Abstract

This study aims to identify effective gene networks and prognostic biomarkers associated with estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer using human mRNA studies. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis was performed with a complex ER+ breast cancer transcriptome to investigate the function of networks and key genes in the prognosis of breast cancer. We found a significant correlation of an expression module with distant metastasis-free survival (HR = 2.25; 95% CI .21.03–4.88 in discovery set; HR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.07–2.93 in validation set). This module contained genes enriched in the biological process of the M phase. From this module, we further identified and validated 5 hub genes (CDK1, DLGAP5, MELK, NUSAP1, and RRM2), the expression levels of which were strongly associated with poor survival. Highly expressed MELK indicated poor survival in luminal A and luminal B breast cancer molecular subtypes. This gene was also found to be associated with tamoxifen resistance. Results indicated that a network-based approach may facilitate the discovery of biomarkers for the prognosis of ER+ breast cancer and may also be used as a basis for establishing personalized therapies. Nevertheless, before the application of this approach in clinical settings, in vivo and in vitro experiments and multi-center randomized controlled clinical trials are still needed.

Keywords: biomarker, breast cancer, gene expression profiling, systems biology, tamoxifen resistance

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ER+

estrogen receptor positive

- GS

gene significance

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor 2

- k.in

intramodular connectivity

- k.total

Network connectivity

- ME

module eigengene

- MS

module significance

- PCC

Pearson's correlation coefficient

- PR

progesterone receptor

- TOM

topologic overlap measure

- WGCNA

weighted gene co-expression network analysis

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies among women. This disease is characterized as a biologically heterogeneous group of neoplasms in reference to their clinical behavior and response to therapies. However, treatment-decision making relative to breast cancer remains largely dependent on conventional immunohistochemical markers and histopathological appearance that do not comprehensively consider tumor biology and latent response to treatment.

A few prognostic and predictive biomarkers are commonly used for breast cancer therapies. These biomarkers, such as several receptor proteins including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2), take tumor biology as a good indicator of breast cancer subtype.1 The presence of ER is the best indicator of response to anti-estrogen drugs, such as tamoxifen, and approximately 70% of breast cancer patients are ER positive.2 However, 30%–40% of women with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer fail to respond to tamoxifen effectively, and even for those who responded at the beginning of treatment would eventually develop acquired resistance.3 The underlying biological mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance remain incompletely understood, and a benchmark for personalizing ER+ breast cancer treatment remains lacking. Thus, a novel avenue should be established to predict prognosis and therapy response.

Given the large number of ER+ breast cancer patients that fail on tamoxifen, effective and reliable prognostic biomarkers that could be used to monitor tamoxifen efficacy should be identified. Identifying new targets to reverse tamoxifen resistance is also an important long-term goal for the development of highly effective therapeutic strategies.

Coexpression analysis has emerged as a powerful technique for multigene analysis. This approach is designed to uncover networks and genes associated with phenotypes of interest. A relatively novel coexpression approach is the weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA), a statistical technique that constructs gene sets (modules) from observed gene mRNA expression data with the use of unsupervised clustering and is thus independent of a priori defined gene sets or pathways. The basic concept of WGCNA analysis is the gene coexpression module, in which a group of genes was found to maintain a consistent expression relationship and may share a common biological regulation function.4

WGCNA has been successfully applied to cancer-related studies. This approach gas exposed the mRNA and microRNA expression network in prostate cancer,5 identified the ASPM gene as a novel molecular biomarker in glioblastoma,6 and identified coexpression networks related to proastrocytic differentiation and sprouty gignaling in glioma.7 WGCNA has been conducted by Wirapati et al.8 to analyze a breast cancer dataset consisting of 2833 patients. In this study, a type of supervised coexpression analysis was conducted against genes ESR1, AURKA, and ERBB2 to represent ER status, HER2 status, and proliferation, respectively. Moreover, Clarke et al.9 utilized WGCNA to identify 11 coregulated gene clusters across 2342 breast cancer patients from 13 microarray-based gene expression studies and explored the relationship between these transcriptional modules and clinicopathological variables (e.g., tumor size and grade), survival endpoints for breast cancer as a whole, and molecular subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2+, and basal-like).

In this study, we applied WGCNA to analyze a data set obtained from a transcriptome comprising 87 ER+ breast cancer patients. Compared with the coexpression analysis conducted by Wirapati8 and Clarke,9 our study solely focuses on ER+ breast cancer patients who have only received tamoxifen treatment. We identify gene modules and biomarkers (hub genes) for the prognosis of tamoxifen-treated ER+ breast cancer patients. Further, we validate our findings on an independent dataset of tamoxifen-treated samples obtained from a number of different institutions.

