Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence of pain in cancer patients at different disease statuses, the impact of pain on physical and psychiatric functions of patients and the satisfaction of pain control of patients at outpatient clinic department in Taiwan.

Methods

Short form of the Brief Pain Inventory was used as the outcome questionnaire. Unselected patients of different cancers and different disease statuses at outpatient clinic department were included. The impacts of their current pain control on physical function, psychiatric function and the satisfaction of doctors were evaluated. Logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate whether the interference scale performed identically in the different analgesic ladders. The dependent variables were satisfaction toward physician and treatment.

Results

A total of 14 sites enrolled 2075 patients in the study. One thousand and fifty-one patients reported pain within the last 1 week. In patients whose diseases deteriorated, >60% of them need analgesics for pain control. Pain influenced physical and psychiatric functions of patients, especially in the deteriorated status. More than 80% of patients were satisfied about current pain control, satisfaction rate related to disease status, pain intensities and treatments for pain.

Conclusion

Our study found that different cancers at different statuses had pain at variable severity. Pain can influence physical and psychological functions significantly. More than 75% of subjects reported satisfaction over physician and pain management in outpatient clinic department patients with cancer pain in Taiwan.

Keywords: palliative care, cancer pain, satisfaction, physical and psychiatric function

Introduction

Pain is one of the most feared symptoms of cancer and the most common reason cancer patients seek help. A recent meta-analysis reports that 64% of patients with advanced stage or metastatic cancer experienced pain. Even after curative treatment, 33% of patients still complained of pain (1). More than one-third of patients graded their pain as moderate or severe, and this was especially true for head and neck cancer (HN) patients (2).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder, pain management passes through various steps until pain relief is achieved. Clearly, the principle goal of cancer treatment is the alleviation of symptoms, such as pain, and the maintenance or improvement of quality of life (QoL). Comprehensive pain control comprises issues such as screening, assessment, general treatment, management of associated symptoms and issues, addressing specific pain syndromes and follow-up. Despite the dissemination of several different sets of guidelines for cancer pain management and the fact that effective treatments are available for 70–90% of cases, undertreatment is still well documented (3). This phenomenon was demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Deandrea et al. that showed that cancer pain was not satisfactorily controlled in 43% of patients (4).

In addition to analgesics, effective management of cancer pain also depends on clinicians having a flexible approach and detailed knowledge regarding the range of available analgesic options and preparations. Undertreatment is usually attributed to inappropriate opioid use, which results from factors that can pertain to patients, family, institutions, society and even healthcare providers (5). Since unresolved pain detrimentally affects physical functioning, psychological well-being and social interaction (6); education and occupational guidelines are integral to the achievement of better pain control. Through prudent management, QoL can likely be improved in patients with chronic pain from cancer. A systematic review found that routine or increased assessment is instrumental to the success of pain management interventions (7). Pain assessments and dosage adjustments are much easier to conduct in ward patients than in patients who visit an outpatient clinic department (OPD), because there is usually insufficient time for such practices during OPD appointments.

In recent years, the Taiwan National Department of Health developed guidelines for cancer pain management as a step toward improving pain management. Since 2001, several studies have examined the prevalence, etiology, severity and management of cancer pain in outpatients in Taiwan (8,9). Thus, the purpose of the present study was to further investigate pain occurrence at different disease stages, the impact of pain on physical and psychiatric functions, and pain management satisfaction in OPD patients with cancer pain in Taiwan after the publication of guidelines. All the information collected from the hospitals was used to evaluate pain management satisfaction and improve QoL in cancer patients.

Patients and methods

Materials

This survey was non-interventional and did not aim to evaluate a predefined therapy or procedure. Cancer patients from 14 hospitals around Taiwan who fulfilled all of the following eligibility criteria were recruited: 18 years of age or above; visited the OPD; diagnosed with cancer; provided written informed consent. Any of the following criteria disqualified the patient from participation: known or suspected psychotic disease or mental retardation; unconscious subjects. After the subjects signed the informed consent form, they completed the questionnaire in another room. This questionnaire assessed pain intensity, QoL and satisfaction. The investigators also filled out a questionnaire regarding the patient's diagnosis, disease status, etiology of pain and treatment medication. The categories of disease status were as follows: ‘disease free’ (DF), which meant that there was no evidence of disease recurrence after curative treatment; ‘relief’ indicated that the disease was stable and that the patient was partially or completely responsive to palliative treatment; ‘deterioration’ indicated that the disease was progressing. Patients were only assessed during one OPD visit.

