Abstract

Purpose

Observational studies have demonstrated increased colon cancer recurrence in states of relative hyperinsulinemia, including sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and increased dietary glycemic load. Greater coffee consumption has been associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes and increased insulin sensitivity. The effect of coffee on colon cancer recurrence and survival is unknown.

Patients and Methods

During and 6 months after adjuvant chemotherapy, 953 patients with stage III colon cancer prospectively reported dietary intake of caffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and nonherbal tea, as well as 128 other items. We examined the influence of coffee, nonherbal tea, and caffeine on cancer recurrence and mortality using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

Patients consuming 4 cups/d or more of total coffee experienced an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for colon cancer recurrence or mortality of 0.58 (95% CI, 0.34 to 0.99), compared with never drinkers (Ptrend = .002). Patients consuming 4 cups/d or more of caffeinated coffee experienced significantly reduced cancer recurrence or mortality risk compared with abstainers (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.91; Ptrend = .002), and increasing caffeine intake also conferred a significant reduction in cancer recurrence or mortality (HR, 0.66 across extreme quintiles; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.93; Ptrend = .006). Nonherbal tea and decaffeinated coffee were not associated with patient outcome. The association of total coffee intake with improved outcomes seemed consistent across other predictors of cancer recurrence and mortality.

Conclusion

Higher coffee intake may be associated with significantly reduced cancer recurrence and death in patients with stage III colon cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Mounting evidence supports an association between excess energy balance and increased risk of developing colon cancer.1–4 Promotion of cancer by hyperinsulinemia has been proposed as the mechanism underlying this relationship,5,6 and prospective studies find a significant association between a history of type 2 diabetes (T2D), elevated plasma insulin, and C-peptide, and subsequent colorectal cancer risk.6–11 Beyond cancer risk, observational studies of patients with established colorectal cancer suggest that energy excess, as manifested by T2D, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, Western pattern diet, high dietary glycemic load, and high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, confers an increased risk of colon cancer recurrence and mortality.12–17 Moreover, increased cancer mortality was observed among patients with stage I, II, and III colorectal cancer with elevated plasma C-peptide or low insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1.15

Insight into the role of other dietary factors may contribute to strategies to improve outcome in patients with colon cancer. Coffee is commonly consumed worldwide, and coffee consumption has been associated with decreased risk of T2D,18–22 lower plasma C-peptide,11,23 and increased plasma adiponectin, an endogenous insulin sensitizer.24,25 In addition, some, but not all, studies demonstrate an inverse relationship between coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer.26–28

In light of evidence supporting a link between excess energy balance, hyperinsulinemia, and increased recurrence in patients with colon cancer, we prospectively examined the association of coffee intake with cancer recurrence and mortality in a cohort of patients with stage III colon cancer enrolled onto a National Cancer Institute–sponsored randomized clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy. In this trial, comprehensive data on diet and lifestyle were collected before any documentation of cancer recurrence. Moreover, because data on pathologic stage, performance status, postoperative treatment, and follow-up were carefully captured in this trial, the simultaneous effects of disease characteristics and adjuvant therapy use could be assessed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

Patients in this prospective cohort participated in the National Cancer Institute–sponsored Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803 (CALGB 89803; now Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology) adjuvant therapy trial for stage III colon cancer, comparing therapy with once per week fluorouracil and leucovorin with therapy with once per week irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT000038350).29 Between 1999 and 2001, 1,264 patients were enrolled. After 87 patients were enrolled, an amendment required patients to complete a self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that captured diet and lifestyle habits midway through adjuvant therapy (4 months after surgery; questionnaire 1 [Q1]), and again, 6 months after completion of treatment (14 months after surgery; questionnaire 2 [Q2]).

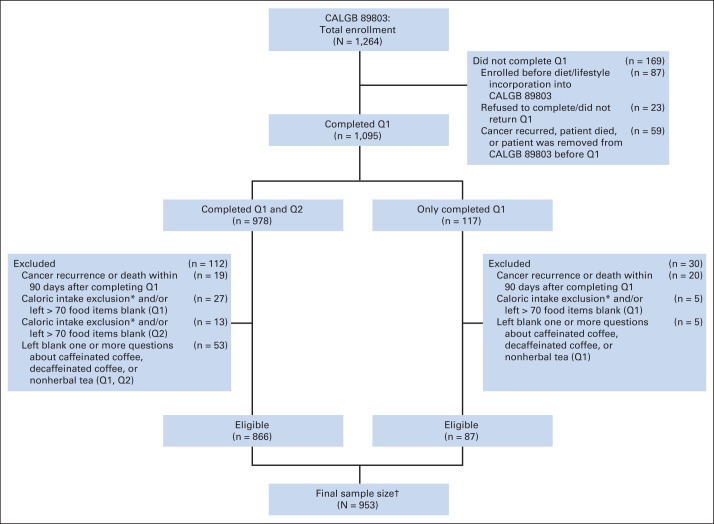

Patients who underwent a complete surgical resection of the primary tumor within 56 days of trial entry, had regional lymph node metastases without evidence of distant metastases, had a baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2,30 and had adequate bone marrow, renal, and hepatic function were eligible. Patients were excluded if they reported significantly abnormal caloric intake (< 600 or > 4,200 calories/d for men; < 500 or > 3,500 calories/d for women), left more than 70 food items blank, or left blank one or more questions about caffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee, or nonherbal tea on Q1 or Q2. Finally, patients were excluded if they had cancer recurrence or death within 90 days of completing the questionnaire to avoid dietary assessment bias because of declining health, resulting in 953 eligible patients (Fig 1). We previously demonstrated that there were no appreciable differences in baseline characteristics between patients eligible for dietary analysis and the remaining patients enrolled onto CALGB 89803 not included in the dietary studies.31 All patients provided study-specific informed consent.

Fig 1.

Derivation of the study cohort. (*) Caloric intake exclusion indicates fewer than 600 calories/d or more than 4,200 calories/d for men, and fewer than 500 calories/d or more than 3,500 calories/d for women. (†) Six patients in the final sample are missing physical activity in questionnaire 1 (Q1; midway through adjuvant therapy), and three are missing physical activity in questionnaire 2 (Q2; 6 months after completion of adjuvant therapy). One patient is missing body mass index in Q2. CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B.

Dietary Assessment

Patients in this analysis completed semiquantitative FFQs that included 131 food items, vitamin and mineral supplements, and open-ended sections for other supplements and foods not specifically listed.32,33 Participants were asked how often, on average, during the previous 3 months, they consumed a specific food portion size, with up to nine possible responses, which ranged from never to six or more times per day. We computed nutrient intakes by multiplying the frequency of consumption of each food by the nutrient content of the specified portions.34,35 Nutrient values were energy adjusted using the residuals methods.36

On each questionnaire, we assessed intake of caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee, nonherbal tea, herbal tea, and different types of caffeinated soft drinks. We assessed total intake of caffeine by summing the caffeine content for a specific amount of each food during the study period (1 cup for coffee or tea, one 12-ounce bottle or can for carbonated beverages, and 1 ounce for chocolate) multiplied by a weight proportional to the frequency of its use.22,35 In a separate validity study of our questionnaire, the correlation coefficients between two 1-week diet records and the FFQs for average intake of coffee and tea were 0.78 and 0.93, respectively.37

Patients who completed the first FFQ (Q1) without cancer recurrence before FFQ completion were included in these analyses. The median time from study entry to Q1 was 3.5 months (95% range, 2.5 to 5.0 months; full range, 0.2 to 9.9 months). We updated dietary exposures on the basis of results of the second FFQ (Q2) using cumulative averaging, as previously described,14,31,38–40 but weighted proportional to times between Q1 and Q2, and then between Q2 and disease-free survival (DFS) time. For example, if a patient completed Q1 at 4 months, completed Q2 at 14 months, and had a cancer recurrence at 30 months, the total time between Q1 and cancer recurrence was 26 months, and 38% of that time was between Q1 and Q2 and 62% of that time was between Q2 and the recurrence.

Study End Points

The primary end point of our study was DFS, defined as time from completion of Q1 to tumor recurrence, occurrence of a new primary colon tumor, or death from any cause. We also assessed recurrence-free survival (RFS), defined as time from completion of Q1 to tumor recurrence or occurrence of a new primary colon tumor. For RFS, patients who died without known tumor recurrence were censored at last documented physician evaluation. Finally, overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from completion of Q1 to death from any cause.

