Abstract

The progression of atherosclerosis is favored by increasing amounts of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the artery wall. We previously reported the reactivity of chP3R99 monoclonal antibody (mAb) with sulfated glycosaminoglycans and its association with the anti-atherogenic properties displayed. Now, we evaluated the accumulation of this mAb in atherosclerotic lesions and its potential use as a probe for specific in vivo detection of the disease. Atherosclerosis was induced in NZW rabbits (n = 14) by the administration of Lipofundin 20% using PBS-receiving animals as control (n = 8). Accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic lesions was assessed either by immunofluorescence detection of human IgG in fresh-frozen sections of aorta, or by immunoscintigraphy followed by biodistribution of the radiotracer upon administration of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb. Immunofluorescence studies revealed the presence of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic lesions 24 h after intravenous administration, whereas planar images showed an evident accumulation of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic rabbit carotids. Accordingly, 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb uptake by lesioned aortic arch and thoracic segment was increased 5.6-fold over controls and it was 3.9-folds higher in carotids, in agreement with immunoscintigrams. Moreover, the deposition of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in the artery wall was associated both with the presence and size of the lesions in the different portions of evaluated arteries and was greater than in non-targeted organs. In conclusion, chP3R99 mAb preferentially accumulates in arterial atherosclerotic lesions supporting the potential use of this anti-glycosaminoglycans antibody for diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: monoclonal antibodies, glycosaminoglycans, atherosclerosis, technetium-99m, imaging

Abbreviations

- % ID/g

percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue

- At-R

Atherosclerotic rabbits

- CS

chondroitin sulfate

- CSPG

chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans

- DS

dermatan sulfate

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunoadsorbent assay

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- Non At-R

Non atherosclerotic rabbit

- NZW rabbits

New Zealand White rabbits

- PG

proteoglycans

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the underlying pathology of most cardiovascular events and the main cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 This disease is characterized by a non-resolved inflammatory response triggered by the retention of apoB-containing lipoproteins in the artery wall.2,3 Upon entrapment in the intima layer, proatherogenic lipoproteins undergo oxidative and enzymatic modifications thereby increasing their immunogenicity.4 These modifications also trigger the uptake of lipoprotein by macrophages and vascular smooth muscle cells, which leads to foam cells formation.4,5

Subendothelial retention of low density lipoprotein (LDL) is mediated by electrostatic interactions between positively charged residues on apolipoprotein B-100 (apoB-100) and negatively charged glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) chains on proteoglycans (PGs).6,7 A prominent feature of atherosclerosis progression is the accumulation of chondroitin sulfate (CS) and dermatan sulfate (DS) PGs, accompanied by hyperelongation of GAGs side chains.8,9 CSPG-LDL complexes have been detected in injured rabbit intima,10 and they have also been isolated from human atherosclerotic lesions.11

In a previous work, we characterized the antiatherogenic properties of the chimeric mouse/human monoclonal antibody (mAb) chP3R99, which binds sulfated GAGs, inhibits LDL binding to CS, and abrogates LDL oxidation in vitro. Moreover, rabbits immunized with chP3R99 mAb showed reduced aortic arch lesions and no macrophage infiltration following short-term treatment with Lipofundin 20% (referred to as Lipofundin).12 Similar results were observed in ApoE−/− mice fed with a high-fat high-cholesterol diet in which the administration of chP3R99 mAb reduced the total lesion area in more than 40%.13

In this paper, we demonstrated that chP3R99 mAb preferentially accumulates in rabbit atherosclerotic lesions, supporting the use of anti-GAGs antibodies for the detection and treatment of atherosclerosis.

