Abstract

Hemorrhage and coagulopathy remain major drivers of early preventable mortality in military and civilian trauma. The development of trauma-induced coagulopathy and hyperfibrinolysis is associated with poor outcomes. Interest in the use of tranexamic acid (TXA) in hemorrhaging patients as an antifibrinolytic agent has grown recently. Additionally, several reports describe immunomodulatory effects of TXA that may confer benefit independent of its antifibrinolytic actions. A large trial demonstrated a mortality benefit for early TXA administration in patients at risk for hemorrhage; however, questions remain about the applicability in developed trauma systems and the mechanism by which TXA reduces mortality. We describe here the rationale, design, and challenges of the Study of Tranexamic Acid during Air Medical Prehospital transport (STAAMP) trial. The primary objective is to determine the effect of prehospital TXA infusion during air medical transport on 30-day mortality in patients at risk of traumatic hemorrhage. This study is a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. The trial will enroll trauma patients with hypotension and tachycardia from 4 level I trauma center air medical trans- port programs. It includes a 2-phase intervention, with a prehospital and in-hospital phase to investigate multiple dosing regimens. The trial will also explore the effects of TXA on the coagulation and inflammatory response following injury. The trial will be conducted under exception for informed consent for emergency research and thus required an investigational new drug approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as well as a community consultation process. It was designed to address several existing knowledge gaps and research priorities regarding TXA use in trauma.

Keywords: trauma, prehospital, tranexamic acid, clinical trial, hemorrhage, coagulopathy

Introduction and Rational for Tranexamic Acid in Trauma

Hemorrhage and coagulopathy remain major drivers of preventable early death following injury.1–4 Up to 80% of deaths in the first hour and more than 50% of deaths in the prehospital setting are due to hemorrhage.1 It has become increasingly recognized that trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) occurs early and carries significant sequela. Once thought to be an iatrogenic phenomenon, several studies have now shown that coagulation abnormalities are evident at the scene of injury and upon admission to the trauma center.2,5–7 Patients who develop TIC have been consistently shown to have worse outcomes.2,5,8,9 TIC involves a cascade of events related to tissue injury and hemorrhage that results in systemic activation of protein C, hyperfibrinolysis, endothelial and platelet dysfunction, complement activation, and release of inflammatory mediators.10–15 Hyperfibrinolysis has been shown to be a primary component in the development of TIC.16

Patients with hyperfibrinolysis are at risk for significantly worse outcomes. Authors have reported mortality rates between 52 and 88% for patients with hyperfibrinolysis on measures of viscoelastic coagulation such as thromboelastography (TEG) at admission.16–20 Additionally, these patients are at higher risk for massive transfusion, multiple organ failure, longer intensive care unit stay, and overall length of stay.16,18,20–22 More recently, it has been recognized that lower levels of fibrinolytic activation are associated with poor outcomes.21 Raza et al. found only 5% of patients had hyperfibrinolysis defined on TEG; however, 57% had evidence of moderate fibrinolytic activity defined as plasmin–antiplasmin complex levels twice normal.22

TXA is a synthetic derivative of lysine that binds competitively to plasminogen to prevent conversion to active plasmin, which degrades fibrin. Investigators have hypothesized that the antifibrinolytic properties of TXA would reduce bleeding and need for blood transfusion with resultant reductions in mortality and morbidity. There is evidence that TXA may have effects outside of antifibrinolysis. Plasmin has proinflammatory effects though activation of inflammatory cells, platelets, and endothelial cells, and plays a role in innate immune signaling.23,24 Plasmin induces chemotaxis of monocytes and dendritic cells and promotes the release of proinflammatory cytokines.24,25 Thus, TXA may exert a beneficial action through inhibition of plasmin and attenuation of proinflammatory, ischemia–reperfusion, and complement activation responses.11,26–28

Civilian and Military Studies of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma

The CRASH-2 trial randomized over 20,000 patients in 40 countries to receive TXA or placebo. Tranexamic was given as a 1-g bolus over 10 minutes followed by 1 g over 8 hours, a dose known to inhibit fibrinolysis. The authors reported a significant absolute risk reduction in 28-day mortality of 1.5%, and 0.8% in death from hemorrhage among those receiving TXA.29 There was no difference in vascular occlusive events reported. An exploratory analysis demonstrated that the greatest reduction in death from hemorrhage occurred if TXA was given within 1 hour of injury and this benefit persisted until 3 hours, after which it appear mortality increased in the TXA group.30 These encouraging results spurred interest in TXA as a therapy for the hemorrhaging trauma patient.

