Abstract

Immediate early genes (IEGs) of the early growth response gene (Egr) family are activated in the brain in response to stress, social stimuli, and administration of psycho-active medications. However, little is known about the role of these genes in the biological or behavioral response to these stimuli. Here we show that mice lacking the IEG transcription factor Egr3 (Egr3–/– mice) display increased aggression, and a decreased latency to attack, in response to the stressful social stimulus of a foreign intruder. Together with our findings of persistent and intrusive olfactory-mediated social investigation of conspecifics, these results suggest increased impulsivity in Egr3–/– mice. We also show that the aggression of Egr3–/– mice is significantly inhibited with chronic administration of the antipsychotic medication clozapine. Despite their sensitivity to this therapeutic effect of clozapine, Egr3–/– mice display a marked resistance to the sedating effects of acute clozapine compared with WT littermate controls. This indicates that the therapeutic, anti-aggressive action of clozapine is separable from its sedating activity, and that the biological abnormality resulting from loss of Egr3 distinguishes these different mechanisms. Thus Egr3–/– mice may provide an important tool for elucidating the mechanism of action of clozapine, as well as for understanding the biology underlying aggressive behavior. Notably, schizophrenia patients display a similar decreased susceptibility to the side effects of antipsychotic medications compared to non-psychiatric controls, despite the medications producing a therapeutic response. This suggests the possibility that Egr3–/– mice may provide insight into the neurobiological abnormalities underlying schizophrenia.

Keywords: immediate early gene, Egr3, clozapine, behavior, stress, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Immediate early genes (IEGs) are rapidly activated in the brain in response to changes in the environment including social stimuli (Numan et al, 1998; Hoke et al, 2005), stress (Senba and Ueyama, 1997; Meaney et al, 2000), psychoactive medications (Nguyen et al, 1992; Yamagata et al, 1994), and electroconvulsive stimulation (O'Donovan et al, 1998). These genes have thus been used experimentally as markers of regional brain activity in response to a wide range of stimuli. In addition, these genes play important roles in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (Yamagata et al, 1994; Jones et al, 2001; Bozon et al, 2002, 2003; Li et al, 2005). However, much less is known about the involvement of these genes in the regulation of behavior, or in the organism's response to pharmacologic agents, or other stimuli that activate their expression in the brain.

We have studied mice deficient for the IEG transcription factor Early Growth Response Gene (Egr) 3 (Tourtellotte and Milbrandt, 1998). Egr3 is activated in the brain in a pattern similar to that of the more well-known family member Egr1 (also called NGFI-A, zif-268, or Krox 24) (Yamagata et al, 1994). Though less well studied than Egr1, expression of Egr3 is induced by many of the same stimuli as Egr1, including stress and psychoactive agents including antipsychotic medications (Yamagata et al, 1994; Honkaniemi et al, 2000). We recently found that Egr3–/– mice display a heightened reactivity to stress and abnormalities in their adaptation to novel and stressful stimuli (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007). In addition we found that Egr3–/– mice have deficits in long-term depression (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007), a form of synaptic plasticity triggered by stressful and novel stimuli (Kim et al, 1996; Xu et al, 1997; Manahan-Vaughan and Braunewell, 1999; Braunewell and Manahan-Vaughan, 2001; Artola et al, 2006).

We have also noted that Egr3–/– mice display abnormalities in social interactions with their cagemates (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007). We therefore decided to investigate the response of Egr3–/– mice to a stressful social stimulus to further characterize the role of this IEG in behavior. In addition, since Egr3 is activated in response to antipsychotics (Yamagata et al, 1994), we were particularly interested in ascertaining whether this activation is essential for the response to one such medication by testing whether the behavioral abnormalities of Egr3–/– mice were reversible by treatment with clozapine, a drug known for its high level of efficacy, particularly in patients with refractory symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Previously-generated Egr3–/– mice (Tourtellotte and Milbrandt, 1998) were back-crossed to C57BL/6 mice for 13 generations. Animals were housed on a 12 h light/dark schedule with ad libitum access to food and water. Studies were conducted on adult male littermate progeny of heterozygote matings. Investigators were blind to the genotype and treatment conditions of animals in all studies.

Behavioral Testing

Behavioral testing was performed during daytime hours under ambient light conditions. Cohorts of animals were tested in multiple behavioral studies with several intervening test-free days. Tests involving administration of drug were performed at the end of the test battery.

Resident-Intruder Test of Aggression

Male ‘resident’ mice were individually housed for a minimum of 10 days before testing, and cage bedding was not changed for atleast 4 days before testing, to facilitate territorial behavior. The test was performed as described in Crawley (2000). In brief, a novel, group-housed adult C57BL/6 male ‘intruder’ was introduced into the resident's cage for a 10 min test session on two separate occasions, spaced 3–7 days apart. Following each trial intruder mice were inspected for injuries and wiped with 70% ethanol to remove olfactory cues before replacement in their home cages to reduce home cage aggression. Intruders were used only once per testing day, and were eliminated from further use if they displayed offensive aggressive behaviors. Sessions were videotaped and subsequently scored for total duration and latency to onset of a range of social behaviors using Stopwatch + software (Brown, 2002). Behaviors scored as aggression included biting events as well as ‘fighting’, which was defined as aggressive attacks in which individual biting events could not be distinguished (eg due to reciprocal behavior from the intruder).

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

Mice were deeply anesthetized with halothane and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sectioned in 500 μm slices in ice-cold PBS using a vibratome. Brain regions were rapidly dissected on ice, weighed, transferred to 1.5 ml tubes, and homogenized in PCA buffer (0.1 N perchloric acid, 0.4 nM Na2S2O5), and stored on ice protected from light. Samples were then sonicated for 15 s, centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min, and supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and stored at −80°C. Samples were analyzed with electrochemical detection for concentration of the following neurotransmitters and their metabolites: serotonin (5-HT), 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA), dopamine (DA), 3,4 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), and homovanillic acid (HVA), as described previously (Pehek et al, 1992). Independent samples t-tests were performed for statistical analyses.

Activity Monitoring

Activity was evaluated in transparent (47.6×25.4.×20.6 cm high) polystyrene enclosures using a computerized photobeam system (MotorMonitor, Hamilton Kinder, Poway, CA) as described previously (Schaefer et al, 2000). Activity was calculated using number of movements (total photobeam breaks) as the dependent variable for total activity. Locomotor activity monitoring following haloperidol administration was for a period of 1 h, whereas a testing period of 30 min was used for the analyses following acute clozapine treatment as this interval was sufficient to demonstrate the effect.