Results

chP3R99 mAb reactivity to rabbit atherosclerotic lesions

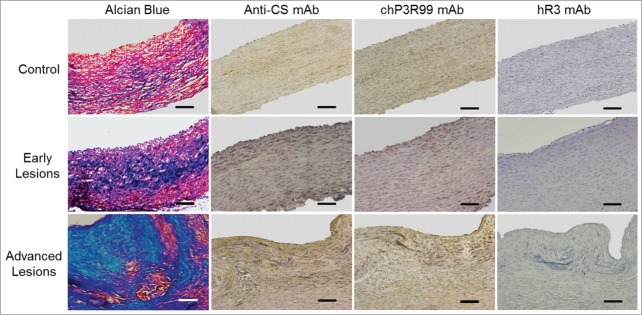

To evaluate the content of GAG in the artery wall, aortic sections from normal and Lipofundin-treated rabbits were stained with Alcian Blue. As depicted in Figure 1, the amounts of GAGs increased in the aortic arch depending on the presence and size of the lesions. Particularly, immunohistochemistry revealed a high content of CS in the aortic lesions of Lipofundin-receiving rabbits, which results in a strong reactivity of chP3R99 mAb in these areas. A lower reactivity was observed in aortic sections from the control rabbits and in Type I AHA lesions, whereas the isotype-matched control (hR3 mAb) did not react with any of the aortic sections.

Figure 1.

chP3R99 mAb reactivity to Lipofundin-induced atherosclerotic plaque from rabbit aorta. GAGs were detected in the artery wall of normal and Lipofundin-treated rabbits by Alcian Blue staining and immunohistochemistry with CS-56 mAb (1 μg/mL). Samples from normal aorta and sections corresponding to areas with early and advanced lesions were incubated with chP3R99 mAb or the isotype-matched control hR3 (2 μg/mL). Original magnification X20. Scale bars = 100 μm.

chP3R99 mAb accumulation in Lipofundin-induced lesions

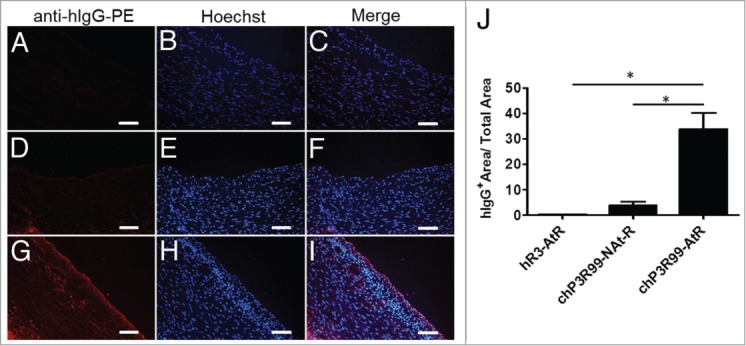

The accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic lesions in vivo was addressed by immunofluorescence upon intravenous injection of 1 mg of the mAb in rabbits receiving or not Lipofundin (Fig. 2). Unlike hR3 mAb (Fig. 2A–C), chP3R99 was detected in lesioned arterial tissue, adventitia and the surface of smooth muscle cells of atherosclerotic rabbits (Fig. 2G–I). In contrast, both the presence of this anti-GAGs mAb and the intensity of the fluorescence were lower in the aorta of healthy animals, and located predominantly in the adventitia (Fig. 2D–F). In fact, as depicted in Figure 2J, the accumulation of chP3R99 was significantly higher (8.7-fold) in atherosclerotic rabbits than in controls; and also higher (135-fold) than the accumulation of the isotype-matched mAb in atherosclerotic rabbits (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence detection of in vivo chP3R99 accumulation in Lipofundin-induced atherosclerotic lesions. Representative images from atherosclerotic rabbits injected with 1 mg of the isotype matched control (A–C) or chP3R99 mAb (G–I). Frozen sections from healthy rabbits who received the same mass of chP3R99 are shown (D–F). Human antibodies were detected through the incubation with a goat phycoerythrine (PE)-conjugated anti-human IgG followed by counterstaining with Hoechst. Original magnification X20. Scale bars = 100 μm. (J) Represents the percentages of human IgG stained areas respect to total area. At-R = atherosclerotic rabbits; NAt-R = non atherosclerotic rabbits. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