Measures

The questionnaire was based on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (10). The BPI short form is one of the most widely used tools for multidimensional cancer pain assessment. It has been validated as a measure of cancer pain across many cultures and languages, and was recommended as a cancer pain assessment tool for palliative care patients by the Expert Working Group of the European Association of Palliative Care. The BPI was developed to provide a quick and easy means of measuring pain intensity and the extent to which pain interferes with the lives of pain sufferers. On the BPI, patients rate on a scale from 0 (‘no pain’) to 10 (‘pain as bad as you can imagine’) the intensity of their current pain as well as that of the previous 24 h at its worst, least and average. Patients were also asked to rate the extent to which their pain interfered with seven QoL domains (general activity, walking, mood, sleep, work, relations with other persons and enjoyment of life) on a scale of 0 (‘does not interfere’) to 10 (‘interferes completely’). Scores of all four pain intensity items and seven interference items were summed. In addition to the more widely used total interference index, the seven interference items were also grouped into two subscales: pain interference with physical functions (general activity, walking ability and normal work) and psychological functions (mood, relations with other, enjoyment of life and sleep). Participants also answered the following two questions: (i) how satisfied are you with the way your doctor treated your pain? and (ii) are you satisfied with the pain control? The response options for these questions were as follows: very unsatisfied, not satisfied, fair, satisfied and very satisfied.

Since this was a clinical Phase IV study and only descriptive data were obtained, no formal statistical considerations were employed in determining the sample size.

Statistical analysis

All eligible data were used for data analysis. The results were summarized using descriptive statistics. For continuous variables, the number, mean, standard deviation, minimum, median and maximum were presented. For categorical variables, the number and percentages of subjects in each class were presented. Logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate whether the interference scale performed identically in the different analgesic ladders. The dependent variables were satisfaction toward physician and satisfaction with treatment in two separate analyses. Independent variables were background characteristics such as sex, age, primary cancer, use of analgesics, pain intensity and pain interference.

Ethics approval

The local Institutional Review Board committee at each hospital gave approval for the aggregated anonymous data to be analyzed and published and the ethics committee specifically approved this entire study. These hospitals are (i) E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; (ii) Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; (iii) Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; (iv) Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; (v) National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; (vi) Linko Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan; (vii) Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; (viii) Changhua Show-Chwan Memorial Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; (ix) Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan; (x) Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; (xi) Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan; (xii) Chia-Yi Christian Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan; (xiii) Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan; (xiv) China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

Results

Samples

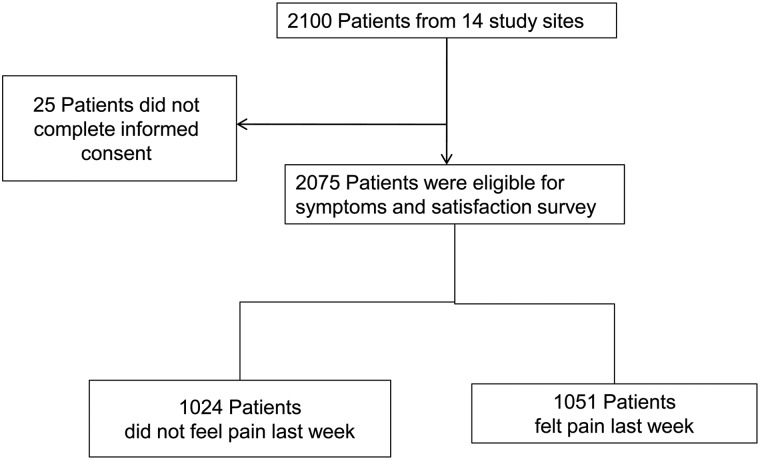

A total of 14 sites enrolled 2075 patients in the study. One thousand and fifty-one patients reported pain within the previous week and were eligible for functional assessment. The derivation of the sample is shown in Fig. 1. Summary statistics of demographic characteristics for all subjects are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 57.47 ± 13.20 years. There were more female (52.19%) than male patients (47.81%). Breast cancer (BC) and gastrointestinal (GI) cancer (including colorectal) were the most common cancers, followed by HN cancer, which has a high incidence in Taiwan. More than 50% of subjects had relief from the disease at the time of evaluation.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients included in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible patients

