Abstract

Objective:

Negative symptoms are a significant barrier to successful functional outcome and recovery in individuals with schizophrenia and their management is not unproblematic. Reboxetine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI). Previous studies regarding the useful effects of reboxetine on deficit symptoms of schizophrenia have resulted in inconsistent results. The present study therefore evaluated the effectiveness of reboxetine as an adjunctive treatment in a group of schizophrenic patients with prominent negative symptoms.

Method:

A total of 50 male inpatients meeting diagnosis of schizophrenia entered into a 12-week parallel group, double-blind study for random assignment to reboxetine (n = 25 patients) or placebo (n = 25 patients). The inclusion criterion, in addition to the diagnosis of schizophrenia, was the existence of obvious negative symptoms for a duration of at least 2 years. The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) was used as the primary outcome measure. The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), Simpson Angus Scale (SAS), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) were used for comparison of the intervening parameters in this study.

Results:

According to the findings, 76% of patients in the target group showed some positive response to reboxetine compared with 24% in the control group (p < 0.01). The mean total score of SANS in the reboxetine group decreased significantly from 79.94 ± 1.20 to 74.23 ± 4.07 (p < 0.0001) at the end of the study; such an improvement was not significant in the placebo group with a decrease from 80.42 ± 2.46 to 79.08 ± 5.83 (p < 0.29). Changes of SAPS were insignificant in both groups. Effect size analysis for changes of SANS at the end of assessment indicated a large improvement with reboxetine (Cohen’s d = 2.91).

Conclusion:

Reboxetine, as an adjuvant to haloperidol, may have a helpful effect on the deficit syndrome of schizophrenia.

Keywords: deficit syndrome, negative symptoms, noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors, reboxetine, schizophrenia

Introduction

Negative symptoms are a significant barrier to successful functional outcome and recovery in individuals with schizophrenia [Strauss and Gold, 2012; Strauss et al. 2010]. They also represent a primary unmet need in schizophrenia therapeutics, as no drug has received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for an indication of negative symptoms. Although the importance of studying negative symptoms may be clear, ideas regarding which aspects of psychopathology should be considered part of the negative symptom construct have changed over the years. Symptom rating scales developed in the 1980s regarded such clinical features as poverty of content of speech, inappropriate affect and attention to be negative symptoms [Andreasen, 1982]. However, factor analytical studies show that these symptoms are more closely tied to other aspects of pathology (e.g. disorganization) than negative symptoms [Buchanan and Carpenter, 1994]. But while negative symptoms are not infrequent in schizophrenia, their management is not unproblematic. For example, antidepressants have had contradictory results, so far, as potential therapeutic agents in negative symptoms of schizophrenia, with positive outcomes such as with escitalopram and nortriptyline [Shoja Shafti, 2006, 2007] or, conversely, negative conclusions such as with fluoxetine and maprotiline [Carpenter, 1997].

Reboxetine is an antidepressant drug used in the treatment of clinical depression, panic disorder and attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD) and is predominantly metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme. Reboxetine can also produce relatively rapid improvement in symptoms of social phobia. Social impairments, particularly those revolving around negative self-perception and a low level of social activity, appear to respond positively to reboxetine [Taylor et al. 2012]. Reboxetine essentially acts as a pure norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI) with very little activity on the serotonin transporter and without direct effects on the dopaminergic neurotransmission [Baldessarini, 2010] and hence is a somewhat well-tolerated, fairly selective ‘noradrenergic’ agent. NRIs may be especially useful in drive-deficient ‘anergic’ states where the capacity for sustained motivation is lacking and also in the treatment of retarded and melancholic depressive states with a reduced capability to deal with stress [Weiss et al. 2003]. Previous studies regarding potential useful effects of reboxetine on deficit syndrome of schizophrenia have resulted in contradictory results [Raedler et al. 2004; Schutz and Berk, 2001; Kishi et al. 2013]. In the present study, the effectiveness of reboxetine as an adjunctive treatment in a group of schizophrenic patients with prominent negative symptoms has once more been evaluated.

Method

A total of 50 male inpatients meeting the diagnosis of schizophrenia, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision [APA, 2000], were entered into a 12-week parallel group, double-blind study for random assignment to reboxetine (n = 25 patients) or placebo (n = 25 patients). Since the field of research was restricted to the chronic male section of the psychiatric hospital, all the samples were selected from among chronic male schizophrenic patients. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from either the participant or a legal guardian or representative. In addition, the whole procedure was approved by the related ethical committee of the university.

