Abstract

Molecular characterization technology in genetically modified organisms, in addition to how transgenic biotechnologies are developed now require full transparency to assess the risk to living modified and non-modified organisms. Next generation sequencing (NGS) methodology is suggested as an effective means in genome characterization and detection of transgenic insertion locations. In the present study, we applied NGS to insert transgenic loci, specifically the epidermal growth factor (EGF) in genetically modified rice cells. A total of 29.3 Gb (~72× coverage) was sequenced with a 2 × 150 bp paired end method by Illumina HiSeq2500, which was consecutively mapped to the rice genome and T-vector sequence. The compatible pairs of reads were successfully mapped to 10 loci on the rice chromosome and vector sequences were validated to the insertion location by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. The EGF transgenic site was confirmed only on chromosome 4 by PCR. Results of this study demonstrated the success of NGS data to characterize the rice genome. Bioinformatics analyses must be developed in association with NGS data to identify highly accurate transgenic sites.

Keywords: genetically modified organisms, next generation sequencing (NGS) T-DNA, rice, risk assessment

Introduction

Genetic engineering technology is widely used in the agricultural and plant biotechnology fields, ranging from the food and feed industries to bio-pharmaceuticals and cosmetics [1,2]. The history of genetically modified (GM) technology began with the discovery of plasmid DNA, where the plasmid could be transferred from one cell to another genome [3]. Scientists subsequently applied the basic plasmid vector system principle and developed recombinant DNA technology to create genetically engineered organisms. Today, GM techniques have been applied to various research fields, including crop sciences, drug manufacturing, and animal husbandry.

The development of transgenic biotechnologies over the last 20 years has led to safety concerns regarding genetically modified organisms (GMOs), particularly in food crops and new pharmaceuticals, which are the most controversial issues. Safety concerns regarding GMOs have resulted in research, debates, and ongoing public unease. Therefore, the European Union (EU) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States proposed an authorization process in commercial GMO use; however, public apprehension for transgenic techniques remains uncertain and controversial [4,5,6,7,8].

Generally, molecular characterization and identification of GMOs are performed using Southern blots and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based detection followed by conventional sequencing methods [7]. However, these approaches are limited to evaluate whether the host genome has unintended sequence substitutions and indels [9]. Moreover, if sufficient genomic information is not available for the chosen comparative model species, it is difficult to detect the correct transgenic insert site location or sequence contamination of vector DNA [9,10].

Recent publications of GMO molecular characterizations reported the use of next generation sequencing (NGS) approaches as an effective means to detect the precise transgenic insert location [9,11,12]. High-throughput DNA sequencing technologies and bioinformatics can be coupled with NGS to offer new possibilities in drawing genetic maps with feasible costs. For these reasons, researchers have tested new approaches in the molecular characterization of GMOs using NGS technologies [9,10,12].

Here, we examined transgenic insertion sites using paired-end whole genome re-sequencing data following Yang et al. with modifications [9]. Human epidermal growth factor (EGF) was inserted into GM rice cells, which could produce EGF safety without endotoxin derived from bacteria and was used as material for this study. Deep sequencing was performed with the Illumina Hiseq2500 platforms (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). In this pilot study, we demonstrated the potential of NGS for examination of transgenic insertion loci and discuss some technical bottlenecks of this new method.

Methods

GM rice samples

The GM rice event PJKS131-2 was transformed with the EGF inserted pJKS131 vector, produced by Natural Bio-Materials Inc. (Jeonju, Korea). Taxonomically, the event PJKS131-2 was derived from Oryza sativa L. cv. Dongjin. The T-vector was transformed with rice callus as described by Chan et al. [13]. Transgenic rice calli were incubated with 50 mg/L of hygromycin B antibiotic (A.G. Scientific Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for selection. The GM rice callus samples were subjected to NGS and further validated by PCR amplification.

DNA extraction and whole genome shotgun library and sequencing

The calli of GM rice event PJKS131-2 were collected and stored at -80℃. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method in liquid nitrogen. Genomic DNA quality was evaluated by 0.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Following the quality check, genomic DNA was sheared with average 500 bp fragment sizes. Truseq DNA PCR free Library Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc.) was used to construct the DNA library according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quality of constructed DNA libraries was confirmed by the LabChip GX system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA libraries were sequenced with 150-bp paired-end sequencing using Illumina Hiseq2500.

