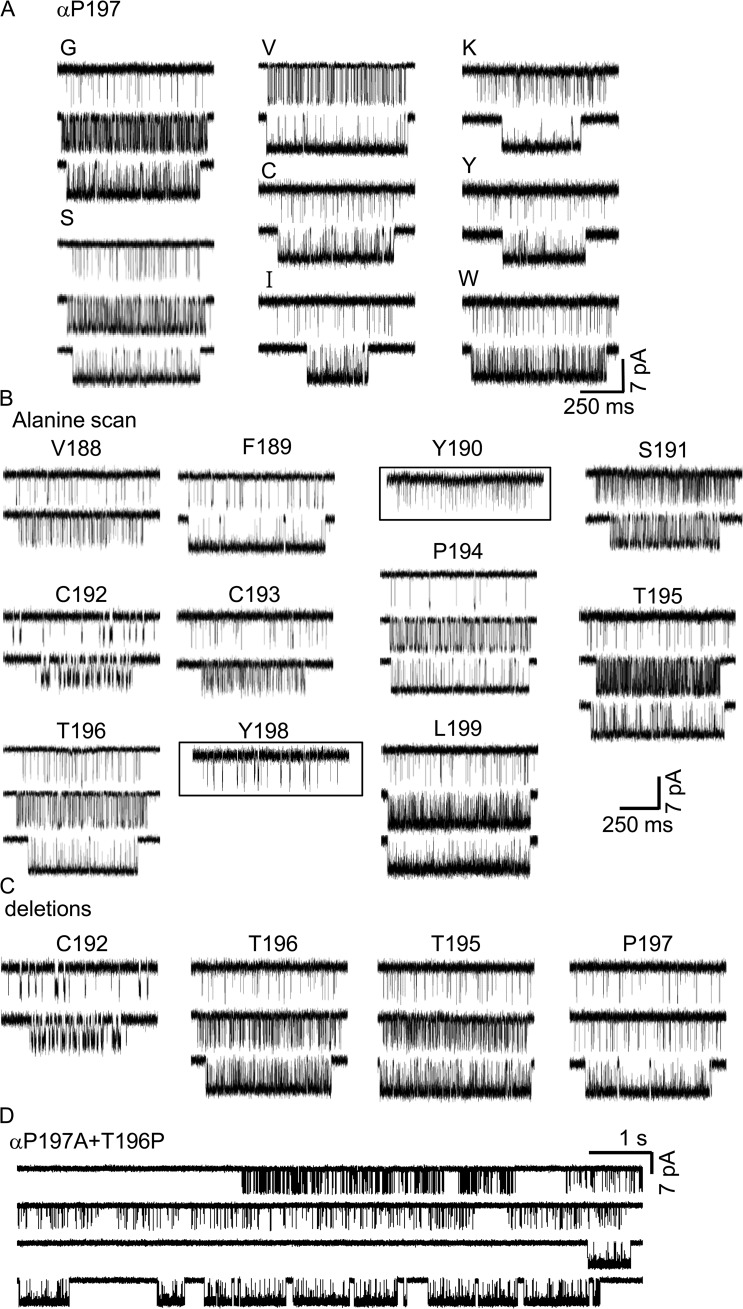

Figure 7.

Example currents for α-subunit loop C perturbations. (A) Modes with different substitutions at αP197. For each mutation, examples of the various modes are shown directly below the mutant designation. Only two modes are apparent with larger side chains (see Fig. 2 for Ala mutation). (B) Alanine scan of loop C. Modes are apparent with an alanine substitution at every loop C position except αY190 and αY198 (boxed). (C) Deletions. Modes are present with deletions of some loop C residues. (D) Modes are present with αT196P added to the αP197A background. All experiments: adult AChRs, 30 µM ACh; −100 mV; open is down.

