Abstract

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) remains an incurable disease, and approximately 25% of patients with HER2+ early breast cancer still relapse after adjuvant trastuzumab-based treatment. HER2 is a validated therapeutic target that remains relevant throughout the disease process. Recently, a number of novel HER2 targeted agents have become available, including lapatinib (a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of both HER2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor), pertuzumab (a new anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody) and ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1, a novel antibody–drug conjugate), which provide additional treatment options for patients with HER2+ MBC. The latest clinical trials have demonstrated improved outcome with treatment including pertuzumab or T-DM1 compared with standard HER2 targeted therapy. Here we review the clinical development of approved and investigational targeted agents for the treatment of HER2+ MBC, summarize the latest results of important clinical trials supporting use of these agents in the treatment of HER2+ MBC, and discuss how these results impact therapeutic options in clinical practice.

Keywords: breast cancer, HER2, lapatinib, pertuzumab, ado-trastuzumab emtansine

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer death for women in the United States. It is estimated that about 231,000 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer and over 40,000 will die from the disease in 2015 [Siegel et al. 2015]. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positivity, determined by either protein overexpression or gene amplification or both, is found in 25–30% of breast cancers. Regardless of stage, HER2 positivity in the absence of HER2 targeted therapy is associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and significantly shortened disease-free and overall survival [Slamon et al. 1987, 1989].

Trastuzumab (Herceptin®, Genentech, San Francisco, CA, USA) was the first HER2 targeted agent to be approved for HER2-positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in 1998 and for early stage disease in 2006 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The addition of trastuzumab to standard chemotherapy has significantly improved survival for patients with HER2+ disease in both settings [Slamon et al. 2001, 2011; Marty et al. 2005; Robert et al. 2006; Seidman et al. 2008; Joensuu et al. 2009; Goldhirsch et al. 2013; Gianni et al. 2014; Perez et al. 2014]. However, HER2+ MBC remains an incurable disease and approximately 25% of patients with this form of early stage breast cancer still relapse after 1 year of adjuvant-based treatment [Goldhirsch et al. 2013; Perez et al. 2014]. Thus, there has been an unmet need to develop novel agents with the potential to improve survival of patients with HER2+ MBC. In recent years, a number of novel HER2 targeted agents have become available, including lapatinib (Tykerb®, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK), pertuzumab (Perjeta®, Genentech) and ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1, Kadcyla®, Genentech).

In this article, we review the clinical development of approved and investigational targeted agents for HER2+ MBC, summarize the latest results of important clinical trials that support these agents in HER2+ MBC, and discuss how the latest results have already improved our therapeutic options in clinical practice.

Approved HER2 targeted agents for HER2+ MBC

Trastuzumab

Trastuzumab is a humanized recombinant monoclonal antibody that targets the HER2 protein. It binds to the extracellular domain IV of the HER2 receptor to block homodimerization of HER2 receptor. In the pivotal phase III trial that led to the first regulatory approval of trastuzumab, 469 women with HER2+ MBC were randomized to standard chemotherapy alone versus chemotherapy plus trastuzumab. The addition of trastuzumab to chemotherapy was associated with longer time to progression (TTP) (7.4 versus 4.6 months, p < 0.001), higher overall response rate (ORR) (50% versus 32%, p < 0.001), longer duration of response (9.1 versus 6.1 months, p < 0.001) and longer overall survival (OS) (25.1 versus 20.3 months, p = 0.046). The primary toxicity was cardiotoxicity, most prominent in patients receiving the combination of trastuzumab and anthracycline but less clinically significant in those receiving paclitaxel (16% versus 2%). Hence the use of anthracyclines in combination with trastuzumab in the metastatic setting is generally not recommended [Slamon et al. 2001].

Based on this trial, trastuzumab was approved in combination with paclitaxel for first-line treatment of HER2+ MBC in 1998. One additional randomized, multicenter, multinational trial evaluated docetaxel with or without trastuzumab in the first-line metastatic setting [Marty et al. 2005]. Interestingly, although TTP and ORR were significantly improved, estimated OS was similar in the control patients who crossed over to trastuzumab on progression and the docetaxel plus trastuzumab group (30.3 versus 31.2 months). These data also demonstrated the effectiveness of trastuzumab even when used in the second-line setting. Subsequent trials evaluated trastuzumab alone or with multiple different agents or combinations. Single-agent trastuzumab was active and well tolerated as first-line treatment of women with HER2+ MBC [ORR 26–34%, clinical benefit rate (CBR) 48%, TTP 3.8 months] [Vogel et al. 2002], but the survival benefit with combination therapy made single agent therapy less appealing. Generally, single agent trastuzumab has been used as maintenance therapy following response to trastuzumab and chemotherapy combinations. Essentially all combination studies have demonstrated safety and efficacy, although the majorities are single arm trials, and in many countries. trastuzumab combinations have become the standard of care for patients with HER2+ MBC regardless of the chemotherapy agent used and efficacy [Nielsen et al. 2013].

Unfortunately, the vast majority of patients with HER2+ MBC who initially respond to trastuzumab will experience disease progression. Preclinical studies as well as nonrandomized trials suggested improved efficacy when trastuzumab was continued in combination with a new chemotherapy agent following disease progression [Gelmon et al. 2004; Tripathy et al. 2004; Bartsch et al. 2007]. However, there are few randomized studies aiming at evaluating this treatment strategy. The German Breast Group 26/Breast International Group 03–05 study is the only randomized phase III trial that has investigated continued trastuzumab in combination with capecitabine compared with capecitabine alone in patients whose cancers progressed on trastuzumab and taxane combination therapy in the first-line setting [von Minckwitz et al. 2009, 2011]. Due to the approval of lapatinib combined with capecitabine (see below), enrollment to this study was slow and the study was closed to accrual before its intended accrual goal was met (156 versus 482 planned accrual). Despite this, continuation of trastuzumab with capecitabine compared with capecitabine alone resulted in a significant improvement in ORR (48.1% versus 27.0%, p = 0.0115) and TTP (8.2 versus 5.6 months, p = 0.0338), although the numerical improvement in OS was not significant due to underpowering (24.9 versus 20.6 months, p = 0.73).

Despite the success of trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy, approximately 30–50% of patients with naïve HER2+ MBC do not achieve an objective response in the first-line setting indicating de novo resistance to trastuzumab, and TTP as well as survival remains short (7–17 months, 22–38 months, respectively) [Slamon et al. 2001; Baselga et al. 2012; Nielsen et al. 2013; Swain et al. 2013] (Table 1).This had led to intense interest in the development of alternative approaches to block signaling through the HER2 pathway, with resulting significant improvements in outcome as outlined below.

Table 1.

Major clinical trials of approved HER2-targeted agents for HER2+ MBC.

| Agent | Study | Phase | Number of patients | Treatment regimen | Outcomes | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line | ||||||

| Trastuzumab | Vogel et al. [2002] | II | 114 | Trastuzumab | ORR: 26% CBR: 48% |

Chills : 25% asthenia :23% fever : 22% pain :18% nausea :14% cardiacdysfunction:2% |

| Slamon et al. [2001] | III | 469 | Trastuzumab+chemotherapy (paclitaxel /AC/ EC) versus chemotherapy (paclitaxel / AC/ EC) |

ORR: 50 versus 32% (p < 0.001) TTP: 7.4 versus 4.6 months (p < 0.001) OS: 25.1 versus 20.3 months ( p = 0.046) |

Cardiac dysfunction:27% (in AC/ EC + trastuzumab arm) versus 13% (in paclitaxel +trastuzumab arm) versus 8% (in AC/ EC arm) versus 1% (in paclitaxel arm) |

|

|

M77001- Marty et al. [2005] |

II | 186 | Trastuzumab+docetaxel versus docetaxel |

ORR: 61% versus 34% (p = 0.0002) TTP: 11.7 versus 6.1 months (p = 0.0001) OS: 31.2 versus 22.7 months (p = 0.0325) |

Grade 3/4 events: neutropenia: 32 versus 22% febrile neutropenia:23 versus 17% Symptomatic heart failure: 1% versus 0% |

|

| Pertuzumab | CLEOPATRA- Baselga et al.[2012] Swain et al. [2015] |

III | 808 | Pertuzumab+trastuzumab+docetaxel versus trastuzumab+docetaxel | PFS : 18.5 versus 12.4 months (p < 0.001) OS: 56.5 versus 40.8 months ( p < 0.001) ORR: 80.2 versus 69.3% (p = 0.001) |

Grade 3/4 events: diarrhea: 9.3 versus 5.1% no increase in left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| VELVET -Andersson et al. [2014] | II | 213 | Pertuzumab+trastuzumab+ vinorelbine |

