Abstract

A case of a latissimus dorsi myotendinous junction strain in an avid CrossFit athlete is presented. The patient developed acute onset right axillary burning and swelling and subsequent palpable pop with weakness while performing a “muscle up.” Magnetic resonance imaging examination demonstrated a high-grade tear of the right latissimus dorsi myotendinous junction approximately 9 cm proximal to its intact humeral insertion. There were no other injuries to the adjacent shoulder girdle structures. Isolated strain of the latissimus dorsi myotendinous junction is a very rare injury with a scarcity of information available regarding its imaging appearance and preferred treatment. This patient was treated conservatively and was able to resume active CrossFit training within 3 months. At 6 months postinjury, he had only a mild residual functional deficit compared with his preinjury level.

Keywords: latissimus, dorsi, tendon, muscle, tear, magnetic resonance imaging

The latissimus dorsi (LD) is a large fan-shaped muscle spanning the majority of the back, with broad origin, including the inferior thoracic spine and ribs, iliac crest, and the thoracolumbar fascia. Injury of the LD typically occurs in the setting of an acute traumatic event and most commonly involves an avulsion injury of the tendon. LD injuries often occur synchronously with trauma to the adjacent shoulder girdle structures and are rare in isolation. Moreover, isolated tears of the myotendinous junction of the LD are very rare in occurrence, with only a few cases described in the literature.10,15,16 Information regarding the imaging appearance as well as the preferred treatment and outcomes related to this injury are sparse.

We present a case of an isolated high-grade strain of the LD myotendinous junction in an avid CrossFit athlete, treated conservatively.

Case Report

A very active 43-year-old man presented with a 6-week history of posterolateral right chest wall and axillary pain. The patient’s initial injury occurred while performing a “muscle up” exercise (see Video 1, available at http://sph.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data) during a CrossFit routine, at which time he had acute onset of burning pain, stiffness, and swelling in the axilla. The symptoms resolved over a 2-week period of rest, and he returned to his normal activities. One week later, while performing the same “muscle up” exercise, he felt an acute painful pop and “crunch” in his right axilla with immediate onset weakness. The patient’s symptoms only mildly improved with 3 weeks of rest, leading to his presentation. His past medical history was unremarkable, and he denied anabolic steroid use.

Physical examination demonstrated swelling with minimal ecchymosis involving the posterolateral chest wall. There was a noticeable lump at the lateral aspect of the LD muscle belly approximately 10 cm proximal to the humeral insertion, which was painful on palpation. The patient had full range of motion of his shoulder, with active elevation of 160°, external rotation of 60°, and external rotation with abduction of 90°. External rotation and abduction strength were normal. Adduction and internal rotation were asymmetrically decreased on the right (4/5). Teres minor was strong in the horn blower’s position. Modified wing test demonstrated mild weakness in the teres major.

Based on the history and physical examination, a diagnosis of a teres major or LD strain was made. The patient was counseled regarding conservative nonoperative treatment of this injury, especially in the setting of avoidance of such higher level–inciting strengthening exercises. The patient did not want to alter his exercise routine and was concerned with developing a strength deficit. Therefore, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered to evaluate the severity and nature of the tear before considering surgery.