Despite this, several concerns have been raised surrounding the CRASH-2 trial.31,32 Only half of patients received red cell transfusions and no data were collected on injury or shock severity, coagulopathy or fibrinolysis, or other blood products administered. There was no evaluation of the mechanism of these improved outcomes. Importantly, there was no difference in transfusion requirements between groups, suggesting the benefits seen may be due to effects outside the antifibrinolytic properties of TXA. Adverse events were not systematically collected. Finally, the trial took place almost exclusively in the developing world, with only 1.4% of patients treated in hospitals with developed trauma systems. Although this trial has resulted in implementation of TXA in many trauma centers around the world, there remain concerns about the applicability to modern developed trauma systems in the United States and Europe.

Military application of TXA has been promising as well. The MATTERs study of nearly 900 combat casualties was a retrospective cohort that demonstrated a 6.5% lower unadjusted mortality despite higher injury severity, and independent association with lower adjusted mortality and coagulopathy in those receiving TXA.33 These findings were confirmed in the MAT-TERs II study in over 1,000 combat casualties.34 These studies also demonstrated the greatest benefit of TXA in massive transfusion patients. The retrospective nature of these studies made it impossible to investigate underlying mechanisms driving these benefits. Transfusion requirements were higher in the TXA group; however, the higher injury severity confounds the finding. A higher rate of venous thromboembolic events was also found in the TXA group, raising safety concerns.

Although the reduction in mortality persists in both civilian and military studies, the discrepancies between MATTERs and CRASH-2 demand further analysis regarding safety, mechanism, dosage, and timing of TXA. There is little evidence supporting the use of TXA in the civilian prehospital setting.35 The benefits of TXA given within the first hour from injury have stimulated interest in potential prehospital administration, bolstered by success of prehospital administration in military studies.30,36 Vu and colleagues report the first administration of civilian prehospital TXA; however, there was no follow-up for patient outcomes or adverse events.37

Care must be taken prior to widespread adoption of TXA in the civilian prehospital setting. The safety profile remains uncertain. In light of concerns over increased venous thromboembolism events in the MAT-TERs trial and the limitations of the adverse event reporting in the CRASH-2 trial, optimal safety has not been established.29,32,33 There are further concerns related to aeromedical evacuation times that have not been adequately studied to justify widespread integration.38 Development of rigorous protocols for patients at risk of hemorrhage with robust performance improvement are necessary, as one study reported that 30% of patients receiving prehospital TXA did not meet indications.36

Design of the STAAMP Trial

Given the evidence supporting early TXA use in trauma, as well as the unanswered questions regarding safety, applicability in modern trauma systems, and prehospital administration, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) issued a program announcement requesting proposals for prospective clinical trials examining the effects of TXA in the treatment of patients with traumatic hemorrhage.39 In response, we designed the Study of Tranexamic Acid during Air Medical Prehospital transport (STAAMP) trial.40 The objective of this trial is to determine the effect of prehospital TXA infusion as compared to placebo during air medical transport in patients at risk of traumatic hemorrhage on 30-day mortality. We hypothesize that TXA will result in improved outcomes when administered by air medical providers during the prehospital phase in developed trauma systems. The specific aims for the STAAMP trial are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific aims of the STAAMP trial

| Primary aim | Determine whether prehospital tranexamic acid compared to placebo reduces 30-day mortality in patients at risk for traumatic hemorrhage |

| Secondary aim 1 | Determine whether prehospital tranexamic acid compared to placebo reduces the incidence of hyperfibrinolysis and coagulopathya |

| Secondary aim 2 | Determine whether prehospital tranexamic acid compared to placebo results in a lower incidence of 24-hour mortality, acute lung injury, multiple organ failure, nosocomial infection, pulmonary embolism, shock parameters, and early resuscitation requirementsb |

| Secondary aim 3 | Investigate potential novel mechanisms by which tranexamic acid alters the inflammatory response to injury independent of effects on hyperfibrinolysisc |

| Secondary aim 4 | Determine whether different dosing regimens of tranexamic acid are associated with improvements in hyperfibrinolysis, markers of coagulopathy, clinical outcomes, and the early inflammatory responsed |

Hyperfibrinolysis defined as estimated percent lysis (EPL) > 7.5% on rapid-TEG; coagulopathy defined as INR > 1.4.