Drug Preparation and Administration

Clozapine, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (cat. no. C-6305; St Louis, MO), was dissolved in 1.2 N HCl, diluted to a concentration of 2 mg/ml in sterile water, and stored in aliquots at −20°C. Haloperidol, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (cat. no. H-1512; St Louis, MO), was dissolved in 20 μl acetic acid, diluted in sterile water, brought to pH 6.5 with addition of 1 M NaOH, and further diluted in sterile PBS to a stock concentration of 0.3 mg/ml and stored in aliquots at −20°C. Aliquots of each drug were thawed at 37°C on the day of use, and diluted to their final concentration in PBS to achieve a final pH of 6.5–7. Vehicle was prepared in an identical manner without addition of drug. Drug or vehicle was administered via intraperitoneal injection in a 10 ml/kg volume. For studies of acute response to clozapine, drug was administered at doses of 1, 3.5, or 7 mg/kg 20 min before the onset of testing. For chronic injection studies, animals were injected with drug daily on 6 out of 7 days, for a period of 15 days. In no case did the injection-free day precede the day of testing. Animals received 3.5 mg/kg/day for the first week of treatment, followed by 7 mg/kg/day for the second week. Testing was performed 24 h after the final 7 mg/kg dose, to avoid acute sedation affecting performance. In addition, on the day of testing animals were treated with a single 1 mg/kg dose of clozapine 20 min before testing to facilitate comparison to the acute dosing condition. Equal numbers of Egr3–/– and WT littermate animals, as well as drug- and vehicle-treated animals, were evaluated on each day of testing.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Chicago, IL) and Systat (Point Richmond, CA) programs to conduct t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and repeated measures ANOVA as appropriate. For ANOVAs with repeated measures, the Huynh–Feldt adjustment of degrees of freedom was used for all within-subjects (repeated measures) effects containing more than two levels to generate corrected ‘p’ values to help protect against violations of the sphericity/compound symmetry assumptions underlying this ANOVA model.

RESULTS

Loss of Egr3 Results in Aggressive Behavior

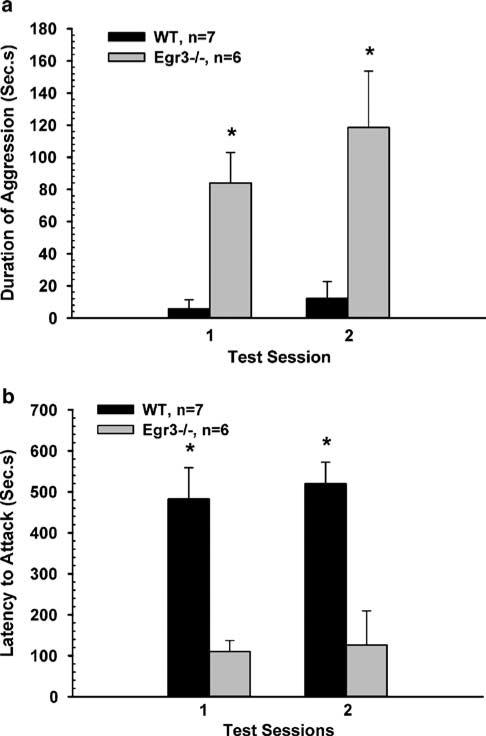

To test the hypothesis that Egr3–/– mice have an accentuated response to a socially stressful situation, we examined the performance of Egr3–/– mice in the resident-intruder model (Crawley, 2000). Egr3–/– mice showed 8–10 times greater duration of aggression in a 10 min test period than WT littermate controls (repeated measures ANOVA, p<0.001; Figure 1a, and Supplementary Figure S1). Egr3–/– mice also displayed a decreased latency before initiating an attack on the intruder mice (repeated measures ANOVA, p=0.001; Figure 1b), suggesting that they were more impulsive than their WT littermates (Saudou et al, 1994; Bouwknecht et al, 2001).

Figure 1.

Egr3–/– mice display heightened aggressive behavior. In the resident–intruder test, (a) Egr3–/– mice showed significantly increased aggressive behavior toward a foreign intruder compared to WT mice on two separate test sessions spaced several days apart. An ANOVA with repeated measures on total duration of aggression yielded a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,11)=29.40, p<0.001). Separate pairwise comparisons (t-tests) showed that Egr3–/– mice were significantly (*) more aggressive than controls on each test day (p=0.001 and p=0.010). (b) Egr3–/– mice also showed a significantly decreased latency to attack the intruder. An ANOVA with repeated measures showed a main effect of genotype (F(1,11)=20.33, p=0.001). Separate t-tests comparing Egr3–/– mice to WT controls on each test day were also significant (*) (p=0.001 and 0.002, respectively).

Regional Changes in Serotonergic and Dopaminergic Systems

Altered function of the 5-HT and DA systems has been associated with increased aggression in mice and humans (Hen, 1996; Miczek et al, 2002; Gordon and Hen, 2004; Popova, 2006). In animal models, manipulations of serotonin result in changes in aggression, and inactivation of 5HT-1B receptors in mice results in increased impulsive aggression (Saudou et al, 1994; Bouwknecht et al, 2001). Altered cerebrospinal fluid levels of serotonin metabolites have been associated with impulsive violent behavior in humans (Oquendo and Mann, 2000). Disruption of the gene for monamine oxidase A, an enzyme that degrades 5-HT and DA, is associated with violent behavior in humans (Brunner et al, 1993) and animals (Hen, 1996; Miczek et al, 2002) and dopaminergic manipulations also influence impulsive aggression in both humans and animals (Miczek et al, 2002). We therefore, decided to investigate levels of these neurotransmitters and their metabolites in the brains of Egr3–/– mice to evaluate whether abnormalities in the serotonergic or dopaminergic systems may contribute to the aggressive behavior of these mice.