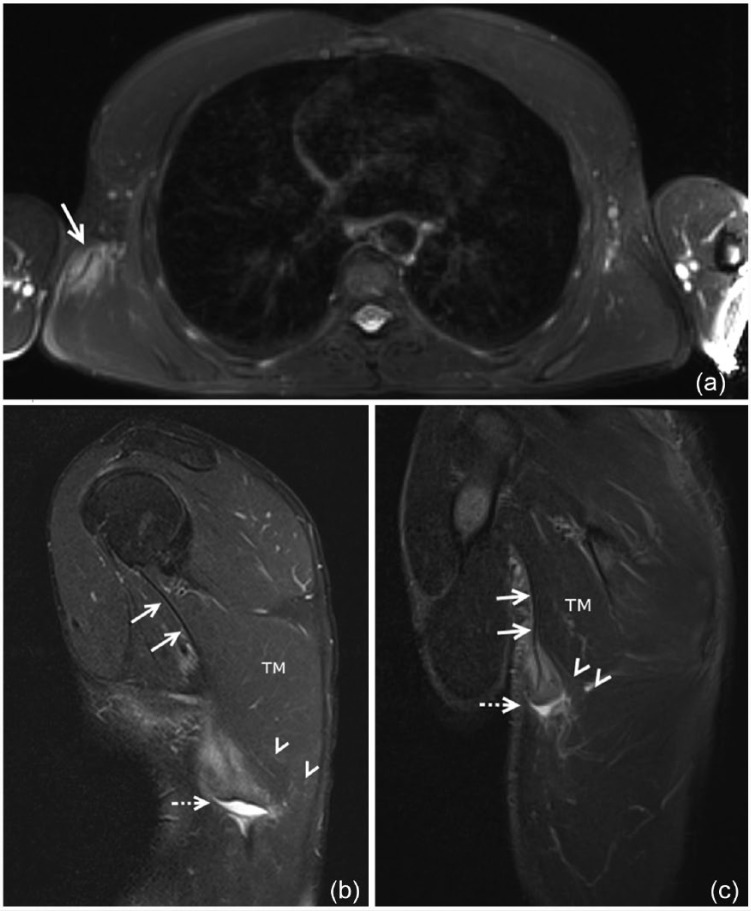

Radiographs were not obtained. An MRI scan demonstrated a high-grade tear of the right LD myotendinous junction approximately 9 cm proximal to its intact humeral insertion (Figure 1). The tear was horizontally oriented, resulting in complete rupture of the myotendinous junction involving the inferior, vertically oriented, and transitional fibers of the LD. The more superior, horizontally oriented fibers remained intact. The torn myotendinous edges were retracted approximately 3 cm, with a small hematoma in the retraction bed.

Figure 1.

(a) Axial fat-saturated T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the upper chest demonstrates asymmetric edema at the myotendinous junction of the right latissimus dorsi (LD) (arrow). (b) Sagittal fat-saturated T2-weighted and (c) oblique coronal short tau inversion recovery magnetic resonance image of the posterolateral right chest wall showing a high-grade strain of the myotendinous junction involving the vertically oriented inferior and midtransitional fibers of the LD with retraction and fluid gap (dotted arrow). The horizontally oriented superior fibers (arrowheads) coursing beneath the teres major (TM) remain intact. The proximal LD tendon remains intact (arrows).