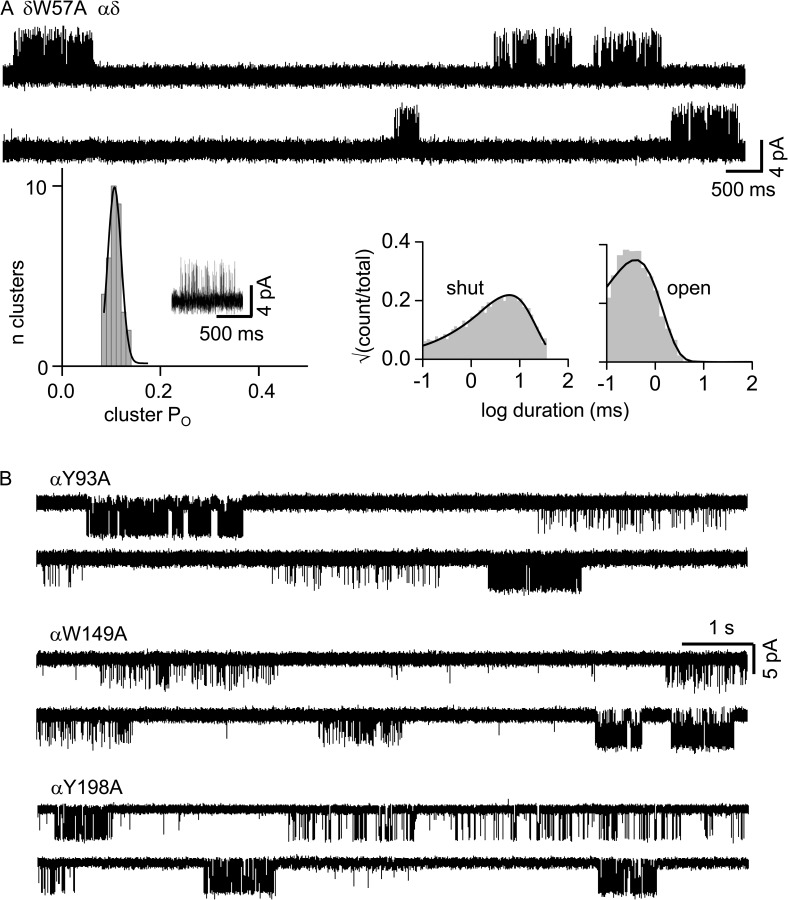

Figure 8.

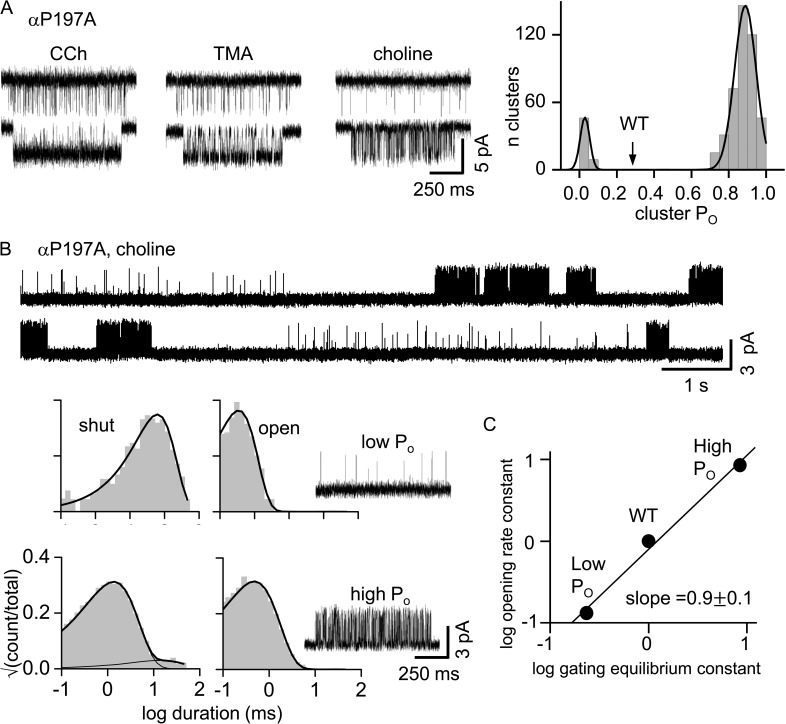

Alanine scan of the aromatic core. (A) δW57A. (Top) Example currents from a single-site, αδ-only AChR (3 mM ACh; 70 mV; open is up). (Bottom) Cluster PO and interval duration histograms. Only one PO population is apparent (KdACh given in Table 1). (B) Example currents from other alanine mutants. Multiple modes are apparent (two-site, adult AChRs; 30 µM ACh; −100 mV; open is down). αP197A was present for all.

