Abstract

The anti-arrhythmic agent amiodarone (AD) is associated with numerous adverse effects, but serious liver disease is rare. The improved safety of administration of daily low doses of AD has already been established and this regimen is used for long-term medication. Nevertheless, asymptomatic continuous liver injury by AD may increase the risk of step-wise progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. We present an autopsy case of AD-induced liver cirrhosis in a patient who had been treated with a low dose of AD (200 mg/d) daily for 84 mo. The patient was a 85-year-old male with a history of ischemic heart disease. Seven years after initiation of treatment with AD, he was admitted with cardiac congestion. The total dose of AD was 528 g. Mild elevation of serum aminotransferase and hepatomegaly were present. Liver biopsy specimens revealed cirrhosis, and under electron microscopy numerous lysosomes with electron-dense, whorled, lamellar inclusions characteristic of a secondary phospholipidosis were observed. Initially, withdrawal of AD led to a slight improvement of serum aminotransferase levels, but unfortunately his general condition deteriorated and he died from complications of pneumonia and renal failure. Long-term administration of daily low doses of AD carries the risk of progression to irreversible liver injury. Therefore, periodic examination of liver function and/or liver biopsy is required for the management of patients receiving long-term treatment with AD.

Keywords: Amiodarone, Liver cirrhosis, NASH, NAFLD, Liver biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Amiodarone (AD) is a cationic, amphophilic, iodinated benzofuran derivative primarily used for the treatment of refractory ventricular tachyarrythmias[1]. Although AD has been used since 1962, it causes various side effects affecting the lung, thyroid gland, cornea, peripheral nerves, and liver[1-3]. In early clinical trials, higher maintenance doses of AD (300-800 mg/d) caused serious side effects in the first year of therapy, and these patients required drug withdrawal[1-6]. In the last two decades, several investigators have shown that daily lower doses of AD (< 200 mg/d) are better tolerated but still possess appreciable efficacy in serious cardiac arrhythmias[4-6].

The hepatotoxicity associated with AD is manifested as an asymptomatic and transient elevation of serum aminotransferase[2,3,6-8]. Fortunately, the vast majority of these events are reversible after discontinuation of the medication[2,3,6]. The safer schedule of administration of low doses daily may contribute to reducing the incidence of serious hepatic adverse effects. The histologic appearance of AD-induced liver disease shares several features with that of alcoholic hepatitis. Asymptomatic continuous liver injury by AD may increase the risk of step-wise progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[7-19]. This implies that severe morphological alterations of the liver may coexist with very mild symptoms in patients receiving long-term treatment with daily low doses of AD. We present herein an autopsy case of AD-induced liver cirrhosis in a patient treated with a low dose of AD daily for 84 mo. We discuss the risk of progression to irreversible liver injury during administration of AD and the value of liver biopsy for patients receiving long-term treatment with a low dose of AD daily.

CASE REPORT

A 85-year-old male with a history of ischemic heart disease was being treated with AD for continuing symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias. He was admitted with cardiac congestion in December 2001, 7 years after administration of AD had begun. There was no history of alcohol abuse, obesity or diabetes mellitus. Serological screening and PCR examination for hepatitis viruses were all negative. There were no signs of autoimmune hepatitis. His initial dose of AD was 400 mg daily for 17 d, which was then reduced to a maintenance dose of 200 mg daily. The patient had received continuous medication with AD for 84 mo. On physical examination, corneal opacities were found. No skin discoloration or neuronal symptoms were seen.

Serum total bilirubin was 1.2 mg/dL, aspartate amino-transferase 81 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 35 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 452 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 210 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 848 IU/L, and prothrombin time activity 59%. Up to that time, no elevation of serum aminotransferase or signs suggesting liver dysfunction had been observed.