ALI defined as 1992 American–European Consensus Conference definition48; MOF defined as Denver MOF score > 349; NI defined by quantitative culture data for pneumonia (> 104 CFU/mL BAL), catheter-associated bloodstream infections (> 15 CFU/segment), and urinary tract infections (> 105 organisms/mL urine); PE defined as radiographically confirmed PE by CT, echocardiogram, or ventilation/perfusion scan; Shock parameters defined as base deficit and lactate; early resuscitation requirements at 6 and 24 hours.

To include investigation of TXA effects on platelet and leukocyte activation, plasmin-mediated complement activation, and circulating cytokine levels.

Early inflammatory response defined as platelet and leukocyte activation, plasmin levels, complement activation, HMGB1 levels, circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels.

This study is designed as a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. The intervention includes both a prehospital phase and in-hospital phase. Participating sites include the University of Pittsburgh (coordinating site), University of Rochester, University of Texas San Antonio, and University of Utah. All sites are large academic level I trauma centers with active air medical programs. Eligible subjects include trauma patients undergoing air medical transport to one of the participating centers within 2 hours of injury, with systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg and heart rate (HR) >110 bpm (SBP and HR criteria need not be simultaneous).We selected these inclusion criteria to mimic the physiologic inclusion criteria from CRASH-2, while narrowing the population to those within 2 hours of injury to maximize benefit and exclude those who may be harmed. Exclusion criteria include age <18 or >90 years old, inability to obtain intravenous access, cervical spinal cord injury with motor deficit, prisoner, pregnancy, cardiac arrest > 5 minutes without return of vital signs, penetrating cranial injury, traumatic brain injury with brain matter exposed, isolated drowning or hanging victims, or wearing an opt-out bracelet (see below).

Patients meeting inclusion criteria will be randomized for the prehospital phase by the treating air medical provider. A single prehospital treatment box containing numerically labeled allocation treatment packs in blocks of 8 generated by a computer random number generator will be available on each helicopter. These packs contain identical unlabeled TXA or placebo that will be administered sequentially to enrolled subjects. TXA is stable in a wide variety of field conditions for up to 12 weeks.41 The prehospital phase includes the intervention arm in which subjects receive 1 g of TXA or the control arm in which subjects receive 1 g of identical placebo. Both TXA and the placebo will be diluted in 100 mL of normal saline (prepared on the helicopter) and infused intravenously over 10 minutes.

The treatment pack number will be provided to research staff upon arrival. This will be entered into a web-based secure program that will provide the in-hospital random allocation to the pharmacy for the in-hospital phase. All subsequent study drug administration will be prepared by the pharmacy to be identical and blinded to subjects and providers. For subjects receiving placebo in the prehospital phase, they will receive an additional 1-g placebo bolus diluted in 100 mL of normal saline over 10 minutes followed by 1 g of placebo infused over 8 hours in-hospital. Thus, placebo patients will receive no TXA throughout the study duration. Subjects receiving TXA in the prehospital phase will be randomized to one of three treatment arms for the in-hospital phase.