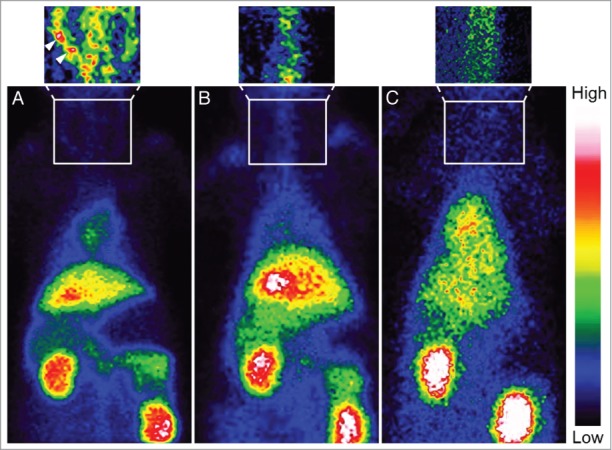

These results were confirmed by immunoscintigraphy by intravenous administration of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic and control rabbits (Fig. 3). Ten minutes after the injection of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb or the isotype-matched control 99mTc-chT3 mAb, blood-pool images were similar in all animals (data not shown). The overall uptake was predominantly localized in liver, kidneys and heart alongside all time intervals. Planar images acquisition revealed the accumulation of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in the carotid of atherosclerotic rabbits 6 h after radiotracer administration (Fig. 3A), but not in control animals (Fig. 3B). The visualization of atherosclerotic lesions upon 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb injection was specific, since no evident accumulation of 99mTc-chT3 mAb was observed in Lipofundin-receiving rabbits (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Immunoscintigrams of rabbits injected with 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb or 99mTc-chT3 mAb. Planar images acquired at 6 h after radiotracers injection, showed a selective accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in carotids (arrowhead) from rabbits with Lipofundin-induced atherosclerotic lesions (A) but not in healthy rabbits (B). No accumulation of the isotype-matched control mAb was observed in atherosclerotic lesions (C).

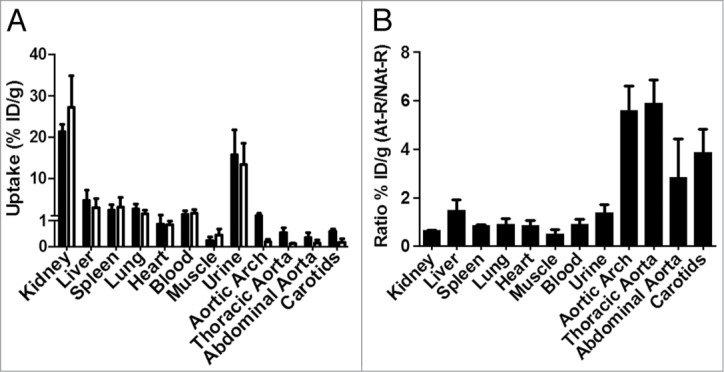

99mTc-chP3R99 mAb arterial uptake

The distribution of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in rabbits is summarized in Figure 4. The percentage of injected dose of the radiotracer per gram of tissue (% ID/g) in samples of Lipofundin-treated rabbits was greater in kidney (21.3 ± 1.8% ID/g) and urine (15.7 ± 6.0% ID/g). As depicted in Figure 4A and 4B, we found similar mAb uptake by non-targeted organs without marked differentiation between lesioned and non-lesioned rabbits, (P > 0.05). In contrast, 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb accumulation into atherosclerotic lesions was greater than the one observed in the artery wall of control rabbits, both for aortic arch (1.019 ± 0.294% ID/g vs. 0.187 ± 0.097% ID/g) and thoracic segment (0.547 ± 0.180% ID/g vs. 0.097 ± 0.035% ID/g), (P < 0.05). In these segments, the accumulation of radiolabeled mAb was more than 5-fold higher in Lipofundin-receiving rabbits than in controls (Fig. 4B). According to immunoscintigraphy images, we found that 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb uptake by carotids with lesions was 3.9-fold higher than that in controls (0.597 ± 0.079% ID/g vs. 0.157 ± 0.140% ID/g), (P < 0.05). Although the % ID/g in abdominal portion of aorta from Lipofundin-receiving animals was 2.8-fold higher than in non-atherosclerotic rabbits, no significant differences were observed between these groups (0.356 ± 0.174 ID/g vs. 0.139 ± 0.121% ID/g), (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Biodistribution of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb in rabbits determined as % ID/g 6 h after radiotracer administration. (A) Radiotracer uptake by organs. Black and white bars represent the % ID/g in atherosclerotic and healthy rabbits, respectively. (B) Ratio of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb uptake by samples from rabbits with Lipofundin-induced atherosclerosis to non-atherosclerotic rabbits. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. At-R = atherosclerotic rabbits; NAt-R = non atherosclerotic rabbits.

