Abstract

Background:

Fingolimod (FTY) is the first oral medication approved for multiple sclerosis therapy. Until now, little has been known about the effects of FTY withdrawal regarding disease activity and development of tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs), as already described in patients who discontinue natalizumab.

Methods:

In this study we present the clinical and radiological findings of two patients who had a severe rebound after FTY withdrawal and compare these with patients identified by a PubMed data bank analysis using the search term ‘fingolimod rebound’. In total, 10 patients, of whom three developed TDLs, are presented.

Results:

Patients suffering from TDLs were free of clinical and radiological signs of disease activity under FTY therapy (100% versus 57%, compared with patients without TDLs) and had rebounds after a mean of 14.6 weeks (standard deviation 11.5) [patients without TDLs 11.7 (standard deviation 3.4)].

Conclusion:

We propose that a good therapeutic response to FTY might be predisposing for a severe rebound after withdrawal. Consequently, therapy switches should be planned carefully with a short therapy free interval.

Keywords: disease-modifying therapy, FTY/fingolimod response, FTY withdrawal/discontinuation, multiple sclerosis, rebound, therapy switch

Case series

The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, fingolimod (FTY), was the first oral medication approved for treatment of relapsing remitting (RR) multiple sclerosis (MS) [Lucchinetti et al. 2008]. FTY reduces the annual relapse rate (ARR) by about 50% [Calabresi et al. 2014] and is approved in the European Union for treatment of highly active RRMS. As rebounds of disease activity are described in RRMS patients after withdrawal of highly effective drugs – especially after natalizumab (Nat) discontinuation [Sorensen et al. 2014], the question arises whether MS rebounds might also occur after FTY discontinuation and whether these cases share similarities which may be helpful to identify patients at risk for a rebound after FTY withdrawal.

We present two cases with severe MS rebounds including TDLs after FTY withdrawal and compare these with eight other published cases found using the search term ‘fingolimod rebound’ in the PubMed database (seven publications). Tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs) are over 0.2 cm in size in T2-weighted and FLAIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences hyperintense lesions. They are characterized by ring enhancement with gadolinium and resemble either an abscess or a tumor. Yet there is no clear definition criteria for TDLs [Ernst et al. 1998; Dastgir and Dimario, 2009]. In the natural course of the disease, patients with initial TDLs and lesion size >5 cm rather exhibit a ‘normal disease course of MS’ on follow up or even better with disease duration >10 years, as objectified by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [Lucchinetti et al. 2008].

