Abstract

Background and Purpose

Aryl sulfonamide Nav1.3 or Nav1.7 voltage‐gated sodium (Nav) channel inhibitors interact with the Domain 4 voltage sensor domain (D4 VSD). During studies to better understand the structure‐activity relationship of this interaction, an additional mode of channel modulation, specifically slowing of inactivation, was revealed by addition of a single methyl moiety. The objective of the current study was to determine if these different modulatory effects are mediated by the same or distinct interactions with the channel.

Experimental Approach

Electrophysiology and site‐directed mutation were used to compare the effects of PF‐06526290 and its desmethyl analogue PF‐05661014 on Nav channel function.

Key Results

PF‐05661014 selectively inhibits Nav1.3 versus Nav1.7 currents by stabilizing inactivated channels via interaction with D4 VSD. In contrast, PF‐06526290, which differs from PF‐05661014 by a single methyl group, exhibits a dual effect. It greatly slows inactivation of Nav channels in a subtype‐independent manner. However, upon prolonged depolarization to induce inactivation, PF‐06526290 becomes a Nav subtype selective inhibitor similar to PF‐05661014. Mutation of the D4 VSD modulates inhibition of Nav1.3 or Nav1.7 by both PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290, but has no effect on the inactivation slowing produced by PF‐06526290. This finding, along with the absence of functional inhibition of PF‐06526290‐induced inactivation slowing by PF‐05661014, suggests that distinct interactions underlie the two modes of Nav channel modulation.

Conclusions and Implications

Addition of a methyl group to a Nav channel inhibitor introduces an additional mode of gating modulation, implying that a single compound can affect sodium channel function in multiple ways.

Abbreviations

- VSD

(voltage sensor domain)

- PF‐05661014

(4‐(3‐benzylureido)‐N‐(thiazol‐2‐yl) benzenesulfonamide)

- PF‐06526290

(4‐(3‐benzyl‐3‐methylureido)‐N‐(thiazol‐2‐yl) benzenesulfonamide)

- DRG

(dorsal root ganglion)

Tables of Links

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| TTX |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

Voltage‐gated sodium (Nav) channels are critical for the initiation and propagation of action potentials in electrically excitable cells (Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952; Bezanilla, 2006; Catterall, 2012). In mammals, there are nine Nav channel subtypes that can have broad or highly localized tissue expression distribution, which enables them to serve distinct physiological functions such as neuronal electrical signalling, neurotransmitter release, cardiac and skeletal muscle contraction, as well as non‐excitatory roles (Cummins et al., 2007; Catterall, 2012; Black and Waxman, 2013). The importance of Nav channels in these physiological processes is highlighted by numerous reports of human Nav genetic channelopathies associated with pain, epilepsy, autism, cardiac arrhythmias and skeletal muscle myotonias (Catterall, 2012; Eijkelkamp et al., 2012; Bennett and Woods, 2014; Krumm et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2014; Moreau et al., 2014; Waxman et al., 2014). Because of this association, pharmacological modulation of sodium channel function has been a primary mode of clinical intervention to treat many of these disorders. However, clinically used sodium channel modulators do not generally differentiate between sodium channel subtypes, which can limit their clinical utility due to CNS or cardiac Nav channel‐mediated adverse effects (England and de Groot, 2009; Wolfe and Butterworth, 2011). Therefore, there is considerable interest in developing more Nav subtype‐selective drug candidates (England and de Groot, 2009). Significant progress in this endeavour has been made with reports of selective inhibitors of Nav1.8 and more recently Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 sodium channel subtypes (Jarvis et al., 2007; Krafte et al., 2007; Kort et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2010; McCormack et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014).

Development of selective small molecule Nav channel inhibitors was recently aided by the identification and characterization of a novel pharmacological interaction region on the homologous Domain 4 voltage sensor of the channel (McCormack et al., 2013). This region is distinct from the more well‐characterized local anaesthetic binding site located within the pore of the channel (Ragsdale et al., 1994; Ragsdale et al., 1996; Fozzard et al., 2011; Panigel and Cook, 2011), which is believed to be the site of interaction for many of the clinically used non‐selective Nav channel modulators. McCormack and colleagues (2013) demonstrated that interaction with three amino acid residues on the extracellular facing S2 and S3 transmembrane segments of the Domain 4 voltage sensor was important for both activity and selectivity for both Nav1.7 and Nav1.3 selective members of an aryl sulfonamide class of Nav channel inhibitors. To better understand the structure‐activity relationships underlying this subtype selective interaction, additional aryl sulfonamide and structurally related agents have been generated and characterized (Bagal et al., 2014; Zuliani et al., 2015). During these efforts, two compounds (PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290), which differ only by a methyl moiety, have been evaluated. These studies, reported here, show that addition of a single methyl group can introduce additional modes of Nav channel modulation by this structural class.

Methods

All drug and molecular target nomenclature conforms to the BJP Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Cell line generation/isolation

Human Nav1.3, Nav1.7, Nav1.3 M123‐S1510Y/R1511W/E1559D and Nav1.7 M123‐Y1537S/W1538R/D1586E channels were stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Kv1.1/Kv1.2 (heteromultimer) channels were stably expressed in CHO cells. Methods of stable cell line generation were as described in McCormack et al. (2013). Mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons were isolated as described by Gandini et al. (2014).

Electrophysiology

Studies were performed using conventional or automated whole cell patch clamp electrophysiology. Extracellular recording solution contained 138 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 with NaOH. For DRG neuron voltage‐clamp recordings, sodium concentration was reduced to 40 mM (i.e. 98 mM choline chloride substituted for NaCl) while remaining constituents were unchanged. Internal (intracellular) recording solutions for sodium current contained 110 mM CsF, 35 mM CsCl, 5 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 with CsOH. (KF replaced CsF for potassium current recording.) Recordings were performed at room temperature using AXOPATCH 200B amplifier and pCLAMP software or PatchXpress 7000 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA). Peak current amplitudes ranging 2–10 nA were used for characterization of our compounds. Voltage errors were minimized using 80% series resistance compensation.

Compounds were made up as 10 mM DMSO stock solutions and diluted in extracellular solution to attain final concentrations desired. The final concentration of DMSO (<0.3%) had no effect on recorded current properties. Toxin stock solutions were made at 100 μM in the extracellular recording solution and stored at −20°C. Before use, stock solution was diluted in recording solution containing 0.1% of BSA. All reagents were applied to cells via a parallel pipe perfusion system (Castle et al., 2003).

For current‐clamp recordings, pipette solution contained 140 mM K‐aspartate, 10 mM KCl, 8 mM NaCl, 20 μM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM Mg‐ATP and 0.4 mM Na‐GTP pH 7.4 with KOH, and the bath solution contained 138 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 with NaOH. Action potential current threshold was determined by the first action potential elicited by a series of depolarizing current injections (30 ms) from 10 pA with 10 pA increments. Action potential frequency was determined by quantifying the number of action potentials elicited in response to 500 ms 150 pA current injections.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Clampfit 10.3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA). Statistical analysis was calculated by Student's t‐test, and P < 0.05 indicates a significant difference. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Reagents

PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290 were synthesized by the medicinal chemistry group at Neusentis, Pfizer. Scorpion α‐like toxin Lqh 3 was purchased from Latoxan, France, and tetrodotoxin (TTX) was bought from Sigma Aldrich.

