Abstract

Hypoxia is associated with poor response to treatment in various cancers. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a major transcription factor that mediates adaptation of cancer cells to a hypoxic environment and regulates many genes that are involved in key cellular functions, including cell immortalization, stem cell maintenance, autocrine growth/survival, angiogenesis, invasion/metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy. HIF-1α has been considered as an attractive therapeutic target for cancer treatment, but there is limited success in this research field. In the present study, we designed a recombinant lentivirus containing HIF-1α siRNA, developed stably transfected cell lines, and tested the anticancer effects of the siRNA on cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Our results indicated that the stable downregulation of HIF-1α reversed chemoresistance, inhibited proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells, and slowed down the tumor growth in breast cancer xenograft models. In conclusion, the recombinant lentivirus containing HIF-1α siRNA provides a new avenue for developing novel therapy for triple negative breast cancer.

Keywords: apoptosis, gene therapy, HIF-1α, recombinant lentivirus, siRNA therapy, stably transfected cell lines, triple negative breast cancer

Abbreviations

- BCSCs

breast cancer stem cells; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α; MDR, multidrug resistance; PARP, poly ADP ribose polymerase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common invasive cancers in women and is responsible for at least 13.7% of cancer-related deaths in women.1,2 Although recent advances in detection and treatment of breast cancer have been made, overall survival rate of patients with advanced breast cancer remains low.3,4 Currently available treatments for late-stage breast cancer rarely result in long-term benefits. Breast cancer is particularly difficult to treat when it metastasizes and/or becomes resistant to anti-estrogen therapies.5 In particular, patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) have the poorest prognosis, with the 5-year survival rate being lower than 30%.6,7 Therefore, there is an urgent need for developing novel approaches to overcoming the limitations of current breast cancer therapies.

Hypoxia is a characteristic feature of most solid tumors and related to poor response to treatment. In response to hypoxia, cancer cells undergo a variety of adoptive changes, including activation of signaling involve in cancer cells survival, proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, chemoresistance, and angiogenesis.8,9 HIF-1 is one of the major transcription factors that mediate this adaptive process of cancer cells to the hypoxic environment. HIF-1 is a heterodimer composed of the rate limiting factor HIF1α and the constitutively expressed HIF-1β;10 the latter is also called the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator and heterodimerises with several other factors, such as the Ahr transcription factor.11 HIF-1 controls the expression of almost 70 genes involved in cell proliferation, senescence, apoptosis, differentiation, angiogenesis, glucose metabolism and other cellular functions.12 For instance, VEGF is a typical downstream gene of HIF-1. It binds to its receptor VEGFR2 and is a major regulator of angiogenesis, which induces migration and proliferation of vascular vessel endothelial cells, promoting the increase in vasopermeability and angiogenesis and ameliorates wound blood supply.13 HIF-1α is induced by hypoxia, and also by oncogenes, such as HER-2/neu, v-src, and ras.14 In addition to oxygen-independent mechanisms, the PI3K, AKT and MAPK pathways mediate primarily non-hypoxic HIF regulation under normoxic environment. Consequently, HIFs and other pathways (PI3K/AKT and mTOR/p70S6K1) that lead to normoxic HIF activation are considered potential therapeutic targets.15 Despite mounting evidence implicates HIF-1α plays a major role in carcinogenesis and cancer development and progression, it has been regarded as “undruggable.” 16,17

A number of gene-therapy approaches have been developed for various cancers.18-20 HIF-1α is viewed as a viable prospective target for novel pharmacologic approaches to the clinical management of solid tumors as it is the major regulator of the hypoxic adaptive response.21,22 Multiple cellular pathways resulting in HIF activation could be successfully inhibited by use of different drugs (e.g., topotecan and inhibitors of heat shock protein 90 and mTOR).23 In the present study, we designed a recombinant lentivirus containing HIF-1α siRNA and obtained stably lentivirus-transfected cell lines and then tested its therapeutic effects on cancer cells under normoxic conditions. We found that downregulation of HIF-1α reversed chemoresistance and inhibited capability of proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells in vitro. Furthermore, the recombinant lentivirus significantly inhibited the growth of breast cancer xenografts in nude mice. The results suggest that the recombinant lentivirus targeting HIF-1α could be a new approach to breast cancer treatment.