We used high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to examine the levels of these neurotransmitters in three brain regions: the amygdala, which has been implicated in the regulation of aggressive behavior (Nelson and Chiavegatto, 2001), the hypothalamus, which regulates release of stress and sex hormones that may influence aggressive behavior, and the hippocampus, which plays an essential role in encoding new memories and regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis through innervation of the hypothalamus (Jacobson and Sapolsky, 1991). We used HPLC to determine neurotransmitter levels. We found a 25% increase in levels of the 5-HT metabolite 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) in the hippocampus of Egr3–/– mice compared with controls (p=0.048; Table 1), suggesting an increase in 5-HT turnover in this region. 5-HIAA levels did not differ between Egr3–/– and control mice in the hypothalamus or amygdala. Levels of DA in the hypothalamus were modestly elevated in Egr3–/– mice compared with WT controls (p=0.036; Table 1). Levels of DA did not differ between Egr3–/– and littermate control mice in the hippocampus or amygdala (Table 1). We found no differences in the level of 5-HT, DA, or their metabolites in the amygdala of Egr3–/– and WT mice (Table 1). Levels of 5-HT, or of the DA metabolites HVA, or DOPAC, did not differ in any of the three brain regions tested (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean Concentration (pg/mg Tissue)

| Molecule | Brain region | WT | Egr3–/– | SEM WT | SEM Egr3–/– | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT | Hippocampus | 267.8 | 301.6 | 13.2 | 27.7 | 0.297 |

| Amygdala | 226.6 | 212.0 | 16.7 | 33.5 | 0.706 | |

| Hypothalamus | 373.5 | 341.3 | 21.2 | 27.4 | 0.374 | |

| 5-HIAA | Hippocampus | 336.0 | 419.1 | 21.2 | 30.1 | 0.048 |

| Amygdala | 248.9 | 266.1 | 22.8 | 25.4 | 0.624 | |

| Hypothalamus | 355.6 | 384.2 | 23.5 | 27.3 | 0.445 | |

| DA | Hippocampus | 17.7 | 19.0 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 0.748 |

| Amygdala | 374.1 | 368.5 | 42.4 | 57.8 | 0.940 | |

| Hypothalamus | 227.1 | 267.0 | 9.8 | 13.2 | 0.036 | |

| DOPAC | Hippocampus | 17.9 | 17.3 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 0.898 |

| Amygdala | 89.1 | 93.8 | 9.4 | 7.0 | 0.695 | |

| Hypothalamus | 105.3 | 131.0 | 12.5 | 5.1 | 0.086 | |

| HVA | Hippocampus | 134.1 | 106.3 | 10.7 | 17.2 | 0.202 |

| Amygdala | 162.1 | 154.9 | 21.7 | 18.4 | 0.805 | |

| Hypothalamus | 213.9 | 255.8 | 11.0 | 17.0 | 0.065 |

5-HT, serotonin; 5-HIAA, 5-Hydroxyindole Acetic Acid; DA, dopamine; DOPAC, 3, 4 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; HVA, homovanillic acid; SEM, standard error of the mean.

p-Values <0.05 are indicated in bold.

The Effect of Low Dose Clozapine on Aggression in Egr3–/– Mice

To determine the possible utility of Egr3–/– mice for studying human psychiatric conditions and assessing efficacy of therapeutic agents, we next evaluated whether the aggressive behavior of Egr3–/– mice could be reversed by an antipsychotic medication that has been demonstrated to reduce aggressive behavior in humans (Hector, 1998; Chalasani et al, 2001; Chengappa et al, 2002; Krakowski et al, 2006). We used clozapine for this purpose since it was recently shown to be superior to other antipsychotics in reducing aggressive behavior in psychiatrically ill individuals (Krakowski et al, 2006).

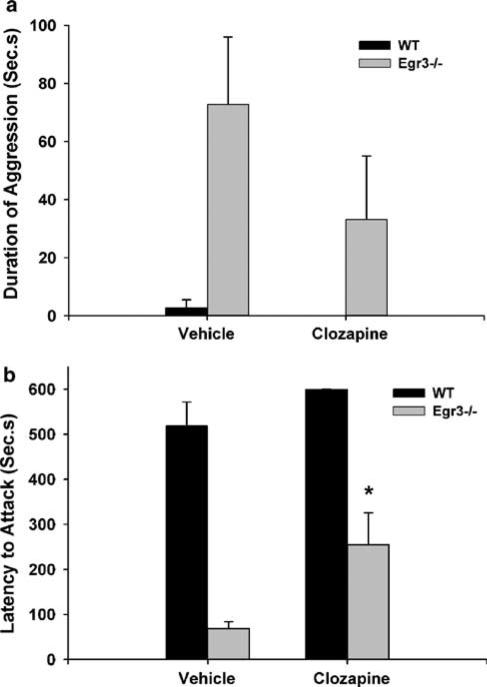

We began by testing the effects of an acute low dose of clozapine (1 mg/kg) administered 25 min before testing the aggressive behavior of Egr3–/– and WT mice (Figure 2). We found that this treatment did not significantly affect the total duration of aggressive behaviors displayed by the resident mice (ANOVA, p=0.181; Figure 2a). Although clozapine-treated Egr3–/– mice showed a trend toward decreased duration of aggression compared to vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.084; Figure 2a). Likewise, this dose of clozapine also did not affect the aggressive behavior of WT mice (comparison between vehicle- and clozapine-treated WT mice were not statistically significant; p=0.9).

Figure 2.

Acute low dose clozapine treatment reduces impulsivity in Egr3–/– mice but not overall aggression. (a) Analysis of total duration of aggressive behavior following acute administration of 1 mg/kg clozapine or vehicle to WT and Egr3–/– mice demonstrated a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,33)=11.04, p=0.002), but not of drug (F(1,33)=1.865, p=0.181). Individual comparison between Egr3–/– mice receiving vehicle and those receiving clozapine showed a trend toward decreased total duration of aggressive behavior that was not statistically significant (p=0.084). (b) However, 1 mg/kg clozapine significantly increased the latency to attack in Egr3–/– mice. (An ANOVA of latency to attack indicated a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,33)=84.78, p<0.001), and of drug (F(1,33)=9.632, p<0.004). Individual t-tests comparing clozapine vs vehicle-treated mice within each genotype showed that clozapine-treated Egr3–/– mice had significantly longer attack latencies relative to vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice (F(1,33)=9.09, *p=0.005), while the drug had no significant effect on the attack latencies of the WT littermate controls.) (n=9 for each: Egr3–/– vehicle-treated, WT-vehicle treated, Egr3–/– clozapine-treated mice; mice). n=10 WT clozapine-treated

In contrast to its lack of effect on the total duration of aggressive attacks, the acute administration of 1 mg/kg clozapine significantly increased the amount of time that passed before the resident mice attacked a novel intruder (ANOVA, p<0.001; Figure 2b). This measure, called the ‘latency to attack’, has been associated with impulsivity in related studies (Saudou et al, 1994; Bouwknecht et al, 2001). Thus clozapine may reduce the impulsivity of Egr3–/– mice. This effect in the clozapine-treated Egr3–/– animals was due to a longer latency to attack compared to vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice (p=0.005) clozapine had no discernible effect in WT animals (p=0.185). The lack of an effect of clozapine in WT animals suggests that its effect in the Egr3 mutants is not likely due to a non-specific sedative effect.

