Abstract

Current vaccinations are effective against encapsulated strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, but they do not protect against nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae (NESp), which is increasing in colonization and incidence of pneumococcal disease. Vaccination with pneumococcal proteins has been assessed for its ability to protect against pneumococcal disease, but several of these proteins are not expressed by NESp. Pneumococcal surface protein K (PspK), an NESp virulence factor, has not been assessed for immunogenic potential or host modulatory effects. Mammalian cytokine expression was determined in an in vivo mouse model and in an in vitro cell culture system. Systemic and mucosal mouse immunization studies were performed to determine the immunogenic potential of PspK. Murine serum and saliva were collected to quantitate specific antibody isotype responses and the ability of antibody and various proteins to inhibit epithelial cell adhesion. Host cytokine response was not reduced by PspK. NESp was able to colonize the mouse nasopharynx as effectively as encapsulated pneumococci. Systemic and mucosal immunization provided protection from colonization by PspK-positive (PspK+) NESp. Anti-PspK antibodies were recovered from immunized mice and significantly reduced the ability of NESp to adhere to human epithelial cells. A protein-based pneumococcal vaccine is needed to provide broad protection against encapsulated and nonencapsulated pneumococci in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance and vaccine escape mutants. We demonstrate that PspK may serve as an NESp target for next-generation pneumococcal vaccines. Immunization with PspK protected against pneumococcal colonization, which is requisite for pneumococcal disease.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccination has been the single most effective means of preventing death by infectious organisms (1). Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is the etiological agent of several human diseases such as pneumonia, sinusitis, otitis media (OM), meningitis, and septicemia (2). The prevalence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) was significantly reduced after the introduction of currently licensed pneumococcal vaccines (3). Pneumococcal vaccines target specific pneumococcal polysaccharide serotypes, 23 in Pneumovax (Pneumovax 23 [PPSV23]; Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) and 13 in Prevnar (Prevnar 13 [PCV13]; Pfizer [formerly Wyeth Pharmaceuticals], New York, NY, USA). With over 90 known antigenically distinct pneumococcal serotypes, there is a significant deficit in vaccine coverage of the serological diversity expressed by the species (4). This coverage gap is widened by the increase in nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae (NESp) carriage since the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) (5). Pneumococcal disease is predicated by carriage, and NESp is associated with cases of OM and conjunctivitis (6–8). NESp cannot be protected against by current vaccine formulations due to the lack of the capsular polysaccharide. Vaccination with a pneumococcal protein antigen can provide broader pneumococcal protection and be more cost-effective to produce, but a suitable candidate that covers the majority of pneumococci has yet to be developed. While numerous protein-based candidates have been tested, such as PspA, PspC, and PcpA, they have been found to be effective to various degrees based on pneumococcal strain (9–12). Combinations of proteins have been found to be more effective and to have broader coverage (13, 14). NESp does not contain the aforementioned proteins, increasing the need for a protein target effective against NESp (15, 16).

Pneumococcal surface proteins are potential targets for immunization due to accessibility and the function of the protein during colonization. Pneumococcal surface proteins are classified by means of surface attachment and include choline binding proteins (CBPs), LPxTG binding proteins, lipoproteins, and nonclassical surface proteins (17, 18). Some of the most well characterized surface proteins are CBP and LPxTG binding proteins (17). These proteins are immunogenic and aid in colonization. Colonization is requisite for pneumococcal disease in encapsulated and nonencapsulated strains (2, 17). Pneumococcal surface protein K (PspK), an LPxTG-anchored surface protein, has been shown to be necessary for colonization in a subset (null capsule clade I) of NESp and plays a role in virulence during experimental OM (19–21). The role of PspK in colonization makes it a potential vaccine target. While we have previously demonstrated an increase in epithelial cell adherence due to PspK, it is unknown if there are other effects PspK exerts during colonization (20).

Pneumococcal surface protein C (PspC), a CBP, shares some sequence identity with PspK (21). PspC has been reported to aid in epithelial cell adhesion, recruitment of immune factors, and regulation of specific cytokines (22, 23). All of these functions are important for initial colonization and persistence in the nasopharynx. The pneumococcus must attach to epithelial cells to effectively colonize the nasopharynx. Once established, the pneumococcal population must persist and survive against the host innate immune response that is triggered by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid (24–27). Activation of the host innate immune response through PAMP recognition is intended to clear bacteria from the nasopharynx through stimulating inflammation and the recruitment of leukocytes (27, 28).

The pneumococcus has evolved methods to downregulate some of these responses. PspC has been shown to downregulate the chemokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) and the macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), which could aid in maintaining a commensal state (23). While it has been shown that PspK does not reduce complement deposition as PspC does, PspK may have an anti-inflammatory effect (20, 29). Once an encapsulated pneumococcal population establishes in the nasopharynx, it can persist for weeks to months with the ultimate clearance of the strain from an antibody-mediated response (30, 31).

How NESp colonize and persist in the nasopharynx is unknown. PspK may perform functions in colonization unrelated to epithelial cell adherence. We examined the ability of NESp to effectively colonize and persist within the mouse nasopharynx along with the effects of PspK on host cytokine responses. Additionally, the potential of PspK as an NESp vaccine target was examined. We demonstrated that NESp can establish long-term colonization, but PspK does not modulate host inflammatory responses. Also, PspK immunization is able to induce significant protection against colonization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 on sheep blood agar (BA) or in Todd-Hewitt broth with 0.5% yeast extract (THY). Strains used in the current study include S. pneumoniae EF3030 (serotype 19F), D39 (serotype 2), PspK-negative (PspK−) strain MNZ85 (NESp), PspK-positive (PspK+) strain MNZ67 (NESp), PspK+ strain MNZ11 (NESp), and PspK− MNZ1131 (mutant of MNZ11) (21, 32, 33). All MNZ strains are carriage isolates from a study of Korean daycare centers, while strain EF3030 (19F) was used because it is a known strain that colonizes and does not disseminate into systemic infections. Isogenic mutant, MNZ1131, was produced by allelic replacement as described previously (21).