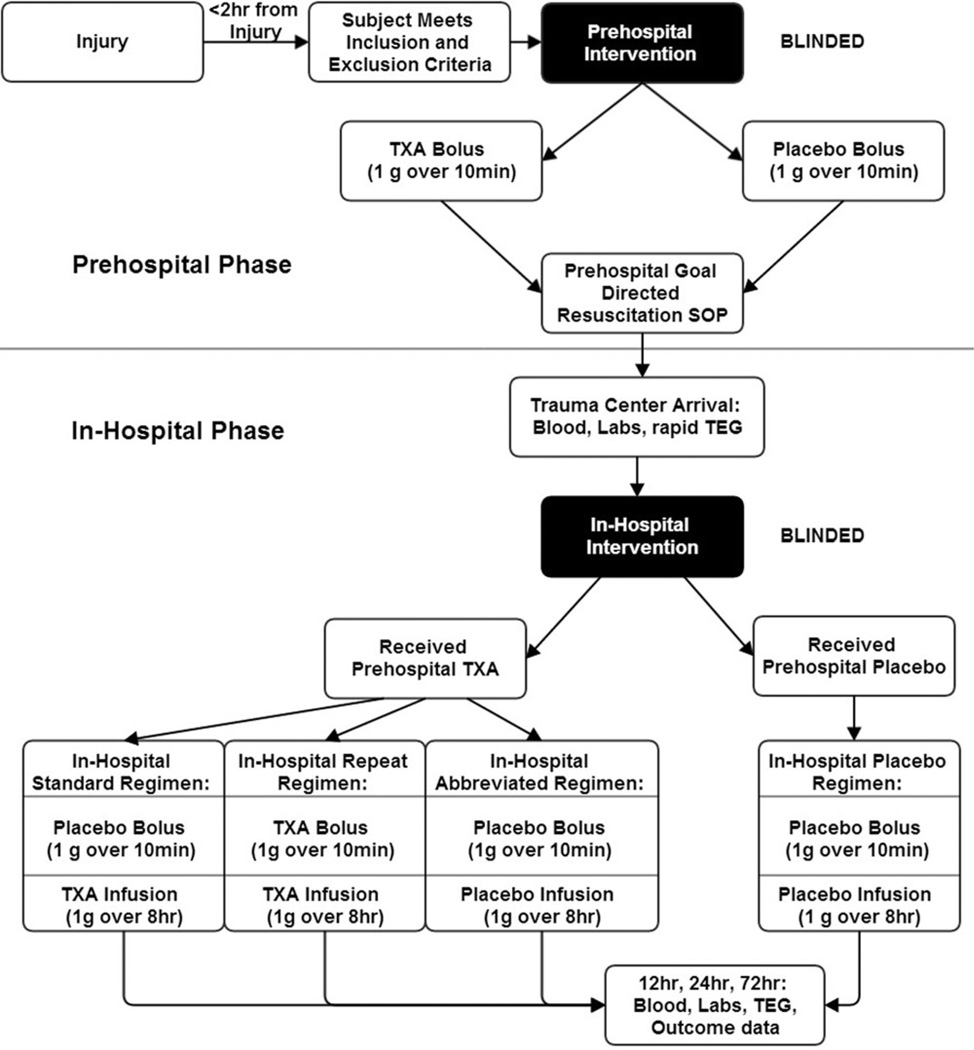

Since variable dosing regimens have been used in prior clinical studies,29,33 the optimal dosing strategy remains unclear. To address this, we have designed 3 dosing regimens that subjects assigned to prehospital TXA may receive (Figure 1). The first is the standard regimen, designed to deliver a similar total TXA dose and administration structure as the CRASH-2 trial. In-hospital subjects will receive a placebo bolus followed by TXA infusion over 8 hours. Subjects will thus receive a total 2-g dose including the prehospital TXA bolus and in-hospital TXA infusion. The second is the repeat regimen, designed to deliver a higher TXA dose. In-hospital, subjects will receive a TXA bolus followed by TXA infusion. Subjects will thus receive a total 3-g dose including the prehospital and in-hospital TXA doses. The third is the abbreviated regimen, designed to deliver only the prehospital TXA dose. In-hospital subjects will receive a placebo bolus followed by placebo infusion. Subjects will thus receive a total 1-g dose from the prehospital bolus, with no further TXA in-hospital. All patients will receive a bolus and infusion in-hospital regardless of in-hospital treatment assignment to maintain blinding during the in-hospital phase of the intervention.

Figure 1.

2-phase STAAMP trial intervention schematic.

These alternate dosing regimens were designed to provide total doses above and below the current standard regimen used in CRASH-2 and at our institution (1 g TXA bolus followed by 1 g TXA infusion over 8 hours) to examine the possibility of dose–response effects for TXA on clinical or laboratory outcomes. If higher doses prove more effective, investigation of higher TXA dosing will be warranted. However, if the abbreviated regimen produces similar benefits as higher doses, additional doses of TXA may be foregone.