The inclusion criterion, in addition to the diagnosis of schizophrenia, was the existence of obvious negative symptoms for a duration of at least 2 years. Cases with comorbidities such as major depressive disorder, mental retardation, neurological disorders, medical complications, severe aggressiveness, medical deafness or muteness were excluded from the study. In addition, cases with diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or cases that had been prescribed a long-acting depot (during the last 6 months) or atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants or lithium were excluded (diagram 1).

Diagram 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) was used as the primary outcome measure in this experiment for assessment of negative symptoms [Andreasen, 1981]. In addition the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Andreasen, 1984], Simpson Angus Scale (SAS) [Simpson and Angus, 1970], Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) [Folstein et al. 1975] and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [Hamilton, 1960] were used for comparison of the intervening parameters in this study. High negative symptom scores (>55% of total SANS, ⩾66), low positive symptoms scores (<55% of total SAPS, ⩾96), and low extrapyramidal symptom scores (<25% of total SAS, ⩽10) were the basis of our inclusion criteria. To exclude depression and cognitive disturbances that could be confused with negative symptoms, HAM-D and MMSE were used, respectively. HAM-D >10 and MMSE <25 were identified as likely depression and cognitive disturbance, and could lead to patient exclusion.

All patients, after a washout period of 2 weeks, were prescribed haloperidol (5 mg/day), and after that randomized to either the placebo or reboxetine (4 mg/day) group. Since higher doses of reboxetine, like other antidepressants, could increase the hazard of intensification of psychosis, and the aim of the present assessment was evaluating the effectiveness of that drug on merely the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, so the lower dosage was selected. The tablets were prescribed while previously inserted into empty and similar capsules, which were prepared in this regard, to make patients blind regarding the procedure. The evaluator (a psychiatrist) also remained unaware concerning the abovementioned panel and the type of medications prescribed for each group. All of the patients remained hospitalized throughout the experiment. The duration of the assessment was 12 weeks, and the patients were assessed at baseline (week 0), and at the end of 4th, 8th and 12th weeks by SANS and SAPS.

Statistical analysis

Patients were compared on baseline characteristics using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Treatment efficacy was analyzed by t-test and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing both groups over 12 weeks. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided p value ⩽0.05. Cohen’s standard (d) and correlation measures of effect size (r) were used for comparing baseline to endpoint changes in primary outcome measure. Response was defined as a reduction of ⩾20% in the severity of SANS score (total and/or subscales). MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.2 was used as the statistical software tool for the analysis.

Results

Analysis for efficacy was based on data from an equal number of patients (n = 25) in both groups because there was no dropout during the assessment. Since all of the patients were hospitalized during the study, and moreover due to lack of serious adverse effects and short duration of experiment, there was no premature discontinuation in none of the aforesaid groups. Groups were originally analogous with respect to comparable demographic and diagnostic variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in control and target groups.

| Variables | Placebo | Reboxetine | χ2 | t | df | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of schizophrenic patients | n = 25 | n = 25 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.88 | ||

| Age (years old) | 4.21 ± 39.84 | 1.17 ± –41.0 | 1.36 | 48 | 0.17 | −0.56 to 2.94 | |

| Duration of illness(years) | 1.28 ± 8.69 | 0.37 ± 9.01 | 1.20 | 48 | 0.23 | −0.21 to 0.85 | |

| Number of married patients | n = 18 | n = 15 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.72 | ||

| Number of prior episodes: mean ± standard deviation | 9.29 ± 2.14 | 8.93 ± 1.72 | 0.65 | 48 | 0.51 | −1.46 to 0.74 | |

| MMSE | 27.41 ± 1.38 | 26.68 ± 1.59 | 1.73 | 48 | 0.08 | −1.57 to 0.11 | |

| HAM-D | 5.36 ±1.83 | 1.69 ± 6.02 | 1.32 | 48 | 0.19 | −0.34 to 1.66 | |

| Baseline SANS | 80.42 ± 2.46 | 79.94 ± 1.20 | 0.87 | 48 | 0.38 | −0.62 to 1.58 | |

| Baseline SAPS | 85.27 ± 6.13 | 86.36 ± 7.15 | 0.57 | 48 | 0.56 | −4.78 to 2.69 |

HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms.