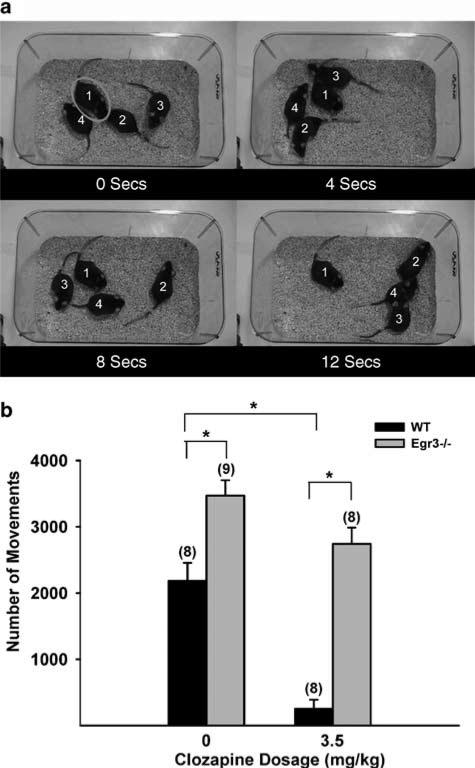

Egr3–/– Mice are Relatively Resistant to Sedation by Clozapine

Since the 1 mg/kg dose was insufficient to inhibit the duration of aggressive behavior we decided to test higher doses of clozapine. However, because clozapine can cause a number of side effects, including sedation, we examined the effect of higher doses on a pilot group of mice before testing a large group. We began by administering a dose of 3.5 mg/ kg clozapine (a subtherapeutic dose in humans). Visual inspection of the mice showed that this dose severely impaired the movement of WT mice (Figure 3a, and Supplementary Figure S2). They were able to move when nudged, but usually did not move in response to being sniffed or stepped upon by their cagemates (Supplementary Figure S2). In contrast, we were surprised to find that the movement of Egr3–/– mice was not visibly altered by this dose of clozapine (Figure 3a, and Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Acute higher-dose clozapine administration affects Egr3–/– mice in a manner different than WT mice. (a) Frames from a videotape of Egr3–/– and WT control mice following administration of either vehicle or 3.5 mg/kg clozapine show that this dose of clozapine produces immobility in WT mouse #1(circled). In contrast, the activity of an Egr3–/– mouse that has received 3.5 mg/kg of clozapine (#4), is not obviously distinguishable from WT or Egr3–/– mice that have received vehicle (#2 and #3, respectively). (See also Supplementary Figure S2 for video of response to 3.5 mg/kg, and Supplementary Figure S3 for response to 7 mg/kg). (b) Comparison of the effect of vehicle vs 3.5 mg/kg clozapine on the activity of Egr3–/– and WT littermate mice showed that clozapine affected Egr3–/– mice differently than WT mice (two-way ANOVA yielded a significant effect of genotype (F(1,29)=68.28, p<0.001), and of drug (F(1,29)=33.92, p<0.001), and a significant genotype by drug interaction (F(1,29)=6.96, p=0.013)). Individual t-tests indicated that vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice are significantly more active than vehicle-treated WT controls. In addition, while acute administration of 3.5 mg/kg of clozapine profoundly repressed activity in WT mice (compare WT vehicle to WT clozapine 3.5 mg/kg), Egr3–/– mice remained as active as vehicle-treated WT mice following this dose of clozapine (*p<0.001; numbers in parentheses=n).

We then tested the effect of 7 mg/kg of clozapine, a dose still within the typical range used in rodent studies in the literature. WT mice appeared severely sedated by this dose of clozapine (Supplementary Figure S3). They lay immobile with their legs splayed and their bellies on the bedding of the cage. The sedation persisted for up to 3 h following administration of the drug, though the mice could be induced to move when the cage was tipped (Supplementary Figure S3, part b). Again, Egr3–/– mice were not obviously affected by the clozapine. Following a 7 mg/kg dose they ambulated throughout the cage in a manner visibly indistinguishable from their vehicle-treated Egr3–/– litter-mates (Supplementary Figure S3, part a). This relative insensitivity to the sedating effects of clozapine in Egr3–/– mice persisted for more than 2 h following administration of the drug (Supplementary Figure S3, part a). When observed intermittently in subsequent hours after administration at no time did the Egr3–/– mice display the sedated appearance of clozapine-treated WT mice, indicating that this was not simply a delay in the effect of the drug on Egr3–/– mice.

To document this difference in the response of Egr3–/– and WT mice to higher-dose clozapine, we treated a cohort of mice with either vehicle or 3.5 mg/kg of clozapine and measured total movements for a 30 min period using the open field activity test. Figure 4b shows the combined results of vehicle vs clozapine treatment on the activity of Egr3–/– and WT littermate mice.

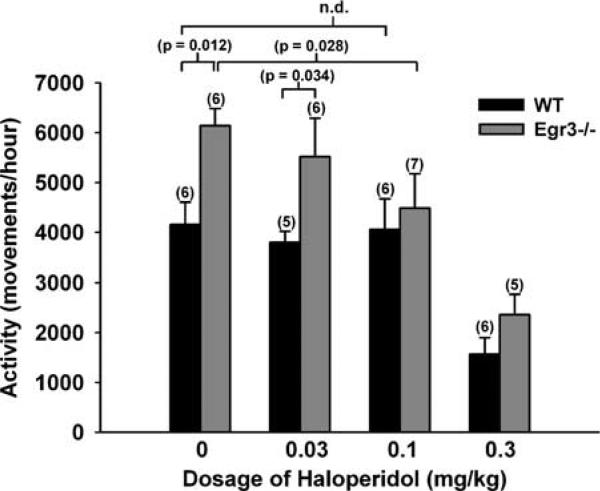

Figure 4.