To address the aims of the study, research staff will collect blood for laboratory analysis and outcome data at several time points. Upon arrival, blood will be drawn for laboratory and rapid TEG analysis. Blood will also be collected at 12, 24, and 72 hours. Laboratory analysis includes rapid TEG, conventional coagulation parameters (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio), base deficit, and d-dimer levels. As part of the investigation into the mechanisms of action, the analysis will also include measurement of activated protein C levels, plasmin–antiplasmin complex levels, serum plasmin levels, plasmin-mediated complement activation (C3a and factor B), high mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1) levels, and a panel of 10 cytokine levels. Additionally, flow cytometry and RT-PCR will be used to determine leukocyte activation and inflammatory gene expression, and the collection at serial time points will allow for an ongoing assessment of TXA effect on these parameters following repeat dosing. Mortality outcomes will be collected at 24 hours, 30 days, and in-hospital. Resuscitation requirements of packed red blood cells, plasma, platelets, and crystalloid will be collected at 6 and 24 hours. Specific adverse events to be collected in-hospital include acute lung injury (ALI), nosocomial infection (NI), multiple organ failure (MOF), seizures, and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Sample size was determined using the primary outcome of 30-day mortality and the primary comparison for the two prehospital intervention groups. We estimated a 16% baseline mortality based on CRASH-2 as well as the Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury study conducted at eight large academic level I trauma centers in the United States, which included two participating sites for this trial.42 We sought to detect an effect size of 6.4% difference in 30-day mortality. Using a two-sided alpha of 0.05 and power of 85%, 497 subjects are required per arm in the prehospital phase with a total study sample size of 994 subjects. Based on the expected volume of eligible patients across the participating sites, recruitment will occur over a 3-year period to achieve our sample size. All analyses will be conducted as intention to treat and site stratification will be accounted for in statistical tests. All outcomes will be compared between both the prehospital phase TXA and placebo groups. Outcomes will also be compared between the different TXA dosing regimens from the in-hospital phase; however, these will be primarily exploratory as the study was not powered to compare all four possible dosing regimens. Predefined subgroups selected for additional exploratory analysis include subjects defined by 1) blood transfusion status; 2) traumatic brain injury; 3) transfer status; 4) requirement for operative intervention within 24 hours of admission; 5) therapeutic anticoagulation status; and 6) massive transfusion status. Two interim analyses are planned and will be overseen by the data safety monitoring board.

This study will be performed under exception from inform consent for emergency research as outlined under U.S. Federal regulation 21 CFR 50.24.43 This represents one of the major challenges to conducting prehospital emergency research, as significant scrutiny and safeguards are in place to ensure appropriate provision of this standard. Under this regulation for emergency research, the study must meet the conditions outlined in Table 2.44

Table 2.

Requirements for exception from informed consent for emergency research

|

Although it may seem intuitive that prehospital emergency research is ideally suited to be conducted under this waiver, substantial justification and support is required by regulatory bodies to ensure all conditions are satisfactorily fulfilled prior to approving an exception from informed consent. For studies pursuing an exception from informed consent for emergency research, the institutional review board (IRB) must determine whether the proposed intervention and study fall under the regulation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). If a study does fall under the regulations of the FDA, the study must be conducted under an investigational new drug application (IND) or investigational device exemption (IDE). This study has completed the FDA IND approval process (IND# 121102). In cases where the IRB determines FDA regulations do not apply, the IRB must also determine whether the study meets the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) requirements for Emergency Research Consent Waiver under 45 CFR Part 46 and report this to the HHS Office for Human Research Protections.45

The exception from informed consent for emergency research also requires a community consultation process at each participating site. This process consists of two parts: 1) public notification of the study, and 2) community consultation. For this study, a multipronged approach was planned. The notification process includes distribution of information regarding the trial in several mediums. A website was created within the existing acute care research website for the University of Pittsburgh (acutecareresearch.org). Bumper ads on Pittsburgh Port Authority buses were designed to direct people to the website. Fliers will be distributed throughout area hospital waiting rooms and local community center boards. In-person presentations are planned for several local-area EMS, fire, and police agencies regarding the study. Additionally, an informational video will be posted on YouTube.

The consultation process involves monitoring traffic and hits on the above website. Additionally, the website allows email communication with the study coordinators either anonymously or with return contact information. Phone numbers to the coordinators are also listed and welcome direct feedback. Periodic sampling of view and attitudes of enrolled subjects and family will be recorded. The study will also be presented to the Pennsylvania Department of Health for feedback. A telephone survey will be conducted by an independent company with random digit dialing for 500 households in the study region over 4 weeks. The survey provides information regarding willingness to be enrolled and potential reservations or concerns regarding the study. It also collects demographics, social economic status, and attitudes toward emergency research in general from respondents.

Finally, opt-out bracelets will be made available to any community member by phone or by email. The bracelet is to be worn at all times by the individual who prospectively does not wish to be enrolled in the case of severe injury, and air medical providers have been trained to look for these prior to enrolling the patient. For patients who are enrolled, informed consent will be obtained to use the patient’s data from the patient or legally authorized representative as soon as feasible after in the intervention, as required for exception from informed consent. Although this process is demanding, it is necessary to assure ethically responsible and high-quality emergency research trials, while maintaining public trust and confidence. Our prior experience with the regulatory requirements and community consultation process46 have streamlined these procedures in the STAAMP trial, and allowed us to help our participating sites navigate these elements as well.

