Abstract

Background and Purpose

Cannabidiol has been reported to act as an antagonist at cannabinoid CB1 receptors. We hypothesized that cannabidiol would inhibit cannabinoid agonist activity through negative allosteric modulation of CB1 receptors.

Experimental Approach

Internalization of CB1 receptors, arrestin2 recruitment, and PLCβ3 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, were quantified in HEK 293A cells heterologously expressing CB1 receptors and in the STHdh Q7/Q7 cell model of striatal neurons endogenously expressing CB1 receptors. Cells were treated with 2‐arachidonylglycerol or Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol alone and in combination with different concentrations of cannabidiol.

Key Results

Cannabidiol reduced the efficacy and potency of 2‐arachidonylglycerol and Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol on PLCβ3‐ and ERK1/2‐dependent signalling in cells heterologously (HEK 293A) or endogenously (STHdh Q7/Q7) expressing CB1 receptors. By reducing arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 receptors, cannabidiol treatment prevented internalization of these receptors. The allosteric activity of cannabidiol depended upon polar residues being present at positions 98 and 107 in the extracellular amino terminus of the CB1 receptor.

Conclusions and Implications

Cannabidiol behaved as a non‐competitive negative allosteric modulator of CB1 receptors. Allosteric modulation, in conjunction with effects not mediated by CB1 receptors, may explain the in vivo effects of cannabidiol. Allosteric modulators of CB1 receptors have the potential to treat CNS and peripheral disorders while avoiding the adverse effects associated with orthosteric agonism or antagonism of these receptors.

Abbreviations

- 2‐AG

2‐arachidonyl glycerol

- BRETEff

BRET efficiency

- CBD

cannabidiol

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- THC

Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| GPCRs |

| CB1 receptors |

| CB2 receptors |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

The majority of available drugs that target GPCRs act at the receptor's orthosteric site – the site at which the endogenous ligand binds (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002). The cannabinoid CB1 receptor is the most abundant GPCR in the central nervous system and is expressed throughout the periphery (reviewed in Ross, 2007; Pertwee, 2008). Orthosteric ligands of CB1 receptors have been proposed as possible treatments for anxiety and depression, epilepsy, neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington disease and Parkinson disease, and chronic pain (Pertwee, 2008; Piscitelli et al., 2012) and have been tested in the treatment of addiction, obesity and diabetes (Pertwee, 2008; Piscitelli et al., 2012). Despite their therapeutic potential, orthosteric agonists of CB1 receptors are limited by their potential psychomimetic effects while orthosteric antagonists of CB1 receptors are limited by their depressant effects (Ross, 2007).

An allosteric binding site is a distinct domain from the orthosteric site that can bind to small molecules or other proteins in order to modulate receptor activity (Wootten et al., 2013). All class A, B and C GPCRs investigated to date possess allosteric binding sites (Wootten et al., 2013). Ligands that bind to receptor allosteric sites may be classified as allosteric agonists that can activate a receptor independent of other ligands, allosteric modulators that alter the potency and efficacy of the orthosteric ligand but cannot activate the receptor alone and mixed agonist/modulator ligands. As therapeutic agents, allosteric modulators, unlike allosteric agonists and mixed agonist/modulator ligands, are attractive because they lack intrinsic efficacy. Therefore, the effect ceiling of an allosteric modulator is determined by the endogenous or exogenous orthosteric ligand (Wootten et al., 2013). In contrast, exogenous orthosteric ligands may produce adverse effects through supraphysiological over‐activation or down‐regulation of a receptor (Wootten et al., 2013). Unlike orthosteric ligands, allosteric modulators of CB1 receptors may not produce these undesirable side effects because their efficacy depends on the presence of orthosteric ligands, such as the two major endocannabinoids, anandamide and 2‐arachidonylglycerol (2‐AG) (Ross, 2007; Wootten et al., 2013).

To date, the best‐characterized allosteric modulators of CB1 receptors are the positive allosteric modulator lipoxin A4 (Pamplona et al., 2012) and the negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 (Price et al., 2005; Horswill et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011; Ahn et al., 2013). ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 reduce the efficacy and potency of the CB1 receptor agonists WIN55,212‐2 and CP55,940 to stimulate GTPγS35, enhance Gαi/o‐dependent signalling and arrestin recruitment and inhibit CB1 receptor internalization and cAMP accumulation at submicromolar concentrations (Price et al., 2005; Horswill et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011; Ahn et al., 2013; Cawston et al., 2013). The well‐characterized NAM activities of ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 are the standards against which new possible CB1 receptor NAMs can be assessed.

The phytocannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD) is known to modulate the activity of many cellular effectors, including CB1 and CB2 receptors (Hayakawa et al., 2008), 5HT1A receptors (Russo et al., 2005), GPR55 (Ryberg et al., 2007), the μ‐ and δ‐opioid receptors (Kathmann et al., 2006), the TRPV1 cation channels (Bisogno et al., 2001), PPARγ (Campos et al., 2012) and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) (Bisogno et al., 2001). With regard to cannabinoid receptor‐specific effects, several in vitro and in vivo studies have reported that CBD acts as an antagonist of cannabinoid agonists at CB1 receptors at concentrations well below the reported affinity (Ki) for CBD to the orthosteric agonist site of these receptors (Pertwee et al., 2002; Ryan et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2007; McPartland et al., 2014). We recently reported that the effects of CBD on intracellular signalling were largely independent of CB1 receptors (Laprairie et al., 2014a). However, CBD inhibited internalization of CB1 receptors in vitro at submicromolar concentrations where no other CB1 receptor‐dependent effect on signalling was observed (Laprairie et al., 2014a). Because ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 are also known to inhibit CB1 receptor internalization and taking into account earlier in vivo data suggesting that CBD can act as a potent antagonist at CB1 receptors, we hypothesized that CBD could have NAM activity at CB1 receptors.

Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether CBD acted as a NAM at CB1 receptors in vitro. The NAM activity of CBD was tested for arrestin, Gαq (PLCβ3) and Gαi/o (ERK1/2) pathways using 2‐AG and Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) as the orthosteric probes and compared with the competitive antagonist O‐2050 (Hudson et al., 2010; Laprairie et al., 2014a). While some studies have suggested that O‐2050 may be a partial agonist of CB1 receptors (Wiley et al., 2011, 2012), several groups have noted the competitive antagonist activity of O‐2050 at these receptors (Canals and Milligan, 2008; Higuchi et al., 2010; Ferreira et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2013). Allosteric effects of CBD were studied using an operational model of allosterism (Keov et al., 2011). Using this operational model, we were able to estimate ligand co‐operativity (α), changes in efficacy (β) and orthosteric and allosteric ligand affinity (K A and K B) (Keov et al., 2011) and to test our hypothesis that CBD displayed NAM activity at CB1 receptors. HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were used as model systems. Because HEK 293A cells represent a well‐characterized heterologous expression system to study CB1 receptor signalling. STHdh Q7/Q7 cells model the major output of the indirect motor pathway of the striatum where CB1 receptor levels are highest, relative to other regions of the brain (Trettel et al., 2000; Laprairie et al., 2013, 2014a), making this cell line ideally suited to studying endocannabinoid signalling in a more physiologically relevant context.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK 293A cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manaassas, VI, USA). Cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 104 U∙mL−1 Pen/Strep. STHdh Q7/Q7 cells are derived from the conditionally immortalized striatal progenitor cells of embryonic day 14 C57BL/6J mice (Coriell Institute, Camden, NJ, USA) (Trettel et al., 2000). Cells were maintained at 33°C, 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l‐glutamine, 104 U∙mL−1 Pen/Strep and 400 µg∙mL−1 geneticin. Cells were serum‐deprived for 24 h prior to experiments to promote differentiation (Trettel et al., 2000; Laprairie et al., 2013, 2014a,2014b).

Plasmids and transfection

Human CB1, CB1A, CB1B receptors and arrestin2 (β‐arrestin1) were cloned and expressed as either green fluorescent protein2 (GFP2) or Renilla luciferase II (Rluc) fusion proteins. CB1‐GFP2 and arrestin2‐Rluc were generated using the pGFP2‐N3 and pcDNA3.1 plasmids (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) as described previously (Hudson et al., 2010; Laprairie et al., 2014a). The GFP2‐Rluc fusion construct and Rluc plasmids have been previously described (Laprairie et al., 2014a).

The human CB1 receptor was mutated at two cysteine residues (Cys98 and Cys107). Mutagenesis was conducted as described previously (Laprairie et al. 2013) with the cysteine residues being mutated to alanine (C98A and C107A) or to serine (C98S and C107S) using the CB1‐GFP2 fusion plasmid and the following forward and reverse primers: CB1 C98A‐GFP2 forward 5′‐AACATCCAGGCTGGGGAGAACT‐3′, reverse 5′‐AGTTCTCCCCAGCCTGGATGTT‐3′; and CB1 C107A‐GFP2 forward 5′‐GACATAGAGGCTTTCATGGTC‐3′, reverse 5′‐GACCATGAAAGCCTCTATGTC‐3′; CB1 C98S‐GFP2 forward 5′‐AACATCCAGTCTGGGGAGAACT‐3′, reverse 5′‐AGTTCTCCCCAGACTGGATGTT‐3′; and CB1 C107S‐GFP2 forward 5′‐GACATAGAGTCTTTCATGGTC‐3′, reverse 5′‐GACCATGAAAGACTCTATGTC‐3′.

Mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing (GeneWiz, Camden, NJ, USA).