| Mean ± SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.47 ± 13.20 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 992 (47.81) |

| Female | 1083 (52.19) |

| Primary cancer | |

| Head and neck | 309 (14.89) |

| Gastrointestinal and colon/rectum | 394 (18.99) |

| Hepatobiliary and pancreas | 120 (5.78) |

| Breast | 527 (25.40) |

| Lung and mediastinum | 184 (8.87) |

| Blood/lymphoma | 314 (15.18) |

| GYN and GU | 133 (6.41) |

| Other | 93 (4.48) |

| Disease status | |

| Disease free | 407 (19.61) |

| Relief | 1226 (59.08) |

| Deterioration | 442 (21.30) |

SD, standard deviation; GYN, gynecological; GU, genitourinary.

Measures

Most patients who experienced pain required treatments throughout the entire course of their illness, as shown in Table 2. This percentage increased as current disease status worsened. Indeed, 81.90% of patients with a deterioration status experienced pain, compared with 54.05% of patients with a DF status. The same trends were also evident in subjects' responses to the questions, ‘Have you had pain in the past week?’ and ‘Did you take any analgesics within the last week?’ While an improving disease status was associated with fewer episodes of pain and less demand for analgesics, the need for analgesics never reached zero; thus, patients showing improvement should nonetheless continue to undergo regular pain evaluations.

Table 2.

Disease status and analgesic drug history

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you had pain that has required treatment throughout the entire course of your cancer? | |||

| Disease free | 220 (54.05) | 187 (45.95) | <0.001 |

| Relief | 858 (69.98) | 368 (30.02) | <0.001 |

| Deterioration | 362 (81.90) | 80 (18.10) | <0.001 |

| Have you experienced pain in the past week? | |||

| Disease free | 131 (32.19) | 276 (67.91) | <0.001 |

| Relief | 596 (48.61) | 630 (51.39) | <0.001 |

| Deterioration | 324 (73.30) | 118 (26.70) | <0.001 |

| Did you take any analgesics within the past week? | |||

| Disease free | 68 (16.71) | 339 (83.29) | <0.001 |

| Relief | 426 (34.75) | 800 (65.25) | <0.001 |

| Deterioration | 274 (61.99) | 168 (38.01) | <0.001 |

Demand for analgesics also increased when disease status worsened. There were 20% of patients who were DF but still needed analgesics; this was especially true for HN cancer patients. In some cases, residual pain is due to consequences of previous anticancer treatments, such as scarring after an operation, radiation fibrosis, adhesion bands or neuropathy; however, in other instances, it derives from non-cancer causes. More than 60% of patients with a deteriorated disease status required analgesics for pain control (Table 3).

Table 3.

Disease status and the distribution of painkiller usage

| Primary cancer | Disease free (%) | Relief (%) | Deterioration (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 25.0 | 46.3 | 71.2 | <0.001 |

| GI and colon | 16.1 | 26.6 | 57.9 | <0.001 |

| Hepatobiliary and pancreas | 41.7 | 40.4 | 62.8 | 0.056 |

| Breast | 11.5 | 31.0 | 64.2 | <0.001 |

| Lung and mediastinum | 20.0 | 49.2 | 64.6 | 0.023 |

| Blood/lymphoma | 25.0 | 26.7 | 45.7 | 0.057 |

| GYN and GU | 16.7 | 33.7 | 59.4 | 0.010 |

| Other | 11.1 | 42.1 | 63.0 | 0.019 |

| Average | 20.9 | 37.0 | 61.1 | <0.001 |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Different cancers have different treatment courses and metastatic sites, so the prevalence of pain varies. For instance, concurrent chemoradiotherapy, either neoadjuvant or adjuvant, is one of the major treatments for HN cancer, but the acute and chronic side effects from treatments, such as mucositis, subcutaneous fibrosis and neuropathy occur during or after treatment, even if the patient is in a DF status. In recurrent cancer, there are variations in pain severity across different metastatic sites. We analyzed the data from the 1051 patients who experienced pain within the previous week, to determine the severity of different cancers at different disease statuses (Table 4). There were few differences in HN patients of different disease statuses. However, in BC and lung cancer (LC) patients, deteriorated patients reported greater pain than did DF patients, possibly because these two diseases are commonly associated with more extensive metastasis, particularly bone metastasis. Although patients of hepatobillary cancer (HB), pancreatic cancer (PC), gynecologic cancer and genitourinary cancers who were DF also reported more pain than did patients at a deteriorated status, the case number was too small to reach significance.