ORR: 62.9% PFS: 14.3 months |

||

| T-DM1 | TDM4450g- Hurvitz et al. [2013] |

II | 137 | T-DM1 versus trastuzumab+ docetaxel |

PFS: 14.2 versus 9.2 months (p = 0.037) ORR: 64.2 versus 58% |

Grade ≥3 events: 46.4 versus 90.9% adverse events leading to treatment discontinuations: 7.2 versus 40.9% |

| MARIANNE- Ellis et al.[2011]. Ellis et al.[2015] |

III | 1095 | T-DM1+pertuzumab versus T-DM1 versus trastuzumab+ taxane (docetaxel or paclitaxel) |

ORR: 64.2 versus 59.7 versus 67.9% PFS: 15.2 versus 14.1 versus 13.7 months |

Grade 3-5 events: neutropenia: 2.7 versus 4.4 versus 19.8% anemia: 6.0 versus 4.7 versus 2.8% AST increased: 3.0 versus 6.6 versus 0.3% thrombocytopenia: 7.9 versus 6.4 versus 0% |

|

| Lapatinib | CTG MA.31 -Gelmon et al. [2015]. |

III | 53 | Lapatinib + taxane followed by lapatinib versus trastuzumab + taxane followed by trastuzumab | PFS: 9.1 versus 13.6 months (p < 0.001) | Grade 3/4 events: diarrhea: 19 versus 1% rash: 8 versus 0% |

| Second-line | ||||||

| Trastuzumab | GBG 26/BIG 3-0-von Minckwitz et al. [2009, 2011] | III | 156 | Trastuzumab+capecitabine versus capecitabine |

ORR: 48.1 versus 27% (p = 0.0115) TTP: 8.2 versus 5.6 months (p = 0.0338) OS: 24.9 versus 20.6 months (p = 0.73) |

No increased toxicity |

| Lapatinib |

Geyer et al. [2006] Cameron et al. [2010] |

III | 324 | Lapatinib+capecitabine versus capecitabine |

ORR: 22 versus 14% (p = 0.09) TTP: 8.4 versus 4.4 months ( p < 0.001) OS: 8.4 versus 4.1 months (p < 0.001) |

Grade 3/4 events: diarrhea: 13 versus 11% hand-food syndrome: 7 versus 11% nausea: 2 versus 2% vomiting: 2 versus 2% |

| Pertuzumab | Baselga et al. [2010] | II | 66 | Pertuzumab+ trastuzumab | ORR: 24.2% CBR: 50% PFS: 5.5 months |

Grade 3 events: diarrhea: 2 patients central line infection: 1 patient rash: 1 patient |

| T-DM1 | EMILIA- Verma et al. [2012] |

III | 991 | T-DM1 versus lapatinib+capecitabine |

PFS: 9.6 versus 6.4 months (p < 0.001) OS: 30.9 versus 25.1 months (p < 0.001) ORR: 43.6 versus 30.8% (p < 0.001) |

Grade 3/4 events: 41 vs. 57% grade 3/4 events: thrombocytopenia, 12.9 versus 0.2% elevated AST: 4.3 versus 0.8% diarrhea, 1.6 versus 20.7% nausea, 0.8 versus 2.5% vomiting, 0.8 versus 2.5% hand foot syndrome, 0 versus 16.4% severe hemorrhage: 1.4% versus 0.8% |

| Third-line and beyond | ||||||

| Lapatinib | EGF104900- Blackwell et al.[2010, 2012] |

III | 296 | Lapatinib+trastuzumab versus trastuzumab |

PFS:12.1versus 8.1weeks(p= 0.008) OS: 14 versus 9.5 months (p= 0.026) ORR: 10.3 versus 6.9% (p = 0.46) CBR: 24.7 versus 12.4% (p = 0.01) |

Asympomatic cardiac events: 3.4 versus 1.4% Symptomatic cardiac events: 2 versus 0.7% |

| T-DM 1 | TH3RESA- Krop et al. [2014] |

III | 602 | T-DM1 versus physician’s choice | PFS: 6.2 versus 3.3 months (p < 0.001) interim OS: a trend favoring T-DM1 (p = 0.0034) ORR: 31 versus 9% (p <0·0001) |

Grade 3/4 events: 32.3 versus 43.5% grade 3/4 events: thrombocytopenia, 5 versus 2% hemorrhage, 2 versus <1% neutropenia, 2 versus 16% diarrhoea, <1% versus 4% febrile neutropenia, <1 versus 4% |

| CNS metastases | ||||||

| Untreated brain metastases | ||||||

| Lapatinib | LANDSCAPE- Bachelot et al. [2013] |

II | 45 | Lapatinib+ capecitabine | CNS ORR : 65.9% TTP: 5.5 months |

Grade 3/4 events: diarrhoea: 20% hand-foot syndrome: 20% |

| T-DM1 | EMILIA subanalysis- Krop, et al. [2015] |

III | 95 with CNS metastases | T-DM1 versus. lapatinib+ capecitabine |

PFS: 5.9 versus 5.7 months (p = 1.000) OS: 26.8 versus 12.9 months (p = 0.008) |

Grade 3/4 events: 48.8% versus 63.3% |

| Treated brain metastases | ||||||

| Lapatinib | EGF105084- Lin et al.[2009] |

II | 242 | Lapatinib | CNS ORR:6% | Diarrhoea: 65% rash:30% nausea; 26% vomitifng: 24% |

| Sutherland et al. [2010] | IV | 356 | Lapatinib+capecitabine | 34 patients with CNS metastases: ORR 21% TTP 22 weeks |

||

| Prevention of CNS metastases. | ||||||

| Lapatinib | CEREBEL (EGF111438)- Pivot et al. [2015]. |

III | 540 | Lapatinib + capecitabine versus trastuzumab + capecitabine |

Incidence of CNS metastases as first site of relapse: 3 versus 5% PFS: 6.6 versus 8.1 months (HR:1.30, 95% CI 1.04-1.64) OS: 22.7versus 27.3 months (HR: 1.34, 95% CI 0.95-1.64) |

Grade 3/4 events: 13 versus 17% |

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HER2+, HER2 positive; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; CNS, central nervous system; CBR, clinical benefit rate; ORR, objective response rate; PR, partial response; TTP, time to progression; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival. AST, aspirate aminotransferase. A, doxorubicin; E, epirubicin; C, cyclophosphamide; T-DM1, Ado-trastuzumab emtansine,; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Lapatinib

Lapatinib is an oral, dual, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) of both HER2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). In the pivotal phase III trial, women with HER2+ advanced breast cancer who had progressed after trastuzumab-based treatment were randomly assigned to receive either lapatinib plus capecitabine or capecitabine alone. The addition of lapatinib to capecitabine significantly improved median TTP compared with capecitabine alone (8.4 versus 4.4 months, p < 0.001) [Geyer et al. 2006]. The final updated survival analysis performed when 83% patients had died showed a trend toward improved median survival with lapatinib plus capecitabine (75.0 weeks) compared with capecitabine alone (64.7 weeks) [hazard ratio (HR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71–1.08 p = 0.210]. A Cox regression analysis considering crossover as a time-dependent covariate demonstrated that there may have been a 20% lower risk for death for patients in the combination therapy arm (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64–0.99 p = 0.043) [Cameron et al. 2010]. Based on the initial TTP results, lapatinib was approved by the FDA in 2007 in combination with capecitabine for the treatment of patients with HER2+ MBC whose disease progressed while receiving trastuzumab-based chemotherapy.

Based on preclinical studies demonstrating synergy and lack of cross-resistance between lapatinib and trastuzumab [Konecny et al. 2006], the EGF104900 study compared the efficacy and safety of lapatinib alone with lapatinib and trastuzumab in patients with HER2+ MBC progressing on prior trastuzumab-based therapy [Blackwell et al. 2010]. In 296 patients who received a median of 3 prior trastuzumab-containing regimens, the combination of lapatinib with trastuzumab was superior to lapatinib alone for progression-free survival (PFS) (12.1 versus 8.1 weeks, p = 0.008) and CBR (24.7% versus 12.4%, p = 0.01). Longer follow up demonstrated a significant 4.5 month improvement in OS with the combination therapy [Blackwell et al. 2012]. The most frequent adverse events were diarrhea, rash, nausea and fatigue. Only diarrhea was higher in the combination group (60% versus 48%, p = 0.03), while the incidence of grade 3 or higher diarrhea was similar for both groups (7%). These data support the use of dual HER2 blockade in patients with heavily pretreated HER2+ MBC, which is a useful nonchemotherapy treatment strategy in this setting.