Cells were grown in six‐well plates and transfected with 200 ng of the Rluc fusion plasmid and 400 ng of the GFP2 fusion plasmid according to previously described protocols (Laprairie et al., 2014a) using Lipofectamine 2000® according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada). Transfected cells were maintained for 48 h prior to experimentation.

BRET2

Interactions between CB1 and arrestin2 were quantified via BRET2 according to previously described methods (Laprairie et al., 2014a). BRET efficiency (BRETEff) was determined as previously described (James et al., 2006; Laprairie et al., 2014a) such that Rluc alone was used to calculate BRETMIN and the Rluc‐GFP2 fusion protein was used to calculate BRETMAX.

On‐cell™ and In‐cell™ Western

On‐cell Western analyses were completed as described previously (Laprairie et al., 2014a) using primary antibody directed against N‐CB1 receptors (1:500; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Cat No. 101500). All experiments measuring CB1 receptors included an N‐CB1 blocking peptide control (1:500; Cayman Chemical Company), which was incubated with N‐CB1 antibody (1:500). Immunofluorescence observed with the N‐CB1 blocking peptide was subtracted from all experimental replicates. In‐cell Western analyses were conducted as described previously (Laprairie et al., 2014a). Primary antibody solutions were as follows: N‐CB1 (1:500), pERK1/2(Tyr205/185) (1:200), ERK1/2 (1:200), pPLCβ3(S537) (1:500), PLCβ3 (1:1000) or β‐actin (1:2000) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Secondary antibody solutions were as follows: IRCW700dye or IRCW800dye (1:500; Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Quantification was completed using the Odyssey Imaging system and software (v. 3.0; Li‐Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Data analysis and curve fitting

Data are presented as the mean ± the SEM or mean and 95% confidence interval, as indicated, from at least four independent experiments. All data analysis and curve fitting were carried out using GraphPad (v. 5.0) (Prism; La Jolla, CA). Concentration–response curves (CRCs) were fit with the nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters), Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift model or operational model of allosterism (equation (1)) (Keov et al., 2011) and are shown in each figure according to the best‐fit model as determined by R 2 value (GraphPad Prism v. 5.0). Pharmacological statistics were obtained from nonlinear regression models as indicated in figures and tables. Global curve fitting of allosterism data was carried out using the following operational model (Keov et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011; Hudson et al., 2014):

| (1) |

where E is the measured response, A and B are the orthosteric and allosteric ligand concentrations, respectively; E max is the maximum system response; α is a measure of the allosteric co‐operativity on ligand binding; β is a measure of the allosteric effect on efficacy; K A and K B are estimates of the binding of the orthosteric and allosteric ligands, respectively; n represents the Hill slope; and τA and τB represent the abilities of the orthosteric and allosteric ligands to directly activate the receptor (Smith et al., 2011). To fit experimental data to this equation, E max and n were constrained to 1.0 and 1.0, respectively, which allowed for estimates of α, β, K A, K B, τA and τB.

Relative receptor activity (RA) was calculated according to equation (2) (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002):

| (2) |

where E max % is the E max of the CRC in the presence of a given concentration of CBD, EC50 is the EC50 (μM) in the presence of a given concentration of CBD, E max Agonist Alone % is the E max in the absence of CBD and EC50 Agonist Alone is the EC50 (μM) in the absence of CBD. Statistical analyses were one‐way or two‐way ANOVA, as indicated, using GraphPad. Post hoc analyses were performed using Dunnett's multiple comparisons as well as Bonferroni's or Tukey's test, as indicated. Homogeneity of variance was confirmed using Bartlett's test. The level of significance was set to P < 0.001 or P < 0.01, as indicated. To improve the readability of the data, figures have been laid out where possible such that data from HEK 293A cells appear above data from STHdh Q7/Q7 cells and data for O‐2050 appear before data for CBD (Figures 2, 3, 4).

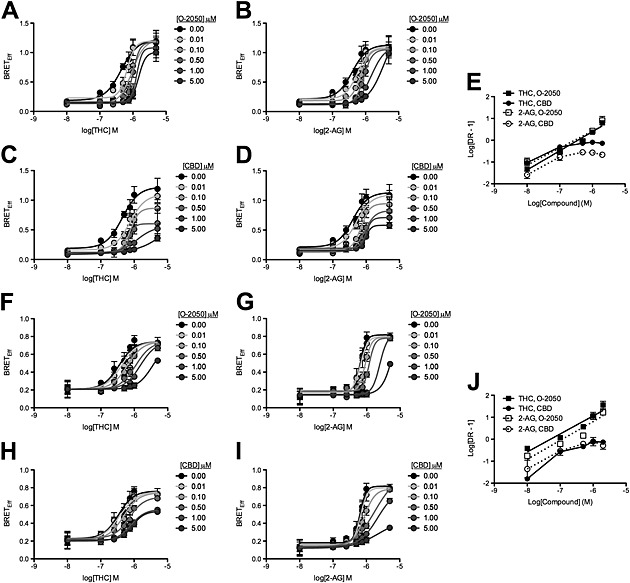

Figure 2.

CBD was a NAM of arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 receptors following THC and 2‐AG treatment. HEK 293A (A–E) and STHdh Q7/Q7 (F–J) cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐containing and CB1‐GFP2‐containing plasmids, and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with 2‐AG or THC ± O‐2050 or CBD. CRCs were fit using Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift (A, B, F and G) and operational model of allosterism (C, D, H and I) nonlinear regression models. (E and J) Schild regressions were plotted as the logarithm of 2‐AG or THC dose against the logarithm of the dose–response at EC50 – 1. N = 6.

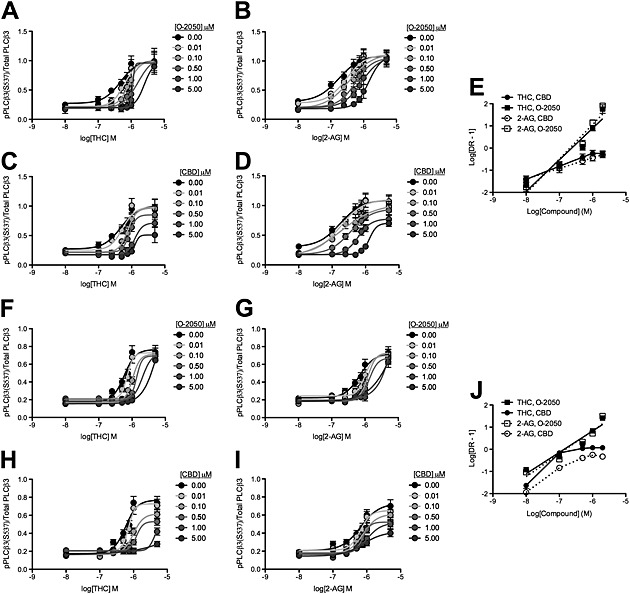

Figure 3.

CBD was a NAM of CB1 receptor‐dependent PLCβ3 phosphorylation following THC and 2‐AG treatment. HEK 293A cells expressing CB1‐GFP2 (A–E) and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (F–J) were treated with 2‐AG or THC ± O‐2050 or CBD, and total and phosphorylated PLCβ3 levels were determined using In‐cell western. CRCs were fit using Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift (A, B, F and G) and operational model of allosterism (C, D, H and I) nonlinear regression models. E and J Schild regressions were plotted as the logarithm of 2‐AG or THC dose against the logarithm of the dose–response at EC50 – 1. N = 6.

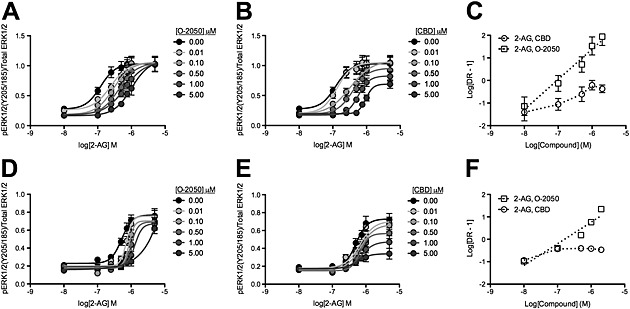

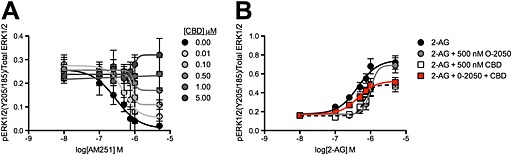

Figure 4.

CBD was a NAM of CB1 receptor‐dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation following 2‐AG treatment. HEK 293A cells expressing CB1‐GFP2 (A–C) and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (D–F) were treated with 2‐AG ± O‐2050 or CBD, and total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels were determined using In‐cell western. CRCs were fit using Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift (A and D) and operational model of allosterism (B and E) nonlinear regression models. (C and F) Schild regressions were plotted as the logarithm of 2‐AG or THC dose against the logarithm of the dose–response at EC50 – 1. N = 6.

Materials

2‐AG, CBD and O‐2050 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). THC was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (Oakville, ON, Canada). Stock solutions were made up in ethanol (THC) or DMSO (2‐AG, CBD and O‐2050, AM251) and diluted to final solvent concentrations of 0.1%.