Results

HIF-1α is stably knockdown via lentivirus carrying a HIF-1α shRNA

We observed the expression of GFP which was contained in lentivirus under an inverted fluorescence microscope. There were no significant changes in cell morphology between different groups (Fig. 1A). We then demonstrated that the expression of HIF-1α decreased dramatically at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1B). The inhibition rate reached 95% at protein level (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

The morphology and proliferation of cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA or NC shRNA cells and untreated MDA-MB-231 in vitro. (A) Flurescence produced by GFP can be seen in HIF-1α shRNA and NC shRNA cells (×200). (B) The decreased expression of HIF-1α in HIF-1α shRNA cells. (C) The relative expression of HIF-1α at protein level is inhibited by 95% in HIF-1α shRNA cells in comparison with NC shRNA cells. (D) Cell proliferation assay by the CCK8 showed inhibited cell growth in HIF-1α shRNA cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Downregulation of HIF-1α in MDA-MB-231 inhibits cell growth, migration and invasion capacity in vitro

We next investigated the effects of downregulated HIF-1α expression by lentivirus on the cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells. As shown in Figure 1D, inhibition of proliferation was observed in cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA. We next compared migratory ability and invasive potential among the cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA or NC shRNA and untreated MDA-MB-231. The number of cells crossing through the Transwell with Matrigel was significantly reduced in the HIF-1α shRNA-treated group (Fig. 2A). The number of cells crossing through in NC shRNA treated and untreated MDA-MB-231 cells was 1.63-fold and 1.76-fold higher than that of the cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA, respectively (Fig. 2B). In addition, compared with the NC shRNA treated cells, the HIF-1α shRNA treated cells showed 1.77- and 1.75-fold decreases in the number of cells migrating across the wound at 24 and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 2C) and the same figures were, 2.05- and 1.84-fold decreases, compared with that of MDA-MB-231, respectively (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

HIF-1α shRNA treated cells line showed decreases in migratory and invasive capacity in vitro. (A) Cell invision capacity of HIF-1α shRNA, NC shRNA cells and MDA-MB-231 was determined by transwell assay at 48 h (×200). (B) Quantitative analysis of the cells migration through the transwell chambers. **P<0.01. (C) Wound healing assays were performed at 24 and 48 h in HIF-1α shRNA, NC shRNA cells and MDA-MB-231 (×40). (D) Quantitative analysis of the healing rate of HIF-1α shRNA, NC shRNA cells and MDA-MB-231. **P<0.01.

Downregulation of HIF-1α promotes apoptosis and induces cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase

Both early and late apoptotic cell counts were increased in HIF-1α shRNA treated cells; the percentages of apoptotic cells were 5.87 ± 0.91% in untreated MDA-MB-231 cells, 6.5 ± 1.23% in NC shRNA treated cells, and 10.93 ± 1.12% in HIF-1α shRNA treated cells, respectively (Fig. 3). The number of cells in G2/M phase in HIF-1α shRNA cells were significantly increased, compared with the NC shRNA-treated cells (p = 0.002) and untreated MDA-MB-231 (p < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

HIF-1α shRNA treatement causes apoptosis in MDA-MB-231. Both early and late apoptosis were increased in HIF-1α shRNA cells examined by flow cytometry (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Stable downregulation of HIF-1α reduces the number of cells in G1 phase and increases the cell number in G2/M phase. The number of cells in G1/G0 phase in HIF-1α shRNA group is reduced compared with NC shRNA group and MDA-MB-231 group. Moreover, the number of cells in G2/M phase in HIF-1α shRNA group was increased compared with NC shRNA group and MDA-MB-231 (P < 0.05).

Knockdown of HIF-1α enhances the chemosensitivity of cells to THP and decreases the tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice

As shown in Table 2, the IC50 values for THP were 0.0707 ± 0.008, 0.094 ± 0.001 and 0.0986 ± 0.009 μg/mL in cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA, cells treated with NC shRNA, and untreated MDA-MB-231, respectively. The chemosensitivity of cells to THP was enhanced in HIF-1α shRNA treated cells compared to NC shRNA treated cells (p = 0.006) and untreated MDA-MB-231 (p = 0.003 Fig. 4). To further investigate the effects of HIF-1α-KD on MDA-MB-231 in vivo, we implanted HIF-1α shRNA and NC shRNA- transfected cells to each armpit fat pads subcutaneously in 6-week old NOD/SCID mice, respectively. Four weeks after the cell injections, tumor formation rates were shown decreased in mice injected with HIF-1α shRNA treated cells (Table 3). H & E staining and immunohistochemical assays were performed with the xenografts tissues. More necrotic tissue was shown in NC shRNA xenografts by H & E staining for more rapidly proliferation. ER, PR and Her2 of the 2 groups were all negative. Ki67 in the 2 groups were shown to be 90% and had no significant difference (×100).

