Abstract

Anthocyanins are induced in plants in response to abiotic stresses such as drought, high salinity, excess light, and cold, where they often correlate with enhanced stress tolerance. Numerous roles have been proposed for anthocyanins induced during abiotic stresses including functioning as ROS scavengers, photoprotectants, and stress signals. We have recently found different profiles of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants exposed to different abiotic stresses, suggesting that not all anthocyanins have the same function. Here, we discuss these findings in the context of other studies and show that anthocyanins induced in Arabidopsis in response to various abiotic stresses have different localizations at the organ and tissue levels. These studies provide a basis to clarify the role of particular anthocyanin species during abiotic stress.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, abiotic stress, anthocyanin, localization

Abbreviations

- A5

cyanidin 3-O-[2-xylosyl-6-O-(4(glucosyl)-p-coumaroyl)]5-[6-O-(malonyl)glucoside]

- A11

cyanidin 3-O-[2-(2-(sinapoyl)xylosyl)-6-O-(4(glucosyl)-p-coumaroyl)glucoside]5-[6-O-(malonyl)glucoside]

- AIC

anthocyanin induction condition

- C3G

cyanidin 3-O-glucoside

- Col

Columbia-0

- HPLC-PDA

extinction coefficient, ε high performance liquid chromatography- photodiode array detection

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Anthocyanins are plant pigments of the flavonoid subclass of phenylpropanoids characterized by a 3,5,7-trihydroxylated flavylium backbone.1 The red-to-purple color imparted by anthocyanins to flowers, fruits, and seeds act as visual deterrents to herbivores, and attractants to pollinators and seed dispersers. Anthocyanins and other flavonoids also contribute to stress tolerance in plants. There is a growing interest in understanding the mechanisms by which anthocyanins help plants cope with abiotic stress, most importantly in the context of crop yield reduction due to global climate change. Anthocyanins are commonly induced in plant vegetative tissues in response to a number of different abiotic stresses including drought, salinity, excess light, sub- or supra-optimal temperatures, and nitrogen and phosphorous deficiency.2-8 The proposed roles of anthocyanins during abiotic stresses include quenching of ROS,9,10 photoprotection,11,12 stress signaling,13,14 and xenohormesis (i.e., the biological principle that relates bioactive compounds in environmentally stressed plants and the increase in stress resistance and survival in animals that feed from them).15,16

Plants as a group produce hundreds of structurally distinct anthocyanin species. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) alone produces more than 20 different types of anthocyanins, but whether they have specific functions is unknown. Whereas all anthocyanins could have identical roles, the high metabolic cost of adding numerous decorations (e.g. sugar and acyl groups) to the flavylium backbone in the different anthocyanin species makes this scenario very unlikely.

We recently reported that distinct profiles of anthocyanins are induced in seedlings of Arabidopsis in response to different abiotic stresses.4 We analyzed seedlings grown in 8 abiotic stress conditions, including high salinity, cold, and an artificial stress medium termed anthocyanin induction condition (AIC), which consists of 3% sucrose and no additional nutrients. The fact that distinct profiles of anthocyanins are induced by different abiotic stresses suggested that different anthocyanins, or profiles of anthocyanins, have different functions in planta. Another recent study demonstrated that only a subset of Arabidopsis anthocyanins (A11, A9, A8 and A5) were induced in response to short-term drought stress.17 The anthocyanin profile induced by drought17 was most similar to that induced in response to salt (MgSO4) stress in our experiments.4 Therefore, it is possible that plants exposed to drought and salt stresses take advantage of the same anthocyanin, or set of anthocyanins, whereas plants subjected to other abiotic stress conditions may benefit from different anthocyanin species.