Cloning and expression of recombinant PspK.

Recombinant PspK (rPspK) was isolated for initial immunization studies as described previously using the B-PER 6×His fusion protein purification kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) (20). PspC-LXS234 (amino acids [aa] 1 to 455) used for mucosal immunization was isolated as previously described (34). PspA for immunization was isolated through His-tagged protein fusion as previously described (35).

To express PspK in a Gram-positive background for tagless purification, a gene encoding pspK was fused to a gene harboring promoter and signal peptide sequences of the hla gene from Staphylococcus aureus using overlapping PCR. Briefly, PCR was performed to amplify a gene encoding a part of pspK (from nucleotide 32 to 502, excluding a signal peptide sequence at the N terminus and a LPxTG motif at the C terminus) from the MNZ11 chromosomal DNA template using a forward PspK primer (5′-AATCCTGTCGCTAATGCCGAGATGGCATCGACAGCA-3′; the primer sequence overlapping the hla gene is underlined), a reverse PspK primer (5′-GCGCGGATCCTTATTCTTGTTTACCTTTTTTTGCAGC-3′; the BamHI site is underlined), and Platinum Pfx DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies). PCR was performed to amplify a gene harboring a promoter and a signal peptide sequence of the hla gene from the S. aureus chromosomal DNA template using a forward Hla primer (5′-GCGCGAATTCCATTAGAAGCTAACCTATACTC-3′; the EcoRI site is underlined) and a reverse Hla primer (5′-GGCATTAGCGACAGGATTCATT-3′). Overlapping PCR was performed to join the two amplification products above, using the two PCR amplification products as templates and a forward Hla primer and a reverse PspK primer. The resulting PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzymes, ligated into pMK4 vector, and cloned in Escherichia coli DH5α. A cloned plasmid was purified and transformed into S. aureus RN4220. The cloned S. aureus strain was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) overnight at 37°C. The culture supernatant was harvested by centrifugation and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit (EMD Millipore). Concentrated supernatant was equilibrated with ammonium sulfate (35% [vol/vol]). Linear ammonium sulfate gradient (35% to 0%) hydrophobic interaction chromatography was performed using an Octyl-Sepharose column and AKTA pure (GE Healthcare).

Mouse nasopharyngeal colonization.

Six- to eight-week-old C57/BL6 mice were used for colonization studies. Mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane for easier handling. Colonization was achieved through slow administration to the outer nares of 10 μl of Ringer's lactate solution containing 1 × 107 CFU, which is inhaled by the mouse. The inoculum dose was chosen to allow for consistent colonization so differences observed during colonization would be directly related to the ability to colonize. At times, indicated mice were sacrificed, and the nasopharynx was washed with 200 μl of Ringer's lactate solution. This was followed by homogenization of mouse nasal tissue to collect surface-associated bacteria that were not obtained in the wash. Nasal tissue was obtained by decapitation of euthanized mice, denuding of the skull, bisection of the skull behind the eyes, and transverse sectioning of the rostral portion. The nasal passage was then excised with forceps and homogenized in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Samples were plated on BA with 5 μg/ml gentamicin, and the number of CFU of colonizing bacteria was determined. The amount of total colonizing bacteria was obtained through adding bacteria recovered from the nasal wash and the nasal tissue combined. All strains were tested in at least two separate experiments. Studies were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Milliplex cytokine assay.

Production of 32 cytokines and chemokines was analyzed using the quantitative, multiplexed Milliplex multi-analyte panels (MAP) assay according to the manufacturer's protocols (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Five mice per strain were colonized with either MNZ11 or the isogenic PspK mutant MNZ1131 as described above, and nasal washes were collected 2 days postchallenge for cytokine analysis. To avoid the effect of interassay variation, only samples that were analyzed on the same plate were compared statistically. The lower detection limit was 4 pg/ml for all analytes, and intra-assay variability was <10%. Data were collected and analyzed using a Luminex 200 instrument running xPONENT software version 3.1 (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX).

In vitro cytokine detection.

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL8/IL-8) release was measured in cell culture supernatants by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, United Kingdom). Human pharyngeal epithelial cell line Detroit 562 was grown to ∼95% confluence in 6-well plates. Cells were incubated with 1 × 107 CFU, and supernatants were collected 4 h postchallenge and assayed by ELISA. Values represent results of two independent experiments done in triplicate.

Immunization.

Mice were subinguinally immunized with 100 μl of 10 μg recombinant protein suspended in PBS and combined with Imject Alum (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol three times at 1-week intervals. Mice were colonized as described above 3 weeks following the last boost. Mucosal immunizations were administered to anesthetized mice through application to mouse nares of 14 μl of PBS, which contained 10 μg recombinant protein with 4 μg of cholera toxin β subunit (CTB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Mice were immunized weekly for 3 weeks. The mice were rested for 3 weeks after the boost and then challenged intranasally. Serum was collected through retro orbital bleeding, and mouse saliva was collected by an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mg of pilocarpine-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich) in 100 μl of PBS (36).

Levels of PspK-specific antibodies were calculated using standard ELISA protocol compared to the standard curve of known mouse IgG concentration. In brief, 0.3 μg rPspK was coated on 96-well enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoprecipitation assay (EIA/RIA) plates (Costar) overnight. Plates were washed and serum was serially diluted followed by specific antibody detection through mouse Ig-specific antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase.

