Abstract

The major known function of cytokines that belong to type I interferons (IFN, including IFNα and IFNβ) is to mount the defense against viruses. This function also protects the genetic information of host cells from alterations in the genome elicited by some of these viruses. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrated that IFN also restrict proliferation of damaged cells by inducing cell senescence. Here we investigated the subsequent role of IFN in elimination of the senescent cells. Our studies demonstrate that endogenous IFN produced by already senescent cells contribute to increased expression of the natural killer (NK) receptor ligands, including MIC-A and ULBP2. Furthermore, neutralization of endogenous IFN or genetic ablation of its receptor chain IFNAR1 compromises the recognition of senescent cells and their clearance in vitro and in vivo. We discuss the role of IFN in protecting the multi-cellular host from accumulation of damaged senescent cells and potential significance of this mechanism in human cancers.

Keywords: interferon, NK cells, senescence, senescent cell clearance

Abbreviations

- DDR

DNA damage response

- HGPS

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome

- IFN

type I interferons

- IFNAR1

type I IFN receptor

- NK

natural killer cells

- SA-βGal

senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- WS

Werner syndrome

Introduction

High fidelity of genetic traits inheritance depends on the multitude of mechanisms that evolved to protect genomic integrity and decrease the frequency of cancer development.1,2 Among these mechanisms is restriction of propagation of viruses that can integrate into genome and alter the genetic programs of host cells.3 Cytokines that belong to the family of type I interferons (IFN, including IFNα and IFNβ) play a major role in anti-viral defenses (reviewed in).4 Furthermore, IFN were recently implicated in restricting the propagation of the long interspersed repetitive genetic elements.5 Thus, IFN can contribute to the protection of genome via prevention of the alteration of genomic DNA by viruses or genetic elements.

Furthermore, our recent studies suggested an additional role of IFN in protecting the multicellular host genome from accumulating already damaged cells. Endogenous IFN produced in cells that harbor DNA damage and exhibit the DNA damage response (DDR) are actually responsible for driving the program of cell senescence.6 These findings suggest that IFN can also contribute to the maintenance of genomic integrity by preventing proliferation of genetically altered cells.

Intriguingly, the presence of senescent cells in multi-cellular host carries substantial risks related to tissue aging but also to cancer development (reviewed in).7,8 Elimination of already senescent cells is therefore important for the maintenance of overall genomic integrity. Specific mechanisms have evolved to recognize these senescent cells and eliminate them from mammalian organisms using activity of macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells.

The latter require the expression of specific ligands (such as NKG2D ligands MICA/MICB, ULBP2 and others) that are recognized by NK cells and serve to mark these senescent cells for in vivo clearance.9-13 While the role of secreted factors (known as senescence-associated secretory phenotype) in communicating the need of damaged/senescent cell elimination to the immune system has been well described,7,14,15 the importance of IFN in this process is yet to be largely determined. Here we show that expression of NK ligands in already senescent cells depends on the action of IFN. Neutralization of IFN pathway attenuates the expression of these ligands and suppresses the clearance of senescent cells in vitro and in vivo. These data are indicative of the role of IFN in the elimination of senescent cells from the multi-cellular organisms.