Table 2.

The IC50 Values of THP in various cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA or controls.

| Cell lines | THP (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| HIF-1α shRNA | 0.0707± 0.0079* |

| NC shRNA | 0.0946± 0.0006 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 0.0985 ± 0.0095 |

P < 0.01, compared with the controls.

Table 3.

Tumorigenicity of cells treated with HIF-1α shRNA or control shRNA in NOD/SCID mice

| Cell counts | HIF-1α shRNA | NC shRNA |

|---|---|---|

| 106 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| 105 | 1/4 | 3/4 |

| 104 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

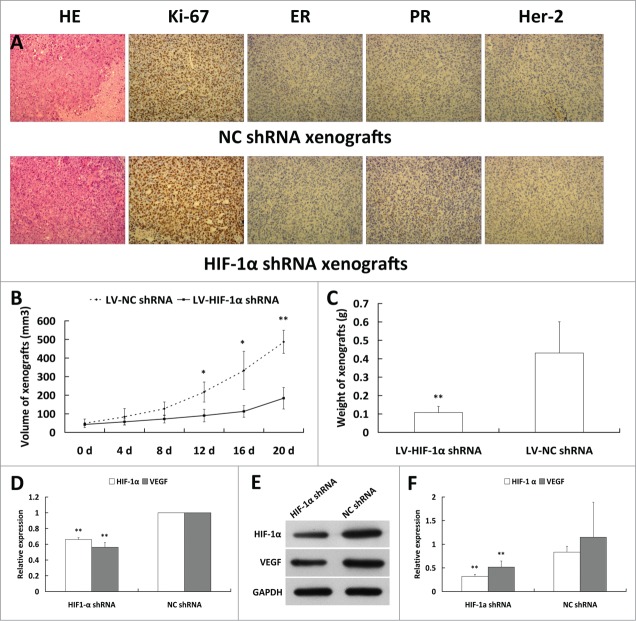

Lentivirus-mediated HIF-1α shRNA decreases the expression of HIF-1α and its downstream genes and inhibits the growth of xenograft tumors in vivo

To further investigate the therapeutic potential of HIF-1α shRNA recombinant lentivirus in triple negative breast cancer in vivo, we implanted untreated MDA-MB-231 without any lentivirus to the each armpit fat pads subcutaneously in 5-week old nude mice respectively and the recombinant lentivirus containing HIF-1α shRNA and NC shRNA were injected intratumorally to each of bilateral xenografts. The growth of tumors was significantly inhibited in HIF-1α shRNA treated group in comparison with the NC shRNA treated group. The weight of HIF-1α shRNA xenografts showed a fold4- decrease compared with that of the NC shRNA. We also found that HIF-1α and VEGF expression at both mRNA and protein levels in the tumor tissue were decreased in HIF-1α shRNA treated group in comparison with that of NC shRNA (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

HIF-1α shRNA inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (A) H & E stain and immunohistochemical assay for xenografts tissues. More necrotic tissue was shown in NC shRNA xenografts by H & E stain for more rapidly proliferation. ER, PR and Her2 of 2 groups are all negative. Ki67 in 2 groups are shown to be 90% and have no significant difference (×100). (B) Measure the xenografts every 4 d post letivirus injection and calculate the volume of xenografts. The growth of tumors was significantly inhibited in HIF-1α shRNA group in comparison with NC shRNA group. (C) The weight of HIF-1α shRNA xenografts showed a fold4- decrease compared with that of the NC shRNA. (D) HIF-1α and VEGF expressions at mRNA level in xenografts of HIF-1α shRNA group were significantly decreased compared to NC shRNA group by quantitive real-time PCR. E: HIF-1α and VEGF expressions at protein level in xenografts of 2 groups using Western blot. F: HIF-1α and VEGF expressions at protein level in HIF-1α shRNA group were significantly decreased compared with the NC shRNA group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

The present study was designed to develop a novel HIF-1α-targeted therapy for TNBC. Although HIF-1α is considered an attractive target for the development of cancer therapies, it has been regarded as “undruggable.”21,22,24 Considering several advantages of lentivirus vectors, we explored the therapeutic potential of HIF-1α targeting by lentivirus in vitro and in vivo. Our results showed that HIF-1α shRNA lentivirus effectively inhibited cancer growth.