Statistical Analysis

In the clinical trial, there was no statistical difference in either DFS or OS between treatment arms.29 Therefore, data for patients in both arms were combined and analyzed according to frequency categories of dietary intake. We assessed nonherbal tea alone because it is biologically distinct from herbal teas.41 Intake of total coffee, caffeinated coffee, and tea was classified into five frequency categories (0, < 1, 1, 2 to 3, and ≥ 4 cups/d), consistent with previous studies.42–45 Given the few participants reporting decaffeinated coffee intake of more than 2 cups/d, intake of decaffeinated coffee was classified by only four frequency categories to conserve statistical power (0, < 1, 1, and ≥ 2 cups/d).

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to determine the simultaneous impact of other variables potentially associated with each outcome.46 As previously described,36 we used time-varying covariates to adjust for total calories, physical activity as measured in metabolic equivalent task hours per week,47 body mass index calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height squared in meters squared, alcohol consumption in grams per day, energy adjusted, and consumption of Western and prudent pattern diets, as defined previously.14 Other covariates, including sex, age, depth of invasion through bowel wall, number of positive lymph nodes, baseline performance status, treatment group, smoking history (yes, no, missing), and multivitamin use (consistent user, not consistent user, missing), were entered into the model as fixed covariates. In secondary multivariable analyses, we further adjusted for time-varying sugar-sweetened beverage intake and dietary glycemic load.13,31 In analyses assessing caffeinated coffee consumption and decaffeinated coffee consumption as independent covariates, we included both caffeinated coffee and decaffeinated coffee intake in the multivariable model simultaneously; similarly, in analyses of tea intake, we included total coffee consumption in the model. Covariates with missing variables were coded with indicator variables.

Although results are displayed for visual effect in discrete categories, each primary statistical analysis was performed using consumption as a continuous measure to minimize bias created by selected categorization. We tested for linear trends across frequency categories of intake by assigning each participant the median value for each frequency category and modeling this value as a continuous variable, consistent with previous studies.13,14,31 In subgroup exploratory analyses on the effect of total coffee consumption, we collapsed intake into four categories to conserve power, creating the following groupings: 0, less than 1, 1, and 2 or more cups/d. The proportionality of hazards assumption for the effect of each coffee type, caffeine, and tea was satisfied by examining each as a time-dependent covariate in the model. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Data collection and statistical analyses were conducted by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center at Duke University Medical Center. Data quality was ensured by review of data by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center and by the study chairperson following Alliance policies. All analyses were based on the study database frozen on November 9, 2009.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