Epithelial cell adhesion assay.

The epithelial cell adhesion assay was performed as previously described on human pharyngeal epithelial cell line Detroit 562 (20). Inhibition of adhesion was determined by incubating epithelial cells with 10 μg rPspK in 1 ml media for 30 min before addition of bacteria. The inoculum also contained 10 μg/ml of rPspK. Anti-PspK and secretory IgA (sIgA) inhibitory effect was determined by 30-min preincubation of inoculums with serum collected from systemically immunized mice at a 1:200 dilution factor or 10 μg/ml of sIgA.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test on the InStat program (Prism GraphPad) to determine the statistical difference for immunization and epithelial cell adhesion experiments.

RESULTS

Mammalian cytokine response to NESp expressing PspK.

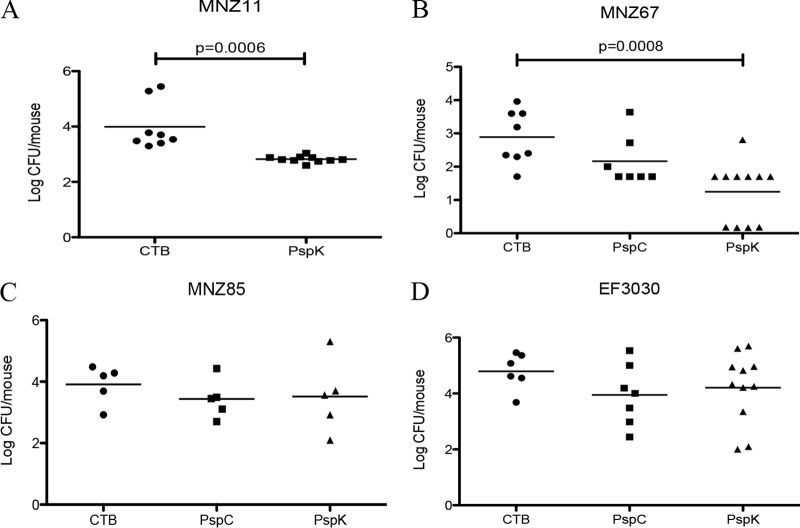

Nasal washes of mice colonized for 48 h with either wild-type MNZ11 (PspK+) or isogenic PspK mutant MNZ1131 were analyzed for cytokine levels using a Milliplex cytokine assay, which quantitates 32 different cytokines in a multiplex reaction. Based on cytokine levels from five mice for each pneumococcal strain tested, there was no statistically significant difference between levels of any of the tested cytokines, with the exception of inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Table 1). Forty-eight hours postchallenge was utilized for analysis to allow sufficient time for surface-associated communities to form but to retain a comparable number of colonizing bacteria. Unfortunately, there were significantly fewer MNZ1131 than MNZ11 (log CFU 3.08 ± 0.12 compared to log CFU 4.01 ± 0.16; P = 0.011) obtained from the nasal washes, explaining why increased levels of TNF-α were observed with MNZ11 colonization. Other proinflammatroy cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), also trended toward increased expression during MNZ11 colonization (Table 1). Since human IL-8 had previously been demonstrated to be modulated by PspC (23), we tested the expression of human IL-8 in an in vitro assay after 4 h of stimulation. Based on analysis of IL-8 levels through an ELISA, there was no significant difference detected between PspK+ MNZ11 and PspK mutant MNZ1131 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Cytokine response of PspK+ NESp compared to that of an isogenic PspK mutant

| Cytokine/chemokinea | MNZ11 (PspK+) pg/ml (mean ± SE) | MNZ1131 (PspK−) pg/ml (mean ± SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eotaxin | 15.85 ± 3.98 | 24.35 ± 2.9 | 0.12 |