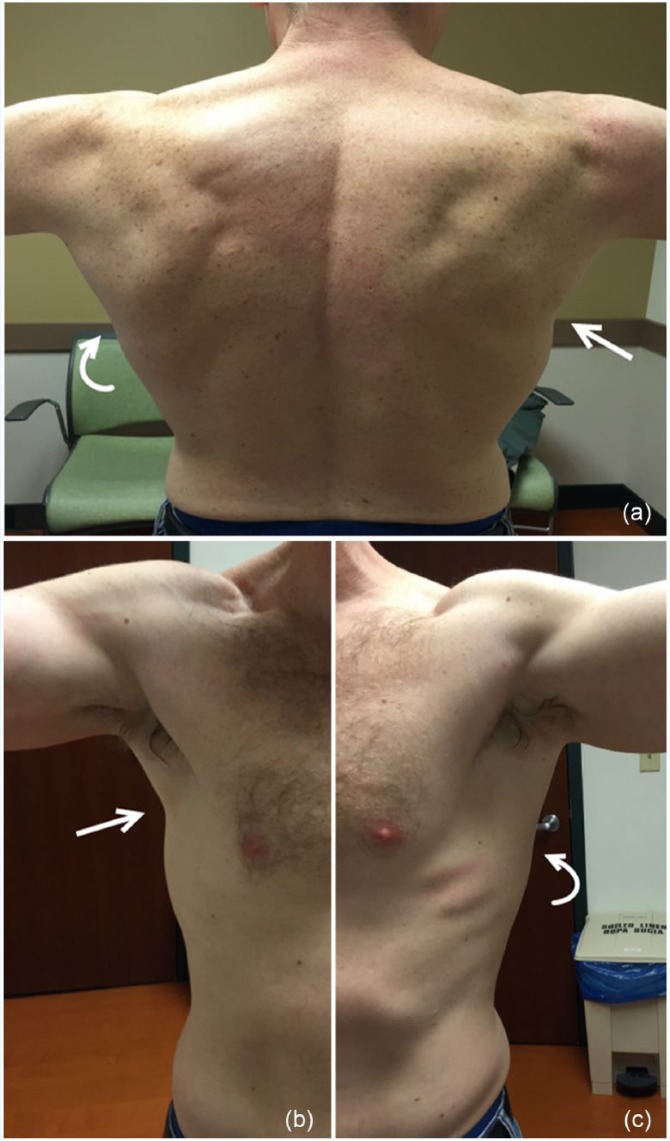

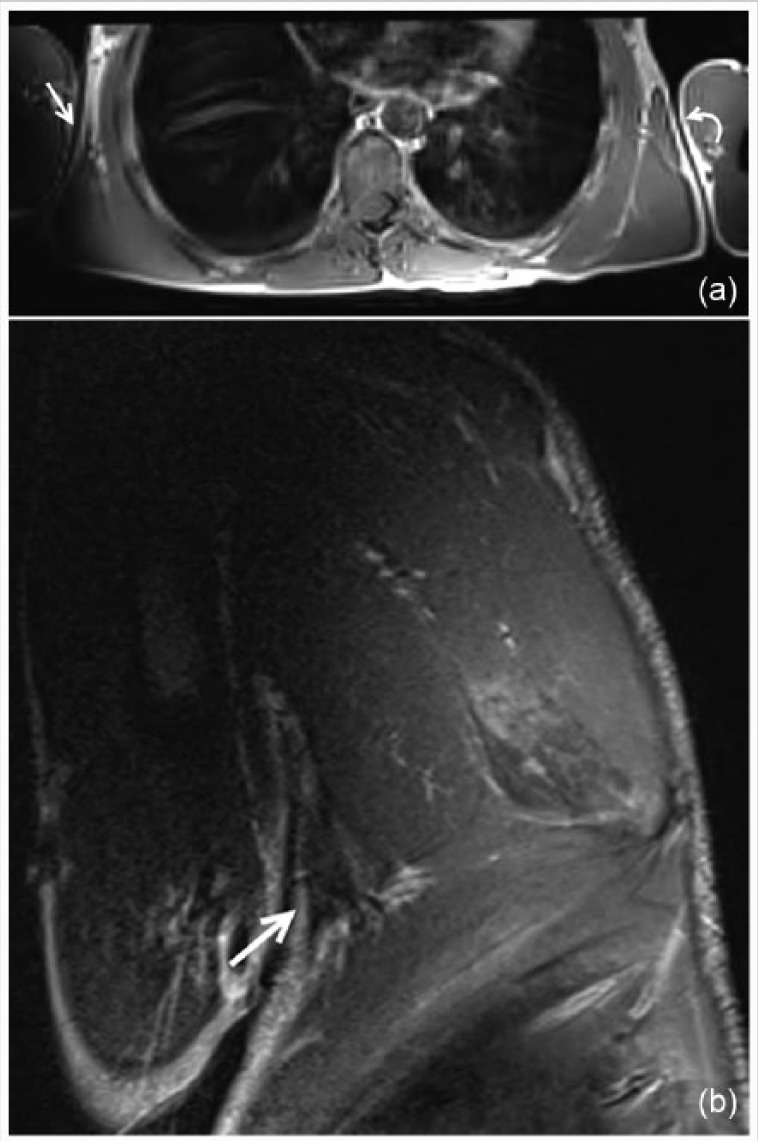

The patient was treated conservatively, with restrictions to adduction, extension, and internal rotation. The patient’s swelling and pain resolved over the next 3 weeks, at which time physical therapy was initiated. On physical examination 6 months postinjury, the patient demonstrated full range of motion of his shoulder, with reconstitution of full strength of arm adduction and internal rotation, to the contralateral comparison. There was some asymmetry in the contour of his latissimus on the right side of his chest wall (Figure 2). The patient reported resuming his full CrossFit exercise routine with the exception of “muscle ups” per his preference. He reported a mild residual physical deficit with strength estimated at approximately 85% of preinjury level. Repeat MRI was performed at the patient’s behest, which demonstrated interval healing of the LD myotendinous strain with scar formation (Figure 3). Mild asymmetric atrophy of the anterior lip of the right LD had developed.

Figure 2.

(a) Posterior, (b) anterior right, and (c) anterior left pictures of the patient demonstrating mild asymmetric atrophy of the right latissimus dorsi (LD) (arrows) in comparison with the normal contralateral left LD (curved arrows).

Figure 3.

(a) Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the upper chest demonstrates asymmetric atrophy of the anterior lip of the right latissimus dorsi (arrow) in comparison to the left (curved arrow). (b) Oblique coronal short tau inversion recovery magnetic resonance image of the posterolateral right chest wall showing nodular scar formation at the prior myotendinous junction strain (arrow).