Results

Detection of gene coexpression modules

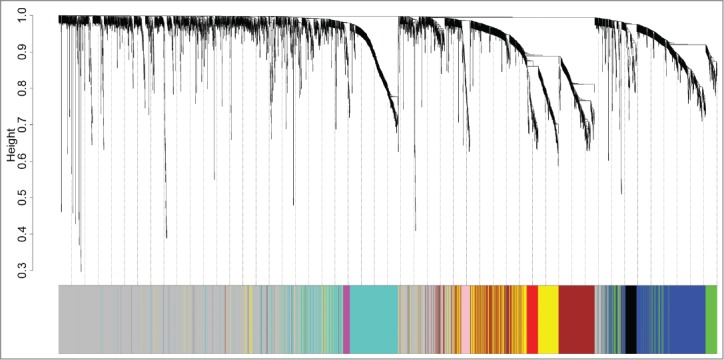

To investigate the functional organization of the ER+ breast cancer transcriptome and identify the gene coexpression modules, WGCNA methodology was employed to analyze the gene expression profiles derived from 87 ER+ breast cancer tumor tissues. Nine gene modules were identified (Fig. 1), and each was assigned with a unique color. Blue, black, green, magenta, turquoise, pink, brown, red, and yellow denoted 429, 64, 139, 37, 507, 46, 395, 79, and 358 genes, respectively. Module gray is the background color that represents the 1546 genes not assigned to any module. A complete list of the network metrics and the module membership for each gene is presented in Additional file 1.

Figure 1.

Identification of ER+ breast cancer specific modules using WGCNA. The clustering dendrogram of gene profilers from the data set GSE6532 with 87 ER+ breast cancer patients. Hierarchical cluster analysis dendrogram was used to detect coexpression clusters. Each short vertical line corresponds to a gene and the branches are expression modules of highly interconnected groups of genes with a color to indicate its module assignment. In total, 9 modules ranging from 37 to 507 genes in size were identified. The gray color suggests the 1546 genes that are outside of all the modules.

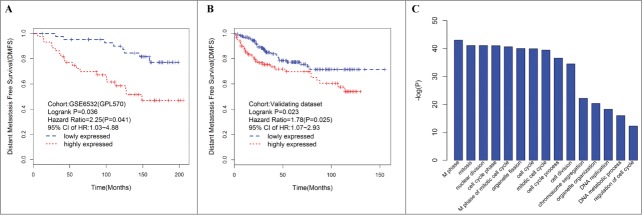

Of these modules, several were significantly associated with tumor grade and size. This result was as expected because tumor differences reflect different genetic backgrounds. We found a significant association of MEs of modules turquoise [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.03–4.88, p = 0.041) and magenta (HR = 2.50, 95% CI = 1.13–5.53 p = 0.024) with DFMS (Table 2). Further, the turquoise module was significantly associated with tumor grade (r = 0.60, P < 0 .001) and tumor size (r = 0.25, P = 0.020). Therefore, our subsequent analysis focuses on module turquoise. In the validating data set, we found a significant association of MEs of module turquoise (HR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.07–2.93, p = 0.025) with DFMS. Elevated expression of the turquoise module indicates poor outcome in ER+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen in the training (Fig. 2A) and validating datasets (Fig. 2B). For information on module turquoise, please refer to Additional file 2.

Table 2.

Association of expression modules with tumor grade, tumor size, and survival in discovery set

| Correlation with tumor grade |

Correlation with tumor size |

Association with DMFS (n = 87) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modules | Gene count | R | p-value | R | p-value | HR | p-value | 95% CI |

| Blue | 429 | −0.23 | 5.1 × 10–2 | 0.09 | 4.2 × 10–1 | 0.63 | 2.3 × 10–1 | 0.30–1.34 |

| Black | 64 | −0.35 | 3.0 × 10–2 | −0.21 | 5.2 × 10–2 | 0.81 | 5.7 × 10–1 | 0.38–1.70 |

| Green | 139 | −0.30 | 1.1 × 10–2 | −0.05 | 6.7 × 10–1 | 0.59 | 1.7 × 10–1 | 0.28–1.25 |

| Magenta | 37 | 0.31 | 8.0 × 10–3 | 0.15 | 1.5 × 10–1 | 2.50 | 2.4 × 10–2 | 1.13–5.53 |

| Turquoise | 507 | 0.63 | 5.4 × 10–9 | 0.26 | 2.6 × 10–2 | 2.25 | 4.1 × 10–2 | 1.03–4.88 |

| Pink | 46 | 0.18 | 1.5 ×10–1 | −0.01 | 9.2 × 10–1 | 1.30 | 4.9 × 10–1 | 0.62–2.75 |

| Brown | 395 | 0.05 | 7.1 × 10–1 | 0.18 | 9.1 × 10–2 | 0.57 | 1.5 × 10–1 | 0.27–1.22 |

| Red | 79 | 0.22 | 6.3 × 10–2 | 0.26 | 1.5 × 10–2 | 0.62 | 2.2 × 10–1 | 0.29–1.33 |

| Yellow | 358 | 0.30 | 1.1 × 10–2 | 0.28 | 8.0 × 10–3 | 1.12 | 7.6 × 10–1 | 0.53–2.37 |

CI, confidence interval. Distant metastasis free survival (DMFS).

Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis after grouped the breast cancer patients by the median of module eigengenes level.

Figure 2.

Elevated expression of the turquoise ME, a group of coexpressed genes indicates poor outcome in ER+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Kaplan–Meier survival plots for RFS in the training (A) and validating (B) datasets. Increased expression (red) of this coexpressed group is associated with poor RFS. (C) GO enrichment analysis for the 507 genes comprising the turquoise module identifies multiple processes related to cell proliferation. The original significance outputted from DAVID for GO biological processes were transformed in to “–log (P-value)” for plotting.