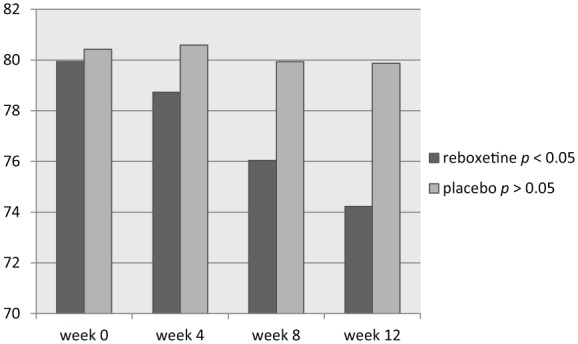

According to the findings and based on the changes of SANS, 76% of patients in the target group showed some positive response to reboxetine compared with 24% in the control group (χ2 = 5.76, df = 1, p < 0.01) (Table 2). In this regard, the mean total score of SANS in the reboxetine group decreased significantly from 79.94 ± 1.20 to 74.23 ± 4.07 (95% CI: 4.04–7.41, df = 48, t = 6.72, p < 0.0001) at the end of the study; such an improvement was not significant in the placebo group with a decrease from 80.42 ± 2.46 to 79.08 ± 5.83 (95% CI: –3.88 to 1.20, df = 48, t = 1.059, p = 0.29); see Table 3 and Figure 1. In addition, between-group analysis showed that the mean total score of SANS in the reboxetine group, compared with the control group, improved significantly at the 8th and 12th weeks (p < 0.03 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Table 4). Repeated-measures ANOVA, regarding the mean SANS total score, showed significant improvement in the reboxetine group [F(3,72) = 3.25; p < 0.02; sum of squares (SS) = 591.95; mean squared error (MSE) = 60.66], and nonsignificant change in the control group [F(3,72) = 0.231; p < 0.87; SS = 35.74; MSE = 51.54]. Split-plot (mixed) design ANOVA also showed significant difference in this regard [F(3,96) = 4.11; p < 0.001; SS = 6.71; MSE = 32.98].

Table 2.

Number of patients with positive response ( ⩾20% decrease in total and subtests of SANS) in both groups.

| Negative symptoms | Placebo (%) | Reboxetine (%) | χ2 | df | p value | Contingency coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | 1 (4%) | 8 (32%) | 4.00 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.555 |

| ALOGIA | 3 (12%) | 12 (48%) | 4.26 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.471 |

| AA | 2 (8%) | 10 (40%) | 4.08 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.504 |

| An As | 1 (4%) | 9 (32%) | 4.90 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.573 |

| AD | 2 (8%) | 11 (44%) | 4.92 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.524 |

| Total | 6 (24%) | 19 (76%) | 5.76 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.433 |

AA, avolition–apathy; An As, anhedonia–asociality; AB, affecting blunting; AD, attention deficit; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms.

Table 3.

Intragroup analysis of SANS and SAPS between baseline (week 0) and week 12.

| Measures\weeks | Baseline | Week 12 | % change | t | df | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SANS-reboxetine | 79.94 ± 1.20 | 74.23 ± 4.07 | −7.14 | 6.72 | 48 | 0.0001 | 4.04 to 7.41 |

| SANS–placebo | 80.42 ± 2.46 | 79.08 ± 5.83 | −1.66 | 1.05 | 48 | 0.29 | −3.88 to 1.20 |

| SAPS–reboxetine | 86.36 ± 7.15 | 88.69 ± 7.41 | +2.62 | 1.13 | 48 | 0.26 | −1.81 to 6.47 |

| SAPS–placebo | 85.27 ± 6.13 | 85.31 ± 7.59 | +0.04 | 0.02 | 48 | 0.98 | −3.88 to 3.96 |

CI, confidence interval; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms.

Figure 1.

Changes of SANS between baseline (week 0) and week 12.

SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms.

Table 4.

Between-group analysis of SANS and SAPS at baseline (week 0) and weeks 4, 8 and 12.

| Drugmeasure | Reboxetine | % change | Placebo | % change | t | df | p | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SANS–Baseline | 79.94 ± 1.20 | 0 | 80.42 ± 2.46 | 0 | 0.87 | 48 | 0.38 | −0.62 to 1.58 |

| SANS–4th week | 78.73 ± 5.62 | −0.26 | 80.59 ± 4.81 | +0.21 | 1.25 | 48 | 0.21 | −1.11 to 4.83 |

| SANS–8th week | 76.04 ± 6.84 | −4.87 | 79.93 ± 5.93 | −0.60 | 2.14 | 48 | 0.03 | 0.25 to 7.53 |

| SANS–12th week | 74.23 ± 4.07 | −7.14 | 79.87 ± 5.83 | −1.66 | 2.63 | 48 | 0.01 | 0.88 to 6.59 |

| SAPS–Baseline | 86.36 ± 7.15 | 0 | 85.27 ± 6.13 | 0 | 0.57 | 48 | 0.56 | −4.78 to 2.69 |

| SAPS–4th week | 86.79 ± 6.23 | +0.46 | 85.46 ± 5.82 | +0.22 | 0.78 | 48 | 0.43 | −4.75 to 2.09 |

| SAPS–8th week | 87.61 ± 4.69 | +1.42 | 85.19 ± 4.58 | −0.09 | 1.84 | 48 | 0.07 | −5.05 to 0.21 |

| SAPS–12th week | 88.69 ± 7.41 | +2.62 | 85.31 ± 7.59 | +0.04 | 1.59 | 48 | 0.11 | −7.64 to 088 |

CI, confidence interval; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms, SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms.