Acute haloperidol administration reduces the hyperactivity of Egr3–/– mice in a dose-dependent fashion. An overall ANOVA showed a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,39)=10.48, p=0.002) and a significant main effect of dose (F(3,39)=13.16, p<0.005). A one-way ANOVA across all Egr3–/– mice demonstrated a significant effect of haloperidol (p=0.003) and a pairwise comparison showed that a dose of 0.1 mg/kg was sufficient to reduced activity of Egr3–/– mice (p=0.028). A one way ANOVA across all WT mice demonstrated that haloperidol significantly reduced activity in controls (p=0.001), but a pairwise comparison demonstrated that 0.1 mg/kg did not affect activity in WT mice (p=0.897) (n.d.—not different. Single-digit numbers in parentheses=n).

This study showed two significant findings. First, the comparison of vehicle-treated mice demonstrated that Egr3–/– mice were 59% more active than WT mice (p<0.001). This replicated our previous studies indicating hyperactivity of untreated Egr3–/– mice compared to WT controls in this test of locomotor activity in a novel environment (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007). Second, this test demonstrated quantitatively that clozapine has different effects in Egr3–/– mice than in their WT littermates (ANOVA indicated a significant interaction of genotype and clozapine dose; p=0.013). Specifically, clozapine significantly inhibits activity in WT mice (p<0.001), and WT mice treated with either vehicle or clozapine showed significantly lower activity than that of Egr3–/– mice (p<0.001 for each comparison). These results support the visually evident difference in the response of Egr3–/– mice to clozapine (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S2) demonstrating a relative resistance of Egr3–/– mice to the sedating effects of clozapine compared to their WT littermates.

We next examined whether the first-generation (typical) antipsychotic haloperidol would also be effective in reversing the abnormal behavior of Egr3–/– mice. We compared the effect of acute administration of vehicle vs 3 doses of haloperidol (0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 mg/kg) on the activity of Egr3–/– and WT mice (Figure 4). We found that vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice are approximately 50% more active than their littermate controls, replicating our earlier finding of hyperactivity (Figure 3b, above and Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007) (p=0.012). A dose of 0.1 mg/kg of haloperidol significantly reduced the hyperactivity of Egr3–/– mice. Notably, this dose of haloperidol did not affect the activity of WT mice (p=0.897).

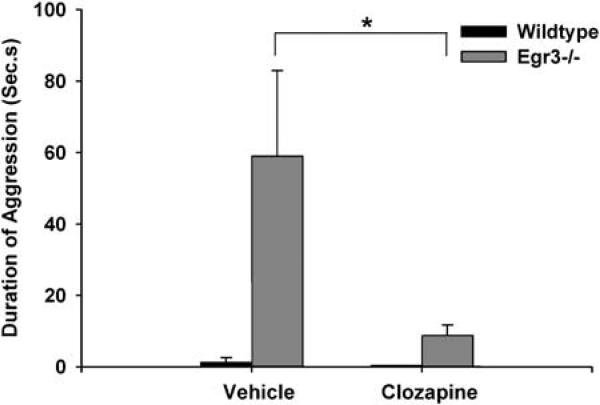

Chronic Clozapine Reduces Aggression in Egr3–/– Mice

Given the above results, we wanted to test whether a higher dosage of clozapine than 1 mg/kg would reduce the aggressive behavior of Egr3–/– mice. However, since even the 3.5 mg/kg dose produced acute sedation in the WT mice, we could not compare the effect of acute administration of clozapine on aggression in Egr3–/– and WT mice. We therefore decided to examine the effect of chronic clozapine administration. Notably, chronic administration more closely resembles effective usage of this medication in humans.

To limit the degree of sedation in WT mice we administered a lower dose of clozapine (3.5 mg/kg/day) for the first week, and then increased to 7.0 mg/kg/day for the second week. Mice were then tested in the resident intruder test of aggression 24 h after the last 7 mg/kg dose of clozapine to avoid acute sedating effects of the drug. We hypothesized that usage of higher dosages for 2 weeks should improve the likelihood that clinically relevant concentrations of clozapine were in the blood for a substantial amount of the inter-injection interval.

We found that chronic clozapine administration significantly reduced the total duration of aggressive behavior of Egr3–/– mice in the resident intruder test (p=0.005; Figure 5). The effect of chronic clozapine treatment on aggressive behavior in Egr3–/– mice was not likely to result from sedation since this dosing paradigm did not affect activity levels in these mice (not shown). Clozapine did not decrease the duration of aggression in the WT control mice (Figure 5); however, this could have been due to a floor effect since vehicle-treated WT mice displayed low levels of aggression.

Figure 5.

Two weeks of chronic clozapine administration significantly reduced the aggressive behavior of Egr3–/– mice. An ANOVA showed significant effects of genotype (F(1,40)=7.603, p=0.009), and treatment (F(1,40)=4.120, p=0.039), and a significant genotype by treatment interaction (F(1,40)=4.120, p=0.049), suggesting that the effects of chronic clozapine treatment on aggression were different in Egr3–/– mice than in their WT littermates. A subsequent t-test confirmed that Egr3–/– mice receiving chronic clozapine showed significantly less aggression than vehicle-treated Egr3–/– mice (*p=0.005) (n=9 for each: Egr3–/– vehicle-treated, WT-vehicle treated, Egr3–/– clozapine-treated mice; n=10 WT clozapine-treated mice).

DISCUSSION

Aggression in Egr3–/– Mice

Although numerous environmental and pharmacologic stimuli are known to activate expression of IEGs in the brain, demonstration of a functional role for these genes in the biological or behavioral responses to these stimuli has been lacking. We have previously found that Egr3–/– mice show an accentuated response, and abnormal habituation, to stress and novelty. In addition, we reported that Egr3–/– mice showed persistent olfactory-based investigatory beha vior toward familiar conspecifics that showed little habituation and was intrusive to the degree that it appeared to disrupt normal social interactions (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007). To explore further these phenomena, we chose to combine these stimuli in the current study and examine the response of Egr3–/– mice to a novel stressful social stimulus using the resident–intruder paradigm. We found that Egr3–/– mice engage in extended bouts of aggression and show a decreased latency to attack the intruder mouse. These findings are consistent with the other heightened stress responses we have found in Egr3–/– mice (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007).