Results

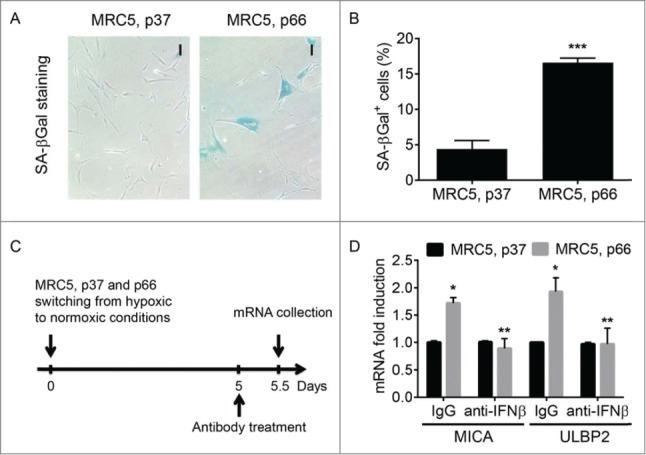

Mammalian experiments demonstrated that oncogene/DNA damage-dependent senescence is associated with expression of specific ligands (such as NKG2D ligands MICA/MICB, ULBP2 and others) that are recognized by NK cells and serve to mark these senescent cells for in vivo clearance.9-13 We sought to determine whether IFN play a role in the expression of the NK ligands in the senescent cells. Initially we used MRC-5 diploid human fibroblasts that can freely proliferate at early passage (for example, passage 37) but undergo the replicative senescence when serially cultured to a late passage and switched from hypoxic to normoxic growth conditions as evident from staining for the senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βGal) activity (Fig. 1A–B). After achieving the senescent state in the late passage cultures, we have incubated these cells with control antibody or antibody against human IFNβ (time line depicted in Fig. 1C). Statistically significant higher levels of MIC-A and ULBP2 mRNA were detected in the late passage MRC-5 cells compared to the early passage (Fig. 1D). These results together with findings of greater number of senescent cells in the late passage cultures (Fig. 1A–B) are consistent with previously reported increase in the NK ligands levels in the senescent cells.9-13

Figure 1.

The role of IFNβ in the expression of NKG2D ligands by senescent human fibroblasts. (A). Senescence-associated (SA)-βGal staining of normal human fibroblasts (MRC5) that either continued to proliferate (passage (p) 37) or underwent the replicative senescence (p66). Here and thereafter: data are shown as average± S.D.; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Magnification bar: 100 µm. (B). Quantitation of the number of SA-βGal positive cells in the culture of MRC5, p37 or p66. 9–11 fields randomly chosen from 3 independent experiments. (C). The scheme of the experiment to determine the role of IFNβ in the expression of NKG2D ligands by senescent human fibroblasts. (D). The effect of IFNβ neutralizing antibody on the expression of mRNA of NKG2D ligands MICA and ULBP2 respectively on early (p37) and late passages (p66) of MRC5 fibroblasts. Asterisk indicates p < 0.05 between MRC5 fibroblasts cultured for 66 passages over those cultured for 37 passages. Double asterisk indicates p < 0.01 between MRC5, p66 fibroblasts cultured in the presence of neutralizing antibody against human IFNβ over those cells with control antibody (IgG).

Intriguingly, treatment of the late passage cultures with the neutralizing antibody against human IFNβ decreased MIC-A and ULBP2 mRNA levels to the levels seen in the early passage cultures (Fig. 1D). Importantly, expression of these genes in the early passage MRC-5 cells was not affected by the anti-IFNβ antibody treatment. These data suggest that endogenous IFNβ produced by the senescent cells contributes to the induction of the NK ligand genes.