A11 was the major anthocyanin induced in Arabidopsis in response to salt (MgSO4)4 and drought17 stresses. The synthesis of A11 is metabolically more costly than C3G, an anthocyanin that has widespread occurrence in plant species, as A11 has 6 additional sugar and acyl decorations, and has 3 times the mass of C3G. A recent study demonstrated that acylated (coumaroylated) anthocyanins in the epidermal cells of sweet basil conferred tolerance to excess light.12 A11 is a coumaroylated anthocyanin and absorbs 1.8 times more visible light (at 530 nm) and almost 3 times more UV-B (at 300 nm) than C3G at equivalent concentrations (Table 1). In addition, A11 also contains a sinapoyl group, which has been recently shown to confer major increases in the antioxidant capacity of anthocyanins.18 This raises the question of whether A11 serves as a photoprotectant, as an antioxidant, both, or perhaps neither in vivo. Constitutive anthocyanin accumulation in plants overexpressing the anthocyanin regulatory gene PAP1, conferred enhanced tolerance to drought and oxidative stresses.10 A11 is by far the predominant anthocyanin induced by PAP1 in leaves, but not in petioles, hypocotyls or roots.10 Whereas these studies cannot rule out that another compound induced by PAP1 enhanced tolerance to the oxidative stresses, the predominant induction of A11 specifically in leaves during oxidative stresses suggest that A11 has a major function in quenching excess ROS generated by photosynthesis.

Table 1.

Light absorbance comparisons between anthocyanins A11 and C3G

| Wavelength (nm) | 530 | 300 |

| A11 ε (L cm−1 mol) | 61,300 | 61,300 |

| C3G ε (L cm−1 mol) | 34,700 | 17,300 |

| A11/C3G | 1.8 | 3.5 |

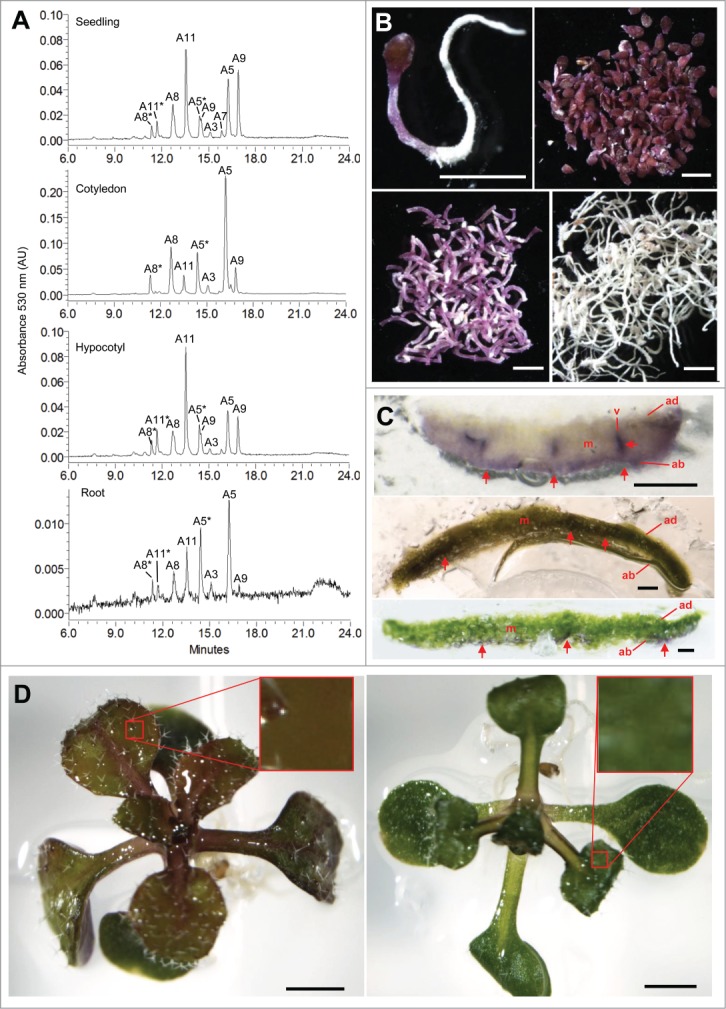

To determine whether A11 is always the major anthocyanin in Arabidopsis leaves, we measured A11 levels in the cotyledons of seedlings grown in AIC, a stress condition where visible chlorophyll does not develop, and thus anthocyanin would not be required to protect highly photosynthetically active machinery from excess ROS. Our results show that A11 was not a major anthocyanin in the cotyledons in AIC, despite the fact that A11 is among the most abundant anthocyanins in the whole seedling extract (Fig. 1A). We visually confirmed that there was no cross-contamination among dissected seedling organs by microscopy (Fig. 1B). We found the majority of A11 induced in AIC was in the hypocotyl (Fig. 1A, second from bottom). By analyzing cross sections of the hypocotyl, we detected anthocyanin accumulation in all cell layers (Fig. S1), suggesting that A11 has a unique function in this organ. By contrast, A5, with no sinapoyl group, was the predominant anthocyanin in cotyledons (Fig. 1A, second from top) and roots from seedlings in AIC (Fig. 1A, bottom), as well as in roots of seedlings overexpressing PAP1.17 These results show that both cotyledons with low photosynthetic activity and non-photosynthetic tissues under AIC favor the synthesis of A5 and not A11 as the major anthocyanin. In addition, A5 lacks the extra antioxidant capacity afforded by the sinapoyl group in A11, suggesting that A5 does not have a major role in protection against photosynthetically-derived ROS.