| G-CSF | 454.4 ± 95.79 | 407.7 ± 166.04 | 0.80 |

| GM-CSF | 36.6 ± 8.09 | 20.05 ± 3.42 | 0.10 |

| IFN-γ | 66.00 ± 9.63 | 31.65 ± 11.22 | 0.053 |

| IL-1α | 82.7 ± 23.26 | 75.55 ± 28.14 | 0.35 |

| M-CSF | 81.15 ± 28.95 | 44.6 ± 6.55 | 0.25 |

| IL-1β | 22.15 ± 5.58 | 9.15 ± 1.59 | 0.055 |

| IL-2 | 31.7 ± 9.25 | 39.00 ± 17.96 | 0.73 |

| IL-3 | 59.00 ± 4.19 | 40.8 ± 8.13 | 0.08 |

| IL-4 | 27.6 ± 5.66 | 29.3 ± 8.41 | 0.87 |

| IL-5 | 23.2 ± 4.44 | 32.15 ± 10.21 | 0.44 |

| IL-6 | 67.05 ± 16.76 | 26.40 ± 8.47 | 0.06 |

| IL-7 | 41.85 ± 12.10 | 31.6 ± 5.67 | 0.46 |

| IL-9 | 31.25 ± 9.93 | 26.2 ± 6.33 | 0.68 |

| IL-10 | 25.5 ± 3.13 | 16.7 ± 5.1 | 0.18 |

| IL-12 (p40) | 64.95 ± 20.35 | 42.75 ± 18.17 | 0.44 |

| IL-13 | 69.1 ± 7.82 | 54.00 ± 24.63 | 0.58 |

| IL-15 | 37.25 ± 8.11 | 39.95 ± 16.23 | 0.89 |

| IL-17 | 31 ± 6.92 | 29.00 ± 6.45 | 0.84 |

| IP-10 | 28.65 ± 8.18 | 57.55 ± 19.23 | 0.21 |

| MIP-2 | 20.45 ± 4.27 | 32.65 ± 6.63 | 0.16 |

| KC | 312.15 ± 86.04 | 159.65 ± 48.28 | 0.16 |

| LIF | 36.45 ± 10.31 | 28.9 ± 9.55 | 0.61 |

| LIX | 238.25 ± 93.3 | 115.85 ± 19.71 | 0.24 |

| MCP-1 | 32.15 ± 10.6 | 40.75 ± 13.01 | 0.62 |

| MIP-1α | 34.4 ± 9.78 | 19.2 ± 2.64 | 0.17 |

| MIP-1β | 48.15 ± 5.99 | 38.8 ± 10.24 | 0.45 |

| MIG | 12.7 ± 5.17 | 32.45 ± 7.17 | 0.056 |

| RANTES | 97.1 ± 26.55 | 44.8 ± 5.95 | 0.09 |

| TNF-α | 38.00 ± 6.47 | 11.3 ± 5.57 | 0.014 |

| IL-12 (p70) | 41.25 ± 18.09 | 39.5 ± 6.72 | 0.93 |

| VEGF | 494.85 ± 85.3 | 295.1 ± 106.23 | 0.18 |

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IP, interferon-induced protein; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

FIG 1.

Epithelial cell expression of IL-8 after pneumococcal stimulation. IL-8 secretion from Detroit 562 human pharyngeal epithelial cells was stimulated by encapsulated strain D39 (serotype 2) as well as MNZ11 (PspK+) and MNZ1131 (PspK−). Epithelial cells were challenged with 1 × 107 pneumococci, and 4 h postchallenge, supernatants were collected and assayed by ELISA. Results are from two independent experiments done in triplicate and expressed as mean ± standard error (SE).

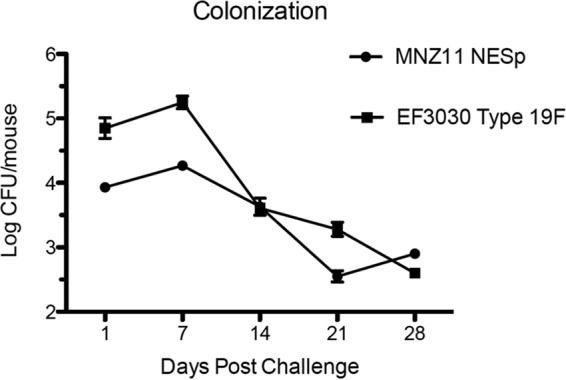

Persistent pneumococcal colonization.

The ability to persist in the mouse nasopharynx was assessed by colonization with either MNZ11 (PspK+) or EF3030 (serotype 19F). There were recoverable bacteria at all times tested for MNZ11 and EF3030 (Fig. 2). While there were significantly more encapsulated bacteria recovered at earlier time points, the general trend of colonization was the same between strains. There was an initial increase in recovered bacteria from day 1 to day 7 followed by decreasing amounts of bacteria to 28 days (Fig. 2). Additionally, persistent colonization by MNZ11 appears to depend on PspK as MNZ1131 (PspK−) is cleared from the nasopharynx after 5 days (21).

FIG 2.

Mouse nasopharyngeal colonization. Mice were challenged with 1 × 107 CFU of pneumococci. Colonization of EF3030 (serotype 19F) and MNZ11 (PspK+) was assessed weekly from a minimum of three mice per strain. Results are expressed as mean ± SE.

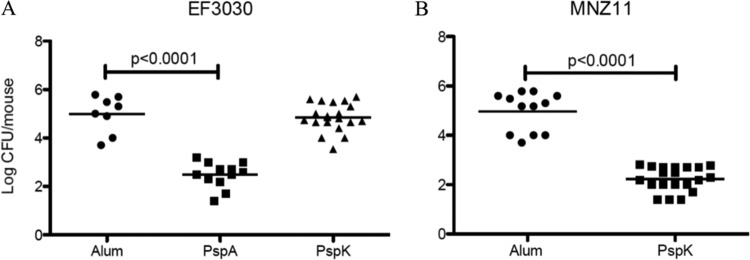

Murine PspK immunization.

Systemic immunization with recombinant protein produced significant protection from colonization in strains expressing PspA for EF3030 and PspK for MNZ11. While complete protection from colonization was not obtained, there was a significant decrease from 4.98 ± 0.27 to 2.48 ± 0.15 (P < 0.0001) in EF3030 recovered from the mouse nasopharynx 5 days postchallenge (Fig. 3A). Immunization of mice with rPspK followed by subsequent challenge with EF3030 had no effect on recovered bacteria, 4.98 ± 0.27 to 4.85 ± 0.13 (Fig. 3A). No effect on EF3030 colonization was achieved by rPspK immunization, but there was a significant decrease from 4.97 ± 0.23 to 2.23 ± 0.11 (P < 0.0001) in recovered MNZ11 (PspK+) (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Systemic immunization with rPspK provides protection from colonization by PspK+ NESp. Groups of mice were immunized weekly for 3 weeks with recombinant protein and rested 3 weeks before intranasal challenge. Bacterial burden was assessed 5 days postchallenge. (A) Immunization with rPspA was able to reduce nasopharyngeal colonization by EF3030 (PspA+), but immunization with rPspK had no effect on EF3030 colonization compared to that of mock-immunized mice. (B) Immunization with rPspK was able to significantly reduce MNZ11 (PspK+) colonization compared to that of mock-immunized mice.