Table 4.

Average pain scores over the past week

| Primary site | Disease free Mean ± SD (n), N = 131 |

Relief Mean ± SD (n), N = 596 |

Deterioration Mean ± SD (n), N = 324 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 3.95 ± 2.22 (19) | 3.73 ± 2.00 (104) | 3.98 ± 2.10 (61) | 0.7254 |

| GI and colon | 4.43 ± 2.36 (21) | 3.43 ± 1.74 (90) | 3.62 ± 1.89 (61) | 0.0937 |

| Hepatobiliary and pancreas | 5.00 ± 4.24 (4) | 2.45 ± 1.34 (31) | 4.03 ± 1.85 (40) | 0.0007 |

| Breast | 2.75 ± 1.53 (59) | 3.43 ± 1.79 (127) | 4.15 ± 1.84 (59) | <0.0001 |

| Lung and mediastinum | 3.33 ± 1.53 (3) | 3.52 ± 2.08 (67) | 4.47 ± 2.02 (34) | 0.0867 |

| Blood/lymphoma | 2.47 ± 1.61 (19) | 3.33 ± 1.87 (105) | 3.31 ± 1.57 (26) | 0.1558 |

| GYN and GU | 5.50 ± 6.36 (2) | 3.17 ± 1.92 (46) | 4.20 ± 1.64 (24) | 0.0499 |

| Others | 2.25 ± 0.50 (4) | 3.77 ± 1.90 (26) | 3.89 ± 1.91 (19) | 0.2682 |

We further analyzed the impact of pain control on the physical function of cancer patients. Results indicated that pain could influence the functional status of patients, and disease-deteriorated patients typically exhibited worse physical function than did patients with a relief status. Such trends were more common in HN, HB and PC, BC and LC patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Physical function affected by pain across different types of cancer

| Primary site | Disease free Mean ± SD (n), N = 131 |

Relief Mean ± SD (n), N = 596 |

Deterioration Mean ± SD (n), N = 324 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 2.25 ± 2.31 (19) | 2.83 ± 2.55 (104) | 3.97 ± 3.05 (61) | 0.0111 |

| GI and colon | 2.41 ± 2.44 (21) | 2.90 ± 2.63 (90) | 3.46 ± 2.81 (61) | 0.2376 |

| Hepatobiliary and pancreas | 5.17 ± 5.59 (4) | 2.44 ± 2.46 (31) | 4.56 ± 3.18 (40) | 0.0121 |

| Breast | 1.71 ± 1.96 (59) | 3.44 ± 2.97 (127) | 4.42 ± 2.97 (59) | <0.0001 |

| Lung and mediastinum | 4.33 ± 3.51 (3) | 2.84 ± 2.64 (67) | 4.83 ± 3.36 (34) | 0.0057 |

| Blood/lymphoma | 2.07 ± 2.09 (19) | 2.58 ± 2.84 (105) | 3.10 ± 2.78 (26) | 0.4565 |