Biological insights from module turquoise

To elucidate the potential biological mechanisms of module turquoise, we performed GO biological enrichment analysis with DAVID and found significant GO biological terms enriched in module turquoise (Fig. 2C, Table S1). The most significant biological GO terms for module turquoise are “M phase” (raw p value = 9.60 × 10−44 Bonferroni-adjusted p value = 1.82 × 10−40). We also examined the module genes of turquoise for correlation between gene significance (GS) and gene connectivity. Interestingly, the survival-related GS was significantly correlated with gene connectivity (R = 0.36, p = 2.22 × 10−16) (Fig. S1), thereby suggesting that the genes with more significant survival association tended to be highly connected genes and are thus the most important genes in the module.

Definition and validation of survival-related hub genes

Hub genes are more likely to serve a key function in a highly connected network. For the 507 genes in module turquoise, we further defined 6 as hub genes (CDK1, DLGAP5, NUSAP1, RRM2, MELK, and DEPDC1), which were highly connected with the module turquoise and associated with DMFS on the basis of the following criteria; (i) the value of intramodular connectivity (k.in, described in the method section) belongs to the first 40 ones of module turquoise and (ii) a gene significance (GS) higher than 2. Furthermore, the gene expressions of 5 of the 6 hub genes (CDK1, DLGAP5, NUSAP1, RRM2, and MELK) were significantly associated with survival (DMFS and RFS) and were replicated in the validation sets (Table 3). To determine whether any of the 5 identified hub genes was associated with clinicopathological information, we calculated the Pearson's correlation coefficients (PCC) between gene expression and tumor size and grade (Table S2). We observed that all 5 hub genes yielded significantly positive PCCs with tumor grade in both the training and validating data sets. Patients with a higher gene signature have a higher risk of death than those with a lower gene signature.

Table 3.

Association relationship between hub genes with survival

| Training data set (n = 87) |

Validating dataset (n = 449) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFS |

DMFS |

RFS |

|||||||

| Gene | HR | p-value | 95% CI | HR | p-value | 95% CI | HR | p-value | 95% CI |

| CDK1 | 2.92 | 8.5 × 10–3 | 1.31–6.49 | 3.07 | 3.0 × 10–5 | 1.81–5.21 | 2.13 | 1.3 × 10–5 | 1.52–3.00 |

| DEPDC1 | 3.34 | 4.1 × 10–3 | 1.47–7.62 | 0.93 | 7.9 × 10–1 | 0.54–1.58 | 0.98 | 8.9 V 10–1 | 0.71–1.35 |

| DLGAP5 | 2.86 | 9.9 × 10–3 | 1.29–6.35 | 1.98 | 7.8 × 10–3 | 1.20–3.26 | 1.77 | 8.2 × 10–4 | 1.27–2.47 |

| MELK | 3.52 | 2.4 × 10–3 | 1.54–8.05 | 2.55 | 2.9 × 10–4 | 1.54–4.24 | 1.97 | 8.9 × 10–5 | 1.40–2.77 |

| NUSAP1 | 2.97 | 7.6 × 10–3 | 1.34–6.62 | 2.35 | 9.2 × 10–4 | 1.42–3.89 | 1.43 | 3.6 × 10–2 | 1.02–1.99 |

| RRM2 | 2.86 | 9.8 × 10–3 | 1.29–6.36 | 1.85 | 1.6 × 10–2 | 1.12–3.06 | 2.04 | 3.9 × 10–5 | 1.45–2.86 |

Recurrence free survival (RFS), Distant metastasis free survival (DMFS). Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis after grouped the breast cancer patients by the median of gene level.

Identification of hub genes with significant breast cancer subtype-specific survival associations

In addition to survival analysis in breast cancer as a whole, we also determined whether significant associations could be found between the 5 hub genes (CDK1, DLGAP5, NUSAP1, RRM2, and MELK) and the molecular subtypes. We calculated HRs and accompanying P-values to highlight single gene markers for the luminal A and luminal B subtypes (Table 4). MELK is particularly interesting because its increased expression is indicative of poor prognosis within the luminal A (HR = 2.7 for DMFS, HR = 2.04 for RFS) and luminal B subtypes (HR = 2.13 for DMFS, HR = 1.91 for RFS) in the validating dataset. The HRs for MELK in the training data set are 1.88 and 2.60 for the luminal A and luminal B subtypes, respectively. The corresponding P-values of HRs failed to reach statistical significance, which may be attributed to the small sample size.

Table 4.