Figure 1.

Localization of anthocyanins in Arabidopsis during AIC and MgSO4 stresses. (A) HPLC-PDA chromatograms of aqua-methanol extracts from whole seedling (Top), cotyledon (second from top), hypocotyl (second from bottom), and root (bottom). Note scale of chromatograms differs. (B) Microscopic analysis of the seedling tissues analyzed in (A). Seedlings grown for 5 days in AIC were lyophilized for 3 days and imaged. Whole seedling prior to dissection (top left), dissected cotyledons (top right), hypocotyls (bottom left), and roots (bottom right). Scale bar 1mm. (C) Detection of anthocyanin pigmentation in cotyledons of seedlings grown in AIC (top), or on 1/2MS 1% sucrose agar medium containing 100 mM MgSO4 under 150 µmol m2 s−1 light (middle) or 40 µmol m2 s−1 light (bottom). Mesophyl, m; abaxial epidermis, ab; adaxial epidermis ad; vasculature, v. Scale bar 200 µm. (D) Leaf color of seedling leaf grown for 10 days on 1/2MS 1% sucrose agar medium containing 100 mM MgSO4 under 150 µmol m2 s−1 light (left) or 40 µmol m2 s−1 light (right). Note: anthocyanins developed a brown color indicative of oxidation under 150 µmol m2 s−1 light. Scale bar 1 mm.

Under excess salinity conditions, chloroplast generates ROS (reviewed by19) and plants accumulate predominantly A11.4 To determine whether the localization of anthocyanins in leaves differ between oxidative or non-oxidative stress growth conditions, we analyzed seedlings grown in high salt and high light (100 mM MgSO4, 150 µmol m2 s−1) and AIC, respectively. In cotyledons grown in AIC, anthocyanins accumulated mainly in the abaxial epidermis and vasculature, but not in mesophyll cells (Fig. 1C, top). By contrast, anthocyanins localized primarily to the mesophyll cells of seedlings grown in high salt and high light conditions (Fig. 1C, middle). To determine whether the induction of anthocyanins in mesophyll cells correlated with high light that potentially generated excess ROS, we repeated the experiment under low light (40 µmol m2 s−1). We found that anthocyanins were not present in the mesophyll cells under low light conditions (Fig. 1C, bottom). Interestingly, the anthocyanins induced in response to high salt had a brown coloration, (compared to purple color of anthocyanins in AIC; Fig. 1B–C), indicative of anthocyanin oxidation only in seedlings grown under high light (Fig. 1D, left), supporting their potential roles as antioxidants.

These results, in combination with our recent finding that A11 was the predominant anthocyanin induced in response to MgSO4 stress,4 suggest that A11 functions as an antioxidant to protect photosynthetic mesophyll cells from oxidative damage caused by the generation of excess ROS. It is possible that A11 in the hypocotyl of seedlings grown under AIC functions as an 'insulator' to prevent ROS signals from traveling between the root and the cotyledon. In addition, A5 in roots and other non-photosynthetic tissues may not act as an antioxidant, and warrants further investigation.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Wild-type seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana (Col) were surface-sterilized, stratified, and grown as indicated in.4

Chemical analysis

Anthocyanins were extracted from equal dry weights of tissue and analyzed by HPLC-PDA as indicated in.4

Anthocyanin distribution

Fresh leaf tissues were imbedded in Paraplast X-tra tissue medium (Fisher) and hand-sectioned prior to imaging with an SMZ1500 stereomicroscope equipped with a Digital Sight DS-Fi1 camera (Nikon).

