Abstract

Heterochromatin protein 1α (HP1α) encoded from the CBX5-gene is an evolutionary conserved protein that binds histone H3 di- or tri-methylated at position lysine 9 (H3K9me2/3), a hallmark for heterochromatin, and has an essential role in forming higher order chromatin structures. HP1α has diverse functions in heterochromatin formation, gene regulation, and mitotic progression, and forms complex networks of gene, RNA, and protein interactions. Emerging evidence has shown that HP1α serves a unique biological role in breast cancer related processes and in particular for epigenetic control mechanisms involved in aberrant cell proliferation and metastasis. However, how HP1α deregulation plays dual mechanistic functions for cancer cell proliferation and metastasis suppression and the underlying cellular mechanisms are not yet comprehensively described. In this paper we provide an overview of the role of HP1α as a new sight of epigenetics in proliferation and metastasis of human breast cancer. This highlights the importance of addressing HP1α in breast cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

Keywords: breast-cancer, metastasis; chromatin; epigenetics; histone-modifications; invasion; mitosis; proliferation

Abbreviations

- bp

base pair

- CBX

chromobox homolog

- CD

chromo domain

- CSC

cancer stem cells

- CSD

cromo shadow domain

- CTE

C-terminal extension

- DNMT

DNA-methyltransferase

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- HDMT

histone demethylase

- HMT

histone methyltransferase

- HP1

heterochromatin protein 1

- NTE

N-terminal extension

- PEV

position effect variegation

- SOMU

sumoylation

- TGS

transcriptional gene silencing

- TSS

transcriptional start site

Introduction

Modern medicine has increased breast cancer patient survival.1 This success provides encouragement to newly diagnosed individuals. However, currently available therapeutic regimens are often poorly tolerated or involve radical surgery.2,3 Because metastases are responsible for the vast majority of deaths attributed to breast cancer, it is essential to design novel strategies, capable of interfering with metastasis while causing fewer adverse effects. To prevent metastatic invasion by tumors into distal sites an improved understanding is needed of how individual proteins alter the metastatic processes in breast cancer. Heterochromatin Protein 1α (HP1α) has been referred to as a breast cancer metastasis suppressor, but the molecular mechanism for this suppression remains still relative elusive. To provide insights into the current knowledge we are hereby reviewing the role of HP1α in the development of primary breast tumors and the metastasis of these tumors to distal sites.

Epigenetics

In the nucleus, DNA coils around a histone octamer consisting of 8 histone molecules (2 copies each of: H2A, H2B, H3 and H4). The protein complex is wrapped with approximately 147 bp of DNA to form a nucleosome and these are connected through linker DNA and stabilized by the binding of the linker histone H1.4,5 In this conformation DNA condenses into chromatin. There are 2 primary forms of chromatin, euchromatin and heterochromatin, and these forms are commonly characterized to be enriched with either active or silenced genes, respectively.6 A wide array of post-translational, so called epigenetic, modifications controls the arrangement of chromatin. Such epigenetic modifications can mediate meiotically and mitotically heritable changes in gene expression and cellular phenotypes that are not controlled by the underlying DNA sequence itself.7

Central aspects of epigenetics include histone modifications, DNA-methylation and microRNAs.7,8 These different mechanisms are closely interconnected and serve to regulate gene expression. The type of epigenetic modification most directly relevant to this review is histone methylation that can generate a unique epigenetic mark specifically read by HP1 proteins. Methylation of histones can represent a mark for either gene silencing or activation and i.e. di- and tri-methylation of lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9me2/3) are considered hallmarks of transcriptional silent chromatin and hence preferentially found in heterochromatin.9 In contrast, methylation of lysine 4 of the histone H3 (H3K4me) denotes transcriptional activity and this modification is predominantly localized to the promoter region of active genes in euchromatin.9 Additions or removals of histone methyl groups are carried out by enzymes termed histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and histone demethylases (HDMTs), respectively.10,11 Aberrant activity of HMTs can lead to epigenetic silencing of critical genes for cancer progression, such as tumor suppressor genes, and is frequently observed in breast cancer.12,13

The HP1 Family – Form and Function

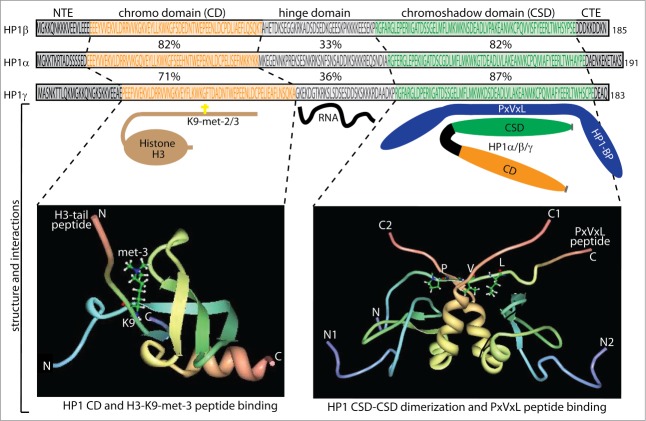

The heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family was originally identified in Drosophila melanogaster as a component of chromatin enriched at pericentric heterochromatin and implicated in the process of chromatin packing and repression of gene expression.14 In mammalian cells, the HP1 family is composed of 3 distinct but highly conserved non-histone protein homologs: HP1α, HP1β, and HP1γ (Fig. 1), encoded from the CBX5, CBX1 and CBX3 genes, respectively.15-18 The HP1 proteins are bone fide transcriptional repressors, and while it still remains relative unclear how gene expression of the individual members of the HP1 family of proteins is regulated, several key observations related to the diverse biological functions of these proteins have been reported. I.e. although all 3 HP1 proteins interact specifically with di- and tri-methylated lysine 9 on the histone H3, each HP1 protein has a different chromatin distribution. Specifically, HP1α is present mainly in heterochromatic regions, HP1β is found in both hetero- and euchromatic regions and HP1γ is primarily located in euchromatic regions.18-20 It is also described that mitotic defects occur when HP1 proteins are insufficiently expressed or improperly located within the nucleus.21-23 Important to this review, the expression level of HP1α in breast cancer cells correlates with both clinical data and clinical outcomes in this disease.24

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the HP1 domain structure. The protein domain structure is projected on the amino acid sequences of HP1α, HP1β and HP1γ with the chromo domain (CD) in orange and the chromo shadow domain (CSD) in green connected by the hinge domain. Also included are the N-terminal extension (NTE) and C-terminal extension (CTE). Percentage identity relative to HP1α is indicated between the sequences. 149 Below the diagrams are illustrated examples of key interaction partners. The CD mediates the binding of histone H3K9 di- and tri-methylated (H3K9me2/3)), the hinge mediates RNA interactions, while the CSD mediates HP1-HP1 dimerization that generates a structural platform for interaction with HP1 binding proteins (HP1-BP) including the pentapeptide motif PxVxL (x = any amino acid). Structural analyses of CD and CSD mediated protein interactions are shown in the bottom panels. The bottom panel to the left shows the 3-dimensional structure of the HP1 CD domain binding to histone H3K9 tri-methylated (Protein Data Bank code 2RSN). N- and C-terminal residues of the HP1 CD are shown together with the N- and C-terminal residues of the CD interacting H3 peptide with K9 tri-methylation. The Bottom panel to the right shows the 3-dimensional structure of the HP1 CSD domain binding to the PxVxL motif in CAF1 (Protein Data Bank code 1S4Z). N- and C-terminal residues of the 2 dimerizing HP1 CSDs are shown with numbering index 1 and 2 to distinguish the HP1 subunits. Also the N- and C-terminal residues of the CSD dimer interacting CAF1 peptide are shown with the position of the PxVxL motif indicated.