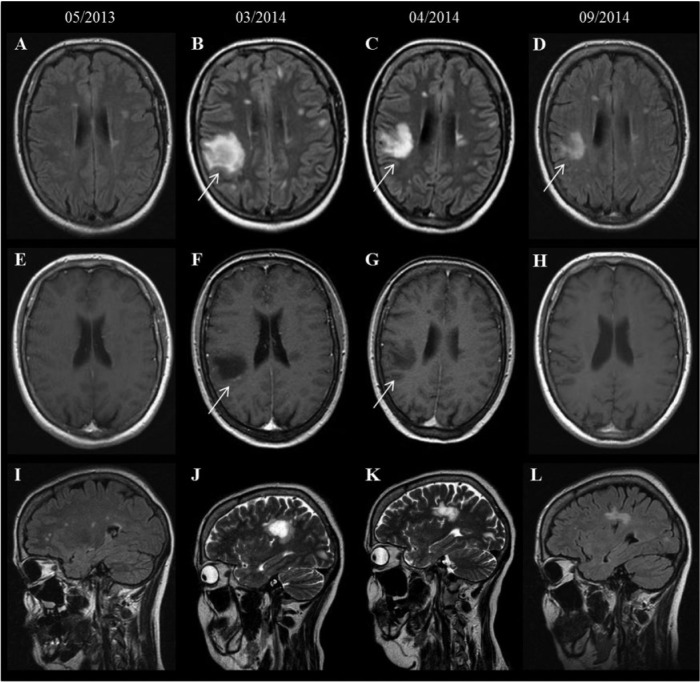

First, we present the case of a 44-year-old Caucasian woman. MS was diagnosed in 2008 (age of onset: 38 years) and interferon (IFN) β1a intramuscular (i.m.) therapy was initiated. Due to intolerable muscle cramps and a worsening of gait ataxia, IFN-β1a was withdrawn in October 2012. After a therapy-free interval of 2 weeks, FTY was initiated in November 2012. During FTY treatment, the patient was free of clinical and radiological signs of disease activity (MRI May 2013, Figure 1a). Nevertheless, due to four documented episodes of lymphopenia with a minimum lymphocyte count of 70 per µl in October 2013 (range 70–370 per µl), therapy was withdrawn in December 2013 and switched to dimethyl fumarate (DMF) 2 × 120 mg in February 2014. The patient was admitted to our hospital 2 months later with paresthesia and worsening of the paresis of the right leg (EDSS 5.0). White blood cell counts showed 6500 per µl leukocytes with 1180 per µl lymphocytes (18.9%). MRI (March 2014) revealed new contrast enhancing lesions right parietal (2.3 cm × 2.2 cm × 2.9cm), left paraventricular and in the pontine area (Figure 1). Investigation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for JC virus copies was negative. Intravenous (i.v.) methylprednisolone treatment (1000 mg for 5 days) combined with two intrathecal triamcinolone injections (2 × 60mg) led to a marked improvement of clinical symptoms (EDSS 4.5 in June 2014, EDSS 4.0 in September 2014) and MRI findings (Figure 1c, f, i: April 2014 and September 2014). DMF treatment was continued.

Figure 1.

Baseline and follow-up MRI of patient 1: axial FLAIR (A–D) depicts a new TDL in the right parietal region (arrow, B, C, D) with peripheral contrast enhancement on the corresponding T1-weighted images (arrow, F, G) compared with the baseline MRI (A, E, I). Additionally, several contrast enhancing lesions (not shown) could be identified in the left paraventricular region, in the left frontal region and in the right pontine region.

FLAIR, fluid attenuation inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TDL, tumefactive demyelinating lesion.