Results

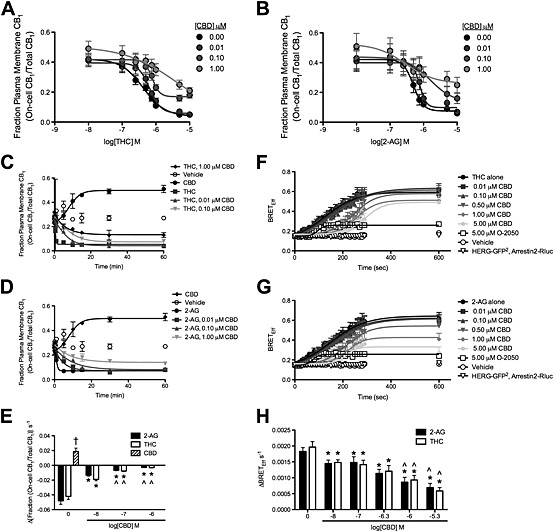

CB1 receptor internalization and kinetic experiments

We had previously observed that CBD reduced CB1 receptor internalization in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Laprairie et al., 2014a). Here, we sought to determine how CBD affected the kinetics of CB1 receptor internalization and arrestin2 recruitment in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells. The fraction of CB1 receptors at the plasma membrane was concentration‐dependently decreased by THC (Figure 1A) and 2‐AG in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Figure 1B). The efficacy and potency of THC and 2‐AG in inducing internalization of CB1 receptors were reduced by increasing concentrations of CBD (Figure 1A and B). BRET2 between arrestin2‐Rluc and CB1‐GFP2 was measured every 10 s for 4 min in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells treated with 1 μM THC (Figure 1C) or 2‐AG (Figure 1D). Increasing concentrations of CBD decreased the rate of association between arrestin2 and CB1 receptors over 4 min (Figure 1E) and decreased maximal BRETEff observed at 10 min (Figure 1C–E). The fraction of CB1 receptors at the plasma membrane was also reduced in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells treated with 1 μM THC (Figure 1F) or 2‐AG (Figure 1G) over 60 min. CBD alone increased the fraction of CB1 receptors at the membrane (Figure 1F–H). The rates of internalization and the maximum fraction internalized, for CB1 receptors, were reduced by increasing concentrations of CBD (Figure 1F–H). Similarly, Cawston et al. (2013) observed that the rate of arrestin recruitment to CB1 receptors was reduced by the allosteric modulator ORG27569. Therefore, CBD delayed the interactions between CB1 receptors and arrestin2 and increased the pool of receptors present at the plasma membrane at submicromolar concentrations, which is similar to the actions of the previously described CB1 receptor NAM, ORG27569 (Cawston et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

CBD reduced the rate and maximal BRETEff between CB1 receptors and arrestin2 and also the internalization of these receptors in THC‐treated and 2‐AG‐treated STHdh Q7/Q7 cells. (A and B) STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with THC (A) or 2‐AG (B) ± CBD for 10 min, and the fraction of CB1 receptors at the plasma membrane was quantified using On‐cell and In‐cell Western analyses. Data were fit to a nonlinear regression model with variable slope. (C–E) STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐containing and CB1‐GFP2‐containing plasmids, and BRET2 was measured every 10 s for 4 min (240 s) and again at 10 min (600 s) after treatment with THC (C) or 2‐AG (D) ± O‐2050 or CBD. Data were fit to a nonlinear regression model with variable slope. (E) The rate of arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 receptors was measured as the change in BRETEff s−1 during the first 4 min. (F–H) STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with THC (F) or 2‐AG (G) ± CBD for 60 min, and the fraction of CB1 receptors at the plasma membrane was quantified using On‐cell and In‐cell Western analyses. Data were fit to a nonlinear regression model with variable slope. (H) The rate of CB1 receptor internalization was measured as the change in the fraction On‐cell CB1/total CB1 min−1 prior to plateau. †P < 0.01 compared with 2‐AG or THC alone, *P < 0.01 compared with 0 CBD within orthosteric ligand treatment, ^P < 0.01 compared with 0.01 μM CBD (log[CBD] M = −8) within orthosteric ligand treatment; two‐way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test. N = 6.

CB1 receptor‐arrestin2 BRET2 experiments

2‐AG and THC enhance the interaction between CB1 receptors and arrestin2, as indicated by BRET2 in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Laprairie et al., 2014a). Here, we used HEK 293A cells as a heterologous expression system for CB1 receptors and arrestin2 to determine whether CBD acted as a NAM of these receptors. Treatment of HEK 293A cells with 0.01–5 μM THC or 2‐AG for 30 min produced a concentration‐dependent increase in BRETEff between arrestin2‐Rluc and CB1‐GFP2 (Figure 2A–D). The CB1 receptor antagonist O‐2050 (0.01–5.00 μM) produced a concentration‐dependent rightward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs that were best fit using the Gaddum/Schild EC50 nonlinear regression model indicative of competitive antagonism (Figure 2A and B). CBD (0.01–5 μM) treatment produced a concentration‐dependent rightward and downward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs that were best fit using the operational model of allosterism (equation (1) and Figure 2C and D). The rightward shift in EC50 was significant at 1.00 and 0.50 μM CBD for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells respectively (Table 1). The decrease in E max was significant at 0.1 and 0.5 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells respectively (Table 1). The Hill coefficient (n) was less than 1 at 0.1 and 0.5 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells respectively (Table 1). Relative RA (estimated using equation (2)) was significantly reduced at 0.01 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells (Table 1). Schild analyses of these data demonstrated that while O‐2050 behaved as a competitive antagonist, inhibition of BRETEff by CBD was nonlinear for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated HEK 293A cells (Figure 2E and Table 2). These data demonstrated that CBD behaved as a NAM of THC‐ and 2‐AG‐mediated arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 receptors in the HEK 293A heterologous expression system.

Table 1.

Effect of CBD on arrestin2 recruitment in HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells

| Agonist | CBD (μM) | EC50 μM (95% CI)a | E max (95% CI)a, b | n (95% CI)a, c | RA ± SEMd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293A | |||||

| THC | DMSO | 0.44 (0.27–0.72) | 1.22 (0.99–1.46) | 1.00 (0.89–1.06) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.75 (0.53–1.06) | 1.09 (0.90–1.29) | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) | 0.50 ± 0.05* | |

| 0.10 | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) | 0.87 (0.75–0.89)† | 0.63 (0.46–0.85)† | 0.39 ± 0.04* | |

| 0.50 | 0.71 (0.49–1.03) | 0.60 (0.41–0.80)† | 0.55 (0.43–0.69)† | 0.29 ± 0.05* | |

| 1.00 | 1.29 (0.89–1.41)† | 0.56 (0.35–0.77)† | 0.38 (0.26–0.41)† | 0.15 ± 0.03* | |

| 5.00 | 1.41 (1.04–1.77)† | 0.15 (0.09–0.31)† | 0.17 (0.08–0.24)† | 0.04 ± 0.03* | |

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.39 (0.23–0.67) | 1.13 (0.91–1.36) | 1.00 (0.86–1.13) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.52 (0.36–0.75) | 1.10 (0.92–1.28) | 0.81 (0.68–1.05) | 0.72 ± 0.04* | |

| 0.10 | 0.71 (0.59–0.86) | 0.95 (0.82–1.07) | 0.78 (0.73–0.93) | 0.46 ± 0.07* | |

| 0.50 | 0.91 (0.69–1.08)† | 0.83 (0.59–1.09)† | 0.64 (0.51–0.74)† | 0.31 ± 0.02* | |

| 1.00 | 1.00 (0.87–1.16)† | 0.71 (0.63–0.79)† | 0.33 (0.21–0.53)† | 0.24 ± 0.04* | |

| 5.00 | 1.09 (0.87–1.18)† | 0.58 (0.52–0.64)† | 0.27 (0.18–0.37)† | 0.18 ± 0.02* | |

| STHdh Q7/Q7 | |||||

| THC | DMSO | 0.34 (0.21–0.46) | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | 1.00 (0.93–1.31) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.37 (0.18–0.56) | 0.76 (0.58–0.93) | 0.87 (0.54–1.24) | 0.91 ± 0.3 | |

| 0.10 | 0.49 (0.32–0.66) | 0.74 (0.63–0.86) | 0.81 (0.43–1.07) | 0.68 ± 0.1* | |

| 0.50 | 0.72 (0.50–0.94)† | 0.70 (0.59–0.79) | 0.80 (0.35–1.06) | 0.43 ± 0.1* | |

| 1.00 | 0.80 (0.56–1.05)† | 0.54 (0.48–0.64)† | 0.74 (0.36–0.95) | 0.31 ± 0.1* | |

| 5.00 | 0.91 (0.70–1.17)† | 0.50 (0.48–0.59)† | 0.65 (0.30–0.84)† | 0.26 ± 0.0* | |

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.64 (0.56–0.73) | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) | 1.00 (0.71–1.37) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.66 (0.52–0.84) | 0.80 (0.65–0.94) | 0.89 (0.70–1.09) | 0.94 ± 0.2 | |

| 0.10 | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 0.78 (0.68–0.89) | 0.56 (0.32–0.83) | 0.72 ± 0.2* | |

| 0.50 | 1.80 (1.42–2.18)† | 0.76 (0.65–1.05) | 0.29 (0.14–0.42)† | 0.34 ± 0.1* | |

| 1.00 | 2.18 (2.06–3.53)† | 0.74 (0.68–1.04) | 0.25 (0.16–0.38)† | 0.27 ± 0.1* | |

| 5.00 | 2.20 (1.95–3.55)† | 0.44 (0.25–0.57)† | 0.25 (0.18–0.37)† | 0.16 ± 0.0* | |

CI, confidence interval.

Data shown are means ± SEM or with 95% CI, from six independent experiments.

Determined using nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters) analysis.

Maximal agonist effect BRETEff.

Hill coefficient.

Relative activity, as determined in equation (2).

Significantly different from the DMSO vehicle as determined by non‐overlapping CI.