The three HP1 proteins consist of approximately 190 amino acids with a size around 22 kD and contains an N-terminal domain termed the chromo domain (CD) and a carboxy terminal domain termed the chromo shadow domain (CSD), separated by a flexible hinge domain (Fig. 1).25,26 For all 3 HP1 proteins the tethering to chromatin by the CD, CSD or heterologous DNA-binding domains mediates transcriptional repression in cis.19,27 Both the CD and CSD are highly conserved among eukaryotes with a 50–70% identity of the mammalian and Drosophila orthologous HP1 proteins, whereas the hinge region is less conserved with 25–30% identity.28 The CD, in part, associates HP1 to chromatin through specific interactions with di- and tri-methylated lysine 9 on the H3 histone tail (H3K9me2/3), where the affinity for CD binding increases proportionally with the degree of methylation.19,29,30 Structural studies have shown the formation of a pocket structure of the CD fitting with H3K9 di- and tri-methylation (Fig. 1).31,32 The CD also interacts with the tail of linker histone H1.4 methylated on lysine 26 that can further participate in chromatin compaction.33 The CSD has an amino acid sequence and structure similar to that of the CD. However, the CSD functions mainly as a dimerization domain, forming homo- and hetero-dimers with i.e., HP1 proteins themselves (Fig. 1).19,34,35 These dimers form a Y shaped interaction platform for proteins through the pentapeptide motif PxVxL (x = any amino acid) (Fig. 1).34-38 Many different types of proteins contain PxVxL motifs, and several have been shown to interact with HP1 proteins through the CSD: specific examples include TIF1α and TIF1β,17,18,39 the lamin B receptor,40 the nuclear body component SP100,41 the SUMO-specific protease SENP7,42 and the chromatin assembly factor 1 subunit p150 (CAF-1p150).43 However, there are proteins that associate with the CSD of HP1 through alternative sequence motifs, such as BRM-related gene 1 (BRG1) and pogo transposable element-derived protein with zinc finger domain (POGZ).27,44 Interaction without requirement of the PxVxL motif is also observed for suppressor of variegation 3–9 homolog 1 (SUV39h1),45 one of the best described interaction partners of HP1 proteins. The CSD also interacts with the first helix of the histone fold of H3, a region involved in chromatin remodeling.37,46,47 This H3 region is abbreviated Shadock for “chromoShadow docking” and contains a variant of the PxVxL motif, PGTVAL, required for HP1 binding and besides also capable forming interaction with BRG1.46 Efficient SWI/SNF remodeling requires this H3 contact and is inhibited in the presence of HP1 proteins. SWI/SNF ATPase activity facilitates the HP1 binding for functional detection and arrest of chromatin remodeling.48 The H3 histone fold binding of HP1 proteins is disrupted by phosphorylation at H3Y41 by JAK2 kinase and by phosphorylation at H3T45 and H3S57 by DYRK1A kinase where the latter 2 H3 modifications also showed to have influence on the competition of HP1 proteins and BRG1 for binding to the histone fold. These complex networks of H3 histone fold modifications and interactions can thereby affect HP1 chromatin association and HP1 mediated transcriptional repression independent of H3K9 methylation.48

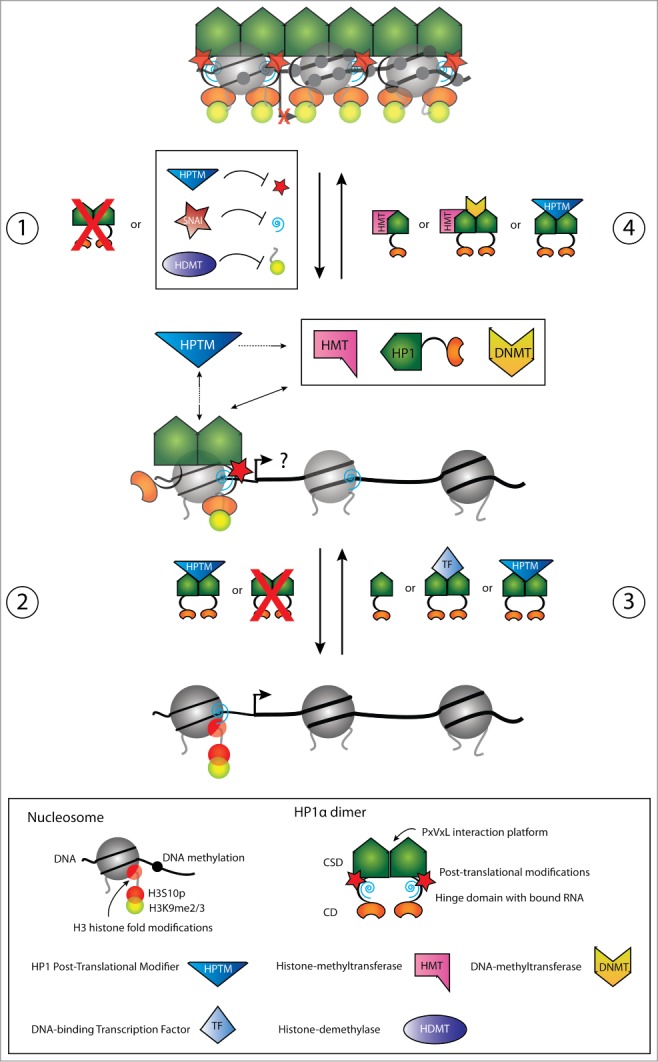

When bound to di- or tri-methylated H3K9 through the HP1 CD a subsequent recruitment of SUV39h1 causes adjacent H3K9 residues to become methylated (Fig. 2). This creates new binding sites for additional HP1 proteins that, in turn, will further recruit SUV39h1 proteins (Fig. 2, panel 4). This mechanism can explain how HP1 modulates the spread of heterochromatin into neighboring euchromatin,29,30 a phenomenon known as position effect variegation (PEV).49-51 PEV is shown to be suppressed when HP1 is deleted and enhanced when HP1 is duplicated.50,51 Moreover, HP1 proteins have been shown to directly bind DNA-methyltransferases (DNMTs) via the CSD and in complex with SUV39H1.52 These observations serve to highlight the tight interconnection between different types of epigenetic mechanisms in fine tuning of gene regulation.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of dynamics in HP1α chromatin release (panels 1 and 2) and recruitment (panels 3 and 4) for transcriptional regulation of pro-invasive genes in cancer progression and EMT. Panels 1 and 2. In non-metastatic cancer cells, pro-invasive genes are transcriptionally silenced through chromatin condensation mediated by HP1α. During initial stages of EMT, reduced HP1α chromatin binding can be mediated by down-regulation of HP1α expression, by Snail1 mediated repression of pericentric RNA transcripts, by alterations in the H3 modification code thereby inhibiting HP1α binding, or by alterations in the HP1α post-translational modification status (e.g., SUMO) (panel 1). The chromatin presence of HP1α can be further reduced by additional downregulation of HP1α expression, by alterations in the HP1α post-translational modification status, or by alterations in the H3 modification code inhibiting HP1α binding (panel 2). The result can be transcriptional activation of pro-invasive genes to different degrees enabeling the cell to metastasize. Panels 3 and 4. Conversely, transription of pro-invasive genes in metastasizing cells can be silenced by up-regulation in HP1α expression, by alterations in the H3 modification code allowing HP1α recruitment, by HP1α recruitment via interactions with DNA sequence specific transcription factors, by HP1α recruitment via interactions with RNA, or by alterations in the HP1α post-translational modification status (e.g. SUMO) (panel 3). Once chromatin bound, HP1α can further recruit chromatin modulating factors. Recruitment of HMTs causes H3 methylation in adjacent nucleosomes allowing the spread of HP1α, and the recruitment of DNMTs causes methylation of the underlying DNA (panel 4). Dynamics in HP1α post-translational modifications (e.g., SUMO) can participate in regulating maintenance of chromatin binding. This is altogether resulting in transcriptional silencing of pro-invasive genes and an epithelial-like phenotype.