The chest radiograph revealed cardiac enlargement and bilateral pleural effusion without findings of interstitial fibrosis. Abdominal ultrasonography showed enlargement of the left lobe of the liver relative to atrophy of the right lobe, and an irregular liver surface. In addition, ascites and mild splenomegaly were seen. An unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the upper abdomen showed an abnormally high density of liver tissue [111.8 Hounsfield units (HU); normal range 30-70 HU] (Figure 1). A percutaneous liver biopsy examination revealed micronodular cirrhosis accompanied by findings of alcoholic liver disease (Figure 2). Fibrous septa containing proliferating bile ductules and neutrophil polymorphs connected adjacent portal areas (Figure 2). Scattered foci of hepatocellular necrosis with neutrophilic infiltration were observed (Figure 2). Electron microscopic observations showed that hepatocytes contained numerous lysosomes with electron-dense, whorled, lamellar inclusions (LI), characteristic of a secondary phospholipidosis (Figure 3). The findings of the CT scan and the liver biopsy indicated that AD-induced liver cirrhosis was responsible for the hepatotoxicity and his poor general condition. Administration of AD was discontinued. The total dose of AD administered over the 84 mo was 528 g.

Figure 1.

An unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the upper abdomen. The liver has a greatly increased density (111.8 HU).

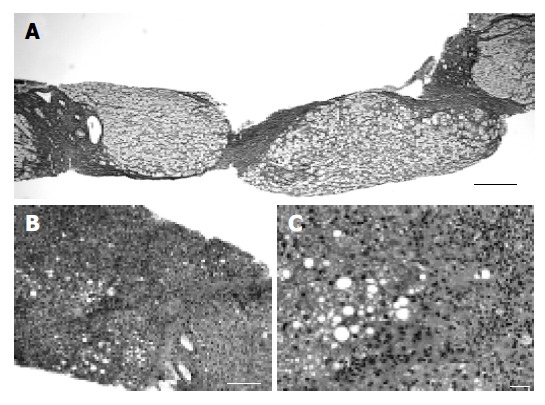

Figure 2.

Microscopic features of the liver biopsy specimen. A: Micronodular cirrhosis has become established (silver impregnation, scale bar = 200 µm); B: Low power view of the liver biopsy specimen (hematoxylin and eosin stain, scale bar = 200 µm). Fatty degeneration and marked fibrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration were observed; C: High power view of the liver biopsy specimen (hematoxylin and eosin stain, scale bar = 20 µm). Foci of hepatocellular necrosis and dense fibrosis with neutrophilic infiltration were observed. Hepatocytes showed both the microvesicular and macrovesicular types of steatosis.

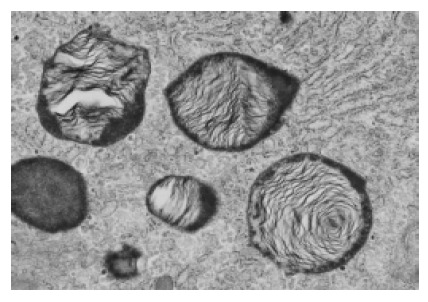

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrograph of the biopsy specimen with lamellated inclusions in the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte (original magnification ×20 000).

Initially, withdrawal of AD led to a slight improvement in the serum aminotransferase level and the ascites. The CT density of the liver decreased to 97.2 HU in February 2002, whereas no significant improvement was observed in the size of the liver. Unfortunately, his general condition deteriorated as a result of complications of pneumonia and renal failure. He died in April 2002.

Autopsy was performed on April 22nd, 2002. Micros-copically, features affected by AD were observed in the follicular epithelial cells of the thyroid gland and in the liver. Notably, there were no histological findings suggesting AD-induced pulmonary toxicity, which is more common and often more serious than hepatotoxicity, whereas both his lungs revealed congestion with pneumonic foci.

We compared the light-microscopic and electron-microscopic findings for the biopsy (December 2001) and autopsy (April 2002) materials (Table 1). Light microscopy of the autopsy materials also revealed micronodular cirrhosis. The biopsy material showed both microvesicular and macrovesicular steatosis, but the autopsy material showed only microvesicular steatosis. The number of hepatocytes with Mallory bodies was similar to that of the biopsy specimen. We counted the number of lysosomes with LI relative to the total number of lysosomes in the liver. The incidence was relatively lower in the autopsy specimen compared with the biopsy specimen (Table 1). Unfortunately, we could not assess the tissue concentration of AD.

Table 1.

Comparison of CT density and light and electron micro-scopic findings between biopsy and autopsy specimens of the liver

| Biopsy | Autopsy | |

| CT density (HU) | 111.8 | 97.2 |

| Light microscopic findings | ||

| Nodular formation | Micronodular | Micronodular |

| Fibrosis | Dense | Dense |

| Steatosis | Macro/microvesicular | Microvesicular |

| Infiltration of inflammatory cells | Moderate | Moderate |

| Electron microscopic findings | ||

| Number of lysosomes with | 992/2 726 (36.4%) | 862/2 578 (33.4%) |

| lamellar inclusion/total | ||

| number of lysosomes (%)1 |

Counts were performed of 10 fields (×18 000) of five blocks for each material.