P < 0.01, compared with DMSO vehicle; one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Table 2.

Schild analysis of arrestin2, PLCβ3 and ERK modulation by CBD

| Agonist | Slopea | R 2 | pA2 (μM) ± SEMa | IC50 (μM) (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293A | ||||

| BRET2 (arrestin2‐Rluc and CB1‐GFP2) | ||||

| THC, O‐2050 | 1.02 ± 0.11 | 0.89 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.42 (0.22–0.64) |

| THC, CBD | 0.54 ± 0.06* | 0.62 | – | 0.31 (0.19–0.37) |

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.38 ± 0.04** | 0.57 (0.29–0.67) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.54 ± 0.07* | 0.41 | – | 0.36 (0.21–0.47) |

| Gαq‐coupled phosphorylation of PLCβ3 | ||||

| THC, O‐2050 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 0.90 | 1.04 ± 0.13 | 0.45 (0.35–0.58) |

| THC, CBD | 0.59 ± 0.09* | 0.68 | – | 0.39 (0.29–0.51) |

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.29 ± 0.03** | 0.58 (0.31–0.73) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.48 ± 0.07* | 0.38 | – | 0.31 (0.17–0.46) |

| GαI/O‐coupled phosphorylation of ERK1/2 | ||||

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 0.88 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.39 (0.09–0.46) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.15 ± 0.02* | 0.62 | – | 0.26 (0.19–0.59) |

| STHdh Q7/Q7 | ||||

| BRET2 (arrestin2‐Rluc and CB1‐GFP2) | ||||

| THC, O‐2050 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.95 | 0.83 ± 0.21 | 0.35 (0.27–0.46) |

| THC, CBD | 0.34 ± 0.10* | 0.78 | – | 0.23 (0.16–0.27) |

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.35 ± 0.13** | 0.52 (0.45–0.59) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.35 ± 0.13* | 0.70 | – | 0.63 (0.57–0.89)†† |

| Phosphorylation of PLCβ3 | ||||

| THC, O‐2050 | 1.05 ± 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 0.79 (0.42–0.85) |

| THC, CBD | 0.22 ± 0.08* | 0.70 | – | 0.94 (0.62–1.19) |

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.36 ± 0.09** | 0.83 (0.46–1.17) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.29 ± 0.05* | 0.71 | – | 0.96 (0.75–1.25) |

| Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 | ||||

| 2‐AG, O‐2050 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | 0.97 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.87 (0.57–0.99) |

| 2‐AG, CBD | 0.17 ± 0.08* | 0.60 | – | 0.27 (0.18–0.36)† |

Data shown are means ± SEM or with 95% CI, from six independent experiments. CI, confidence interval.

Determined using nonlinear regression analysis with a Gaddum/Schild EC50 shift for data presented in Figures 1, 2, 3. IC50 determined at 1 μM agonist. pA2 was not determined where Schild slope was different from 1.

Significantly different from the same modulator treatment; as determined by nonoverlapping CI.

Significantly different from the same agonist treatment,

P < 0.01 compared with the same modulator treatment; one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

P < 0.01 compared with the same agonist treatment,

The NAM properties of CBD on CB1‐arrestin2 interactions were confirmed in the STHdh Q7/Q7 cell culture model of medium spiny projection neurons. As in HEK 293A cells, O‐2050 treatment produced a concentration‐dependent rightward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs that were best fit using the Gaddum/Schild EC50 nonlinear regression model indicative of competitive antagonism (Figure 2F and G), and CBD treatment produced a concentration‐dependent rightward and downward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs that were best fit using the operational model of allosterism (Figure 2H and I) in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells. The rightward shift in EC50 was significant at 0.5 μM CBD for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells (Table 1). The decrease in E max was significant at 1 and 5 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells respectively (Table 1). The Hill coefficient (n) was less than 1 at 0.5 and 5 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells respectively (Table 1). Relative RA (equation (2)) was significantly reduced at 0.1 μM for both THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated cells (Table 1). The Schild regression for these data demonstrated that O‐2050 modelled competitive antagonism for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (greater slope and R 2) (Figure 2J and Table 2). CBD alone displayed weak partial agonist activity in this assay at concentrations >2 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Taken together, these data indicate that CBD behaved as a NAM of THC‐ and 2‐AG‐mediated arrestin2 recruitment to CB1 receptors at concentrations below its reported affinity to these receptors in a cell culture model endogenously expressing CB1 receptors (Pertwee, 2008).

CB1 receptor‐mediated phosphorylation of PLCβ3

THC and 2‐AG treatment both result in a concentration‐dependent increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation in HEK 293A cells (Figure 3A–D) and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Laprairie et al., 2014a; Figure 3F–I). O‐2050 treatment resulted in a concentration‐dependent rightward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs (Figure 3A, B, F and G), while CBD treatment resulted in a rightward and downward shift in the THC and 2‐AG CRCs, in both cell lines (Figure 3C, D, H and I). O‐2050 CRCs were best fit with the Gaddum/Schild EC50 model, while CBD CRCs were best fit with the operational model of allosterism. The rightward shift in EC50 was significant at 0.5 μM CBD for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated HEK 293A cells (Table 3) and 0.5 and 1 μM CBD for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 3). The decrease in E max was significant at 1 and 0.5 μM for HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 3). The Hill coefficient (n) was less than 0.5 and 1 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated in both HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Tables 1 and 3). Relative RA was significantly reduced at 0.1 μM for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Table 3). The Schild regression for these data demonstrated that O‐2050 modelled competitive antagonism for THC‐ and 2‐AG‐treated STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, while CBD did not (greater slope and R 2) (Figure 3E and J and Table 2). As with arrestin2 recruitment, CBD alone was a weak partial agonist at concentrations >2 μM (Supporting Information Fig. S1). In the presence of 2‐AG or THC, CBD was a NAM of PLCβ3 phosphorylation in HEK 293A cells overexpressing CB1 receptors and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells endogenously expressing these receptors.

Table 3.

Effect of CBD on PLCβ3 activation in HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells

| Agonist | CBD (μM) | EC50 μM (95% CI)a | E max (95% CI)a, b | n (95% CI)a, c | RA ± SEMd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293A | |||||

| THC | DMSO | 0.47 (0.27–0.69) | 1.01 (0.82–1.20) | 1.00 (0.76–1.26) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.58 (0.34–0.81) | 0.98 (0.80–1.17) | 0.83 (0.70–1.13) | 0.79 ± 0.17 | |

| 0.10 | 0.76 (0.59–0.97) | 0.97 (0.81–1.13) | 0.73 (0.67–0.93) | 0.60 ± 0.08* | |

| 0.50 | 0.86 (0.70–1.07)† | 0.85 (0.70–1.00) | 0.54 (0.41–0.72)† | 0.46 ± 0.05* | |

| 1.00 | 1.23 (0.85–1.80)† | 0.71 (0.63–0.79)† | 0.36 (0.18–0.51)† | 0.27 ± 0.03* | |

| 5.00 | 1.26 (0.82–1.58)† | 0.51 (0.41–0.61)† | 0.16 (0.04–0.26)† | 0.19 ± 0.02* | |

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.48 (0.28–0.72) | 1.09 (0.90–1.29) | 1.00 (0.86–1.15) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.63 (0.37–0.96) | 1.11 (0.91–1.30) | 0.92 (0.81–1.02) | 0.84 ± 0.07 | |

| 0.10 | 0.83 (0.58–1.03) | 1.03 (0.74–1.32) | 0.84 (0.74–1.00) | 0.60 ± 0.07* | |

| 0.50 | 1.11 (0.95–1.35)† | 0.95 (0.80–1.10) | 0.57 (0.46–0.79)† | 0.41 ± 0.08* | |

| 1.00 | 1.62 (1.23–1.51)† | 0.78 (0.67–0.88)† | 0.22 (0.07–0.36)† | 0.23 ± 0.01* | |

| 5.00 | 2.48 (1.72–3.22)† | 0.60 (0.54–0.66)† | 0.13 (0.04–0.24)† | 0.12 ± 0.06* | |

| STHdh Q7/Q7 | |||||

| THC | DMSO | 0.58 (0.42–0.79) | 0.77 (0.65–0.89) | 1.00 (0.71–1.25) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.72 (0.61–0.85) | 0.73 (0.63–0.82) | 0.54 (0.44–0.82) | 0.77 ± 0.3 | |

| 0.10 | 0.99 (0.78–1.22) | 0.62 (0.54–0.69) | 0.51 (0.42–0.78) | 0.48 ± 0.1* | |

| 0.50 | 1.22 (0.85–1.57)† | 0.53 (0.48–0.58)† | 0.55 (0.23–0.64)† | 0.33 ± 0.1* | |

| 1.00 | 4.00 (2.76–4.32)† | 0.49 (0.37–0.52)† | 0.51 (0.17–0.62)† | 0.10 ± 0.0* | |

| 5.00 | >5.00 | – | <0.50 | 0.03 ± 0.0* | |

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.66 (0.40–0.85) | 0.73 (0.59–0.87) | 1.00 (0.70–1.18) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.67 (0.48–0.86) | 0.65 (0.56–0.74) | 0.77 (0.55–0.89) | 0.88 ± 0.2 | |

| 0.10 | 0.78 (0.58–1.01) | 0.61 (0.52–0.70) | 0.57 (0.34–0.74) | 0.71 ± 0.2* | |

| 0.50 | 0.87 (0.63–0.92) | 0.52 (0.46–0.58)† | 0.39 (0.15–0.58)† | 0.60 ± 0.1* | |

| 1.00 | 1.04 (0.87–1.61)† | 0.51 (0.43–0.56)† | 0.39 (0.12–0.50)† | 0.45 ± 0.1* | |

| 5.00 | 1.78 (1.07–2.05)† | 0.42 (0.32–0.51)† | 0.36 (0.09–0.49)† | 0.21 ± 0.0* | |

CI, confidence interval.