Also, chP3R99 mAb accumulation in aortic arch from rabbits with atheromatous plaques was 1.7-fold and 2.5-fold higher than in thoracic and abdominal segments, respectively. In addition, the % ID/g ratio of arterial segments-to-muscle and arterial segments-to-blood were significantly greater in Lipofundin-receiving rabbits than in controls (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biodistribution of chP3R99 mAb in arterial segments

| Control rabbits (n = 3) |

Atherosclerotic rabbits (n = 4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial Segment | A/M | A/B | A/M | A/B |

| Aortic Arch | 0.47 ± 0.26 | 0.14 ± 0.12 | 7.09 ± 1.12* | 0.93 ± 0.36* |

| Thoracic | 0.80 ± 0.30 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 5.12 ± 1.59* | 0.50 ± 0.32* |

| Abdominal | 0.55 ± 0.09 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 2.34 ± 0.08* | 0.55 ± 0.38 |

| Carotids | 0.77 ± 0.19 | 0.27 ± 0.18 | 2.67 ± 0.35* | 0.75 ± 0.19* |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. A/M: arteria-to-muscle ratio; A/B: arteria-to-blood ratio; *P < 0.05 vs. control group.

Histopathological study

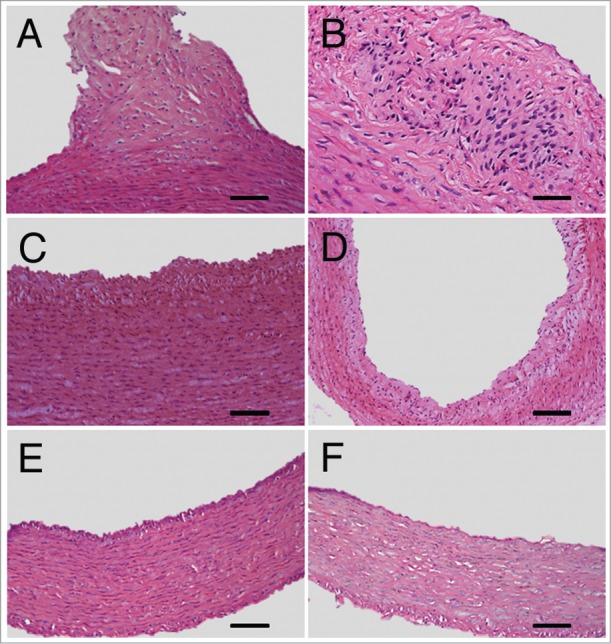

99mTc-chP3R99 mAb accumulation in different segments of the aorta and carotids was associated to lesions size of Lipofundin-receiving rabbits (Fig. 5). Histopathological studies revealed the presence of atherosclerotic lesions in aortic arch (Fig. 5A and 5B) and thoracic segment (Fig. 5C) of aorta and carotids (Fig. 5D), characterized by intimal thickening, leukocyte infiltration and distortion of smooth muscle cells arrangement. In contrast, only a slight thickening of the intima was observed in the abdominal segment (Fig. 5E). The aortas from PBS-receiving rabbits showed no alteration in the vascular architecture (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

Representative atherosclerotic lesions developed in aortic segments and carotids of Lipofundin-receiving rabbits. Hematoxylin-Eosin shows intimal thickening, leukocyte infiltration and distortion in the vascular tissue architecture in aortic arch (A, B), thoracic segment (C) and carotids (D) of Lipofundin-treated rabbits. Minor lesions were observed in the abdominal segment of aorta (E) whereas no alteration in the artery wall of normal rabbits was detected (F). Original magnification X20 except for B (X40). Scale bars = 50 μm except for (D) where bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