Results

PF‐05661014 selectively inhibits Nav1.3 via an interaction with the D4 voltage sensor

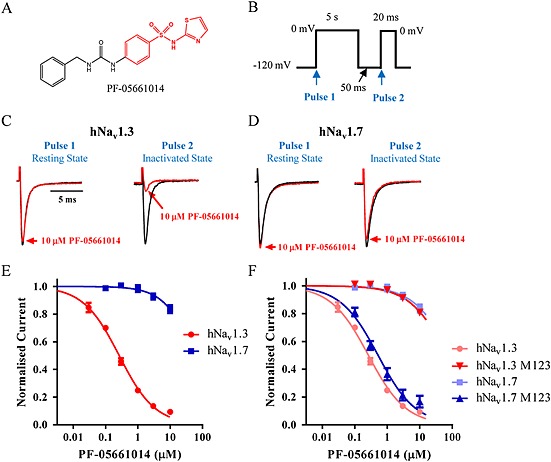

PF‐05661014 (Figure 1A) is structurally related to ICA‐121431, which was recently reported to selectively inhibit Nav1.3/Nav1.1 channels via an interaction with the Domain 4 voltage sensor domain (VSD) (McCormack et al., 2013). Utilizing the voltage protocol shown in Figure 1B, the pharmacological properties of PF‐05661014 were found to resemble those of ICA‐121431. When Nav1.3 currents were elicited by depolarizing voltage steps from −120 mV (Pulse 1), where channels are predominantly in a resting closed state, PF‐05661014 had a negligible effect on current amplitude at 10 μM (Figure 1C). In contrast, when a test pulse (Pulse 2) was preceded by a 5 s conditioning voltage step to 0 mV to drive all of the channels into the inactivated state (followed by 50 ms at −120 mV to allow non‐inhibited channels to recover from inactivation), 10 μM PF‐05661014 produced a 91 ± 2% (n = 5) reduction in current amplitude (Figure 1C and E). This finding suggests that PF‐05661014 interacts preferentially with inactivated state(s) of Nav1.3. In contrast to inhibition of Nav1.3, Figure 1D shows that 10 μM PF‐05661014 produces little or no inhibition of human Nav1.7 while in the resting or inactivated states. The concentration dependence of selective inhibition of Nav1.3 versus Nav1.7 by PF‐05661014 is illustrated in Figure 1E [IC50 for Nav1.3 0.26 ± 0.04 μM (n = 5) compared with >10 μM for human Nav1.7]. Relative potencies for inhibition of other Nav channel subtypes by PF‐05661014 are shown in Supporting Information Figure S1 and Table S1.

Figure 1.

Selective inhibition of Nav channel subtypes by PF‐05661014. (A) Structure of PF‐05661014. (B) Voltage protocol employed to evaluate PF‐05661014 activity. Cells were depolarized to 0 mV for 5 s from a holding potential of −120 mV, then repolarized to −120 mV for 50 ms to allow recovery from inactivation of unmodified channels followed by a depolarizing step to 0 mV for 20 ms to test available sodium current. Measurement of current amplitude at ‘Pulse 1’ provides a measure of resting state inhibition, whereas ‘Pulse 2’ provides a measure of inactivated state inhibition. (C) and (D) Representative current traces showing the effect of PF‐05661014 on both resting state (Pulse 1) and inactivated states (Pulse 2) of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7. Current traces have been normalized so that control traces have same relative amplitude. (E) Concentration‐dependence of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 inhibition by PF‐05661014 [IC50 0.26 ± 0.04 μM (n = 5) for Nav1.3 and >10 μM for Nav1.7 (n = 5)]. (F) Introduction of M123 (S1510Y/R1511W/E1559D) residues into Nav1.7 increases sensitivity to PF‐05661014 similar to that observed with Nav1.3 [IC50: 0.26 ± 0.04 μM (n = 5) for Nav1.3, 0.52 ± 0.17 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.7 M123]. Likewise, introduction of M123 (Y1537S/W1538R/D1586E) residues into Nav1.3 reduces its sensitivity to PF‐05661014 similar to that of Nav1.7 (IC50 > 10 μM).

Evidence that inhibition by PF‐05661014 is mediated via an interaction with the D4 voltage sensor was provided by examining the effect of previously characterized mutant forms of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 where a 3 amino acid residue motif termed M123 swapped residues found in Nav1.3 with those present in Nav1.7 (Nav1.3 M123 – S1510Y/R1511W/E1559D) or vice versa for Nav1.7 (Nav1.7 M123 – Y1537S/W1538R/D1586E) (McCormack et al., 2013) (Supporting Information Figure S2). Figure 1F shows that IC50 for inhibition of Nav1.3 M123 by PF‐05661014 is >10 μM, which is more than 40‐fold greater than Nav1.3 but similar to the IC50 for Nav1.7. In contrast, Nav1.7 M123 (IC50 0.52 ± 0.17 μM) exhibited >20‐fold increase in sensitivity to inhibition by PF‐05661014 compared with Nav1.7, being only twofold different from the IC50 for Nav1.3.

Addition of a single methyl group to PF‐05661014 produces a profound change in modulation of Nav channels

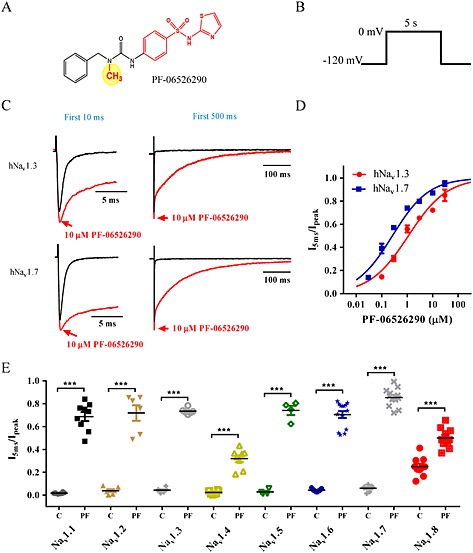

To better understand the structure‐activity relationship of D4 voltage sensor interacting Nav channel inhibitors, a close structural analogue of PF‐05661014, which has a single methyl attached to the urea linker, was evaluated. This compound, PF‐06526290 (Figure 2A), exhibited a biophysical and pharmacological profile distinct from PF‐05661014. Using the same voltage protocol used to characterize PF‐05661014, depolarization from −120 to 0 mV in the presence of 10 μM PF‐06526290 resulted in activation of Nav1.3 current that exhibited greatly slowed inactivation compared with non‐treated controls [τinact (control) = 0.82 ± 0.04 ms, n = 15 vs. τinact (PF‐06526290) = 96 ± 9 ms, n = 6]. Figure 2C shows that 10 μM PF‐06526290 produces a similar slowing of inactivation of human Nav1.7 currents. Maximal slowing of Nav1.7 inactivation with 10 μM PF‐06526290 occurred within 2 min, and more than 80% of this effect could be reversed by washout for 10 min (Supporting Information Figure S3). The concentration dependence of slowing of inactivation (Figure 2D) was determined by normalizing the current amplitude 5 ms after start of depolarizing voltage step in presence and absence of PF‐06526290 to peak sodium current amplitude. The EC50s are 1.1 ± 0.1 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.3 and 0.27 ± 0.08 μM (n = 5) for Nav1.7. Slowing of inactivation by PF‐06526290 was observed for all Nav channel subtypes evaluated, although the magnitude of effect at 10 μM was noticeably less for human Nav1.4 and Nav1.8 (Figure 2E and Supporting Information Figure S4 for sample current traces).

Figure 2.

PF‐06526290 slows Nav channel inactivation. (A) Structure of PF‐06526290 – differs from PF‐05661014 by a methyl group on the urea linker (yellow circle). (B) Protocol employed to test PF‐06526290 effect on sodium channel function. (C) Current traces for first 10 ms (left) or 500 ms (right) of the 5 s voltage step to 0 mV showing the effect of PF‐06526290 on human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 channel activity. (D) Concentration‐dependence of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 slowed inactivation following PF‐06526290 treatment. Magnitude of PF‐06526290‐induced slowing of inactivation was calculated by normalizing sodium current amplitude 5 ms after peak‐to‐peak amplitude. [EC50 0.27 ± 0.08 μM (n = 5) for Nav1.7 and 1.1 ± 0.1 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.3]. (E) Effect of 10 μM PF‐06526290 on inactivation of different human sodium channel subtypes. For each sodium channel subtype, results before (C) and after application of 10 μM PF‐06526290 (PF) are shown. Effect of PF‐06526290 was calculated as described in (D) ***P < 0.001.