The hinge region of HP1 also contributes to the HP1 association with chromatin through interactions with histone H1 and RNA, where the RNA component is thought to be important in the maintenance and localization of HP1 proteins along the chromosome.19,53-55 Recent studies have shown that HP1 proteins can be guided to the appropriate locations through complex formation with RNA and nuclear RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) proteins (e.g. Argonaute).56,57 These results suggest that HP1 together with proteins of the RNAi machinery locate in the nucleus as in transcriptional gene silencing (TGS). The mechanism of TGS is well established in Schizosaccharomyces pombe,58,59 with emerging evidence of the reality of this mechanism in mammalian cells.60,61 Interestingly, studies have shown that this mechanism is not restricted to the transcriptional activity of genes at their promoters but also at variable used exons, contributing to alternative splicing by exon inclusion or exclusion.56,57,62 Indeed, recent studies have suggested that epigenetic mechanisms not only serve to regulate gene expression, but also influence the splicing of primary RNA transcripts.63,64 This connection between epigenetics and alternative splicing was originally proposed 2 decades ago from the observation that the average exon is 140–150 bp long, a length strikingly similar to the 147 bp of DNA forming part of the nucleosomes.65 Current estimates based on deep sequencing methodologies indicate that more than 90% of human genes undergo alternative splicing, which is implicated in numerous diseases including cancer.66,67 Evidence of different mechanisms in the regulation of alternative splicing are now emerging, where histone modifications and their interaction with the non-histone proteins, such as HP1, can modulate splicing either through direct interaction with the splicing machinery,68,69 or through regulating the elongation rate by stalling of the transcribing polymerase.56,70 These observations also suggest a role for epigenetics in other RNA processing events, such as RNA cleavage and polyadenylation in the 3’-end processing of nascent mRNA, such that histone modifications could have post transcriptional effects.71

Like the individual histones, the HP1 proteins have all been shown to be subjected to a variety of post-translational modifications with impact on their function and localization to chromatin.20,55,72,73 These modifications include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation ubiquitinylation, sumoylation and formylation, which suggest the existence of an HP1-enbodied “silencing subcode” that underlines the instructions of the histone code.72,74,75 Although the specific effects of these different modifications are largely unknown, with notably exceptions that will be described below, they possibly mediate a predetermination of the vast selection of binding partners available to each HP1 protein (Fig. 2). In relation to this, affinity purification and mass spectrometry methodologies identified in a comparative analysis the number of binding partners for HP1β and HP1γ to be 30–40 for each and around 10 for HP1α, with only partial overlap.76 Note that Nozawa, et al. presented a larger set of HP1α interacting proteins.44 The possibility of individual HP1 protein-protein interaction predeterminations regulated by post-translational modifications are in accordance with the observation that the individual HP1 proteins mainly associate with a single binding partner or in small protein complexes of limited entities, rather than in large complexes including all or most of the identified binding partners.76

How Epigenetics Control Exerted by HP1α can Influence the Onset and Pathogenesis of Breast Cancer

In the field of carcinogenesis, HP1α is of importance and has been implicated in cancers originating from a remarkable diversity of tissues including lung, colon and breast.24,77,78 In contrast to HP1β and HP1γ, HP1α is described to be differentially expressed between cancerous and non-cancerous cells.24 The majority of research in this regard has been conducted in relation to breast cancer. Despite these efforts, the exact roles of HP1α in breast cancer development and metastasis remain elusive and somewhat contradictory. Here, the current HP1α literature is summarized and key incongruences regarding the roles of HP1α in breast cancer are outlined together with testable hypotheses that may resolve them.

Primary tumor cells of breast carcinomas exhibit higher expression of HP1α encoding mRNA and protein compared to normal breast tissue.24 Diverse potential cause and effect relationships between HP1α expression, putative HP1α-mediated regulation of mitosis and possible HP1α-mediated tumorigenesis are described. A role for HP1α in mitosis was postulated based on HP1α interactions with cell cycle dependent proteins18,43,79 and the demonstration that both mRNA from the CBX5-gene and HP1α protein levels diminish during transient cell cycle exit.24 Moreover, during mitosis HP1 proteins dissociate from chromosomes because of incapability to bind methylated H3K9 if the neighboring residue serine 10 is phosphorylated by Aurora B kinase (H3S10p).44,75 POGZ is required for normal mitotic progression and for correct activation and dissociation of Aurora B kinase from chromosomes during M phase. POGZ binds HP1α uniquely of the HP1 proteins and this CSD interaction destabilizes the HP1α chromatin interaction.44 Nielsen, et al. showed that HP1α interacts with TIF1β18 and Wang, et al. found that the complex mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of the tumor suppressor p53.80 Moreover, HP1α interacts with CAF-1p60 and CAF-1p150,43,81 validated markers of cellular proliferation.79 These CAF-1 proteins play a key role in de novo DNA synthesis and are required for S-phase progression in complex with HP1α.82 In the context of these observations, however, it is difficult to reconcile how HP1α can also mediate S-phase arrest through suppression of cyclin E following direct interaction with retinoblastoma protein (Rb) or via binding of SUV39h1.83 A direct link between acquired HP1α post-translational modifications and the HP1α mitotic functions was recently described.84,85 Whereas HP1α is constitutively phosphorylated at the N-terminal region, the hinge domain is preferentially phosphorylated at G2/M phase of the cell cycle. This hinge domain phosphorylated form of HP1α is specifically localized to kinetochores during early mitosis.84,85 HP1α hinge domain phosphorylation is mediated by NDR1 kinase and is required for mitotic progression and SGO1 binding to mitotic centromeres.84,85 Cells lacking NDR kinase exhibit a loss of mitosis specific HP1α phosphorylation followed by prometaphase arrest. Altogether this points to the interconnection between HP1α post-translational modifications and accurate chromosome alignment during mitotic progression.84,85 In this line the functional interaction between HP1 and BRCA1 also might be interesting.86 BRCA1 is frequently mutated in inherited breast cancer. BRCA1 maintains integrity of the genome by promoting homologous recombination DNA repair. Following DNA damage, BRCA1 plays an essential role in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M boundary. HP1 proteins are required for these BRCA1 mediated functions.86 This suggests that compromising HP1α expression could promote tumorigenesis by impairing the functions of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor.86 BRCA1 functions are in breast cancer often inactivated by other mechanisms than mutations, called BRCAness.87 If such BRCAness can be directly related to alterations in HP1α expression remains an important issue for future research. However, with respect to the higher observed expression of HP1α in primary tumor cells compared to normal tissue, another pair of findings failed to show a dominant role for HP1α in proliferation. Specifically, De Koning, et al. and Norwood, et al. observed no changes in cancer cell proliferation following RNAi knockdown of HP1α.24,88 In light of their observations, De Koning, et al. proposed a novel hypothesis: increased proliferation of tumorigenic cells is accompanied by HP1α expression primarily to ensure faithful mitosis and correct chromosome segregation that could provide a selective advantage to cancer cells given their less efficient mitotic checkpoints.89 Hopefully, future studies will reveal the roles of HP1α in cancer cells in order to explain the differential expression between primary tumor and normal tissue.

The relationships between HP1α and the invasive potential of cancer cells have been carefully addressed in recent years. HP1α was linked to a higher invasive potential of cancer cells when it was found to be down-regulated in metastatic cells of colon cancer and thyroid carcinomas relative to non-metastatic cells.78,90 In breast cancer, HP1α has also been shown to be downregulated at the mRNA and protein level in highly invasive breast cancer cell lines (e.g., HS578T and MDA-MB-231) compared to poorly invasive breast cancer cell lines (e.g. T47D and MCF7) while HP1β and HP1γ were equally expressed.91-93 Immunohistochemistry observations from in vivo samples showed that HP1α expression was reduced in cells from metastases relative to the primary tumor in the breast corroborating these findings.92 Alterations in the invasive potential of well characterized breast cancer cell lines were used to confirm these findings via direct functional analyses in the absence of any alterations in proliferation rate.66,70 Poorly invasive MCF7 cells have an approximate 40% increase in their invasive potential following RNAi-mediated knockdown of HP1α expression and highly invasive MDA-MB-231 cells lost up to 50% of their invasive potential when following either transfection or transduction with a HP1α-expression vector.88,92 Based on these data, HP1α has now been characterized as a metastasis suppressor,88,92 which in contrast to tumor suppressors are defined as being able to suppress metastasis without affecting the growth of the tumor.94 On the surface it seems contradictory that up-regulation of HP1α correlates with increased cell proliferation of the primary tumor and poorer clinical prognosis while down-regulation of HP1α contributes to a tumor cell's invasive potential during carcinogenesis. Closer inspection suggests that these observations constitute primary examples of the global inverse correlation that exists between cancer cell proliferation and invasion.24,95 Within this paradigm, acquisition of an invasive phenotype is frequently incompatible with high proliferation rates. Thus, a temporal slowdown in the proliferation of tumor cells that is accompanied by a lower expression of HP1α might be the combination of conditions necessary to promote the expression of pro-invasive genes and hence metastasis (Fig. 2).