| GYN and GU | 4.00 ± 5.66 (2) | 3.97 ± 3.02 (46) | 4.46 ± 2.56 (24) | 0.8026 |

| Others | 3.41 ± 4.57 (4) | 3.63 ± 3.20 (26) | 4.68 ± 3.55 (19) | 0.5620 |

| P value | 0.0831 | 0.0454 | 0.1768 |

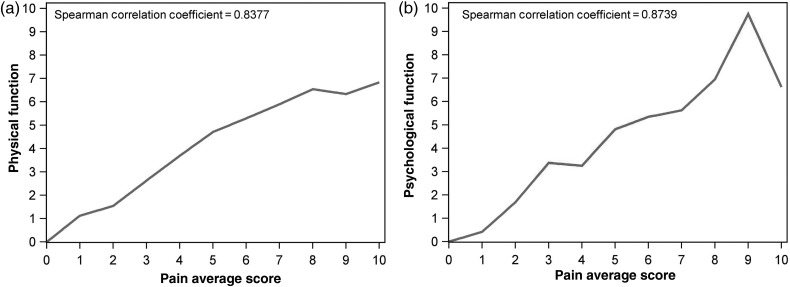

However, in addition to pain, patients with these cancers might have experienced a number of other symptoms at deteriorated status. For example, patients with advanced or recurrent HN might have had cosmetic and feeding problems; HB and PC patients might have had decompensated liver function and peritoneal seeding with intestinal obstruction; progressed BC and LC patients had a higher incidence of bone metastasis, plural effusion and brain metastases. All of these symptoms could result in more severe pain and a greater decline in physical function. We also determined the influence of disease status and pain intensity on the psychological functioning of patients with different cancer types. Through examination of the descriptive data and univariate analysis, we found that psychological function was more negatively impacted by pain in patients with GI cancer, BC and LC, differences between cancers decreased as disease was progressing (Table 6). The effects of pain on physical and psychological functions are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 6.

Psychological function influenced by pain on different types of cancer

| Primary site | Disease free Mean ± SD (n), N = 131 |

Relief Mean ± SD (n), N = 596 |

Deterioration Mean ± SD (n), N = 324 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HN | 3.38 ± 2.68 (19) | 3.75 ± 2.63 (104) | 4.01 ± 2.75 (61) |

| GI and colon | 2.48 ± 2.34 (21) | 3.02 ± 2.69 (90) | 3.88 ± 2.66 (61) |

| Hepatobiliary and pancreas | 5.00 ± 5.49 (4) | 2.70 ± 2.56 (31) | 4.43 ± 2.34 (40) |

| Breast | 1.70 ± 1.85 (59) | 3.07 ± 2.51 (127) | 4.15 ± 2.64 (59) |

| Lung and mediastinum | 3.17 ± 1.88 (3) | 2.89 ± 2.37 (67) | 3.89 ± 2.74 (34) |

| Blood and lymphoma | 1.54 ± 1.93 (19) | 2.51 ± 2.45 (105) | 2.61 ± 2.21 (26) |

| GYN and GU | 2.63 ± 3.71 (2) | 3.16 ± 2.61 (46) | 3.94 ± 2.56 (24) |

| Others | 1.93 ± 2.29 (4) | 3.13 ± 2.76 (26) | 4.89 ± 3.25 (19) |

| P | 0.0253 | 0.0649 | 0.1501 |

HN, head and neck.

Figure 2.

Correlation of pain intensity with physical (a) and psychological (b) functions.