PF‐06526290 produced a small hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage‐dependence of activation for both Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 and a larger depolarizing shift in voltage‐dependence of inactivation (Figure 3A and B). At submaximal concentrations of PF‐06526290, the voltage‐dependence of inactivation exhibited a double Boltzmann voltage relationship, which could be fit with two midpoint inactivation potentials and slopes equal to either control (−70 mV) or 10 μM compound (−32 mV). However, the relative proportion of the depolarized midpoint potential component (i.e. −32 mV) increased with higher PF‐06526290 concentrations (Figure 3C), suggesting that this reflects the voltage dependence of inactivation of modified channels.

Figure 3.

Effect of PF‐06526290 on voltage‐dependence of activation and inactivation of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7. (A) and (B) Voltage‐dependence of activation and inactivation of Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of 10 μM PF‐06526290. hNav1.3: activation V1/2: −12 ± 1, k: 7 ± 1.0 (n = 5); inactivation V1/2: −52 ± 1, k: 6 ± 1 (n = 5); with 10 μM PF‐06526290: activation V1/2: −19 ± 1, k: 6 ± 1 (n = 5); inactivation V1/2: −37 ± 2, k: 13 ± 2 (n = 5). hNav1.7: Activation V1/2: −20 ± 1, k: 6 ± 1 (n = 4); inactivation V1/2: −70 ± 0.6, k: 6 ± 0.5 (n = 5); with 10 μM PF‐06526290: activation V1/2: −32 ± 1, k: 6 ± 1 (n = 3); inactivation V1/2: −32 ± 1, k: 6 ± 1 (n = 6). (C) Voltage‐dependence of inactivation of Nav1.7 in the presence of 0.1, 1 and 10 μM PF‐06526290. Each data set was fitted to a double Boltzmann equation where each of the V1/2 and slope of inactivation parameters were fixed to either the control or 10 μM PF‐06526290 values shown in (B). However, the relative proportion of current with either the −70 or −32 mV V1/2 was adjusted to give best fit for each concentration of PF‐06526290 tested.

We investigated the possibility that β1 and β2 auxiliary subunits co‐expressed with Nav1.7 might modulate slowing of inactivation produced by PF‐06526290. However, no effect was observed (Supporting Information Figure S5A–C).

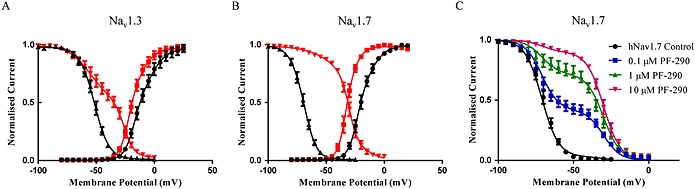

Multiple modes of modulation of Nav channels by PF‐06526290

The enhanced potency for slowing inactivation of both Nav1.7 and Nav1.3 by PF‐06526290 contrasts with the subtype‐selective inhibition of Nav1.3 versus Nav1.7 observed with its desmethyl homolog PF‐05661014 (Figure 1). Furthermore, the ability of PF‐06526290 to slow current inactivation when activated from −120 mV suggests that the compound interacts with the channel in a closed resting state, which again is different from the preferential interaction of PF‐05661014 with inactivated channels. While PF‐06526290 slows Nav channel inactivation, the process does eventually reach completion, which allows for the evaluation of compound interaction with inactivated Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 channels. Figure 4A shows that after a 5 s conditioning voltage step to 0 mV (channels are completely inactivated for >4.5 s) followed by a 50 ms rest at −120 mV to allow unmodified channels to recover from inactivation, Nav1.3 but not Nav1.7 currents elicited by the Pulse 2 voltage step to 0 mV were reduced by 10 μM PF‐06526290. The concentration‐dependence of inhibition is shown in Figure 4C with the IC50s being 5.1 ± 2.5 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.3 and >30 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.7. The dual effect of PF‐06526290 was also observed for Nav1.1, Nav1.6 and Nav1.5, but inhibition was absent or less evident for Nav1.8, Nav1.4 and Nav1.2 (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

PF‐06526290 produces subtype selective inhibition of Nav channels following prolonged depolarization. (A) Comparison of PF‐06526290 effects on Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 current traces elicited by the protocol shown in (B). Whereas slowing of inactivation by 10 μM PF‐06526290 is observed for both channel subtypes with Pulse 1, only inhibition of Nav1.3 current was observed with Pulse 2. Furthermore, neither Nav1.7 nor Nav1.3 current traces elicited by Pulse 2 exhibited the slowing of inactivation observed with Pulse 1 (for Nav1.3, the blue trace reflects the uninhibited component scaled to control). (C) Concentration‐dependence of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7 inhibition by PF‐06526290 [IC50 5 ± 2 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.3 and > 30 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.7]. (D) Inhibitory effect of PF‐06526290 on different Nav channel subtypes tested. For each sodium channel subtype, data before (C) and after application of 10 μM PF‐06526290 (PF) are shown *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