In the first-line setting, the phase III CTG MA.31 trial compared the efficacy of taxane plus either trastuzumab or lapatinib as treatment for HER2+ MBC. The median PFS in the lapatinib group was significantly shorter than that seen in those receiving trastuzumab (9.1 versus 13.6 months, HR 1.48, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was more grade 3 or 4 diarrhea and rash in the lapatinib group (p < 0.001) and poorer compliance with HER2 targeted therapy [Gelmon et al. 2015]. Overlapping toxicity led to reduced drug exposure in the lapatinib group, perhaps contributing to its inferior efficacy in combination with taxanes compared with trastuzumab.

Lapatinib appears to have some degree of activity in the treatment of HER2+ brain metastases. In patients with progressive brain metastases after radiotherapy, the response rate to single-agent lapatinib is only 6% [Lin et al. 2009]. However, this increases to 21–31.8% when given in combination with capecitabine [Sutherland et al. 2010; Metro et al. 2011]. In HER2+ patients with previously untreated brain metastases, a single-arm multicenter phase II study of lapatinib plus capecitabine conducted in France reported a central nervous system (CNS) ORR of 65.9%, TTP of 5.5 months and OS of 17.0 months [Bachelot et al. 2013]. The phase III CEREBEL (EGF111438) study was designed to compare development of CNS metastases in patients with HER2+ MBC without baseline CNS metastases treated with capecitabine plus either lapatinib or trastuzumab. This study was terminated after an interim analysis including 475 randomly assigned patients, with no difference in the incidence of new CNS metastases between the 2 arms (capecitabine–lapatinib: 3%; capecitabine–trastuzumab: 5%). PFS and OS were longer with trastuzumab (HR for PFS 1.30, 95% CI 1.04–1.64; HR for OS 1.34, 95% CI 0.95–1.64) [Pivot et al. 2015] (Table 1).

Pertuzumab

Pertuzumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to a different epitope of the HER2 extracellular domain (subdomain II) than trastuzumab (subdomain IV), thereby preventing HER2 from dimerizing with other members of the HER family (EGFR, HER3 and HER4), most notably HER3. It is the first in a new class of agents that inhibit dimerization of the HER receptors [Agus et al. 2002; Franklin et al. 2004]. The combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab provide a more comprehensive blockade of the HER2 signaling pathway, resulting in strongly enhanced antitumor activity compared with either agent alone in HER2+ tumor models [Scheuer et al. 2009].

A phase II trial evaluated pertuzumab alone or pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab in patients with disease progressing on trastuzumab/chemotherapy combinations. Although pertuzumab alone had very little antitumor activity, the combination therapy resulted in a CBR of 50% and an ORR of 24.2%. PFS was 5.5 months with minimal additional toxicity from the addition of pertuzumab [Baselga et al. 2010].

In 2012, results from the Clinical Evaluation of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab (CLEOPATRA) phase III study led to FDA approval for pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel for the treatment of patients with HER2+ MBC who have not received prior anti-HER2 or chemotherapy for metastatic disease. The CLEOPATRA trial randomized 808 patients from 204 centers in 25 countries with treatment naïve HER2+ MBC to receive trastuzumab plus docetaxel with pertuzumab or placebo. Trastuzumab and either pertuzumab or placebo was continued after discontinuation of chemotherapy in responding patients until tumor progression or death. It is interesting to note that approximately one-half of the patients in this study had received no prior adjuvant chemotherapy and only 10% had received prior adjuvant trastuzumab. The median number of cycles of docetaxel per patient was 8 in both the control group (range: 1–41) and in the pertuzumab group (range: 1–35). The primary endpoint of centrally confirmed PFS was significantly longer with the addition of pertuzumab, improving by 6.3 months from a median of 12.4 to 18.5 months (HR for progression or death 0.62, 95% CI 0.51–0.75 p < 0.001) [Baselga et al. 2012]. Final OS analysis showed that OS was markedly prolonged for 15.7 months, with the addition of pertuzumab extending OS from 40.8 to 56.5 months (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.56–0.84 p < 0.001) [Swain et al. 2015]. Pertuzumab was generally well tolerated, with the primary toxicities including an increased rate of diarrhea (all grade: 68.4% versus 48.7%; grade ⩾3: 9.3% versus 5.1%), rash (37.5% versus 24%), mucosal inflammation (27.8% versus 19.9%), febrile neutropenia (13.8% versus 7.6%) and dry skin (10.6% versus 4.3%). Of note, there was no difference in left ventricular systolic dysfunction [Baselga et al. 2012]. Headache, upper respiratory tract infection and muscle spasm were also reported higher in the pertuzumab group [Swain et al. 2015]. In the CLEOPATRA trial, the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab and docetaxel had no adverse impact on health-related quality-of-life and prolonged time to worsening of breast cancer-specific symptoms [Cortés et al. 2013].

Based on the CLEOPATRA data, pertuzumab is now widely approved in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel for first-line treatment of patients with HER2+ MBC in many countries, including the USA, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, European Union and South Africa. Starting from version 2.2012, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast Cancer Guideline has listed pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab and a taxane (either docetaxel or paclitaxel) as preferred first- or second-line therapy for the treatment of HER2+ MBC. The 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) clinical practice guideline recommends trastuzumab, pertuzumab and a taxane for first-line treatment of patients with HER2+ advanced breast cancer [Giordano et al. 2014]. Based on CLEOPATRA, it is reasonable to treat with the triple drug combination until best clinical response, and then continue with double antibodies alone as maintenance.

There is significant interest in identifying biomarkers that will predict those whose tumors will be most likely to respond to pertuzumab in combination with standard HER2 targeted therapy. A biomarker analysis of tumor samples from patients enrolled in the CLEOPATRA trial identified prognostic, but not predictive markers, similar to prior studies. High HER2 protein, high HER2 and HER3 mRNA levels, wildtype PIK3CA and low serum HER2 extracellular domain (sHER2) were associated with a significantly better prognosis (p < 0.05). Patients with wildtype PIK3CA had a longer median PFS than those with mutant PIK3CA in both the control (13.8 versus 8.6 months) and pertuzumab groups (21.8 versus 12.5 months). The addition of pertuzumab provided a similar relative improvement in outcome regardless of PIK3CA status [Baselga et al. 2014].

Additional combinations have been studied. A phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel combined with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in 69 patients demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability [Dang et al. 2015]. The VELVET study treated 213 patients with vinorelbine, pertuzumab and trastuzumab in the first-line setting and reported a response rate of 62.9% but a PFS of only 14.3 months [Andersson et al. 2014]. Ongoing trials are evaluating novel pertuzumab/trastuzumab and chemotherapy combination including eribulin mesylate [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01912963], gemcitabine [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02252887] and capecitabine [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01026142] as either first- or second-line therapy as an appropriate option for HER2+ MBC.

Due to the known prediction of HER2+ disease for the brain, the incidence and time to development of CNS metastases in the CLEOPATRA trial was analyzed [Swain et al. 2014]. The incidence of CNS metastases as first site of disease progression was similar between the pertuzumab group and the control group (13.7% versus 12.66%). However, median time to development of CNS metastases as the first site of disease progression was prolonged in the pertuzumab group (15.0 months) compared with the control group (11.9 months) (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39–0.85 p = 0.0049). OS in patients who developed CNS metastases as the first site of disease progression showed a trend in favor of the pertuzuamb group (34.4 versus 26.4 months), although this difference was not significant (Table 1).

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1)

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) is a novel antibody drug conjugate composed of trastuzumab linked to emtansine (DM1; a derivative of maytansine), a highly potent antimicrotubule cytotoxic agent, through a nonrededucible thioether linkage [succinimidyl 4-(N-maleimidomethyl)-cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (SMCC)]. An average of 3.5 DM1 molecules are carried per 1 molecule of trastuzumab [Lewis Phillips et al. 2008], allowing intracellular drug delivery specifically to HER2 overexpressing cells. This approach offers the potential to improve the therapeutic index while at the same time minimizing exposure of normal tissue to the cytotoxic agent. T-DM1 was granted FDA approval in 2013 for HER2+ MBC that has progressed after trastuzumab and taxane therapy in the metastatic setting or following early relapse on adjuvant trastuzumab-based therapy. Approval was based on data from the EMILIA trial [Verma et al. 2012], a randomized, open-label, international phase III trial comparing T-DM1 with lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with HER2+ MBC previously treated with trastuzumab and a taxane. The primary endpoints were PFS assessed by independent review, OS and safety. A total of 991 patients were randomized at 213 centers in 26 countries to receive T-DM1 or lapatinib plus capecitabine. Independently reviewed median PFS was significantly prolonged with T-DM1 compared with lapatinib plus capecitabine (9.6 versus 6.4 months; HR for progression or death from any cause 0.65, 95% CI 0.55–0.75 p < 0.001). Median OS was also significantly improved with T-DM1 (30.9 versus 25.1 months; HR for death from any cause 0.68, 95% CI 0.55–0.85, p < 0.001) and ORR was higher with T-DM1 (43.6% versus 30.8%, p < 0.001).