Transgenic insertion analysis

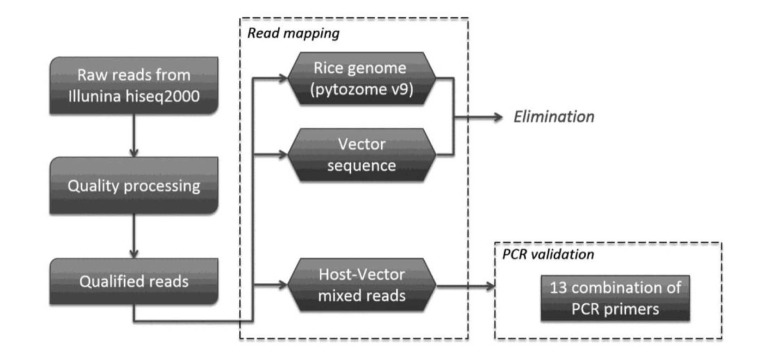

Initially, paired-end reads were filtered out by phred scores < 20 and duplicate sequences were removed. After filtration, DNA fragments were consecutively mapped against the rice reference genome (phytozome v9 [14]) and T-vector sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1). The transgene insertion types were classified by adaptation and modification of the analytical strategies reported in Yang et al. [9]. Fig. 1 shows the workflow applied in this method. Initially, all NGS reads were individually mapped to the rice reference genome and transgenic vector (types A and C in Yang et al. [9]). Subsequently, these NGS reads were eliminated to conduct the following analyses. NGS reads not classified as above were classified into the following two classes: one side of the NGS read matched the reference genome, (1) the other one matched to vector (type B in Yang et al. [9]); or (2) one side of the NGS read exhibited both elements from the rice reference and transgenic vector (types D and E in Yang et al. [9]).

Fig. 1. Summary of the work-flow. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Experimental validation of transgenic inserts

Each of the 13 combination primer sets was designed congruent with the transgenic insertion region orientation. PCR was conducted using DNA polymerase (Solgent Co., Daejeon, Korea) following the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction was performed under the following conditions: a pre-denaturation step at 95℃ for 5 min; denaturation at 95℃ for 60 s; 30 amplification cycles, including annealing at 60℃ for 45 s, and elongation at 72℃ for 120 s; and a final elongation at 72℃ for 5 min.

Results

Whole genome re-sequencing and mapping to discover the transgenic position

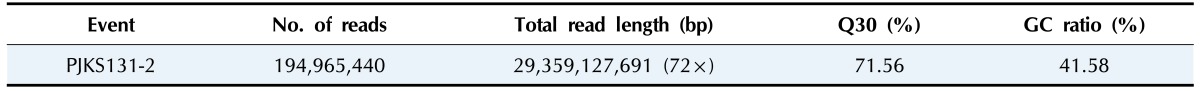

The transgenic GM rice site, PJKS131-2, was detected by performing whole genome re-sequencing using callus tissue. Genomic DNA libraries were constructed with an average 500 bp and both ends were read with 150 bp paired-end sequencing methods. A total length of raw sequencing reads were 29.3 Gb (~194.9 million reads), which showed ~72× coverage in the total read length (Table 1). Following quality control processing, reads with average phred scores ≥ 30 were estimated at %71.5% (Table 1).

Table 1. Whole genome sequencing summary.