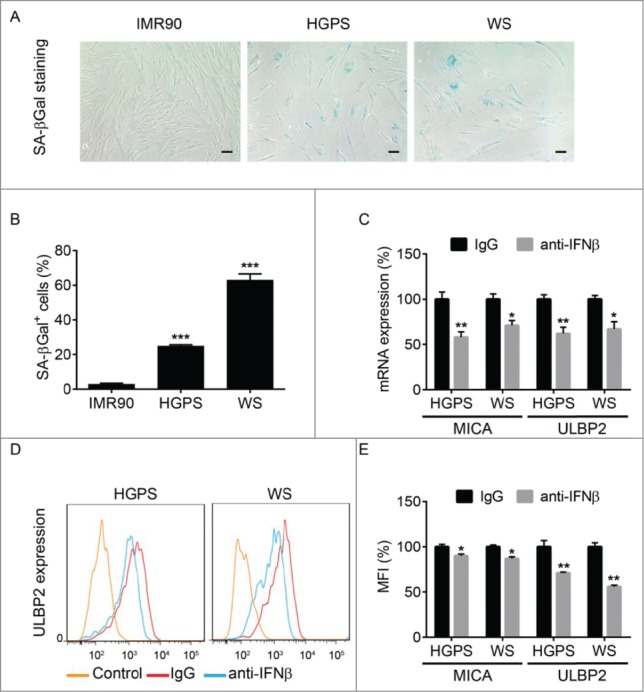

In order to further test this hypothesis we used human diploid fibroblasts from Werner syndrome or Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome patients known to exhibit persistent DNA damage and achieve senescence.16-18 We found that these cultures indeed contain a high number of senescent cells compared to normal diploid human IMR90 fibroblasts (Fig. 2A–B). Importantly, a short-term treatment of cultures of fibroblasts from either Werner syndrome or Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome patients with anti-IFNβ neutralizing antibody did not reduce the number of senescent cells (data not shown) yet significantly suppressed the expression of MIC-A and ULBP2 mRNA (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

The role of IFNβ in the expression of NKG2D ligands by fibroblasts from progeria patients. (A). SA-βGal staining of normal human fibroblasts (IMR90) or diploid fibroblasts from patients with Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) or Werner syndrome (WS). (B). Quantitation of the number of SA-βGal positive cells in culture of IMR90, HGPS, and WS fibroblasts. 9–11 Fields were randomly chosen from 3 independent experiments. Asterisks: p < 0.001. (C). The effect of IFNβ neutralizing antibody on the expression of mRNA of MICA and ULBP2 on HGPS and WS human fibroblasts. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (D). FACS analysis of ULBP2 levels in either IgG- or anti-hIFNβ-treated WS and HGPS cells. Control reactions contained no primary antibody. (E). Quantification of FACS analysis of MICA/MICB and ULBP2 levels in both IgG- or anti-hIFNβ-treated HGPS and WS cells. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Additional flow cytometry analysis of these cultures further revealed a modest yet significant decrease in the cell surface levels of MIC-A/MIC-B and ULBP2 proteins in cells treated with anti-IFNβ antibody compared to those that received control immunoglobulins (Figs. 2D–E). Collectively these results indicate that endogenous IFN-β contributes to the regulation of expression of the NK ligand genes and presentation of their protein products on the surface of senescent cells.