The use of therapeutic agents targeting the arterial wall, especially those aimed at preventing the retention of proatherogenic lipoproteins in the subendothelial matrix, is a promising strategy which has been poorly addressed.14 Previously, we reported that chP3R99 mAb prevents atherosclerosis in rabbits; presumably through the induction of autologous anti-CS antibodies generated upon immunization. However, a direct proof of the reactivity of chP3R99 mAb or those antibodies with the rabbit artery wall was not demonstrated.12 Now, we showed that chP3R99 mAb specifically recognizes atherosclerotic lesions, in a close association with their size and the presence of CS GAGs. The development of atherosclerosis is characterized by a shifting of contractile vascular smooth muscle cells toward secretory phenotype, thereby affecting the composition and atherogenicity of PGs produced.15 For instance, it have been described a prominent accumulation of CSPGs, throughout the artery wall16 with elongated GAGs chains and higher sulfation degree at atherosclerosis-prone sites.17,18

Hence, these results might suggest the feasibility of using this anti-GAG mAb in advanced stages of the disease in order to reduce lesions size or to halt their growth. In rabbits, the acute administration of Lipofundin induces American Heart Association type III-IV atherosclerotic lesions characterized by accumulation of abundant GAGs and collagen fibers in the subendothelial space, along with macrophages infiltration.12

According to the in vitro results, immunoscintigraphy and immunofluorescence analysis revealed a preferential accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic plaques in rabbits. In contrast to the isotype-matched control, chP3R99 mAb showed sustained accumulation within carotids from Lipofundin-treated rabbits, but not in the arteries of control animals, resulting in a specific uptake by atherosclerotic lesions. These results agreed with a higher detection of the chimeric antibody by immunofluorescence in frozen aortic sections from rabbits with lesions. In the same line, Brito and coworkers reported that chP3R99-fluorescein isothiocyanate injected intravenously colocalizes with activated endothelial areas of aorta in ApoE−/− mice fed a high-fat high-cholesterol diet.13

Due to the small size of atherosclerotic plaques and the close proximity of aorta to heart and liver we could not visualize this artery by immunoscintigraphy. Notwithstanding, as revealed in biodistribution studies, the uptake of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb by aortic arch and thoracic segment from atherosclerotic rabbits was almost 6-folds higher than by the arterial wall of healthy animals. In addition, radiotracer uptake was not evenly distributed throughout the descending aorta and was related with the size of lesions detected in these areas. Indeed, 99mTc-chP3R99 accumulation in the aortic cross was 2.5-fold greater than in abdominal segment in atherosclerotic rabbits. Although it has been described that LDL retention in the artery wall is similar among all aortic sites of normal rabbits, it is increased at atherosclerosis-susceptible areas as soon as 4 d after feeding with hypercholesterolemic diet.19

Here, we also demonstrated that Lipofundin, in addition to develop atherosclerosis in aorta, also induces lesions in carotids as reflected by the thickening of the intima layer, extracellular matrix production and distortion in the arrangement of smooth muscle cells. Thus, we found almost a 4-folds increase in 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb uptake into this artery, supporting the accumulation of the mAb observed by immunoscintigraphy.

Until now, most of the efforts in the development of radiotracers to detect atherosclerotic lesions have been focused on the identification of important pathways associated with plaque instability, such as macrophage recruitment, matrix breakdown enzyme, macrophage metabolism, thrombosis and apoptosis.20,21 However, since CS/DS PGs are produced in large quantities during all the stages of human atherosclerosis development they could be a good target to detect atherosclerotic lesions, even in early phases of the disease.22,23 This could be useful in atherosclerosis diagnosing as a criterion to prescribe artery wall-based therapies.17

Because we used as radiotracer a full-sized mAb tagged with 99Tc, there was a slow blood clearance of the probe, resulting in a suboptimal target-to-background ratio. Hence, the 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb uptake detected by immunoscintigraphy in the lesioned carotids could be attributable to both specific accumulation and blood pool radiactivity. However, it was possible to observe a focal accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in some regions of carotids from Lipofundin-receiving rabbits along with higher A/B and A/M ratios in these animals. Conversely, we could not detect neither chP3R99 mAb in carotids from healthy animals nor accumulation of the isotype-matched control mAb in atherosclerotic plaques.