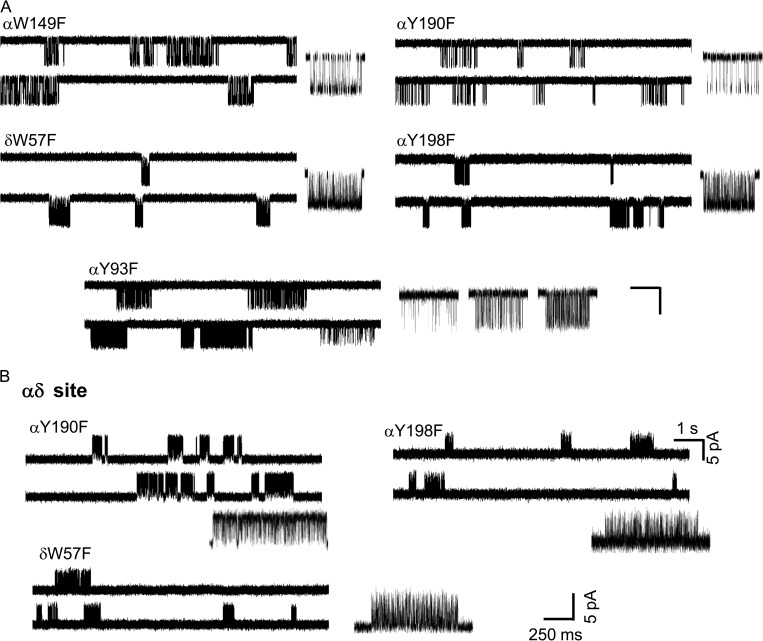

Figure 9.

Phenylalanine scan of the aromatic core. (A) All F substitutions eliminate αP197A modes except for αY93F (two-site, adult AChRs; 30 µM ACh; −100 mV; open is down). Calibration, 1 s/7 pA (low resolution traces) and 250 ms, 5 pA (high resolution clusters). (B) F substitutions at one-site, αδ-only AChRs (3 mM ACh; 70 mV; open is up). Clusters from αY190F, αY198F, and δW57F are homogeneous.

To estimate Kd for different modes (Table 1), it was necessary to know both E1 and E0 (Eq. 1). We added a background mutation(s) that increased E0 over the adult WT value, each by a known factor. When multiple mutations were added, we assumed that the effects were independent, so that the product of the individual fold-changes estimated the combined effect. E2 was estimated from the measured values of fn and bn, as described above.

Table 1.

Affinity of modes at the αδ site

| Agonist | Mode | E1obs | E1corr | Kd | ΔG |

| µM | kcal/mol | ||||

| TMA | H | 0.7 | 2.6 × 10−3 | 25.8 | −6.2 |

| L | 0.004 | 1.5 × 10−5 | 4,470 | −3.2 | |

| ACh | HHH | 3.7 | 0.09 | 0.74 | −8.3 |

| HH | 0.9 | 0.02 | 3.4 | −7.4 | |

| H | 0.2 | 5 × 10−3 | 13.4 | −6.6 | |

| L | 0.01 | 2.5 × 10−4 | 268 | −4.8 | |

| ACha | − | 0.1 | 6.3 × 10−3 | 10.6 | −6.7 |

All AChRs had αP197A and the αε knockout mutation εP121R (70 mV; [TMA] = 5 mM and [ACh] = 10 mM). Mode, H for high PO and L for low PO. E1obs, observed gating equilibrium constant with one agonist at the αδ site; E1corr, gating equilibrium constant after correction for the background mutations; Kd = (E0WT/E1corr), where E0WT = 6.7 × 10−8 at 70 mV (Nayak et al., 2012); ΔG, αδ-binding free energy (+0.59 lnKd). The adult WT, αδ Kd values are: TMA (580 µM; −4.4 kcal/mol) and ACh (175 µM; −5.1 kcal/mol). Additional background mutations (total fold increase in E0): TMA, εL269F + εS450A (271); ACh, βV266A (40), ACha, εL269F (16).

δW57A added to the background (WT value is KdACh = 80 µM; −5.6 kcal/mol (Nayak et al., 2014).