Funding

We thank the Pelotonia Postdoctoral Fellowship Program for supporting NK and the NIH Postbacculaureate Research Education Program (PREP) Grant R25 GM089571 for supporting GK. This project was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB-1048847 to EG and MSO.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Grotewold E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2006; 57:761-80; PMID:16669781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie PJ, Alfenito MR, Walbot V. Impact of low-temperature stress on general phenylpropanoid and anthocyanin pathways: enhancement of transcript abundance and anthocyanin pigmentation in maize seedlings. Planta 1994; 194:541-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00714468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garriga M, Retamales JB, Romero-Bravo S, Caligari PD, Lobos GA. Chlorophyll, anthocyanin, and gas exchange changes assessed by spectroradiometry in Fragaria chiloensis under salt stress. J Int Plant Biol 2014; 56:505-15; PMID:24618024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/jipb.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovinich N, Kayanja G, Chanoca A, Riedl K, Otegui MS, Grotewold E. Not all anthocyanins are born equal: distinct patterns induced by stress in Arabidopsis. Planta 2014; 240:931-40; PMID:24903357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00425-014-2079-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miki S, Wada KC, Takeno K. A possible role of an anthocyanin filter in low-intensity light stress-induced flowering in Perilla frutescens var. crispa. J Plant Physiol 2014; 175C:157-62; PMID:25544591; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng M, Hudson D, Schofield A, Tsao R, Yang R, Gu H, Bi YM, Rothstein SJ. Adaptation of Arabidopsis to nitrogen limitation involves induction of anthocyanin synthesis which is controlled by the NLA gene. J Exp Bot 2008; 59:2933-44; PMID:18552353; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/ern148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Zheng S, Liu Z, Wang L, Bi Y. Both HY5 and HYH are necessary regulators for low temperature-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis seedlings. J Plant Physiol 2011; 168:367-74; PMID:20932601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen KM, Lea US, Slimestad R, Verheul M, Lillo C. Differential expression of four Arabidopsis PAL genes; PAL1 and PAL2 have functional specialization in abiotic environmental-triggered flavonoid synthesis. J Plant Physiol 2008; 165:1491-9; PMID:18242769; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould K, McKelvie J, Markham K. Do anthocyanins function as antioxidants in leaves? Imaging of H2O2 in red and green leaves after mechanical injury. Plant Cell Environ 2002; 25:1261-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00905.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakabayashi R, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Urano K, Suzuki M, Yamada Y, Nishizawa T, Matsuda F, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Shinozaki K, et al.. Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J 2014; 77:367-79; PMID:24274116; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/tpj.12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes NM, Carpenter KL, Keidel TS, Miller CN, Waters MN, Smith WK. Photosynthetic costs and benefits of abaxial versus adaxial anthocyanins in Colocasia esculenta 'Mojito'. Planta 2014; 240:971-81; PMID:24903360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00425-014-2090-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tattini M, Landi M, Brunetti C, Giordano C, Remorini D, Gould KS, Guidi L. Epidermal coumaroyl anthocyanins protect sweet basil against excess light stress: multiple consequences of light attenuation. Physiol Plant 2014; 152:585-98; PMID:24684471; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/ppl.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pourcel L, Irani NG, Koo AJ, Bohorquez-Restrepo A, Howe GA, Grotewold E. A chemical complementation approach reveals genes and interactions of flavonoids with other pathways. Plant J 2013; 74:383-97; PMID:23360095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/tpj.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marko D, Puppel N, Tjaden Z, Jakobs S, Pahlke G. The substitution pattern of anthocyanidins affects different cellular signaling cascades regulating cell proliferation. Mol Nutr Food Res 2004; 48:318-25; PMID:15497183; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mnfr.200400034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howitz KT, Sinclair DA. Xenohormesis: sensing the chemical cues of other species. Cell 2008; 133:387-91; PMID:18455976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pourcel L, Grotewold E. Phytochemicals, plant development and growth – Who is in control? Plant-Derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function and Application. In: Osbourn AE, Lanzotti V, eds. New York: Springer; 2009:269-79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakabayashi R, Mori T, Saito K. Alternation of flavonoid accumulation under drought stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav 2014; 9:e29518; PMID:25763629; 10.4161/psb.29518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matera R, Gabbanini S, Berretti S, Amorati R, De Nicola GR, Iori R, Valgimigli L. Acylated anthocyanins from sprouts of Raphanus sativus cv. Sango: isolation, structure elucidation and antioxidant activity. Food Chem 2015; 166:397-406; PMID:25053073; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen Species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot 2012; 2012:26; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2012/217037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.