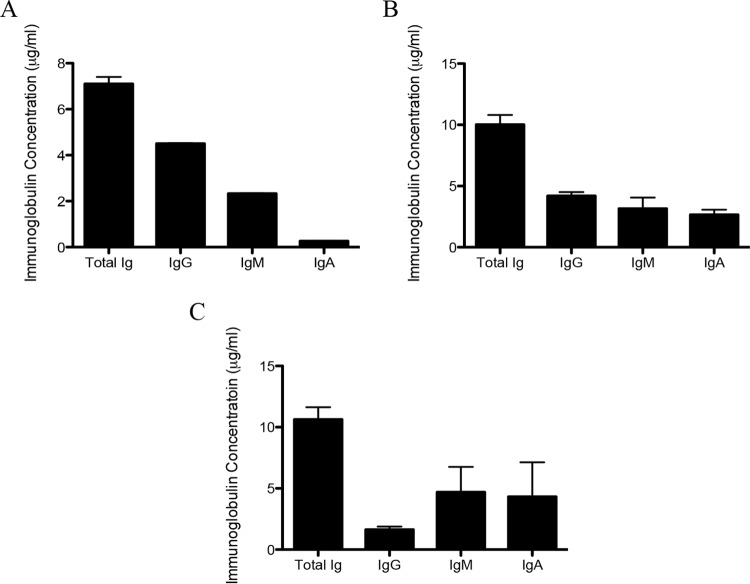

Mucosal immunization with rPspK induced protection from colonization by PspK+ strains MNZ11 and MNZ67. Compared to mock-immunized mice, MNZ11 was carried at higher densities, 3.99 ± 0.31, than that in rPspK-immunized mice, 2.82 ± 0.04 (P = 0.0006) (Fig. 4A). The same degree of protection was observed when mice were challenged with another PspK+ strain (MNZ67, mock immunized, 2.89 ± 0.28, compared to immunized, 1.25 ± 0.27) (P = 0.0008) (Fig. 4B). Carriage of MNZ85, a PspK− NESp strain, was not significantly reduced when immunized with PspC or PspK compared to that of mock immunization, 3.57 ± 0.26 and 3.58 ± 0.50 compared to 3.88 ± 0.24 (Fig. 4C). There was no effect of rPspK immunization on nasopharyngeal carriage when mice are challenged with EF3030 (19F), 4.79 ± 0.27 compared to 4.21 ± 0.38 (Fig. 4D). Immunization with rPspC did not significantly reduced murine colonization when challenged with either MNZ67, 2.17 ± 0.28 compared to 2.89 ± 0.28 (Fig. 4B), or EF3030, 3.95 ± 0.41 compared to 4.79 ± 0.27 (Fig. 4D).

FIG 4.

Mucosal immunization with rPspK provides protection from colonization by PspK+ NESp. Mice were immunized intranasally with recombinant protein and CTB as an adjuvant. Mice received weekly immunizations for 3 weeks, rested 3 weeks, and then were challenged intranasally. (A) A significant reduction in bacterial colonization was observed when mice were mucosally immunized with rPspK and challenged with MNZ11 (PspK+). (B) The same trend is observed when mice were challenged with MNZ67 (PspK+), but protection from rPspC immunization was not observed. (C) No reduction in bacterial colonization was observed when mice were immunized with either rPspC or rPspK and challenged with MNZ85 (PspK−). (D) Mice challenged with EF3030 had no significant reduction in bacteria recovered when immunized with either rPspC or rPspK compared to control.

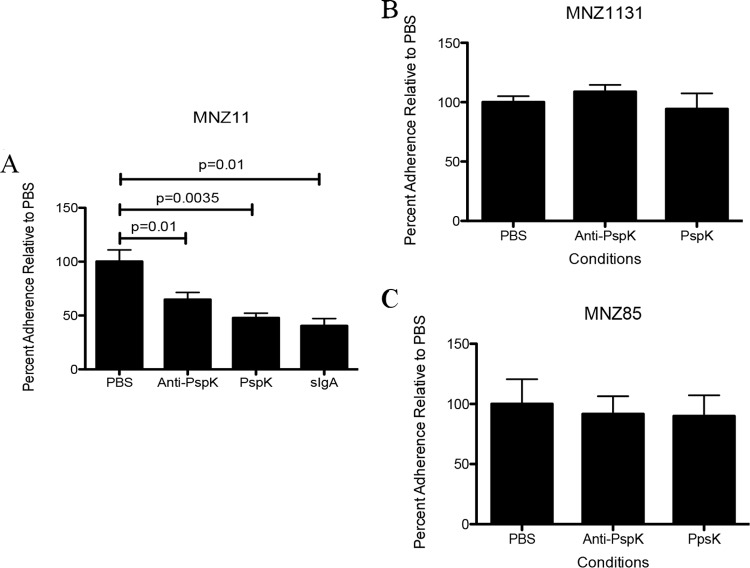

PspK immunization isotype response.

Serum from mice either systemically or mucosally immunized and saliva from mucosally immunized mice were collected and PspK-specific antibody isotypes were determined. PspK-specific antibodies of all isotypes tested, IgG, IgM, and IgA, were isolated from all samples. Mice systemically immunized with rPspK contained 4.5 μg/ml, 2.33 μg/ml, and 0.265 μg/ml of each isotype, respectively (Fig. 5A). Mice mucosally immunized with rPspK contained each isotype tested in mouse serum (Fig. 5B), while antibodies in saliva of each isotype are shown in Fig. 5C.

FIG 5.

Antibody isotype response to rPspK immunization in mice. (A) Systemic immunization with rPspK led to PspK-specific antibody response. ELISA was used to determined PspK-specific serum IgG, IgM, and IgA levels. (B) Mucosal immunization with rPspK led to PspK-specific antibodies in mouse serum. (C) Mucosal immunization with rPspK led to PspK-specific antibody response in murine saliva. All samples were collected 3 weeks after the last immunization from a minimum of three mice. Anti-PspK antibodies were assayed in duplicate for each sample by ELISA. The results are expressed as the mean ± SE.