PF‐06526290 is functionally displaced from the Nav channel by slow inactivation

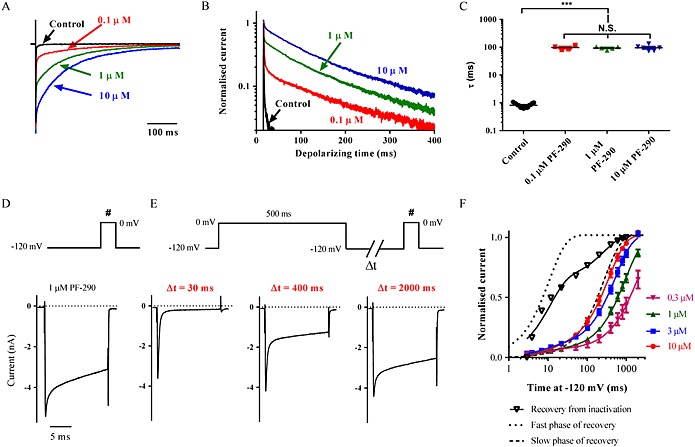

An intriguing observation is that despite the absence of inhibition of Nav1.7 by PF‐06526290, currents elicited after a 5 s depolarization to 0 mV lacked the slowed inactivation seen prior to this voltage step (Figure 4A). Although not as obvious, a similar effect was observed with Nav1.3. If the non‐inhibited component of Pulse 2 Nav1.3 current in presence of PF‐06526290 is scaled to control, little or no slowed inactivation is evident (Figure 4A scaled trace). What is the explanation for this finding? One possibility is that binding of PF‐06526290 and the process of inactivation are mutually exclusive, and the observed slowed inactivation reflects competition between the two processes. If this was the case, then the time course of modified inactivation would be expected to be dependent on PF‐06526290 concentration. Figure 5A–C shows that time course of the slow component of inactivation concentration is independent, although the proportion of current that inactivates slowly is dependent on concentration. An alternative explanation is that PF‐06526290 prevents fast inactivation to expose a slower inactivation process, and the compound has no effect on this latter process. In addition, the channel conformation associated with this slow inactivated state has a much lower affinity for PF‐06526290, so it dissociates from the channel and can only rebind when the channel returns to a resting closed state. Evidence supporting this hypothesis is shown in Figure 5D–F. Figure 5D shows slowed nactivation of Nav1.7 current induced by 1 μM PF‐06526290 following a 20 ms voltage step from −120 to 0 mV. Figure 5E shows that when a 500 ms conditioning voltage step to 0 mV to inactivate channels is applied in the presence of 1 μM PF‐06526290, followed by a 30 ms resting period at −120 mV to allow the majority of unmodified channels to recover from inactivation, currents elicited by a 20 ms voltage step to 0 mV exhibited little or no slowed inactivation. However, when the rest period at −120 mV was extended to 400 ms, ~30% of the current inactivated with slow kinetics, and when the resting period at −120 mV was further extended to 2 s, the current profile was similar to that seen in the absence of a conditioning voltage step to induce inactivation (Figure 5D and E). The rate of redevelopment of slowed inactivation increased with PF‐06526290 concentration (Figure 5F). Furthermore, the time course for the redevelopment of slowed inactivation at the highest concentration tested (10 μM) was similar to the time course of the slow component of recovery from inactivation (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Properties of PF‐06526290‐induced slowing of Nav channel inactivation. (A) Current traces of Nav1.7 in the absence and presence of 0.1, 1 and 10 μM PF‐06526290. Sodium currents were elicited by voltage steps to 0 mV for 500 ms from a holding potential of −120 mV (current amplitudes are normalized to peak for each trace). (B) Same sodium current traces from (A) normalized to peak and plotted on a log scale. (C) Time constant of inactivation (τ) in the absence and presence of 0.1, 1 and 10 μM PF‐06526290. Current decay was fit with a single exponential using Clampfit 10.3 software. There is no significant difference between the calculated time constants for slow phase of inactivation at different concentrations of PF‐06526290. ***P < 0.001 (D) Nav1.7 current trace evoked by a single pulse depolarization to 0 mV for 20 ms from a holding potential of −120 mV in presence of 1 μM PF‐06526290. (E) Current traces elicited by the voltage protocol shown in the presence of 1 μM PF‐06526290. A 500 ms depolarizing voltage step to 0 mV was applied to functionally displace PF‐06526290. A rest period at −120 mV of variable duration was applied before a 20 ms test pulse (indicated by #) to assess the fraction of the current exhibiting slowed inactivation. (F) Concentration‐dependence of time course for recovery of slowed inactivation after 500 ms voltage step to 0 mV in presence of PF‐06526290. The I 5 ms / I peak current amplitude ratios determined during the test pulse (#) are plotted versus time at −120 mV after 500 ms voltage step to 0 mV. τRecovery was determined from a least squares fit of a double exponential with the slow phase contributing 92–94% of the recovery for each concentration and τslow being 2311 ± 18, 994 ± 121, 540 ± 72 and 363 ± 63 ms for 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 μM PF‐06526290 respectively (n = 5–6). For comparison, the time course for recovery of Nav1.7 inactivation following a 500 ms voltage step to 0 mV in the absence of PF‐06526290 is also shown (Control). Data were fit with a double exponential with τfast = 11 ± 2, τslow = 270 ± 128 ms and fast/slow ratio of 0.74. The time course for fast and slow components of recovery from inactivation are illustrated by dotted and dashed curves respectively. Results shown in (D)–(F) were obtained using Molecular Devices PatchXpress automated patch clamp platform.

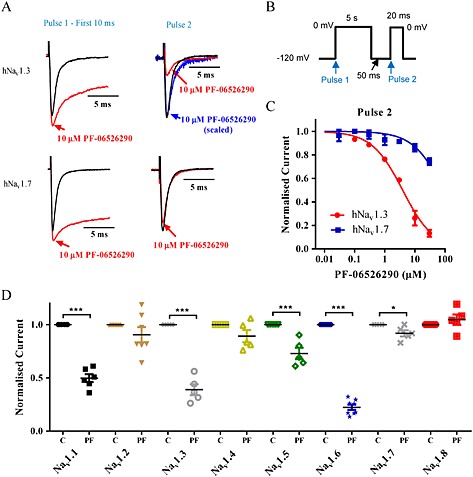

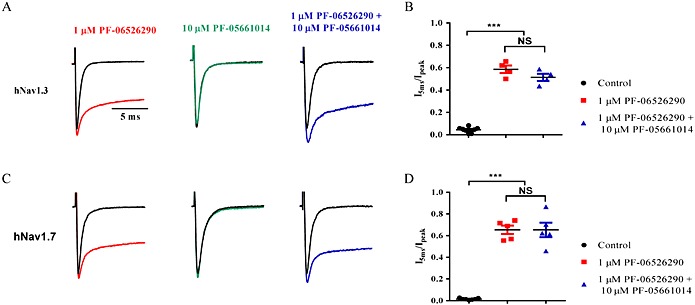

Slowing of inactivation and inhibition by PF‐06526290 result from distinct interactions with the channel

While the explanation in the previous section can account for the loss of slowed inactivation of both Nav1.7 and Nav1.3 following sustained depolarization in the presence of PF‐06526290, it does not account for the inhibition of Nav1.3, which appears to be dependent on prolonged depolarization. One possibility is that inhibition and slowing of inactivation by PF‐06526290 are mediated via functionally distinct interactions with the channel. We explored the possibility that PF‐05661014 (which only exhibits inhibition Nav1.3 without slowing inactivation) interacts with the channel in the resting state at −120 mV but is functionally silent and inhibition only manifests itself when channel conformation changes during depolarization (inactivation). If this was the case, and there is common or overlapping interaction for both inhibition and delayed inactivation, one might expect PF‐05661014 to act as an antagonist of PF‐06526290's ability to slow inactivation when applied in combination. When 10 μM PF‐05661014 was applied in combination with 1 μM PF‐06526290, there was no change in the magnitude of inactivation slowing compared with that seen with 1 μM PF‐06526290 alone (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

No functional interaction between PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290 (A) Nav1.3 current traces in the presence and absence of 1 μM PF‐06526290, or 10 μM PF‐05661014, or a mixture of 1 μM PF‐06526290 and 10 μM PF‐05661014. (B) Comparison of magnitude of slowed inactivation (determined by I 5 ms / I peak ratio) with 1 μM PF‐06526290 alone and in combination with 10 μM PF‐05661014. Effects are not statistically different. (C) and (D) Same set of experiments performed on Nav1.7 as shown in (A) and (B). Again, no difference in magnitude of inactivation slowing with 1 μM PF‐06526290 alone or in combination with 10 μM PF‐05661014 was observed.

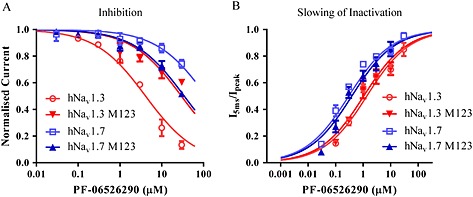

Overall, the available data suggest that distinct interactions underlie inhibition and slowed inactivation by PF‐06526290. An obvious question is whether slowed inactivation is mediated via an interaction with the Domain 4 voltage sensor similar to inhibitory action of the closely related desmethyl analogue PF‐05661014. To address this, we examined the effect of the Domain 4 VSD Nav1.3 M123 and Nav1.7 M123 mutants on both the inhibitory and inactivation slowing actions of PF‐06526290. Figure 7A compares the concentration‐dependence of PF‐06526290‐mediated inhibition of Nav1.3, Nav1.7 and the respective Nav1.3/Nav1.7 M123 Domain 4 voltage sensor mutants. The potency of inhibition of Nav1.3 M123 was decreased eightfold relative to Nav1.3, while inhibition of Nav1.7 M123 was enhanced sevenfold relative to Nav1.7. In contrast, Figure 7B shows that the mutation of Nav1.3 or Nav1.7 M123 residues has no obvious effect on the potency or magnitude of slowing of inactivation of either Nav1.3 or Nav1.7.

Figure 7.

Mutation of Domain 4 VSD M123 motif modulates inhibition but not slowing of inactivation by PF‐06526290. (A) Introduction of M123 (S1510Y/R1511W/E1559D) residues into Nav1.7 increases sensitivity to inhibition by PF‐06526290, whereas introduction of M123 (Y1537S/W1538R/D1586E) residues into Nav1.3 reduces its sensitivity to inhibition by PF‐06526209 [IC50: 5 ± 2 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.3, 30 ± 5 μM (n = 3) for Nav1.3 M123, >100 uM (n = 6) for Nav1.7 and 35 ± 4 μM (n = 3) for Nav1.7 M123]. (B) Mutation of M123 residues have no effect on PF‐06526290 induced slowing of inactivation in either Nav1.3 or Nav1.7 [EC50: 1.1 ± 0.1 μM (n = 5) for Nav1.3, 1.1 ± 0.4 μM (n = 4) for Nav1.3 M123, 0.27 ± 0.08 μM (n = 6) for Nav1.7 and 0.39 ± 0.13 μM (n = 3) for Nav1.7 M123].