In addition to improving efficacy, treatment with T-DM1 was associated with lower overall toxicity. Rates of adverse events of ⩾ grade 3 were more frequent with lapatinib plus capecitabine than with T-DM1 (57% versus 41%). The most commonly grade 3 or worse adverse events with T-DM1 were thrombocytopenia (12.9%) and elevated serum concentration of aspirate aminotransferase (4.3%) and alanine aminotransferase (2.9%). The overall incidence of hemorrhage was higher with T-DM1 (29.8% versus 15.8%), while rates of severe hemorrhage was low in both arms (1.4% and 0.8%, respectively) [Verma et al. 2012]. Based on these data, T-DM1 is now the standard of care as second-line therapy for HER2+ MBC.

A second randomized, open-label, international phase III trial provides additional supportive data for T-DM1. The TH3RESA trial randomized 602 patients with HER2+ MBC in a 2:1 ratio to receive T-DM1 or treatment of the physician’s choice. Eligibility included evidence of progressive disease following two or more HER2-directed regimens for MBC. Patients in the control arm were allowed to crossover to T-DM1 on progression. More than half of the patients had received four previous lines of therapy (excluding single-agent hormonal therapy) for MBC and nearly one-third had received greater than five previous lines of treatment. Median PFS was longer in patients treated with T-DM1 compared with physician’s choice (6.2 versus 3.3 months; HR 0.528, p < 0.001) and the interim median OS showed a trend favoring T-DM1 (HR 0.552, p = 0.0034, efficacy stopping boundary not crossed). Safety results were similar to EMILIA with more grade 3 or worse adverse events in the control than in the T-DM1 arm (43.5% versus 32.3%), although there was a higher (although low overall) rate of severe thrombocytopenia (5% versus 2%) and hemorrhage (2% versus <1%) in patients treated with T-DM1. Cardiac events were low in both groups and were not significantly different [Krop et al. 2014]. This study confirmed that T-DM1 provides a clinically significant benefit for patients with HER2+ MBC progressing on both trastuzumab and lapatinib, as well as on prior chemotherapy.

Combined data suggest that T-DM1 may have less cardiac toxicity compared with trastuzumab, but it is important to keep in mind that all patients receiving T-DM1 in current analyses had already received trastuzumab without resulting reduction in cardiac function, resulting in significant preselection bias. An integrated safety analysis of 884 T-DM1 exposed patients, combining available data from all single-agent T-DM1 studies to date, found low rates of cardiotoxicity, with decline in postbaseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) to less than 40% in only 0.5%, and LVEF decline of ⩾15% from baseline to below 50% in 1.8%. Cardiac toxicity resulted in discontinuation of T-DM1 in 0.45% of patients [Dieras et al. 2014].

Although T-DM1 is currently approved only in patients with previously treated HER2+ MBC, early data suggest potential efficacy in the first-line setting. A randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase II study compared T-DM1 with trastuzumab plus docetaxel as first-line treatment of 137 patients with HER2+ MBC (TDM4450g) [Hurvitz et al. 2013]. Treatment with T-DM1 resulted in a significant improvement in PFS over trastuzumab plus docetaxel (14.2 versus 9.2 months; HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36–0.97 p = 0.037), and ORR was modestly improved at 64.2% with T-DM1 compared with 58.0% with trastuzumab plus docetaxel. Again, T-DM1 is associated with fewer grade 3 adverse events (46.4% versus 90.9%) as well as adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (7.2% versus 40.9%).

In cell culture and mouse xenograft models of HER2 amplified cancer, dual targeting of HER2 with the combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab has showed synergistic inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptotic cell death [Phillips et al. 2014]. To study this effect, the randomized, multicenter, phase III MARIANNE study [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01120184] [Ellis et al. 2011] randomized 1095 women with HER2+ MBC without prior chemotherapy in the advanced setting to receive either trastuzumab plus docetaxel or paclitaxel, T-DM1 with pertuzumab or T-DM1 with pertuzumab–placebo. The primary endpoint was PFS by central review. Unlike CLEOPATRA, in MARIANNE 31% of patients had received HER2 targeted therapy in the adjuvant setting. PFS was similar between the 3 arms, demonstrating noninferiority of each experimental therapy (13.7 versus 15.2 versus 14.1 months for trastuzumab/taxane, T-DM1/pertuzumab and T-DM1/placebo, respectively) [Ellis et al. 2015]. OS data are still immature. Toxicities such as neutropenia and alopecia were higher in the patients receiving taxanes, as expected. It is quite intriguing that the addition of pertuzumab to T-DM1 was not superior to either T-DM1 alone or the trastuzumab/taxane doublet, given the marked benefit of pertuzumab in CLEOPATRA. It may be that the beneficial interaction of pertuzumab is dependent on interactions with free trastuzumab and taxanes. Ongoing trials are studying the combination of T-DM1 and pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, so more data will be forthcoming.

T-DM1 appears to have some activity against CNS metastases. The EMILIA trial reported improved OS in 45 patients with CNS metastases at baseline receiving T-DM1 compared with 50 patients receiving lapatinib and capecitabine (26.8 versus 12.9 months; HR 0.38, p = 0.008) [Krop et al. 2015]. Two case series also documented response in CNS metastases in patients receiving T-DM1 [Bartsch et al. 2014; Torre et al. 2015] (Table 1).

Novel targeted agents for HER2+ MBC

Everolimus

Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway is an important mechanism of resistance to trastuzumab [Berns et al. 2007]; the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a major downstream effector of this pathway. Everolimus is an oral mTOR inhibitor blocking the PI3K pathway. Preclinical studies demonstrated that the combination of everolimus and trastuzumab rescued phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) loss-induced trastuzumab resistance and slowed the growth of HER2+ breast cancer cells [Lu et al. 2007].

Two phase III trials have evaluated everolimus in the treatment of HER2+ MBC in combination with trastuzumab. BOLERO-3 randomized 569 women with HER2+ MBC resistant to trastuzumab to receive everolimus (5 mg/day) or placebo plus weekly trastuzumab and vinorelbine, with a primary endpoint of PFS [André et al. 2014]. Trastuzumab resistance was defined as recurrence during or within 12 months of adjuvant treatment or progression during or within 4 weeks of treatment for advanced disease. PFS was modestly longer in the everolimus group than those receiving placebo (7 versus 5.78 months; HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.65–0.95 p = 0.0067). Subgroup analyses of PFS showed that patients with estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative breast cancer, patients with nonvisceral metastases, younger patients (aged <65 years) and those who had received adjuvant or neoadjuvant trastuzumab appeared to derive more benefit from the everolimus combination. OS has not yet been reported and ORR was similar between the two arms (41% versus 37%, 95% CI 31.6–43.1 p = 0.2108). Treatment with everolimus resulted in significantly increased toxicity. The most common grade 3–4 adverse events were neutropenia (73% in the everolimus group versus 62% in the placebo group), anemia (19% versus 6%), febrile neutropenia (16% versus 4%), stomatitis (13% versus 1%) and fatigue (12% versus 4%).

Biomarkers were analyzed on archival tumor and included PTEN, the 40S ribosomal protein S6 (pS6), and PIK3CA from 237 (42%), 188 (33%) and 182 (32%) patients, respectively. Exploratory analysis showed greater benefit derived from the addition of everolimus in patients with a low PTEN concentration than in those with a high PTEN concentration (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20–0.82 pinteraction = 0.01) and in patients with a high pS6 concentration than in those with low pS6 concentration (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24–0.96 pinteraction = 0.04). PIK3CA mutations did not seem to predict benefit (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.21–1.45 pinteraction = 0.32). Based on the minimal increase in PFS and the increase in toxicity, this treatment is not recommended and more work on biomarkers is clearly needed.

Everolimus was evaluated as first-line therapy for HER2+ MBC in the BOLERO-1/TRIO 019 trial, that randomized 719 patients with treatment naïve HER2+ MBC in a 2:1 ratio to receive trastuzumab and paclitaxel in combination with everolimus (n = 480) or placebo (n = 239). Of note, the dose of everolimus was 10 mg, twice which of BOLERO-3 and the FDA approved dose in combination with hormone therapy. Results were presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium [Hurvitz et al. 2014]. The addition of everolimus did not improve PFS in the entire population (14.95 versus 14.49 months, HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.73–1.08 p = 0.1166), and although PFS was prolonged by 7 months in the hormone receptor-negative subpopulation (20.27 versus 12.88 months, HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.91 p = 0.0049), this not meet the protocol prespecified statistical significance threshold. The safety profile was consistent with results previously reported in BOLERO-3.