It has been reported that TNBC is a biologically heterogeneous group of breast cancers characterized by the lack of expression of ER, PR, and HER2 TNBCs, accounting for 12–17% of all breast cancers, and representing one of the most aggressive forms of the disease with short relapse-free survival time and poor survival rate.25 TNBC lacks validated therapeutic targets compared with other breast cancer subtypes;26 various efforts have been devoted to developing novel therapies for the disease. Several targeted therapies including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), and angiogenesis ligands and receptors, are currently under preclinical and/or clinical investigations.27,28

MDA-MB-231 is a well-studied TNBC cell line with highly aggressive characteristics. Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) are a subpopulation within breast cancer cells that are CD44+CD24−/low and play a significant role in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and recurrence.29–31 In our previous study, we found that the percentage of BCSCs reachs 71.52–74.39% in MDA-MB-231 cells, which suggests that MDA-MB-231 is a suitable model to identify new therapeutic strategies for TNBC and to better understand the role of BCSCs. 24 Xenografts produced by MDA-MB-231 with subcutaneous injection showed poorly differentiated and highly malignant tumors. In our study, the results of H & E staining and immunohistochemistry assay on xenografts in vivo confirmed these results.

It has been well documented that HIF-1 is a master transcript factor in oxygen homeostasis and regulates the expression of over 70 genes involved in tumorigenesis and tumor progression, including cancer cells survival, proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, chemoresistance, and angiogenesis.32 The increased HIF-1α levels, are associated with increased mortality in patients with various cancers. In lymph node negative patients with breast cancer, the HIF-1α overexpression is a negative prognostic factor and correlates with increased tumor proliferation.33 HIF-1α has been considered as an attractive molecular target for the development of novel cancer therapies.34,35

Lentiviral vector has recently received considerable attention because it infects non-dividing cells and has a target gene integrated into the genome of target cells with long-term expression and less immune response. Therefore, in the present study, we explored therapeutic potential of lentivirus targeting HIF-1α in the treatment of TNBCs. Our results showed that stable downregulation of HIF-1α promoted both early and late apoptosis. Previous studies have suggested that HIF-1α can either induce or prevent apoptosis.36 For instance, in pancreatic cancer cell lines, high concentrations of HIF-1α were seen at normoxia, which is a result of activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, rather than hypoxia. These cells show more resistance to apoptosis caused by hypoxia and glucose deprivation.36,37 HIF-1 may also have an anti-apoptotic function because cells with high amounts of HIF-1 are more resistant to hypoxia-induced apoptosis.38 It has been suggested that hypoxia alters cellular proliferation in 2 distinct ways by modulating apoptosis and cell cycle progression.39 HIF-1 could regulate cell cycle progression under hypoxia through different mechanisms.40 In the present study, we found that stable downregulation of HIF-1α reduced the number of cells in G1 phase and increase those in G2/M phase. These changes may account for the increased chemosensitivity of the HIF-1α shRNA stably transfected cells.

Hypoxia in tumors causes resistance to a variety of chemotherapeutic agents in many cancer cell lines. Multidrug resistance (MDR) is a main cause of breast cancer chemotherapy failure.41 Hypoxia induces cellular adaptations which contribute to cancer progression and chemoresistance, with one of these adaptations being the expression of multidrug resistance proteins such as ABC transporters.42 Evidence of MDR-1 or MRP1 upregulation through HIF-1 under hypoxia has recently been highlighted.43,44 In the present study, we observed increased chemosensitivity to THP in HIF-1α shRNA-treated cells, compared with NC shRNA treated or untreated cells, supporting the notion that the combination of gene therapy and chemotherapy may be a new hope for TNBC treatment.45 Recently, a constitutively active HIF-1α transgene mediated by adenovirus has been tested as a therapeutic strategy in no-option critical limb ischemia patients in a phase I dose-escalation study and was shown well tolerated.46 Based on our results from the present study, we speculate that stable downregulation of HIF-1α by lentivirus could be a novel effective and safe gene therapy approach to TNBC treatment.