Discussion

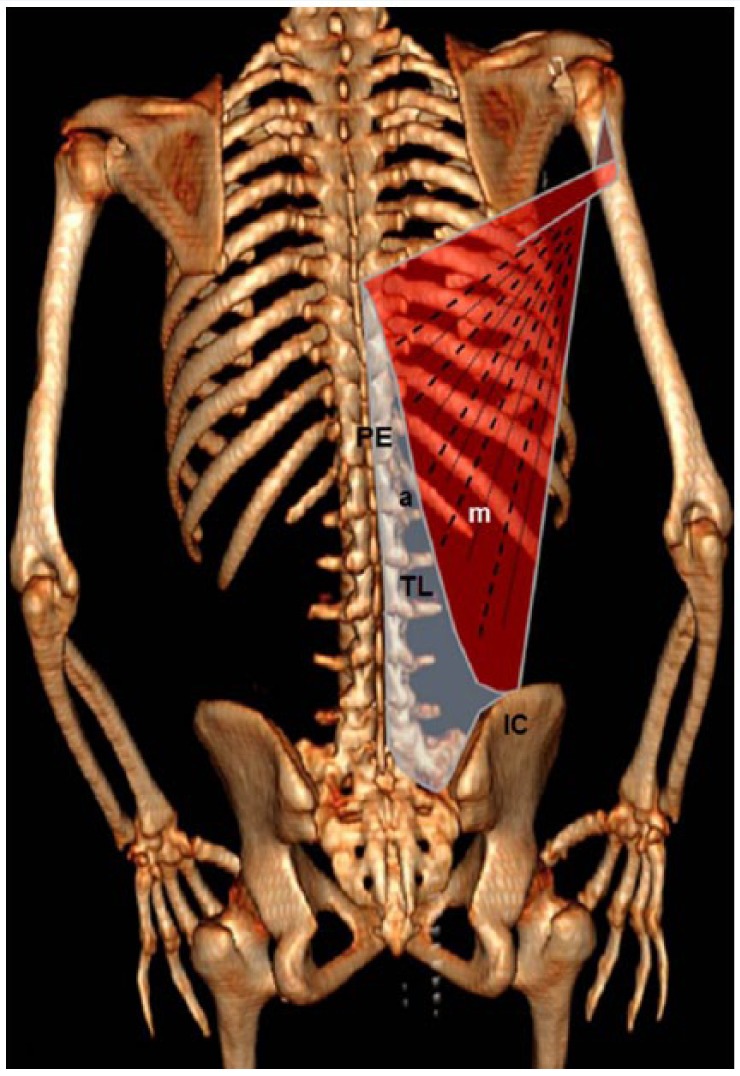

Aptly named, the LD is the broadest muscle of the back with transitioning muscle fibers originating from the inferior 6 thoracic vertebra posterior elements, the inferior 3 or 4 ribs, the thoracolumbar fascia, and the iliac crest (Figure 4). The fibers coalesce to form the LD tendon, which crosses the inferior angle of the scapula, rotates upon itself, and inserts on the intertubercle groove of the humerus, lateral to the teres major and medial to the pectoralis major (“the lady between the majors”).

Figure 4.

Diagram of the latissimus dorsi (LD) with anatomical distribution overlying computed tomography 3-dimensional reconstruction of the skeleton showing the broad origin of the LD including the posterior elements (PE) of the lumbar and inferior 6 thoracic vertebra, the thoracolumbar fascia (TL), and the iliac crest (IC). The transition in orientation of the aponeurosis (a) and muscle fibers (m) from the vertically oriented inferior fibers to the more horizontally oriented superior fibers is demonstrated.

Injury of the LD usually occurs in the acute setting of forceful abduction and external rotation during resisted contraction, such as attempting to catch oneself during a fall on an outstretched arm or pulling the body upward and forward while the arms are overhead with fixed hand positioning. A “muscle up” is an advanced CrossFit training maneuver where athletes essentially perform a pull-up with transition to performing a dip in 1 fluid maneuver. Accomplishing this exercise requires great strength and technique, including a tremendous exertional force at the transition point of the maneuver. Patients with LD injuries often report an acute onset tearing, burning, or popping sensation in the axilla with subsequent pain and weakness.10 Presentation may include ecchymosis of the axilla and palpable mass that can simulate a sarcoma.1,7 Recent advances have shown both MRI and ultrasonography as imaging modality options that provide useful information, allowing characterization of these injuries into 4 basic categories: (1) isolated tendon injury/avulsion1,5,7-9,11,13,14,17,19; (2) combination injuries with LD tendon injury associated with trauma to the adjacent pectoralis major, teres major, or rotator cuff3,12,14,17,18; (3) isolated myotendinous strain10,15,16; and (4) intramuscular strain.2,4