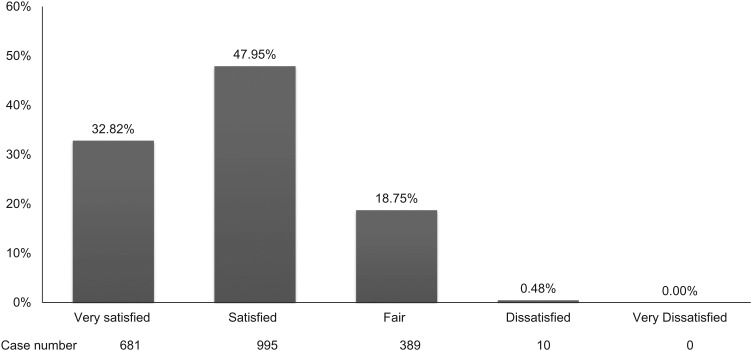

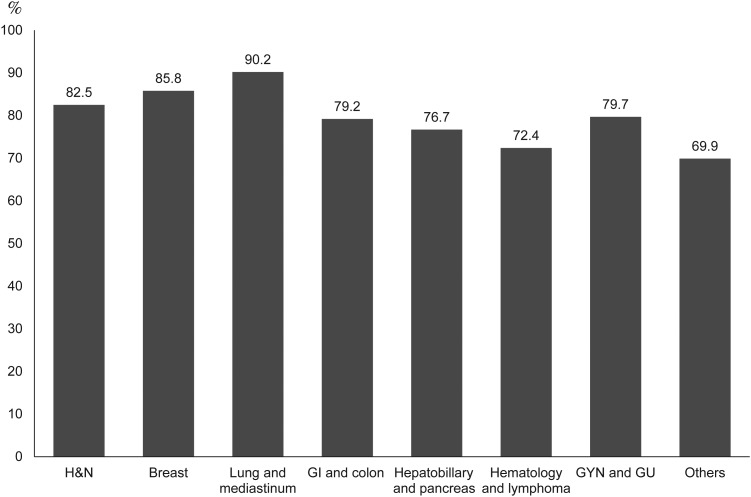

Finally, we asked a total of 2075 patients to rate their satisfaction with their current level of pain control. More than 80% of patients were satisfied with their current pain control, whereas only 0.48% of patients were dissatisfied (Fig. 3). Although HN, BC and LC patients experienced more pain at all status, >80% of these patients were nevertheless satisfied with their doctors, compared with 72.4% of hematologic malignancy and lymphoma patients (Fig. 4). Satisfaction rate related to disease status, pain intensity and pain treatment (data not shown). Advanced disease status, more severe pain and less aggressive treatment with analgesics all related to lower satisfaction.

Figure 3.

Patients' satisfaction about pain control.

Figure 4.

Satisfied with doctors in different cancers. H&N, head and neck; GI, gastrointestinal; GYN, gynecological; GU, genitourinary.

Discussion

The management of cancer-related pain is a primary challenge for cancer care doctors. Cancer-related pain may result from the cancer itself or from associated treatments (11). Effective evaluation and correct differential diagnosis of pain depend on the doctor's experience and good communication. When assessing pain in cancer patients, practitioners should characterize the pain complaint; consider the disease status; clarify the pain in terms of cause, syndrome and pathophysiology; and identify other factors that may be contributing to the illness burden (12). Barriers to effective pain management include lack of awareness of patients' symptoms, inadequate training of clinicians concerning opioid abuse and poor patient–doctor communication (13,14). In a systemic review, Deandrea et al. (15) reported that nearly one in two patients with cancer pain is undertreated. Because of a significant evolution in the types of available anticancer treatments, more patients are being cured or at least living longer; however, up to 40% of 5-year cancer survivors report pain (16). Persistent pain will lead to poorer general health, physical, role and social functioning in cancer survivors (17).

Recently, a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment and patient attitudes about cancer-related pain found that pain severity was quite variable within different kinds of cancers and different countries. Of 5084 patients, 56% suffered moderate-to-severe pain at least monthly, and 50% believed that their QoL was not considered a priority by their healthcare professional. Despite more than two decades of education in Europe, greater insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms of pain, and the wider availability of antinociceptive therapies, treatment of cancer pain is still suboptimal (1). In 2001, we conducted the first prospective, patient-focused survey that assessed the prevalence, severity and management of cancer-related pain in oncology OPDs in Taiwan; of 480 cancer patients from 15 hospitals, pain was reported by 257 patients (54%), and severe pain was reported by 35% of patients. Only 149 of the patients who reported pain were receiving analgesia, and 64% of them (95 of 149) were satisfied or very satisfied with the pain control (8), which was lower than observed in our current study. After many years of education, opioid consumption in Taiwan increased by 55% from 362 to 560 defined daily dose per million inhabitants per day from 2002 to 2007 (18). Increased morphine consumption might be an important indicator of our progress in cancer pain relief.

Patients at different disease statuses also experience different grades of pain. A meta-analysis found that patients who received curative treatment had less severe pain than did patients who were still receiving anticancer treatments or who were at the advanced/terminal stage. In all cancer types, pain prevalence was >50%; the highest prevalence was found in HN patients (70%). Pain prevalence in patients during anticancer treatment (59%) was not significantly different from that of patients with advanced/metastatic disease (64%) (2). In our study, the prevalence of pain and the need for analgesics were lower in patients who were DF than patients with a relief or deterioration status. More than 50% of patients with a DF status had never experienced pain severe enough to require treatment throughout the entire course of the disease. However, this finding might be inaccurate, as surgery is the most important curative treatment for solid tumors, and analgesics would likely be necessary at least after surgery. Accompanying the progression of disease, patients reported more incidences of pain and a greater need for analgesics within the previous week (Table 2).

In our study, greater pain with disease deterioration was most pronounced in LC, gynecological cancer and BC. These three cancers have a higher incidence of bone metastasis and complications from bone metastasis. In HN, in contrast, pain was the greatest in the DF group. This may have been because the major treatments for HN were neoadjuvant/adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy and/or surgery, which usually lead to severe mucositis, skin or muscle contracture and limitation of mobility. In patients with hematologic malignancy or lymphoma, which was classified as ‘low risk of pain,’ pain severity at different statuses was similar to that of other cancers. In addition, satisfaction with pain management in blood cancer/lymphoma patients was lower than that of patients with other definite cancers. Such a result reinforces the importance of pain assessment, even in the so-called ‘low risk of pain’ groups.