Because many Nav channel modulators (Ragsdale et al., 1994; Ragsdale et al., 1996; Son et al., 2004) have been proposed to interact with or overlap the local anaesthetic binding site on D4 S6 transmembrane segment of the pore, we examined the effect of 10 µM PF‐06526290 on a Nav1.7 F1737A/Y1744A mutant, which we have previously shown to decrease local anaesthetic potency by >100‐fold (McCormack et al., 2013). No reduction in PF‐06526290‐ induced slowing of inactivation of was observed (Supporting Information Figure S6).

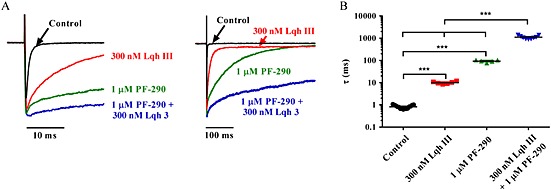

Synergistic enhancement of PF‐06526290 slowing of inactivation by site 3 scorpion toxin

To further address the site of action question, we investigated if there is an interaction between PF‐06526290 and inactivation slowing α‐scorpion toxins, which have been reported to bind to the Nav channel Domain 4 voltage sensor (Leipold et al., 2004; Gilchrist et al., 2014). Furthermore, at least one of the residues in the M123 motif important for inhibition by our small molecules is important for α‐scorpion toxin action (Leipold et al., 2004; Gilchrist et al., 2014). We compared the effect of the α‐like scorpion toxin, Lqh3, which has been reported to slow inactivation of Nav1.7 (Chen et al., 2002) alone and in combination with 1 μM PF‐06526290. Figure 8 shows that application of 300 nM Lqh3 slows Nav1.7 channel inactivation (τinact = 10 ± 1 ms compared with τinact = 0.8 ± 0.1 ms for control). However, the slowing was approximately 10‐fold less than observed with 1 μM PF‐06526290 (τinact = 96 ± 9 ms). When both 300 nM Lqh 3 and 1 μM PF‐06526290 were applied in combination, Nav1.7 inactivation was further slowed to τinact = 1100 ± 64 ms (Figure 8A and B).

Figure 8.

PF‐06526290‐mediated slowing of Nav1.7 inactivation is enhanced by site 3 targeting scorpion toxin, Lqh 3. (A) Nav1.7 current traces recorded in the presence of 300 nM Lqh 3, 1 μM PF‐06526290 (PF‐290), or a mixture of 300 nM Lqh 3 + 1 μM PF‐06526290. Currents were elicited by a 5 s voltage step from −120 to 0 mV (traces show first 20 and 500 ms). (B) Plot of inactivation time constants (τinact) in the absence and presence of 300 nM Lqh3, 1 μM PF‐06526290 (PF‐290), or a mixture of 300 nM Lqh 3 + 1 μM PF‐06526290. τinact was determined from a fit of a single exponential equation.

PF‐06526290 slows inactivation of native Nav currents and increases excitability in sensory neurons

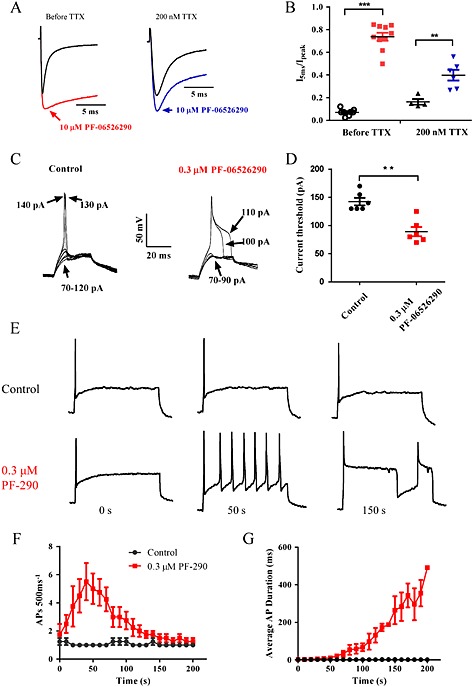

Slowing of Nav channel inactivation by scorpion and anemone toxins are associated with increased neuronal excitability (Benoit and Gordon, 2001; Yamaji et al., 2009). To determine if the PF‐06526290 produces a similar effect, we examined its actions on mouse DRG sodium currents and action potential properties. PF‐06526290 slowed inactivation of both TTX‐sensitive and resistant sodium currents in mouse DRG neurons (Figure 9A and B). PF‐06526290, 10 μM, was applied in the absence and presence of 200 nM TTX, used to isolate the TTX‐resistant component. In the absence of TTX, 10 μM PF‐06526290 slowed inactivation such that current amplitude 5 ms after start of depolarizing voltage step was 76 ± 3% of peak versus 8 ± 1% for control currents (Figure 9B). In the presence of 200 nM TTX, slowing of inactivation was less profound (I 5 ms / I peak = 42 ± 5% vs. 17 ± 3% for control) but was similar in profile and magnitude to that seen with recombinant Nav1.8 currents (Figure 2E and Supporting Information Figure S4).

Figure 9.

PF‐06526290 slows inactivation of endogenous Nav currents and increases neuronal excitability in mouse sensory neurons. (A) Sodium current traces showing the slowing of inactivation by 10 μM PF‐06526290 in the absence or presence of 200 nM TTX to isolate the TTX‐resistant component. Sodium currents were elicited by a single pulse test to 0 mV for 20 ms from a holding potential of −120 mV. (B) Plot of the I 5 ms / I peak current amplitude ratio in the presence of 10 μM PF‐06526290. (C) Effect of 0.3 μM PF‐06526290 on stimulus intensity (current injection in pA) required to initiate action potential. (D) Plot of current injection threshold for initiation of action potential in presence and absence of 0.3 μM PF‐06526290. (E) Time‐dependent change in action potential firing elicited by a 500 ms 150 pA supramaximal stimulus at 0.1 Hz in absence or following administration of 0.3 μM PF‐06526290. Plot time course of action potential frequency (F) or duration at 50% repolarization (G), in absence or following administration 0.3 μM PF‐06526290 using the same stimulus protocol as in (E).

Figure 9C–G shows the effect of PF‐06526290 on mouse DRG neuron excitability. In the presence of 0.3 μM PF‐06526290, the action potential threshold was reduced from 143 ± 7 to 89 ± 8 pA, P < 0.01 (Figure 9C and D). Using a supramaximal 500 ms stimulation of 150 pA to evoke action potential firing, 0.3 μM PF‐06526290 initially increased the frequency of action potential firing, which progressed to prolongation of action potential duration with APD50 >400 ms after 3 min of exposure (Figure 9E–G).

To test the possibility that prolongation of action potential duration by PF‐06526290 may be due in part to inhibition of potassium channels, we examined the effect of the agent on the neuronal‐delayed rectifier Kv1.1/1.2 channels. No inhibition by PF‐06526290 was observed up to 10 μM (Supporting Information Figure S7).

Discussion

The present study has focused on expanding our understanding of modulation of voltage‐gated sodium channels by a class of aryl sulfonamide agents recently reported to mediate their effects via an interaction with the voltage sensor (McCormack et al., 2013). Our findings demonstrate that addition of a single methyl group to the Nav1.3 versus Nav1.7 preferring inhibitor PF‐05661014 to form PF‐06526290 introduces an additional mode of modulation, specifically greatly slowed inactivation, which occurs with all Nav channel subtypes examined. PF‐06526290 also slows inactivation of TTX‐sensitive and resistant Nav currents in mouse sensory neurons, which is associated with action potential prolongation and increased frequency of firing similar to that observed with scorpion and anemone toxins, known to slow Nav channel inactivation (Benoit and Gordon, 2001; Abbas et al., 2013).