Based on these combined data, everolimus does not have a current therapeutic role in the treatment of HER2+ breast cancer. In addition to everolimus, there are several PI3K inhibitors that are currently under investigation as treatment for HER2+ MBC. BYL719, an alpha-specific PI3K inhibitor, is being studied in combination with T-DM1 in a phase I study in patients with HER2+ MBC with progressive disease following trastuzumab and taxane-based therapy [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02038010]. Taselisib (GDC-0032), a selective inhibitor of mutant PI3K alpha is being evaluated in a phase Ib trial in combination with T-DM1, T-DM1 plus pertuzumab, trastuzumab plus pertuzumab, and trastuzumab, pertuzumab and paclitaxel in patients with HER2+ MBC [Clinical Trials.gov identi-fier: NCT02390427]. Pilaralisib (SAR245408), a pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, was tested in combination with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in a phase I/II study, demonstrating acceptable safety with early evidence of clinical activity in trastuzumab-refractory HER2+ MBC [Tolaney et al. 2015] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of completed and ongoing clinical trials of novel targeted agents for HER2+ MBC.

| Agent | Study | Phase | Patient population | Number of patients | Treatment regimen | outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everolimus | BOLERO-3- André et al. [2014] |

III | Second-line | 569 | Everolimus+trastuzumab+vinorelbine versus trastuzumab+vinorelbine |

PFS: 7 versus 5.78 months (p = 0.0067) ORR: 41 versus 37% (p = 0.2108) |

| BOLERO-1/TRIO 019 Hurvitz et al. [2014] |

III | First-line | 719 | Everolimus+trastuzumab+paclitaxel versus trastuzumab+paclitaxel |

PFS: 14.95 versus 14.49 months ( p = 0.1166) PFS in HR-subpopulation: 20.27 versus 12.88 months (p = 0.0049) |

|

| BYL 719 | [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:NCT02038010] | I | Second-line and beyond | 28 | BYL 719 + T- DM1 | Ongoing |

| Taselisib ( GDC-0032) | [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02390427] | Ib | No limit | 76 | Arm1: taselisib + T-DM1 Arm 2: taselisib+ T-DM1 + pertuzumab Arm 3: taselisib + trastuzumab + pertuzumab Arm4: taselisib + pertuzumab + trastuzumab + paclitaxel |

Ongoing |

| Pilaralisib (SAR245408) |

Tolaney et al. [2015] | I/II | Second-line and beyond | 43 | Pilaralisib + trastuzumab versus pilaralisib + trastuzumab + paclitaxel |

Treatment-related adverse events: diarrhea: 23.8 versus 66.7% fatigue: 14.3 versus 42.9% rash: 33.3 versus 38.1% |

| MM-302 | HERMION [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02213744] |

II | Second-line | 250 | MM-302 + trastuzumab versus

Chemotherapy of physician’s choice+ trastuzumab |

Ongoing |

| Margetuximab(MGAH22) | [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01828021] Burris et al. [2015] |

II | Third-line and beyond |

41 | Margetuximab | Ongoing 19 evaluable patients: PR: 5/19 (21%) PFS: 169 days |

| ONT-380 (ARRY-380) |

[ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01983501] Borges et al. [2015] |

Ib | Second-line and beyond | 63 | ONT-380 + T-DM1 | Ongoing |

| [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02025192] Hamilton et al. [2015] |

Ib | Third-line and beyond |

138 | ONT-380 + capecitabine versus ONT-380 + trastuzumab versus ONT-380 + capecitabine + trastuzumab |

Ongoing | |

| Neratinib (HKI-272) | Martin et al. [2013] | II | Third-line and beyond |

233 | Neratinib versus lapatinib + capecitabine |

ORR: 29% versus 41% (p = 0.067) PFS: 4.5 versus 6.8 months (p = 0.231) OS: 19.7 versus 23.6 months (p = 0.280) |

| Saura et al. [2014] | I/II | Second-line and beyond | 72 | Neratinib + capecitabine | ORR:64% in lapatinib-naïve patients and 57% in patients previously treated with lapatinib PFS: 40.3 and 35.9 weeks, respectively |

|

| Jankowitz et al. [2013] | I | Second-line and beyond | 21 | Neratinib +weekly paclitaxel +trastuzumab | ORR: 38% CBR: 52% PFS: 3.7 months |

|

| NALA [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01808573] |

III | Third-line and beyond |

600 | Neratinib+capecitabine versus Lapatinib+capecitabine |

Ongoing | |

| NEfERTT [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00915018] |

II | First-line | 479 | Neratinib+paclitaxel versus trastuzumab+paclitaxel |

Ongoing | |

| [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01494662] |

II | Brain metastases | 105 | Neratinib versus Neratinib+capecitabine |

Ongoing | |

| Afatinib (BIBW 2992) |

Lin et al. [2012] | II | Second-line | 41 | Afatinib | CBR:46% PFS: 15.2 months OS: 61 weeks |

| LUX-Breast 1 - Harbeck et al. [2014] |

III | First or Second-line |

508 | Afatinib+vinorelbine versus trastuzumab+vinorelbine |

ORR: 46.1% versus 47% (p = 0.8510) PFS: 5.5 versus 5.6 months ( p = 0.4272) OS: 19.6 versus 28.6 months (p = 0.0036) |

|

| LUX-Breast 3- Cortés et al. [2014] |

II | Second-line and beyond | 121 | Afatinib versus afatinib+vinorelbine versus investigator’s choice of treatment |

CNS ORR: 0 versus 3 versus 6 % PFS: 11.9 versus 12.3 versus 18.4 weeks OS: 57.7 versus 37.3 versus 52.1 weeks |

|

| BMS-754807 | [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00788333] | I/II | Second-line and beyond | 40 | BMS-754807+trastuzumab | Completed, no result report |

| Cixutumumab | [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00684983] | II | Second-line and beyond | 68 | Cixutumumab+lapatinib+capecitabine versus lapatinib+capecitabine |

ongoing |

| Bevacizumab | Martin et al.[2012] | II | First-line | 88 | Bevacizumab+trastuzumab+capecitabine versus trastuzumab+capecitabine |

ORR: 73% PFS: 14.5 months |

| Lin et al. [2013] | II | First-or second-line | 29 | Bevacizumab+trastuzumab+vinorelbine | PFS:9.9 months in the first-line;7.8 months in the second-line. ORR: 73% in the first-line; 71% in the second-line. |

|

| AVEREL- Gianni et al. [2013] |

III | First-line | 424 | Bevacizumab+trastuzumab+docetaxel versus trastuzumab+docetaxel |

PFS:16.5versus 13.7 months ( p = 0.0775) ORR: 74 versus 70% (p = 0.3492) |

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HER2+, HER2 positive; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; ORR, objective response rate; CBR, clinical benefit rate ; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; T-DM1, Ado-trastuzumab emtansine.

MM-302

MM-302 is a nanoliposomal encapsulation of doxorubicin with anti-HER2 antibody fragments attached to its surface to allow for the selective uptake of drug into HER2+ tumor cells while limiting exposure to healthy tissue, such as those of heart. A phase I study documented safety and preliminary antitumor activity of MM-302 in patients with advanced HER2+ breast cancer [Munster et al. 2013]. Based on these encouraging results, the international, open-label, randomized, phase II HERMIONE trial has been initiated to evaluate whether MM-302 plus trastuzumab is more effective than the chemotherapy of physician’s choice plus trastuzumab in anthracycline-naïve patients with HER2+ MBC who have previously received pertuzumab and T-DM1 [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02213744] (Table 2).

Margetuximab

Margetuximab (MGAH22) is a chimeric Fc-engineered monoclonal antibody designed to achieve increased binding to both alleles of CD16A and preservation of the direct antiproliferative activity of trastuzumab. In vitro and in vivo preclinical studies supported the superiority of margetuximab compared with trastuzumab [Nordstrom et al. 2011]. A phase I study showed that margetuximab was well tolerated at all explored doses with antitumor activity in patients with HER2+ MBC who had failed prior trastuzumab and lapatinib [Burris et al. 2013]. Updated data were presented at the ASCO meeting in 2015, with evidence of disease response in patients with HER2+ refractory disease [Burris et al. 2015]. A total of 11 of 19 evaluable patients had tumor reduction, including 5 patients with PR (21%). Median PFS was about 5.5 months and no new safety signals were identified.

A phase III trial, termed SOPHIA and set to open in 2015, will randomize 528 patients with HER2+, trastuzumab, pertuzumab and T-DM1 refractory MBC to receive chemotherapy with trastuzumab or margetuximab. In addition, an ongoing phase II trial is evaluating efficacy of margetuximab in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced breast cancer whose tumors express HER2 at the 2+ level by immunohistochemistry and lack evidence of HER2 gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:NCT01828021] [Pegram et al. 2014] (Table 2).