Future studies using fragments of chP3R99 mAb (Fab, scFv) or engineered variants (diabodies, triabodies, minibodies, and single-domain antibodies) are required in order to optimize the targeting of atherosclerotic lesions with a fast clearance from circulation.24,25 A recent approach for cardiovascular applications is the use of nanobodies as radiotracers, displaying high stability, fast blood clearance, and the possibility of labeling with different probes thereby allowing atherosclerotic lesions imaging.26

In summary, our results show that chP3R99 mAb preferentially accumulates in atherosclerotic lesions, even at early phases of the disease, supporting the potential use of this anti-GAGs antibody for diagnosing and treatment of atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

chP3R99, chT3 (anti-human CD3)27 and hR3 (anti-Epidermal Growth Factor receptor)28 mAbs were purified by protein-A affinity chromatography (Pharmacia) from transfectoma culture supernatants and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Animals

New Zealand White (NZW) male rabbits (3.0–3.5 kg, 12 wk old) were obtained from the National Center for the Production of Laboratory Animals (CENPALAB, Mayabeque, Cuba). Animals were housed under standard conditions (25°C, 60 ± 10% humidity), 12 h day/night cycles with water and food ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethic Committee.

Radiolabeling of mAbs

Labeling of mAbs with 99mTc was performed according to a method previously reported.29 Briefly, mAbs were reduced at a 2-mercaptoethanol-to-mAb molar ratio of 850:1 at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. After purification by a PD-10 column chromatography (Sephadex G-25), the reactivity of the reduced mAbs to CS (Sigma) was determined by ELISA, as previously described.12 Then, 84 mg of sodium pyrophosphate and 2 mg of stannous chloride were diluted in 5.0 mL of sodium chloride 0.9% and 100 μL of this mixture were added to 1 mg of the reduced mAbs. The samples were incubated for 15 min at RT followed by a 30 min incubation with 1295 MBq (35 mCi) 99mTc pertechnetate eluted from a 99mMo–99mTc generator (CENTIS, Mayabeque, Cuba). Quality control was determined by thin-layer chromatography using both acetone and sodium chloride 0.9% as mobile phase yielding >90% of radiochemical purity.

Cysteine and rabbit sera challenge

Transchelation experiments were performed by challenging 31 μg of 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb with 630 nmol of cysteine at a final molar ratio cysteine to mAb 3000:1, and rabbit sera (volume ratio 20:1) at RT for 24 h. In these extreme conditions we found 40–50% of displacement of the radioactivity.

Accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic lesions

Atherosclerosis was induced in 18 NZW rabbits by daily administration of Lipofundin 20% (Braun Melsungen) (2 mL/kg, 8 d) through marginal ear vein, as previously described.12,30 Eight rabbits that received only PBS were used as control. To evaluate the preferential accumulation of chP3R99 mAb in atherosclerotic lesions, six Lipofundin-treated rabbits and four healthy controls intravenously received 1mg of this antibody into the marginal ear vein the day after the last dose of Lipofundin and were sacrificed 24 h later. Specificity was assessed by administrating the same mass of hR3 mAb in four atherosclerotic rabbits. In other set of experiments, 99mTc-chP3R99 mAb (0.3 mg, 370 MBq) was injected into the marginal ear vein both in Lipofundin-treated (n = 4) and PBS-receiving rabbits (n = 3). As a control of specificity, two atherosclerotic rabbits received the same dose of 99mTc-chT3 mAb. After 12 h of fasting, rabbits were anesthetized with 35 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride and 5 mg/kg of xylazine HCl, IM. Radioimmunoscintigraphy was performed 10 min after radiotracers injection and repeated 6 h later. Planar images were obtained in the anterior views with a gamma camera (MEDISO) equipped with a low-energy, parallel-hole, high-resolution collimator and stored on a 128 × 128 pixel matrix by means of a digital computer. Images were recorded until 200K counts at the energy peak of 140 keV with a 20% window.

Rabbits were sacrificed by intracoronary injection of KCl under anesthesia and the following organs and tissues were removed, weighed, and counted in a well scintillation γ-counter (CAPINTEC, Inc. CRC-25W): aorta (aortic arch, thoracic and abdominal segments), carotids, heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney and muscle. The radioactivity of blood and urine was counted as well. Radioactivity uptake was expressed as percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g). Specific antibody accumulation in organs was considered when the ratio of % ID/g of atherosclerotic-to-control rabbits was >2.5.