Association relationship between hub genes with survival within breast cancer molecular subtypes

| Training data set (n = 87) |

Validating dataset (n = 449) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMFS |

DMFS |

RFS |

||||||||||

| luminal A |

luminal B |

luminal A |

luminal B |

luminal A |

Luminal B |

|||||||

| Gene | HR | p-value | HR | p-value | HR | p-value | HR | p-value | HR | p-value | HR | p-value |

| CDK1 | 0.90 | 8.6 × 10–1 | 1.83 | 2.8 × 10–1 | 1.50 | 3.6 × 10–1 | 1.84 | 5.9 × 10–2 | 1.52 | 1.0 × 10–1 | 1.76 | 1.6 × 10–2 |

| DLGAP5 | 1.74 | 3.5 × 10–1 | 2.80 | 8.2 × 10–2 | 1.44 | 4.0 × 10–1 | 0.91 | 7.8 × 10–1 | 1.61 | 6.7 × 10–2 | 1.08 | 7.3 × 10–1 |

| MELK | 1.88 | 2.8 × 10–1 | 2.60 | 9.0 × 10–2 | 2.70 | 2.8 × 10–2 | 2.04 | 2.8 × 10–2 | 2.13 | 5.4 × 10–3 | 1.91 | 6.4 × 10–3 |

| NUSAP1 | 1.25 | 7.0 × 10–1 | 2.88 | 7.5 × 10–2 | 2.23 | 7.0 × 10–2 | 1.12 | 7.2 × 10–1 | 1.50 | 1.2 × 10–1 | 0.92 | 7.0 × 10–1 |

| RRM2 | 1.09 | 8.9 × 10–1 | 1.16 | 7.9 × 10–2 | 1.41 | 4.4 × 10–1 | 1.08 | 8.1 × 10–1 | 1.91 | 1.4 × 10–2 | 1.22 | 3.8 × 10–2 |

Recurrence free survival (RFS), Distant metastasis free survival (DMFS). Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis after grouped the breast cancer patients by the median of gene level.

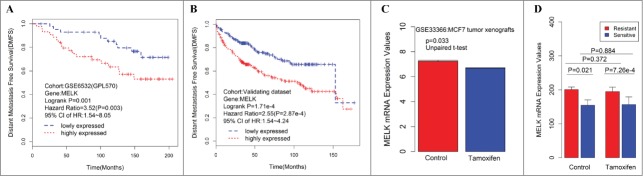

Identification of hub genes that may participate in tamoxifen resistance

From the above results, we can infer that high expression of hub genes confers poor survival in ER+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen, such that these hub genes may serve a potential function in tamoxifen resistance. To validate this hypothesis, 2 datasets, GSE3336610 and GSE26459,11 were downloaded from GEO and analyzed. In vivo data showed that MELK expression was downregulated in MCF-7 tumor xenograft treatment with tamoxifen compared with control (p = 0.033, Fig. 3C), which indicates that tamoxifen could decrease MELK expression in ER+ breast cancer cells. In vitro experiment results showed that MELK was overexpressed in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 subclones compared with sensitive controls, regardless of whether patients were treated with tamoxifen (Fig. 3D, P = 7.26 × 10−44 and 0.021, respectively), which indicates that MELK may potentially affect tamoxifen resistance. Thus, tamoxifen could downregulate MELK expression in vivo (Fig. 3C, P = 0.033). Similar trends are emerging in vitro (Fig. 3D, P = 0.884). However, these findings are not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Consistent associations between RFS and the MELK genes are observed across the training data set and validating data set. Kaplan–Meier survival plot for RFS for MELK indicates increased expression (red) of this gene indicates poor prognosis in the training dataset (A) and validating data set (B). Breast cancer patients grouped by the median of gene expression level, significances were assessed by logrank test. (D) Log2 transformed mRNA expression values of MELK in MCF-7 tumor xenografts treated with either tamoxifen or control. P values were calculated by independent 2-tailed t test. Error bars represent mean ± SD. (E) mRNA expression values of MELK in tamoxifen resistant/sensitive MCF-7 subclones treated with tamoxifen or control. P values were calculated by unpaired 2-tailed t test. Error bars represent mean ± SD.

Discussion

In this study, we applied a system biology approach called WGCNA to examine gene coexpression patterns in ER+ breast cancer tumor tissues of patients treated with tamoxifen. We identified a gene module enriched with cell proliferation-related genes. Expression signatures of the module were significantly correlated with tumor grade and size, as well as with survival. Further, 5 hub genes proved to be biomarkers for the prognosis of ER+ breast cancer. Among these genes, increased MELK expression indicates poor survival in the luminal A and luminal B molecular subtypes, which may also be associated with tamoxifen resistance.

Therapy for ER+ breast cancer, which represents more than 70% of breast tumors, is based on anti-hormonal compounds, such as the commonly used anti-estrogen tamoxifen12. Tamoxifen improves overall survival and reduces the risk for developing breast cancer for adjuvant therapy of ER+ breast cancer.13 However, approximately 30% of the patients who received adjuvant tamoxifen would eventually experience relapse and may finally die as a result of the disease.14 Several groups have performed gene-expression analysis by combining endocrine therapy with agents that could modulate these mechanisms to identify ER-regulated genes that are affected by tamoxifen in breast cancer cells. 15,16 The pressing clinical need has motivated several investigators to develop gene signatures that predict clinical responses to tamoxifen. 17-19 For instance, Retinoic acid receptor α, CD44, and delta EF1 have been reportedly involved in the development of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. 20-23 Likewise, Cyclin D1, Acid ceramidase 1 and p53 accumulation, as well as CCNA2 and CCNB1, have been reported to have the capability to predict outcomes in ER+ breast cancer treated with adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy. 18,24-26 Sgroi et al. reported that the breast-cancer index (BCI) assay was a significant prognostic test for the risk of both early and late distant recurrence that could help to identify patients at high risk for late distant recurrence who might benefit from extended endocrine or other therapy.19

