Abstract

Aim:

This study evaluated adherence to treatment, quality of life and subjective well-being in patients with psychosis treated with long-acting injectable risperidone. Subjects enrolled were part of a larger study where patients were observed in an adherence to treatment program of the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Materials and methods:

A total of 27 nonadherent patients (21 men, six women; mean age: 36.1 years; range: 23–63 years) were enrolled. Maximum observational period was 30 months.

Results:

A total of 12 patients were under treatment for 30 months (44.44%) but only nine had a valid 30-month follow up, while the remaining three patients initially treated at our unit continued long-acting risperidone at their local centre. Reductions of monthly mean values of Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA): p < 0.0001] and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (p < 0.0001), increase of monthly mean values of Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale (SWN) (p < 0.0001) and Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (S-QoL) (p < 0.01) were observed. Significant differences with respect to SAPS baseline values from the sixth month, SANS baseline values from the seventh month, SWN baseline values from the eighth month, S-QoL baseline values from the eighteenth month were shown in post hoc tests. Reduction of SAPS mean values was associated with increase of SWN (p < 0.0001) and S-QoL (p < 0.0001) mean values as demonstrated by correlation analysis. The same inverse correlation was found between reduction of SANS mean values and increases of SWN (p < 0.0001) and S-QoL (p = 0.0001) mean values.

Conclusions:

Long-term treatment with long-acting risperidone may be associated with improvement to adherence to therapy and quality of life. Patients may show improvement in psychopathological symptoms, subjective well-being and quality of life.

Keywords: long-acting antipsychotics, nonadherence, quality of life, risperidone, schizophrenia, subjective well-being

Introduction

A high proportion of patients, either psychiatric or not psychiatric, do not fully comply with long-term treatments leading to frequent drop-out episodes [Sendt et al. 2015; Bera, 2014]. Dealing with adherence to a defined pharmacological treatment is crucial in the clinical setting because of direct (such as higher rates of rehospitalization [Kane, 2014]) and indirect consequences (such as higher mortality for all causes [Marder, 2013]).

Patients frequently show a certain level of ‘discontinuity’ during a long-term pharmacological treatment; as a result, in Western countries only one out of two chronically affected patients regularly takes their drugs [World Health Organization, 2003]. Nonadherence is therefore a meaningful challenge among all branches of medicine and psychiatry in particular.

The phenomenon has serious consequences: nonadherence is the main cause of clinical failure and has long-term complications such as increased suicide risk, increased substance abuse, a higher mortality for all causes, a higher rate of rehospitalization and a significant impairment of psychosocial relations and quality of life with greater health costs [Ascher-Svanum et al. 2006].

In particular, previous psychiatric studies [Kane, 2003; Lacro et al. 2002] have shown that nonadherence is a major problem in the treatment of schizophrenia with a prevalence ranging from 20% to 79%. One of the most important issues in long-term treatment of schizophrenia is adherence to antipsychotic drugs with a decreasing compliance; a review of the English literature reported compliance rates of 60–85% in schizophrenics during the first month of treatment, with only 50% at 6 months [Llorca, 2008].

Several studies [Schennach et al. 2012; Caseiro et al. 2012] showed that nonadherent patients with schizophrenia present with a high incidence of recurrence, usually worse compared with the first episodes and that take longer to resolve with a higher tendency to rehospitalization and a negative impact on social and working life [Subotnik et al. 2011].

Although adherence is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon related to the type of disease and drugs used, patient attitude to medications seems to be a main factor, with compliance being strongly influenced by patient perception of benefits and costs [Siracusano et al. 1998; Parellada et al. 2005]. It has been demonstrated that in stable patients with schizophrenia, adherence is mainly related to the recognition of the positive effects of the pharmacological therapy on daily life [Keith et al. 2004; Lindenmayer et al. 2005]. In particular, during long-term therapies subjective perception of general wellness and quality of life are clear factors influencing and maintaining adherence to treatment [Gastpar et al. 2005]. Consequently a significant role has been assigned recently to the notion of subjective well-being and quality of life even in patients submitted to antipsychotic medications [Correll, 2011].

Previous research based on both subjective perception and objective measures have already showed that use of long-acting risperidone is associated with a significant improvement in quality of life. One study evaluated the impact of long-acting risperidone on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures by comparing the results of treatment groups with the US general population. After 12 weeks of treatment, HRQoL measures improved, approaching the general population values [Nasrallah et al. 2004].