ONT-380

ONT-380, previously known as ARRY-380, is an orally active, reversible and selective small molecule HER2 inhibitor with nanomolar potency. There are two ongoing phase Ib trials with ONT-380 in patients with HER2+ MBC. The first trial is designed to evaluate ONT-380 in combination with T-DM1 in patients with previously treated with a taxane and trastuzumab [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01983501] [Borges et al. 2015]. The second trial is designed to evaluate ONT-380 in combination with capecitabine and/or trastuzumab in patients previously treated with trastuzumab and T-DM1 [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02025192] [Hamilton et al. 2015a]. Interim analyses from both trials were presented at the ASCO meeting in 2015 [Ferrario et al. 2015; Hamilton et al. 2015b]. In patients with response-evaluable CNS metastases, ONT-380 demonstrated promising activity in both the CNS and other systemic sites in combination with either T-DM1, trastuzumab and/or capecitabine. Responses were seen in a small number of patients with heavily pretreated MBC receiving ONT-380 in combination (Table 2).

Neratinib

Neratinib (HKI-272) is a potent, irreversible pan-TKI of HER1, HER2 and HER4, with antitumor activity and acceptable tolerability in patients with HER2 resistant disease [Rabindran et al. 2004; Burstein et al. 2010]. Preclinical data have demonstrated that neratinib has the potential to overcome trastuzumab resistance in HER2 amplified breast cancer [Canonici et al. 2013]. A phase II trial assessed the non-inferiority of neratinib monotherapy in comparison with lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with HER2+ MBC who had received no more than 2 prior trastuzumab regimens, demonstrating lack of superiority with neratinib (HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.89–1.60), with PFS (4.5 versus 6.8 months), OS (19.7 versus 23.6 months) and ORR (29% versus 41%) for the comparison of neratinib to lapatinib and capecitabine [Martin et al. 2013].

Subsequently, a multinational, open-label, phase I/II study evaluated the safety and efficacy of neratinib in combination with capecitabine in patients with trastuzumab-pretreated HER2+ MBC. The ORR was 64% in lapatinib-naïve patients and 57% in patients previously treated with lapatinib, with PFS of 40.3 and 35.9 weeks, respectively. The most common toxicities were diarrhea (88%), and hand-foot syndrome (48%) [Saura et al. 2014]. In another phase I study, neratinib in combination with weekly paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with HER2+ MBC previously treated with anti-HER agent(s) and a taxane resulted in an ORR 38%, CBR 52%, with a PFS of 3.7 months [Jankowitz et al. 2013].

In the first-line setting, 479 patients with HER2+ MBC were randomized in an international phase II trial to receive either neratinib plus paclitaxel or trastuzumab plus paclitaxel (NEfERTT trial) [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00915018]. The results were the subject of a press release on 13 November 2014, reporting similar PFS between the two treatment arms but less brain metastases in those treated with neratinib versus trastuzumab (7.4 versus 15.6%, p = 0.006). Toxicity was increased with neratinib, with 40% grade 3 diarrhea compared with 4% with paclitaxel although no prophylactic antidiarrheal therapy was used. Data are expected to be presented at a meeting in the near future. Other trials have reported a marked reduction in diarrhea with prophylactic antidiarrheal therapy; this strategy is being employed in current studies.

The ongoing phase III NALA study is randomizing patients with HER2+ MBC who have received two or more prior HER2 directed regimens in the metastatic setting to neratinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01808573]. This study has an estimated enrollment of 600 patients. Additionally, a phase II study of neratinib for HER2+ MBC with brain metastases is currently recruiting patients [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01494662] (Table 2).

Afatinib

Afatinib (BIBW 2992) is a novel, orally, bioavailable, irreversible, small molecule pan-HER inhibitor undergoing clinical investigation in HER2-resistant MBC. A phase II study treated patients with HER2+ MBC that had progressed on trastuzumab with afatinib and reported a CBR 46% (19/41) with PFS of 15.1 months (95% CI 8.1–16.7) and OS of 61 weeks (95% CI 56.7 to not evaluable) [Lin et al. 2012]. The phase III LUX-Breast 1 trial, assessing afatinib plus vinorelbine versus trastuzumab plus vinorelbine in patients with HER2+ MBC after failure of prior trastuzumab-based regimen, showed similar PFS (5.5 versus 5.6 months, HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.86–1.4 p = 0.4272) and ORR (46.1% versus 47%), but shorter OS in the afatinib arm (19.6 versus 28.6 months, HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.20–2.59 p = 0.0036) [Harbeck et al. 2014]. Similarly, LUX-Breast 3, a randomized phase II trial comparing afatinib monotherapy or plus vinorelbine with investigator choice of treatment in patients with HER2+ MBC progressing with brain metastases after trastuzumab- or lapatinib-based therapy, also showed no benefit for afatinib-containing regimens over treatments selected by the investigator [Cortés et al. 2014] (Table 2). Based on these negative trials, afatinib is unlikely to be approved for the treatment of HER2+ breast cancer.

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) inhibitors

In breast cancer cell models that overexpress HER2/neu, IGF1R overexpression led to trastuzumab resistance [Lu et al. 2001]. Preclinical studies showed that an IGF1R inhibitor, I-OMe-AG538, increased sensitivity of trastuzumab-resistant cells to trastuzumab [Nahta et al. 2005]. A phase I/II trial of BMS-754807, an IGF1R inhibitor, in combination with trastuzumab in patients with HER2+ MBC has been completed [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00788333]. The results of this study have not yet been presented. Cixutumumab, another IGF1R inhibitor, is being tested in a phase II trial with capecitabine and lapatinib in patients with previously treated HER2+ MBC [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00684983] (Table 2).

Bevacizumab

Angiogenesis is essential for cancer growth, invasion and metastasis. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a key role in angiogenesis and tumor growth [Leung et al. 1989; Hicklin and Lin, 2005] and HER2 overexpression is associated with upregulation of VEGF [Yen et al. 2000; Konecny et al. 2004]. Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that recognizes and binds to all isoforms of VEGF, inhibiting tumor-related angiogenesis [Rugo, 2004]. In a small open-label phase II trial (n = 88), the combination of bevacizumab, trastuzumab and capecitabine resulted in an ORR of 73% (95% CI 62–82%) and a median PFS of 14.4 months [Martin et al. 2012]. Another phase II study tested the combination of bevacizumab, trastuzumab and vinorelbine in patients with first- or second-line HER2+ MBC, but was closed early due to higher than expected rates of grade 3 and 4 nonhematologic toxicities [Lin et al. 2013]. The AVEREL trial was a phase III trial that randomized patients with HER2+ MBC to receive trastuzumab and docetaxel, with or without bevacizumab in the first-line setting. Investigator-assessed PFS was almost 3 months longer in the bevacizumab, trastuzumab and docetaxel (BTH) arm compared with trastuzumab and docetaxel (TH) (16.5 versus. 13.7 months), but this difference was not statistically significant (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.65–1.02 p = 0.0775) [Gianni et al. 2013] (Table 2). The toxicity of bevacizumab, paired with apparent lower efficacy compared with pertuzumab as well as lack of improved outcome in the adjuvant setting [Slamon et al. 2013], have essentially eliminated bevacizumab as a viable treatment for HER2+ breast cancer.

Current therapeutic options

HER2 is a validated therapeutic target that remains relevant throughout the disease process. The available clinical trials demonstrate that patients with HER2+ MBC can be treatment safely with a variety of systemic HER2 directed therapies and survival rates are improving markedly. So far, the FDA has approved four HER2-targeted agents including trastuzumab, pertuzumab, lapatinib and T-DM1 for patients with HER2+ MBC. The latest results of important clinical trials supporting use of these agents in the treatment of HER2+ MBC has totally changed therapeutic options in clinical practice (Table 1).

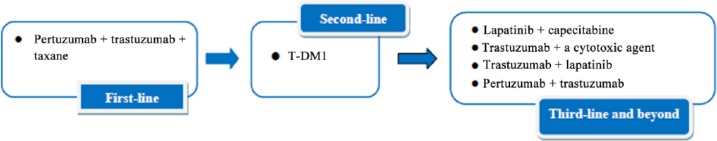

In general, the optimal sequence of therapies for HER2+ MBC should be as follows. In the first- or second-line setting, pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with taxane chemotherapy has replaced trastuzumab and taxane as the treatment of choice. Patients should be treated with the triple drug combination until best clinical response, and then continue with the double antibodies as maintenance therapy. Patients initially treated with an alternative chemotherapy regimen, such as capecitabine, should be offered pertuzumab, trastuzumab and a taxane in the second-line setting due to the significant survival advantage demonstrated in CLEOPATRA, although in general, we recommend pertuzumab in the first-line setting. In the second or greater-line setting, or for patients relapsing within 6 months of or while still receiving adjuvant trastuzumab, T-DM1 is the preferred regimen. In the third-line setting and beyond, lapatinib plus capecitabine, trastuzumab in combination with a cytotoxic agent, trastuzumab plus lapatinib, or trastuzumab plus pertuzuamb are also reasonable therapeutic options. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of these options. These approved agents are being actively studied in adjuvant and neoadjuvant trials.