Materials and Methods

Breast cancer cell line and cell culture

Human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 was obtained from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C and 5% of CO2.

Construction of recombinant lentivirus

The shRNA sequences were as follows: negative control shRNA (NC shRNA): 5′- TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTC-3′; HIF-1α shRNA: 5′-GAAACTCTTCCAAGCAATTTT-3′. Knockdown (KD) of HIF-1α expression by lentivirus mediated shRNA in MDA-MB-231 was performed according to instructions from the manufacturer (Suzhou Genepharma Corporation Ltd., Suzhou, China).

To prepare lentivirus transduction particles, HEK293T cells (Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) in 100-mm cell culture dishes were co-transfected with 2 µg of pCMV-R8.91 harboring Gag and Pol genes, 0.2 µg of pMD.G containing the gene for expressing the vesicular stomatitis virus envelope glycoprotein (i.e., VSV-G), and 2 µg of pLKO.1 bearing specific shRNAs. The cells were incubated in transfection medium (OPTI/MEM, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 6 h, followed by incubation in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% bovine serum albumin for 24 h. The culture medium containing lentivirus particles was collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until use.

Infection of cells with lentivirus carrying HIF-1α shRNA

For lentivirus transduction, MDA-MB-231 cells at approximately 80% confluency were infected with lentivirus-bearing specific shRNAs in growth medium containing 8 µg/ml of polybrene for 24 h. For quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of HIF-1α mRNA and Western blotting for HIF-1α protein, the infected MDA-MB-231 cells were subcultured for 3 d in growth medium containing 2 µg/ml of puromycin.

Quantitative PCR

The total RNA from cells and tissues was prepared using TriPure (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA from total RNA. The real-time PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green I reagent (Invitrogen) on Mx3000P (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The mRNA level was analyzed by 2−ΔΔCtvalues. The primer sequences used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in the analysis of expression of target genes

| Target genes | Primer Sequences |

|---|---|

| Hif-1α | F: 5'-GGCGCGAACGACAAGAAAAAG-3'R:5'-CCTTATCAAGATGCGAACTCACA-3' |

| Vegf | F: 5'-CAGCGCAGCTACTGCCATCCAATCGAGA-3' R:5'-GCTTGTCACATCTGCAAGTACGTTCGTTTA-3' |

| Gadph | F: 5'-CAGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCA-3'R: 5'-TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA-3' |

Western blotting analysis

The cells and tissue samples were collected and lysed with the RIPA lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% TritonX-100, and 100 mg/ml PMSF (Beyotime, Wuhan, China). The total protein concentration was measured by the BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The samples with equal amount of total protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). Following blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the membranes were probed with antibodies against HIF-1α and VEGF (CST, Boston, MA, USA) at 4°C for 12 h and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (CST, Boston, MA, USA) for 1 h. The protein bands of interest were visualized using an electrochemiluminescence kit (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) and exposed to X-ray films (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). The bands were scanned using Bio-5000Plus (Microtek, Xinzhu, Taiwan) and quantitation was determined as the optical densities of the bands using IPP Image software 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

After culture in puromycin-containing growth medium for 3 passages, the lentivirus-infected MDA-MB-231 were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates (5,000 cells/well) for the CCK8 cell proliferation assay (Tojindo, Japan). Briefly, the cells were incubated with the CCK8 reagent at 37°C for 1 h, and absorbance (450 nm) was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo, Franklin, MA, USA) every 24 h of culture for 12 d

Cell migration assay

For the wound healing assay, the cells were grown in complete culture medium to monolayer confluence in 24-well tissue culture plates. After scratching with a 20-μL sterile pipette tip, the cells were cultured with serum-free culture medium. At 24 and 48 h after scratching, the cells were washed with PBS solution 3 times, observed and photographed. The results were calculated with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Transwell invasion assay