Also in the StoRMi study [Möller et al. 2005], the main domains of HRQoL were improved significantly; patients showed an overall amelioration of quality of life related to the health status and a significant increase in fields such as mental health, vitality, social activities, and role limitations secondary to emotional status.

Well-known additional factors determining drop out of antipsychotic drugs are: side effects (mainly extra-pyramidal symptoms such as akathisia), complex treatment plans and misunderstanding of dosage schemes [Bay et al. 2006]. Considering that the introduction of atypical antipsychotic drugs partially reduced the incidence of side effects, and moreover the formulation of antipsychotic treatment appears to play an important role, the development of long-acting drugs should further simplify the dosage plans thus reducing mistakes and improving the regular intake of medications.

Several studies have shown a rate of relapse significantly lower with depot medication compared with oral medication [Schooler, 2003; Lambert et al. 2011]. In this setting, long-acting risperidone is a strategy for the treatment of schizophrenia among patients with a history of poor adherence.

It seems clear that long-acting risperidone seems to put together the advantages of atypical antipsychotics with a long-acting formulation [Lasser et al. 2005].

The present study aims to: (1) evaluate adherence to pharmacological treatment in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders submitted to long-acting risperidone; (2) evaluate the impact on quality of life and subjective perception of psychophysical wellness.

Materials and methods

Participants

The present study is part of a larger investigation examining achievable predictors of adherence in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Hence, the original sample was composed of 202 voluntarily hospitalized inpatients, divided as follows: 89 patients (44% of the sample) with bipolar disorder (I and II); 91 patients (45%) with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; and 22 patients (11%) with major depression. From this we extracted the final sample group of 91 patients with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, spontaneously admitted to the hospital and followed up as outpatients at the Operative Unit of Psychiatry of the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Experienced clinical psychiatrists made diagnostic assessments using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-CV) [First et al. 1997].

Their adherence to pharmacological treatment has been evaluated on the basis of the information provided by the patient and family doctor/psychiatrist, and on the basis of the information obtained in the course of direct interviews conceived by our staff: ‘adherence checklist’ and ‘Pharmacological treatment before the Admission’ (Appendices 1 and 2 of the online supplementary material) assessing demographic data, the presence or absence of a caregiver, abuse of illegal substances, the number of years of treatment, the number of hospital admissions, the reason for the interruption of the pharmaceutical treatment, the therapy followed before hospitalization, and the degree of adherence. The degree of adherence was categorized as ‘low’, ‘moderate’, or ‘high’. In order to categorize the degree of adherence, we used the notion of ‘prescribing gap’, that is the proportion of time a patient goes without receiving their intended prescribed medication (>80% good adherence, 60-80% moderate adherence, <60% low adherence). In the course of the interviews, patients were also asked the name and dose of their medications, and their reasons for missing doses.

All patients with doubtful adherence (i.e. ‘moderate’) were included in the nonadherent group. Adherence to treatment was confirmed in 40 patients, with 51 nonadherent patients. Of the latter, 27 were switched to long-acting risperidone.

The final sample group was therefore made up of 27 nonadherent patients (21 men and 6 females) with a mean age of 36.1 years (range, 23–63 years). The maximum observational period was 30 months.

Inclusion criteria

(1) Patients aged 18–65 years; (2) DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; (3) patients responding to antipsychotic pharmacological therapy and, in particular, to oral risperidone; (4) patients with frequent episodes of recurrence with hospital admission because of poor adherence to treatment.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Patients previously treated with oral risperidone showing resistance or side effects; (2) patients under treatment with other depot antipsychotic drugs.

Risperidone administration and dosage

Long-acting risperidone was administered intramuscularly twice a month using 25, 37.5 or 50 mg dosages. Choice of dosage as well as maintenance or suspension of oral antipsychotic therapies were based on clinical status and results of administered efficacy scales.

When starting pharmacological treatment, during the latent period of 3 weeks preceding the release of risperidone from injected microspheres, patients continued to take oral 2–7 mg per day risperidone in order to guarantee a correct antipsychotic coverage. In other cases, previously treated with other first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs (haloperidol, clozapine, olanzapine), patients were switched to oral risperidone.

Assessment of adherence to long-acting risperidone and treatment effectiveness

Patient adherence to treatment was evaluated on the basis of punctuality and accuracy of control visits for the following risperidone administration.