One substantial stressor for cancer patients is the fear of losing independence and the ability to engage in physical activity. A clinical research study found a strong interaction among fatigue, pain, sleep disturbances and distress (19). In contrast, physical activity, especially exercise, improves depressive symptoms and pain (20,21). The relationship between pain and physical activity in cancer patients varies with disease status. Patients with advanced disease usually experience limitations in physical activity. But even when patients are DF, pain may still arise from complications of adjuvant treatments, worsening the QoL (22). In the current study, we found that pain differentially impacts physical function across disease status and cancer type. At DF status, BC patients reported the greatest preservation of physical function; however, pain greatly influenced the daily activities of GI and colon cancer patients, who typically had residual complications from previous surgery, such as adhesion, partial obstruction or colostomy. We also found that the effect of pain on physical function differed significantly as a function of disease status. Specifically, as the disease progressed, pain impaired physical function to a greater extent. There were several reasons for this finding: more extensive metastatic sites, more treatments including chemotherapy or radiotherapy, more analgesics, more severe depressive mood and possibly more severe malnutrition and cachexia. BC was a typical example: once the disease worsened, physical function also deteriorated quickly. Thus, the type of primary cancer, disease status, severity of dysfunction, family support and estimated residual life should all be considered when arranging therapeutic programs, daily activities and facilities for patients.

Pain is also a negative and stressful experience for cancer patients, just like depression, anxiety, stress, fatigue and psychosocial factors all affect cancer patients (23). Since more severe pain usually accompanies disease progression, patients with pain are at higher risk for depression and anxiety (24). Depression is also associated with a number of other risk factors such as reduced QoL, poor adherence to treatments, suicidal ideation and the drug–drug interaction between antidepression and antineoplastic agents (25,26). In our study, when cancer progressed, pain would aggravate the loss of psychological function in most patients, especially in BC patients. However, regardless of which cancer type is associated with the greatest pain-related risk to psychiatric function, all care-givers should be vigilant of changes in mood, sleep, interpersonal relations and enjoyment of life in patients, especially, when the disease progresses. Oncologists should receive extensive training in communication skills so that they can more effectively discuss psychological problems with their patients. However, somatic problems, such as hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency and drug effects should be ruled out before diagnosing a patient with a psychiatric problem. Oncologists, psychiatrists, nurses and even social workers should all work together to address the psychiatric problems of cancer patients. As reported in a systematic review, exercise training, cognitive behavior therapy and complementary therapy, followed by meeting with a psychologist, are the most frequently employed interventions for cancer patients with cancer-related psychological distress (27).

Patient compliance is also important in effective pain management. Interference with physical function remains a major problem in cancer pain patients and can affect psychiatric conditions and compliance. In our study, 79.7% of patients were in a disease-free or relief status and, among them, 47.95% were satisfied and 32.82% were very satisfied. In summary, >75% of subjects were satisfied with their physician and cancer pain treatment.

Disease deterioration occurs even in cancers that were initially under control. Thus, for patients with pain, persistent evaluation and adequate treatment may be key to improving patient satisfaction, which may translate to better compliance. One review reported that institutional models, clinical pathways and consultation services represent three alternative models for the integration of care processes in cancer pain management (28). In order to realize these models, a multidisciplinary team is necessary. Such a team is particularly important for the treatment of patients who receive their analgesics and follow-up care at OPDs where time is often insufficient for doctors to devise a pain management plan. Another issue is patient compliance; one study reported that even among patients who suffered from pain, the majority still believed that opioids were dangerous and should not be used frequently (29). Indeed, the adherence rate for around-the-clock opioid analgesics is only 63.6% (30). Thus, to maximize pain control, adherence to the prescribed opioid regimen should be given high priority.

There are some limitations to our study. The first is that our questionnaire did not assess dosage and the route of administration information for the most potent analgesic prescribed, or associations with analgesic adjuvant drugs (i.e. antidepressants, anticonvulsants) or other non-pharmacological therapies. Another limitation is that the study design was cross-sectional. To further explore the causal links between pain and other physical or psychospiritual factors, a longitudinal study would be ideal.