For the Transwell assays, Matrigel (BD Biosciences, diluted 1:3 in pre-chilled serum-free media) was coated onto each insert of 24-Tranwell invasion plate (8-µm pore size; Millipore, Boston, MA, USA ) and incubated for 2 h. 50,000 cells were seeded in the top chamber, in serum-free media; the bottom chamber contained 10% FBS in DMEM medium. After 48 h, the cells from the upper chamber were removed using a cotton swab and the cells invaded through Matrigel were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min and then stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 20 min. Images of the invading cells were photographed using an inverted 20× microscope and the total cell numbers were counted and quantified by Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

In vitro cytotoxicity of Pirarubicin (THP)

The cytotoxicity of treatments was determined by the CCK8 assay. The cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at the density of 5 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37˚C with 5% CO2. The next day, the culture medium was replaced with 200 µl of fresh complete medium and then the cells were treated with different concentrations (0, 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16, 0.32, 0.64, and 1.28 µg/mL) of Pirarubicin (THP, Shenzhen Main Luck Pharmaceuticals Inc.., Shenzhen, China). The fresh Pirarubicin solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared with ultra-pure water immediately before the treatment of the cells. After 48 h of incubation, the culture medium was removed and the cells were incubated with the CCK8 solution (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan) for 4 h at 37°C. Finally, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo). Measurements were performed in triplicate for each treatment. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was then determined using sigmoidal fitting (Boltzmann function) of the concentration–response curve.

Apoptosis analysis

Apoptosis assay was performed using Guava Nexin Reagent (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the cells were collected and adjusted at a density of 2×105 to 1×106 cells/mL. The cells (100 μL) were incubated at dark with 100 μL Guava Nexin Reagent for 20 min at room temperature and then analyzed by flow cytometry (Guava System, Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) as described previously.24

Cell cycle analysis

The cell cycle distribution was detected using Guava cell cycle reagent (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the cells were collected, washed with PBS, centrifuged at 450 g for 5 min, and fixed in 500 μL PBS containing pre-cold 70% ethanol at 4°C for 72 h. The fixed cells were then washed with PBS, incubated with Guava cell cycle reagent for 30 min and then analyzed by flow cytometry (Guava System, Millipore, Boston, MA, USA) as described previously.24

Animal experiments

Male 6-week-old NOD/SCID mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China. The mice were fed with standard diet and tap water ad libitum and housed in plastic cages at 21 ± 2°C and 12h-12h light-dark cycle, with relative humidity of 40–50%. The mice were allowed to acclimate for one week prior to study. The cells stably transfected with shHIF-1α or control (106, 105, or 104) were suspended in 100 μL of the mixture of PBS and Matrigel (8:1) and then subcutaneously injected into each side of armpit fat pads of the NOD/SCID mice and tumor formation rates were calculated for 4 weeks (n = 4 ). At 4 weeks post cells injection, the xenografts were isolated and fixed in paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding. The tumor tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Thermo Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI, USA). The protein levels of ER, PR, Her2, and Ki67 in tumor tissues were analyzed by immunohistochemical assay and the images were obtained with microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

To explore the therapeutic effects of HIF-1α shRNA recombinant lentivirus on breast cancer in vivo, when the length of primary MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors reached about 5 mm, an intratumoral injection was performed with 108 lentivirus in 100 μL with sh-NC and sh-HIF-1α into each side of xenografts (n=10 ). The tumor size was measured every 4 d post injection and calculated as follows: (Width2×Length) /2 (mm3)

At 3 weeks post cells injection, the nude mice were killed by cervical dislocation and xenografts were harvested, weighed and lysed. The mRNA and proteins were analyzed by real-time PCR and western blot, respectively.

Ethics statement

The animal study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, Guangzhou, China.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (±s ). The differences in means between groups were analyzed using Student's t-test or ANOVA as appropriate. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Funding Statement