Data shown are means ± SEM or with 95% CI, from six independent experiments.

Determined using nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters) analysis.

Maximal agonist effect BRETEff.

Hill coefficient.

Relative activity, as determined in equation (2).

Significantly different from the DMSO vehicle as determined by non‐overlapping CI.

P < 0.01, compared with DMSO vehicle; one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

CB1 receptor‐mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2

2‐AG treatment results in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, while THC does not (Laprairie et al., 2014a). 2‐AG treatment produced a concentration‐dependent increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells (Figure 4A, B, D and E). O‐2050 treatment resulted in a concentration‐dependent rightward shift in the 2‐AG CRCs (Figure 4A and D), while CBD treatment resulted in a rightward and downward shift in the 2‐AG CRCs, in both cell lines (Figure 4B and E). O‐2050 CRCs were best fit with the Gaddum/Schild EC50 model, while CBD CRCs were best fit with the operational model of allosterism. The rightward shift in EC50 was significant at 0.5 and 1 μM CBD for HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 4). The decrease in E max was significant at 5 and 1 μM for HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 4). The Hill coefficient (n) was less than 1 at 0.01 and 0.1 μM CBD for HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 4). Relative RA was significantly reduced at 0.01 and 0.1 μM for 2‐AG‐treated HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells respectively (Table 4). The Schild regression for these data demonstrated that O‐2050 modelled competitive antagonism in HEK293A (Figure 3C) and STHdh Q7/Q7 (Figure 4F) cells, whereas CBD did not (greater slope and R 2) (Table 2). CBD was a NAM of 2‐AG‐mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation at CB1 receptors overexpressed in HEK 293A cells and endogenously expressed in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, at concentrations lower than those reported for CB1 receptor agonist activity (Mechoulam et al., 2007; McPartland et al., 2014) (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Therefore, CBD behaved as a NAM in these cell lines for arrestin2 recruitment, PLCβ3 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Table 4.

Effect of CBD on ERK activation in HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells

| Agonist | CBD (μM) | EC50 μM (95% CI)a | E max (95% CI)a, b | n (95% CI)a, c | RA ± SEMd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK 293A | |||||

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.12 (0.07–0.22) | 1.03 (0.89–1.17) | 1.00 (0.97–1.07) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.13 (0.08–0.22) | 1.05 (0.92–1.18) | 0.91 (0.82–1.03) | 0.96 ± 0.09 | |

| 0.10 | 0.33 (0.19–0.47) | 1.09 (0.90–1.28) | 0.63 (0.57–0.72)† | 0.40 ± 0.06* | |

| 0.50 | 0.39 (0.26–0.58)† | 0.96 (0.82–1.10) | 0.39 (0.29–0.58)† | 0.30 ± 0.05* | |

| 1.00 | 0.57 (0.45–0.72)† | 0.83 (0.73–0.93) | 0.27 (0.17–0.39)† | 0.17 ± 0.05* | |

| 5.00 | 0.95 (0.81–1.11)† | 0.69 (0.61–0.76)† | 0.19 (0.11–0.30)† | 0.09 ± 0.02* | |

| STHdh Q7/Q7 | |||||

| 2‐AG | DMSO | 0.50 (0.37–0.68) | 0.73 (0.63–0.83) | 1.00 (0.91–1.22) | 1.00 ± 0.0 |

| 0.01 | 0.66 (0.44–0.99) | 0.70 (0.58–0.83) | 0.78 (0.57–0.83)† | 0.74 ± 0.2* | |

| 0.10 | 0.69 (0.48–0.95) | 0.67 (0.56–0.77) | 0.79 (0.56–0.77)† | 0.67 ± 0.1* | |

| 0.50 | 0.77 (0.52–0.87) | 0.57 (0.48–0.65) | 0.73 (0.63–0.87)† | 0.56 ± 0.1* | |

| 1.00 | 0.84 (0.69–1.21)† | 0.47 (0.37–0.57† | 0.70 (0.46–0.81)† | 0.44 ± 0.1* | |

| 5.00 | 1.27 (0.81–1.47)† | 0.33 (0.26–0.41)† | 0.57 (0.27–0.72)† | 0.30 ± 0.1* | |

CI, confidence interval.

Data shown are means ± SEM or with 95% CI, from six independent experiments.

Determined using nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters) analysis.

Maximal agonist effect BRETEff.

Hill coefficient.

Relative activity, as determined in equation (2).

Significantly different from the DMSO vehicle as determined by non‐overlapping CI.

P < 0.01, compared with DMSO vehicle; one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Operational modelling of allosterism

While O‐2050 acted as a competitive orthosteric antagonist, CBD acted as a NAM in arrestin2, PLCβ3 and ERK1/2 assays. Global curve fitting of data to the operational model of allosterism was used to assess the NAM activity of CBD. Data were fit to this model by constraining E max and n (Hill slope) to 1.0 and 1.0, respectively. In this way, the allosteric co‐operativity coefficient for ligand binding (α) was found to be less than 1.0 (0.37), with no significant difference between cell lines, orthosteric ligands or assays (Table 5) indicating that CBD acted as a NAM to reduce the binding of THC and 2‐AG. CBD also reduced the efficacy of the orthosteric ligand because β (co‐operativity coefficient for ligand efficacy) was consistently less than 1 (0.44). Based on the estimated value of orthosteric ligand affinity (K A) and the ability of the orthosteric ligand to activate CB1 receptors (τA), 2‐AG (241 nM) and THC (97 nM) were able to directly activate CB1 receptors within a concentration range similar to that published earlier (see Pertwee, 2008). CBD did not display agonist activity, as shown by the estimate of τB, but exhibited a greater estimated affinity (304 nM) for CB1 receptors (K B) than would be predicted for the orthosteric site (see Pertwee, 2008). β and αβ can be used to assess ligand bias (functional selectivity) for allosteric modulators (Keov et al., 2011). No differences in β and αβ were observed in HEK 293A cells in all assays (Table 5). In STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, β and αβ were reduced in PLCβ3 assays compared with arrestin2 recruitment and ERK assays, indicating that CBD was a functionally selective inhibitor of arrestin2 and ERK1/2 pathways (Table 5). Overall, CBD was a NAM of orthosteric ligand binding and efficacy at CB1 receptors.

Table 5.

Operational model analysis of CBD at CB1 receptors in the presence of THC or 2‐AG

| BRETEff | pPLCβ3 | pERK1/2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THC | 2‐AG | THC | 2‐AG | 2‐AG | |

| Agonist modulator | CBD | CBD | CBD | CBD | CBD |

| HEK 293A | |||||

| −logα | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.47 ± 0.12 | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 0.48 ± 0.13 |

| −logβ | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.30 ± 0.07 |

| logτA a | 1.14 ± 0.26 | 1.04 ± 0.19 | 1.01 ± 0.20 | 1.12 ± 0.18 | 1.02 ± 0.12 |

| logτB b | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.10 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| K A a (nM) | 128 (56.7–159) | 262 (197–308) | 91.9 (82.2–103) | 255 (176–328) | 236 (195–275) |

| K B b (nM) | 270 (148–349) | 352 (272–409) | 268 (197–292) | 326 (279–382) | 318 (255–369) |

| αβ | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| STHdh Q7/Q7 | |||||

| −logα | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | 0.46 ± 0.18 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.13 |

| −logβ | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.12* | 0.58 ± 0.09* | 0.27 ± 0.06 |

| logτA a | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.81 ± 0.17 | 0.81 ± 0.17 | 0.79 ± 0.12 | 0.74 ± 0.18 |

| logτB b | 0.31 ± 0.11 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| K A a (nM) | 95.7 (58.6–118) | 237 (181–294) | 72.3 (59.1–107) | 255 (178–318) | 198 (137–238) |

| K B b (nM) | 278 (148.4–335) | 333 (291–376) | 259 (194–280) | 315 (281–362) | 329 (241–346) |

| αβ | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.20 |

Data shown are means ± SEM or with 95% CI, from six independent experiments. All values estimated using the operational model of allosterism described in equation (1).

logτA and K A determined for THC or 2‐AG.

logτB and K B determined for CBD.

P < 0.01 compared with BRETEff with the same agonist; one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test.

Negative allosteric modulation of antagonist binding

If CBD reduced the binding of orthosteric agonists to CB1 receptors , as predicted by the operational model of allosterism, then CBD should also reduce the binding of CB1 receptor inverse agonists and antagonists. In order to test this hypothesis, STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with the CB1 receptor inverse agonist AM251 (Pertwee, 2005), and CBD and ERK phosphorylation was measured (Figure 5A). CBD treatment resulted in a rightward and upward shift in the AM251 CRC (Figure 5A). CBD CRCs were best fit with the operational model of allosterism. To further test our hypothesis, STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with 2‐AG and 500 nM O‐2050, 500 nM CBD or 500 nM O‐2050 and 500 nM CBD (Figure 5B). Treatment of STHdh Q7/Q7 cells with 2‐AG, O‐2050 and CBD produced a CRC that was shifted right and down relative to 2‐AG alone and left relative to 2‐AG and O‐2050, indicating that CBD had reduced the competitive antagonist activity of O‐2050 and reduced the efficacy of 2‐AG (Figure 5B). Therefore, CBD was a NAM of orthosteric ligand binding as demonstrated by the reduced potency and efficacy of the CB1 receptor inverse agonist AM251 and the antagonist O‐2050.