The observed correlation between HP1α expression and invasive potential has inspired the hypothesis that HP1α may directly be involved in the silencing of genes that potentiate cancer cell invasive potential and metastasis i.e. genes involved in the developmental program of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Fig. 2).92 Furthermore, the inverse correlation between proliferation and invasive potential suggests a role for HP1α in the formation and function of cancer stem cells (CSC). CSC are a subpopulation of cancer cells that fuel tumor growth because, like normal adult stem cells i.e., haematopoietic stem cells, CSC are endowed with self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation capacities.96 Particularly relevant here is the knowledge that differentiated blood lymphocytes have lower expression of all 3 HP1 proteins compared to their less differentiated progenitor cells97,98 and that HP1 proteins are important for maintaining the transcriptional integrity of haematopoietic stem cells through interactions with TIF1β.99 Given the high degree of similarity between CSC and normal adult stem cells, a corollary to these data is that HP1α may play a critical role in maintaining the “stemness” of CSC. Originally identified in haematopoietic malignancies,100 CSC has now been identified in a broad spectrum of solid tumors where they produce important mediators of tumor growth, promote local tumor invasion and facilitate metastasis formation.101-103 Moreover, increasing evidence suggest that the CSC compartment itself is a heterogeneous mix of distinct CSC subpopulations (e.g., migrating vs. non-migrating CSC),104-106 much like normal adult circulating stem cells vs. normal adult tissue-residing stem cells.107,108 Thus, the different expression levels of HP1α between primary tumor and metastases could be reflecting, at least in part, the presence of distinct CSC subpopulations at the sites of analyses. Fully understanding the contributions of different CSC subpopulations within any given HP1α analyses is critical to accurately interpreting molecular insights regarding epigenetic contributions of HP1α in the transcriptional regulation of tumorigenesis, proliferation and invasive potential.

Recent evidences implicate HP1α in the EMT process (reviewed in ref. 109) occurring at the initial stages of metastasis. The Snail1 transcription factor has an essential role in triggering EMT both during embryogenesis and in cancer.110 Snail1 can repress pericentromeric transcription through the H3K4 deaminase LOXL2.111 Millanes-Romero, et al. demonstrated that HP1α association to major satellite repeat sequences located in pericentric heterochromatin decreased during the initial steps of TGFβ-induced EMT.111 This effect was shown to be because of a Snail1-dependent transient release of HP1α proteins from pericentric heterochromatin, rather than an effect due to transcriptional downregulation of HP1α encoding mRNA from the CBX5-gene. Thus, a HP1α release from chromatin is probably necessary to permit the heterochromatin reorganization occurring during EMT.111 Since HP1α association to pericentric heterochromatin requires RNA components derived from these sites the results are consistent with an underlying Snail1 mediated down-regulation of such heterochromatic derived transcripts (Fig. 2, panel 1).111 Other means such as histone modifications and HP1α post-translational modifications could participate in HP1α dynamics in heterochromatin association in EMT (Fig. 2). In this line it is important to note that Maison, et al. described that HP1α sumoylation in the hinge domain promoted de novo HP1α targeting to pericentric heterochromatin through interactions with pericentric heterochromatin derived RNA and accordingly could participate in seeding further HP1α localization.55 A recent report has specifically addressed the important link between HP1α sumoylation, heterochromatin remodeling and EMT.42 The SENP7 SUMO-specific protease is involved in breast cancer progression and interacts with the HP1α CSD through a PxVxL motif.42,112 Sumoylated HP1α is enriched at, and silences, E2F-responsive and mesenchymal gene promoters (i.e. the EMT mesenchymal-marker vimentin) in poorly invasive epithelial cells.42 Elevated SENP7 levels mediate an HP1α hypo-sumoylation, which abolish the silencing of these E2F-responsive and mesenchymal gene promoters, and concordantly is involved in acquisition of the EMT-like phenotype.42 A putative not yet solved underlying complexity for the SENP7 and HP1α association to mediate gene regulated is illustrated by Maison, et al. finding that SENP7 mediated de-conjugation of HP1α sumoylation can be involved in retention of the initial targeted sumoylated HP1α to pericentric heterochromatin (Fig. 2).112 However, the facts that both HP1α expression level and the distribution of HP1α through post-translational modifications are of importance in breast cancer related EMT suggests caution using absolute HP1α expression levels, mRNA and protein, as a prognostic value in future breast cancer diagnostic procedures. Instead development of measurements of the functional HP1α amounts in relation to metastasis suppression will be more informative.

Whereas many studies have focused on HP1α pericentric heterochromatin associations, HP1α also clearly has importance for regulation of euchromatic localized genes exemplified by the involvement in regulation of E2F-responsive genes. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) sequence data produced by LeRoy, et al.113 revealed that only 2% of the total cellular HP1α molecules are actually associated with gene promoters, 25% are associated within the gene bodies, while the remaining HP1α is located in intergenic regions . For such reason, the conclusion that HP1α is a facilitator of a cellular pro-invasive gene transcription program may describe only a relatively small fraction of the HP1α functions in epigenetic regulation. Because a major fraction of the gene-associated HP1α is present within gene bodies and not at the promoter, it is also plausible that a primary, but not yet well described function for HP1α in gene regulation is the potential role in regulation of RNA processing i.e., alternative splicing as discussed above. Indeed both tumor progression and EMT are highly influenced by the alternative splicing of a vast number of mRNAs.114-116 It is very intriguing that HP1α can be involved in a migratory EMT-like pathway mediated by alternative splicing besides the more conventional transcriptional repression function either in parallel or in a functional collaboration with the well-defined direct effects of Slug, Snail, Twist, ZEB1 and ZEB2 for transcriptional regulation under EMT.117 The functional consequences of alternative splicing for EMT are well illustrated by the drastic isoform changes of CD44, which have been repeatedly linked to metastasis formation.118,119 Brown, et al. recently showed that an ESRP1-mediated shift from CD44 expression from variant isoforms (CD44v) to the standard isoforms was necessary for cells to undergo complete EMT.120 Interestingly, the overall level of total CD44 protein did not change significantly during this process. These observations impose another layer of complexity and emphasize that EMT is a broad concept with multiple cross-talking signaling pathways occurring in parallel. Whether HP1α plays a role in any of these classical EMT pathways or has EMT-independent mechanisms of generating an invasive phenotype of cancer cells, is urgently needed be addressed in more comprehensive studies investigating i.e. the genomic distribution of HP1α and the gene regulatory repertoire in human cells to identify cancer relevant genes regulated by HP1α.