Compared with former studies, ours is the only network-based meta-analysis with full use of publically available records of ER+ breast cancer patient treated with tamoxifen. We adopted a system biology approach by focusing on a handful of modules rather than tens of thousands of individual genes. The benefit of this network-based approach is its capability to reveal the complex biological mechanisms responsible for the phenotype of interest. We observed significant association of the cell proliferation-related gene module with survival, indicating that the molecular signatures may predict the survival of ER+ breast cancer patients. This finding further reinforces the important function of the cell proliferation-related gene network in determining disease progression and patient survival.

Further, our analysis identified 5 hub genes (CDK1, DLGAP5, NUSAP1, RRM2, and MELK) from the network, thus demonstrating the significant association with survival in the training and validating data sets. Among these genes, increased expression of MELK was associated with the poor survival of patients within the luminal A and luminal B subtypes. Moreover, such expression may serve a critical function in tamoxifen resistance. MELK was identified as a key regulator of the proliferation of malignant brain tumors and aggressiveness in human astrocytomas 27,28 and was associated with breast cancer 29,30 and lung cancer prognosis 31. NOTCH3 gene amplification is known to be an important contributor to the progression of many ovarian and breast cancers. The mitotic apparatus organizing protein DLGAP5 has been reported to be a critical target of NOTCH3 signaling.32 Integrating meta-analysis of the microarray data verified CDK1 as potential biomarker to discriminate between estrogen receptor positive patients of high- and low-risk of disease recurrence.33 Further, CDK1 inhibition may be a potential therapy for MYC-dependent breast cancer.34 NUSAP1 and RRM2 were significantly upregulated in mice and human ductal carcinoma in situ samples, suggesting that they may be an early molecular marker for breast cancer.35 RRM2 was also identified as a prognostic marker in breast cancer associated with poor survival and tamoxifen resistance through pathway-centric integrative analysis.36

Although considerable information on ER and breast cancer has been provided since the availability of tamoxifen in clinical practice, effort should be taken to elucidate favorable therapeutic outcomes. More specific research outcomes will require translational research that may yield safer and more efficient treatment for breast cancer patients.

Our study has some limitations. In particular, some established predictors of breast cancer prognosis, such as protein expression of HER2 and PR, were not included because this information is unavailable. Further, although WGCNA is a powerful bioinformatics method, consistently co-expressed genes may have interdependent mechanistic relationships that are not yet appreciated. This condition may result in the co-identification of these genes in association studies. Thus, the significance and robustness of the network and hub genes in prognostic classification requires further confirmation, ideally with large prospective patient cohorts included in adjuvant trials.

In summary, our study has used the system biology-based WGCNA approach to reveal a gene network that apparently serves an important function in the regulation of ER+ breast cancer treated with tamoxifen and provides potential gene markers (CDK1, DLGAP5, NUSAP1, RRM2, and MELK) for predicting prognosis. In addition, the proposed approach suggests the relevance of MELK in the development of tamoxifen resistance. Furthermore, findings could provide guidance for personalized therapies. Nevertheless, multi-center randomized controlled clinical trials and in vivo/in vitro experiments are still required to evaluate the possible application of the molecular signatures for survival prediction and to characterize the key genes functionally for the application of this approach in clinical settings.

Methods

Publically available data sets

The training dataset used for network generation consisted of 87 ER+ breast cancer samples, all of whom had only received tamoxifen treatment. The data set was downloaded from GEO database with accession number GSE6532.37 For data processing methods, please refer to Loi et al.37 This dataset contains samples from the Guys Hospital (GUYT) and has been hybridized using Affymetrix U133 PLUS 2 Genechips™. All samples were required to be ER+ by ligand binding assay and have been prescribed tamoxifen mono therapy for 5 year post diagnosis as adjuvant therapy.

The independent validation set with 475 samples was used to validate the association between gene modules/hub genes and survival of ER+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Samples from 3 studies were downloaded from GEO with the accession numbers GSE6532,38 GSE3494,39 and GSE2990.40 All samples were hybridized using Affymetrix U133 A Gene-chips™ according to standard Affymetrix protocols. There are 327, 251, and 189 samples in GSE6532, GSE3494 and GSE2990, respectively, and 200, 213, and 62 ER+ breast cancer patients among them were utilized in our analysis.