DISCUSSION

The true incidence of AD-induced liver cirrhosis is obscure, since liver biopsy has not been performed routinely in AD-treated patients. Almost all cases of AD-induced liver cirrhosis have been reported in patients receiving higher maintenance doses[15,16], and only five cases arising from administration of daily low doses have been described in the literature (Table 2)[12-14,18,19]. Some investigators have speculated that the total cumulative dose might be more important in estimating the risk of irreversible liver injury[10,15,16]. The cumulative doses of the patients previously reported ranged from 165 to 213 g, with a duration of treatment of 12-48 mo. The present patient had been treated with 200 mg of AD daily for 84 mo, with a total cumulative dose of 528 g. Even though this dosage is greater than that in previous reports, hepatic abnormalities were not detected during the course of treatment. As asymptomatic progression of liver disease might occur more frequently in patients receiving long-term treatment with AD, periodic examination of liver function and/or biopsy should be performed to detect liver injury. Gilinsky et al[9] described that drug withdrawal was insufficient to restore liver function, if irreversible liver damage had already occurred. Early histological examination for hepatic abnormalities is helpful to warn off irreversible liver changes.

Table 2.

Summary of published cases of cirrhosis after long-term administration of daily low doses of AD

| No | Reference | Age (yr) | Duration (mo) | Cumulative dose (g) | Outcome |

| 1 | Present case | 85 | 84 | 528 | Dead |

| 2 | 12 | 76 | 48 | Not described | Dead |

| 3 | 13 | 68 | 13.5 | 165 | Dead |

| 4 | 14 | 77 | 12 | 202 | Dead |

| 5 | 18 | 79 | 33 | 200 | Dead |

| 6 | 19 | 83 | 35 | 213 | Non-fatal |

We suggest that genetic background might also be important in determining the risk of progression of NAFLD in patients receiving long-term treatment with AD. It is well known that steatosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) can be induced by drugs such as tamoxifen, some anti-retroviral agents and AD[20-22]. These drugs inhibit the mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids (causing steatosis) and respiration[20,23]. Inhibition of respiration decreases ATP and also increases the mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In hepatocytes, ROS and lipid peroxidation products further impair the respiratory chain, either directly or indirectly through oxidative damage to the mitochondrial genome. Mitochondrial dysfunction can also lead to apoptosis or necrosis, depending on the energy status of the cell. ROS and lipid peroxidation products also activate stellate cells, thus resulting in fibrosis. Finally, ROS and lipid peroxidation increase the generation of several cytokines (TNF-α, TGF-β, and Fas ligand) that play various roles in the pathogenesis of drug-induced NASH[20,23].

Some investigators have postulated that in insulin resistance the combination of elevated plasma concentrations of glucose and fatty acids promotes hepatic fatty acid synthesis and impairs oxidation, leading to hepatic steatosis[20,24,25]. Several polymorphisms in genes related to insulin resistance appear to be associated with the severity of steatosis[25-29]. We examined a few polymorphisms in the TNF-α, HFE, CYP2E1, and IL-10 genes, but the susceptibility alleles were not present in the patient (data not shown). However, we are now undertaking a genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism study in patients with drug-induced NASH[20]. Further, several experimental and clinical studies suggest that a number of drugs could be useful for the prevention and/or treatment of NASH. These genetic and clinical approaches may help increase the safety of the long-term administration of AD.

Footnotes

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

Supported by Grants-in-Aid No. 16590289, 16790211 and 16790212, and “Open Research Center” Project for Private Universities: Matching fund Subsidy (2004-2008), from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan

References

- 1.Mason JW. Amiodarone. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:455–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702193160807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowey PR, Friehling TD, Marinchak RA, Sulpizi AM, Stohler JL. Safety and efficacy of amiodarone. The low-dose perspective. Chest. 1988;93:54–59. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerin NZ, Aragon E, Faitel K, Frumin H, Rubenfire M. Long-term efficacy and toxicity of high- and low-dose amiodarone regimens. J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;29:418–423. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1989.tb03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicklas JM, McKenna WJ, Stewart RA, Mickelson JK, Das SK, Schork MA, Krikler SJ, Quain LA, Morady F, Pitt B. Prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose amiodarone in patients with severe heart failure and asymp-tomatic frequent ventricular ectopy. Am Heart J. 1991;122:1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90466-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG, Singh BN, Lewis HD, Deedwania PC, Massie BM, Colling C, Lazzeri D. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:77–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vorperian VR, Havighurst TC, Miller S, January CT. Adverse effects of low dose amiodarone: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:791–798. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon JB, Manley PN, Brien JF, Armstrong PW. Amiodarone hepatotoxicity simulating alcoholic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:167–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198407193110308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poucell S, Ireton J, Valencia-Mayoral P, Downar E, Larratt L, Patterson J, Blendis L, Phillips MJ. Amiodarone-associated phospholipidosis and fibrosis of the liver. Light, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic studies. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:926–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilinsky NH, Briscoe GW, Kuo CS. Fatal amiodarone hepatoxicity. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bach N, Schultz BL, Cohen LB, Squire A, Gordon R, Thung SN, Schaffner F. Amiodarone hepatotoxicity: progression from steatosis to cirrhosis. Mt Sinai J Med. 1989;56:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison RF, Elias E. Amiodarone-associated cirrhosis with hepatic and lymph node granulomas. Histopathology. 1993;22:80–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tordjman K, Katz I, Bursztyn M, Rosenthal T. Amiodarone and the liver. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:411–412. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-3-411_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinder HM, Love JC, Wexler R. Amiodarone hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:318–319. doi: 10.1056/nejm198601303140516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaharty KK, Chase SL, Yaghsezian HM, Rubin R. Hepatotoxicity associated with amiodarone therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 1989;9:39–44. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1989.tb04102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis JH, Ranard RC, Caruso A, Jackson LK, Mullick F, Ishak KG, Seeff LB, Zimmerman HJ. Amiodarone hepatotoxicity: prevalence and clinicopathologic correlations among 104 patients. Hepatology. 1989;9:679–685. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis JH, Mullick F, Ishak KG, Ranard RC, Ragsdale B, Perse RM, Rusnock EJ, Wolke A, Benjamin SB, Seeff LB. Histopathologic analysis of suspected amiodarone hepatotoxicity. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90076-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babany G, Mallat A, Zafrani ES, Saint-Marc Girardin MF, Carcone B, Dhumeaux D. Chronic liver disease after low daily doses of amiodarone. Report of three cases. J Hepatol. 1986;3:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(86)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singhal A, Ghosh P, Khan SA. Low dose amiodarone causing pseudo-alcoholic cirrhosis. Age Ageing. 2003;32:224–225. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guigui B, Perrot S, Berry JP, Fleury-Feith J, Martin N, Métreau JM, Dhumeaux D, Zafrani ES. Amiodarone-induced hepatic phospholipidosis: a morphological alteration independent of pseudoalcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1988;8:1063–1068. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fromenty B, Robin MA, Igoudjil A, Mansouri A, Pessayre D. The ins and outs of mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:121–138. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fromenty B, Fisch C, Labbe G, Degott C, Deschamps D, Berson A, Letteron P, Pessayre D. Amiodarone inhibits the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids and produces microvesicular steatosis of the liver in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:1371–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lettéron P, Sutton A, Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Pessayre D. Inhibition of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein: another mechanism for drug-induced steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2003;38:133–140. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, Romanelli AJ, Shulman GI. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day CP. The potential role of genes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:673–691, xi. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell GC. Drugs and steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:185–194. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-30106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Dongiovanni P, Santorelli G, Branchi A, Taioli E, Fiorelli G, Fargion S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter polymorphisms and insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:274–280. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George DK, Goldwurm S, MacDonald GA, Cowley LL, Walker NI, Ward PJ, Jazwinska EC, Powell LW. Increased hepatic iron concentration in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with increased fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidali M, Stewart SF, Rolla R, Daly AK, Chen Y, Mottaran E, Jones DE, Leathart JB, Day CP, Albano E. Genetic and epigenetic factors in autoimmune reactions toward cytochrome P4502E1 in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:410–419. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grove J, Daly AK, Bassendine MF, Gilvarry E, Day CP. Interleukin 10 promoter region polymorphisms and susceptibility to advanced alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 2000;46:540–545. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]