This work was sponsored by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81101749).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Ban KA, Godellas CV. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2014; 23:409–22; PMID:24882341; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.soc.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64:9–29; PMID:24399786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64:52–62; PMID:24114568; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer M, van Dijck JA, Bult P, Borm GF, Tjan-Heijnen VC. Breast cancer prognosis and occult lymph node metastases, isolated tumor cells, and micrometastases. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102:410–25; PMID:20190185; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/djq008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard-Marty C, Cardoso F, Piccart MJ. Facts and controversies in systemic treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 2004; 9:617–32; PMID:15561806; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1634/theoncologist.9-6-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Ruijter TC, Veeck J, de Hoon JP, van Engeland M, Tjan-Heijnen VC. Characteristics of triple-negative breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011; 137:183–92; PMID:21069385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00432-010-0957-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav BS, Sharma SC, Chanana P, Jhamb S. Systemic treatment strategies for triple-negative breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5:125–33; PMID:24829859; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barsoum IB, Koti M, Siemens DR, Graham CH. Mechanisms of hypoxia-mediated immune escape in cancer. Cancer Res 2014; (24):7185-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettersen EO, Ebbesen P, Gieling RG, Williams KJ, Dubois L, Lambin P, Ward C, Meehan J, Kunkler IH, Langdon SP, et al.. Targeting tumour hypoxia to prevent cancer metastasis. From biology, biosensing and technology to drug development: the METOXIA consortium. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2014; 27:1–33; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/14756366.2014.966704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxiainducible factor-1. J Biol Chem 1995;270:1230–7; PMID:7836384; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salceda S, Beck I, Caro J. Absolute requirement of aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein for gene activation by hypoxia. Arch Biochem Biophys 1996; 334:389–94; PMID:8900415; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/abbi.1996.0469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu L, Marti GP, Wei X, Zhang X, Zhang H, Liu YV, Nastai M, Semenza GL, Harmon JW. Age-dependent impairment of HIF-1alpha expression in diabetic mice: Correction with electroporation-facilitated gene therapy increases wound healing, angiogenesis, and circulating angiogenic cells. J Cell Physiol 2008; 217:319–27; PMID:18506785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.21503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibuya M. VEGF-VEGFR Signals in Health and Disease. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2014; 22:1–9; PMID:24596615; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4062/biomolther.2013.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semenza GL. Signal transduction to hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Pharmacol 2002; 64:993–8; PMID:12213597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01168-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agani F, Jiang BH. Oxygen-independent regulation of HIF-1: novel involvement of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:245–251; PMID:23297826; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1568009611313030003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subtil FS, Wilhelm J, Bill V, Westholt N, Rudolph S, Fischer J, Scheel S, Seay U, Fournier C, Taucher-Scholz G, et al.. Carbon ion radiotherapy of human lung cancer attenuates HIF-1 signaling and acts with considerably enhanced therapeutic efficiency. FASEB J. 2014;28:1412–21; PMID:24347608; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.13-242230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warfel NA, El-Deiry WS. HIF-1 signaling in drug resistance to chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:3021–8; PMID:24735366; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/0929867321666140414101056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miura Y, Ohnami S, Yoshida K, Ohashi M, Nakano M, Fukuhara M, Yanagi K, Matsushita A, Uchida E, Asaka M, et al.. Intraperitoneal injection of adenovirus expressing antisense K-ras RNA suppresses peritoneal dissemination of hamster syngeneic pancreatic cancer without systemic toxicity. Cancer Lett 2005; 218:53–62; PMID:15639340; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trujillo MA, Oneal MJ, Davydova J, Bergert E, Yamamoto M, Morris JC 3rd. Construction of an MUC-1 promoter driven, conditionally replicating adenovirus that expresses the sodium iodide symporter for gene therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2009; 11:R53; PMID:19635153; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young LS, Searle PF, Onion D, Mautner V. Viral gene therapy strategies: from basic science to clinical application. J Pathol 2006; 208:299–318; PMID:16362990; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/path.1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monti E, Gariboldi MB. HIF-1 as a target for cancer chemotherapy, chemosensitization and chemoprevention. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011; 4:62–77; PMID:20958262; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/1874467211104010062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meijer TW, Kaanders JH, Span PN, Bussink J. Targeting hypoxia, HIF-1, and tumor glucose metabolism to improve radiotherapy efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5585–94; PMID:23071360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilczynski J, Duechler M, Czyz M. Targeting NF-κB and HIF-1 pathways for the treatment of cancer: part II. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2011;59:301–7; PMID:21625847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, LI Q, Li S, Chen B, Zou H. HIF-1α decoy oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit HIF-1α signaling and breast cancer proliferation. Int J Oncol 2015; 46: 215–22; PMID:25334080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman LA, Reis-Filho JS, Morrow M, Carey LA, King TA. The 2014 Society of Surgical Oncology Susan G. Komen for the Cure Symposium: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015; 22(3):874-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis JS. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1938–48; PMID:21067385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMra1001389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleator S, Heller W, Coombes RC. Triple-negative breast cancer: therapeutic options. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 235–44; PMID:17329194; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70074-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohn J, Liu S, Parinyanitikul N, Lee J, Hortobagyi GN, Mills GB, Ueno NT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. cMET Activation and EGFR-Directed Therapy Resistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J cancer 2014; 5: 745–53; PMID:25368674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7150/jca.9696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF: Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100:3983–8; PMID:12629218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0530291100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li S, Li Q. Cancer stem cells and tumor metastasis. Int J Oncol 2014; 44:1806–12; PMID:24691919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S, Li Q. Cancer stem cells, lymphangiogenesis, and lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Lett 2015; 357(2):438-47. pii: S0304-3835(14)00756-3. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.013 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semenza GL. HIF-1 and human disease: one highly involved factor. Genes Dev 2000; 14:1983–91; PMID:10950862 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bos R, van der Groep P, Greijer AE, Shvarts A, Meijer S, Pinedo HM, Semenza GL, van Diest PJ, van der Wall E. Levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha independently predict prognosis in patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma. Cancer 2003; 97:1573–81; PMID:12627523; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.11246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin SK, Diamond P, Gronthos S, Peet DJ, Zannettino AC. The emerging role of hypoxia, HIF-1 and HIF-2 in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2011; 25:1533–42; PMID:21637285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/leu.2011.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamlah F, Eul BG, Li S, Lang N, Marsh LM, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Rose F, Hänze J. Intravenous injection of siRNA directed against hypoxia-inducible factors prolongs survival in a Lewis lung carcinoma cancer model. Cancer Gene Ther 2009; 16:195–205; PMID:18818708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greijer AE, van der Wall E. The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57:1009–14; PMID:15452150; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/jcp.2003.015032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akakura N, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, Suzuki A, Wang J, Chen J, Niizeki H, Kawamura Ki, Hosokawa M, Asaka M. Constitutive expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α renders pancreatic cancer cells resistant to apoptosis induced by hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res 2001; 61:6548–54; PMID:11522653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Yu Z. siRNA Targeting HIF-1α Induces Apoptosis of Pancreatic Cancer Cells through NF-κB-independent and –dependent Pathways under Hypoxic Conditions. Anticancer Res 2009; 29: 1367–72; PMID:19414389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kosaka H, Kamiike W, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Prevention of hypoxia-induced cell death by Bcl−2 and Bcl−xL. Nature 1995; 374:811–3; PMID:7723826; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/374811a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goda N, Ryan HE, Khadivi B, McNulty W, Rickert RC, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α is essential for cell cycle arrest during hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23:359–69; PMID:12482987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.23.1.359-369.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu WD, Hu ZM, Shang MJ, Zhao DJ, Zhang CW, Hong DF, Huang DS. Cordycepin down-regulates multiple drug resistant (MDR)/HIF-1α through regulating AMPK/mTORC1 signaling in GBC-SD gallbladder cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:12778–90; PMID:25046749; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms150712778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stavrovskaya AA, Stromskaya TP. Transport proteins of the ABC family and multidrug resistance of tumor cells. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008; 73:592–604; PMID:18605983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1134/S0006297908050118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen L, Feng P, Li S, Long D, Cheng J, Lu Y, Zhou D. Effect of hypoxiainducible factor-1alpha silencing on the sensitivity of human brain glioma cells to doxorubicin and etoposide. Neurochem Res 2009; 34:984–90; PMID:18937067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11064-008-9864-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Comerford KM, Wallace TJ, Karhausen J, Louis NA, Montalto MC, Colgan SP. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent regulation of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene. Cancer Res 2002; 62:3387–94; PMID:12067980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao H, Wang G, Gu L, Huang S, Chen X, Li Y, Cai S. HIF-1α siRNA and Cisplatin in Combination Suppress Tumor Growth in a Nude Mice Model of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2012; 13:473–7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.2.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajagopalan S, Olin J, Deitcher S, Pieczek A, Laird J, Grossman PM, Goldman CK, McEllin K, Kelly R, Chronos N. Use of a constitutively active hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transgene as a therapeutic strategy in no-option critical limb ischemia patients: phase I dose-escalation experience. Circulation 2007;115:1234–43; PMID:17309918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]