Consistent with the previously reported actions of the structurally related compound ICA‐121431 (McCormack et al., 2013), both PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290 were found to preferentially inhibit Nav1.3 versus Nav1.7 channels via an interaction with inactivated state(s) of the channel. Similarly, the switching of Nav1.3 to Nav1.7 selectivity via the mutation of the M123 motif suggests that this effect is mediated via an interaction with the homologous Domain 4 voltage sensor. Although the magnitude of M123 motif mutation induced modulation of the inhibitory effects of PF‐06526290 is noticeably less than PF‐05661014, this may reflect the involvement of other residues for interaction when the methyl moiety is present. McCormack et al. (2013) implicated the involvement of other residues beyond M123 motif for aryl sulfonamide Nav1.7 inhibitors. The additional Nav channel subtype independent slowed inactivation observed with PF‐06526290 appears to result from a distinct interaction because it appears to be mediated via an interaction with resting closed state(s) (and possibly open states). Although inactivation of Nav channels is slowed in the presence of PF‐06526290, prolonged depolarization (>500 ms) eventually results in inactivation, and the rate at which this is achieved is independent of concentration applied. This finding can be interpreted as PF‐06526290 interaction leads to inhibition of fast inactivation to expose a slower inactivation process that is not affected by it. Our observation that PF‐06526290 does not produce a concentration dependent shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation, rather that it increases the proportion of channels that inactivate with a more depolarized midpoint potential (−32 vs. −70 mV for unmodified channels), is consistent with this hypothesis. We also found that the establishment of slowed inactivation results in the functional displacement of PF‐06526290 from the channel despite its continued presence and re‐interaction only occurs after the channels return to the resting closed state.

While the functional displacement of PF‐06526290 was most evident with Nav1.7 (due to the absence of an inhibitory effect), it was also observed with the non‐inhibited component of Nav1.3, suggesting that resting state dependent slowing of inactivation and inactivated state dependent inhibition are functionally distinct processes. Further evidence for this comes from the finding that PF‐05661014, which only exhibits inhibitor effects, had no effect on the ability of PF‐06526290 to slow inactivation when administered in combination. This suggests that there is no ‘silent’ non‐functional mutual exclusivity between the two agents with resting closed channels. Finally, while the inhibitory actions of PF‐06526290 and PF‐05661014 are modulated by M123 motif mutation of Domain 4 VSD, these mutations had no effect on slowing of inactivation of either Nav1.3 or Nav1.7 by PF‐06526290. It can be noted that the absence of effect of M123 motif mutation on PF‐06526290 induced slowing of inactivation does not exclude the possibility that this effect is still mediated via an interaction with the Domain 4 VSD, because the mutations swapped Nav1.3 for Nav1.7 residues or vice versa, and both channel subtypes exhibit a similar slowed inactivation in the presence of this modulator.

Homologous Domain 4 VSD has been shown to be the site of interaction for scorpion and anemone peptide toxins, which, like PF‐06526290, cause slowing of inactivation of Nav channels (Rogers et al., 1996; Leipold et al., 2004; Billen et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011; Gilchrist et al., 2014; Martin‐Eauclaire et al., 2015). Interestingly, site 3 scorpion α and anemone toxins achieve their modulation of inactivation via an interaction with amino acid residues that include the third residue of the M123 motif (E1559 on Nav1.3 and D1586 on Nav1.7) (Rogers et al., 1996; Leipold et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2011; Gurevitz, 2012; Gilchrist et al., 2014). Given the similar mode of channel modulation and preference for resting state channels, as well as the overlap of D4 VSD regions important for toxin action and the inhibitory effects of PF‐06526290, we explored possible interaction of the α‐like toxin Lqh3 with PF‐06526290. If the two agents interact with a common site, we would expect that the time course of slowing of inactivation when the Lqh3 and PF‐06526290 are applied together would be somewhere between the time courses observed with each agent applied individually. In contrast to this expectation, inactivation was slowed a further 10‐fold, suggesting synergism between Lqh3 and PF‐06526290. This implies that Lqh3 and PF‐06526290 have functionally coupled but distinct interactions with the channel. However, as with the M123 mutations, these findings do not exclude the possibility that the slowed inactivation still results from an interaction with the D4 VSD.

We did explore the possibility that PF‐06526290 might interact with the local anaesthetic binding site within the pore because a number of Nav channel activators like veratridine are reported to interact with or near this region of the channel (Son et al., 2004; Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2005; Yoshinaka‐Niitsu et al., 2012). However, we found that mutation of the local anaesthetic binding site on Nav1.7 site did not prevent PF‐06526290 mediated slowing of inactivation, suggesting that this region is probably not involved in the interaction producing this effect.

So, at this time, the region of the sodium channel responsible for PF‐06526290 induced slowing of inactivation remains elusive. We have not been able to exclude the possibility that the effect is mediated via an interaction with the Domain 4 VSD, so future studies directed towards investigating the potential role of other residues in the region may help in this regard. Of course, there remains the possibility that the site of interaction mediating the slowed inactivation is located elsewhere, including other VSDs. We have shown that the magnitude of slowing of inactivation of Nav1.4 and Nav1.8 is considerably less than that observed with the other Nav subtypes. It may be possible to exploit these differences in future studies to construct homologous domain swap chimeras to home in on potential regions of interaction in a manner similar to that successfully employed to identify the D4 VSD interaction site for selective inhibitors (McCormack et al., 2013). Potential guidance can also come from examining previously characterized agents where small structural changes have also been reported to change modulatory effect. For example, the dual inhibition and slowing of voltage‐dependent sodium channel inactivation has also been reported for the cardiac inotropic agent DPI 201–106 (Romey et al., 1987; Wang et al., 1990). The (S)‐enantiomer of DPI 201–106 slows inactivation, whereas the (R)‐enantiomer inhibits Nav channel function. The exact location on the channel mediating these effects remains to be reported, although a detailed study by Wang et al. (1990) did provide evidence that slowing of inactivation and inhibition were mediated by separate non‐overlapping interactions with the channel. The enantiomer dependent effects of DPI 201–106 are reminiscent of the voltage dependent calcium channel inhibition/activation elicited by enantiomers of dihydropyridines (Hockerman et al., 1997; Natale and Steiger, 2014), which have been reported to result from interactions with the homologous domains 3 and 4 S5 and S6 transmembrane helices that form the pore (Peterson et al., 1996; Hockerman et al., 1997; Schleifer, 1999). Similar inhibition/activation switching has been reported for modulators of the Trp channel TRPA1 and potassium channels as well as agonist/inverse agonists of GABA receptor channels (Ferretti et al., 2004; Defalco et al., 2010; Banzawa et al., 2014). Interestingly, a recent study has reported that addition of a single methyl group to the non‐selective Kv7.2‐7.5 opener (S)‐2 converts it to a subtype selective inhibitor/opener (Blom et al., 2014).

Conclusions

In summary, the current study has demonstrated that addition of a single methyl group can introduce additional modes of Nav channel modulation by a class of agents that have previously been shown to mediate at least one of their effects via an interaction with the voltage sensor. The ability of PF‐06526290 to interact with distinct gating states to elicit opposing effects on conduction may make it a useful tool for further understanding how pharmacological modulation of gating leads to conduction changes.

Author contributions

L. W., S. G. Z. and D. M. P. performed the research. L. W. and N. A. C. designed the research. L. W. and N. A. C. analysed the data. L. W. and N. A. C. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Lingxin Wang, Shannon G. Zellmer, David M. Printzenhoff and Neil A. Castle were employees of Pfizer, which is the developer of PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290.

Supporting information

Figure S1 PF‐05661014 inhibition of human voltage dependent sodium (Nav) channels exhibits subtype selectivity. Plot shows concentration dependent inhibition of various human Nav channel subtypes by PF‐05661014. Same double‐pulse recording protocol as introduced in Fig. 1 was used to determine inhibition. Concentration response curves were fitted with a Logistic Equation to derive estimated IC50s (Table S1). Values are means ± SEM, number of experiments were shown as n in Table S1.