RESULTS

Modes

Fig. 2 A shows ACh-activated single-channel currents from WT AChRs. Openings occur in clusters that contain many cycles of binding and gating, and that are separated by long, silent sojourns in desensitized states. In both adult and fetal AChRs, the distribution of intra-cluster PO was approximately Gaussian and consistent, patch-to-patch. In some recordings, there were also isolated, brief openings interspersed between the clusters. Aside from these, the single-channel current properties of adult and fetal WT AChRs are essentially homogeneous.

In mouse endplate AChRs, α-subunit loop C (β9–β10 linker) has the sequence VFYSCCPTTPYL (α188–α199). We first examined the effects of alanine substitutions at either of the two prolines (Fig. 2 B). Unlike in the WT, clusters from adult AChRs having the mutation αP194A or αP197A showed a multimodal distribution of POACh values. In αP197A, there are four different cluster populations (modes) having PO values between 0.01 and 0.96, in addition to isolated openings.

Heterogeneity in PO can be caused by differences in gating (the allosteric constant, which is the unliganded gating equilibrium constant; see Materials and methods), the resting affinity (Kd), or both. We therefore examined αP194A and αP197A clusters without adding any agonists (Fig. 3). To do so, we added background mutations far from the agonist sites that increased the level of constitutive activity but had no effect on Kd. The loop C mutations αP194A or αP197A had no or little effect on the allosteric constant. Moreover, neither of these loop C proline mutations resulted in unliganded PO heterogeneity. This result indicates that the different POACh values apparent with agonist and the loop C proline mutations are generated by variations in KdACh.

In the next set of experiments, we changed the agonist, using the αP197A mutation. With 1 mM of the partial agonists carbamylcholine, TMA, or choline, only two PO populations were apparent, both different than the WT (Fig. 4 A).

We also measured the opening and closing rate constants for each of the αP197A modes using a saturating [agonist] (Fig. 4 B). The difference in the di-liganded gating equilibrium constant between modes arose almost exclusively from a change in the opening rate constant (Fig. 4 C). This is characteristic of many α-subunit residues at the agonist sites (Purohit et al., 2013), and suggests that the structural perturbation responsible for the affinity variation is occurring locally, probably at loop C.

Regardless of the agonist, PO was uniform within each cluster. We did not observe mode switching within ∼1,000 αP197A clusters, which suggests that the time constant for mode switching is on the order of at least several minutes. By chance, we happened to record currents from a patch that had only a single AChR (Fig. 5 A). Although this construct showed heterogeneity in POACh in multichannel patches (Fig. 5 B), in the one-channel patch, the clusters were homogeneous. In this experiment, the time scale for mode switching was more than ∼30 min. In a one-channel patch, the long, closed intervals between clusters reflect desensitized periods of just that AChR (Elenes and Auerbach, 2002). The consistency of cluster PO in this patch suggests that the affinity changes caused by αP197A are not associated with recovery from desensitization.

In all of the experiments described above, both AChR agonist sites were active and contributed to the cluster PO. We next examined the properties of each agonist site separately (αγ, αδ, or αε). We added a binding site knockout mutation, in addition to a background mutation(s) that increased the allosteric constant, to allow the production of clusters and the measurement of PO. Fig. 6 shows that with the αP197A mutation (in both α subunits) and ACh, the αε- and αγ-generated currents were homogeneous, but those arising from αδ were modal. As in adult, two-site AChRs, the αδ-only receptors produced four POACh populations and two POTMA populations. This result suggests that all of the heterogeneity is caused by affinity variations at the αδ site.

To estimate the differences in affinity between modes at the αδ site, we used a saturating concentration of agonist (Eq. 1 and Table 1). For TMA, the αP197A mutation resulted in AChRs having either an ∼22-fold higher affinity or an ∼8-fold lower affinity than the WT αδ site. For ACh, three modes were higher affinity (by 2,326-, 51-, and 13-fold) and one was lower affinity (1.5-fold) than the WT. With both of these agonists, none of the αP197A-induced Kd values was the same as in the WT.

The results presented so far indicate that in endplate AChRs, α-loop C proline-to-alanine mutations (a) generate stable variations in resting affinity, (b) that are different from the WT, (c) for several different agonists, (d) only at the αδ site, (e) by virtue of a local perturbation, and (f) by a mechanism that is independent of desensitization.