Histological study

Histopathological findings in the different segments of aorta and carotids as well as immunohistochemical studies were performed in formalin-fixed (24 h, pH 7.4) paraffin-embedded tissue samples. The specimens were cut into 5-μm slices, deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin or Alcian Blue for light microscopic examination. The reactivity to the artery wall was evaluated in aortic sections from two rabbits in which the atherosclerotic lesions were induced or unmanipulated ones. After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity (Dako), sections were incubated with chP3R99 mAb or the isotype-matched control hR3 (2 μg/mL) for 1 h at RT, followed by an anti-human IgG serum conjugated to peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab). Anti-CS mAb (clone CS-56, Sigma) was used as positive control (1 μg/mL) and it was identified by the incubation with the EnVision™ Detection Systems (Dako). Finally, sections were incubated with diaminobenzidine substrate solution and counterstained with hematoxylin.

The presence of chP3R99 mAb in the artery wall was detected by immunofluorescence in fresh frozen samples, by incubating tissue sections with a goat phycoerythrine (PE)-conjugated anti-human IgG (BD Bioscience), followed by counterstaining with Hoechst.

Images were digitally captured with a DP20 camera coupled to a fluorescence microscope Olympus BX51. Fluorescence images were quantified by using the software ImageJ 1.47.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. To compare the accumulation of the chimeric antibodies in the artery wall of rabbits in immunofluorescence experiments a one-way ANOVA was performed followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. The % ID/g in organs and ratios between atherosclerotic rabbits and controls were compared by use of the Student t test. A P < 0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Ana María Vázquez, Yosdel Soto and Victor Brito are inventors of a patent related with antibodies that recognize sulfatides and sulfated PGs; however, they have assigned their rights to the assignee Center of Molecular Immunology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center of Molecular Immunology (Havana, Cuba).