Figure S2 Comparison of amino acid residues making up Domain 4 voltage sensor of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7. Residues labelled M1, 2 and 3, reported to be important for interaction of aryl sulfonamide inhibitors (McCormack et al 2013) are shown. For Nav1.3, M1 is S1510, M2 is R1511, and M3 is E1559 and for Nav1.7, M1 is Y1537, M2 is W1538, and M3 is D1586.

Figure S3 Time course of 10 μM PF‐06526290 slowing of inactivation and washout. Sodium currents at 5 ms time point were normalised to the I5ms when the effect of PF‐06526290 on slowing of inactivation was stabilised.

Figure S4 PF‐06526290 mediated slowing of inactivation of different human Nav channel subtypes. Sodium currents were elicited by voltage steps to 0 mV from a holding potential of −120 mV (current amplitudes are normalized to peak for each trace).

Figure S5 Sodium channel auxiliary subunits β1 and β2 have no effects on PF‐06526290 (PF‐290) induced slowing of inactivation or inhibition. (Black: control; Red: 10 μM PF‐06526290) (A) Representative current traces of Nav1.7 or Nav1.7 + β1/β2 with and without 10 μM PF‐290 induced by a two‐pulse test protocol as shown in Figure 1. (B) Co‐expressing of β1/β2 with Nav1.7 had no effect on PF‐290 induced slowing of inactivation (I5ms/Ipeak). (C) Coexpressing of β1/β2 with Nav1.7 did not alter the effect of PF‐290 on inhibition of sodium current.

Figure S6 Current traces comparing effect of 10 μM PF‐06526290 on inactivation of Nav1.7 versus the local anesthetic binding site mutant Nav1.7 F1737A/Y1744A. Left is a plot of data (I5ms/Ipeak current amplitude ratio) obtained from 6‐9 separate experiments.

Figure S7 PF‐06526290 (PF‐290) has no effect on Kv1.1/1.2 channels (heteromultimer) stably expressed in CHO cells. (A) Representative current traces induced by single pulse test to +40 mV for 1s, followed by repolarising to ‐50 mV for 1s before and after 10 min continuous application of 10 μM PF‐06526290. (B) Effects of 10 μM PF‐06526290 on peak potassium currents at different voltages (n=3).

Table S1 PF‐05661014 inhibition of human voltage dependent sodium channel subtypes.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

All of the studies described in this article were performed by the authors while employees of the Neuroscience and Pain Research Unit of Pfizer. L. W. is a recipient of a Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development postdoctoral fellowship. The authors would like to thank Sally Stoehr and Peter Miu for help with initial experiments, Christopher West and Wes Ergle for synthesizing PF‐05661014 and PF‐06526290, Sonia Santos for constructing M123 mutants, Eva Prazak and Doug McIlvaine for providing cells and Mark Chapman and Doug Krafte for their suggestions during the drafting of the manuscript.

Wang, L. , Zellmer, S. G. , Printzenhoff, D. M. , and Castle, N. A. (2015) Addition of a single methyl group to a small molecule sodium channel inhibitor introduces a new mode of gating modulation. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172: 4905–4918. doi: 10.1111/bph.13259.