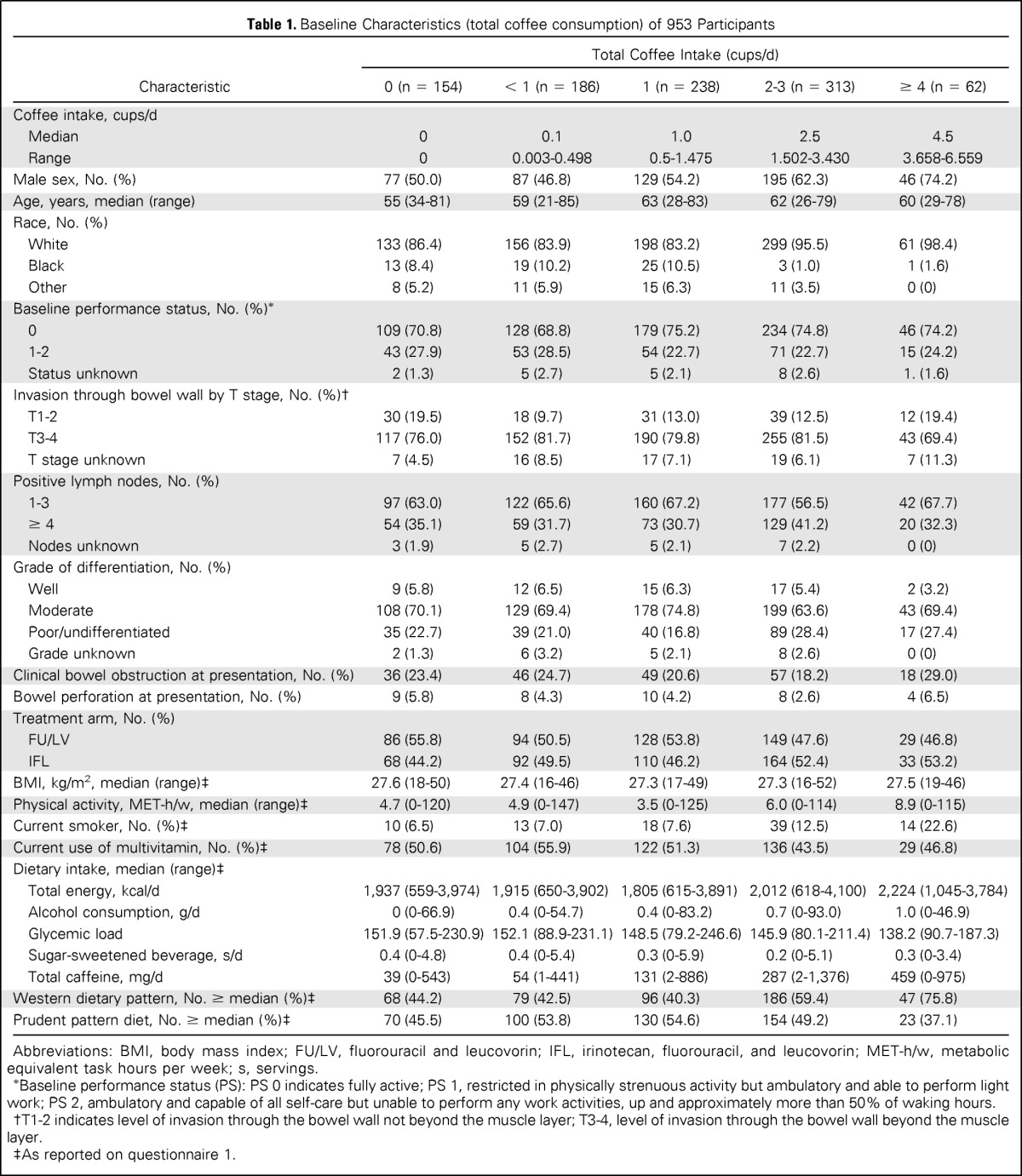

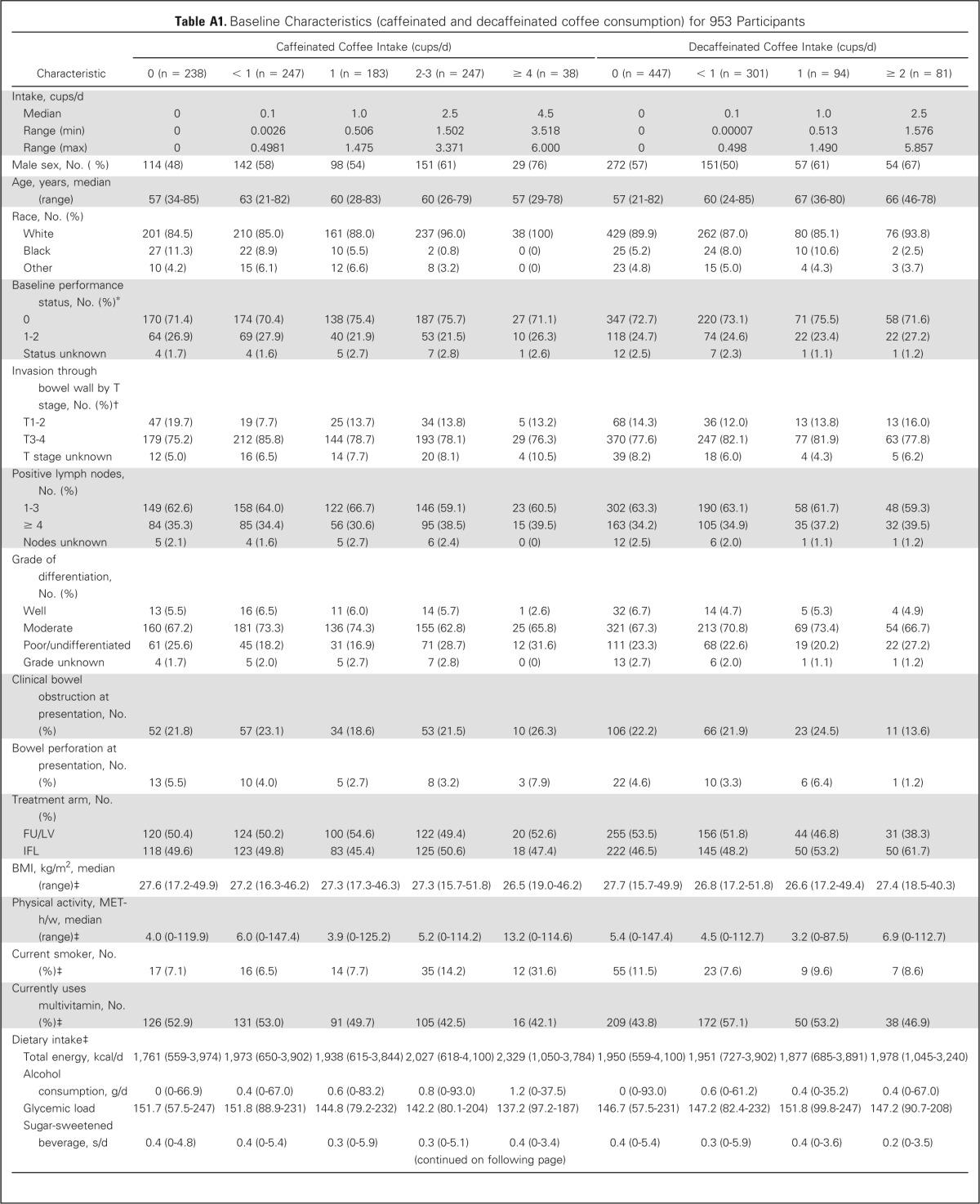

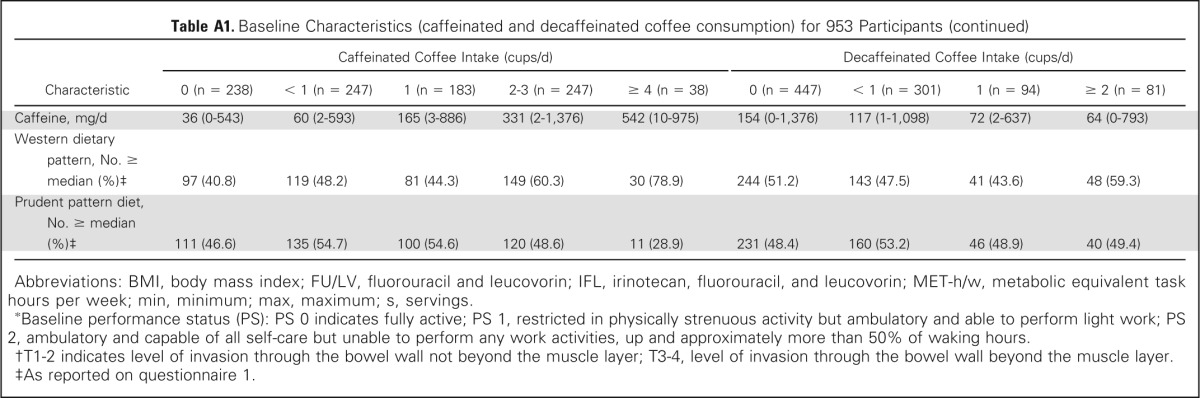

Baseline characteristics by frequency of total coffee consumption are displayed in Table 1. Frequent coffee drinkers were more physically active and more likely to be male, white, and current smokers; had higher intake of total energy, caffeine, and Western pattern diet; and had lower dietary glycemic load and lower prudent pattern diet. Baseline characteristics by frequency of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption are displayed in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (total coffee consumption) of 953 Participants

| Characteristic | Total Coffee Intake (cups/d) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 154) | < 1 (n = 186) | 1 (n = 238) | 2-3 (n = 313) | ≥ 4 (n = 62) | |

| Coffee intake, cups/d | |||||

| Median | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| Range | 0 | 0.003-0.498 | 0.5-1.475 | 1.502-3.430 | 3.658-6.559 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 77 (50.0) | 87 (46.8) | 129 (54.2) | 195 (62.3) | 46 (74.2) |

| Age, years, median (range) | 55 (34-81) | 59 (21-85) | 63 (28-83) | 62 (26-79) | 60 (29-78) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||||

| White | 133 (86.4) | 156 (83.9) | 198 (83.2) | 299 (95.5) | 61 (98.4) |

| Black | 13 (8.4) | 19 (10.2) | 25 (10.5) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 8 (5.2) | 11 (5.9) | 15 (6.3) | 11 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Baseline performance status, No. (%)* | |||||

| 0 | 109 (70.8) | 128 (68.8) | 179 (75.2) | 234 (74.8) | 46 (74.2) |

| 1-2 | 43 (27.9) | 53 (28.5) | 54 (22.7) | 71 (22.7) | 15 (24.2) |

| Status unknown | 2 (1.3) | 5 (2.7) | 5 (2.1) | 8 (2.6) | 1. (1.6) |

| Invasion through bowel wall by T stage, No. (%)† | |||||

| T1-2 | 30 (19.5) | 18 (9.7) | 31 (13.0) | 39 (12.5) | 12 (19.4) |

| T3-4 | 117 (76.0) | 152 (81.7) | 190 (79.8) | 255 (81.5) | 43 (69.4) |

| T stage unknown | 7 (4.5) | 16 (8.5) | 17 (7.1) | 19 (6.1) | 7 (11.3) |

| Positive lymph nodes, No. (%) | |||||

| 1-3 | 97 (63.0) | 122 (65.6) | 160 (67.2) | 177 (56.5) | 42 (67.7) |

| ≥ 4 | 54 (35.1) | 59 (31.7) | 73 (30.7) | 129 (41.2) | 20 (32.3) |

| Nodes unknown | 3 (1.9) | 5 (2.7) | 5 (2.1) | 7 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Grade of differentiation, No. (%) | |||||

| Well | 9 (5.8) | 12 (6.5) | 15 (6.3) | 17 (5.4) | 2 (3.2) |

| Moderate | 108 (70.1) | 129 (69.4) | 178 (74.8) | 199 (63.6) | 43 (69.4) |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 35 (22.7) | 39 (21.0) | 40 (16.8) | 89 (28.4) | 17 (27.4) |

| Grade unknown | 2 (1.3) | 6 (3.2) | 5 (2.1) | 8 (2.6) | 0 (0) |

| Clinical bowel obstruction at presentation, No. (%) | 36 (23.4) | 46 (24.7) | 49 (20.6) | 57 (18.2) | 18 (29.0) |

| Bowel perforation at presentation, No. (%) | 9 (5.8) | 8 (4.3) | 10 (4.2) | 8 (2.6) | 4 (6.5) |

| Treatment arm, No. (%) | |||||

| FU/LV | 86 (55.8) | 94 (50.5) | 128 (53.8) | 149 (47.6) | 29 (46.8) |

| IFL | 68 (44.2) | 92 (49.5) | 110 (46.2) | 164 (52.4) | 33 (53.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range)‡ | 27.6 (18-50) | 27.4 (16-46) | 27.3 (17-49) | 27.3 (16-52) | 27.5 (19-46) |

| Physical activity, MET-h/w, median (range)‡ | 4.7 (0-120) | 4.9 (0-147) | 3.5 (0-125) | 6.0 (0-114) | 8.9 (0-115) |

| Current smoker, No. (%)‡ | 10 (6.5) | 13 (7.0) | 18 (7.6) | 39 (12.5) | 14 (22.6) |

| Current use of multivitamin, No. (%)‡ | 78 (50.6) | 104 (55.9) | 122 (51.3) | 136 (43.5) | 29 (46.8) |

| Dietary intake, median (range)‡ | |||||

| Total energy, kcal/d | 1,937 (559-3,974) | 1,915 (650-3,902) | 1,805 (615-3,891) | 2,012 (618-4,100) | 2,224 (1,045-3,784) |

| Alcohol consumption, g/d | 0 (0-66.9) | 0.4 (0-54.7) | 0.4 (0-83.2) | 0.7 (0-93.0) | 1.0 (0-46.9) |

| Glycemic load | 151.9 (57.5-230.9) | 152.1 (88.9-231.1) | 148.5 (79.2-246.6) | 145.9 (80.1-211.4) | 138.2 (90.7-187.3) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage, s/d | 0.4 (0-4.8) | 0.4 (0-5.4) | 0.3 (0-5.9) | 0.2 (0-5.1) | 0.3 (0-3.4) |

| Total caffeine, mg/d | 39 (0-543) | 54 (1-441) | 131 (2-886) | 287 (2-1,376) | 459 (0-975) |

| Western dietary pattern, No. ≥ median (%)‡ | 68 (44.2) | 79 (42.5) | 96 (40.3) | 186 (59.4) | 47 (75.8) |

| Prudent pattern diet, No. ≥ median (%)‡ | 70 (45.5) | 100 (53.8) | 130 (54.6) | 154 (49.2) | 23 (37.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FU/LV, fluorouracil and leucovorin; IFL, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin; MET-h/w, metabolic equivalent task hours per week; s, servings.

Baseline performance status (PS): PS 0 indicates fully active; PS 1, restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work; PS 2, ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to perform any work activities, up and approximately more than 50% of waking hours.