Mutations

To test whether or not modes are something specific to the proline-to-alanine loop C substitutions, we substituted different side chains at αP197. With ACh and in two-site adult AChRs, four modes were apparent with A, three with G and S, but only two with V, C, I, K, Y, and W (Fig. 7 A). This pattern suggests that larger side chain substitutions produce less heterogeneity.

We also substituted an alanine at each of the other loop C positions (Fig. 7 B). POACh heterogeneity was present in all cases, with two exceptions. Mutation of either of the two loop C tyrosines that are part of the aromatic core (αY190A and αY198A) generated clusters that were homogeneous. Variation in affinity is not specific to mutations of the prolines.

We examined the properties of adult-type muscle AChRs having a deletion of one loop C amino acid (both α subunits). The deletion of αC192, αT195, αT196, or αP197 all resulted in modal PO values (Fig. 7 C). We also replaced αT196 with a proline, on the αP197A background. This construct, too, produced multiple POACh values (Fig. 7 D).

In the next series of experiments, we examined the effects of mutating a core aromatic residue on αP197A-induced modes. Without this loop C mutation, an alanine substitution at αY198 or αW149 decreases affinity to a similar extent (∼30-fold; ∼2.0 kcal/mol) at all three agonist sites (αε, αδ, and αγ). In contrast, the effect of the complementary-side mutation W55A (it is position 57 in δ) is variable and reduces affinity by ∼2,000-fold (4.3 kcal/mol) at αγ and ∼15-fold (1.5 kcal/mol) at αε, but at αδ it increases affinity by twofold (−0.5 kcal/mol; Nayak et al., 2014).

To explore the role of this “variable” amino acid with regard to modes, we added δW57A to αP197A and used ACh to activate AChRs having only a functional αδ site (Fig. 8). The cluster PO values were homogeneous, and KdACh was lower than with a WT loop C (Table 1). Apparently, the δW57 mutation eliminates the alternative loop C conformations responsible for modes. αP197A modes were still apparent with an alanine substitution at αY198 (loop C), αW149 (loop B), or αY93 (loop A).

We also counted modes from the αP197A mutation in AChRs activated by ACh and having only a functional αδ site, but this time with an additional F mutation at one of the core aromatics (Fig. 9). An F mutation conserves the aromatic character of the side chain but removes H bonds made by the side chains. αP197A modal activity was eliminated or greatly reduced by αY190F, αY198F, αW149F, and δW57F, but remained unaltered by αY93F.

In the final set of experiments, we analyzed the effects of mutations to δ subunit amino acids on the complementary β sheet (Fig. 1). Recently, it was discovered that low-affinity αδ and high-affinity αγ binding energies can be exchanged by swapping four complementary side chains, three in loop E (δY113, δD114, and δS115) and one in the β5–β5′ linker, near αW149 (δY106; unpublished data). Because αγ alone does not exhibit modes, we investigated the effects of exchanging these four side chains on αδ modal activity. We replaced these four side chains in δ with the corresponding ones from γ, and observed that the αP197A-induced modes with ACh were greatly reduced (Fig. 6 C).

The mutational analyses suggest that (a) almost all perturbations of loop C unsettle αδ affinity, (b) δW57 is a source of the affinity variations, (c) H-bonding patterns at the aromatic core influence the variations, and (d) loop E and the β5–β5′ linker in the δ subunit contribute to modal activity.

DISCUSSION

In muscle nicotinic AChRs, almost all α-subunit loop C perturbations cause modal gating activity, with the PO differences generated by variations in Kd at the αδ agonist site. To explore a potential mechanism, we begin with some assumptions and inferences based on experimental observations.

In AChRs, Kd is determined by diffusion of the agonist to a binding site and a local, conformation change at the agonist site (Jadey and Auerbach, 2012). We assume that modes reflect differences in the equilibrium constant of this conformational change (“catch”) rather than diffusion. Kd is determined mainly by the interaction of aromatic side chains at the core with the ligand’s quaternary amino group (Kearney et al., 1996; Zhong et al., 1998; Beene et al., 2002). We assume that different affinities reflect relatively different positions of the quaternary amino within the aromatic core (Bruhova et al., 2013). A difference in binding energy can be associated with a difference in conformation (structure, dynamics, or both), but the converse is not necessarily true because different conformations can generate identical affinities. Nonetheless, we assume a one-to-one correspondence between conformation and Kd, because of the high sensitivity of the measurements and because the PO distributions are approximately Gaussian. Based on these three assumptions, we conclude that in WT AChRs, there is (approximately) one catch conformation, and that perturbing loop C of the α subunit allows for more than one.