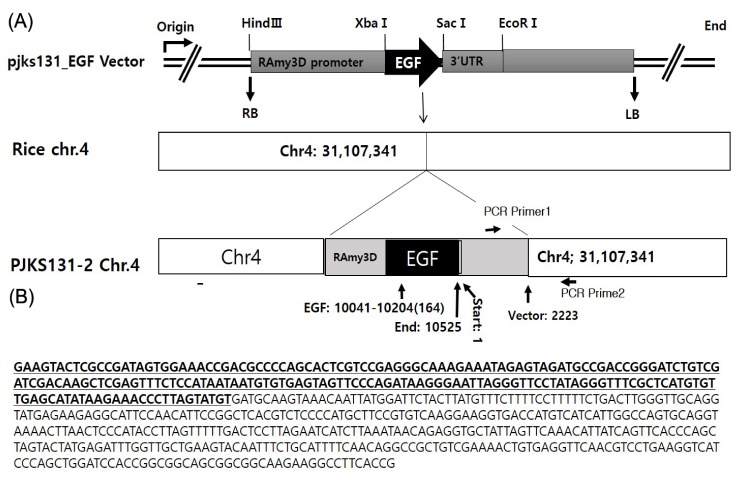

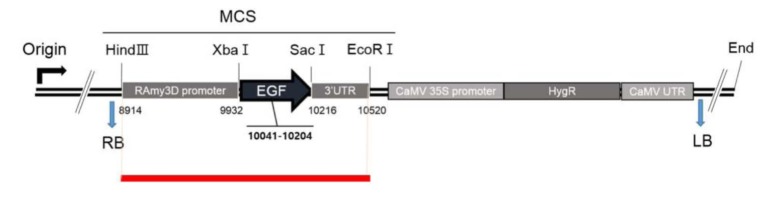

The types of mapped reads were classified by alignment of all NGS reads to the rice reference genome and transgenic vector sequences. Fig. 2 shows construction of the pJKS131 transgenic vector. Reads were aligned on the cloning vector positions 8,500 bp to 10,500 bp, similar to transgenic insert locations. Detailed mapping strategies were described in the Methods. The transgene insertion site was identified by classifying reads where one end matched the host genome and the other end matched the vector sequences (i.e., types B, D, and E) mapped back to the rice chromosome and known vector sequences. Eleven pairs of reads were identified on rice chromosome including chromosome 4. The total mapped reads described above were compatible with the transgenic vector backbone sequences.

Fig. 2. Schematic drawing of the transgenic vector genome. Red line represent the region of mapped reads. MCS, multiple cloning site; RB, right border; LB, left border.

PCR validation of mapping prediction

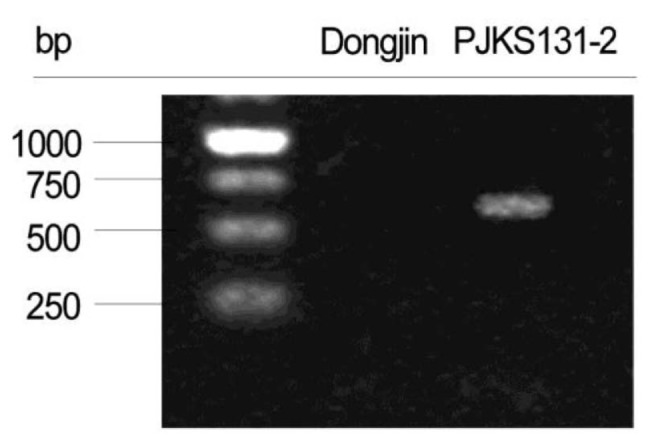

Thirteen PCR primers designed based on mapping direction validated the mapping results of 10 transgenic insert candidates. PCR results confirmed the target EGF sequence was successfully inserted on rice chromosome 4 (Figs. 3 and 4). The remaining reads were concluded to be artifacts, because all matches were not detected with PCR.

Fig. 3. Polymerase chain reaction validation of transgenic site.

Fig. 4. Transgenic position of epidermal growth factor (EGF) locus on the rice chromosome 4 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to identify T-DNA junction sequence. (A) The EGF is inserted on the position 31,104,341 of the chromosome 4. (B) The bold with underline is T-DNA sequence of the vector 2,026-2,223 bp and the next bases is rice transgenic locus chromosome 4 (31107341-31107690) in the fragment amplified by PCR test primer1 (5' TACCTGCATGCTGCGGTGAAG 3') and primer2 (5'AGGGCTGTGTAGAAGTACTCGC 3').

Discussion

Recent developments in NGS methods and accompanying bioinformatics tools have paved the way for ongoing genomics research widely used in the agricultural biotechnology field. Consequently, several studies reported new approaches in GM crop safety assessment using NGS platforms [10,11,12]. In our study, we investigated EGF inserted GM rice events using NGS technology and bioinformatics to test the potential uses of this new approach in molecular assessment of transgenic organisms.

Results were successful in differentiating NGS read types using in silico analyses from GM rice, PJKS131-2 and hypothetically, the outcome was acceptable in terms of read classification. However, as a validation step, we experienced unexpected problems. Consistent with mapping and aligning data, we considered all possible transgenic insertion directions on the rice chromosomes and designed PCR primers based on loci information. Among the primers, except for locus specific primers on chromosome 4, results showed all matches were mismatches, which was caused by computational errors derived from analogous sequences between the rice genome and the transgenic vector. Therefore, we concluded it is essential to develop more accurate algorithms based on the transformation vector.