T1-2 indicates level of invasion through the bowel wall not beyond the muscle layer; T3-4, level of invasion through the bowel wall beyond the muscle layer.

As reported on questionnaire 1.

Impact of Coffee Intake on Cancer Recurrence and Death

The median follow-up time from completion of Q1 is 7.3 years. During follow-up, 329 of the 953 patients in this analysis experienced cancer recurrence or developed new primary tumors; 288 of these patients died. An additional 36 patients died without documented cancer recurrence.

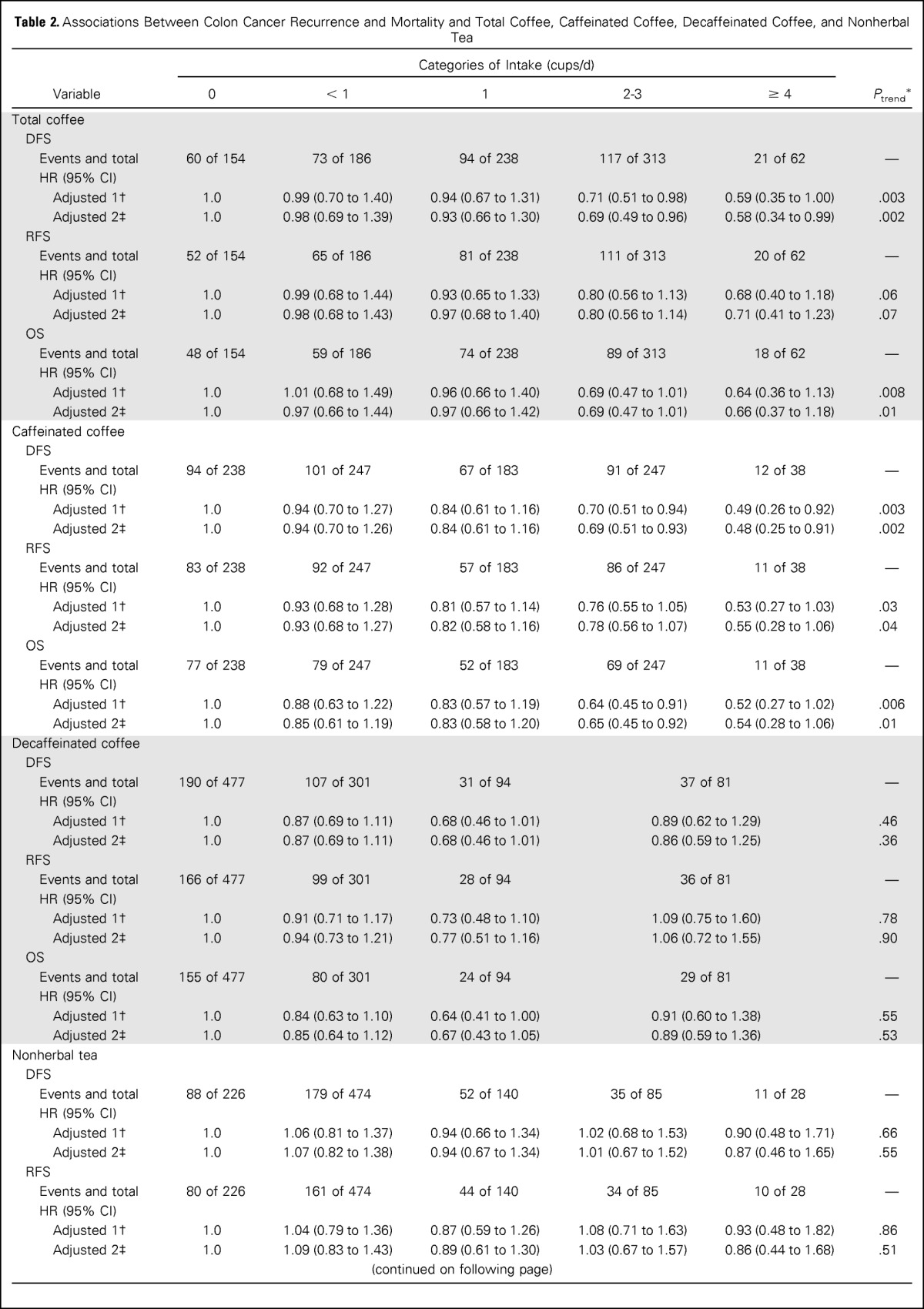

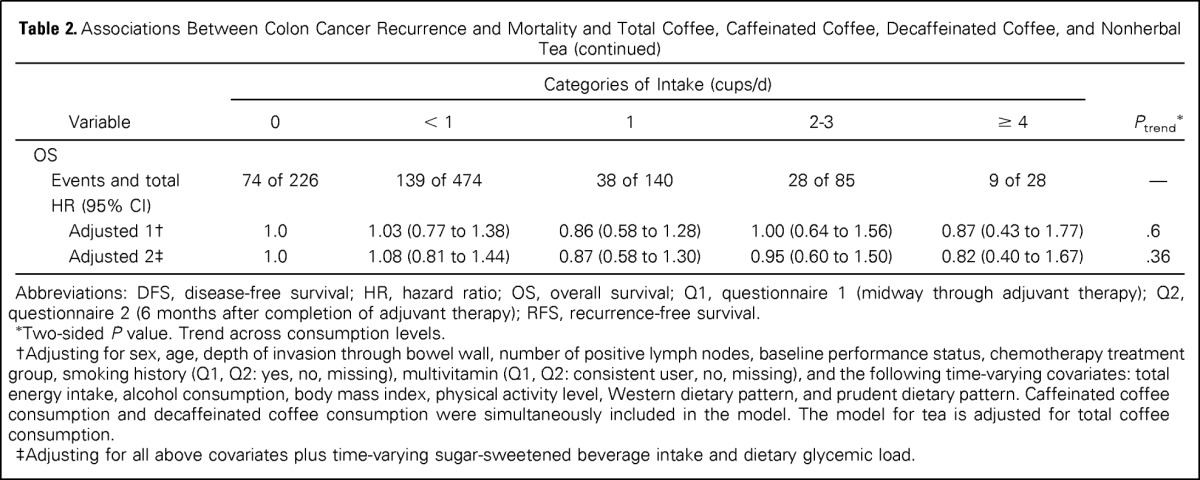

The predefined primary end point in our analysis was DFS. Increasing total coffee intake was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of cancer recurrence or mortality after adjusting for other predictors of cancer recurrence (Table 2). Compared with abstainers, patients who consumed 4 cups/d or more of coffee experienced an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for disease recurrence or mortality of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35 to 1.00; Ptrend = .003). Increasing total coffee intake was also associated with a significant improvement in OS (Ptrend = .008) and a trend toward improved RFS that did not reach statistical significance (Ptrend = .06). These results were largely unchanged when further adjusted for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and glycemic load (DFS, Ptrend = .002; RFS, Ptrend = .07; OS, Ptrend = .01).

Table 2.

Associations Between Colon Cancer Recurrence and Mortality and Total Coffee, Caffeinated Coffee, Decaffeinated Coffee, and Nonherbal Tea

| Variable | Categories of Intake (cups/d) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | < 1 | 1 | 2-3 | ≥ 4 | Ptrend* | |

| Total coffee | ||||||

| DFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 60 of 154 | 73 of 186 | 94 of 238 | 117 of 313 | 21 of 62 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.99 (0.70 to 1.40) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.31) | 0.71 (0.51 to 0.98) | 0.59 (0.35 to 1.00) | .003 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.39) | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.30) | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.96) | 0.58 (0.34 to 0.99) | .002 |

| RFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 52 of 154 | 65 of 186 | 81 of 238 | 111 of 313 | 20 of 62 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.99 (0.68 to 1.44) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.33) | 0.80 (0.56 to 1.13) | 0.68 (0.40 to 1.18) | .06 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.98 (0.68 to 1.43) | 0.97 (0.68 to 1.40) | 0.80 (0.56 to 1.14) | 0.71 (0.41 to 1.23) | .07 |

| OS | ||||||

| Events and total | 48 of 154 | 59 of 186 | 74 of 238 | 89 of 313 | 18 of 62 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.68 to 1.49) | 0.96 (0.66 to 1.40) | 0.69 (0.47 to 1.01) | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.13) | .008 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.97 (0.66 to 1.44) | 0.97 (0.66 to 1.42) | 0.69 (0.47 to 1.01) | 0.66 (0.37 to 1.18) | .01 |

| Caffeinated coffee | ||||||

| DFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 94 of 238 | 101 of 247 | 67 of 183 | 91 of 247 | 12 of 38 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.94 (0.70 to 1.27) | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.16) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.94) | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.92) | .003 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.94 (0.70 to 1.26) | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.16) | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93) | 0.48 (0.25 to 0.91) | .002 |

| RFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 83 of 238 | 92 of 247 | 57 of 183 | 86 of 247 | 11 of 38 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.28) | 0.81 (0.57 to 1.14) | 0.76 (0.55 to 1.05) | 0.53 (0.27 to 1.03) | .03 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.27) | 0.82 (0.58 to 1.16) | 0.78 (0.56 to 1.07) | 0.55 (0.28 to 1.06) | .04 |

| OS | ||||||

| Events and total | 77 of 238 | 79 of 247 | 52 of 183 | 69 of 247 | 11 of 38 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.22) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.19) | 0.64 (0.45 to 0.91) | 0.52 (0.27 to 1.02) | .006 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.85 (0.61 to 1.19) | 0.83 (0.58 to 1.20) | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.92) | 0.54 (0.28 to 1.06) | .01 |

| Decaffeinated coffee | ||||||

| DFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 190 of 477 | 107 of 301 | 31 of 94 | 37 of 81 | — | |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.11) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.29) | .46 | |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.11) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.25) | .36 | |

| RFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 166 of 477 | 99 of 301 | 28 of 94 | 36 of 81 | — | |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.91 (0.71 to 1.17) | 0.73 (0.48 to 1.10) | 1.09 (0.75 to 1.60) | .78 | |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.94 (0.73 to 1.21) | 0.77 (0.51 to 1.16) | 1.06 (0.72 to 1.55) | .90 | |

| OS | ||||||

| Events and total | 155 of 477 | 80 of 301 | 24 of 94 | 29 of 81 | — | |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.84 (0.63 to 1.10) | 0.64 (0.41 to 1.00) | 0.91 (0.60 to 1.38) | .55 | |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 0.85 (0.64 to 1.12) | 0.67 (0.43 to 1.05) | 0.89 (0.59 to 1.36) | .53 | |

| Nonherbal tea | ||||||

| DFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 88 of 226 | 179 of 474 | 52 of 140 | 35 of 85 | 11 of 28 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.06 (0.81 to 1.37) | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.34) | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.53) | 0.90 (0.48 to 1.71) | .66 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.38) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.34) | 1.01 (0.67 to 1.52) | 0.87 (0.46 to 1.65) | .55 |

| RFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 80 of 226 | 161 of 474 | 44 of 140 | 34 of 85 | 10 of 28 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.79 to 1.36) | 0.87 (0.59 to 1.26) | 1.08 (0.71 to 1.63) | 0.93 (0.48 to 1.82) | .86 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.43) | 0.89 (0.61 to 1.30) | 1.03 (0.67 to 1.57) | 0.86 (0.44 to 1.68) | .51 |

| OS | ||||||

| Events and total | 74 of 226 | 139 of 474 | 38 of 140 | 28 of 85 | 9 of 28 | — |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||||

| Adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.38) | 0.86 (0.58 to 1.28) | 1.00 (0.64 to 1.56) | 0.87 (0.43 to 1.77) | .6 |

| Adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.44) | 0.87 (0.58 to 1.30) | 0.95 (0.60 to 1.50) | 0.82 (0.40 to 1.67) | .36 |

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; Q1, questionnaire 1 (midway through adjuvant therapy); Q2, questionnaire 2 (6 months after completion of adjuvant therapy); RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Two-sided P value. Trend across consumption levels.

Adjusting for sex, age, depth of invasion through bowel wall, number of positive lymph nodes, baseline performance status, chemotherapy treatment group, smoking history (Q1, Q2: yes, no, missing), multivitamin (Q1, Q2: consistent user, no, missing), and the following time-varying covariates: total energy intake, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity level, Western dietary pattern, and prudent dietary pattern. Caffeinated coffee consumption and decaffeinated coffee consumption were simultaneously included in the model. The model for tea is adjusted for total coffee consumption.

Adjusting for all above covariates plus time-varying sugar-sweetened beverage intake and dietary glycemic load.

Improved outcomes were also associated with caffeinated coffee consumption. Compared with abstainers, patients who consumed 4 cups/d or more of caffeinated coffee experienced a significant reduction in cancer recurrence or mortality (adjusted HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.92; Ptrend = .003; Table 2). Similarly, increasing consumption of caffeinated coffee was associated with a statistically significant improvement in RFS (Ptrend = .03) and OS (Ptrend = .006). These results remained largely unchanged when adjusted for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and glycemic load (DFS, Ptrend = .002; RFS, Ptrend = .04; OS, Ptrend = .01). In contrast, neither nonherbal tea nor decaffeinated coffee intake was associated with patient outcome. Secondary analyses showed no association of outcomes with herbal or total tea (data not shown).

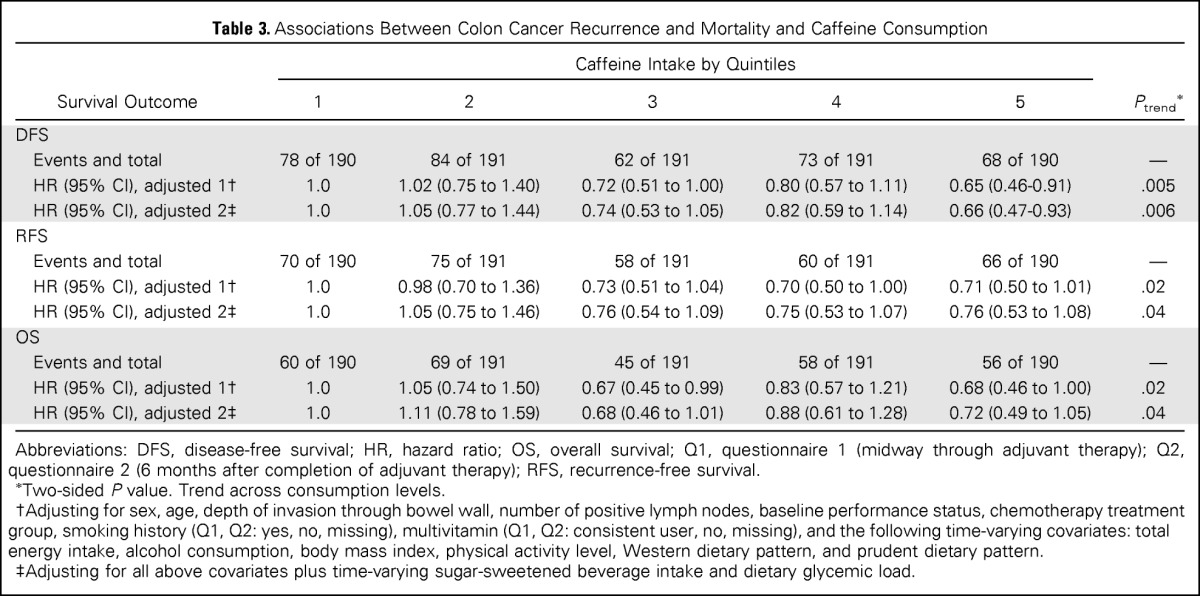

We assessed the influence of total caffeine intake on patient outcome (Table 3). Compared with patients in the lowest quintile of caffeine intake, those in the highest quintile experienced a significant improvement in cancer recurrence or mortality (adjusted HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.91; Ptrend = .005). In addition, increasing caffeine intake was associated with a statistically significant improvement in RFS (Ptrend = .02) and OS (Ptrend = .02). These results remained statistically significant after adjusting for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and glycemic load (DFS, Ptrend = .006; RFS, Ptrend = .04; OS, Ptrend = .04).

Table 3.

Associations Between Colon Cancer Recurrence and Mortality and Caffeine Consumption

| Survival Outcome | Caffeine Intake by Quintiles |

Ptrend* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| DFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 78 of 190 | 84 of 191 | 62 of 191 | 73 of 191 | 68 of 190 | — |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.40) | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.00) | 0.80 (0.57 to 1.11) | 0.65 (0.46-0.91) | .005 |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.05 (0.77 to 1.44) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.05) | 0.82 (0.59 to 1.14) | 0.66 (0.47-0.93) | .006 |

| RFS | ||||||

| Events and total | 70 of 190 | 75 of 191 | 58 of 191 | 60 of 191 | 66 of 190 | — |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 0.98 (0.70 to 1.36) | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.04) | 0.70 (0.50 to 1.00) | 0.71 (0.50 to 1.01) | .02 |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.05 (0.75 to 1.46) | 0.76 (0.54 to 1.09) | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.07) | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.08) | .04 |

| OS | ||||||

| Events and total | 60 of 190 | 69 of 191 | 45 of 191 | 58 of 191 | 56 of 190 | — |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 1† | 1.0 | 1.05 (0.74 to 1.50) | 0.67 (0.45 to 0.99) | 0.83 (0.57 to 1.21) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.00) | .02 |

| HR (95% CI), adjusted 2‡ | 1.0 | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.59) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.28) | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.05) | .04 |

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; Q1, questionnaire 1 (midway through adjuvant therapy); Q2, questionnaire 2 (6 months after completion of adjuvant therapy); RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Two-sided P value. Trend across consumption levels.