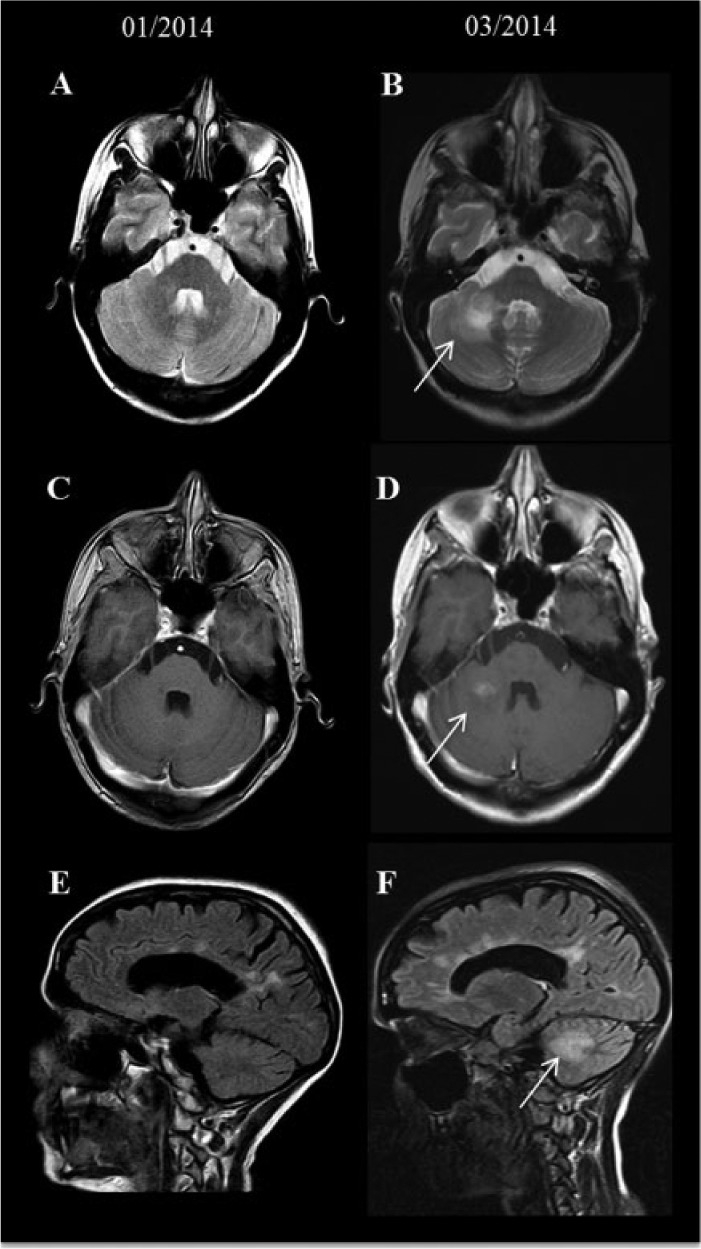

The second patient was a 36-year-old female with a disease course of 13 years. She had not been relapse free during treatment with subcutaneous (s.c.) IFN-β (IFN-β1b s.c. 250 µg every second day; IFN-β1a s.c. 3 × 22µg and 44µg) and glatiramer acetate therapy; thus Nat was initiated in September 2010. During the following 2 years (24 Nat infusions, September 2010 to September 2012), she had been free of RRMS disease activity. Due to a severe bronchitis (September 2012), classified as possible adverse event of Nat, the medication was withdrawn. After a therapy-free interval of 6 months, FTY was started in March 2013. No relapses occurred during FTY therapy. On 23 December 2013, she was admitted to hospital because of angina pectoris and FTY was stopped immediately. DMF 2 × 120 mg was started 7 weeks later; 1 week later she developed a cognitive decline, ataxia, disturbed balance and difficulties with writing and coordination. Cranial MRI performed at the beginning of March 2014 showed multiple contrast enhancing lesions, one of them in the right cerebellum involving the middle cerebellar peduncle (Figure 2 a, c, e). At this time point the lymphocyte count was 1392 per µl (18.3%, 7610 leucocytes per µl). She was treated with i.v. methylprednisolone (1000 mg, 3 days), leading to complete remission.

Figure 2.

Serial MRI of patient 2. Compared with the baseline MRI (A, C and E), axial T2 weighted image and sagittal FLAIR revealed a new TDL in the right cerebellum close to the middle cerebellar peduncle (B, F) with homogenous contrast enhancement on the corresponding T1-weighted images (D).

FLAIR, fluid attenuation inversion recovery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TDL, tumefactive demyelinating lesion.

Discussion

As previously described in Nat patients [Jander et al. 2012], switching from a potent and effective treatment regimen might cause a severe MS rebound after FTY withdrawal. The release of lymphocytes after withdrawal of FTY with rapid influx of lymphocytes into the CSF and reconstitution of the immune system has been discussed as reason for MS rebound [Havla et al. 2012]. Additionally, whereas B cells in the periphery are strongly reduced they are untouched in the CSF upon treatment with FTY [Kowarik et al. 2011]. Furthermore, in patients suffering from rebounds after switching therapy differential diagnoses such as neuromyelitis optica (NMO) or NMO spectrum have to be discussed. Up to now there have been no predictive factors defining this risk group. Of note, in both cases patients were on DMF during the diagnosis of TDLs; however, assumptions concerning the efficacy of fumarates in these cases are difficult objectify about as one patient was on treatment for only 1 week. Nevertheless, the treatment did not seem to be strong and fast enough to maintain disease stability. Experience with fumarates is still scarce and thus the possibility that TDLs developed due to this treatment regimen or that it favored the development of TDLs cannot be discarded.

TDLs are challenging as no specific treatment guidelines exist [Siffrin et al. 2014]. Comparing these two patients with cases mentioned in PubMed articles demonstrates that three patients had TDLs whereas seven had a ‘nontumefactive’ rebound (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with TDLs were stable under FTY (Table 1). Unfortunately, low patient numbers prohibit statistical analyses. The generally low number of patients with MS rebound after FTY withdrawal demonstrates that MS rebounds seem to be a rare but relevant effect of FTY withdrawal and patients should be informed about this potential effect after withdrawal. However, this study cannot present data concerning the frequency of the development of TDLs after FTY withdrawal. Annual 100 relapse rate (ARR) might negatively correlate with relapse severity [TDLs 0, standard deviation (SD) 0 versus nontumefactive 0.28, SD 0.36]. In patients with TDLs the rebounds occurred after 14.6 (SD 11.5) weeks post-cessation of FTY therapy versus 11.7 (SD 3.4). Thus, it has to be stated that 70% of the patients with rebound after FTY withdrawal were free of clinical and radiological disease activity during FTY therapy and the reasons for FTY withdrawal were side effects in 60%.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients with nontumefactive and tumefactive TDLs.