In order to evaluate efficacy of pharmacological therapy on positive and negative symptoms two scales were used: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Andreasen, 1984a] and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [Andreasen, 1984b]. In order to evaluate subjective well-being perception during pharmaceutical treatment with risperidone, the shortened, 20-item, Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale (SWN) was performed. The SWN is a self-report Likert-scale with six response categories covering 10 positive and 10 negative statements on emotional regulation, self-control, mental functioning, social integration, and physical functioning that can be completed in 5–10 minutes [Naber, 1995]. The SWN shows sufficient internal consistency and good construct validity (Cronbach’s α of the total score 0.92, 0.63–0.82 for the subscores).

In addition, the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (S-QoL) [Auquier et al. 2003] was used to examine quality of life. The S-QoL questionnaire was based on the concept of health-related quality of life which is defined as the discrepancies perceived by patients between their expectations and their current life experiences. This self-administered questionnaire consists of 41 items grouped into eight subscales: psychological well-being, self-esteem, family relationships, relationship with friends, resilience, physical well-being, autonomy and sentimental life.

All scales were administered at the baseline (in other words during first long-acting risperidone administration), monthly for the first 12 months and then every 6 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of sample. Data are reported as frequencies, percentage and mean (SD). BL, baseline; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS, Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SWN, Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale; S-QoL, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale.

| Time | Number of patients | Adherence (%) | SAPS | SANS | SWN | S-QoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 27 | 100 | 41.56 (21.80) | 28.52 (21.04) | 101.84 (34.05) | 94.14 (25.90) |

| 1st month | 21 | 77.78 | 38.57 (17.73) | 24.57 (17.98) | 107.73 (31.86) | 100.78 (24.22) |

| 2nd month | 20 | 74.07 | 39.30 (16.06) | 22.05 (17.88) | 113.07 (34.14) | 106.00 (23.09) |

| 3rd month | 17 | 62.96 | 40.71 (16.81) | 22.94 (17.16) | 117.31 (33.81) | 105.29 (24.86) |

| 4th month | 13 | 48.15 | 37.54 (19.02) | 17.38 (9.10) | 113.75 (35.23) | 110.75 (28.90) |

| 5th month | 13 | 48.15 | 36.15 (19.28) | 15.85 (9.56) | 113.83 (34.89) | 114.58 (28.79) |

| 6th month | 10 | 37.04 | 34.70 (16.36) | 13.70 (7.76) | 128.67 (32.50) | 115.10 (23.03) |

| 7th month | 9 | 33.33 | 32.78 (15.70) | 12.11 (7.42) | 130.89 (32.10) | 110.22 (21.41) |

| 8th month | 9 | 33.33 | 32.78 (16.23) | 11.67 (7.55) | 137.78 (31.10) | 107.89 (20.10) |

| 9th month | 9 | 33.33 | 31.78 (15.82) | 11.22 (7.17) | 140.89 (30.69) | 108.44 (20.57) |

| 10th month | 9 | 33.33 | 31.56 (15.92) | 10.11 (6.85) | 140.56 (30.35) | 113.33 (24.65) |

| 11th month | 9 | 33.33 | 31.33 (15.78) | 10.33 (7.26) | 142.00 (30.16) | 109.89 (28.32) |

| 12th month | 9 | 33.33 | 30.44 (15.32) | 9.22 (7.50) | 143.56 (28.88) | 112.78 (28.28) |

| 18th month | 9 | 33.33 | 28.67 (14.81) | 9.22 (7.14) | 144.56 (25.89) | 118.11 (26.27) |

| 24th month | 9 | 33.33 | 27.22 (14.32) | 8.78 (7.14) | 147.44 (25.54) | 120.33 (26.75) |

| 30th month | 9 | 33.33 | 26.56 (14.10) | 8.89 (6.95) | 147.44 (23.14) | 122.00 (27.34) |

The study design was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Committee of the University of Rome Tor Vergata and subjects participated with informed, voluntary, written consent.

Statistics

Four separate models of repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA) were carried out to study time variations of scores during the observational period of 30 months (within subject factor had 16 repetition levels, from the baseline to the 30 month values), in the two psychopathological scales (SANS and SAPS; their decreases from baseline values were considered as an index of efficacy) and in the two subjective perception and quality of life scales (SWN and S-QoL). In order to define which variables contributed to the measured effects, post hoc tests were performed with the Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons.

Finally, Pearson correlation analysis was performed in order to study, during the observational period of 30 months, the association between the monthly mean values variations of clinical scales (SAPS and SANS) and of self-report scales (SWN and S-QoL).