This combination of abnormal social investigation of familiar mice, and increased aggression toward, and a decreased latency to attack, a foreign mouse, have been reported in mice lacking the 5-HT1B receptor (Saudou et al, 1994; Bouwknecht et al, 2001). The authors of these studies interpreted these results to indicate impaired impulse control in 5-HT1B knockout mice, a label which aptly describes the combination of behaviors displayed by Egr3–/– mice (Brunner and Hen, 1997).

The heightened aggressive behavior of 5-HT1B–/– mice is one of many findings in both animals and humans that support a role for the 5-HT system in regulating aggressive behavior (Hen, 1996; Oquendo and Mann, 2000; Popova, 2006). Our finding of increased 5-HIAA in the hippocampus of Egr3–/– mice (Table 1) indicates an abnormality in 5-HT turnover, and suggests a possible mechanism through which Egr3 may be affecting aggressive and impulsive behavior. However, many of the human and non-human primate studies that report a correlation between cerebrospinal fluid 5-HIAA levels and aggression indicate that decreased levels of 5-HIAA are associated with increased aggression. Despite this general trend, there is significant variability in the experimental conditions and definitions of aggression used in these studies, and selective reporting of only positive findings may lead to the conclusion that these results are more uniform than is actually the case (see Krakowski, 2003 for review). Studies in mice have not resolved this issue, as various knockout mice that produce opposing effects on 5-HT function in the brain can show identical abnormalities in aggressive and anxiety-related behaviors (see Gordon and Hen, 2004 for review). The complicated nature of the 5-HT receptor system, with at least seven receptor classes identified to date (at least two of which have multiple subtypes), and locations on both preand post-synaptic fibers, makes it difficult to specify the mechanisms of action of the 5-HT system for any behavior. The numerous findings strongly support a role for 5-HT in aggressive behavior, but the specific mechanism underlying this relationship will take time to decipher.

The dopaminergic system has also been implicated in aggressive behavior (Miczek et al, 2002), and the major class of medications used to treat aggression are the antipsychotics, which share the characteristic of blocking DA D2 receptors. We found that DA levels were elevated in the hypothalamus of Egr3–/– mice. This finding is particularly intriguing as the neurons in this region control the release of pituitary hormones that modulate behavior as well as adrenal release of the stress hormone corticosterone (the latter of which we have found to be abnormally sensitive in Egr3–/– mice (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007)).

Egr3–/– Mice Demonstrate Separable Actions of Clozapine

Our finding of decreased sensitivity to the sedating effects of clozapine was unexpected. The mechanism underlying this effect is not clear. Since Egr3 functions as a transcription factor it seems reasonable that genes regulated by Egr3 may be required for some actions of clozapine. These may be genes coding for receptors to which clozapine binds, or for other molecules in the signaling pathway downstream of these receptors.

Despite this lack of sensitivity to its sedating effects, Egr3–/– mice respond to the anti-aggressive effects of clozapine. We found that chronic clozapine treatment significantly reduced the duration of aggressive attacks by Egr3–/– mice toward an unfamiliar ‘intruder’. This does not appear to be a result of sedation, as mice were tested 24 h after their last dose of medication at which time neither Egr3–/– nor WT mice treated with clozapine showed reduced activity compared with saline-treated controls. This result is consistent with the clinical effects of clozapine, which include a reduction of aggressive behavior in psychotic patients (Hector, 1998; Chalasani et al, 2001; Chengappa et al, 2002; Krakowski et al, 2006), and suggests that Egr3–/– mice are sensitive to at least some of the therapeutic effects of clozapine. Several studies have demonstrated clozapine to be more effective than other antipsychotic medications in treating aggressive behavior in schizophrenia patients (Buckley et al, 1995; Citrome et al, 2001; Volavka et al, 2004; Krakowski et al, 2006). Notably, one such study found that the anti-aggressive activity of clozapine was a separable effect from the sedating activity of clozapine (Krakowski et al, 2006).

Clozapine is differentiated from the earlier class of first-generation antipsychotic medications by its broader range of receptor binding activity, including its blockade of 5-HT receptors, relatively lower activity at D2-type DA receptors, and higher affinity for D4-type DA receptors, and activity at α1 and α2 norepinephrine receptors (Meltzer, 1992; Seeman et al, 1997; Miyamoto et al, 2005). This difference, together with the superior efficacy of clozapine in patients with treatment-resistant psychoses, spurred the development of second-generation (also called ‘atypical’) antipsychotic medications aimed at mimicking the receptor activity profile of clozapine. It is intriguing to consider whether the abnormalities we found in 5-HT turnover and in the DAergic systems in Egr3–/– mice, though limited in degree and regionality, may contribute to the differential response of Egr3–/– mice to clozapine. A systematic determination of the neurobiological abnormalities that result from loss of Egr3 should aid in distinguishing these two, separate, biological actions of clozapine, which would provide a framework for development of more targeted therapeutics for treating psychiatric conditions.

Haloperidol, a first-generation antipsychotic medication, was effective in reversing the hyperactivity of Egr3–/– mice. Interestingly, this was seen at doses that did not impair activity in WT mice. These data suggest that the reduction in activity of WT mice by clozapine may have a different etiology than the reduction of activity in response to haloperidol. The Egr3–/– mice demonstrate resistance to what appears to be sedation (WT mice are laying on the cage floor after 7 mg/kg clozapine). Mice that received haloperidol remain on their feet, but are simply less active, an effect that may result from extrapyramidal side effects of this drug.

Egr3 and Schizophrenia

We were struck by the similarity of our findings distinguishing the dual effects of clozapine in Egr3–/– mice with the effects of antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia patients. Patients with schizophrenia are able to tolerate doses of antipsychotic medications many times greater than those that can be tolerated by healthy control individuals, with significantly lower degrees of side effects (Cutler, 2001). Yet, they are responsive to the therapeutic effects of these medications. In fact, the greater risk of serious side effects, such as cardiovascular events, in healthy controls has led to the proposal that non-psychiatrically ill individuals should not be used in clinical studies of these medications (Cutler, 2001). This similarity suggested to us the possibility that loss of Egr3 may mimic some aspects of the illness schizophrenia.