Addressing Knowledge Gaps

Pusateri et al. developed a consensus list of current knowledge gaps and research priorities regarding the use of TXA in trauma.32 This trial has the prospect of providing evidence for many of the priority areas identified. This trial is primarily designed to address pre-hospital use of TXA. This study will also rigorously collect in-hospital complications and morbidity related to the safety profile of TXA, including thromboembolic events, which have not been captured before and can address concerns related to venous thromboembolism and seizures raised in prior studies.31,33 Further, this study will address the need for additional evidence of efficacy in the civilian trauma population treated within developed trauma systems. Subjects in this trial will have the most advanced trauma care available to them, and will be able to assess the added benefit, if any, of TXA in this setting. Our secondary aims utilize sophisticated laboratory and analysis techniques to investigate the multiple potential mechanisms of action underlying any benefits seen in trauma patients due to TXA administration, including not only the impact on hyperfibrinolysis and coagulopathy, but also the off-target effects on proinflammatory mediators, the complement pathway, and inflammatory cell activation. We have planned an a priori subgroup analysis in traumatic brain injury patients to assess all efficacy and safety outcomes. Further, we will investigate the moderating effect of TXA and blood product resuscitation, and will also explore subgroup analysis outcomes among subjects who did and did not receive blood transfusion. Finally, we will evaluate potential differences in all outcomes among 3 different dosing options in subjects receiving TXA. As a result, this trial directly addresses many of the current knowledge gaps in the field of TXA for trauma.

Summary and Future Directions

Successful completion of the aims of this study will have implications for the care of both civilian and military trauma patients, and allow evidence-based decisions regarding TXA efficacy in developed trauma systems, safety profile, and optimal dosing regimens. Furthermore, the basic science component will lend insight into the mechanism of action of TXA, including both the role in anti-fibrinolysis as well as inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This trial received one of three awards funded by the DoD to investigate TXA in trauma. The Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (PI: Martin Schreiber, MD; Susanne May, PhD) and Washington University St. Louis (PI: Philip Spinella, MD) will also evaluate the use of TXA in trauma, specifically exploring issues related to dosing and traumatic brain injury. These studies, combined with the Pre-hospital Anti-fibrinolytics for Traumatic Coagulopathy and Haemorrhage (PATCH) trial underway in Australia and New Zealand,35,47 and coupled with the efforts of the Transagency Collaboration for Trauma Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC) consortium, will contribute tremendously to our understanding of the mechanism and optimal therapeutic approaches to coagulopathy in the hemorrhaging trauma patient.

Acknowledgments

This trial is supported by the following grant: Department of Defense W81XWH 13-2-0080.