References

- 1.Negi S, Anand A. Atherosclerotic coronary heart disease-epidemiology, classification and management. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 2010; 10:257-61; PMID:20932265; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/187152910793743832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: challenges and opportunities. Science 2013; 339:166-72; PMID:23307734; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1230720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science 2013; 339:161-6; PMID:23307733; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1230719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6:508-19; PMID:16778830; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabas I, Williams KJ, Borén J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation 2007; 116:1832-44; PMID:17938300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurt-Camejo E, Olsson U, Wiklund O, Bondjers G, Camejo G. Cellular consequences of the association of apoB lipoproteins with proteoglycans. Potential contribution to atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997; 17:1011-7; PMID:9194748; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.17.6.1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalil MF, Wagner WD, Goldberg IJ. Molecular interactions leading to lipoprotein retention and the initiation of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24:2211-8; PMID:15472124; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147163.54024.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little PJ, Osman N, O’Brien KD. Hyperelongated biglycan: the surreptitious initiator of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2008; 19:448-54; PMID:18769225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32830dd7c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballinger ML, Osman N, Hashimura K, de Haan JB, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Allen T, Tannock LR, Rutledge JC, Little PJ. Imatinib inhibits vascular smooth muscle proteoglycan synthesis and reduces LDL binding in vitro and aortic lipid deposition in vivo. J Cell Mol Med 2010; 14(6B):1408-18; PMID:19754668; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00902.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasan SR, Vijayagopal P, Dalferes ERJ, Jr., Abbate B, Radhakrishnamurthy B, Berenson GS. Dynamics of lipoprotein-glycosaminoglycan interactions in the atherosclerotic rabbit aorta in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta 1984; 793:157-68; PMID:6712964; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90317-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camejo G, Hurt E, Romano M. Properties of lipoprotein complexes isolated by affinity chromatography from human aorta. Biomed Biochim Acta 1985; 44:389-401; PMID:4004839 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soto Y, Acosta E, Delgado L, Pérez A, Falcón V, Bécquer MA, Fraga Á, Brito V, Álvarez I, Griñán T, et al. Antiatherosclerotic effect of an antibody that binds to extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32:595-604; PMID:22267481; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.238659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brito V, Mellal K, Giroux S, Pérez A, Soto Y, deBlois D, Ong H, Marleau S, Vázquez AM. Induction of anti-anti-idiotype antibodies against sulfated glycosaminoglycans reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32:2847-54; PMID:23087361; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabas I. Making things stick in the fight against atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2013; 112:1094-6; PMID:23580771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manderson JA, Mosse PRL, Safstrom JA, Young SB, Campbell GR. Balloon catheter injury to rabbit carotid artery. I. Changes in smooth muscle phenotype. Arteriosclerosis 1989; 9:289-98; PMID:2719591; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.9.3.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakashima Y, Fujii H, Sumiyoshi S, Wight TN, Sueishi K. Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27:1159-65; PMID:17303781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little PJ, Ballinger ML, Osman N. Vascular wall proteoglycan synthesis and structure as a target for the prevention of atherosclerosis. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2007; 3:117-24; PMID:17583182 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoso LEM, Mourão PAS. Glycosaminoglycan fractions from human arteries presenting diverse susceptibilities to atherosclerosis have different binding affinities to plasma LDL. Arterioscler Thromb 1994; 14:115-24; PMID:8274466; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.14.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwenke DC, Carew TE. Initiation of atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits. II. Selective retention of LDL vs. selective increases in LDL permeability in susceptible sites of arteries. Arteriosclerosis 1989; 9:908-18; PMID:2590068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.9.6.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies JR, Rudd JH, Weissberg PL, Narula J. Radionuclide imaging for the detection of inflammation in vulnerable plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47(Suppl):C57-68; PMID:16631511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaudemans AWJM, Slart RHJA, Bozzao A, Bonanno E, Arca M, Dierckx RAJO, Signore A. Molecular imaging in atherosclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010; 37:2381-97; PMID:20306036; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00259-010-1406-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theocharis AD, Theocharis DA, De Luca G, Hjerpe A, Karamanos NK. Compositional and structural alterations of chondroitin and dermatan sulfates during the progression of atherosclerosis and aneurysmal dilatation of the human abdominal aorta. Biochimie 2002; 84:667-74; PMID:12453639; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01428-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theocharis AD, Tsolakis I, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Chondroitin sulfate as a key molecule in the development of atherosclerosis and cancer progression. Adv Pharmacol 2006; 53:281-95; PMID:17239771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1054-3589(05)53013-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behr TM, Becker WS, Bair HJ, Klein MW, Stühler CM, Cidlinsky KP, Wittekind CW, Scheele JR, Wolf FG. Comparison of complete versus fragmented technetium-99m-labeled anti-CEA monoclonal antibodies for immunoscintigraphy in colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med 1995; 36:430-41; PMID:7884505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Cardillo TM, Chang CH, McBride WJ, Rossi EA, Horak ID, Goldenberg DM. Improving the delivery of radionuclides for imaging and therapy of cancer using pretargeting methods. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11:7109s-21s; PMID:16203810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broisat A, Hernot S, Toczek J, De Vos J, Riou LM, Martin S, Ahmadi M, Thielens N, Wernery U, Caveliers V, et al. Nanobodies targeting mouse/human VCAM1 for the nuclear imaging of atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res 2012; 110:927-37; PMID:22461363; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinojosa LE, Hernández T, de Acosta CM, Montero E, Pérez R, López-Requena A. Construction of a recombinant non-mitogenic anti-human CD3 antibody. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2010; 29:115-24; PMID:20443703; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/hyb.2009.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateo C, Moreno E, Amour K, Lombardero J, Harris W, Pérez R. Humanization of a mouse monoclonal antibody that blocks the epidermal growth factor receptor: recovery of antagonistic activity. Immunotechnology 1997; 3:71-81; PMID:9154469; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1380-2933(97)00065-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mather SJ, Ellison D. Reduction-Mediated Technetium-99m Labeling of Monoclonal Antibodies. J Nucl Med 1990; 31:692-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jellinek H, Hársing J, Füzesi S. A new model for arteriosclerosis. An electron-microscopic study of the lesions induced by i.v. administered fat. Atherosclerosis 1982; 43:7-18; PMID:7092984; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0021-9150(82)90095-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]