αP197A modes are stable on a time scale of minutes (Fig. 5), which implies that the free energy barriers separating alternative catch conformations are large. We infer that each mode represents a different, stable Kd conformation. These conformations may reflect different protein folds or different posttranslational modifications. Modes are generated by almost all α-loop C perturbations (Fig. 7). This result implies that the conformational uniformity of the WT binding pocket is readily disrupted by altering loop C. We cannot be sure that the WT α-loop C sequence is the only “golden” one, but it appears that residues here have been selected to enforce a single affinity, perhaps to increase the reliability of the endplate current. Loop C is involved in agonist binding and has high-phi for gating (like modes; Fig. 4 C), and so far it is the main structural element associated with mode generation. We infer that differences in α-subunit loop C structure/dynamics motivate the alternative Kd conformations. Modes arise exclusively from the αδ site and are reduced by swapping loop E side chains, δ-to-γ (Fig. 6). We infer that alternative conformations of the complementary subunit (for short, the ‘β-sheet’) are also involved in mode generation.

There are four modes apparent with αP197A and ACh (Figs. 2 B and 6 A). A simple interpretation, based on the above assumptions and inferences, is that two structural elements—the α-loop C and the δ-subunit β sheet—each can adopt two alternative Kd conformations. With the αP197A mutation, none of the Kd values are the same as in the WT (Table 1). We hypothesize that none of the four possible catch conformations are the same as in the WT. We call this a 2 × 2 mechanism.

Undoubtedly, the situation is more complex. First, loop C of the α subunit and the β sheet of the non–α subunit do not operate independently. Interactions between the α and δ subunits can occur through side chains, the agonist itself, a structural water in the pocket (Amiri et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2014), intersubunit H bonds, as well as through backbone breathing motions (Taly et al., 2005). Second, each of the two structural elements in the 2 × 2 model is complex. Loop C interacts with other loops in the α-subunit site of the binding pocket, and the non–α-subunit surface is a super-secondary structure having several components (β sheet, β5′–β6 hairpin turn, β5–β5′ linker, and a structural water; Fig. 1). Given this complexity, it is difficult to dissect unambiguously the possible route(s) for mode generation. Nonetheless, we will use the simple 2 × 2 model as the starting point for interpreting the experimental results.

(a) αP197A induces four modes with ACh but only two for the partial agonists TMA, carbamylcholine, and choline. The partial agonists probably do not H bond across the subunit interface or with the structural water. We speculate that these ligands do not have this α–δ link, and therefore that αP197A allows the two loop C conformations, but not those of the β sheet. The agonist and structural water appear to participate in Kd variation.

(b) With ACh, only two modes are apparent with V, C, I, K, Y, and W mutations of αP197 (Fig. 7). We speculate that having a large side chain here favors one of the alternative loop C conformations that nonetheless allows for two conformations of the β sheet. Steric bumping with other loops at the binding pocket (Grutter et al., 2003) appears to play a role in Kd variation.

(c) An alanine mutation of all loop C residues generates modes except for the two loop C tyrosines that “clamp” the agonist in the pocket. This result suggests that all three elements of this clamp are required for loop C to adopt alternative conformations. We speculate that with only one tyrosine, α-loop C adopts a single, preferred conformation that does not allow β-sheet alternatives. The two loop C tyrosines are involved in mode generation.

(d) αP197 modes are eliminated by an A substitution at core residue δW57 but not at αW149, αY198, or αY93. This complicates the model because it makes β-sheet residue δW57 an instigator of, rather than a responder to, α-loop C alternatives. If δW57 is simply one element of the β-sheet alternatives, the 2 × 2 model predicts two modes (the loop C alternatives), whereas only one was apparent. Hence, δW57 either interacts with loop C to alter its conformational flexibility (which is surprising, because this side chain has almost no effect on affinity in the WT), or can take on alternative positions that result in the same affinity for different loop C configurations (violating assumption c, above). δW57 appears to be an important and variable source for the modal differences in agonist-binding energy.