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Of the 27 patients included in the study two patients had to stop pharmacological treatment because of adverse events: the first patient experienced a significant weight increase, agitation, insomnia, and disorganized behaviour; the second had hyperprolactinemia. Four patients had to stop therapy according to physician opinion because of inefficacy between the first and sixth month; one patient interrupted therapy for other reasons. Eight patients were lost at follow up after the first administration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reason for discontinuation by mode dose in patients treated with long-acting risperidone.

| Drop-out motivation |

Dosage |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mg | 37.5 mg | 50 mg | |

| Side effects | 2 | ||

| Lost to follow up | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Inefficacy | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | ||

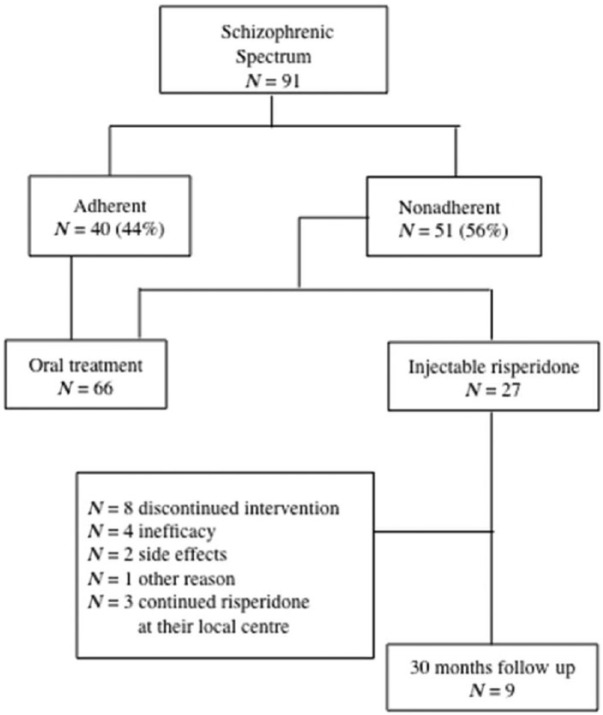

To date, 12 patients have followed the treatment for 30 months (44.44%): nine patients at the Outpatient Center of the Unit of Psychiatry of the University of Rome Tor Vergata (33.33%); three patients, initially treated at our Unit for a period of time between the first and third month, continued their therapy with long-acting risperidone at their local centre and clinical data were not available for the current analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrolment, randomization and follow up of the study patients.

Descriptive analysis showed reduction of SAPS scores from 28.52 at baseline (0–89) to 7.33 (0–13) and reduction of SANS scores from 41.56 at baseline (0–90) to 27.17 (10–48) at 30 months; increase of S-QoL scores from 94.14 at baseline (58–140) to 127.17 (89–169) and increase of SWN scores from 103.72 at baseline (50–156) to 145 (104–166) at 30 months (Table 1).

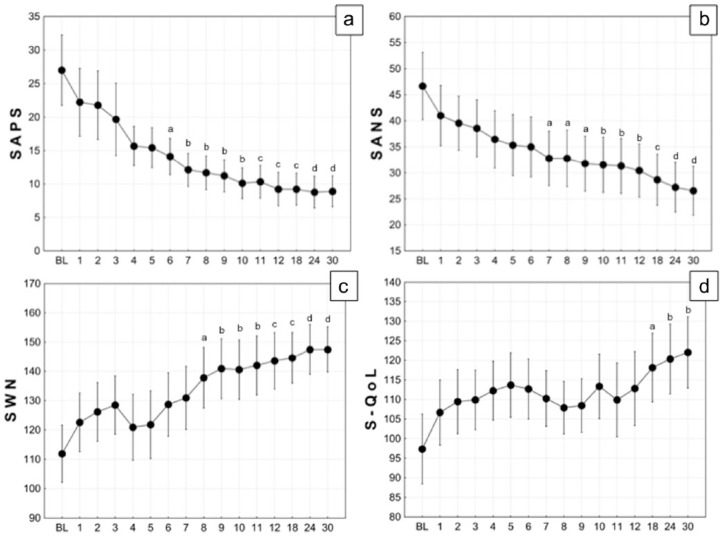

During the 30 months of the study, a significant decrease of the total score of SAPS (rm-ANOVA: F15,120 = 5.418, p < 0.0001, = 0.404) and SANS (F15,120 = 4.307, p < 0.0001, = 0.350) were observed. Post hoc tests showed significant differences with respect to SAPS baseline values from the sixth month (Figure 2a) and significant differences with respect to SANS baseline values from the seventh month (Figure 2b). On the other hand, during the 30 months, a significant increase of the SWN (F15,120 = 5.713, p < 0.0001, = 0.417) and S-QoL (F15,120 = 2.182, p = 0.01, = 0.214) were observed. Post hoc tests showed significant differences with respect to SWN baseline values from the eighth month (Figure 2c) and significant differences with respect to S-QoL baseline values from the eighteenth month (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Temporal course of Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (A), Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SAPS) (B), Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale (SWN) (C) and Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (S-QoL) (D) during 30 months of long-acting risperidone treatment. Black circle are mean; vertical bars are standard error of the mean (SEM). Lowercase letters indicate p-value of Bonferroni post hoc test of a specified temporal condition respect to related baseline condition: a, p < 0.05; b, p < 0.01; c, p < 0.001; d, p < 0.0001.