Figure 1.

Sequencing therapeutic options for HER2+ MBC.

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HER2+, HER2 positive; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; T-DM1, ado-trastuzumab emtansine.

In clinical practice, treatment may eventually be customized to specific clinical scenarios, although little data exist at the present time to support this approach. For example, in the first-line setting for patients with HER2+ MBC and CNS metastases, T-DM1 might possibly be a better systemic option. For later line therapy in the setting of CNS metastases, lapatinib plus capecitabine is a reasonable systemic option. However, at the present time, treatment recommendations should be based on outcome data, with therapies offering a survival advantage given first. Following the approval of pertuzumab as neoadjuvant therapy for HER2+ breast cancer, questions have arisen about use of this agent in patients with subsequent relapse. Decisions to use pertuzumab in this setting should be based on duration of exposure in the early stage setting and disease-free interval. Given that approval is currently only in the neoadjuvant setting, a patient with distant relapse at least 6 months after last exposure to pertuzumab could reasonably be considered for dual antibody combination therapy. A more complex issue is how to manage patients whose disease relapses on or shortly after taxanes given for early stage disease. There are limited data with the combination of vinorelbine, trastuzumab and pertuzumab; other combinations are under investigation.

Future directions

Our understanding about the mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance is still limited. The search for biomarkers to predict response and resistance is a critical part of ongoing research. Some studies suggest that the definition of HER2-driven cancers should be expanded to include both rare cases with somatic HER2 activating mutations (without gene amplification) [Bose et al. 2013] and HER2 positivity defined by gene expression. It is still unknown how tumors fitting into a more expanded definition of HER2 positivity will respond to HER2 targeted therapy. New therapeutic directions include a number of promising agents, either alone or in combination, for the treatment of trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ MBC. The overarching goal is to cure more patients with HER2+ breast cancer.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this paper.

Contributor Information

Hanfang Jiang, Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research (Ministry of Education), Department of Breast Oncology, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, Beijing, China.

Hope S. Rugo, University of California San Francisco, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, 1600 Divisadero St, Box 1710 San Francisco CA 94115, USA.

References

- Agus D., Akita R., Fox W., Lewis G., Higgins B., Pisacane P., et al. (2002) Targeting ligand-activated ErbB2 signaling inhibits breast and prostate tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2: 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M., Lopez-Vega J., Petit T., Zamagni C., Freudensprung U., Robb S., et al. (2014) Interim safety and efficacy of pertuzumab, trastuzumab and vinorelbine for first-line (1l) treatment of patients (pts) with HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Ann Oncol 25: iv116–iv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André F., O’Regan R., Ozguroglu M., Toi M., Xu B., Jerusalem G., et al. (2014) Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15: 580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelot T., Romieu G., Campone M., Dieras V., Cropet C., Dalenc F., et al. (2013) Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): a single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 14: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch R., Berghoff A., Preusser M. (2014) Breast cancer brain metastases responding to primary systemic therapy with T-DM1. J Neurooncol 116: 205–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch R., Wenzel C., Altorjai G., Pluschnig U., Rudas M., Mader R., et al. (2007) Capecitabine and trastuzumab in heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 3853–3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J., Cortés J., Im S., Clark E., Ross G., Kiermaier A., et al. (2014) Biomarker analyses in cleopatra: a phase III, placebo-controlled study of pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, first-line metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32: 3753–3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J., Cortés J., Kim S., Im S., Hegg R., Im Y., et al. (2012) Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 366: 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J., Gelmon K., Verma S., Wardley A., Conte P., Miles D., et al. (2010) Phase II trial of pertuzumab and trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab therapy. J Clin Oncol 28: 1138–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns K., Horlings H., Hennessy B., Madiredjo M., Hijmans E., Beelen K., et al. (2007) A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 12: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell K., Burstein H., Storniolo A., Rugo H., Sledge G., Aktan G., et al. (2012) Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 study. J Clin Oncol 30: 2585–2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell K., Burstein H., Storniolo A., Rugo H., Sledge G., Koehler M., et al. (2010) Randomized study of lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28: 1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges V., Hamilton E., Yardley D., Chaves J., Aucoin N., Ferrario C., et al. (2015) A phase 1b study of ONT-380, an oral HER2-specific inhibitor, combined with ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1), in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Cancer Res 32: abstract TPS662. [Google Scholar]

- Bose R., Kavuri S., Searleman A., Shen W., Shen D., Koboldt D., et al. (2013) Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov 3: 224–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris H., Giaccone G., Im S., Bauer T., Oh D., Jones S., et al. (2015) Updated findings of a first-in-human, phase I study of margetuximab (M), an Fc-optimized chimeric monoclonal antibody (MAb), in patients (pts) with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 3 (Suppl.): abstract 523. [Google Scholar]