(e) αP197A modes are reduced by δ-subunit mutations in loop E and the β5–β5′ linker. The loop E mutations change H-bond patterns and backbone dynamics of the β sheet to influence the participation of δW57 (unpublished data). The flexibility of the β5′–β6 hairpin may also influence Kd modes.

(f) αP197A modes are greatly reduced by an F substitution at αY190, αY198, αW149, and δW57 but not αY93. This suggests that the complete network of H bonds formed by the two loop C tyrosine–OH groups and the two indole nitrogen atoms is required for mode generation by αP197A. We cannot speculate further, except to propose that variation in H bonding, too, is involved in Kd variability.

It has been 30 years since PO modes were first reported for AChRs. Here, we have shown that these arise from stable differences in affinity, at the αδ agonist site, as influenced by loop C and the complementary β sheet. The ligand, a structural water, δW57, loop E, and H bonds at the core of the αδ site all appear to participate. The agonist-binding apparatus is intricate and entangled. More and different kinds of experiments may be required to fully reveal the molecular mechanism(s) that undergirds the modal affinities of endplate AChRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marlene Shero, Mary Merritt, and Mary Teeling for technical assistance.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant NS064969).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Kenton J. Swartz served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- AChR

- acetylcholine receptor

- PO

- open probability

- TMA

- tetramethylammonium

References

- Amiri S., Sansom M.S., and Biggin P.C.. 2007. Molecular dynamics studies of AChBP with nicotine and carbamylcholine: the role of water in the binding pocket. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 20:353–359. 10.1093/protein/gzm029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A. 2012. Thinking in cycles: MWC is a good model for acetylcholine receptor-channels. J. Physiol. 590:93–98. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A., and Lingle C.J.. 1986. Heterogeneous kinetic properties of acetylcholine receptor channels in Xenopus myocytes. J. Physiol. 378:119–140. 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beene D.L., Brandt G.S., Zhong W., Zacharias N.M., Lester H.A., and Dougherty D.A.. 2002. Cation-pi interactions in ligand recognition by serotonergic (5-HT3A) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: the anomalous binding properties of nicotine. Biochemistry. 41:10262–10269. 10.1021/bi020266d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatz A.L., and Magleby K.L.. 1986. Quantitative description of three modes of activity of fast chloride channels from rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 378:141–174. 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhova I., Gregg T., and Auerbach A.. 2013. Energy for wild-type acetylcholine receptor channel gating from different choline derivatives. Biophys. J. 104:565–574. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.11.3833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S., Cordero-Morales J.F., Jogini V., Pan A.C., Cortes D.M., Roux B., and Perozo E.. 2011. On the structural basis of modal gating behavior in K(+) channels. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:67–74. 10.1038/nsmb.1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenes S., and Auerbach A.. 2002. Desensitization of diliganded mouse muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels. J. Physiol. 541:367–383. 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.016022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutter T., Prado de Carvalho L., Le Novère N., Corringer P.J., Edelstein S., and Changeux J.P.. 2003. An H-bond between two residues from different loops of the acetylcholine binding site contributes to the activation mechanism of nicotinic receptors. EMBO J. 22:1990–2003. 10.1093/emboj/cdg197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Purohit P., and Auerbach A.. 2013. Function of interfacial prolines at the transmitter-binding sites of the neuromuscular acetylcholine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 288:12667–12679. 10.1074/jbc.M112.443911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurdiss E.J., Greiner T., Yu R., Biggin P.C., and Sivilotti L.G.. 2015. The kinetic properties of the human glycine receptor in response to different agonists. Biophys. J. 108:432a 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.2360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu L., White C., Cheung K.H., Shuai J., Parker I., Pearson J.E., Foskett J.K., and Mak D.O.D.. 2007. Mode switching is the major mechanism of ligand regulation of InsP3 receptor calcium release channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 130:631–645. 10.1085/jgp.200709859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.B. 1986. Kinetics of unliganded acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Biophys. J. 49:663–672. 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83693-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadey S., and Auerbach A.. 2012. An integrated catch-and-hold mechanism activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:17–28. 10.1085/jgp.201210801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadey S.V., Purohit P., Bruhova I., Gregg T.M., and Auerbach A.. 2011. Design and control of acetylcholine receptor conformational change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:4328–4333. 