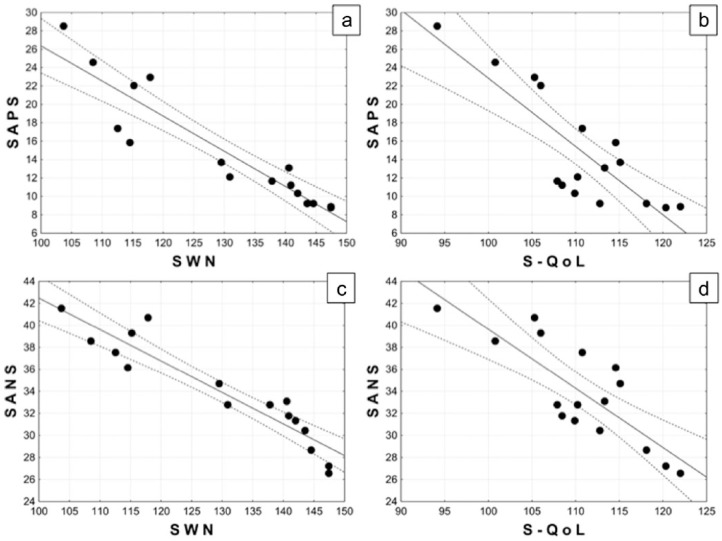

Correlation analysis showed that, during the 30 months, the reduction of mean values of SAPS was strongly associated with an increase of mean values of SWN (r = –0.926, r2=0.858, p < 0.0001; Figure 3a) and S-QoL (r = –0.836, r2=0.700, p < 0.0001; Figure 3b). The same inverse robust correlation was found between the reduction of SANS mean values and the increases of mean values of SWN (r = –0.937, r2=0.878, p < 0.0001; Figure 3c) and S-QoL (r = –0.814, r2=0.670, p=0.0001; Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis between Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) mean values and: Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptic Treatment Scale (SWN) mean values (a), Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (S-QoL) mean values (b); Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SAPS) mean values and: SWN mean values (c) and S-QoL mean values (d).

Discussion

We observed a high rate of nonadherent patients, which is in line with previous studies [David, 2010; Lambert et al. 2012]. In this study 66.6% of the total number of patients were nonadherent to long-acting injectable risperidone at 30 months (55.5% including the three patients who were continuing long-acting risperidone at their local centre with clinical data not available for the present study). On the other hand, the present study focused on already known nonadherent patients at high risk for drop out. For this reason we believe that a 33.3% rate of adherent patients must be considered a good result, obtained in a population of non-adherent subjects during 30 months of treatment.

In addition, positive and negative symptoms, subjective well-being and quality of life improved after 6, 7, 8 and 18 months of treatment, respectively; interestingly, after a significant drop-out rate observed in the first 6 months (66.6%), adherence rate remained stable (33.3%) for the rest of the observation period (24 months). We hypothesize, in agreement with other reports [Yang et al. 2012; Baloush-Kleinman et al. 2011; Schennach-Wolff et al. 2011], that improvement and maintenance of adherence is related to the amelioration of clinical features, therefore suggesting risperidone efficacy. From a critical view, in the total sample we observed an immediate response to treatment after the first month, statistically not significant (see Figure 3a and b) due to the low subjects numbers and Bonferroni post hoc conservative approach (LSD post hoc, first month: SAPS, p = 0.118; SANS, p = 0.080; second month: SAPS, p = 0.088; SANS, p = 0.028). Moreover, we noticed that significant improvement in quality of life occurred at the eighteenth month, apparently unrelated to the other parameters studied.

Analysis of results showed a reduction of clinical positive and negative symptomatology as measured by a decrease of mean values of SANS and SAPS scales during the 30-month period of pharmacological treatment.

An improvement of quality of life and wellness in patients treated with long-acting risperidone was demonstrated by the increase of mean values of SWN and S-QoL scales.