Figure 5.

CBD was a NAM of AM251‐dependent inverse agonism and O‐2050 antagonism. STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with AM251 ± CBD (A) or 2‐AG ± O‐2050, CBD or O‐2050 and CBD (B), and total and phosphorylated ERK1/2 levels were determined using In‐cell western. CRCs were fit using the operational model of allosterism (A) or nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters) (B) models. N = 6.

Mutagenesis of the CB1 receptor

The CB1 receptor splice variants CB1A and CB1B differ in the first 89 amino acids of the N‐terminus, relative to CB1. We compared the allosteric activity of CBD in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells expressing CB1, CB1A and CB1B receptors using BRET2. BRETEff did not differ between CB1‐GFP2‐, CB1A‐GFP2‐ and CB1B‐GFP2‐expressing cells treated with 0.01–5 μM THC or 2‐AG ± 0.5 μM O‐2050 or 5 μM CBD (Supporting Information Fig. S2A and B). Therefore, the site of the negative allosteric activity of the CB1 receptor was not contained within the amino acids 1–89 that differ between CB1, CB1A and CB1B receptors but was associated with the conserved residues common to all three variants (Bagher et al., 2013; Fay and Farrens, 2013).

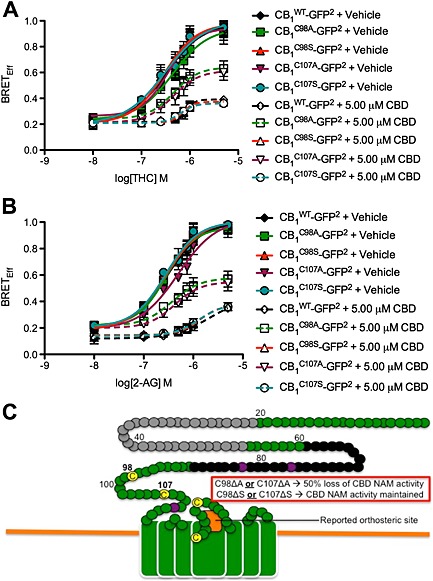

Fay and Farrens (2013) previously reported that Cys98 and Cys107 in the extracellular N‐terminus of CB1 receptors contribute to the allosteric activity of ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 by the formation of a disulfide bridge (Fay and Farrens, 2013). We hypothesized that these residues might similarly influence the allosteric activity of CBD. We wanted to determine whether it was the polarity of Cys98 and Cys107 or the formation of a disulfide bridge that contributed to allosteric activity. Each of these residues was individually mutagenized to Ala or Ser in the CB1‐GFP2 plasmid (CB1 WT‐GFP2, CB1 C98A‐GFP2, CB1 C107A‐GFP2, CB1 C98S‐GFP2 and CB1 C107S‐GFP2) and transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc into STHdh Q7/Q7 cells. Treatment of CB1 WT‐, CB1 C98A‐, CB1 C107A‐, CB1 C98S‐ or CB1 C107S‐expressing cells with 0.01–5 μM THC or 2‐AG alone resulted in a response that did not differ between CB1 receptor mutants or between THC and 2‐AG treatments (Figure 6A and B). Further, the competitive antagonist activity of 0.5 μM O‐2050 was not different in CB1 receptor mutant‐expressing cells treated with 0.01–5 μM THC or 2‐AG (Supporting Information Fig. S2C and D). Together, these data indicated that mutation of Cys98 or Cys107 did not alter the response of CB1 receptors to orthosteric ligands. Treatment of CB1 WT‐expressing cells with 0.01– μM THC or 2‐AG and 5 μM CBD resulted in a rightward and downward shift in the BRETEff CRCs (Figure 6A and B). Similarly, treatment of CB1 C98A‐expressing or CB1 C107A‐expressing cells with 0.01–5 μM THC or 2‐AG and 5.00 μM CBD resulted in a rightward and downward shift in the BRETEff CRCs compared with vehicle treatment (Table 6). The magnitude of the rightward and downward shift was less pronounced in CB1 C98A‐ and CB1 C107A‐expressing cells compared with CB1 WT‐, CB1 C98S‐ and CB1 C107S‐expressing cells treated with CBD (Table 6 and Figure 6A and B). The presence of a polar Ser or Cys at position 98 or 107 was sufficient to restore the wild‐type response to CBD. Therefore, the allosteric activity of CBD at CB1 receptors depended in part on the presence of polar residues at positions 98 and 107, independent of a disulfide bridge. Additional residues common to CB1, CB1A and CB1B receptors may also contribute to the allosteric effect of CBD (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Cys98 and Cys107 coordinate the NAM activity of CBD at CB1 receptors. (A and B) STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐ and CB1 C98A‐GFP2‐, and CB1 C98S‐GFP2‐, CB1 C107A‐GFP2‐ and CB1 C107S‐GFP2‐containing plasmids, and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with THC (A) or 2‐AG (B) ± CBD. CRCs were fit using nonlinear regression with variable slope (four parameters) N = 4. (C) Diagram of the membrane‐proximal region of CB1 receptors summarizing data presented in this figure (adapted from Fay and Farrens, 2013). Our observations and previous studies suggest that Cys98 and Cys107 contribute to CB1 receptor allosterism, while the orthosteric site is near the second extracellular loop (orange box). In this diagram, green represents extracellular surface of CB1 receptors. Black circles represent residues unique to the N‐terminus of CB1A receptors Grey circles represent residues unique to the N‐terminus of CB1B receptors. Yellow circles represent Cys. Purple circles represent N‐glycosylated residues. Residues mutated in this study are marked in bold. Non‐bold numbers indicate amino acid number relative to N‐terminus.

Table 6.

Effect of CBD on arrestin2 recruitment to mutant CB1 receptors in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells

| Agonist | Receptor | Modulator | EC50 μM (95% CI) | E max (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THC | CB1 WT | DMSO | 0.34 (0.21–0.46) | 0.96 (0.75–1.01) |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 0.91 (0.70–1.17)† | 0.30 (0.24–0.49)† | ||

| CB1 C98A | DMSO | 0.35 (0.26–0.57) | 0.94 (0.78–1.11) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 0.55 (0.37–0.67)^ | 0.64 (0.54–0.74)^, † | ||

| CB1 C107A | DMSO | 0.36 (0.23–0.46) | 0.94 (0.82–1.07) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 0.56 (0.48–0.67)^, † | 0.61 (0.54–0.73)^, † | ||

| CB1 C98S | DMSO | 0.30 (0.17–0.41) | 0.98 (0.83–1.12) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 0.97 (0.79–1.10)† | 0.37 (0.32–0.42)† | ||

| CB1 C107S | DMSO | 0.31 (0.16–0.48) | 1.00 (0.82–1.18) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 0.91 (0.80–1.02)† | 0.36 (0.31–0.41)† | ||

| 2‐AG | CB1 WT | DMSO | 0.64 (0.56–0.73) | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 2.20 (1.95–3.55)† | 0.44 (0.25–0.57)† | ||

| CB1 C98A | DMSO | 0.62 (0.54–0.78) | 0.96 (0.84–1.09) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 1.37 (1.09–1.59)^, † | 0.67 (0.59–0.71)^, † | ||

| CB1 C107A | DMSO | 0.59 (0.43–0.69) | 1.03 (0.89–1.18) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 1.42 (1.23–1.64)^, † | 0.66 (0.58–0.72)^, † | ||

| CB1 C98S | DMSO | 0.68 (0.59–0.74) | 1.01 (0.90–1.12) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 2.32 (1.97–2.57)† | 0.37 (0.24–0.50)† | ||

| CB1 C107S | DMSO | 0.67 (0.59–0.79) | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | |

| 5.00 μM CBD | 2.28 (2.14–2.40)† | 0.38 (0.24–0.52)† |

CI, confidence interval.

Data shown are means with 95% CI, from four independent experiments.

Significantly different from response to 5.00 μM CBD and DMSO vehicle in CB1 WT vehicle as determined by non‐overlapping CI.

Significantly different from DMSO vehicle within receptor group as determined by non‐overlapping CI.

Discussion and conclusions

CBD behaves as a NAM of CB1 receptors

In this study, we provide in vitro evidence for the non‐competitive negative allosteric modulation of CB1 receptors by CBD. CBD treatment resulted in negative co‐operativity (α < 1) and reduced orthosteric ligand (THC and 2‐AG) efficacy (β < 1) at concentrations lower than the predicted affinity of CBD for the orthosteric binding site at CB1 receptors [304 nM (this study) versus >4 μM (see Pertwee, 2008)]. As a NAM of CB1 receptor orthosteric ligand‐dependent effects, CBD reduced both G protein‐dependent signalling and arrestin2 recruitment, which explains both the diminished signalling and diminished BRET observed between CB1‐GFP2 and arrestin2‐Rluc. In contrast to the NAM activity of CBD and as shown previously, O‐2050 acted as a competitive orthosteric antagonist of CB1 receptors (Canals and Milligan, 2008; Higuchi et al., 2010; Hudson et al., 2010; Ferreira et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2013; Laprairie et al., 2014b) rather than a partial agonist (Wiley et al., 2011, 2012). To directly test the hypothesis that a disulfide bridge between Cys98 and Cys107 regulated the activity of CB1 receptor allosteric modulators, these residues were mutated to either Ala or Ser (Fay and Farrens, 2013). Mutation of these residues to Ala (nonpolar) decreased the NAM activity of CBD at CB1 receptors but not the activity of THC, 2‐AG, or O‐2050. The NAM activity of CBD depended upon the presence of polar (Ser or Cys) residues at positions 98 and 107 in the CB1 receptor, rather than a disulfide bridge, because replacement of either Cys residue with Ser did not change CBD NAM activity. These findings suggest that the N‐terminal, extracellular residues Cys98 and Cys107 partly regulate either the allosteric activity of CBD at CB1 receptorsdirectly or the communication between the allosteric and orthosteric sites of these receptors.