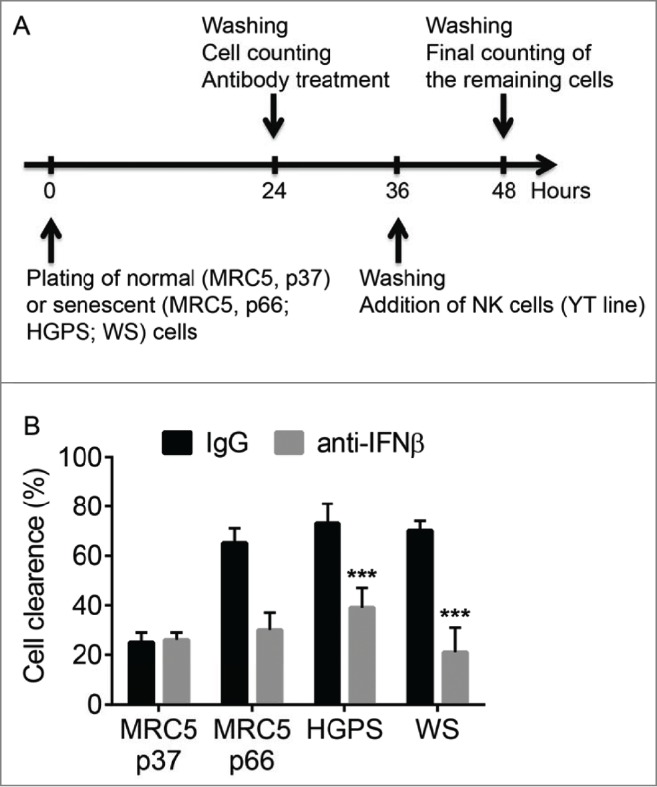

We next sought to determine the functional significance of this regulation using the senescent cells clearance assay in vitro.10,11 In this assay, we incubated cultures of MRC-5, Werner syndrome or Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome patient-derived diploid fibroblasts with the YT NK cell line. The design for these experiments is depicted in Figure 3A. After an overnight incubation, the YT cells were rinsed off and the percent of fibroblasts that disappeared from these cultures during this time was calculated. This approach was previously deemed superior to the radioactive Chromium release-based cell lysis assay because of expectedly high level of basic clearance of the non-self fibroblasts by the heterologous YT cell line.10,11

Figure 3.

The role of IFNβ in the clearance of senescent cells in vitro. (A). Scheme of the experiment to determine the role of IFNβ in the clearance of senescent cells in vitro. (B). Growing (MRC5, p37) or senescent cells (MRC5, p66; HGPS or WS cells) were pre-treated with IFNβ neutralizing antibody (or control IgG) for 12 h, washed and incubated with natural killer YT cells overnight. Percentage of clearance of indicated cells is depicted. ***p < 0.001.

Indeed, we observed that approximately a quarter of all proliferating early passage MRC-5 cells was eliminated by the YT NK cells (Fig. 3B). Pretreatment of these cultures with IFNβ-neutralizing antibody did not significantly affect this number indicating that overall activity of NK cells in vitro was not dependent on the presence of IFNβ. Importantly, the percent of cleared cells was greatly increased in fibroblast cultures containing high number of senescent cells including those of late passage MRC-5 and fibroblasts from Werner syndrome or Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome patients (Fig. 3B). These results are in line with previously reported preferential clearance of senescent cells by NK.10,11 Remarkably, the efficacy of clearance of senescent fibroblast cells by YT cells was dramatically reduced by pre-treating the fibroblast cultures with anti-IFNβ neutralizing antibody (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that endogenous IFNβ produced by senescent cells contributes to their efficient killing by NK cells.

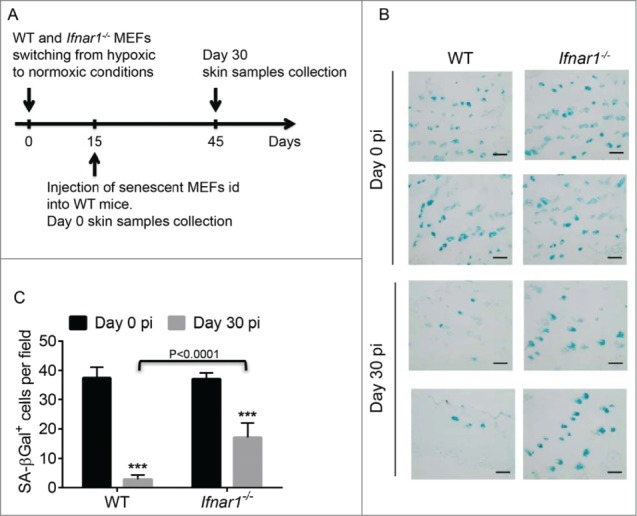

We next determined whether sensitivity of senescent cells to secreted IFN may regulate their persistence in vivo. To this end, we have prepared cultures of already senescent mouse embryo fibroblasts derived from wild type animals (Ifnar1+/+) or animals lacking the IFNAR1 chain of type I IFN receptor (Ifnar1−/−) by serially passaging these cells in vitro. We then injected the same number of Ifnar1+/+ or Ifnar1−/− SA-β-Gal positive fibroblasts into the skin of wild type syngeneic (C57Bl6) mice (Fig. 4A). Analysis of the injection sites for the SA-βGal-positive cells carried out 30 days post injection revealed that a substantial fraction of senescent cells was eliminated by the host animal. Importantly, a significantly greater number of senescent Ifnar1−/− MEFs (than wild type senescent MEFs) remained in the host skin at that time (Fig. 4B–C). This result indicates that IFN signaling within senescent cells is important for their efficient clearance in vivo.