The relationship between positive and negative symptoms with subjective well-being and quality of life, as measured by analysis of linear correlations between mean values of SAPS and SANS scales with mean values of SWN and S-QoL scales showed a long-term improvement of quality of life and subjective perception that is probably simultaneous with the control of symptomatology.

Pearson correlation allowed the observation of a correlation between the relief of symptomatology and the improvement of subjective well-being and quality of life; in particular, the correlation was more significant between SAPS and SWN scales: this relation demonstrates that the decrease of positive symptomatology is associated with an increased tolerability to antipsychotics (linear coefficient = −0.933).

Analysing long-term efficacy, long-acting risperidone was found to be effective and well tolerated by patients; only a small number of them (7.4%) had to stop treatment because of side effects.

Our data show a positive influence of a long-acting risperidone over adherence to treatment, a fundamental step for the outcome estimation and symptomatologic remission, which is a highly debated concept in the treatment of schizophrenia [Cuyún Carter et al. 2011].

As shown by a meta-analysis of 10 randomized long-term trials [Leucht et al. 2011], injectable antipsychotic formulations significantly reduced relapses and drop out due to inefficacy. In our sample of long-term treated patients we did not observe episodes of recurrence or need for hospitalization related to a worsening of symptomatology.

Moreover, long-acting formulation allows for a correct pharmacological coverage after the drug administration with a significant reduction of flotation of drug plasmatic values over time [Eerdekens et al. 2004; McCutcheon et al. 2015]. Long-acting injectable therapies may help improve adherence by assuring medication delivery, moreover nonadherence can be immediately detected as soon as the clinician recognizes that a patient has not been given an injection. This early diagnosis may also allow the clinician to make prompt contact with the patient and discuss the reasons for noncompliance, coping with several issues. Although some authors [Rosenheck et al. 2011] reported that long-acting was not superior to oral risperidone in subjects with unstable schizophrenia, other data [Olivares et al. 2009; Zhornitsky and Stip, 2012] showed that adherence rates are better with long-acting injection than with oral formulations. According to these data we can, furthermore, suppose that the improved adherence to treatment could be related to patients’ preference for this long-acting formulation with no daily therapy and a better quality of life. However, it seems that long-acting drugs have lower prescribing rates than expected, with clinicians often considering long-acting therapies as a last resort in chronically ill patients [Patel et al. 2009]. Due to good short- and long-term safety and tolerability of injectable formulation drugs [Canas and Moller, 2010], with side effects often correlated to common antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychotic patients [Fleischhacker et al. 2003; Aggarwal et al. 2012], a critical argument regarding injectable formulation might be its reminder of stigma and coercive care [Niolu and Siracusano, 2005].

In addition, demographic characteristics of our sample must be considered. Patients enrolled were nonadherent with a mean age of 36.1 years. According to the long-term effectiveness of these injectable therapies [Apiquian et al. 2011; Chang et al. 2010; Taylor and Ng, 2013], long-acting risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia [Kim et al. 2008] may be one step forward leading to amelioration at this crucial period (in early adulthood), when relapses can have marked psychosocial consequences in terms of education or work opportunities.

In conclusion the naturalistic design, although interventional, is an additional key strength of our study. Another important feature of the present work is that in spite of the small sample size, patients were well-studied and well-followed-up with clinical, semi-structured interviews, and self-report instruments performed by a psychiatrist.

Study limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of the present study. Two of them are based on the small number of patients and the absence of a control group, treated with old generation depot antipsychotics. Due to the naturalistic observational design with the aim to explore the long-acting risperidone effect on psychophatholgy and functioning in nonadherent patients with schizophrenia, we decided to analyse only the data from the nine patients that completed the 30 months of clinical observation. If the exclusion of the other patients’ data (with a last observation carried forward method to handling the missing data) might introduce a selection bias, on the other hand we believe that our choice is in line with the observational nature of the study to describe the ‘real’ effect of treatment continuity. Future researches, adopting a randomized clinical trial design (with an intention-to-treat approach) between two (or more) different drug treatment strategies, might complete our observation and findings in nonadherent patients with schizophrenia. Moreover, nonadherence to treatment was assessed indirectly during the study, by evaluating patients’ observance of the risperidone administration schedule. Finally, although adherence might be influenced by the therapeutic alliance with the staff [Sapra et al. 2014; McCabe et al. 2012; Jonsdottir et al. 2013], the doctor–patient relationship was not investigated.