For all the study subjects in this training and validating data set, the cut-off value for patient classification as positive or negative for ER was 10 fmol per mg protein. Raw gene expression values were processed with robust multiarray average algorithms. The primary endpoint for the training dataset was the first distant metastatic event (distant metastasis free survival, DMFS), whereas DMFS and recurrence free survival (RFS) were considered for the validating data set. Demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the datasets

| Characteristics | Training Dataset (n = 87) | Validating Dataset (n = 449) |

|---|---|---|

| Age: mean (sd) | 62.8 (8.6) | 62.1 (12.1) |

| Grade (%) | ||

| I | 17 (19.5) | 116 (25.8) |

| II | 37 (42.5) | 230 (51.2) |

| III | 16 (18.4) | 64 (14.3) |

| Unknown | 17 (19.5) | 39 (8.7) |

| Size: mean (sd) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.2) |

| Lymph node status(%) | 58 (66.7) | 143 (31.8) |

| Type (%) | ||

| Basal-like | 1 (1.1) | 11 (2.4) |

| Her2+ | 3 (3.5) | 15 (3.3) |

| luminal A | 44 (50.6) | 267 (59.5) |

| luminal B | 39 (44.8) | 156 (34.7) |

| RFS | ||

| Time mean (sd) | – | 52.8 (41.7) |

| Event (%) | – | 150 (33.4) |

| DMFS | ||

| Time mean (sd) | 121.6 (56.1) | 48.84 (39.0) |

| Event (%) | 28 (32.2) | 62 (13.8) |

Two tamoxifen-related datasets were downloaded. GSE333-6610 contains expression data from MCF-7 tumor xenografts treated with tamoxifen or nothing for 28 d, with each group having 2 biological replicates. GSE26459 11 contains expression data from subcloned MCF-7 cell lines that were either naturally resistant or highly sensitive to tamoxifen, with each group having 3 biological replicates.

Classification of breast cancer subtypes

Breast cancers were divided into luminal A, luminal B, HER2+, and basal-like subtypes using the pam5041 classifiers via the ‘genefu’ R package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/genefu.html). For subsequent analyses, samples were included within subtypes on the basis of classification by at least one the above classifiers. The sample sizes for each subtype in the training and validating data sets are shown in Table 1.

Coexpression module detection

Before module detection, probesets without known gene symbols were excluded, and probe-level expression profiles for all the datasets were converted to gene-level expressions by employing a probe merging technique with the collapseRows function. 42 We selected the top 5000 varying genes after sorting their standard deviations in an ascending order across the 87 samples. The WGCNA was restricted to 3600 of the most connected genes (based on k.total, as described below) from the 5000 genes used for the R ‘wgcna’ package. 43 First, we compute a correlation matrix for each pair of genes and then obtain an adjacency matrix by raising the matrix to a soft threshold power to avoid the selection of an arbitrary cut-off. The network connectivity (k.total) of the gene was defined as the sum of its adjacency with all the other genes for network generation. Meanwhile, the intramodular connectivity (k.in) was calculated as the summation of adjacency performed over all genes in a particular network. The decision value of the threshold power was determined on the basis of the scalefree topology criterion, which aims to mimic a network structure commonly found in nature.

In this study, we selected a threshold of 6. Coexpression dissimilarity for each gene pair from the adjacency matrix is determined via a network distance measure known as the topological overlap measure (TOM). Modules were defined as branches of the hierarchical cluster tree generated using the TOM dissimilarity. The hybrid dynamic tree cutting method was used to cut branches using a minimum module size of 30 and a maximum height of 0.95. The module eigengenes (MEs) were produced by retaining the first principal component following principal components analysis of the processed expression data for each group of coexpressed probesets across the 87 samples. Module membership assignment (kME) was determined as the Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC) between gene expression values and the module eigengene.

Module and clinical trait association analysis

Survival analysis was performed with the ‘survival’ R package (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html). The HR and corresponding 95% CI were determined via a Cox regression model, and survival curves were plotted from Kaplan–Meier estimates. For multigene (module) associations, each ME was dichotomized to high and low expression around its median value.

Signal gene-based survival analysis and hub genes

In the training data set, a univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to regress patient DMFS on the individual gene expression levels, which were dichotomized around the median expression of such gene. The survival-based GS was defined as minus log 10 of the univariate Cox-regression p-values. Hub genes were those that show high network connectivity (k.in), which measured the connect strength (co-expressed) of a given gene with other genes in a given module. On the basis of the GS and k.in, we identify hub genes that showed high correlation with clinical traits, as well as high connectivity in the trait-related modules.

As regards the survival analysis in the validating dataset, allowing for interstudy variation, we dichotomize each gene around its median expression value within each individual study and then combine all studies to conduct a meta-survival analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression model to regress patient DMFS or RFS.

Functional annotation of the module

To extract further biological insight from genes belonging to modules associated with survival of ER+ breast cancer patients, we searched for overrepresentation in gene ontology (GO) categories. Functional annotation of the modules was performed on the basis of gene composition. To test a module for enrichment in the genes with particular GO biological process compared with the background list of all the genes on the array, enrichment scores (Fisher exact test p value) for all GO terms in the specified ontologies (biological processes) were calculated with DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) 44. Multiple testing was corrected using the Bonferroni method.