Allosteric modulators are probe‐dependent; that is, the activity of the allosteric modulator depends on the orthosteric probe being used (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002). ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 both display probe dependence because they are more potent modulators of CP55,940 binding and CP55,940‐mediated CB1 receptor activation than WIN55,212‐2 binding and WIN55,21‐2‐mediated CB1 receptor activation (Baillie et al., 2013). 2‐AG was chosen as an orthosteric probe in this study because it is the most abundant endocannabinoid in the brain, and therefore, 2‐AG would be the predominant endogenous orthosteric ligand if exogenous CBD was administered (Sugiura et al., 1999). THC and CBD are the most abundant phytocannabinoids in marijuana and are used together in varying ratios both medicinally and recreationally in marijuana (Thomas et al., 2007). Therefore, THC was selected as an alternative orthosteric probe. In HEK 293A cells, CBD did not display probe‐dependence (Table 2). In STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, CBD was a more potent NAM of CB1 receptor‐dependent arrestin2 recruitment when THC was the orthosteric probe compared with 2‐AG (Table 2). No probe‐dependence was observed for PLCβ3 and ERK1/2 signalling. BRET was used in this study to directly measure the association of CB1 receptors and arrestin2, which may be a more sensitive method for detecting probe dependence than In‐cell Western assays that measured PLCβ3 or ERK1/2.

STHdh Q7/Q7 cells express several effector proteins that CBD has been shown to modulate, including CB1, 5HT1A, GPR55, μ‐opioid receptors, PPARγ and FAAH, suggesting that CBD could have acted independently of CB1 receptors (Trettel et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2007; Laprairie et al., 2014a). However, the NAM activity of CBD was also observed in HEK 293A cells that heterologously express CB1 receptors but do not express 5HT1A, GPR55 and μ‐opioid receptors, demonstrating that these effectors did not alter the actions of CBD (Ryberg et al., 2007). HEK 293A cells do express PPARγ, but modulation of this nuclear receptor would not affect arrestin and G protein assays used over the duration of these experiments. Importantly, the NAM activity of CBD at CB1 receptors was dependent on the cannabinoid agonists 2‐AG and THC, suggesting that CBD was acting at these receptors. FAAH inhibition would have enhanced, not diminished, cannabinoid efficacy, which was not observed here. Therefore, the NAM activity of CBD at CB1 receptors documented in this study adds to the mechanisms of action through which chronic CBD mediates its effects in vivo.

No significant signalling bias was observed for CBD in HEK 293A cells because allosteric ligand efficacy (β) and co‐operativity (αβ) were not different among arrestin, PLCβ3 and ERK1/2 assays (Table 5). In STHdh Q7/Q7 cells, we observed that CBD was biased for PLCβ3 signalling compared with ERK signalling and arrestin2 recruitment as indicated by reduced β and αβ values (Table 5). Previous studies have reported that ORG27569 is also biased against ERK and arrestin signalling (Ahn et al., 2012, 2013; Baillie et al., 2013). The observation that CBD‐dependent bias was observed in STHdh Q7/Q7 cells compared with HEK 293A cells suggests that heterologous expression systems may under‐represent ligand bias (Ahn et al., 2013; Baillie et al., 2013).

CBD compared with other NAMs of CB1 receptors

Based on the functional effects of CBD on PLCβ3, ERK, arrestin2 recruitment and CB1 internalization, CBD behaved like the well‐characterized NAMs, ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 in vitro (Horswill et al., 2007; Cawston et al., 2013). At higher doses (>2 μM), CBD was able to enhance PLCβ3 and ERK phosphorylation and arrestin2 recruitment, as well as limit CB1 receptor internalization, suggesting that CBD may behave as a weak partial agonist at high concentrations, as observed elsewhere (see Mechoulam et al., 2007; McPartland et al., 2014). In this study, the primary effect of CBD at CB1 receptors was negative allosteric modulation at concentrations below 1 μM. The studies by Price et al. (2005) and Baillie et al. (2013) demonstrated that ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 paradoxically reduce orthosteric ligand efficacy and potency while increasing orthosteric ligand binding affinity and duration. It is thought that, in general, increased ligand binding results in rapid desensitization of receptors (Price et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2013). In this study, we did not directly test receptor desensitization or duration of ligand binding. We did, however, estimate ligand co‐operativity and found that CBD, unlike ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1, displayed negative co‐operativity for ligand binding (α < 1) (Price et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2013). ORG27569 and PSNCBAM‐1 increase the CB1 receptor pool at the cell surface and in doing so may potentiate CB1 receptor signalling (Cawston et al., 2013). In vivo, ORG27569 reduces food intake similar to the CB1 receptor inverse agonist rimonabant (Gamage et al., 2014). However, the in vivo actions of ORG27569 are CB1 receptor‐independent, suggesting that the in vitro pharmacology of ORG27569 does not correlate with in vivo observations (Gamage et al., 2014). Like ORG27569, CBD may mediate a subset of its in vivo actions through non‐CB1 receptor targets (Campos et al., 2012). For example, the anxiolytic and antidepressant actions of CBD may be 5HT1A receptor‐dependent, while the antipsychotic activity of CBD may be mediated by TRPV1 channels (Bisogno et al., 2001; Russo et al., 2005; Ryberg et al., 2007; Campos et al., 2012). Regardless of whether CBD has alternative targets in vivo, the work shown here demonstrates that CBD can alter the activity of common endocannabinoids and phytocannabinoids at CB1 receptors and this action is likely to be therapeutically important.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this in vitro study was the first characterization of the NAM activity of the well‐known phytocannabinoid CBD. The data presented here support the hypothesis that CBD binds to a distinct, allosteric site on CB1 receptors that is functionally distinct from the orthosteric site for 2‐AG and THC. Using an operational model of allosteric modulation to fit the data (Keov et al., 2011), we observed that CBD reduced the potency and efficacy of THC and 2‐AG at concentrations lower than the predicted affinity of CBD for the orthosteric site of CB1 receptors. Future in vivo studies should test whether the NAM activity of CBD explains the ‘antagonist of agonists’ effects reported elsewhere (Thomas et al., 2007). Indeed, the NAM activity of CBD may explain its utility as an antipsychotic, anti‐epileptic and antidepressant. In conclusion, the identification of CBD as a CB1 receptor NAM provides new insights into the compound's medicinal value and may be useful in the development of novel, CB1 receptor‐selective synthetic allosteric modulators or drug combinations.

Author contributions

R. B. L. performed the research. R. B. L., A. M. B. and E. M. D.‐W. designed the research study. M. E. M. K. and A. M. B. contributed essential reagents and tools. R. B. L. analysed the data. R. B. L., M. E. M. K.and E. M. D.‐W. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 CBD displayed weak partial agonist activity at concentrations > 2 μM. A) HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐ and CB1‐GFP2 and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with CBD. B,C) HEK 293A cell expressing CB1‐GFP2 and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with CBD and total and phosphorylated PLCβ3 (B) and ERK1/2 (C) levels were determined using In‐cell™ western. CRCs were fit using non linear regression with variable slope (4 parameter). N = 4. EC50 and E max are presented as mean (95% CI). Note theY‐axis scale is from 0.0 – 0.5.

Figure S2 The distal N‐terminus of the CB1 does not affect the activity of CBD>, and Cys98 and Cys107 do not affect the activity of orthosteric ligands at CB1 receptors. STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐ and CB1 WT‐GFP2‐, CB1A‐GFP2‐, CB1B‐GFP2‐ (A,B), CB1 C98A‐GFP2‐, and CB1 C98S‐GFP2‐, CB1 C107A‐GFP2‐, and CB1 C107S‐GFP2‐containing plasmids (C,D) and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with THC (A,C) or 2‐AG (B,D) ± O‐2050 or CBD. Concentration‐response curves were fit using non linear regression with variable slope (4 parameter). N = 4.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brian D Hudson for his critical analysis of this work. This work was supported by a partnership grant from CIHR, Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (NSHRF) and the Huntington Society of Canada (HSC) (ROP‐97185) to E. D.‐W. and a CIHR operating grant (MOP‐97768) to M. E. M. K. R. B. L. is supported by studentships from CIHR, HSC, Killam Trusts and NSHRF. A. M. B. is supported by scholarships from Dalhousie University and King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Laprairie, R. B. , Bagher, A. M. , Kelly, M. E. M. , and Denovan‐Wright, E. M. (2015) Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172: 4790–4805. doi: 10.1111/bph.13250.