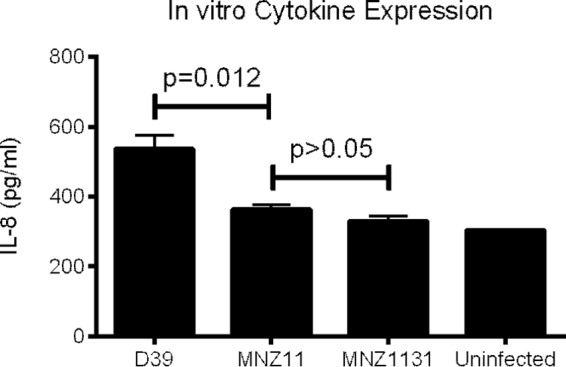

Inhibition of epithelial cell adhesion.

We examined the ability of proteins or antibodies to inhibit epithelial cell adhesion of NESp based on the presence of PspK, in a PspK+ strain (MNZ11), a strain naturally lacking PspK (MNZ85), or a PspK deletion mutant (MNZ1131). Epithelial cell adhesion of MNZ11 was significantly reduced when incubated with an anti-PspK antibody from mice, rPspK, and sIgA from human colostrum. Compared to control epithelial cell adhesion of MNZ11 set at 100%, there were 32.22%, 52.22%, and 59.62% reductions in adhesion, respectively (P = 0.01, P = 0.0035, P = 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 6A). No significant difference was seen in the ability of either MNZ85 or MNZ1131 to adhere to epithelial cells under any of the conditions tested (Fig. 6B and C).

FIG 6.

Epithelial cell adherence reduced by antibodies. (A) Significant inhibition of epithelial cell adhesion by MNZ11 (PspK+) occurred when cells were incubated with either anti-PspK antibodies, rPspK, or sIgA. (B) Epithelial cell adhesion of PspK mutant MNZ1131 was not affected by any of the conditions tested. (C) Epithelial cell adhesion by NESp strain MNZ85, which naturally lacks PspK, was not affected by any of the conditions tested.

DISCUSSION

PspK+ NESp persistently colonized the mouse nasopharynx, and immunization with PspK induced protective antibodies. We did not detect significant reduction of host inflammatory responses by PspK+ NESp. It is important to understand the role of PspK in colonization, as it is the only known NESp-specific virulence factor. NESp strains are increasing in prevalence, in nasopharyngeal colonization, and in disease (5, 6, 37). Nasopharyngeal colonization is requisite for pneumococcal disease, and the ability to persist in the nasopharynx increases the potential for a colonizing strain to invade sterile sites and cause disease. During initial colonization, there are numerous host factors the pneumococcus must evade (38, 39).

PspK contains an R1 and R2 region similar to PspC that comprises ∼15% of the pspK gene. PspC has been reported to aid in adhesion, recruitment of immune factors, and regulation of specific cytokines (22, 23). All of these functions are important for initial colonization along with persisting in the nasopharynx. The pneumococcal capsule has been reported to be required for effective colonization (40, 41). It has been shown to reduce clearance from the nasopharynx by hindering agglutination in the host mucous. Expression levels of the capsule vary during colonization, which allows for attachment mediated by surface proteins (41). The mechanisms that NESp use to colonize the human nasopharynx are not fully understood (5, 21).

Due to localized sequence identity of PspK with PspC, we hypothesized that PspK may modulate host inflammatory responses. However, we were unable to detect any significant reduction in inflammatory response between a PspK+ NESp or a PspK isogenic mutant during mouse colonization (Table 1). While inflammatory response was not reduced, an increase in TNF-α was observed, probably due to increased amount of bacteria recovered from the nasopharynx. Increased trends in other inflammatory cytokines were also observed. Despite this, downstream signaling pathways may be inhibited by PspK-induced signaling because migration inhibition factor (MIG), eotaxin, and MIP-2 were trending toward reduced levels. Interestingly, while IFN-γ trends toward higher levels with MNZ11 (PspK+), MIG, whose production is stimulated by IFN-γ, trends toward lower expression levels when PspK is present (Table 1). The presence of PspC has been shown to downregulate IL-8 production in an in vitro model system (23). We failed to detect PspK modulation of IL-8 using a similar approach. Since the examined strains of NESp lack PspC, some means for regulating the host immune response would be important for persistent colonization. Therefore, NESp must use another mechanism, such as potentially increased biofilm formation, which acapsular strains are known to make in excess compared to their encapsulated counterparts (42–44).

We determined that an NESp strain expressing PspK was able to persistently colonize the mouse nasopharynx. During colonization, the host is exposed to the bacterial surface, allowing for specific antibody responses. Thus, we determined if antibodies to PspK would protect against colonization. Whether we immunized systemically or mucosally, we were able to induce the production of protective antibodies in mice that were specific to PspK (Fig. 3 and 4). Given the localized sequence identity between PspC and PspK, we hypothesized that protection from PspK+ strain colonization may be induced by PspC immunization. We chose to focus on mucosal immunization, as it would induce the strongest response against colonizing strains. Colonization by NESp was not reduced by PspC immunization. Structural differences between PspC and PspK may limit exposure to homologous regions, resulting in protective epitopes being differentially exposed between proteins. We also determined the concentration of anti-PspK antibodies and the isotypes produced against PspK. We found that the relative concentrations of different isotypes of antibodies produced against PspK were similar to what has been seen for other pneumococcal surface proteins (45–47).