Adjusting for sex, age, depth of invasion through bowel wall, number of positive lymph nodes, baseline performance status, chemotherapy treatment group, smoking history (Q1, Q2: yes, no, missing), multivitamin (Q1, Q2: consistent user, no, missing), and the following time-varying covariates: total energy intake, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity level, Western dietary pattern, and prudent dietary pattern.

Adjusting for all above covariates plus time-varying sugar-sweetened beverage intake and dietary glycemic load.

Stratified Analyses

We examined the influence of total coffee intake on DFS across strata of other potential predictors of patient outcome, comparing 2 cups/d or more with 0 to conserve statistical power (Fig 2). The association between total coffee intake and patient outcome seemed consistent across most strata of patient, disease, and treatment characteristics. The association of total coffee intake with improved DFS seemed slightly stronger among patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 to 2, and a test for interaction between total coffee intake and baseline performance status was statistically significant (Pinteraction = .04).

Fig 2.

Multivariable hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for cancer recurrence or mortality across strata of various factors. Analyses used four categories (0, < 1, 1, and ≥ 2 cups/d). The forest plot represents the HRs of the comparison of 2 cups/d or more of total coffee intake with 0 cups/wk, adjusting for sex, age, depth of invasion through bowel wall, number of positive lymph nodes, baseline performance status, chemotherapy treatment group, smoking history (questionnaire 1 [Q1; midway through adjuvant therapy], questionnaire 2 [Q2; 6 months after completion of adjuvant therapy]: yes, no, missing), multivitamin (Q1, Q2: consistent user, no, missing), and the following time-varying covariates: total energy intake, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity level, Western dietary pattern, prudent dietary pattern, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, and dietary glycemic load. FU/LV, fluorouracil plus leucovorin; IFL, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin; MET, metabolic equivalent task. (*) Two-sided P, trend across consumption levels. (†) Two-sided P.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of patients with stage III colon cancer, increasing coffee intake was associated with a significant improvement in cancer recurrence or mortality (DFS) and all-cause mortality (OS). The significant association seemed confined to caffeinated coffee intake. Consistent with this finding, we observed a significant association between higher caffeine intake and improved DFS, RFS, and OS. These associations were independent of other predictors of patient outcome, diet, and lifestyle factors. Moreover, the effect of total coffee intake was largely maintained across other known or suspected predictors of cancer recurrence.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between coffee intake and colon cancer recurrence and survival. We hypothesized that coffee might reduce colon cancer recurrence through improved insulin sensitization and decreased hyperinsulinemia, on the basis of previous studies supporting the role of high-energy balance states in promoting colon cancer recurrence and mortality13,14,16,31 and studies demonstrating an inverse relationship between coffee consumption and risk of T2D.19,20 The precise effect of caffeine on insulin sensitivity is controversial: Although one trial showed caffeine to cause an immediate decrease in insulin sensitivity,48 another trial showed increased adiponectin, an endogenous insulin sensitizer, with caffeinated coffee.24 Most prospective studies and meta-analyses studying the relationship between coffee consumption and risk of T2D have shown an inverse association for both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee.19–21,49 Furthermore, one prospective cohort identified an inverse association between decaffeinated coffee consumption and hemoglobin A1c level.50

Although our findings seemed limited to caffeinated coffee, statistical power to adequately examine decaffeinated coffee was limited. Coffee components beyond caffeine may play a role, such as chlorogenic acid, a hypoglycemic coffee phenol.51,52 Alternatively, coffee and caffeine may affect colon cancer through other mechanisms, such as anti-inflammatory,53 antioxidant,54,55 antiangiogenic, antimetastatic, and proapoptotic effects.56–58

We cannot completely exclude the possibility that the associations between total coffee, caffeinated coffee, and caffeine intake and improved DFS result from confounding variables. However, these associations persisted even after controlling for known or suspected predictors of patient outcome, including physical activity, dietary glycemic load, sugar-sweetened beverage intake, and Western and prudent dietary patterns. Furthermore, the association between coffee and improved DFS remained largely consistent across strata of these other predictors of patient outcome. Nonetheless, data on other potential confounders associated with coffee intake, such as poor sleeping habits, work shifts, and anxiety, were not examined in our trial.

Given that patients who consume coffee after cancer diagnosis may have similarly consumed coffee before diagnosis, we cannot exclude the possibility that coffee drinkers develop biologically less aggressive colon cancers. Nonetheless, we did not observe a meaningful association between coffee intake and tumor-related characteristics associated with cancer recurrence.

Testing for relationships between dietary factors and cancer recurrence and mortality in a large random assignment trial offers several advantages. Patient follow-up and treatment were carefully prescribed in the trial, with regular detailed medical examinations to prospectively record the date and nature of cancer recurrences. At study enrollment, all patients had lymph node–positive, nonmetastatic cancer, reducing impact of heterogeneity by disease stage. Prospective collection of detailed information on other potentially prognostic variables at the time of study enrollment reduced likelihood of reporting bias, facilitating more accurate adjustment for potential confounders. Finally, we updated dietary data 6 months after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy to reflect changes in diet that may have occurred after patients recovered from treatment effects and to reduce random error in reporting of dietary practices through repeated measurements. Any residual random error in reporting of dietary practices would likely bias findings toward the null hypothesis.

We considered the possibility that patients with occult cancer recurrences or other poor prognostic characteristics may have decreased their coffee intake. To minimize this bias, we excluded recurrences or deaths within 3 months of FFQ completion. Furthermore, because patients in this trial underwent comprehensive clinical and radiologic assessment before study enrollment, we would expect few patients to have occult cancer recurrences or other poor prognostic characteristics at baseline. To address potential change in dietary habits over time, we conducted a second FFQ 14 months after resection; nonetheless, we cannot exclude that additional dietary habit changes may have occurred after the second FFQ that were not captured in our analysis. However, any misclassification in dietary habits in our analysis would bias our results toward the null hypothesis. Moreover, previous studies have shown dietary patterns in men to be stable during a 1-year interval,59 and stable in women during 5 years,60 suggesting that dietary patterns may have remained largely stable beyond 24 months after resection. We further recognize that the caffeine content of coffee available across the United States may vary, potentially contributing to measurement error in our analysis; nonetheless, any misclassification in the measurement of caffeine intake would bias our results toward the null hypothesis. In addition, we note the number of patients in our study exceeding 3 cups/d of coffee was relatively small (n = 62); therefore, additional studies should be performed to replicate our findings.

Finally, patients in randomized trials may differ from the general population. However, the distribution of dietary and lifestyle practices reported by our cohort did not differ significantly from those reported in other US cohorts,38 and this cohort, drawn from a large clinical trial, included patients from both community and academic centers throughout North America, improving external validity of our results.

In sum, this prospective study of patients with stage III colon cancer, embedded in a randomized clinical trial, demonstrates improved patient outcome with increased consumption of total coffee, caffeinated coffee, and caffeine. Although our observational study does not offer conclusive evidence for causality, our findings potentially inform colon cancer biology and offer further insight into the role of diet and lifestyle in outcome for patients with colon cancer. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Glossary Terms

- Cox proportional hazards:

See Cox proportional hazards regression model.

- C-peptide:

A protein fragment produced during the enzymatic cleavage of proinsulin to create insulin. It is secreted by pancreatic β-cells at equimolar concentrations to insulin but has a half-life in the circulation of two to five times longer. Because its greater stability in the peripheral circulation, C-peptide has been measured in research studies as a marker of pancreatic β-cell secretory activity.

- Western pattern diet:

Western pattern diet is characterized by high intakes of red and processed meats, fat, refined grains, and dessert.

Appendix

Table A1.