| Variable | Nontumefactive (n = 7) | Tumefactive (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 6/7 (85%) | 2/3 (66%) |

| Age | 34.5 (SD 9.5) | 36.3 (SD 7.5) |

| Age at MS onset | 24.3 (SD 8.3) | 27.6 (SD 8.9) |

| Age MS diagnosis | 24.0 (SD 9.5) | 27.6 (SD 8.9) |

| Duration of FTY treatment (months) | 29.2 (SD 30.5) | 21.5 (SD 17.8) |

| Stable under FTY | 4/7 (57%) | 3/3 (100%) |

| EDSS end FTY | 3.2 (SD 2.4) | 3.5 (SD 0.7) |

| EDSS rebound | 4.9 (SD 1.4) | 4.5 (SD 0.7) |

| EDSS end rebound | 4.1 (SD 1.8) | 4.2 (SD 0.3) |

| Number of MS treatments | 1.5 (SD 0.5) | 1.6 (SD 2.0) |

| ARR FTY | 0.28 (SD 0.36) | 0 (SD 0) |

| Time to rebound after FTY (weeks) | 11.7 (SD 3.4) | 14.6 (SD 11.5) |

| Rebound under immune therapy (IT)? | 0/7 (0%) | 3/3 (100%) |

| If yes, weeks post FTY | – | 11.6 (SD 7.2) |

| Which IT? | – | IFN-β 1a 44 µg, DMF, DMF |

| TDLs? | 0/7 (0%) | 3/3 (100%) |

| Gadolinium enhancement? | 21.6 (SD 2.5) | 1.5 (SD 0.7) |

ARR, annualized relapse rate; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; FTY, fingolimod; MS, multiple sclerosis; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic details of all patients.

| PubMed ID | Sex | Age (years) | Age at onset | Age at MS diagnosis | Duration of FTY therapy (months) | EDSS end FTY | EDSS re-bound | EDSS end rebound | Number of previous MS therapies | FTY stable (1 = yes, 0 = no) | Reason for withdrawal | Consi-dered as side effect? (1 = yes, 0 = no) | ARR FTY | Rebound after FTY with-drawal (weeks) | MS therapy during rebound? (1 = yes, 0 = no) | If MS therapy, weeks post FTY | If MS therapy, which treat-ment? | Tume-factive lesion (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22332194 | m | 45 | 35 | 35 | 48 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1 (IFN-β1a) | 1 | malignant melanoma | 1 | 0.8 | 12 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 23645219 | f | 19 | 11 | 11 | 5 | 3.5 | na | 3 | 1 | 0 | lack of efficacy | 0 | na | 7 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 23829238 | f | 31 | 24 | 24 | 14 | 0 | 3.5 | na | 2 | 1 | wish to become pregnant | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 22829326 | f | 33.5 | 30.9 | na | 30 | 2 | 4 | 3 | na | 1 | suspected infection of CNS (was excluded) | 0 | 0.4 | 12 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 23035074 | m | 29 | 22 | 22 | 42 | na | na | na | 0 | 1 | Herpes zoster infection | 1 | na | 28 | 1 | 20 | IFN-b 1a 44 µg | 1 |

| 24756193 | f | 36 | 19 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 6.5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | lymphopenia | 1 | 0 | 16 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 23161460 | f | 47 | 30 | 35 | 89 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 2 (IFN-β, glatiramer acetate) | 0 | lack of efficacy | 0 | na | 16 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| 23161460 | f | 30 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 1.5 | 4 | 2.5 | 2 (glatiramer acetate, IFN-β) | 0 | genital human papilloma virus infection | 1 | na | 8 | 0 | none | none | 0 |

| Patient 1 | f | 44 | 38 | 38 | 13 | 4 | 5 | 4.5 | 1 (IFN-β1a) | 1 | lymphopenia | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 8 | DMF | 1 |

| Patient 2 | f | 36 | 23 | 23 | 9.5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 (IFN-β1b s.c. 250 µg, IFN-β1a s.c. 3 × 22 µg and 44 µg, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab) | 1 | angina pectoris | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 7 | DMF | 1 |

ARR, annualized relapse rate; DMF, dimethyl fumarate; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; FTY, fingolimod; IFN, interferon; MS, multiple sclerosis; na, not available; s.c. subcutaneous.