- Burris H., Giaccone G., Im S., Bauer T., Trepel J., Nordstrom J., et al. (2013) Phase I study of margetuximab (MGAH22), an Fc-modified chimeric monoclonal antibody (MAb), in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors expressing the HER2 oncoprotein. J Clin Oncol 31(Suppl. 15): abstract 3004. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein H., Sun Y., Dirix L., Jiang Z., Paridaens R., Tan A., et al. (2010) Neratinib, an irreversible ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced ErbB2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28: 1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D., Casey M., Oliva C., Newstat B., Imwalle B., Geyer C. (2010) Lapatinib plus capecitabine in women with HER-2-positive advanced breast cancer: final survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. Oncologist 15: 924–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canonici A., Gijsen M., Mullooly M., Bennett R., Bouguern N., Pedersen K., et al. (2013) Neratinib overcomes trastuzumab resistance in HER2 amplified breast cancer. Oncotarget 4: 1592–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés J., Baselga J., Im Y., Im S., Pivot X., Ross G., et al. (2013) Health-related quality-of-life assessment in cleopatra, a phase III study combining pertuzumab with trastuzumab and docetaxel in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 24: 2630–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés J., Dieras V., Ro J., Barriere J., Bachelot T., Hurvitz S., et al. (2014) Randomized phase II trial of afatinib alone or with vinorelbine versus investigator’s choice of treatment in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer with progressive brain metastases after trastuzumab and/or lapatinib-based therapy: Lux-Breast 3. Cancer Res 75: P5–19–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C., Iyengar N., Datko F., D’andrea G., Theodoulou M., Dickler M., et al. (2015) Phase II study of paclitaxel given once per week along with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 33: 442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieras V., Harbeck N., Budd G., Greenson J., Guardino A., Samant M., et al. (2014) Trastuzumab emtansine in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: an integrated safety analysis. J Clin Oncol 32: 2750–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P., Barrios C., Eiermann W., Toi M., Im Y., Conte P., et al. (2015) Phase III, randomized study of trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) ± pertuzumab (P) Vs trastuzumab + taxane (Ht) for first-line treatment of HER2-positive MBC: primary results from the marianne study. J Clin Oncol 33(Suppl): abstract 507. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P., Barrios C., Im Y., Patre M., Branle F., Perez E. (2011) Marianne: a phase III, randomized study of trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) with or without pertuzumab (P) compared with trastuzumab (H) plus taxane for first-line treatment of HER2-positive, progressive, or recurrent locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC). J Clin Oncol 29(Suppl): abstract TPS102. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario C., Welch S., Chaves J., Walker L., Krop I., Hamilton E., et al. (2015) Ont-380 in the treatment of HER2+ breast cancer central nervous system (CNS) metastases (Mets). J Clin Oncol 33(Suppl.): abstract 612. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin M., Carey K., Vajdos F., Leahy D., De Vos A., Sliwkowski M. (2004) Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell 5: 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmon K., Boyle F., Kaufman B., Huntsman D., Manikhas A., Di Leo A., et al. (2015) Lapatinib or trastuzumab plus taxane therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced breast cancer: final results of NCIC CTG MA.31. J Clin Oncol 33: 1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmon K., Mackey J., Verma S., Gertler S., Bangemann N., Klimo P., et al. (2004) Use of trastuzumab beyond disease progression: observations from a retrospective review of case histories. Clin Breast Cancer 5: 52–58; discussion 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer C., Forster J., Lindquist D., Chan S., Romieu C., Pienkowski T., et al. (2006) Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 355: 2733–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni L., Eiermann W., Semiglazov V., Lluch A., Tjulandin S., Zambetti M., et al. (2014) Neoadjuvant and adjuvant trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive locally advanced breast cancer (NOAH): follow-up of a randomised controlled superiority trial with a parallel HER2-negative cohort. Lancet Oncol 15: 640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni L., Romieu G., Lichinitser M., Serrano S., Mansutti M., Pivot X., et al. (2013) Averel: a randomized phase III trial evaluating bevacizumab in combination with docetaxel and trastuzumab as first-line therapy for HER2-positive locally recurrent/metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31: 1719–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano S., Temin S., Kirshner J., Chandarlapaty S., Crews J., Davidson N., et al. (2014) Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 32: 2078–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhirsch A., Gelber R., Piccart-Gebhart M., De Azambuja E., Procter M., Suter T., et al. (2013) 2 years versus 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer (HERA): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 382: 1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton E., Yardley D., Hortobagyi G., Walker L., Borges V., Moulder S. (2015a) A phase 1b study of ONT-380, an oral HER2-specific inhibitor, combined with capecitabine and/or trastuzumab, in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Cancer Res 75: P4–15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton E., Yardley D., Hortobagyi G., Walker L., Borges V., Moulder S. (2015b) Phase 1b study of ONT-380, an oral HER2-specific inhibitor, in combination with capecitabine (C) and trastuzumab (T) in third line + treatment of HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC). J Clin Oncol 33(Suppl.): abstract 602. [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck N., Huang C., Hurvitz S., Yeh D., Shao Z., Im S., et al. (2014) Randomized phase III trial of afatinib plus vinorelbine versus trastuzumab plus vinorelbine in patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer who had progressed on one prior trastuzumab treatment: LUX-breast 1. Cancer Res 75: P5–19–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicklin D., Ellis L. (2005) Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol 23: 1011–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz S., Andre F., Jiang Z., Shao Z., Neciosup S., Mano M., et al. (2014) Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of daily everolimus plus weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel as first-line therapy in women with HER2+ advanced breast cancer: BOLERO-1. Poster presentation, S6–01, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz S., Dirix L., Kocsis J., Bianchi G., Lu J., Vinholes J., et al. (2013) Phase II randomized study of trastuzumab emtansine versus trastuzumab plus docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31: 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowitz R., Abraham J., Tan A., Limentani S., Tierno M., Adamson L., et al. (2013) Safety and efficacy of neratinib in combination with weekly paclitaxel and trastuzumab in women with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer: an NSABP foundation research program phase I study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 72: 1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensuu H., Bono P., Kataja V., Alanko T., Kokko R., Asola R., et al. (2009) Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide with either docetaxel or vinorelbine, with or without trastuzumab, as adjuvant treatments of breast cancer: final results of the FINHER trial. J Clin Oncol 27: 5685–5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konecny G., Meng Y., Untch M., Wang H., Bauerfeind I., Epstein M., et al. (2004) Association between HER-2/neu and vascular endothelial growth factor expression predicts clinical outcome in primary breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 10: 1706–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konecny G., Pegram M., Venkatesan N., Finn R., Yang G., Rahmeh M., et al. (2006) Activity of the dual kinase inhibitor lapatinib (GW572016) against HER-2-overexpressing and trastuzumab-treated breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 66: 1630–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krop I., Kim S., González-Martín A., Lorusso P., Ferrero J., Smitt M., et al. (2014) Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15: 689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krop I., Lin N., Blackwell K., Guardino E., Huober J., Lu M., et al. (2015) Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) versus lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and central nervous system metastases: a retrospective, exploratory analysis in EMILIA. Ann Oncol 26: 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D., Cachianes G., Kuang W., Goeddel D., Ferrara N. (1989) Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 246: 1306–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Phillips G., Li G., Dugger D., Crocker L., Parsons K., Mai E., et al. (2008) Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res 68: 9280–9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N., Dieras V., Paul D., Lossignol D., Christodoulou C., Stemmler H., et al. (2009) Multicenter phase II study of lapatinib in patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15: 1452–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N., Seah D., Gelman R., Desantis S., Mayer E., Isakoff S., et al. (2013) A phase II study of bevacizumab in combination with vinorelbine and trastuzumab in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N., Winer E., Wheatley D., Carey L., Houston S., Mendelson D., et al. (2012) A phase II study of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible Erbb family blocker, in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer progressing after trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133: 1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Wyszomierski S., Tseng L., Sun M., Lan K., Neal C., et al. (2007) Preclinical testing of clinically applicable strategies for overcoming trastuzumab resistance caused by PTEN deficiency. Clin Cancer Res 13: 5883–5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Zi X., Zhao Y., Mascarenhas D., Pollak M. (2001) Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin). J Natl Cancer Inst 93: 1852–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Bonneterre J., Geyer C., Jr., Ito Y., Ro J., Lang I., et al. (2013) A phase two randomised trial of neratinib monotherapy versus lapatinib plus capecitabine combination therapy in patients with HER2+ advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 49: 3763–3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Makhson A., Gligorov J., Lichinitser M., Lluch A., Semiglazov V., et al. (2012) Phase II study of bevacizumab in combination with trastuzumab and capecitabine as first-line treatment for HER-2-positive locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 17: 469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty M., Cognetti F., Maraninchi D., Snyder R., Mauriac L., Tubiana-Hulin M., et al. (2005) Randomized phase II trial of the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab combined with docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer administered as first-line treatment: the M77001 study group. J Clin Oncol 23: 4265–4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metro G., Foglietta J., Russillo M., Stocchi L., Vidiri A., Giannarelli D., et al. (2011) Clinical outcome of patients with brain metastases from HER2-positive breast cancer treated with lapatinib and capecitabine. Ann Oncol 22: 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster P., Krop I., Miller K., Dhindsa N., Niyijiza C., Nielsen U., et al. (2013) Assessment of safety and activity in an expanded phase 1 study of MM-302, a HER2-targeted liposomal doxorubicin, in patients with advanced HER2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer. Poster presentation, P4–12–29, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R., Yuan L., Zhang B., Kobayashi R., Esteva F. (2005) Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 65: 11118–11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen D., Kumler I., Palshof J., Andersson M. (2013) Efficacy of HER2-targeted therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Breast 22: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom J., Gorlatov S., Zhang W., Yang Y., Huang L., Burke S., et al. (2011) Anti-tumor activity and toxicokinetics analysis of MGAH22, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody with enhanced Fcγ receptor binding properties. Breast Cancer Res 13: R123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegram M., Tan-Chiu E., Miller K., Rugo H., Yardley D., Liv S., et al. (2014) A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study of MGAH22 (Margetuximab) [fc-optimized chimeric anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (mAb)] in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced breast cancer whose tumors express HER2 at the 2+ level by immunohistochemistry and lack evidence of HER2 gene amplification by FISH. J Clin Oncol 32(Suppl. 15): abstract TPS671. [Google Scholar]

- Perez E., Romond E., Suman V., Jeong J., Sledge G., Geyer C., Jr., et al. (2014) Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol 32: 3744–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G., Fields C., Li G., Dowbenko D., Schaefer G., Miller K., et al. (2014) Dual targeting of HER2-positive cancer with trastuzumab emtansine and pertuzumab: critical role for neuregulin blockade in antitumor response to combination therapy. Clin Cancer Res 20: 456–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivot X., Manikhas A., Zurawski B., Chmielowska E., Karaszewska B., Allerton R., et al. (2015) Cerebel (EGF111438): a phase III, randomized, open-label study of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus trastuzumab plus capecitabine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 33: 1564–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran S., Discafani C., Rosfjord E., Baxter M., Floyd M., Golas J., et al. (2004) Antitumor activity of HKI-272, an orally active, irreversible inhibitor of the HER-2 tyrosine kinase. Cancer Res 64: 3958–3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert N., Leyland-Jones B., Asmar L., Belt R., Ilegbodu D., Loesch D., et al. (2006) Randomized phase III study of trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and carboplatin compared with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in women with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 2786–2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugo H. (2004) Bevacizumab in the treatment of breast cancer: rationale and current data. Oncologist 9(Suppl. 1): 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saura C., Garcia-Saenz J., Xu B., Harb W., Moroose R., Pluard T., et al. (2014) Safety and efficacy of neratinib in combination with capecitabine in patients with metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32: 3626–3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer W., Friess T., Burtscher H., Bossenmaier B., Endl J., Hasmann M. (2009) Strongly enhanced antitumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment on HER2-positive human xenograft tumor models. Cancer Res 69: 9330–9336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman A., Berry D., Cirrincione C., Harris L., Muss H., Marcom P., et al. (2008) Randomized phase III trial of weekly compared with every-3-weeks paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer, with trastuzumab for all HER-2 overexpressors and random assignment to trastuzumab or not in HER-2 nonoverexpressors: final results of cancer and leukemia group B protocol 9840. J Clin Oncol 26: 1642–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R., Miller K., Jemal A. (2015) Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 65: 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]