Baseline Characteristics (caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption) for 953 Participants

| Characteristic | Caffeinated Coffee Intake (cups/d) |

Decaffeinated Coffee Intake (cups/d) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 238) | < 1 (n = 247) | 1 (n = 183) | 2-3 (n = 247) | ≥ 4 (n = 38) | 0 (n = 447) | < 1 (n = 301) | 1 (n = 94) | ≥ 2 (n = 81) | |

| Intake, cups/d | |||||||||

| Median | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| Range (min) | 0 | 0.0026 | 0.506 | 1.502 | 3.518 | 0 | 0.00007 | 0.513 | 1.576 |

| Range (max) | 0 | 0.4981 | 1.475 | 3.371 | 6.000 | 0 | 0.498 | 1.490 | 5.857 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 114 (48) | 142 (58) | 98 (54) | 151 (61) | 29 (76) | 272 (57) | 151(50) | 57 (61) | 54 (67) |

| Age, years, median (range) | 57 (34-85) | 63 (21-82) | 60 (28-83) | 60 (26-79) | 57 (29-78) | 57 (21-82) | 60 (24-85) | 67 (36-80) | 66 (46-78) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||||||||

| White | 201 (84.5) | 210 (85.0) | 161 (88.0) | 237 (96.0) | 38 (100) | 429 (89.9) | 262 (87.0) | 80 (85.1) | 76 (93.8) |

| Black | 27 (11.3) | 22 (8.9) | 10 (5.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 25 (5.2) | 24 (8.0) | 10 (10.6) | 2 (2.5) |

| Other | 10 (4.2) | 15 (6.1) | 12 (6.6) | 8 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 23 (4.8) | 15 (5.0) | 4 (4.3) | 3 (3.7) |

| Baseline performance status, No. (%)* | |||||||||

| 0 | 170 (71.4) | 174 (70.4) | 138 (75.4) | 187 (75.7) | 27 (71.1) | 347 (72.7) | 220 (73.1) | 71 (75.5) | 58 (71.6) |

| 1-2 | 64 (26.9) | 69 (27.9) | 40 (21.9) | 53 (21.5) | 10 (26.3) | 118 (24.7) | 74 (24.6) | 22 (23.4) | 22 (27.2) |

| Status unknown | 4 (1.7) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 12 (2.5) | 7 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Invasion through bowel wall by T stage, No. (%)† | |||||||||

| T1-2 | 47 (19.7) | 19 (7.7) | 25 (13.7) | 34 (13.8) | 5 (13.2) | 68 (14.3) | 36 (12.0) | 13 (13.8) | 13 (16.0) |

| T3-4 | 179 (75.2) | 212 (85.8) | 144 (78.7) | 193 (78.1) | 29 (76.3) | 370 (77.6) | 247 (82.1) | 77 (81.9) | 63 (77.8) |

| T stage unknown | 12 (5.0) | 16 (6.5) | 14 (7.7) | 20 (8.1) | 4 (10.5) | 39 (8.2) | 18 (6.0) | 4 (4.3) | 5 (6.2) |

| Positive lymph nodes, No. (%) | |||||||||

| 1-3 | 149 (62.6) | 158 (64.0) | 122 (66.7) | 146 (59.1) | 23 (60.5) | 302 (63.3) | 190 (63.1) | 58 (61.7) | 48 (59.3) |

| ≥ 4 | 84 (35.3) | 85 (34.4) | 56 (30.6) | 95 (38.5) | 15 (39.5) | 163 (34.2) | 105 (34.9) | 35 (37.2) | 32 (39.5) |

| Nodes unknown | 5 (2.1) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (2.7) | 6 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 12 (2.5) | 6 (2.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Grade of differentiation, No. (%) | |||||||||

| Well | 13 (5.5) | 16 (6.5) | 11 (6.0) | 14 (5.7) | 1 (2.6) | 32 (6.7) | 14 (4.7) | 5 (5.3) | 4 (4.9) |

| Moderate | 160 (67.2) | 181 (73.3) | 136 (74.3) | 155 (62.8) | 25 (65.8) | 321 (67.3) | 213 (70.8) | 69 (73.4) | 54 (66.7) |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 61 (25.6) | 45 (18.2) | 31 (16.9) | 71 (28.7) | 12 (31.6) | 111 (23.3) | 68 (22.6) | 19 (20.2) | 22 (27.2) |

| Grade unknown | 4 (1.7) | 5 (2.0) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (2.7) | 6 (2.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Clinical bowel obstruction at presentation, No. (%) | 52 (21.8) | 57 (23.1) | 34 (18.6) | 53 (21.5) | 10 (26.3) | 106 (22.2) | 66 (21.9) | 23 (24.5) | 11 (13.6) |

| Bowel perforation at presentation, No. (%) | 13 (5.5) | 10 (4.0) | 5 (2.7) | 8 (3.2) | 3 (7.9) | 22 (4.6) | 10 (3.3) | 6 (6.4) | 1 (1.2) |

| Treatment arm, No. (%) | |||||||||

| FU/LV | 120 (50.4) | 124 (50.2) | 100 (54.6) | 122 (49.4) | 20 (52.6) | 255 (53.5) | 156 (51.8) | 44 (46.8) | 31 (38.3) |

| IFL | 118 (49.6) | 123 (49.8) | 83 (45.4) | 125 (50.6) | 18 (47.4) | 222 (46.5) | 145 (48.2) | 50 (53.2) | 50 (61.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range)‡ | 27.6 (17.2-49.9) | 27.2 (16.3-46.2) | 27.3 (17.3-46.3) | 27.3 (15.7-51.8) | 26.5 (19.0-46.2) | 27.7 (15.7-49.9) | 26.8 (17.2-51.8) | 26.6 (17.2-49.4) | 27.4 (18.5-40.3) |

| Physical activity, MET-h/w, median (range)‡ | 4.0 (0-119.9) | 6.0 (0-147.4) | 3.9 (0-125.2) | 5.2 (0-114.2) | 13.2 (0-114.6) | 5.4 (0-147.4) | 4.5 (0-112.7) | 3.2 (0-87.5) | 6.9 (0-112.7) |

| Current smoker, No. (%)‡ | 17 (7.1) | 16 (6.5) | 14 (7.7) | 35 (14.2) | 12 (31.6) | 55 (11.5) | 23 (7.6) | 9 (9.6) | 7 (8.6) |

| Currently uses multivitamin, No. (%)‡ | 126 (52.9) | 131 (53.0) | 91 (49.7) | 105 (42.5) | 16 (42.1) | 209 (43.8) | 172 (57.1) | 50 (53.2) | 38 (46.9) |

| Dietary intake‡ | |||||||||

| Total energy, kcal/d | 1,761 (559-3,974) | 1,973 (650-3,902) | 1,938 (615-3,844) | 2,027 (618-4,100) | 2,329 (1,050-3,784) | 1,950 (559-4,100) | 1,951 (727-3,902) | 1,877 (685-3,891) | 1,978 (1,045-3,240) |

| Alcohol consumption, g/d | 0 (0-66.9) | 0.4 (0-67.0) | 0.6 (0-83.2) | 0.8 (0-93.0) | 1.2 (0-37.5) | 0 (0-93.0) | 0.6 (0-61.2) | 0.4 (0-35.2) | 0.4 (0-67.0) |

| Glycemic load | 151.7 (57.5-247) | 151.8 (88.9-231) | 144.8 (79.2-232) | 142.2 (80.1-204) | 137.2 (97.2-187) | 146.7 (57.5-231) | 147.2 (82.4-232) | 151.8 (99.8-247) | 147.2 (90.7-208) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage, s/d | 0.4 (0-4.8) | 0.4 (0-5.4) | 0.3 (0-5.9) | 0.3 (0-5.1) | 0.4 (0-3.4) | 0.4 (0-5.4) | 0.3 (0-5.9) | 0.4 (0-3.6) | 0.2 (0-3.5) |

| Caffeine, mg/d | 36 (0-543) | 60 (2-593) | 165 (3-886) | 331 (2-1,376) | 542 (10-975) | 154 (0-1,376) | 117 (1-1,098) | 72 (2-637) | 64 (0-793) |

| Western dietary pattern, No. ≥ median (%)‡ | 97 (40.8) | 119 (48.2) | 81 (44.3) | 149 (60.3) | 30 (78.9) | 244 (51.2) | 143 (47.5) | 41 (43.6) | 48 (59.3) |

| Prudent pattern diet, No. ≥ median (%)‡ | 111 (46.6) | 135 (54.7) | 100 (54.6) | 120 (48.6) | 11 (28.9) | 231 (48.4) | 160 (53.2) | 46 (48.9) | 40 (49.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FU/LV, fluorouracil and leucovorin; IFL, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin; MET-h/w, metabolic equivalent task hours per week; min, minimum; max, maximum; s, servings.

Baseline performance status (PS): PS 0 indicates fully active; PS 1, restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work; PS 2, ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to perform any work activities, up and approximately more than 50% of waking hours.

T1-2 indicates level of invasion through the bowel wall not beyond the muscle layer; T3-4, level of invasion through the bowel wall beyond the muscle layer.