In fact, a number of characteristics of Egr3–/– mice are consistent with animal models of schizophrenia. These include hyperactivity, an accentuated response and abnormal adaptation to novelty and stress, deficits in startle habituation, and defects in synaptic plasticity (which model the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia) (Gallitano-Mendel et al, 2007). The biological positioning of Egr3 also supports its potential role in this illness as Egr3 is activated downstream of several key proteins implicated in schizophrenia risk or pathogenesis. These include neuregulin 1 (NRG1) (Sweeney et al, 2001; Hippenmeyer et al, 2002; Jacobson et al, 2004), a gene showing genetic association with schizophrenia (Moises et al, 2002; Stefansson et al, 2002); calcineurin (CN) (Mittelstadt and Ashwell, 1998), a calcium calmodulin-dependent phosphatase implicated in schizophrenia risk based on studies of mutant mice as well as human genetic association studies (Gerber et al, 2003; Miyakawa et al, 2003); and N-methyl D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) (Yamagata et al, 1994), a receptor pathway implicated in schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Olney et al, 1999).

Further support for the potential involvement of Egr3 in the pathology of schizophrenia comes from recent studies, which found that the expression of Egr3 was significantly lower in the brains of schizophrenia patients compared to controls (Mexal et al, 2005; Yamada et al, 2007). The fact that the human Egr3 gene resides at the chromosomal location 8p21.3, which linkage analyses have identified as a major schizophrenia locus (Blouin et al, 1998; Kendler et al, 2000; Gurling et al, 2001; Lewis et al, 2003) highlights the potential for dysfunction of Egr3 to contribute to this disorder. In fact, polymorphisms in Egr3 were recently demonstrated to be associated with schizophrenia in a Japanese population (Yamada et al, 2007).

The various behavioral and pharmacologic abnormalities we have shown in Egr3–/– mice make this line of mice a particularly interesting and useful tool for further studies that may have relevance not only for understanding behaviors such as aggression, but also for understanding the mechanisms of action of clozapine, one of the leading antipsychotic agent available.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C Press for video processing and editing, T Hershey for graphics instruction, H Volk and M Jing for assistance with data analysis, and E Ren for assistance with the haloperidol study. We are grateful to N Farber and CR Cloninger for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01NS040745 (to JM), MH52220 (to EAP), Neuroscience Blueprint Core Grant NS057105 (to Washington University) and NRSA T32AA07580 (to AGM), as well as the Pfizer Fellowship in Biological Psychiatry (to AGM), a NARSAD/ Sidney R Baer Jr. Foundation Young Investigator Award (to AGM), and a Merit Review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to EAP).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that over the past three years Dr Gallitano-Mendel received a Grant from Pfizer Inc., ‘The Pfizer Fellowship in Biological Psychiatry’; and Dr Pehek has received compensation from Janssen Pharmaceutica. Dr Wozniak has no potential conflicts of interest to report. Dr Milbrandt and Dr Gallitano-Mendel have submitted a patent application on the line of mice used in this study.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