In addition, it is important to note our experimental sample was collected from rice callus tissues, with Agrobacterium co-incubation and a plant cell suspension culture system. Transgenic plant cell suspension culture system exhibits several advantages, including a low microorganism risk and chemical contamination, simple cell culture methods, economical facilities, and stable productivity. However, it is difficult to obtain pure genomic DNA of the host plant without plasmid DNA mixing using the plant cell culture method. We eliminated NGS raw reads mapped only against vector DNA (type C), however if raw reads contained too many vector backbone sequences, problems in further bioinformatics analyses would still occur. Further studies are required with appropriate controls of GM plants in cell culture environments.

In the present study, we completed a proof-of-concept experiment to examine the molecular characterization of a recombinant-protein produced GM rice event using NGS methods. New approaches have recently been reported to assess the development and release of GM crops, however these techniques are not popularized in the field of GM risk assessment. However, previous studies in other disciplines have successfully established NGS, but for practical reasons, it has not been easy to apply this new method for testing GMOs. NGS strategies largely depend on sample quality, amount of data, and subsequent bioinformatics analyses. Therefore, it is critical proper guidelines to discovery transgenic site by NGS data matched and PCR test in the GMOs established and required.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of bioinformatics team of National Instrumentation Center for Environmental management in Seoul National University. This work was supported by Next-Generation BioGreen21 program (PJ01131301), Rural Development Administration of the Korean government.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data including one figure can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-13-81-s001.pdf.

pJKS131 vector sequence to transfer the EGF to the rice genome.

References

- 1.Sabalza M, Christou P, Capell T. Recombinant plant-derived pharmaceutical proteins: current technical and economic bottlenecks. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36:2367–2379. doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schürch C, Blum P, Zülli F. Potential of plant cells in culture for cosmetic application. Phytochem Rev. 2008;7:599–605. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen SN, Chang AC, Boyer HW, Helling RB. Construction of biologically functional bacterial plasmids in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:3240–3244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.11.3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Parliament. Commission Implementing Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on genetically modified food and feed. European Union Legislation. OJ L 268, 1-23. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Parliament. REGULATION (EC) No 1830/2003 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labelling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified organisms and amending Directive 2001/18/EC. European Union Legislation. OJ L 268, 24-28. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Parliament. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 503/2013 of 3 April 2013 on applications for authorisation of genetically modified food and feed in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council and amending Commission Regulations (EC) No 641/2004 and (EC) No 1981/2006. European Union Legislation. OJ L 157, 1-48. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Guideline for the conduct of food safety assessment of foods derived from recombinant-DNA plants. Rome: FAO; 2003. Rep. No. CAC/GL 45-2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Guideline for the conduct of food safety assessment of foods derived from recombinant-DNA plants. Rome: FAO; 2003. Rep. No. CAC/GL. 68-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Wang C, Holst-Jensen A, Morisset D, Lin Y, Zhang D. Characterization of GM events by insert knowledge adapted re-sequencing approaches. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2839. doi: 10.1038/srep02839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauwels K, De Keersmaecker SC, De Schrijver A, du Jardin P, Roosens NH, Herman P. Next-generation sequencing as a tool for the molecular characterisation and risk assessment of genetically modified plants: added value or not. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2015;45:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovalic D, Garnaat C, Guo L, Yan Y, Groat J, Silvanovich A, et al. The use of next generation sequencing and junction sequence analysis bioinformatics to achieve molecular characterization of crops improved through modern biotechnology. Plant Genome. 2012;5:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahler D, Schauser L, Bendiek J, Grohmann L. Next-generation sequencing as a tool for detailed molecular characterisation of genomic insertions and flanking regions in genetically modified plants: a pilot study using a rice event unauthorised in the EU. Food Anal Methods. 2013;6:1718–1727. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan MT, Chang HH, Ho SL, Tong WF, Yu SM. Agrobacterium-mediated production of transgenic rice plants expressing a chimeric alpha-amylase promoter/beta-glucuronidase gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:491–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00015978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodstein DM, Shu S, Howson R, Neupane R, Hayes RD, Fazo J, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

pJKS131 vector sequence to transfer the EGF to the rice genome.