Also regarding the mean SAPS total scores, repeated-measures ANOVA showed nonsignificant alterations in the reboxetine and control groups [F(3,72) = 0.853; p < 0.46; SS = 76.85; MSE = 30.04; and F(3,72) = 0.009; p < 0.99; SS = 0.83; MSE = 31.00, respectively] (Figure 2). In addition, split-plot (mixed) design ANOVA did not show any significant difference in this regard [F(3,96) = 0.397; p < 0.75; SS = 35.56; MSE = 29.88].

Figure 2.

Changes of SAPS between baseline (week 0) and week 12.

SAPS, Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms.

According to the results, all of the subscales of SANS demonstrated significant improvement in the reboxetine group compared with the placebo group (Table 2).

During the present study, no significant shifting in the positive symptoms was discernible. It should be pointed out, however, that by means of this minor dosage of reboxetine, the mean SAPS total score showed an insignificant escalation (86.36 ± 7.15 to 88.69 ± 7.41) in the target group (95% CI: –1.81 to 6.47; df = 48; t = 1.131, p < 0.26). A total of 48% (n = 12) of patients in the placebo group and 40% (n = 10) in the reboxetine group required an anticholinergic drug for remission of tremor or Parkinsonism at some stage in the study (χ2 = 0.081; df = 1; p < 0.77). Since the sample size was small, the effect size was analyzed for changes in SANS at the end of assessment, which showed a large (d ⩾ 0.8), improvement with reboxetine (Cohen’s d = 2.91, effect size r = 0.82). Post hoc analysis showed power = 0.53 (intermediary) on behalf of this trial, which turned to power = 0.81 in compromise power analysis. A total of 9 patients in the reboxetine group (36%) experienced some mild to moderate side effects such as headache, insomnia, constipation and dry mouth but none of them led to any major problem or withdrawal from the experiment.

Discussion

Negative symptoms have long been recognized as an integral and clinically important part of schizophrenia. However, the concept has changed over time from Kraepelin’s early description of the destruction of the personality [Kraepelin, 1971], through the domains concept of Strauss and colleagues [Strauss et al. 1974] and Crow’s concept of type II schizophrenia [Crow, 1985] to the operationalization of negative symptoms in SANS, the Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale (PANSS), the Negative Symptom Assessment and others [Andreasen, 1989; Kay et al. 1987].

According to the findings of the present study, reboxetine, as an adjuvant drug, caused significant improvement in the negative symptoms, while causing no important increase in the positive symptoms. As is known, reboxetine is helpful in the treatment of depression [Taylor et al. 2012; Baldessarini, 2010]. It also reduces olanzapine-associated weight gain through activation of the adrenergic system [Poyurovsky et al. 2003]. Maybe, the dopamine-blocking properties of antipsychotic drugs have a negative effect on mood and drive and, in addition, treatment with typical antipsychotics has been occasionally associated with emergence of depression in schizophrenic patients [Carpenter, 1997]. There is some evidence that noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NARIs) may enhance central serotonin function by a mechanism that is independent from reuptake inhibition. An association between negative symptoms and dysregulation of serotonin system is suggested by an abnormal prolactin response to fenfluramine in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder [Carpenter, 1997]. However, reboxetine also has a modulating effect on the dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area and may cause a selective increase in the dopamine availability in the prefrontal cortex. Thus it may possibly help to undo a number of challenging side effects of antipsychotics on mood and drive [Poyurovsky et al. 2003]. In a comparative study, reboxetine was considerably better than paroxetine and placebo regarding improvement of attention and enhancement of cognitive function in patients suffering from major depressive disorder [Raedler et al. 2004], an outcome that persuaded others to undertake a comparable survey respecting schizophrenic patients. However, Schutz and Berk in a 6-week randomized controlled trial on 30 schizophrenic patients found no significant difference between reboxetine and placebo on the topic of improvement of deficit syndrome [Schutz and Berk, 2001].