REFERENCES

- Artola A, von Frijtag JC, Fermont PC, Gispen WH, Schrama LH, Kamal A, et al. Long-lasting modulation of the induction of LTD and LTP in rat hippocampal CA1 by behavioural stress and environmental enrichment. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin JL, Dombroski BA, Nath SK, Lasseter VK, Wolyniec PS, Nestadt G, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q32 and 8p21. Nat Genet. 1998;20:70–73. doi: 10.1038/1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknecht JA, Hijzen TH, van der Gugten J, Maes RA, Hen R, Olivier B. Absence of 5-HT(1B) receptors is associated with impaired impulse control in male 5-HT(1B) knockout mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:557–568. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozon B, Davis S, Laroche S. Regulated transcription of the immediate-early gene Zif268: mechanisms and gene dosage-dependent function in synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Hippocampus. 2002;12:570–577. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozon B, Davis S, Laroche S. A requirement for the immediate early gene zif268 in reconsolidation of recognition memory after retrieval. Neuron. 2003;40:695–701. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunewell KH, Manahan-Vaughan D. Long-term depression: a cellular basis for learning? Rev Neurosci. 2001;12:121–140. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2001.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA. Stopwatch+ Center for Behavioral Neuro-science; PO Box 3966, Atlanta GA: 2002. p. 30302. http://www.cbn-atl.org/research/stopwatch.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D, Hen R. Insights into the neurobiology of impulsive behavior from serotonin receptor knockout mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;836:81–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, Ropers HH, van Oost BA. Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science. 1993;262:578–580. doi: 10.1126/science.8211186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley P, Bartell J, Donenwirth K, Lee S, Torigoe F, Schulz SC. Violence and schizophrenia: clozapine as a specific antiaggressive agent. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23:607–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani L, Kant R, Chengappa KN. Clozapine impact on clinical outcomes and aggression in severely ill adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:965–968. doi: 10.1177/070674370104601010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KN, Vasile J, Levine J, Ulrich R, Baker R, Gopalani A, et al. Clozapine: its impact on aggressive behavior among patients in a state psychiatric hospital. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, McEvoy J, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1510–1514. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.11.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J. What's Wrong with My Mouse? Behavioral Phenotyping of Transgenic and Knockout Mice. Wiley-Liss; New York: 2000. p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler NR. Pharmacokinetic studies of antipsychotics in healthy volunteers versus patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 5):10–13. discussion 23–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallitano-Mendel A, Izumi Y, Tokuda K, Zorumski CF, Boyle MP, Muglia L, et al. The immediate early gene Egr3 mediates adaptation to stress and novelty. Neuroscience. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.050. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber DJ, Hall D, Miyakawa T, Demars S, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M, et al. Evidence for association of schizophrenia with genetic variation in the 8p21.3 gene, PPP3CC, encoding the calcineurin gamma subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8993–8998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JA, Hen R. The serotonergic system and anxiety. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:27–40. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:1:027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurling HM, Kalsi G, Brynjolfson J, Sigmundsson T, Sherrington R, Mankoo BS, et al. Genomewide genetic linkage analysis confirms the presence of susceptibility loci for schizophrenia, on chromosomes 1q32.2, 5q33.2, and 8p21-22 and provides support for linkage to schizophrenia, on chromosomes 11q23.3-24 and 20q12.1-11.23. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:661–673. doi: 10.1086/318788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hector RI. The use of clozapine in the treatment of aggressive schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:466–472. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hen R. Mean genes. Neuron. 1996;16:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenmeyer S, Shneider NA, Birchmeier C, Burden SJ, Jessell TM, Arber S. A role for neuregulin1 signaling in muscle spindle differentiation. Neuron. 2002;36:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke KL, Ryan MJ, Wilczynski W. Social cues shift functional connectivity in the hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10712–10717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honkaniemi J, Zhang JS, Longo FM, Sharp FR. Stress induces zinc finger immediate early genes in the rat adrenal gland. Brain Res. 2000;877:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson C, Duggan D, Fischbach G. Neuregulin induces the expression of transcription factors and myosin heavy chains typical of muscle spindles in cultured human muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12218–12223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404240101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Sapolsky R. The role of the hippocampus in feedback regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:118–134. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-2-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MW, Errington ML, French PJ, Fine A, Bliss TV, Garel S, et al. A requirement for the immediate early gene Zif268 in the expression of late LTP and long-term memories. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:289–296. doi: 10.1038/85138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers JM, O'Neill FA, Martin R, Murphy B, MacLean CJ, et al. Clinical features of schizophrenia and linkage to chromosomes 5q, 6p, 8p, and 10p in the Irish Study of High-Density Schizophrenia Families. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:402–408. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Foy MR, Thompson RF. Behavioral stress modifies hippocampal plasticity through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4750–4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski M. Violence and serotonin: influence of impulse control, affect regulation, and social functioning. J Neuro-psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:294–305. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, Bark N, Cooper TB. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:622–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CM, Levinson DF, Wise LH, DeLisi LE, Straub RE, Hovatta I, et al. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:34–48. doi: 10.1086/376549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Carter J, Gao X, Whitehead J, Tourtellotte WG. The neuroplasticity-associated arc gene is a direct transcriptional target of early growth response (Egr) transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10286–10300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10286-10300.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D, Braunewell KH. Novelty acquisition is associated with induction of hippocampal long-term depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8739–8744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Diorio J, Francis D, Weaver S, Yau J, Chapman K, et al. Postnatal handling increases the expression of cAMP-inducible transcription factors in the rat hippocampus: the effects of thyroid hormones and serotonin. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3926–3935. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03926.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY. The importance of serotonin-dopamine interactions in the action of clozapine. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1992;17:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mexal S, Frank M, Berger R, Adams CE, Ross RG, Freedman R, et al. Differential modulation of gene expression in the NMDA postsynaptic density of schizophrenic and control smokers. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;139:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Fish EW, De Bold JF, De Almeida RM. Social and neural determinants of aggressive behavior: pharmacotherapeutic targets at serotonin, dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid systems. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:434–458. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstadt PR, Ashwell JD. Cyclosporin A-sensitive transcription factor Egr-3 regulates Fas ligand expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3744–3751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa T, Leiter LM, Gerber DJ, Gainetdinov RR, Sotnikova TD, Zeng H, et al. Conditional calcineurin knockout mice exhibit multiple abnormal behaviors related to schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8987–8992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432926100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Marx CE, Lieberman JA. Treatments for schizophrenia: a critical review of pharmacology and mechanisms of action of antipsychotic drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:79–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moises HW, Zoega T, Gottesman I. The glial growth factors deficiency and synaptic destabilization hypothesis of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Chiavegatto S. Molecular basis of aggression. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:713–719. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Kosofsky BE, Birnbaum R, Cohen BM, Hyman SE. Differential expression of c-fos and zif268 in rat striatum after haloperidol, clozapine, and amphetamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4270–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M, Numan MJ, Marzella SR, Palumbo A. Expression of c-fos, fos B, and egr-1 in the medial preoptic area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during maternal behavior in rats. Brain Res. 1998;792:348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan KJ, Wilkens EP, Baraban JM. Sequential expression of Egr-1 and Egr-3 in hippocampal granule cells following electroconvulsive stimulation. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1241–1248. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70031241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Newcomer JW, Farber NB. NMDA receptor hypofunction model of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33:523–533. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. The biology of impulsivity and suicidality. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;23:11–25. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehek EA, Crock R, Yamamoto BK. Selective subregional dopamine depletions in the rat caudate-putamen following nigrostriatal lesions. Synapse. 1992;10:317–325. doi: 10.1002/syn.890100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova NK. From genes to aggressive behavior: the role of serotonergic system. Bioessays. 2006;28:495–503. doi: 10.1002/bies.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudou F, Amara DA, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Ramboz S, Segu L, et al. Enhanced aggressive behavior in mice lacking 5-HT1B receptor. Science. 1994;265:1875–1878. doi: 10.1126/science.8091214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ML, Wong ST, Wozniak DF, Muglia LM, Liauw JA, Zhuo M, et al. Altered stress-induced anxiety in adenylyl cyclase type VIII-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4809–4820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04809.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Corbett R, Van Tol HH. Atypical neuroleptics have low affinity for dopamine D2 receptors or are selective for D4 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:93–110. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00187-X. discussion 111–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senba E, Ueyama T. Stress-induced expression of immediate early genes in the brain and peripheral organs of the rat. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:183–207. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, et al. Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:877–892. doi: 10.1086/342734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney C, Fambrough D, Huard C, Diamonti AJ, Lander ES, Cantley LC, et al. Growth factor-specific signaling pathway stimulation and gene expression mediated by ErbB receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22685–22698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourtellotte WG, Milbrandt J. Sensory ataxia and muscle spindle agenesis in mice lacking the transcription factor Egr3. Nat Genet. 1998;20:87–91. doi: 10.1038/1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:225–228. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000117424.05703.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Anwyl R, Rowan MJ. Behavioural stress facilitates the induction of long-term depression in the hippocampus. Nature. 1997;387:497–500. doi: 10.1038/387497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Gerber DJ, Iwayama Y, Ohnishi T, Ohba H, Toyota T, et al. Genetic analysis of the calcineurin pathway identifies members of the EGR gene family, specifically EGR3, as potential susceptibility candidates in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2815–2820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610765104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K, Kaufmann WE, Lanahan A, Papapavlou M, Barnes CA, Andreasson KI, et al. Egr3/Pilot, a zinc finger transcription factor, is rapidly regulated by activity in brain neurons and colocalizes with Egr1/zif268. Learn Mem. 1994;1:140–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.