The identification of novel targets for immunization against S. pneumoniae is necessary due to emerging serotypes and increasing numbers of NESp isolates (5, 48, 49). The unique characteristics of strains of NESp, which seem to have a different surface structure than encapsulated strains based on sequence analysis and recent reports, require vaccine targets that may be specific for NESp (7, 15, 16). PspK has been shown to be a surface-exposed colonization factor and, more recently, a virulence factor for OM, making it an ideal candidate for vaccination (19, 20). While PspK may be included in next-generation pneumococcal vaccines, PspK will not protect against all NESp since not all strains have this antigen. Serum from mice immunized with PspK was able to reduce epithelial cell adherence of strains expressing PspK indicating that initial host interaction is disrupted by immunization. Reducing colonization by limiting epithelial cell attachment prevents invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease. Also, we found that anti-PspK antibodies do not reduce epithelial cell adhesion of NESp strains that lack PspK. The NESp strains that naturally lack PspK have been shown to cause OM at a lower frequency than PspK+ stains but have also been isolated from invasive infections (19, 37). This further increases the need for future research into NESp-specific vaccines or a general pneumococcal vaccine that is effective against encapsulated and NESp strains.

NESp strains are an increasing proportion of the pneumococcal population. With the implementation of widespread PCV use in underdeveloped countries, there is an even greater chance that NESp may become more common within the human population. The pneumococcus, once a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, has been well contained within developed countries due to prolific PCV use. This highly adaptive bacterial species now harbors antibiotic resistance to most antibiotics and can once again become a significant pathogen in the developed world due to our inability to effectively treat and now effectively vaccinate against certain pneumococcal strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jessica M. Friley, Jessica L. Bradshaw, and Haley Pipkin for collection and processing of colonization samples. We also thank David E. Briles for the recombinant PspA used for immunization.