Figure 4.

Role of IFNβ in the clearance of senescent cells in vivo. (A). Scheme of the experiment to determine the role of IFNβ in the clearance of senescent cells after intradermal injection (id). (B). SA-βGal staining of wild-type (WT) mice skin sections at the indicated days post intradermal injection (pi) with primary MEFs from Ifnar1+/+ (WT) or Ifnar1−/− animals. Magnification bar: 100 µm. (C). Quantitation of the number of SA-βGal positive cells shown in F. 10 fields were randomly chosen from 3 independent experiments. Asterisks: p < 0.001.

Discussion

Previous reports from our and other groups have demonstrated that exogenously administered or endogenous IFNβ acts to stimulate cell senescence.6,19 While senescence of damaged cells protects a multi-cellular host from the tumorigenesis and transmission of altered genetic information, the accumulation of senescent damaged cells burdens the organism. This is why elimination of senescent cell by immune system (including NK cells) plays an important role in tissue and organism homeostasis.20-24 Importantly, our current data suggest that production of IFNβ by already senescent cells increases the expression of the NKG2D ligands that enable these cells to be recognized and cleared by NK cells in vitro and in vivo. These results demonstrate that the mechanisms of innate immunity that are designed to rid the multicellular organism of damaged/senescent cells12,13 that display specific recognition ligands on their surface function in an IFNβ-dependent manner.

Given a known role of type I IFN in maturation and function of NK and other cells of innate immunity,25 the importance of overall IFN signaling in elimination of damaged cells could be implied. Importantly, our results focused on effects of IFNβ on target cells also demonstrated that already senescent cells require IFNβ production for maximal expression of the NKG2D ligands (Figs. 1–2). These ligands were shown to enable the detection of senescent cells by NK cells for subsequent cytotoxic elimination.10,11,13 Accordingly, neutralization of IFNβ in vitro or knockdown of IFNAR1 in vivo in target senescent cells attenuated clearance of these cells (Figs. 3–4).

The mechanism by which IFN produced by senescent cells contribute to the clearance of these cells remains to be further elucidated. All effects of IFN on cells are mediated by a cognate receptor whose stability and levels are tightly regulated by ubiquitination and degradation of its IFNAR1 chain.26-31 Signaling downstream of IFN receptor that leads to the NK ligand gene expression may include conventional Janus kinase- and signal transducers and activators of transcription-dependent as well as independent pathways that lead to induction of IFN-stimulated genes.32

On one hand, current data suggest a model role of IFN in the expression of the NK ligand genes. These genes do not belong to the bona fide IFN-stimulated genes signature and, therefore, are likely to be activated indirectly. On the other hand, IFN were shown to stimulate activation of p53 tumor suppressor protein.6,19,33 Importantly, p53 activities were shown to trigger production of several chemokines that can further increase the recruitment of NK cells (and, potentially, other cytotoxic immune cells) to the senescent targets.34 Furthermore, besides NK, other immune cells (e.g. macrophages) can plausibly contribute to the IFN-stimulated elimination of senescent cells in mammalian organisms.