10.1073/pnas.1016617108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney P.C., Nowak M.W., Zhong W., Silverman S.K., Lester H.A., and Dougherty D.A.. 1996. Dose-response relations for unnatural amino acids at the agonist binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: tests with novel side chains and with several agonists. Mol. Pharmacol. 50:1401–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lema G.M., and Auerbach A.. 2006. Modes and models of GABA(A) receptor gating. J. Physiol. 572:183–200. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.099093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K.L. 2004. Modal gating of NMDA receptors. Trends Neurosci. 27:231–233. 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus O.B., and Magleby K.L.. 1988. Kinetic states and modes of single large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 402:79–120. 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo D., and Brehm P.. 1993. Modal shifts in acetylcholine receptor channel gating confer subunit-dependent desensitization. Science. 260:1811–1814. 10.1126/science.8511590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak T.K., Purohit P.G., and Auerbach A.. 2012. The intrinsic energy of the gating isomerization of a neuromuscular acetylcholine receptor channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 139:349–358. 10.1085/jgp.201110752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak T.K., Bruhova I., Chakraborty S., Gupta S., Zheng W., and Auerbach A.. 2014. Functional differences between neurotransmitter binding sites of muscle acetylcholine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:17660–17665. 10.1073/pnas.1414378111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai C., and Sachs F.. 2013. Solving ion channel kinetics with the QuB software. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 08:191–211. 10.1142/S1793048013300053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B. 1987. Modal gating behaviour of single sodium channels from the guinea-pig heart. Biomed. Biochim. Acta. 46:S662–S667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J.A., Balle T., Gajhede M., Ahring P.K., and Kastrup J.S.. 2014. Molecular recognition of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine by an acetylcholine binding protein reveals determinants of binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. PLoS One. 9:e91232 10.1371/journal.pone.0091232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon K., Nowak L.M., and Oswald R.E.. 2010. Characterizing single-channel behavior of GluA3 receptors. Biophys. J. 99:1437–1446. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu G., and Auerbach A.. 2003. Modal gating of NMDA receptors and the shape of their synaptic response. Nat. Neurosci. 6:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto M.L., and Wollmuth L.P.. 2010. Gating modes in AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 30:4449–4459. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5613-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., and Auerbach A.. 2009. Unliganded gating of acetylcholine receptor channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:115–120. 10.1073/pnas.0809272106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., and Auerbach A.. 2010. Energetics of gating at the apo-acetylcholine receptor transmitter binding site. J. Gen. Physiol. 135:321–331. 10.1085/jgp.200910384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., and Auerbach A.. 2013. Loop C and the mechanism of acetylcholine receptor-channel gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 141:467–478. 10.1085/jgp.201210946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., Bruhova I., and Auerbach A.. 2012. Sources of energy for gating by neurotransmitters in acetylcholine receptor channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:9384–9389. 10.1073/pnas.1203633109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., Gupta S., Jadey S., and Auerbach A.. 2013. Functional anatomy of an allosteric protein. Nat. Commun. 4:2984 10.1038/ncomms3984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit P., Bruhova I., Gupta S., and Auerbach A.. 2014. Catch-and-hold activation of muscle acetylcholine receptors having transmitter binding site mutations. Biophys. J. 107:88–99. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B., Patlak J., and Neher E.. 1980. Single acetylcholine-activated channels show burst-kinetics in presence of desensitizing concentrations of agonist. Nature. 286:71–73. 10.1038/286071a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.A., and Ashford M.L.. 1998. Mode switching characterizes the activity of large conductance potassium channels recorded from rat cortical fused nerve terminals. J. Physiol. 513:733–747. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.733ba.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taly A., Delarue M., Grutter T., Nilges M., Le Novère N., Corringer P.-J., and Changeux J.-P.. 2005. Normal mode analysis suggests a quaternary twist model for the nicotinic receptor gating mechanism. Biophys. J. 88:3954–3965. 10.1529/biophysj.104.050229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Howe J.R., and Popescu G.K.. 2008. Distinct gating modes determine the biphasic relaxation of NMDA receptor currents. Nat. Neurosci. 11:1373–1375. 10.1038/nn.2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W., Gallivan J.P., Zhang Y., Li L., Lester H.A., and Dougherty D.A.. 1998. From ab initio quantum mechanics to molecular neurobiology: a cation-pi binding site in the nicotinic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:12088–12093. 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]