Genetic Regulation of CBX5 Transcription

Because of the inverse correlation between HP1α expression and the invasive potential of breast cancer cells, understanding the differential regulation of the HP1α encoding gene, CBX5, has been of great interest. Initial studies of the differential regulation of CBX5 found no change in the DNA sequence or methylation status between the poorly invasive MCF7 and highly invasive mesenchymal-like MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines.121 Thus, studies concerning the differential regulation of CBX5 have mainly focused on cis- and trans-acting elements of the promoter region, from which numerous transcription factor binding sites have been identified (e.g. YY1, E2F, and E-box elements).93,121,122 The significance of these cis- and trans-acting elements were investigated by transient reporter assays, conducted using plasmid constructs containing different insert fragments of the promoter region with various deletions of the transcription factor binding sites in well-defined breast cancer cell lines.121,122 Deletion of one specific MYC element resulted in an upregulation of CBX5 mRNA expression in the highly invasive MDA-MB-231 cells.121 In contrast, deletion of the YY1 binding sites resulted in a downregulation of CBX5 in the poorly invasive MCF7 cells.122 This result was further validated by RNAi mediated knockdown of YY1 in MCF7 cells that resulted in a down-regulation of CBX5 mRNA. Furthermore, forced up-regulation of YY1 by transfection decreased the invasive potential of highly invasive HS578T cells.122 This latter effect, however, was independent of HP1α expression, suggesting that YY1 might contribute to the regulation of CBX5 but cannot fully account for the different levels of HP1α expression and the correlation with invasive potential. ChIP experiments have demonstrated the presence of E2F proteins at the CBX5 promoter123,124 but RNAi-mediated knockdown of different E2F transcription factors in both MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells only resulted in minor changes of CBX5 mRNA expression.93

Located immediately upstream (589 bp) of the CBX5 transcriptional start site (TSS) is the divergently transcribed hnRNPA1-gene. Such “head-to-head” gene arrangements are found at a surprisingly high frequency throughout the genome, with as much more than 10% of the protein-coding genes being located on opposite strands with TSSs less than 1 kb away from each other.125-127 This bi-directional arrangement is a conserved feature among many species suggesting an ancient ancestral origin of functional importance.128-130 Interestingly, this distinct subgroup of bi-directional promoters share several features besides the head-to-head configuration separating them from other promoters.131 Bi-directional promoters are shown to have a higher frequency of CpG islands than other promoters, and consequently have a higher GC content.128-130 Furthermore, the relative presence of canonical TATA box elements is significantly less for bi-directional promoters.126,132 Finally, bi-directional promoters display an enriched occurrence of specific transcription factor binding sites, including MYC, E2F, NRF and YY1.133 Given that the CBX5 promoter lacks TATA box elements and contains a CpG island121 in addition to the close proximity of hnRNPA1 promoter and presence of the specific enriched transcription factor binding sites, it is evident that CBX5 is a signature representative of bi-directional promoter containing genes. Whereas CBX5 is down-regulated in highly invasive breast cancer cell lines, compared to poorly invasive breast cancer cell lines, the hnRNPA1-gene is evenly expressed in both types of cell lines.92,121,122 Therefore, despite the close proximity between their transcriptional start sites, the 2 genes have been thought to be independently regulated.92,121,122 However, bi-directional promoters are shown to possess several features of regulatory dependence within their shared promoter region. This dependence is illustrated by the observations that promoter activity can be altered by deletion of the opposing TSS.126 Similarly, loss of specific promoter elements of bi-directional promoters was shown to affect the transcriptional activity in both directions, suggesting that most bi-directional promoters share at least some regulatory elements.126,134 Therefore, an element affecting the transcriptional activity of CBX5 would also have potential to affect the activity of hnRNPA1. RNAi mediated knockdown of YY1 had impact on CBX5 expression whereas hnRNPA1 expression was unaffected.122 But the majority of examined cis-elements in the promoter of CBX5 have not been thoroughly investigated for their potential effects on the transcriptional regulation of hnRNPA1. A shared effect for CBX5 and hnRNPA1 transcription would indicate that the 2 promoters are not independently transcribed, which suggests that the reason for the differential expression of CBX5 in breast cancer cells is not solely controlled at the promoter level, but likely involves downstream regulatory elements or a regulatory mechanism not yet identified in this context. One possibility for the cell to disconnect transcription of CBX5 and hnRNPA1 is the use of a downstream CBX5 alternative promoter. Inspection of the ENCODE regulatory datasets for the CBX5 and hnRNPA1 bi-directional promoter in the UCSC Genome Browser, as well as published ChIP data, shows presence of poised RNA polymerase II downstream both the CBX5 and hnRNPA1 transcriptional start sites.135 For CBX5 2 RNA polymerase II peaks are present, one 50 bp downstream the bi-directional promoter and the other 400 bp further downstream.135 The latter peak was proposed to be a result of presence of an alternative transcriptional start site. Toward this point, Thliveris, et al. recently identified an alternative promoter located several kb downstream in CBX5 in mice.136 Transcription from this downstream promoter results in 2 additional HP1α encoding transcripts both containing the entire full-length coding region, but with an alternative first exon not included in the nascent transcript. However, regulation of CBX5 was concluded to be restricted to the nascent upstream promoter, since the alternative promoter transcripts only constituted a very minor contribution of protein coding mRNA. However, it should not be ruled out that dependence on this alternative promoter during CBX5 transcription could be dictated by anatomical location, different stages of cell cycle or developmental stages of embryogenesis. In this line, Thliveris, et al. further emphasized the potential significance of the alternative promoter, based upon the observation of a high degree of mammalian sequence conservation of the region corresponding to the alternative promoter.136 In addition to the region corresponding to the alternative promoter, 5 other highly conserved noncoding regions of unknown function were observed in the long first intron of the mouse CBX5 gene. This observation suggests additional regulatory elements to be involved in CBX5 regulation. A gene that has received much attention in breast cancer research and again worth mentioning in this context is BRCA1 with a bidirectional promoter much like CBX5. The BRCA1 promoter possesses the classical features of bidirectional promoters including; located head-to-head to the divergently transcribed NBR2 gene with a shared promoter of less than 500 bp in length,137 contains a CpG island,138 and bound by NRF and E2F transcription factors.139,140 Interestingly, recent studies investigating the regulation of the BRCA1 promoter have identified gene loop structures with intron sequences.141 Gene loops are transient structures formed by juxtaposition of the promoter and terminator region142–144 that can contribute to transcriptional regulation by facilitating the re-cycling of the polymerase144–146 and enhance transcriptional directionality.147 If the bi-directional hnRNPA1 and CBX5 promoter structure also uses gene loop structures for fine tuning of transcriptional regulation will be an intriguing question for future analyses by chromosome conformation methodologies.148

Conclusion

When considered together, the now gained data for HP1α expression and function point toward pivotal roles for HP1α in breast cancer proliferation and metastasis. The role and function of the higher level of HP1α expression observed in primary breast cancer tumors compared to normal tissue remain largely unknown and speculative. Here we call attention to the possibility of HP1α governing stem cell properties of different CSC subpopulations. We propose that HP1α serves to maintain the transcriptional integrity of non-migratory CSC. Thus, a high expression of HP1α in primary tumors of breast cancers could illustrate a dense population of non-migratory CSC. In turn, an intermediate range of HP1α expression could permit the expression or alternative splicing of pro-invasive genes and acquirement of an EMT-like phenotype while maintaining “stemness” properties, thus giving rise to migrating CSC. The reviewed data further indicates that transcription of pro-invasive genes or alternative transcript isoforms not only are dependent on the absolute HP1α expression level, but also on a complex network of post-translational modifications of HP1α proteins and epigenetic histone modifications. Understanding these modifications as well as the differential regulation of HP1α could help resolve some of the ambiguities described above. Despite much effort, little progress has been made in understanding the observed differential regulation of CBX5 expression during breast cancer progression. History dictates genes to be perceived as linear entities confined by promoters and terminators that determine where transcription starts and ends. Hence, studies concerning the regulation of CBX5 have been restricted to the promoter region. However, recent evidence of functional and structural relationship between the promoter, intron, exon and terminator sequences, suggests that some genes function, at least partially, as closed circuits. Because of the bi-directionally promoter composition of the, in breast cancer cells, differentially expressed CBX5 gene and the constitutively expressed hnRNPA1 gene, the transcriptional activity of the 2 genes is likely to be similar affected by trans-factors acting within the shared promoter region. Therefore, we propose novel mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of CBX5 in addition to the promoter region mediated regulation.

The data and hypotheses presented in this review highlight the need for future studies focused on the role of deregulated CBX5 expression and HP1α protein functions in the development and progression of breast cancer. Not only will such studies contribute to our general mechanistic understanding of epigenetic gene regulation, but ultimately also be of benefit for future diagnostics and prognostics of breast cancer and hopefully contribute to the prevention, or even reversal, of metastases.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Paul W. Denton for helpful discussions and advice as well as a careful review of this paper.