Recently published evidence collectively suggests a multi-functional role of IFNβ in guarding the genome stability. At a cellular level, IFNβ prevents genome alterations through limiting the retrotransposon activities.5 In addition, IFNβ acts at a multi-cellular organism level by restricting renewal and proliferation of genetically altered damaged cells6 and ensuring their subsequent elimination (this study). Given that inefficient elimination of senescent cells is linked with diverse aging-related phenotypes,35 the mechanisms underlying the IFNβ-induced action upon senescent cells merit further investigation.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines and culture conditions

IMR 90 (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (HyClone Laboratories). MRC5 cells were cultured in DMEM plus 15% FBS. Human diploid fibroblast (HDF) cells from patients with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS, cell line AG0989B) and Werner syndrome (WS, cell line AG05229B) were purchased from Coriell Institute for Medical Research. MRC5, HGPS and WS cells were cultured in a Billups-Rothenberg modular incubator chambers at 3% O2 until they were transferred to 20% O2 culture condition to induce senescence. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Ifnar1+/+ and Ifnar1−/− mice (C57Bl/6J background) were prepared from day 14.5 embryos and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as previously described.27 The human natural killer (NK) cell line YT was grown in Iscove's MDM plus 20% FBS. Senescent cells were detected by senescence-associated (SA)-βGal assay using the Cell Signaling kit (cat # 9860).

Quantitative PCR

Growing (MRC5, p37) or senescent cells (MRC5, p66; HGPS or WS cells) were treated with either 10 µg/ml anti-human IFNβ neutralizing antibody or with isotype control (eBioscience) for 12 hours. The cells were then harvested, homogenized in Trizol reagent, and total RNA was extracted with chloroform. Reverse transcription was carried out using Revertaid first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific) and the cDNA was used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect the expression of MICA and ULBP2. The primers were MICA (FW, 5′-TCTTCCTGCTTCTGGCTGGCAT - 3′, REV, 5′- CCTGACTGCACAGATCCATCCC - 3′), ULBP2 (FW, 5′- CAAGTGCAGGAGCACCACTCG - 3′, REV, 5′- CAGATGCCAGGGAGGATGAAGC - 3′), GAPDH (FW, 5′- TCCATGACAACTTTGGTATCGTGG - 3′, REV, 5′- AGAGCCCCGCGGCCATCACG - 3′). qPCR was carried out by using Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry approaches were carried out as previously described.36-38 These approaches were used for analysis of MICA/MICB and ULBP2 surface expression. Senescent HGPS or Werner cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human MICA/MICB antibody (BioLegend), or primary anti-human ULBP2 (Novus Biologicals Inc.) antibody followed by staining with anti-mouse AF488 conjugated antibodies. Cells were analyzed by LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), using appropriate laser and filter settings for chemical fluorophores. Results were quantified with FlowJo 7.6 software.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Growing (MRC5, p37) or senescent cells (MRC5, p66; HGPS or WS cells) were plated in 12-well plates at 25,000 cells per well. The cells were treated with either 10 µg/ml anti-human IFNβ neutralizing antibody or isotype control (eBioscience) for 12 hours. After gently washing the plate 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2.5 × 105 YT cells were added to target cells. The plates were incubated under normal conditions for 12 h and then washed 3 times with PBS. Using a grid, the same areas in each well was counted prior to and after adding the YT cells and the NK cell cytotoxicity was expressed as ((number of cells prior adding YT cells - number of cells after incubation with YT cells)/number of cells prior adding YT cells) × 100%.

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

Primary Ifnar1+/+ (wild type) and Ifnar1−/− MEFs (described in 27) were cultured at normoxic conditions for 15 d and the amount of SA-βGal positive cells was determined by the Staining Kit from Cell Signaling. The number of MEFs injected into each mouse was normalized based on the percentage of SA-βGal positive cells. 2 × 105 of wild type or Ifnar1−/− senescent MEFs in 100 µl of PBS was injected intradermally into the left or right flank, respectively, of the same wild type C57Bl/6J mouse in triplicates. The mice were euthanized by CO2 either 3 hours (day 0) or 30 d post injection. The entire shaved flank of the skin at the injection site was excised, rinsed one time in PBS, placed in O.C.T. media (TED PELLA, INC.), and frozen at −80°C. The next day, the block was sectioned for a total of 120 µm where 4 representative sections were analyzed (each individual section is 6 µm). All the sections were placed in the fixative solution for 10 min followed by overnight incubation in SA-βGal Staining Solution. Then the slides were washed with PBS, air dried, and observed under the microscope. For quantification of the SA-βGal positive cells the tissues were observed under 20× magnification. Only sections that contained at least one blue cell and contained a totally tissue filled field were selected. All fields that met the above criteria were included in the analysis.