Author Contributions

Rong Liu designed the study, wrote the paper, and analyzed the data; Cheng-Xian Guo revised the whole paper; and Hong-Hao Zhou contributed to the study design and final approval of the version to be published.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the National Scientific Foundation of China (81301924), Scientific Foundation of Hunan (14JJ7016) and science and technology plan of Changsha (k1403065-31).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Zhang X, Claerhout S, Prat A, Dobrolecki LE, Petrovic I, Lai Q, Landis MD, Wiechmann L, Schiff R, Giuliano M, et al. A renewable tissue resource of phenotypically stable, biologically and ethnically diverse, patient-derived human breast cancer xenograft models. Cancer Res 2013; 73:4885-97; PMID:23737486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer J Int Du Cancer 2010; 127:2893-917; PMID:21351269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vendrell JA, Ghayad S, Ben-Larbi S, Dumontet C, Mechti N, Cohen PA. A20/TNFAIP3, a new estrogen-regulated gene that confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2007; 26:4656-67; PMID:17297453; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1210269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stuart JM, Segal E, Koller D, Kim SK. A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science 2003; 302:249-55; PMID:12934013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1087447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang L, Tang H, Thayanithy V, Subramanian S, Oberg AL, Cunningham JM, Cerhan JR, Steer CJ, Thibodeau SN. Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2009; 69:9490-7; PMID:19996289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horvath S, Zhang B, Carlson M, Lu KV, Zhu S, Felciano RM, Laurance MF, Zhao W, Qi S, Chen Z, et al. Analysis of oncogenic signaling networks in glioblastoma identifies ASPM as a molecular target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:17402-7; PMID:17090670; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0608396103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ivliev AE, t Hoen PA, Sergeeva MG. Coexpression network analysis identifies transcriptional modules related to proastrocytic differentiation and sprouty signaling in glioma. Cancer Res 2010; 70:10060-70; PMID:21159630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wirapati P, Sotiriou C, Kunkel S, Farmer P, Pradervand S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Ignatiadis M, Sengstag T, Schutz F, et al. Meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in breast cancer: toward a unified understanding of breast cancer subtyping and prognosis signatures. Breast Cancer Res 2008; 10:28; PMID:18662380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarke C, Madden SF, Doolan P, Aherne ST, Joyce H, O'Driscoll L, Gallagher WM, Hennessy BT, Moriarty M, Crown J, et al. Correlating transcriptional networks to breast cancer survival: a large-scale coexpression analysis. Carcinogenesis 2013; 34:2300-8; PMID:23740839; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/carcin/bgt208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nishida Y, Yoshioka M, St-Amand J. Regulation of hypothalamic gene expression by glucocorticoid: implications for energy homeostasis. Physiol Genomics 2006; 25:96-104; PMID:16368873; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00232.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonzalez-Malerva L, Park J, Zou L, Hu Y, Moradpour Z, Pearlberg J, Sawyer J, Stevens H, Harlow E, LaBaer J. High-throughput ectopic expression screen for tamoxifen resistance identifies an atypical kinase that blocks autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2058-63; PMID:21233418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1018157108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castellano I, Chiusa L, Vandone AM, Beatrice S, Goia M, Donadio M, Arisio R, Muscara F, Durando A, Viale G, et al. A simple and reproducible prognostic index in luminal ER-positive breast cancers. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ESMO 2013; 24:2292-7; PMID:23709174; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdt183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. (EBCTCG). EBCTCG . Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005; 365:1687-717; PMID:15894097; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90:1371-88; PMID:9747868; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frasor J, Chang EC, Komm B, Lin CY, Vega VB, Liu ET, Miller LD, Smeds J, Bergh J, Katzenellenbogen BS. Gene expression preferentially regulated by tamoxifen in breast cancer cells and correlations with clinical outcome. Cancer Res 2006; 66:7334-40; PMID:16849584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan M, Yan PS, Hartman-Frey C, Chen L, Paik H, Oyer SL, Salisbury JD, Cheng AS, Li L, Abbosh PH, et al. Diverse gene expression and DNA methylation profiles correlate with differential adaptation of breast cancer cells to the antiestrogens tamoxifen and fulvestrant. Cancer Res 2006; 66:11954-66; PMID:17178894; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chanrion M, Negre V, Fontaine H, Salvetat N, Bibeau F, Mac Grogan G, Mauriac L, Katsaros D, Molina F, Theillet C, et al. A gene expression signature that can predict the recurrence of tamoxifen-treated primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:1744-52; PMID:18347175; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jansen MP, Foekens JA, van Staveren IL, Dirkzwager-Kiel MM, Ritstier K, Look MP, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Sieuwerts AM, Portengen H, Dorssers LC, et al. Molecular classification of tamoxifen-resistant breast carcinomas by gene expression profiling. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:732-40; PMID:15681518; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sgroi DC, Sestak I, Cuzick J, Zhang Y, Schnabel CA, Schroeder B, Erlander MG, Dunbier A, Sidhu K, Lopez-Knowles E, et al. Prediction of late distant recurrence in patients with oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer: a prospective comparison of the breast-cancer index (BCI) assay, 21-gene recurrence score, and IHC4 in the TransATAC study population. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14:1067-76; PMID:24035531; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70387-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo S, Li Y, Tong Q, Gu F, Zhu T, Fu L, Yang S. deltaEF1 down-regulates ER-alpha expression and confers tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. PloS one 2012; 7:e52380; PMID:23285017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0052380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johansson HJ, Sanchez BC, Mundt F, Forshed J, Kovacs A, Panizza E, Hultin-Rosenberg L, Lundgren B, Martens U, Mathe G, et al. Retinoic acid receptor alpha is associated with tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Nat Commun 2013; 4:2175; PMID:23868472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao T, Han Y, Yu L, Ao S, Li Z, Ji J. CCNA2 is a prognostic biomarker for ER+ breast cancer and tamoxifen resistance. PloS One 2014; 9:e91771; PMID:24622579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0091771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ding K, Li W, Zou Z, Zou X, Wang C. CCNB1 is a prognostic biomarker for ER+ breast cancer. Med Hypotheses 2014; 83:359-64; PMID:25044212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma XJ, Wang Z, Ryan PD, Isakoff SJ, Barmettler A, Fuller A, Muir B, Mohapatra G, Salunga R, Tuggle JT, et al. A two-gene expression ratio predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Cancer Cell 2004; 5:607-16; PMID:15193263; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, Baehner FL, Walker MG, Watson D, Park T, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. New Engl J Med 2004; 351:2817-26; PMID:15591335; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa041588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu XL, Chen SZ, Chen W, Zheng WH, Xia XH, Yang HJ, Li B, Mao WM. The impact of cyclin D1 overexpression on the prognosis of ER-positive breast cancers: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 139:329-39; PMID:23670132; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-013-2563-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marie SK, Okamoto OK, Uno M, Hasegawa AP, Oba-Shinjo SM, Cohen T, Camargo AA, Kosoy A, Carlotti CG, Jr, Toledo S, et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase transcript abundance correlates with malignancy grade in human astrocytomas. Int J Cancer J Int Du Cancer 2008; 122:807-15; PMID:17960622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.23189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakano I, Masterman-Smith M, Saigusa K, Paucar AA, Horvath S, Shoemaker L, Watanabe M, Negro A, Bajpai R, Howes A, et al. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase is a key regulator of the proliferation of malignant brain tumors, including brain tumor stem cells. J Neurosci Res 2008; 86:48-60; PMID:17722061; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jnr.21471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pickard MR, Green AR, Ellis IO, Caldas C, Hedge VL, Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Dysregulated expression of Fau and MELK is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2009; 11:11; PMID:19671159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin ML, Park JH, Nishidate T, Nakamura Y, Katagiri T. Involvement of maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) in mammary carcinogenesis through interaction with Bcl-G, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family. Breast Cancer Res 2007; 9:R17; PMID:17280616; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Y, Tang H, Sun Z, Bungum AO, Edell ES, Lingle WL, Stoddard SM, Zhang M, Jen J, Yang P, et al. Network-based approach identified cell cycle genes as predictor of overall survival in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Lung Cancer 2013; 80:91-8; PMID:23357462; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen X, Thiaville MM, Chen L, Stoeck A, Xuan J, Gao M, Shih Ie M, Wang TL. Defining NOTCH3 target genes in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 2012; 72:2294-303; PMID:22396495; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pavlou MP, Dimitromanolakis A, Martinez-Morillo E, Smid M, Foekens JA, Diamandis EP. Integrating meta-analysis of microarray data and targeted proteomics for biomarker identification: application in breast cancer. J Proteome Res 2014; 13:2897-909; PMID:24799281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/pr500352e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kang J, Sergio CM, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) but not CDK4/6 or CDK2 is selectively lethal to MYC-dependent human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2014; 14:1471-2407; PMID:24444383; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-14-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kretschmer C, Sterner-Kock A, Siedentopf F, Schoenegg W, Schlag PM, Kemmner W. Identification of early molecular markers for breast cancer. Mol Cancer 2011; 10:15; PMID:21314937; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-4598-10-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Putluri N, Maity S, Kommangani R, Creighton CJ, Putluri V, Chen F, Nanda S, Bhowmik SK, Terunuma A, Dorsey T, et al. Pathway-centric integrative analysis identifies RRM2 as a prognostic marker in breast cancer associated with poor survival and tamoxifen resistance. Neoplasia 2014; 16:390-402; PMID:25016594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neo.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Lallemand F, Tutt AM, Gillet C, Ellis P, Harris A, Bergh J, Foekens JA, et al. Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:1239-46; PMID:17401012; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, Wirapati P, Lallemand F, Tutt AM, Gillet C, Ellis P, Ryder K, Reid JF, et al. Predicting prognosis using molecular profiling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. BMC Genomics 2008; 9:1471-2164; PMID:18498629; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-9-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller LD, Smeds J, George J, Vega VB, Vergara L, Ploner A, Pawitan Y, Hall P, Klaar S, Liu ET, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:13550-5; PMID:16141321; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0506230102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sotiriou C, Wirapati P, Loi S, Harris A, Fox S, Smeds J, Nordgren H, Farmer P, Praz V, Haibe-Kains B, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98:262-72; PMID:16478745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/djj052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, Leung S, Voduc D, Vickery T, Davies S, Fauron C, He X, Hu Z, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:1160-7; PMID:19204204; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller J, Cai C, Langfelder P, Geschwind D, Kurian S, Salomon D, Horvath S. Strategies for aggregating gene expression data: the collapseRows R function. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:322; PMID:21816037; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2105-12-322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang B, Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 2005; 4:Article17; PMID:16646834; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2202/1544-6115.1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dennis G, Sherman B, Hosack D, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki R. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol 2003; 4:P3; PMID:12734009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.