Treatment of LD injuries remains controversial, with the standard of care yet to be established. Multiple case reports of LD injuries in high-level2-4,7-9,13-17 and recreational athletes1,5,10-12,18,19 have been managed both surgically and nonoperatively without defined consistency. Authors of the largest series currently available suggest that conservative management is an acceptable approach to LD injuries, even in the high-level athlete, without evidence of deficit on follow-up.14,16,17 However, other authors have argued for surgical treatment of high-level athletes to preserve muscle strength and function, as well as reestablishing anatomy, which may be difficult in the setting of failed conservative treatment.6,7,11,15 This has led to a current trend of thought that conservative management of LD injuries in the recreational athlete is likely satisfactory because the remaining shoulder girdle can compensate for the acquired deficiencies. However, for the elite athlete, surgical management may be the preferred approach to offer the greatest chance of successful return to play at the preinjury level.6

In the authors’ experience, imaging often provides valuable information when determining between conservative versus surgical treatment of LD injuries. MRI is the imaging modality of choice with superior sensitivity in soft tissue evaluation. An MRI scan provides important presurgical information of the nature of the injury, specifically, distinguishing between tendinous and myotendinous etiologies, as well as evaluating the extent of tendon retraction or tendinopathy. The majority of reported myotendinous and muscular injuries of the LD have been treated conservatively,2-4,10,16 with only 1 patient reporting development of a mild functional deficit.3

Conclusion

Isolated myotendinous injuries of the LD are a rare occurrence. With the continued evolution and popularization of new and extreme training methods, these injuries may become more commonplace. The standard of care of treatment of myotendinous LD injuries remains to be determined; however, both high-level and recreational athletes have had good outcomes with conservative measures. We present a case of a myotendinous LD injury in a recreational athlete, managed conservatively. The patient returned to complete preinjury level of activity within 6 months after the inciting event, with mild residual functional deficit.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Anderson SE, Hertel R, Johnston JO, Stauffer E, Leinweber E, Steinbach LS. Latissimus dorsi tendinosis and tear: imaging features of a pseudotumor of the upper limb in five patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1145-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balius R, Pedret C, Dobado MC, Vives J. Latissimus dorsi costal tear in an elite handball player. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:859-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butterwick DJ, Mohtadi NG, Meeuwisse WH, Frizzell JB. Rupture of latissimus dorsi in an athlete. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:189-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Çelebi MM, Ergen E, Üstüner E. Acute traumatic tear of latissimus dorsi muscle in an elite track athlete. Clin Pract. 2013;3:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cox EM, McKay SD, Wolf BR. Subacute repair of latissimus dorsi tendon avulsion in the recreational athlete: two-year outcomes of 2 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:e16-e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ellman MB, Yanke A, Juhan T, et al. Open repair of retracted latissimus dorsi tendon avulsion. Am J Orthop. 2013;42:280-285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hapa O, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF, Braman JP. Out of the ring and into a sling: acute latissimus dorsi avulsion in a professional wrestler: a case report and review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:1146-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henry JC., Scerpella TA. Acute traumatic tear of the latissimus dorsi tendon from its insertion. A case report. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:577-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hiemstra LA, Butterwick D, Cooke M, Walker RE. Surgical management of latissimus dorsi rupture in a steer wrestler. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:316-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Le HB, Lee S, Lane M, Munk PL, Blachut PA, Malfair D. Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of partial latissimus dorsi muscle tendon tear. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:1107-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levine JW, Savoie FH., 3rd Traumatic rupture of the latissimus dorsi. Orthopedics. 2008;31:799-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lim JK, Tilford ME, Hamersly SF, Sallay PI. Surgical repair of an acute latissimus dorsi tendon avulsion using suture anchors through a single incision. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1351-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Livesey JP, Brownson P, Wallace WA. Traumatic latissimus dorsi tendon rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:642-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagda SH, Cohen SB, Noonan TJ, Raasch WG, Ciccotti MG, Yocum LA. Management and outcomes of latissimus dorsi and teres major injuries in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2181-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park JY, Lhee SH, Keum JS. Rupture of latissimus dorsi muscle in a tennis player. Orthopedics. 2008;31:1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pedret C, Balius R, Idoate F. Sonography and MRI of latissimus dorsi strain injury in four elite athletes. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schickendantz MS, Kaar SG, Meister K, Lund P, Beverley L. Latissimus dorsi and teres major tears in professional baseball pitchers: a case series. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2016-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spinner RJ, Speer KP, Mallon WJ. Avulsion injury to the conjoined tendons of the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:847-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Turner J, Stewart M. Latissimus dorsi tendon avulsion: 2 case reports. Inj Extra. 2005;36:386-388. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.