Funding was provided, in part, by institutional funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Panhuis WG, Grefenstette J, Jung SY, Chok NS, Cross A, Eng H, Lee BY, Zadorozhny V, Brown S, Cummings D, Burke DS. 2013. Contagious diseases in the United States from 1888 to the present. N Engl J Med 369:2152–2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1215400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musher DM. 1992. Infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae: clinical spectrum, pathogenesis, immunity, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 14:801–809. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, Elvin L, Ensor KM, Hackell J, Siber G. 2000. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 19:187–195. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calix JJ, Porambo RJ, Brady AM, Larson TR, Yother J, Abeygunwardana C, Nahm MH. 2012. Biochemical, genetic, and serological characterization of two capsule subtypes among Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 20 strains: discovery of a new pneumococcal serotype. J Biol Chem 287:27885–27894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sa-Leao R, Nunes S, Brito-Avo A, Frazao N, Simoes AS, Crisostomo MI, Paulo AC, Saldanha J, Santos-Sanches I, de Lencastre H. 2009. Changes in pneumococcal serotypes and antibiotypes carried by vaccinated and unvaccinated day-care centre attendees in Portugal, a country with widespread use of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Microbiol Infect 15:1002–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croney CM, Nahm MH, Juhn SK, Briles DE, Crain MJ. 2013. Invasive and noninvasive Streptococcus pneumoniae capsule and surface protein diversity following use of conjugate vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:1711–1718. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00381-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentino MD, McGuire AM, Rosch JW, Bispo PJM, Burnham C, Sanfilippo CM, Carter RA, Zegans ME, Beall B, Earl AM, Tuomanen EI, Morris TW, Haas W, Gilmore MS. 2014. Unencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae from conjunctivitis encode variant traits and belong to a distinct phylogenetic cluster. Nat Commun 5:5411. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Q, Kaur R, Casey JR, Sabharwal V, Pelton S, Pichichero ME. 2011. Nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae as an otopathogen. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 69:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balachandran P, Brooks-Walter A, Virolainen-Julkunen A, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE. 2002. Role of pneumococcal surface protein C in nasopharyngeal carriage and pneumonia and its ability to elicit protection against carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 70:2526–2534. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2526-2534.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glover DT, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein PcpA elicits protection against lung infection and fatal sepsis. Infect Immun 76:2767–2776. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01126-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDaniel LS, Sheffield JS, Delucchi P, Briles DE. 1991. PspA, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, is capable of eliciting protection against pneumococci of more than one capsular type. Infect Immun 59:222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H-Y, Nahm MH, Guo Y, Russell MW, Briles DE. 1997. Intranasal immunization of mice with PspA (pneumococcal surface protein A) can prevent intranasal carriage, pulmonary infection, and sepsis with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 175:839–846. doi: 10.1086/513980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogunniyi AD, Folland RL, Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC. 2000. Immunization of mice with combinations of pneumococcal virulence proteins elicits enhanced protection against challenge with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 68:3028–3033. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.5.3028-3033.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogunniyi AD, Grabowicz M, Briles DE, Cook J, Paton JC. 2007. Development of a vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease based on combinations of virulence proteins of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 75:350–357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01103-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller LE, Thomas JC, Luo X, Nahm MH, McDaniel LS, Robinson DA. 2013. Draft genome sequences of five multilocus sequence types of nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae. Genome Announc 1(4):e00520-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavares D, Simoes A, Bootsma H, Hermans P, de Lencastre H, Sa-Leao R. 2014. Non-typeable pneumococci circulating in Portugal are of cps type NCC2 and have genomic features typical of encapsulated isolates. BMC Genomics 15:863. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergmann S, Hammerschmidt S. 2006. Versatility of pneumococcal surface proteins. Microbiology 152:295–303. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammerschmidt S. 2006. Adherence molecules of pathogenic pneumococci. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller LE, Friley J, Dixit C, Nahm MH, McDaniel LS. 2014. Nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae cause acute otitis media in the chinchilla that is enhanced by pneumococcal surface protein K. Open Forum Infect Dis 1(2):ofu037. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller LE, Jones CV, Thornton JA, Sanders ME, Swiatlo E, Nahm MH, Park IH, McDaniel LS. 2013. PspK of Streptococcus pneumoniae increases adherence to epithelial cells and enhances nasopharyngeal colonization. Infect Immun 81:173–181. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00755-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park IH, Kim KH, Andrade AL, Briles DE, McDaniel LS, Nahm MH. 2012. Nontypeable pneumococci can be divided into multiple cps types, including one type expressing the novel gene pspK. mBio 3(3):e00035-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dave S, Carmicle S, Hammerschmidt S, Pangburn MK, McDaniel LS. 2004. Dual roles of PspC, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, in binding human secretory IgA and factor H. J Immunol 173:471–477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham RMA, Paton JC. 2006. Differential role of CbpA and PspA in modulation of in vitro CXC chemokine responses of respiratory epithelial cells to infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 74:6739–6749. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00954-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durand SH, Flacher V, Roméas A, Carrouel F, Colomb E, Vincent C, Magloire H, Couble M-L, Bleicher F, Staquet M-J, Lebecque S, Farges J-C. 2006. Lipoteichoic acid increases TLR and functional chemokine expression while reducing dentin formation in in vitro differentiated human odontoblasts. J Immunol 176:2880–2887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medzhitov R, Janeway C Jr. 2000. Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev 173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verhoef J, Mattsson E. 1995. The role of cytokines in gram-positive bacterial shock. Trends Microbiol 3:136–140. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)88902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshie O, Imai T, Nomiyama H. 2001. Chemokines in immunity. Adv Immunol 78:57–110. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(01)78002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. 2004. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarva H, Janulczyk R, Hellwage J, Zipfel PF, Björck L, Meri S. 2002. Streptococcus pneumoniae evades complement attack and opsonophagocytosis by expressing the pspC locus-encoded Hic protein that binds to short consensus repeats 8-11 of factor H. J Immunol 168:1886–1894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwaltney JM, Sande MA, Austrian R, Hendley JO. 1975. Spread of Streptococcus pneumoniae in families. II. Relation of transfer of S. pneumoniae to incidence of colds and serum antibody. J Infect Dis 132:62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loda FA, Collier AM, Glezen WP, Strangert K, Clyde WA Jr, Denny FW. 1975. Occurrence of Diplococcus pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of children. J Pediatr 87:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(75)80120-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC, Ades EW, Novak L, van Ginkel FW, Benjamin WH. 2003. Immunizations with pneumococcal surface protein A and pneumolysin are protective against pneumonia in a murine model of pulmonary infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 188:339–348. doi: 10.1086/376571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avery OT, MacLeod CM, McCarty M. 1944. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III. J Exp Med 79:137–158. doi: 10.1084/jem.79.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks-Walter A, Briles DE, Hollingshead SK. 1999. The pspC gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae encodes a polymorphic protein, PspC, which elicits cross-reactive antibodies to PspA and provides immunity to pneumococcal bacteremia. Infect Immun 67:6533–6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He X, McDaniel LS. 2007. The genetic background of Streptococcus pneumoniae affects protection in mice immunized with PspA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 269:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malley R, Trzcinski K, Srivastava A, Thompson CM, Anderson PW, Lipsitch M. 2005. CD4+ T cells mediate antibody-independent acquired immunity to pneumococcal colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:4848–4853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501254102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park IH, Geno KA, Sherwood LK, Nahm MH, Beall B. 2014. Population-based analysis of invasive nontypeable pneumococci reveals that most have defective capsule synthesis genes. PLoS One 9(5):e97825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rossum AMC, Lysenko ES, Weiser JN. 2005. Host and bacterial factors contributing to the clearance of colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae in a murine model. Infect Immun 73:7718–7726. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7718-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Clarke TB, Weiser JN. 2009. Cellular effectors mediating Th17-dependent clearance of pneumococcal colonization in mice. J Clin Invest 119:1899–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magee AD, Yother J. 2001. Requirement for capsule in colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 69:3755–3761. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3755-3761.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson AL, Roche AM, Gould JM, Chim K, Ratner AJ, Weiser JN. 2007. Capsule enhances pneumococcal colonization by limiting mucus-mediated clearance. Infect Immun 75:83–90. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01475-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allegrucci M, Hu FZ, Shen K, Hayes J, Ehrlich GD, Post JC, Sauer K. 2006. Phenotypic characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm development. J Bacteriol 188:2325–2335. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2325-2335.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allegrucci M, Sauer K. 2008. Formation of Streptococcus pneumoniae non-phase-variable colony variants is due to increased mutation frequency present under biofilm growth conditions. J Bacteriol 190:6330–6339. doi: 10.1128/JB.00707-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waite RD, Struthers JK, Dowson CG. 2001. Spontaneous sequence duplication within an open reading frame of the pneumococcal type 3 capsule locus causes high-frequency phase variation. Mol Microbiol 42:1223–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang HY, Srinivasan J, Curtiss R. 2002. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect Immun 70:1739–1749. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1739-1749.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan AQ, Shen Y, Wu Z-Q, Wynn TA, Snapper CM. 2002. Endogenous pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines differentially regulate an in vivo humoral response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 70:749–761. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.749-761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto M, McDaniel LS, Kawabata K, Briles DE, Jackson RJ, McGhee JR, Kiyono H. 1997. Oral immunization with PspA elicits protective humoral immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun 65:640–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McEllistrem MC, Nahm MH. 2012. Novel pneumococcal serotypes 6C and 6D: anomaly or harbinger. Clin Infect Dis 55:1379–1386. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliver MB, van der Linden MPG, Küntzel SA, Saad JS, Nahm MH. 2013. Discovery of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6 variants with glycosyltransferases synthesizing two differing repeating units. J Biol Chem 288:25976–25985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.480152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]