Therefore, a beneficial therapeutic response to FTY therapy might be a predisposing factor for severe MS rebound after withdrawal, due to a return of previous high disease activity. Consequently, especially in this patient population with beneficial FTY therapy response and intolerable side effects, switching to an alternative immunotherapy should be performed carefully. Sometimes dosing of patients every other day might be a treatment option. Thus, the need for a therapy-free interval should be critically weighed against the risk of an MS rebound.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosures: S. Faissner received travel grants from Biogen Idec and Genzyme.

R. Hoepner received research and travel grants from Biogen Idec and travel grants from Novartis. C. Lukas received consulting and speaker’s honoraria from Biogen Idec, Bayer Schering, Novartis, Sanofi and received research scientific grant support from Bayer Schering, TEVA and MerckSerono.

A. Chan received personal compensation as a speaker or consultant forBayer Schering, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis and TevaNeuroscience. A. Chan received research support from the German Ministryfor Education and Research (BMBF, German Competence Network MultipleSclerosis (KKNMS), CONTROL MS, 01GI0914), Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec,Merck Serono and Novartis.

R. Gold serves on scientific advisory boards for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Biogen Idec, Bayer Schering Pharma, and Novartis; has received speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Bayer Schering Pharma, and Novartis; serves as editor for Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Diseases and on the editorial boards of Experimental Neurology and the Journal of Neuroimmunology; and receives research support from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Biogen Idec, Bayer Schering Pharma, Genzyme, Merck Serono, and Novartis.

G. Ellrichmann received speakers, travel grants or scientific grant support from BiogenIdec, TEVA Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. and Novartis Pharma.

Contributor Information

Simon Faissner, Department of Neurology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum,Gudrunstr. 56, 44791 Bochum, Germany.

Robert Hoepner, Department of Neurology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

Carsten Lukas, Department of Radiology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

Andrew Chan, Department of Neurology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

Ralf Gold, Department of Neurology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

Gisa Ellrichmann, Department of Neurology, St Josef-Hospital, Ruhr-University Bochum, Bochum, Germany.

References

- Calabresi P., Radue E., Goodin D., Jeffery D., Rammohan K., Reder A., et al. (2014) Safety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (Freedoms II): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol 13: 545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastgir J., Dimario F., Jr. (2009) Acute tumefactive demyelinating lesions in a pediatric patient with known diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: review of the literature and treatment proposal. J Child Neurol 24: 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T., Chang L., Walot I., Huff K. (1998) Physiologic MRI of a tumefactive multiple sclerosis lesion. Neurology 51: 1486–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havla J., Pellkofer H., Meinl I., Gerdes L., Hohlfeld R., Kumpfel T. (2012) Rebound of Disease activity after withdrawal of Fingolimod (FTY720) treatment. Arch Neurol 69: 262–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander S., Turowski B., Kieseier B., Hartung H. (2012) Emerging tumefactive multiple sclerosis after switching therapy from natalizumab to Fingolimod. Mult Scler 18: 1650–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik M., Pellkofer H., Cepok S., Korn T., Kumpfel T., Buck D., et al. (2011) Differential effects of Fingolimod (FTY720) on immune cells in the CSF and blood of patients with MS. Neurology 76: 1214–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C., Gavrilova R., Metz I., Parisi J., Scheithauer B., Weigand S., et al. (2008) Clinical and radiographic spectrum of pathologically confirmed tumefactive multiple sclerosis. Brain 131: 1759–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siffrin V., Muller-Forell W., Von Pein H., Zipp F. (2014) How to treat tumefactive demyelinating disease? Mult Scler 20: 631–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen P., Koch-Henriksen N., Petersen T., Ravnborg M., Oturai A., Sellebjerg F. (2014) Recurrence or rebound of clinical relapses after discontinuation of natalizumab therapy in highly active MS patients. J Neurol 261: 1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]