Conclusions

Considering the initial questions, in the subgroup of nonadherent patients, long-term treatment with long-acting risperidone showed the following results: (1) improvement of adherence to pharmacological therapy; (2) efficacy on both positive and negative symptoms; (3) improvement of quality of life; (4) increase of subjective tolerance to antipsychotics; (5) significant correlation between the reduction of positive symptoms and the perception of improvement of subjective well-being following antipsychotics; (6) absence of significant side effects related to therapy that can motivate discontinuation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Cinzia Niolu, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy Psychiatric Clinic, Fondazione Policlinico ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Emanuela Bianciardi, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Via Nomentana 1362, 00137 Rome, Italy.

Giorgio Di Lorenzo, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Claudia Marchetta, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Ylenia Barone, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy Psychiatric Clinic, Fondazione Policlinico ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Nicoletta Sterbini, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Michele Ribolsi, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

Giorgio Reggiardo, Biostatistics and Data Management Uni Medi Service, Genoa, Italy.

Alberto Siracusano, Chair of Psychiatry, Department of Systems Medicine, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy Psychiatric Clinic, Fondazione Policlinico ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy.

References

- Aggarwal N., Sernyak M., Rosenheck R. (2012) Prevalence of concomitant oral antipsychotic drug use among patients treated with long-acting, intramuscular, antipsychotic medications. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1984a) Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen N. (1984b) Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SAPS). University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Apiquian R., Córdoba R., Louzã M. (2011) Clinical outcomes of long-acting injectable risperidone in patients with schizophrenia: six-month follow-up from the Electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry in Latin America. Neuropsych Dis Treatment 7: 19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H., Faries D., Zhu B., Ernst F., Swartz M., Swanson J. (2006) Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auquier P., Simeoni M., Sapin C., Reine G., Aghababian V., Cramer J., et al. (2003) Development and validation of a patient-based health-related quality of life questionnaire in schizophrenia: the S-QoL. Schizophr Res 63: 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay Y., Chen T., Wu B., Hung C., Lin W., Hu T., Lin, et al. (2006) A comparative efficacy and safety study of long-acting risperidone injection and risperidone oral tablets among hospitalized patients: 12-week, randomized, single-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry 39: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloush-Kleinman V., et al. (2011) Adherence to antipsychotic drug treatment in early-episode schizophrenia: a six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Schizophr Res 130: 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera R. (2014) Patient outcomes within schizophrenia treatment: a look at the role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 75:30–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canas F., Moller H. (2010) Long-acting atypical injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 9: 683–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caseiro O., Pérez-Iglesias R., Mata I., Martínez-Garcia O., Pelayo-Terán J., Tabares-Seisdedos R., et al. (2012) Predicting relapse after a first episode of non-affective psychosis: A three-year follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res 46: 1099–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Tzeng D., Lung F. (2010) Treatment effectiveness and adherence in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection. Psychiatry Res 180: 16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll C. (2011) What are we looking for in new antipsychotics? J Clin Psychiatry 72: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuyún Carter G., Milton D., Ascher-Svanum H., Faries D. (2011) Sustained favorable long-term outcome in the treatment of schizophrenia: a 3-year prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry 11: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A. (2010) Treatment adherence in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 197: 431–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eerdekens M., Van Hove I., Remmerie B., Mannaert E. (2004) Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 70: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M., Gibbon M., Spitzer R., Williams J. (1997) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker W., Eerdekens M., Karcher K. (2003) Treatment of schizophrenia with long acting injectable risperidone: 12 month open-label trial of the first long-acting second- generation antipsychotic. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 1250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastpar M., Masiak M., Latif M., Frazzingaro S., Medori R., Lombertie E. (2005) Sustained improvement of clinical outcome with risperidone long-acting injectable in psychotic patients previously treated with olanzapine. J Psycopharmacol 19: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir H., Opjordsmoen S., Birkenaes A., Simonsen C., Engh J., Ringen P., et al. (2013) Predictors of medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 127: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. (2003) Strategies for improving compliance in treatment of schizophrenia by using a long acting formulation of an antypsichotic: clinical studies. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane J. (2014) Attitudinal barriers to prescribing LAI antipsychotics in the outpatient setting: communicating with patients, families, and caregivers. J Clin Psychiatry 12: e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith S., Pani B., Nick R., Emsley R., San L., Turner M., et al. (2004) Practical application of pharmacotherapy with long acting risperidone for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 55: 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Lee S., Choi T., Suh S., Kim Y., Lee E., et al. (2008) Effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injection in first-episode schizophrenia: in naturalistic setting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32: 1231–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacro J., Dunn L., Dolder C., Leckband S., Jeste D. (2002) Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry 63: 892–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert T., Olivares J., Peuskens J., DeSouza C., Kozma C., Otten P., et al. (2011) Effectiveness of injectable risperidone long-acting therapy for schizophrenia: data from the US, Spain, Australia, and Belgium. Ann Gen Psychiatry 10: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert T., Emmerson B., Hustig H., Resseler S., Jacobs A., Butcher B. (2012) Long acting risperidone in Australian patients with chronic schizophrenia: 24-month data from the e-STAR database. BMC Psychiatry 12: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser R., Bossie C., Gharabawi G., Baldessarini R. (2005) Clinical improvement in 336 stable chronically psychotic patients changed from oral to long-acting risperidone: 12 month open trial. Int J Neuropharmachol 8: 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht C., Heres S., Kane J., Kissling W., Davis J., Leucht S. (2011) Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. A critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res 127: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer J., Eerdekens E., Berry S., Eerdekens M. (2005) Safety and efficacy of long-acting risperidone in schizophrenia: 12 week, multicenter, open label study in stable patients switched from typical and atypical oral antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 656–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca P. (2008) Partial compliance in schizophrenia and the impact on patient outcomes. Psychiatry Res 161: 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder S. (2013) Monitoring treatment and managing adherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 74: e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe R., Bullenkamp J., Hansson L., Lauber C., Martinez-Leal R., Rössler W., et al. (2012) The therapeutic relationship and adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. PLoS ONE 7: e36080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon R., Beck K., Bloomfield M., Marques T., Rogdaki M., Howes O. (2015) Treatment resistant or resistant to treatment? Antipsychotic plasma levels in patients with poorly controlled psychotic symptoms. J Psychopharmacol. PII: 0269881115576688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller H., Llorca P., Sacchetti E., Martin S., Medori R., Parellada E. StoRMi Study Group (2005) Efficacy and safety of direct transition to risperidone long-acting injectable in patients treated with various antipsychotic therapies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 20: 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naber D. (1995) A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 10: 133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah H., Duchesne I., Mehnert A., Janagap C., Eerdekens M. (2004) Health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niolu C., Siracusano A. (2005) Discontinuità psicofarmacologica e aderenza. Roma: Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Olivares J., Rodriguez-Morales A., Diels J., Povey M., Jacobs A., Zhao Z., et al. (2009) Long-term outcomes in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone long-acting injection or oral antipsychotics in Spain: results from the electronic Schizophrenia Treatment Adherence Registry (e-STAR). Eur Psychiatry 24: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parellada E., Andrezina R., Milanova V., Glue P., Masiak M., Turner M., et al. (2005) Patients in early phases of schizophrenia effectively treated with risperidone long-acting injectable. J Pharmachol 19: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Taylor M., David A. (2009) Antipsychotic long-acting injections: mind the gap. Br J Psychiatry 195: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R., Krystal J., Lew R., Barnett P., Fiore L., Valley D., et al. (2011) Long-acting risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 364: 842–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapra M., Weiden P., Schooler N., Sunakawa-McMillan A., Uzenoff S., Burkholder P. (2014) Reasons for adherence and non-adherence: a pilot study comparing first- and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 7: 199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schennach R., Obermeier M., Meyer S., Jäger M., Schmauss M., Laux G., et al. (2012) Predictors of relapse in the year after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 63: 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schennach-Wolff R., Jäger M., Mayr A., Meyer S., Kühn K., Klingberg S., et al. (2011) Predictors of response and remission in the acute treatment of first-episode schizophrenia patients - is it all about early response? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21: 370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler N. (2003) Relapse and rehospitalization: comparing oral and depot antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendt K., Tracy D., Bhattacharyya S. (2015) A systematic review of factors influencing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res 225: 14–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siracusano A., Niolu C., Vella G. (1998) Continuità-Discontinuità dei disturbi psicopatologici tra età adulta ed età infantile: aspetti teorici e meccanismi. NOOS Aggiornamenti in Psichiatria 4: 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Subotnik K., Nuechterlein K., Ventura J., Gitlin M., Marder S., Mintz J., et al. (2011) Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 168: 286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Ng K. (2013) Should long-acting (depot) antipsychotics be used in early schizophrenia? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 7: 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Ko Y., Paik J., Lee M., Han C., Joe S., et al. (2012) Symptom severity and attitudes toward medication: impacts on adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 134: 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhornitsky S., Stip E. (2012) Oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and special populations at risk for treatment nonadherence: a systematic review. Schizophr Res Treatment. DOI: 10.1155/2012/407171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.