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma. 2006;60:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacLeod JB, Lynn M, McKenney MG, Cohn SM, Murtha M. Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55:39–44. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000075338.21177.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahbar E, Fox EE, del Junco DJ, Harvin JA, Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Schreiber MA, Rahbar MH, Bulger EM, Phelan HA, Brasel KJ, Alarcon LH, Myers JG, Cohen MJ, Muskat P, Cotton BA. Early resuscitation intensity as a surrogate for bleeding severity and early mortality in the PROMMTT study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:S16–S23. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828fa535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shackford SR, Mackersie RC, Holbrook TL, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, Hoyt DB, Wolf PL. The epidemiology of traumatic death: a population-based analysis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:571–575. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170107016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, Coats T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma. 2003;54:1127–1130. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000069184.82147.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floccard B, Rugeri L, Faure A, Saint Denis M, Boyle EM, Peguet O, Levrat A, Guillaume C, Marcotte G, Vulliez A, Hautin E, David JS, Negrier C, Allaouchiche B. Early coagulopathy in trauma patients: an on-scene and hospital admission study. Injury. 2012;43:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trentzsch H, Huber-Wagner S, Hildebrand F, Kanz KG, Faist E, Piltz S, Lefering R TraumaRegistry DGU. Hypothermia for prediction of death in severely injured blunt trauma patients. Shock. 2012;37:131–139. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318245f6b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JB, Cohen MJ, Minei JP, Maier RV, West MA, Billiar TR, Peitzman AB, Moore EE, Cuschieri J, Sperry JL Inflammation, the Host Response to Injury Investigators. Characterization of acute coagulopathy and sexual dimorphism after injury: females and coagulopathy just do not mix. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1395–1400. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825b9f05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niles SE, McLaughlin DF, Perkins JG, Wade CE, Li Y, Spinella PC, Holcomb JB. Increased mortality associated with the early coagulopathy of trauma in combat casualties. J Trauma. 2008;64:1459–1463. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174e8bc. discussion 1463–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245:812–818. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burk AM, Martin M, Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Helm M, Lampl L, Bruckner U, Stahl GL, Blom AM, Perl M, Gebhard F, Huber-Lang M. Early complementopathy after multiple injuries in humans. Shock. 2012;37:348–354. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182471795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MJ, West M. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: from endogenous acute coagulopathy to systemic acquired coagulopathy and back. J Trauma. 2011;70:S47–S49. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821a5c24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganter MT, Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Shaffer LA, Walsh MC, Stahl GL, Pittet JF. Role of the alternative pathway in the early complement activation following major trauma. Shock. 2007;28:29–34. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3180342439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess JR, Brohi K, Dutton RP, Hauser CJ, Holcomb JB, Kluger Y, Mackway-Jones K, Parr MJ, Rizoli SB, Yukioka T, Hoyt DB, Bouillon B. The coagulopathy of trauma: a review of mechanisms. J Trauma. 2008;65:748–754. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181877a9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maegele M, Schöchl H, Cohen MJ. An up-date on the coagulopathy of trauma. Shock. 2014;41(Suppl 1):21–25. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Sawyer M, Wohlauer M, Pezold M, Barnett C, Biffl WL, Burlew CC, Johnson JL, Sauaia A. Primary fibrinolysis is integral in the pathogenesis of the acute coagulopathy of trauma. Ann Surg. 2010;252:434–442. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f09191. discussion 443–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotton BA, Harvin JA, Kostousouv V, Minei KM, Radwan ZA, Schochl H, Wade CE, Holcomb JB, Matijevic N. Hyperfibrinolysis at admission is an uncommon but highly lethal event associated with shock and prehospital fluid administration. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:365–370. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825c1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ives C, Inaba K, Branco BC, Okoye O, Schochl H, Talving P, Lam L, Shulman I, Nelson J, Demetriades D. Hyperfibrinolysis elicited via thromboelastography predicts mortality in trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maegele M, Spinella PC, Schochl H. The acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanisms and tools for risk stratification. Shock. 2012;38:450–458. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31826dbd23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutcher ME, Cripps MW, McCreery RC, Crane IM, Greenberg MD, Cachola LM, Redick BJ, Nelson MF, Cohen MJ. Criteria for empiric treatment of hyperfibrinolysis after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:87–93. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182598c70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman MP, Moore EE, Ramos CR, Ghasabyan A, Harr JN, Chin TL, Stringham JR, Sauaia A, Silliman CC, Banerjee A. Fibrinolysis greater than 3% is the critical value for initiation of antifibrinolytic therapy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:961–967. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aa9c9f. discussion 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raza I, Davenport R, Rourke C, Platton S, Manson J, Spoors C, Khan S, De’Ath HD, Allard S, Hart DP, Pasi KJ, Hunt BJ, Stanworth S, MacCallum PK, Brohi K. The incidence and magnitude of fibrinolytic activation in trauma patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:307–314. doi: 10.1111/jth.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medcalf RL. Fibrinolysis, inflammation, and regulation of the plasminogen activating system. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):132–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syrovets T, Lunov O, Simmet T. Plasmin as a proinflammatory cell activator. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:509–519. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy JH. Antifibrinolytic therapy: new data and new concepts. Lancet. 2010;376:3–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60939-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang M, Kistler EB, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Disruption of the mucosal barrier during gut ischemia allows entry of digestive enzymes into the intestinal wall. Shock. 2012;37:297–305. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318240b59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez JJ, Iribarren JL, Lorente L, Rodriguez JM, Hernandez D, Nassar I, Perez R, Brouard M, Milena A, Martinez R, Mora ML. Tranexamic acid attenuates inflammatory response in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery through blockade of fibrinolysis: a case control study followed by a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Crit Care. 2007;11:R117. doi: 10.1186/cc6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalle Lucca JJ, Li Y, Simovic M, Pusateri AE, Falabella M, Dubick MA, Tsokos GC. Effects of C1 inhibitor on tissue damage in a porcine model of controlled hemorrhage. Shock. 2012;38:82–91. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31825a3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, Caballero J, Coats T, Dewan Y, El-Sayed H, Gogichaishvili T, Gupta S, Herrera J, Hunt B, Iribhogbe P, Izurieta M, Khamis H, Komolafe E, Marrero MA, Mejia-Mantilla J, Miranda J, Morales C, Olaomi O, Olldashi F, Perel P, Peto R, Ramana PV, Ravi RR, Yutthakasemsunt S. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:23–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, Brohi K, Coats T, Dewan Y, Gando S, Guyatt G, Hunt BJ, Morales C, Perel P, Prieto-Merino D, Woolley T. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1096–101. 1101 e1091–1101 e1092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60278-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Napolitano LM, Cohen MJ, Cotton BA, Schreiber MA, Moore EE. Tranexamic acid in trauma: how should we use it? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1575–1586. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318292cc54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pusateri AE, Weiskopf RB, Bebarta V, Butler F, Cestero RF, Chaudry IH, Deal V, Dorlac WC, Gerhardt RT, Given MB, Hansen DR, Hoots WK, Klein HG, Macdonald VW, Mattox KL, Michael RA, Mogford J, Montcalm-Smith EA, Niemeyer DM, Prusaczyk WK, Rappold JF, Rassmussen T, Rentas F, Ross J, Thompson C, Tucker LD. Tranexamic Acid and trauma: current status and knowledge gaps with recommended research priorities. Shock. 2013;39:121–126. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318280409a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison JJ. Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study. Arch Surg. 2012;147:113. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison JJ, Ross JD, Dubose JJ, Jansen JO, Midwinter MJ, Rasmussen TE. Association of cryoprecipitate and tranexamic acid with improved survival following wartime injury: findings from the MATTERs II Study. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:218–225. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schochl H, Schlimp C, Maegele M. Tranexamic acid, fibrinogen concentrate and prothrombin complex concentrate: data to support prehospital use? Shock. 2014;41(Suppl 1):44–46. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipsky AM, Abramovich A, Nadler R, Feinstein U, Shaked G, Kreiss Y, Glassberg E. Tranexamic acid in the prehospital setting: Israel Defense Forces’ initial experience. Injury. 2014;45:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vu EN, Schlamp RS, Wand RT, Kleine-Deters GA, Vu MP, Tallon JM. Prehospital use of tranexamic acid for hemorrhagic shock in primary and secondary air medical evacuation. Air Med J. 2013;32:289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann C, Falzone E, Donat A, Leclerc T, Donat N, Tourtier JP. In-flight risk of venous thromboembolism and use of tranexamic acid in trauma patients. Air Med J. 2014;33:48. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Department of Defense. Program Announcement: Tranexamic Acid Clniical Research. [Accessed: March 13, 2014];Funding opportunity number: W81XWH-12-CCCJPC-TACR. Available at: file:///D:/Trauma/Trauma%20Research/STAAMP/program%20announcement%20-%20tacr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Study of Tranexamic Acid during Air Medical Prehospital transport (STAAMP) trial. NCT02086500. [Accessed: March 13, 2014]; Available at: www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02086500.

