Abstract

The role of molecular mechanisms in the regulation of leaf hydraulics (Kleaf) is still not well understood. We hypothesized that aquaporins (AQPs) in the bundle sheath may regulate Kleaf. To examine this hypothesis, AQP genes were constitutively silenced using artificial microRNAs and recovery was achieved by targeting the expression of the tobacco AQP (NtAQP1) to bundle-sheath cells in the silenced plants. Constitutively silenced PIP1 plants exhibited decreased PIP1 transcript levels and decreased Kleaf. However, once the plants were recovered with NtAQP1, their Kleaf values were almost the same as those of WT plants. We also demonstrate the important role of ABA, acting via AQP, in that recovery and Kleaf regulation. These results support our previously raised hypothesis concerning the role of bundle-sheath AQPs in the regulation of leaf hydraulics.

Keywords: abscisic acid (ABA), artificial microRNA (amiRNA), aquaporins (AQPs), bundle sheath, leaf hydraulic conductivity (Kleaf), plasma membrane intrinsic proteins (PIPs)

The idea that aquaporins (AQPs) control the movement of water into the leaf (i.e., radial hydraulic conductance) has been suggested by several research groups.1-4 Antisense silencing of multiple PIP genes and a single PIP knockout2,3 have been used to demonstrate that down-regulation of AQPs negatively affects leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf).

As the axial vascular-hydraulic structure of the mature leaf is constant, the assumption is that a substantial portion of the dynamic hydraulic regulation in non-embolized or undamaged xylem is controlled via the radial or extravascular movement of water through the parenchymal tissue that surrounds the xylem elements (Sack & Holbrook, 2006). Recent studies have suggested that, in Arabidopsis, the leaf radial in-flow rate is controlled by the vascular bundle sheath.5-7 Tightly wrapped around the entire vascular system, the bundle sheath acts as barrier to efflux from the xylem vessels. It has been suggested that bundle-sheath cells sense stress signals within the xylem sap and respond by changing their ‘across-the-pipe-wall’ (radial) hydraulic conductivity accordingly. This most likely occurs via downregulation of the AQP activity in bundle-sheath cells, which leads to a decrease in the osmotic water permeability (Pf) of those cells.7,8 This, in turn, reduces the flow of water into the leaf, which decreases the leaf water potential (Ψleaf). Indeed, Prado et al. (2013) demonstrated a significant role for vascular parenchyma PIP2;1 expression in the regulation of whole-rosette hydraulics. Recently, we demonstrated that multiple and specific silencing of PIP1 genes by artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs) in the whole plant (35S promoter) or specifically in bundle-sheath cells (SCR promoter8) reduces Kleaf and further confirmed the role of bundle-sheath PIP1 AQPs in the regulation of leaf hydraulics.9

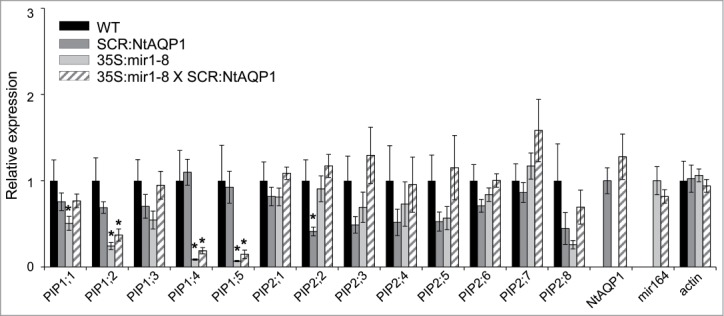

In the current study, we attempted to restore the Kleaf of these plants by expressing AQP specifically in bundle-sheath cells. In order to reduce the possibility of post-transcriptional or translational regulation, we used a heterologous aquaporin gene from tobacco (NtAQP1), which has been found to play a role in the regulation of plant hydraulic conductivity.10,11 Thus, 35S:mir plants were crossed with SCR:NtAQP1 plants expressing the tobacco Aquaporin1 – NtAQP1 gene under a bundle-sheath-specific promoter [SCARECROW (SCR)] to yield double (SCR:NtAQP1 and 35S:mir1) lines. We then followed PIP expression in the enriched bundle sheath tissue.12 In 35S:mir1–8, all of the PIP1 genes except for PIP1:3 were down-regulated in the enriched bundle sheath tissue. The expression of NtAQP1 in the bundle sheath of the control plants (SCR:NtAQP1) was similar to that observed in the WT control plants, except for the down-regulation of PIP2:2. In the 35S:mir1–8 plants expressing SCR:NtAQP1, we observed PIP1 downregulation similar to that observed in its 35S:mirPIP1 parent line, with the exception of the up-regulation of PIP1:1. Expression of NtAQP1 and mir164 was observed only in the SCR:NtAQP1 and 35S:mirPIP1XSCR:NtAQP1 and 35S:mir1–3and 8 lines, respectively (Fig. 1). In addition, SCR:NtAQP1 and 35S:mirPIP1XSCR:NtAQP1plants had similar NtAQP1 transcript levels, suggesting that NtAQP1 is not downregulated by amiRNApip1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Relative expression profile of the PIP genes in the leaf midveins. Columns indicate the mean (± SE) PIP transcript levels (quantitative RT-PCR) in 35S:mir1–8 plants, plants with bundle sheath-specific expression of NtAQP1 (SCR:NtAQP1), 35S:mir1–8 plants expressing the bundle-sheath NtAQP1 (35S:mir1–8 × SCR:NtAQP1) and the control (WT). The presented data were normalized to the WT. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05, n = 5 independent biological repetitions) between treatments and the control based on the raw transcript levels, as calculated using Dunnett's method. Data were normalized to Actin2 levels.