In addition, Kishi and colleagues in a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials comparing NRI augmentation therapy (including atomoxetine, reboxetine, reboxetine–betahistine combination and mazindol) with placebo in patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics found no statistically significant effects of NRI augmentation therapy on overall, positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. NRI augmentation therapy was marginally superior to placebo for efficacy of depressive symptoms, and dropout due to all-cause, inefficacy or adverse events was similar in both groups. While NRI augmentation therapy, in general, showed a significantly lower increase or larger reduction in body weight than placebo, reboxetine augmentation was associated with less weight gain than placebo in antipsychotic treated schizophrenia patients [Kishi et al. 2013].

In contrast, Raedler and colleagues found, in an open-label trial seeking the effectiveness and tolerability of the adjunctive reboxetine in a group of schizophrenic patients with prominent negative symptoms, that all clinical scores improved significantly as a result of adjunctive treatment with reboxetine [Raedler et al. 2004]. In addition, all the patients tolerated treatment without any major adverse effects.

Hence, the results of the present assessment are in agreement with the findings of Raedler and colleagues and not in accord with the conclusions of Schutz and colleagues and Kishi and colleagues, except on the subject of the safety of reboxetine. However, the short duration of the present assessment and minor dose of reboxetine may have prevented a better efficiency of reboxetine. Besides, whether adding reboxetine to atypical antipsychotics could result in the same outcome or not, requires another evaluation.

Although these results are investigative and need to be confirmed by further analogous studies, they were encouraging because they have illustrated significant amelioration of negative symptoms in a group of schizophrenic patients. Small sample size and short duration of trial were among the major limitations of this assessment. Well-powered, prospective, randomized placebo-controlled trials using the MATRICS battery concomitantly with functional outcome measures are necessary to elucidate reboxetine’s efficacy as an adjunctive treatment for negative symptoms.

Conclusion

Reboxetine, as an adjuvant to haloperidol, may have helpful effects on the deficit syndrome of schizophrenia.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge their colleagues, S. Akbari, MD, P. Sadeghi, MS, and the department of research for their practical and financial support of this study.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Saeed Shoja Shafti, Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Razi Psychiatric Hospital, PO Box 18735-569, Tehran, Iran.

Mohammad Sadeghe Jafarabad, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Reza Azizi, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Andreasen N. (1981) The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1982) Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: definition and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39: 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1984) The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA: Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1989) The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 7: 49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini R. (2010) Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders: depression and anxiety disorders. In: Hardman J., Limbird L., Goodman Gilman A. (eds), Goodman & Gilman’s Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 10th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 447. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R., Carpenter W. (1994) Domains of psychopathology: an approach to the reduction of heterogeneity in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 182: 193–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter W. (1997) Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: negative symptoms. Am J Psychiatr 154: 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Crow T. (1985) The two-syndrome concept: origins and current status. Schizophr Bull 11: 471–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M., Folstien S., McHugh P. (1975) Mini- mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960) Rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S., Fiszbein A., Opler L. (1987) The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13: 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T., Mukai T., Matsuda Y., Moriwaki M., Iwata N. (2013) Efficacy and safety of noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor augmentation therapy for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res 47: 1557–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. (1971) Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia [translated by Barclay R.M.]. Huntington, NY: Robert E. Krieger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Poyurovsky M., Isaacs I., Fuchs C., Schneidman M., Faragian S., Weizman R., et al. (2003) Attenuation of olanzapine-induced weight gain with reboxetine in patients with schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatr 160: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raedler T., Jahn H., Arlt J., Kiefer F., Schick M., Naber D., et al. (2004) Adjunctive use of reboxetine in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 19: 366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz G., Berk M. (2001) Reboxetine add on therapy to haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a preliminary double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 275–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoja Shafti S. (2006) Treatment-responsiveness of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a double-blind placebo-control clinical trial. Iranian J Med Sci 31: 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Shoja Shafti S. (2007) Amelioration of negative symptoms in schizophrenia by escitalopram: a double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Schizophrenia Related Psychosis 1: 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G., Angus J. (1970) A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatry Scand 212: 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G., Gold J. (2012) A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 169: 364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J., Carpenter W., Bartko J. (1974) The diagnosis and understanding of schizophrenia. Part III. Speculations on the processes that underlie schizophrenic symptoms and signs. Schizophr Bull 11: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G., Harrow M., Grossman L., Rosen C. (2010) Periods of recovery in deficit syndrome schizophrenia: a 20-year multifollowup longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull 36: 788–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D., Paton C., Kapur S. (2012) The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry, 11th edn. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J., Dormann S., Facklam M., Kerpen C., Ketabi N., Haefeli W. (2003) Inhibition of P-glycoprotein by newer antidepressants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 305: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]