- 41.de Guzman R, Polykratis IA, Sondeen JL, Darlington DN, Cap AP, Dubick MA. Stability of tranexamic acid after 12-week storage at temperatures from −20°C to 50°C. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17:394–400. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2013.792891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier RV, Bankey P, McKinley B, Freeman B, Harbrecht BG, Johnson JL, Minei JP, Moore EE, Moore F, Nathens AB, Shapiro M, Tompkins RG, West M. Inflammation and the host response to injury, a large-scale collaborative project: patient-oriented research core-standard operating procedures for clinical care: foreward. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2005;59:762–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United States Food and Drug Adminstration. Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Section 50.24 Eception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. [Accessed: March 13, 2014]; Available at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr = 50.24.

- 44.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance fo Institutional Review Boards, Clinical Investigators, and Sponsors: Exception from Informed Consent Requirements for Emergency Research. [Accessed: April 9, 2014]; Available at: www.fda.gov/downloads/regulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm249673.pdf.

- 45.Office for Human Research Protections. Informed Consent Requirements in Emergency Research. [Accessed: April 9, 2014]; Available at: www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/hsdc97–01.html.

- 46.Prehospital Air Medical Plasma Trial (PAMPer). NCT01818427. [Accessed: July 13, 2013]; Available at: clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01818427.

- 47.Reade MC, Pitt V, Gruen RL. Tranexamic acid and trauma: current status and knowledge gaps with recommended research priorities. Shock. 2013;40:160–161. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31829ab240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American–European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauaia A, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Ciesla DJ, Biffl WL, Banerjee A. Validation of postinjury multiple organ failure scores. Shock. 2009;31:438–447. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31818ba4c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]