References

- Ahn KH, Mahmoud MM, Kendall DA (2012). Allosteric modulator ORG27569 induces CB1 cannabinoid receptor high affinity agonist binding state, receptor internalization, and Gi protein‐independent ERK1/2 kinase activation. J Biol Chem 287: 12070–12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn KH, Mahmoud MM, Shim JY, Kendall DA (2013). Distinct roles of β‐arrestin 1 and β‐arrestin 2 in ORG27569‐induced biased signaling and internalization of the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1). J Biol Chem 288: 9790–9800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein‐Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1459–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RL, Randall MD, Chan SL (2013). The complex effects of cannabinoids on insulin secretion from rat isolated islets of Langerhans. Eur J Pharmacol 706: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagher AM, Laprairie RB, Kelly ME, Denovan‐Wright EM (2013). Co‐expression of the human cannabinoid receptor coding region splice variants (hCB1) affects the function of hCB1 receptor complexes. Eur J Pharmacol 721: 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie GL, Horswill JG, Anavi‐Goffer S, Reggio PH, Bolognini D, Abood ME et al. (2013). CB(1) receptor allosteric modulators display both agonist and signaling pathway specificity. Mol Pharmacol 83: 322–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Hanus L, De Petrocellis L, Tchilibon S, Ponde DE, Brandi I et al. (2001). Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. Br J Pharmacol 134: 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS (2012). Multiple mechanisms involved in the large‐spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367: 3364–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, Milligan G (2008). Constitutive activity of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor regulates the function of co‐expressed Mu opioid receptors. J Biol Chem 283: 11424–11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawston EE, Redmond WJ, Breen CM, Grimsey NL, Connor M, Glass M (2013). Real‐time characterization of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) allosteric modulators reveals novel mechanism of action. Br J Pharmacol 170: 893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Kenakin T (2002). G protein‐coupled receptor allosterism and complexing. Pharmacol Rev 54: 323–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay JF, Farrens DL (2013). The membrane proximal region of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 N‐terminus can allosterically modulate ligand affinity. Biochemistry 52: 8286–8294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SG, Teixeira FM, Garção P, Agostinho P, Ledent C, Cortes L et al. (2012). Presynaptic CB(1) cannabinoid receptors control frontocortical serotonin and glutamate release – species differences. Neurochem Int 61: 219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage TF, Ignatowska‐Jankowska BM, Wiley JL, Abdelrahman M, Trembleau L, Greig IR et al. (2014). In‐vivo pharmacological evaluation of the CB1‐receptor allosteric modulator Org‐27569. Behav Pharmacol 25: 182–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Hazekawa M, Sano K, Irie K, Orito K et al. (2008). Cannabidiol potentiates pharmacological effects of Delta(9)‐tetrahydrocannabinol via CB(1) receptor‐dependent mechanism. Brain Res 1188: 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Irie K, Mishima S, Araki M, Ohji M, Shirakawa A et al. (2010). The cannabinoid 1‐receptor silent antagonist O‐2050 attenuates preference for high‐fat diet and activated astrocytes in mice. J Pharmacol Sci 112: 369–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horswill JG, Bali U, Shaaban S, Keily JF, Jeevaratnam P, Babbs AJ et al. (2007). PSNCBAM‐1, a novel allosteric antagonist at cannabinoid CB1 receptors with hypophagic effects in rats. Br J Pharmacol 152: 805–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Hébert TE, Kelly ME (2010). Physical and functional interaction between CB1 cannabinoid receptors and beta2‐adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol 160: 627–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Christiansen E, Murdoch H, Jenkins L, Hansen AH, Madsen O et al. (2014). Complex pharmacology of novel allosteric free fatty acid 3 receptor ligands. Mol Pharmacol 86: 200–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James JR, Oliveira MI, Carmo AM, Iaboni A, Davis SJ (2006). A rigorous experimental framework for detecting protein oligomerization using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Nat Methods 3: 1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Tränkle C, Schlicker E (2006). Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu‐ and delta‐opioid receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 372: 354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keov P, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A (2011). Allosteric modulator of G protein‐coupled receptors: a pharmacological perspective. Neuropharmacol 60: 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprairie RB, Kelly MEM, Denovan‐Wright EM (2013). Cannabinoids increase type 1 cannabinoid receptor expression in a cell culture model of medium spiny projection neurons: implications for Huntington's disease. Neuropharmacol 72: 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprairie RB, Bagher AM, Kelly MEM, Dupré DJ, Denovan‐Wright EM (2014a). Type 1 cannabinoid receptor ligands display functional selectivity in a cell culture model of striatal medium spiny projection neurons. J Biol Chem 289: 24845–24862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprairie RB, Warford JR, Hutchings S, Robertson GS, Kelly MEM, Denovan‐Wright EM (2014b). The cytokine and endocannabinoid systems are co‐regulated by NF‐κB p65/RelA in cell culture and transgenic mouse models of Huntington's disease and in striatal tissue from Huntington's disease patients. J Neuroimmunol 267: 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Ivanova EV, Seong IS, Cashorali T, Kohane I, Gusella JF et al. (2007). Unbiased gene expression analysis implicates the huntingtin polyglutamine tract in extra‐mitochondrial energy metabolism. PLoS Genet 3: e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPartland JM, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, Pertwee R (2014). Are cannabidiol and Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br J Pharmacol 172: 737–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo‐Rodriguez E, Hanus LO (2007). Cannabidiol—recent advances. Chem Biodivers 4: 1678–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamplona FA, Ferreira J, Menezes de Lima O, Jr DFS, Bento AF, Forner S et al. (2012). Anti‐inflammatory lipoxin A4 is an endogenous allosteric enhancer of CB1 cannabinoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 21134–21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, Davenport AP, McGrath JC, Peters JA, Southan C, Spedding M, Yu W, Harmar AJ; NC‐IUPHAR. (2014) The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res 42 (Database Issue): D1098‐1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG, Ross RA, Craib SJ, Thomas A (2002). (−)‐Cannabidiol antagonizes cannabinoid receptor agonists and noradrenaline in the mouse vas deferens. Eur J Pharmacol 456: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG (2005). Inverse agonism and neutral antagonism at cannabinoind CB1 receptors. Life Sci 76: 1307–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG (2008). Ligands that target cannabinoid receptors in the brain: from THC to anandamide and beyond. Addict Biol 13: 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli F, Ligresti A, La Regina G, Coluccia A, Morera L, Allarà M et al. (2012). Indole‐2‐carboxamides as allosteric modulators of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Med Chem 55: 5627–5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MR, Baillie GL, Thomas A, Stevenson LA, Easson M, Goodwin R et al. (2005). Allosteric modulation of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol 68: 1484–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RA (2007). Allosterism and cannabinoind CB(1) receptors: the shape of things to come. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK (2005). Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5‐HT1a receptors. Neurochem Res 30: 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D, Drysdale AJ, Pertwee RG, Platt B (2007). Interactions of cannabidiol with endocannabinoid signalling in hippocampal tissue. Eur J Neurosci 25: 2093–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, Leonova J et al. (2007). The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 152: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NJ, Ward RJ, Stoddart LA, Hudson BD, Kostenis E, Ulven T et al. (2011). Extracellular loop 2 of the free fatty acid receptor 2 mediates allosterism of phenylacetamide ago‐allosteric modulator. Mol Pharmacol 80: 163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kodaka T, Nakane S, Miyashita T, Kondo S, Suhara Y et al. (1999). Evidence that the cannabinoid CB1 receptor is a 2‐arachidonoylglycerol receptor. Structure‐activity relationship of 2‐arachidonoylglycerol, ether‐linked analogues, and related compounds. J Biol Chem 274: 2794–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Baillie GL, Phillips AM, Razdan RK, Ross RA, Pertwee RG (2007). Cannabidiol displays unexpectedly high potency as an antagonist of CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists in vitro . Br J Pharmacol 150: 613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trettel F, Rigamonti D, Hilditch‐Maguire P, Wheeler VC, Sharp AH, Persichetti F et al. (2000). Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh(Q111) striatal cells. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2799–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Horswill JG, Whalley BJ, Stephens GJ (2011). Effects of the allosteric antagonist 1‐(4‐chlorophenyl)‐3‐[3‐(6‐pyrrolidin‐1‐ylpyridin‐2‐yl)phenyl]urea (PSNCBAM‐1) on CB1 receptor modulation in the cerebellum. Mol Pharmacol 79: 758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Breivogel CS, Mahadevan A, Pertwee RG, Cascio MG, Bolognini D et al. (2011). Structural and pharmacological analysis of O‐2050, a putative neutral cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol 651: 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Zhang Y, Fulp A, Maitra R, Thomas BF et al. (2012). Structural analogs of pyrazole and sulfonamide cannabinoids: effects on acute food intake in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 695: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootten D, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM (2013). Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12: 630–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 CBD displayed weak partial agonist activity at concentrations > 2 μM. A) HEK 293A and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐ and CB1‐GFP2 and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with CBD. B,C) HEK 293A cell expressing CB1‐GFP2 and STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were treated with CBD and total and phosphorylated PLCβ3 (B) and ERK1/2 (C) levels were determined using In‐cell™ western. CRCs were fit using non linear regression with variable slope (4 parameter). N = 4. EC50 and E max are presented as mean (95% CI). Note theY‐axis scale is from 0.0 – 0.5.

Figure S2 The distal N‐terminus of the CB1 does not affect the activity of CBD>, and Cys98 and Cys107 do not affect the activity of orthosteric ligands at CB1 receptors. STHdh Q7/Q7 cells were transfected with arrestin2‐Rluc‐ and CB1 WT‐GFP2‐, CB1A‐GFP2‐, CB1B‐GFP2‐ (A,B), CB1 C98A‐GFP2‐, and CB1 C98S‐GFP2‐, CB1 C107A‐GFP2‐, and CB1 C107S‐GFP2‐containing plasmids (C,D) and BRET2 was measured 30 min after treatment with THC (A,C) or 2‐AG (B,D) ± O‐2050 or CBD. Concentration‐response curves were fit using non linear regression with variable slope (4 parameter). N = 4.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item