References

- Abbas N, Gaudioso‐Tyzra C, Bonnet C, Gabriac M, Amsalem M, Lonigro A et al. (2013). The scorpion toxin Amm VIII induces pain hypersensitivity through gain‐of‐function of TTX‐sensitive Na(+) channels. Pain 154 (8): 1204–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA et al. (2013). The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1607–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagal SK, Chapman ML, Marron BE, Prime R, Storer RI, Swain NA (2014). Recent progress in sodium channel modulators for pain. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 24 (16): 3690–3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banzawa N, Saito S, Imagawa T, Kashio M, Takahashi K, Tominaga M et al. (2014). Molecular basis determining inhibition/activation of nociceptive receptor TRPA1 protein: a single amino acid dictates species‐specific actions of the most potent mammalian TRPA1 antagonist. J Biol Chem 289 (46): 31927–31939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DL, Woods CG (2014). Painful and painless channelopathies. Lancet Neurol 13 (6): 587–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit E, Gordon D (2001). The scorpion alpha‐like toxin Lqh III specifically alters sodium channel inactivation in frog myelinated axons. Neuroscience 104 (2): 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F (2006). The action potential: from voltage‐gated conductances to molecular structures. Biol Res 39 (3): 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billen B, Bosmans F, Tytgat J (2008). Animal peptides targeting voltage‐activated sodium channels. Curr Pharm Des 14 (24): 2492–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JA, Waxman SG (2013). Noncanonical roles of voltage‐gated sodium channels. Neuron 80 (2): 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom SM, Rottlander M, Kehler J, Bundgaard C, Schmitt N, Jensen HS (2014). From pan‐reactive KV7 channel opener to subtype selective opener/inhibitor by addition of a methyl group. PLoS One 9: e100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NA, Wickenden AD, Zou A (2003). Electrophysiological analysis of heterologously expressed Kv and SK/IK potassium channels. Current protocols in pharmacology / editorial board, SJ Enna (editor‐in‐chief) … [et al.] Chapter 11: Unit11.15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Catterall WA (2012). Voltage‐gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol 590 (Pt 11): 2577–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lu S, Leipold E, Gordon D, Hansel A, Heinemann SH (2002). Differential sensitivity of sodium channels from the central and peripheral nervous system to the scorpion toxins Lqh‐2 and Lqh‐3. Eur J Neurosci 16 (4): 767–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Sheets PL, Waxman SG (2007). The roles of sodium channels in nociception: implications for mechanisms of pain. Pain 131 (3): 243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defalco J, Steiger D, Gustafson A, Emerling DE, Kelly MG, Duncton MA (2010). Oxime derivatives related to AP18: agonists and antagonists of the TRPA1 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20 (1): 276–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkelkamp N, Linley JE, Baker MD, Minett MS, Cregg R, Werdehausen R et al. (2012). Neurological perspectives on voltage‐gated sodium channels. Brain: J Neurol 135 (Pt 9): 2585–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England S, de Groot MJ (2009). Subtype‐selective targeting of voltage‐gated sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol 158 (6): 1413–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti V, Gilli P, Borea PA (2004). Structural features controlling the binding of beta‐carbolines to the benzodiazepine receptor. Acta Crystallogr SecB, Struct Sci 60 (Pt 4): 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozzard HA, Sheets MF, Hanck DA (2011). The sodium channel as a target for local anesthetic drugs. Front Pharmacol 2: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini MA, Sandoval A, Felix R (2014). Whole‐cell patch‐clamp recordings of Ca2+ currents from isolated neonatal mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2014 (4): 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist J, Olivera BM, Bosmans F (2014). Animal toxins influence voltage‐gated sodium channel function. Handb Exp Pharmacol 221: 203–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevitz M (2012). Mapping of scorpion toxin receptor sites at voltage‐gated sodium channels. Toxicon 60 (4): 502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockerman GH, Peterson BZ, Sharp E, Tanada TN, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1997). Construction of a high‐affinity receptor site for dihydropyridine agonists and antagonists by single amino acid substitutions in a non‐L‐type Ca2+ channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 (26): 14906–14911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol 117 (4): 500–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Honore P, Shieh CC, Chapman M, Joshi S, Zhang XF et al. (2007). A‐803467, a potent and selective Nav1.8 sodium channel blocker, attenuates neuropathic and inflammatory pain in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 (20): 8520–8525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kort ME, Drizin I, Gregg RJ, Scanio MJ, Shi L, Gross MF et al. (2008). Discovery and biological evaluation of 5‐aryl‐2‐furfuramides, potent and selective blockers of the Nav1.8 sodium channel with efficacy in models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain. J Med Chem 51 (3): 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafte DS, Chapman M, Marron B, Atkinson R, Liu Y, Ye F et al. (2007). Block of Nav1.8 by small molecules. Channels (Austin) 1 (3): 152–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N, O'Roak BJ, Shendure J, Eichler EE (2014). A de novo convergence of autism genetics and molecular neuroscience. Trends Neurosci 37 (2): 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Park CK, Chen G, Han Q, Xie RG, Liu T et al. (2014). A monoclonal antibody that targets a NaV1.7 channel voltage sensor for pain and itch relief. Cell 157 (6): 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Leipold E, Lu S, Gordon D, Hansel A, Heinemann SH (2004). Combinatorial interaction of scorpion toxins Lqh‐2, Lqh‐3, and LqhalphaIT with sodium channel receptor sites‐3. Mol Pharmacol 65 (3): 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Eauclaire MF, Ferracci G, Bosmans F, Bougis PE (2015). A surface plasmon resonance approach to monitor toxin interactions with an isolated voltage‐gated sodium channel paddle motif. J Gen Physiol 145 (2): 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack K, Santos S, Chapman ML, Krafte DS, Marron BE, West CW et al. (2013). Voltage sensor interaction site for selective small molecule inhibitors of voltage‐gated sodium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (29): E2724–2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Wang L, Zhong J (2014). Sodium channels, cardiac arrhythmia, and therapeutic strategy. Adv Pharmacol 70: 367–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau A, Gosselin‐Badaroudine P, Chahine M (2014). Biophysics, pathophysiology, and pharmacology of ion channel gating pores. Front Pharmacol 5: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale NR, Steiger SA (2014). 4‐Isoxazolyl‐1,4‐dihydropyridines: a tale of two scaffolds. Future Med Chem 6 (8): 923–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigel J, Cook SP (2011). A point mutation at F1737 of the human Nav1.7 sodium channel decreases inhibition by local anesthetics. J Neurogenet 25 (4): 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (Database Issue): D1098–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, Tanada TN, Catterall WA (1996). Molecular determinants of high affinity dihydropyridine binding in L‐type calcium channels. J Biol Chem 271 (10): 5293–5296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1994). Molecular determinants of state‐dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science 265 (5179): 1724–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1996). Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage‐gated Na+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93 (17): 9270–9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JC, Qu Y, Tanada TN, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1996). Molecular determinants of high affinity binding of alpha‐scorpion toxin and sea anemone toxin in the S3‐S4 extracellular loop in domain IV of the Na+ channel alpha subunit. J Biol Chem 271 (27): 15950–15962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romey G, Quast U, Pauron D, Frelin C, Renaud JF, Lazdunski M (1987). Na+ channels as sites of action of the cardioactive agent DPI 201–106 with agonist and antagonist enantiomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 (3): 896–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer KJ (1999). Stereoselective characterization of the 1,4‐dihydropyridine binding site at L‐type calcium channels in the resting state and the opened/inactivated state. J Med Chem 42 (12): 2204–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son SL, Wong K, Strichartz G (2004). Antagonism by local anesthetics of sodium channel activators in the presence of scorpion toxins: two mechanisms for competitive inhibition. Cell Mol Neurobiol 24 (4): 565–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Jia Q, Zenova AY, Chafeev M, Zhang Z, Lin S et al. (2014). The discovery of benzenesulfonamide‐based potent and selective inhibitors of voltage‐gated sodium channel Na(v)1.7. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 24 (18): 4397–4401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS (2005). Sodium channel activators: model of binding inside the pore and a possible mechanism of action. FEBS Lett 579 (20): 4207–4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Dugas M, Ben Armah I, Honerjager P (1990). Interaction between DPI 201–106 enantiomers at the cardiac sodium channel. Mol Pharmacol 37 (1): 17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yarov‐Yarovoy V, Kahn R, Gordon D, Gurevitz M, Scheuer T et al. (2011). Mapping the receptor site for alpha‐scorpion toxins on a Na+ channel voltage sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 (37): 15426–15431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG, Merkies IS, Gerrits MM, Dib‐Hajj SD, Lauria G, Cox JJ et al. (2014). Sodium channel genes in pain‐related disorders: phenotype‐genotype associations and recommendations for clinical use. Lancet Neurol 13 (11): 1152–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JW, Butterworth JF (2011). Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: update on mechanisms and treatment. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 24 (5): 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Little MJ, Nishio H, Billen B, Villegas E, Nishiuchi Y et al. (2009). Synthesis, solution structure, and phylum selectivity of a spider delta‐toxin that slows inactivation of specific voltage‐gated sodium channel subtypes. J Biol Chem 284 (36): 24568–24582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Xiao Y, Kang D, Liu J, Li Y, Undheim EA et al. (2013). Discovery of a selective NaV1.7 inhibitor from centipede venom with analgesic efficacy exceeding morphine in rodent pain models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (43): 17534–17539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaka‐Niitsu A, Yamagaki T, Harada M, Tachibana K (2012). Solution NMR analysis of the binding mechanism of DIVS6 model peptides of voltage‐gated sodium channels and the lipid soluble alkaloid veratridine. Bioorg Med Chem 20 (9): 2796–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XF, Shieh CC, Chapman ML, Matulenko MA, Hakeem AH, Atkinson RN et al. (2010). A‐887826 is a structurally novel, potent and voltage‐dependent Na(v)1.8 sodium channel blocker that attenuates neuropathic tactile allodynia in rats. Neuropharmacology 59 (3): 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani V, Rapalli A, Patel MK, Rivara M (2015). Sodium channel blockers: a patent review (2010–2014). Expert Opin Ther Pat 25 (3): 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 PF‐05661014 inhibition of human voltage dependent sodium (Nav) channels exhibits subtype selectivity. Plot shows concentration dependent inhibition of various human Nav channel subtypes by PF‐05661014. Same double‐pulse recording protocol as introduced in Fig. 1 was used to determine inhibition. Concentration response curves were fitted with a Logistic Equation to derive estimated IC50s (Table S1). Values are means ± SEM, number of experiments were shown as n in Table S1.

Figure S2 Comparison of amino acid residues making up Domain 4 voltage sensor of human Nav1.3 and Nav1.7. Residues labelled M1, 2 and 3, reported to be important for interaction of aryl sulfonamide inhibitors (McCormack et al 2013) are shown. For Nav1.3, M1 is S1510, M2 is R1511, and M3 is E1559 and for Nav1.7, M1 is Y1537, M2 is W1538, and M3 is D1586.

Figure S3 Time course of 10 μM PF‐06526290 slowing of inactivation and washout. Sodium currents at 5 ms time point were normalised to the I5ms when the effect of PF‐06526290 on slowing of inactivation was stabilised.

Figure S4 PF‐06526290 mediated slowing of inactivation of different human Nav channel subtypes. Sodium currents were elicited by voltage steps to 0 mV from a holding potential of −120 mV (current amplitudes are normalized to peak for each trace).

Figure S5 Sodium channel auxiliary subunits β1 and β2 have no effects on PF‐06526290 (PF‐290) induced slowing of inactivation or inhibition. (Black: control; Red: 10 μM PF‐06526290) (A) Representative current traces of Nav1.7 or Nav1.7 + β1/β2 with and without 10 μM PF‐290 induced by a two‐pulse test protocol as shown in Figure 1. (B) Co‐expressing of β1/β2 with Nav1.7 had no effect on PF‐290 induced slowing of inactivation (I5ms/Ipeak). (C) Coexpressing of β1/β2 with Nav1.7 did not alter the effect of PF‐290 on inhibition of sodium current.

Figure S6 Current traces comparing effect of 10 μM PF‐06526290 on inactivation of Nav1.7 versus the local anesthetic binding site mutant Nav1.7 F1737A/Y1744A. Left is a plot of data (I5ms/Ipeak current amplitude ratio) obtained from 6‐9 separate experiments.

Figure S7 PF‐06526290 (PF‐290) has no effect on Kv1.1/1.2 channels (heteromultimer) stably expressed in CHO cells. (A) Representative current traces induced by single pulse test to +40 mV for 1s, followed by repolarising to ‐50 mV for 1s before and after 10 min continuous application of 10 μM PF‐06526290. (B) Effects of 10 μM PF‐06526290 on peak potassium currents at different voltages (n=3).

Table S1 PF‐05661014 inhibition of human voltage dependent sodium channel subtypes.

Supporting info item