References

- 1. Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F, Lutz JM, De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Baili P, Rachet B, Gatta G, Hakulinen T, et al. Cancer survival in five continents: a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD). Lancet Oncol 2008; 9:730-56; PMID:18639491; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:1101-9; PMID:21300931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, Esserman LJ, Grunfeld E, Halberg F, Hantel A, Henry NL, Muss HB, Smith TJ, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:961-5; PMID:23129741; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luger K, Richmond TJ. The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1998; 8:140-6; PMID:9610403; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell 1999; 98:285-94; PMID:10458604; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81958-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004; 429:457-63; PMID:15164071; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev 2009; 23:781-3; PMID:19339683; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1787609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santos-Reboucas CB, Pimentel MM. Implication of abnormal epigenetic patterns for human diseases. Eur J Hum Genet 2007; 15:10-7; PMID:17047674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lachner M, Jenuwein T. The many faces of histone lysine methylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002; 14:286-98; PMID:12067650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00335-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang SM, Schurter BT, Aswad DW, Stallcup MR. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science 1999; 284:2174-7; PMID:10381882; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O'Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, Schmid M, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Ponting CP, Allis CD, et al. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 2000; 406:593-9; PMID:10949293; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35020506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell 2007; 128:683-92; PMID:17320506; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stearns V, Zhou Q, Davidson NE. Epigenetic regulation as a new target for breast cancer therapy. Cancer Invest 2007; 25:659-65; PMID:18058459; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/07357900701719234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. James TC, Elgin SC. Identification of a nonhistone chromosomal protein associated with heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster and its gene. Mol Cell Biol 1986; 6:3862-72; PMID:3099166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh PB, Miller JR, Pearce J, Kothary R, Burton RD, Paro R, James TC, Gaunt SJ. A sequence motif found in a Drosophila heterochromatin protein is conserved in animals and plants. Nucleic Acids Res 1991; 19:789-94; PMID:1708124; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/19.4.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saunders WS, Chue C, Goebl M, Craig C, Clark RF, Powers JA, Eissenberg JC, Elgin SC, Rothfield NF, Earnshaw WC. Molecular cloning of a human homologue of Drosophila heterochromatin protein HP1 using anti-centromere autoantibodies with anti-chromo specificity. J Cell Sci 1993; 104(Pt 2):573-82; PMID:8505380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Le Douarin B, Nielsen AL, Garnier JM, Ichinose H, Jeanmougin F, Losson R, Chambon P. A possible involvement of TIF1 alpha and TIF1 beta in the epigenetic control of transcription by nuclear receptors. EMBO J 1996; 15:6701-15; PMID:8978696 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nielsen AL, Ortiz JA, You J, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Khechumian R, Gansmuller A, Chambon P, Losson R. Interaction with members of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family and histone deacetylation are differentially involved in transcriptional silencing by members of the TIF1 family. EMBO J 1999; 18:6385-95; PMID:10562550; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nielsen AL, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Ortiz JA, Remboutsika E, Chambon P, Losson R. Heterochromatin formation in mammalian cells: interaction between histones and HP1 proteins. Mol Cell 2001; 7:729-39; PMID:11336697; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00218-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Minc E, Allory Y, Worman HJ, Courvalin JC, Buendia B. Localization and phosphorylation of HP1 proteins during the cell cycle in mammalian cells. Chromosoma 1999; 108:220-34; PMID:10460410; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004120050372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Auth T, Kunkel E, Grummt F. Interaction between HP1alpha and replication proteins in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res 2006; 312:3349-59; PMID:16950245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inoue A, Hyle J, Lechner MS, Lahti JM. Perturbation of HP1 localization and chromatin binding ability causes defects in sister-chromatid cohesion. Mutation Res 2008; 657:48-55; PMID:18790078; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serrano A, Rodriguez-Corsino M, Losada A. Heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) proteins do not drive pericentromeric cohesin enrichment in human cells. PloS One 2009; 4:e5118; PMID:19352502; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0005118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Koning L, Savignoni A, Boumendil C, Rehman H, Asselain B, Sastre-Garau X, Almouzni G. Heterochromatin protein 1alpha: a hallmark of cell proliferation relevant to clinical oncology. EMBO Mol Med 2009; 1:178-91; PMID:20049717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/emmm.200900022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paro R, Hogness DS. The Polycomb protein shares a homologous domain with a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88:263-7; PMID:1898775; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.88.1.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aasland R, Stewart AF. The chromo shadow domain, a second chromo domain in heterochromatin-binding protein 1, HP1. Nucleic Acids Res 1995; 23:3168-73; PMID:7667093; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/23.16.3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nielsen AL, Sanchez C, Ichinose H, Cervino M, Lerouge T, Chambon P, Losson R. Selective interaction between the chromatin-remodeling factor BRG1 and the heterochromatin-associated protein HP1alpha. EMBO J 2002; 21:5797-806; PMID:12411497; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/cdf560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hiragami K, Festenstein R. Heterochromatin protein 1: a pervasive controlling influence. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005; 62:2711-26; PMID:16261261; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-005-5287-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lachner M, O'Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature 2001; 410:116-20; PMID:11242053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35065132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 2001; 410:120-4; PMID:11242054; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35065138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nielsen PR, Nietlispach D, Mott HR, Callaghan J, Bannister A, Kouzarides T, Murzin AG, Murzina NV, Laue ED. Structure of the HP1 chromodomain bound to histone H3 methylated at lysine 9. Nature 2002; 416:103-7; PMID:11882902; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jacobs SA, Khorasanizadeh S. Structure of HP1 chromodomain bound to a lysine 9-methylated histone H3 tail. Science 2002; 295:2080-3; PMID:11859155; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1069473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Daujat S, Zeissler U, Waldmann T, Happel N, Schneider R. HP1 binds specifically to Lys26-methylated histone H1.4, whereas simultaneous Ser27 phosphorylation blocks HP1 binding. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:38090-5; PMID:16127177; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C500229200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brasher SV, Smith BO, Fogh RH, Nietlispach D, Thiru A, Nielsen PR, Broadhurst RW, Ball LJ, Murzina NV, Laue ED. The structure of mouse HP1 suggests a unique mode of single peptide recognition by the shadow chromo domain dimer. EMBO J 2000; 19:1587-97; PMID:10747027; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cowieson NP, Partridge JF, Allshire RC, McLaughlin PJ. Dimerisation of a chromo shadow domain and distinctions from the chromodomain as revealed by structural analysis. Curr Biol 2000; 10:517-25; PMID:10801440; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00467-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thiru A, Nietlispach D, Mott HR, Okuwaki M, Lyon D, Nielsen PR, Hirshberg M, Verreault A, Murzina NV, Laue ED. Structural basis of HP1/PXVXL motif peptide interactions and HP1 localisation to heterochromatin. EMBO J 2004; 23:489-99; PMID:14765118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richart AN, Brunner CI, Stott K, Murzina NV, Thomas JO. Characterization of chromoshadow domain-mediated binding of heterochromatin protein 1alpha (HP1alpha) to histone H3. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:18730-7; PMID:22493481; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.337204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mendez DL, Mandt RE, Elgin SC. Heterochromatin Protein 1a (HP1a) partner specificity is determined by critical amino acids in the chromo shadow domain and C-terminal extension. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:22315-23; PMID:23793104; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.468413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Le Douarin B, You J, Nielsen AL, Chambon P, Losson R. TIF1alpha: a possible link between KRAB zinc finger proteins and nuclear receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1998; 65:43-50; PMID:9699856; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-0760(97)00175-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ye Q, Callebaut I, Pezhman A, Courvalin JC, Worman HJ. Domain-specific interactions of human HP1-type chromodomain proteins and inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:14983-9; PMID:9169472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Seeler JS, Marchio A, Sitterlin D, Transy C, Dejean A. Interaction of SP100 with HP1 proteins: a link between the promyelocytic leukemia-associated nuclear bodies and the chromatin compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:7316-21; PMID:9636146; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bawa-Khalfe T, Lu LS, Zuo Y, Huang C, Dere R, Lin FM, Yeh ET. Differential expression of SUMO-specific protease 7 variants regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:17466-71; PMID:23045645; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1209378109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murzina N, Verreault A, Laue E, Stillman B. Heterochromatin dynamics in mouse cells: interaction between chromatin assembly factor 1 and HP1 proteins. Mol Cell 1999; 4:529-40; PMID:10549285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80204-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nozawa RS, Nagao K, Masuda HT, Iwasaki O, Hirota T, Nozaki N, Kimura H, Obuse C. Human POGZ modulates dissociation of HP1alpha from mitotic chromosome arms through Aurora B activation. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:719-27; PMID:20562864; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamamoto K, Sonoda M. Self-interaction of heterochromatin protein 1 is required for direct binding to histone methyltransferase, SUV39H1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 301:287-92; PMID:12565857; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)03021-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lavigne M, Eskeland R, Azebi S, Saint-Andre V, Jang SM, Batsche E, Fan HY, Kingston RE, Imhof A, Muchardt C. Interaction of HP1 and Brg1/Brm with the globular domain of histone H3 is required for HP1-mediated repression. PLoS Genet 2009; 5:e1000769; PMID:20011120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dawson MA, Bannister AJ, Gottgens B, Foster SD, Bartke T, Green AR, Kouzarides T. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature 2009; 461:819-22; PMID:19783980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jang SM, Azebi S, Soubigou G, Muchardt C. DYRK1A phoshorylates histone H3 to differentially regulate the binding of HP1 isoforms and antagonize HP1-mediated transcriptional repression. EMBO Rep 2014; 15:686-94; PMID:24820035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wallrath LL. Unfolding the mysteries of heterochromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1998; 8:147-53; PMID:9610404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eissenberg JC, James TC, Foster-Hartnett DM, Hartnett T, Ngan V, Elgin SC. Mutation in a heterochromatin-specific chromosomal protein is associated with suppression of position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:9923-7; PMID:2124708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eissenberg JC, Morris GD, Reuter G, Hartnett T. The heterochromatin-associated protein HP-1 is an essential protein in Drosophila with dosage-dependent effects on position-effect variegation. Genetics 1992; 131:345-52; PMID:1644277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fuks F, Hurd PJ, Deplus R, Kouzarides T. The DNA methyltransferases associate with HP1 and the SUV39H1 histone methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:2305-12; PMID:12711675; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkg332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maison C, Bailly D, Peters AH, Quivy JP, Roche D, Taddei A, Lachner M, Jenuwein T, Almouzni G. Higher-order structure in pericentric heterochromatin involves a distinct pattern of histone modification and an RNA component. Nat Genet 2002; 30:329-34; PMID:11850619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Muchardt C, Guilleme M, Seeler JS, Trouche D, Dejean A, Yaniv M. Coordinated methyl and RNA binding is required for heterochromatin localization of mammalian HP1alpha. EMBO Rep 2002; 3:975-81; PMID:12231507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maison C, Bailly D, Roche D, Montes de Oca R, Probst AV, Vassias I, Dingli F, Lombard B, Loew D, Quivy JP, et al. SUMOylation promotes de novo targeting of HP1alpha to pericentric heterochromatin. Nat Genet 2011; 43:220-7; PMID:21317888; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Allo M, Buggiano V, Fededa JP, Petrillo E, Schor I, de la Mata M, Agirre E, Plass M, Eyras E, Elela SA, et al. Control of alternative splicing through siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16:717-24; PMID:19543290; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ameyar-Zazoua M, Rachez C, Souidi M, Robin P, Fritsch L, Young R, Morozova N, Fenouil R, Descostes N, Andrau JC, et al. Argonaute proteins couple chromatin silencing to alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012; 19:998-1004; PMID:22961379; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Verdel A, Jia S, Gerber S, Sugiyama T, Gygi S, Grewal SI, Moazed D. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science 2004; 303:672-6; PMID:14704433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1093686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zaratiegui M, Castel SE, Irvine DV, Kloc A, Ren J, Li F, de Castro E, Marin L, Chang AY, Goto D, et al. RNAi promotes heterochromatic silencing through replication-coupled release of RNA Pol II. Nature 2011; 479:135-8; PMID:22002604; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gullerova M, Proudfoot NJ. Convergent transcription induces transcriptional gene silencing in fission yeast and mammalian cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012; 19:1193-201; PMID:23022730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reuter M, Berninger P, Chuma S, Shah H, Hosokawa M, Funaya C, Antony C, Sachidanandam R, Pillai RS. Miwi catalysis is required for piRNA amplification-independent LINE1 transposon silencing. Nature 2011; 480:264-7; PMID:22121019; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Saint-Andre V, Batsche E, Rachez C, Muchardt C. Histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1gamma favor inclusion of alternative exons. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18:337-44; PMID:21358630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Allemand E, Batsche E, Muchardt C. Splicing, transcription, and chromatin: a menage a trois. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2008; 18:145-51; PMID:18372167; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 2011; 144:16-26; PMID:21215366; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Beckmann JS, Trifonov EN. Splice junctions follow a 205-base ladder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88:2380-3; PMID:2006175; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. RNA and disease. Cell 2009; 136:777-93; PMID:19239895; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet 2008; 40:1413-5; PMID:18978789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sims RJ, 3rd, Millhouse S, Chen CF, Lewis BA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Manley JL, Reinberg D. Recognition of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 facilitates the recruitment of transcription postinitiation factors and pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell 2007; 28:665-76; PMID:18042460; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Luco RF, Pan Q, Tominaga K, Blencowe BJ, Pereira-Smith OM, Misteli T. Regulation of alternative splicing by histone modifications. Science 2010; 327:996-1000; PMID:20133523; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1184208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Batsche E, Yaniv M, Muchardt C. The human SWI/SNF subunit Brm is a regulator of alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2006; 13:22-9; PMID:16341228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou HL, Luo G, Wise JA, Lou H. Regulation of alternative splicing by local histone modifications: potential roles for RNA-guided mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42:701-13; PMID:24081581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lomberk G, Bensi D, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Urrutia R. Evidence for the existence of an HP1-mediated subcode within the histone code. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8:407-15; PMID:16531993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao T, Heyduk T, Eissenberg JC. Phosphorylation site mutations in heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) reduce or eliminate silencing activity. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:9512-8; PMID:11121421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M010098200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. LeRoy G, Weston JT, Zee BM, Young NL, Plazas-Mayorca MD, Garcia BA. Heterochromatin protein 1 is extensively decorated with histone code-like post-translational modifications. Mol Cell Proteomics 2009; 8:2432-42; PMID:19567367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.M900160-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nishibuchi G, Nakayama JI. Biochemical and structural properties of heterochromatin protein 1: understanding its role in chromatin assembly. J Biochem 2014; PMID:24825911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rosnoblet C, Vandamme J, Volkel P, Angrand PO. Analysis of the human HP1 interactome reveals novel binding partners. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 413:206-11; PMID:21888893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yu YH, Chiou GY, Huang PI, Lo WL, Wang CY, Lu KH, Yu CC, Alterovitz G, Huang WC, Lo JF, et al. Network biology of tumor stem-like cells identified a regulatory role of CBX5 in lung cancer. Sci Rep 2012; 2:584; PMID:22900142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. De Lange R, Burtscher H, Jarsch M, Weidle UH. Identification of metastasis-associated genes by transcriptional profiling of metastatic versus non-metastatic colon cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res 2001; 21:2329-39; PMID:11724290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Polo SE, Theocharis SE, Klijanienko J, Savignoni A, Asselain B, Vielh P, Almouzni G. Chromatin assembly factor-1, a marker of clinical value to distinguish quiescent from proliferating cells. Cancer Res 2004; 64:2371-81; PMID:15059888; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wang C, Ivanov A, Chen L, Fredericks WJ, Seto E, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Chen J. MDM2 interaction with nuclear corepressor KAP1 contributes to p53 inactivation. EMBO J 2005; 24:3279-90; PMID:16107876; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Quivy JP, Roche D, Kirschner D, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Almouzni G. A CAF-1 dependent pool of HP1 during heterochromatin duplication. EMBO J 2004; 23:3516-26; PMID:15306854; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Quivy JP, Gerard A, Cook AJ, Roche D, Almouzni G. The HP1-p150/CAF-1 interaction is required for pericentric heterochromatin replication and S-phase progression in mouse cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008; 15:972-9; PMID:19172751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nielsen SJ, Schneider R, Bauer UM, Bannister AJ, Morrison A, O'Carroll D, Firestein R, Cleary M, Jenuwein T, Herrera RE, et al. Rb targets histone H3 methylation and HP1 to promoters. Nature 2001; 412:561-5; PMID:11484059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35087620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Chakraborty A, Prasanth KV, Prasanth SG. Dynamic phosphorylation of HP1alpha regulates mitotic progression in human cells. Nat Commun 2014; 5:3445; PMID:24619172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chakraborty A, Prasanth SG. Phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle of HP1alpha governs accurate mitotic progression. Cell cycle 2014; 13:1663-70; PMID:24786771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.29065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lee YH, Kuo CY, Stark JM, Shih HM, Ann DK. HP1 promotes tumor suppressor BRCA1 functions during the DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:5784-98; PMID:23589625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Turner N, Tutt A, Ashworth A. Hallmarks of 'BRCAness' in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4:814-9; PMID:15510162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Norwood LE, Moss TJ, Margaryan NV, Cook SL, Wright L, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJ, Kirschmann DA, Wallrath LL. A requirement for dimerization of HP1Hsalpha in suppression of breast cancer invasion. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:18668-76; PMID:16648629; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M512454200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. Decoding the links between mitosis, cancer, and chemotherapy: The mitotic checkpoint, adaptation, and cell death. Cancer Cell 2005; 8:7-12; PMID:16023594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tretiakova MS, Bond SD, Wheeler D, Contreras A, Kocherginsky M, Kroll TG, Hale TK. Heterochromatin protein 1 expression is reduced in human thyroid malignancy. Lab Invest 2014. 94(7):788-95; PMID:24840329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/labinvest.2014.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Nieva DR, Mariano EA, Hendrix MJ. Differentially expressed genes associated with the metastatic phenotype in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999; 55:127-36; PMID:10481940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1006188129423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kirschmann DA, Lininger RA, Gardner LM, Seftor EA, Odero VA, Ainsztein AM, Earnshaw WC, Wallrath LL, Hendrix MJ. Down-regulation of HP1Hsalpha expression is associated with the metastatic phenotype in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2000; 60:3359-63; PMID:10910038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Thomsen R, Christensen DB, Rosborg S, Linnet TE, Blechingberg J, Nielsen AL. Analysis of HP1alpha regulation in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 2011; 50:601-13; PMID:21374739; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mc.20755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Debies MT, Welch DR. Genetic basis of human breast cancer metastasis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2001; 6:441-51; PMID:12013533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1014739131690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Berglund P, Landberg G. Cyclin e overexpression reduces infiltrative growth in breast cancer: yet another link between proliferation control and tumor invasion. Cell Cycle 2006; 5:606-9; PMID:16582601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.5.6.2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sampieri K, Fodde R. Cancer stem cells and metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol 2012; 22:187-93; PMID:22774232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baxter J, Sauer S, Peters A, John R, Williams R, Caparros ML, Arney K, Otte A, Jenuwein T, Merkenschlager M, et al. Histone hypomethylation is an indicator of epigenetic plasticity in quiescent lymphocytes. EMBO J 2004; 23:4462-72; PMID:15510223; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ritou E, Bai M, Georgatos SD. Variant-specific patterns and humoral regulation of HP1 proteins in human cells and tissues. J Cell Sci 2007; 120:3425-35; PMID:17855381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.012955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Miyagi S, Koide S, Saraya A, Wendt GR, Oshima M, Konuma T, Yamazaki S, Mochizuki-Kashio M, Nakajima-Takagi Y, Wang C, et al. The TIF1beta-HP1 System Maintains Transcriptional Integrity of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep 2014; 2:145-52; PMID:24527388; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med 1997; 3:730-7; PMID:9212098; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm0797-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:3983-8; PMID:12629218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0530291100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 2004; 432:396-401; PMID:15549107; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature 2007; 445:106-10; PMID:17122772; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, Bruns CJ, Heeschen C. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2007; 1:313-23; PMID:18371365; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Pang R, Law WL, Chu AC, Poon JT, Lam CS, Chow AK, Ng L, Cheung LW, Lan XR, Lan HY, et al. A subpopulation of CD26+ cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity in human colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 6:603-15; PMID:20569697; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Dieter SM, Ball CR, Hoffmann CM, Nowrouzi A, Herbst F, Zavidij O, Abel U, Arens A, Weichert W, Brand K, et al. Distinct types of tumor-initiating cells form human colon cancer tumors and metastases. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9:357-65; PMID:21982235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science 2010; 327:542-5; PMID:20110496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1180794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Roth S, Fodde R. Quiescent stem cells in intestinal homeostasis and cancer. Cell Commun Adhes 2011; 18:33-44; PMID:21913875; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/15419061.2011.615422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:1420-8; PMID:19487818; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI39104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lim J, Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: insights from development. Development 2012; 139:3471-86; PMID:22949611; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.071209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Millanes-Romero A, Herranz N, Perrera V, Iturbide A, Loubat-Casanovas J, Gil J, Jenuwein T, Garcia de Herreros A, Peiro S. Regulation of heterochromatin transcription by Snail1/LOXL2 during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell 2013; 52:746-57; PMID:24239292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Maison C, Romeo K, Bailly D, Dubarry M, Quivy JP, Almouzni G. The SUMO protease SENP7 is a critical component to ensure HP1 enrichment at pericentric heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012; 19:458-60; PMID:22388734; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Leroy G, Chepelev I, Dimaggio PA, Blanco MA, Zee BM, Zhao K, Garcia BA. Proteogenomic characterization and mapping of nucleosomes decoded by Brd and HP1 proteins. Genome Biol 2012; 13:R68; PMID:22897906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. David CJ, Manley JL. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulation in cancer: pathways and programs unhinged. Genes Dev 2010; 24:2343-64; PMID:21041405; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1973010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Biamonti G, Bonomi S, Gallo S, Ghigna C. Making alternative splicing decisions during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Cell Mol Life Sci 2012; 69:2515-26; PMID:22349259; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-012-0931-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Warzecha CC, Carstens RP. Complex changes in alternative pre-mRNA splicing play a central role in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Semin Cancer Biol 2012; 22:417-27; PMID:22548723; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bol 2014; 15:178-96; PMID:24556840; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Revi Mol Cell Biol 2003; 4:33-45; PMID:12511867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Orian-Rousseau V. CD44, a therapeutic target for metastasising tumours. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46:1271-7; PMID:20303742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Brown RL, Reinke LM, Damerow MS, Perez D, Chodosh LA, Yang J, Cheng C. CD44 splice isoform switching in human and mouse epithelium is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:1064-74; PMID:21393860; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI44540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Norwood LE, Grade SK, Cryderman DE, Hines KA, Furiasse N, Toro R, Li Y, Dhasarathy A, Kladde MP, Hendrix MJ, et al. Conserved properties of HP1(Hsalpha). Gene 2004; 336:37-46; PMID:15225874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Lieberthal JG, Kaminsky M, Parkhurst CN, Tanese N. The role of YY1 in reduced HP1alpha gene expression in invasive human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res 2009; 11:R42; PMID:19566924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Weinmann AS, Yan PS, Oberley MJ, Huang TH, Farnham PJ. Isolating human transcription factor targets by coupling chromatin immunoprecipitation and CpG island microarray analysis. Genes Deve 2002; 16:235-44; PMID:11799066; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.943102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Oberley MJ, Inman DR, Farnham PJ. E2F6 negatively regulates BRCA1 in human cancer cells without methylation of histone H3 on lysine 9. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:42466-76; PMID:12909625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M307733200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Adachi N, Lieber MR. Bidirectional gene organization: A common architectural feature of the human genome. Cell 2002; 109:807-9; PMID:12110178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00758-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Trinklein ND, Aldred SF, Hartman SJ, Schroeder DI, Otillar RP, Myers RM. An abundance of bidirectional promoters in the human genome. Genome Res 2004; 14:62-6; PMID:14707170; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.1982804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]