In conclusion, our study collected data on the current pain control status of patients of outpatient clinics in several hospitals at Taiwan. Pain can significantly influence physical and psychological functions. Compared with our previous survey, although >75% of the surveyed OPD patients with cancer pain reported satisfaction with their physician and pain management, there were still quite a few patients suffered from pain. More education and trainings for guidelines of pain control are urgently needed. No matter patients who are DF, relief from disease or disease deterioration, continuous evaluation and effective treatment of patients at every status of cancer survival are the cornerstones of satisfied control of pain.

Funding

This work was supported by a program grant from Johnson & Johnson. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Janssen Taiwan.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B et al. . Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol 2009;20:1420–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1437–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadad AR, Browman GP. The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management. Stepping up the quality of its evaluation. JAMA 1995;274:1870–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weingart SN, Cleary A, Stuver SO et al. . Assessing the quality of pain care in ambulatory patients with advanced stage cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:1072–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stromgren AS, Sjogren P, Goldschmidt D, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M. Symptom priority and course of symptomatology in specialized palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy S et al. . Quality measures for symptoms and advance care planning in cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4933–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh RK. Pain control in Taiwanese patients with cancer: a multicenter, patient-oriented survey. J Formos Med Assoc 2005;104:913–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng WL, Wu GJ, Sun WZ, Chen JC, Huang AT. Multidisciplinary management of cancer pain: a longitudinal retrospective study on a cohort of end-stage cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:444–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC.. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 1983;17:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grond S, Zech D, Diefenbach C, Radbruch L, Lehmann KA. Assessment of cancer pain: a prospective evaluation in 2266 cancer patients referred to a pain service. Pain 1996;64:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portenoy RK. Treatment of cancer pain. Lancet 2011;377:2236–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIH State-of-the-Science Statement on symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2002;19:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobsen R, Moldrup C, Christrup L, Sjogren P. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: a systematic exploratory review. Scand J Caring Sci 2009;23:190–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol 2008;19:1985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson KO, Richman SP, Hurley J et al. . Cancer pain management among underserved minority outpatients: perceived needs and barriers to optimal control. Cancer 2002;94:2295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T, Loeffler DR. Cancer-related chronic pain: examining quality of life in diverse cancer survivors. Cancer 2011;117:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan HH, Ho ST, Lu CC, Wang JO, Lin TC, Wang KY. Trends in the consumption of opioid analgesics in Taiwan from 2002 to 2007: a population-based study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortimer JE, Barsevick AM, Bennett CL et al. . Studying cancer-related fatigue: report of the NCCN scientific research committee. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:1331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craft LL, Vaniterson EH, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Courneya KS. Exercise effects on depressive symptoms in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatham B, Smith J, Cheifetz O et al. . The efficacy of exercise therapy in reducing shoulder pain related to breast cancer: a systematic review. Physiother Canada Physiotherapie Canada 2013;65:321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown JC, Mao JJ, Stricker C, Hwang WT, Tan KS, Schmitz KH. Aromatase Inhibitor Associated Musculoskeletal Symptoms are associated with Reduced Physical Activity among Breast Cancer Survivors. Breast J 2014;20:22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Sousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: a clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2012;15:120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawdin B, Evans C, Rabow MW. The relationships among hope, pain, psychological distress, and spiritual well-being in oncology outpatients. J Palliat Med 2013;16:167–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colleoni M, Mandala M, Peruzzotti G, Robertson C, Bredart A, Goldhirsch A. Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. Lancet 2000;356:1326–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miguel C, Albuquerque E. Drug interaction in psycho-oncology: antidepressants and antineoplastics. Pharmacology 2011;88:333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh ML, Chung YC, Hsu MY, Hsu CC. Quantifying psychological distress among cancer patients in interventions and scales: a systematic review. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2014;18:399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brink-Huis A, van Achterberg T, Schoonhoven L. Pain management: a review of organisation models with integrated processes for the management of pain in adult cancer patients. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:1986–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang SY, Tung HH, Wu SF et al. . Concerns about pain and prescribed opioids in Taiwanese oncology outpatients. Pain Manag Nurs 2013;14:336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang SY, Wu SF, Tsay SL, Wang TJ, Tung HH. Prescribed opioids adherence among Taiwanese oncology outpatients. Pain Manag Nurs 2013;14:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]