As reported on questionnaire 1.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health Grants No. U10CA180821 and U10CA180882 to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, CA31946 and CA33601 to the legacy Cancer and Leukemia Group B, and CA180820 to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network. Additional support was provided by Grants No. CA32291, CA77651, CA45808, and CA60138 from National Institutes of Health, by a grant from the Perry S. Levy Fund for Gastrointestinal Cancer Research, and by Pharmacia & Upjohn Company, now Pfizer Oncology. C.S.F. and J.A.M. are supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (Grants No. R01-CA118553, R01-CA149222, R01-CA169141, and P50-CA127003).

Terms in blue are defined in the glossary, found at the end of this article and online at www.jco.org.

The sponsors did not participate in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kaori Sato, Donna Niedzwiecki, Leonard B. Saltz, Robert J. Mayer, Al Benson, Daniel Atienza, Michael Messino, Frank B. Hu, Shuji Ogino, Kana Wu, Walter C. Willett, Edward L. Giovannucci, Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, Charles S. Fuchs

Collection and assembly of data: Kaori Sato, Donna Niedzwiecki, Leonard B. Saltz, Robert J. Mayer, Rex B. Mowat, Renaud Whittom, Al Benson, Daniel Atienza, Michael Messino, Hedy Kindler, Frank B. Hu, Shuji Ogino, Kana Wu, Walter C. Willett, Edward L. Giovannucci, Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, Charles S. Fuchs

Data analysis and interpretation: Brendan J. Guercio, Kaori Sato, Donna Niedzwiecki, Xing Ye, Leonard B. Saltz, Robert J. Mayer, Alexander Hantel, Al Benson, Daniel Atienza, Michael Messino, Hedy Kindler, Alan Venook, Frank B. Hu, Shuji Ogino, Kana Wu, Walter C. Willett, Edward L. Giovannucci, Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, Charles S. Fuchs

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Coffee Intake, Recurrence, and Mortality in Stage III Colon Cancer: Results From CALGB 89803 (Alliance)

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Brendan J. Guercio

No relationship to disclose

Kaori Sato

No relationship to disclose

Donna Niedzwiecki

No relationship to disclose

Xing Ye

No relationship to disclose

Leonard B. Saltz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Abbott Biotherapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Genentech, Pfizer, Bayer AG, Eli Lilly

Research Funding: Taiho Pharmaceutical

Robert J. Mayer

Honoraria: Amgen, AstraZeneca

Rex B. Mowat

No relationship to disclose

Renaud Whittom

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis

Speakers' Bureau: Eli Lilly

Alexander Hantel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech

Al Benson

No relationship to disclose

Daniel Atienza

Employment: Virginia Oncology Associates

Michael Messino

No relationship to disclose

Hedy Kindler

No relationship to disclose

Alan Venook

Research Funding: Bayer AG (Inst), Onyx Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Now-Up-To-Date

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Halozyme Therapeutics, Genentech, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck

Frank B. Hu

No relationship to disclose

Shuji Ogino

No relationship to disclose

Kana Wu

No relationship to disclose

Walter C. Willett

No relationship to disclose

Edward L. Giovannucci

No relationship to disclose

Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt

Research Funding: Biothera (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst)

Charles S. Fuchs

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2029–2043.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannucci E. Diet, body weight, and colorectal cancer: A summary of the epidemiologic evidence. J Womens Health. 2003;12:173–182. doi: 10.1089/154099903321576574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533–2547. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samad A, Taylor R, Marshall T, et al. A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:204–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: A review of the evidence. J Nutr. 2001;131:3109S–3120S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.3109S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaaks R, Toniolo P, Akhmedkhanov A, et al. Serum C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF-binding proteins, and colorectal cancer risk in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1592–1600. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenab M, Riboli E, Cleveland RJ, et al. Serum C-peptide, IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-2 and risk of colon and rectal cancers in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:368–376. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otani T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, et al. Plasma C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding proteins and risk of colorectal cancer in a nested case-control study: The Japan public health center-based prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2007–2012. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei EK, Ma J, Pollak MN, et al. A prospective study of C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1, and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:850–855. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Marchand L, Wang H, Rinaldi S, et al. Associations of plasma C-peptide and IGFBP-1 levels with risk of colorectal adenoma in a multiethnic population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1471–1477. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fung TT, Hu FB, Schulze M, et al. A dietary pattern that is associated with C-peptide and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:959–965. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9969-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demark-Wahnefried W, Platz EA, Ligibel JA, et al. The role of obesity in cancer survival and recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1244–1259. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs MA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake and cancer recurrence and survival in CALGB 89803 (Alliance) PLoS One. 2014;9:e99816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298:754–764. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolpin BM, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, et al. Insulin, the insulin-like growth factor axis, and mortality in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:176–185. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3535–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills KT, Bellows CF, Hoffman AE, et al. Diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer prognosis: A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1304–1319. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a479f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhupathiraju SN, Pan A, Manson JE, et al. Changes in coffee intake and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes: Three large cohorts of US men and women. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1346–1354. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Chen M, et al. Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:569–586. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhupathiraju SN, Pan A, Malik VS, et al. Caffeinated and caffeine-free beverages and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;97:155–166. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.048603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dam RM, Hu FB. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:97–104. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salazar-Martinez E, Willett WC, Ascherio A, et al. Coffee consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu T, Willett WC, Hankinson SE, et al. Caffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and caffeine in relation to plasma C-peptide levels, a marker of insulin secretion, in US women. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1390–1396. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wedick NM, Brennan AM, Sun Q, et al. Effects of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee on biological risk factors for type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2011;10:93. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams CJ, Fargnoli JL, Hwang JJ, et al. Coffee consumption is associated with higher plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with or without type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:504–507. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu X, Bao Z, Zou J, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of cancers: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Ma D, Zhang Y, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:346–357. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Je Y, Liu W, Giovannucci E. Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1662–1668. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: Results of CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zubrod CG, Schneiderman M, Frei E, III, et al. Appraisal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: Comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. J Chronic Dis. 1960;11:7–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyerhardt JA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Findings from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1702–1711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willett WC, Reynolds RD, Cottrell-Hoehner S, et al. Validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire: Comparison with a 1-year diet record. J Am Diet Assoc. 1987;87:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Agriculture ARS. USDA nutrient database for standard reference, release 10. http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp.

- 35.US Department of Agriculture. Agriculture Handbook No. 8 Series. Washington, DC: Department of Agriculture, US Government Printing Office; 1989. Composition of foods: raw, processed, and prepared, 1963-1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: Implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:17–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: The effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:858–867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaud DS, Fuchs CS, Liu S, et al. Dietary glycemic load, carbohydrate, sugar, and colorectal cancer risk in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:138–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh K, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and carbohydrate intake in relation to risk of distal colorectal adenoma in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1192–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: A comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:531–540. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Cancer Institute. Tea and cancer prevention: Strengths and limits of the evidence. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/prevention/tea.

- 42.van Dam RM, Willett WC, Manson JE, et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study in younger and middle-aged US women. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:398–403. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, et al. The role of number of meals, coffee intake, salt and type of cookware on colorectal cancer development in the context of the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:928–935. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugiyama K, Kuriyama S, Akhter M, et al. Coffee consumption and mortality due to all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in Japanese women. J Nutr. 2010;140:1007–1013. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.109314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michels KB, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, et al. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and incidence of colon and rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:282–292. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: Classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keijzers GB, De Galan BE, Tack CJ, et al. Caffeine can decrease insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:364–369. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huxley R, Lee CMY, Barzi F, et al. Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and tea consumption in relation to incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2053–2063. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang WL, Lopez-Garcia E, Li TY, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:810–817. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tunnicliffe JM, Eller LK, Reimer RA, et al. Chlorogenic acid differentially affects postprandial glucose and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide response in rats. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:650–659. doi: 10.1139/h11-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston KL, Clifford MN, Morgan LM. Coffee acutely modifies gastrointestinal hormone secretion and glucose tolerance in humans: Glycemic effects of chlorogenic acid and caffeine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:728–733. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez-Garcia E, van Dam RM, Qi L, et al. Coffee consumption and markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in healthy and diabetic women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:888–893. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svilaas A, Sakhi AK, Andersen LF, et al. Intakes of antioxidants in coffee, wine, and vegetables are correlated with plasma carotenoids in humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:562–567. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olthof MR, Hollman PC, Katan MB. Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid are absorbed in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131:66–71. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bøhn SK, Blomhoff R, Paur I. Coffee and cancer risk, epidemiological evidence, and molecular mechanisms. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:915–930. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.La Vecchia C, Tavani A. Coffee and cancer risk: An update. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2007;16:385–389. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000243853.12728.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nkondjock A. Coffee consumption and the risk of cancer: An overview. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food-frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:243–249. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weismayer C, Anderson JG, Wolk A. Changes in the stability of dietary patterns in a study of middle-aged Swedish women. J Nutr. 2006;136:1582–1587. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]