Statistical analyses

Every shown quantified result is an average of at least 3 independent experiments carried out in either triplicate or quadruplicate and calculated as a mean ± SD.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We thank M Wasik for reagents, and the members of JA Diehl and C Koumenis Labs (at the University of Pennsylvania) for critical suggestions.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH/NCI grant CA092900 (to SY Fuchs) and PO1 CA165997 (to SY Fuchs, JA Diehl and C Koumenis).

References

- 1.Lindahl T, Wood RD. Quality control by DNA repair. Science 1999; 286:1897-905; PMID:10583946; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.286.5446.1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasty P, Campisi J, Hoeijmakers J, van Steeg H, Vijg J. Aging and genome maintenance: lessons from the mouse? Science 2003; 299:1355-9; PMID:12610296; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1079161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitzman MD, Lilley CE, Chaurushiya MS. Genomes in conflict: maintaining genome integrity during virus infection. Ann Rev Microbiol 2010; 64:61-81; PMID:20690823; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katze MG, He Y, Gale M Jr. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2:675-87; PMID:12209136; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Q, Carbone CJ, Katlinskaya YV, Zheng H, Zheng K, Luo M, Wang PJ, Greenberg RA, Fuchs SY. Type I interferon controls propagation of long interspersed element-1. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:10191-9; PMID:25716322; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M114.612374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Q, Katlinskaya YV, Carbone CJ, Zhao B, Katlinski KV, Zheng H, Guha M, Li N, Chen Q, Yang T, et al.. DNA-damage-induced type I interferon promotes senescence and inhibits stem cell function. Cell Rep 2015; 11:785-97; PMID:25921537; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014; 509:439-46; PMID:24848057; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 2005; 120:513-22; PMID:15734683; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raulet DH, Guerra N. Oncogenic stress sensed by the immune system: role of natural killer cell receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:568-80; PMID:19629084; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagiv A, Biran A, Yon M, Simon J, Lowe SW, Krizhanovsky V. Granule exocytosis mediates immune surveillance of senescent cells. Oncogene 2013; 32:1971-7; PMID:22751116; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2012.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, Yee H, Zender L, Lowe SW. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 2008; 134:657-67; PMID:18724938; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 2007; 445:656-60; PMID:17251933; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature 2005; 436:1186-90; PMID:15995699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz-Espin D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:482-96; PMID:24954210; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP, Athineos D, Kang TW, Lasitschka F, Andrulis M, et al.. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:978-90; PMID:23770676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee AB, Costello C. Aneuploidy analysis in fibroblasts of human premature aging syndromes by FISH during in vitro cellular aging. Mech Ageing Dev 1998; 103:209-22; PMID:9701772; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein S, Wojtyk RI, Harley CB, Pollard JW, Chamberlain JW, Stanners CP. Protein synthetic fidelity in aging human fibroblasts. Adv Exp Med Biol 1985; 190:495-508; PMID:4083161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harley CB, Pollard JW, Chamberlain JW, Stanners CP, Goldstein S. Protein synthetic errors do not increase during aging of cultured human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980; 77:1885-9; PMID:6246512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moiseeva O, Mallette FA, Mukhopadhyay UK, Moores A, Ferbeyre G. DNA damage signaling and p53-dependent senescence after prolonged beta-interferon stimulation. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17:1583-92; PMID:16436515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ovadya Y, Krizhanovsky V. Senescent cells: SASPected drivers of age-related pathologies. Biogerontology 2014; 15:627-42; PMID:25217383; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10522-014-9529-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton DG, Krizhanovsky V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell Mol Life Sci: CMLS 2014; 71:4373-86; PMID:25080110; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iannello A, Raulet DH. Immune surveillance of unhealthy cells by natural killer cells. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 2013; 78:249-57; PMID:24135717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/sqb.2013.78.020255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagiv A, Krizhanovsky V. Immunosurveillance of senescent cells: the bright side of the senescence program. Biogerontology 2013; 14:617-28; PMID:24114507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10522-013-9473-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazeldine J, Lord JM. The impact of ageing on natural killer cell function and potential consequences for health in older adults. Ageing Res Rev 2013; 12:1069-78; PMID:23660515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arr.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Page C, Genin P, Baines MG, Hiscott J. Interferon activation and innate immunity. Rev Immunogenet 2000; 2:374-86; PMID:11256746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuchs SY. Hope and fear for interferon: the receptor-centric outlook on the future of interferon therapy. J Interferon Cytokine Res: Off J Int Soc Interferon Cytokine Res 2013; 33:211-25; PMID:23570388; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/jir.2012.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carbone CJ, Zheng H, Bhattacharya S, Lewis JR, Reiter AM, Henthorn P, Zhang ZY, Baker DP, Ukkiramapandian R, Bence KK, et al.. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B is a key regulator of IFNAR1 endocytosis and a target for antiviral therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:19226-31; PMID:23129613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1211491109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharya S, HuangFu WC, Dong G, Qian J, Baker DP, Karar J, Koumenis C, Diehl JA, Fuchs SY. Anti-tumorigenic effects of Type 1 interferon are subdued by integrated stress responses. Oncogene 2013; 32:4214-21; PMID:23045272; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2012.439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhattacharya S, Qian J, Tzimas C, Baker DP, Koumenis C, Diehl JA, Fuchs SY. Role of p38 protein kinase in the ligand-independent ubiquitination and down-regulation of the IFNAR1 chain of type I interferon receptor. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:22069-76; PMID:21540188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.238766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattacharya S, HuangFu WC, Liu J, Veeranki S, Baker DP, Koumenis C, Diehl JA, Fuchs SY. Inducible priming phosphorylation promotes ligand-independent degradation of the IFNAR1 chain of type I interferon receptor. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:2318-25; PMID:19948722; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.071498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Carvalho LP, Bhattacharya S, Carbone CJ, Kumar KG, Leu NA, Yau PM, Donald RG, Weiss MJ, Baker DP, et al.. Mammalian casein kinase 1alpha and its leishmanial ortholog regulate stability of IFNAR1 and type I interferon signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:6401-12; PMID:19805514; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.00478-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5:375-86; PMID:15864272; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takaoka A, Hayakawa S, Yanai H, Stoiber D, Negishi H, Kikuchi H, Sasaki S, Imai K, Shibue T, Honda K, et al.. Integration of interferon-alpha/beta signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence. Nature 2003; 424:516-23; PMID:12872134; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature01850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iannello A, Thompson TW, Ardolino M, Lowe SW, Raulet DH. p53-dependent chemokine production by senescent tumor cells supports NKG2D-dependent tumor elimination by natural killer cells. J Exp Med 2013; 210:2057-69; PMID:24043758; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20130783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011; 479:232-6; PMID:22048312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huangfu WC, Qian J, Liu C, Liu J, Lokshin AE, Baker DP, Rui H, Fuchs SY. Inflammatory signaling compromises cell responses to interferon alpha. Oncogene 2012; 31:161-72; PMID:21666722; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2011.221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng H, Qian J, Carbone CJ, Leu NA, Baker DP, Fuchs SY. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced elimination of the type 1 interferon receptor is required for efficient angiogenesis. Blood 2011; 118:4003-6; PMID:21832278; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng H, Qian J, Varghese B, Baker DP, Fuchs S. Ligand-stimulated downregulation of the alpha interferon receptor: role of protein kinase D2. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31:710-20; PMID:21173164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01154-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]