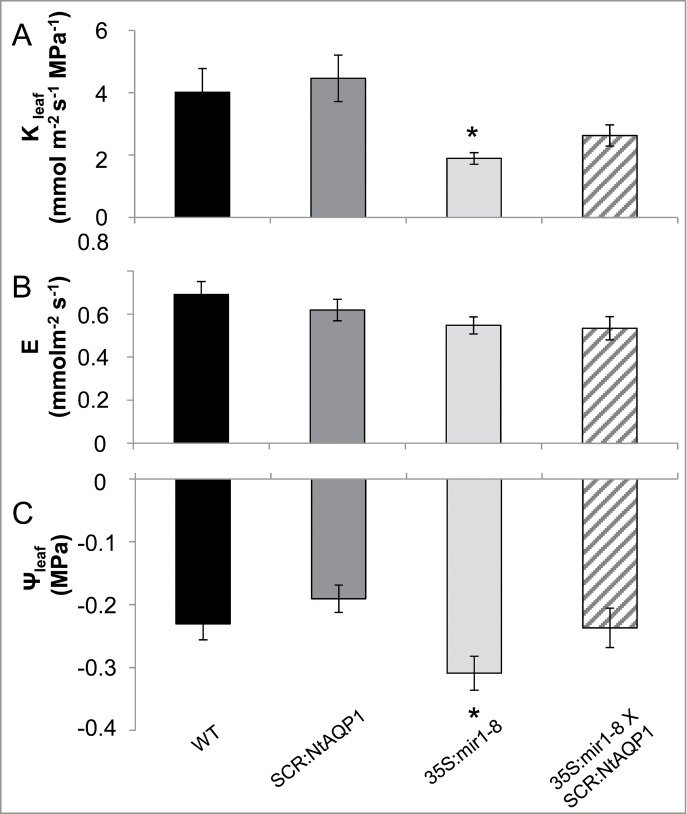

Kleaf was measured using a detached-leaf approach7 based on the determination of the transpiration rate (E) and leaf water potential (Ψleaf), which were then used to calculate Kleaf (ratio of E to Ψleaf; Fig. 2). The Kleaf of the 35S:mir1–8 line was significantly reduced as compared to that of the control. In contrast to the 35S:mir1–8 plants, the Kleaf of the 35S:mir1–8XSCR:NtAQP1 line was no different from that of the control. This intermediate value suggests that the expression of NtAQP1 in the bundle-sheath cells partially restored the transport of water in the 35S:mir1–8 plants (Fig. 2). An additional possibility is that the increased Kleaf observed in the 35S:mirPIP1XSCR:NtAQP1 plants is due to the upregulation of PIP1;1 in those plants, as compared to the 35S:mirPIP1–8 plants (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Leaf hydraulic conductivity (Kleaf) of the AQP-modified lines. Leaves were harvested from each of the tested lines and their petioles were immediately immersed in artificial xylem sap (AXS). After 1 h, (A) Kleaf was calculated for each individual leaf by dividing (B) the whole-leaf transpiration rate, E, by (C) the absolute value of the leaf water potential, Ψleaf. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05) between a genotype and the WT, as calculated using Dunnett's method. Data are means (±SE ) from 14–17 replicates from 2 independent experiments.

The fact that Ψleaf and Kleaf could be recovered by targeting NtAQP1 in the bundle-sheath cells of the silenced plants (35S:mir1–8XSCR:NtAQP1) lends additional support to the theory that bundle-sheath AQPs can regulate the movement of water into bundle-sheath cells, as well as Kleaf (or xylem efflux;4,6,7,9). Nevertheless, the fact that these plants showed only partial recovery (Fig. 2) could be related to the expression level induced by the SCR promoter. An additional explanation could be related to the fact that those plants expressed the silencing agent constitutively. Thus, their entire development proceeded in the presence of strong down-regulation of multiple AQP expression in the bundle-sheath cells. Some developmental and or physiological mechanisms might be affected by this silencing. Complete recovery of hydraulic flow was observed when only one AQP was knocked-out and recovered in the vascular system, as recently reported by Prado (2013).4

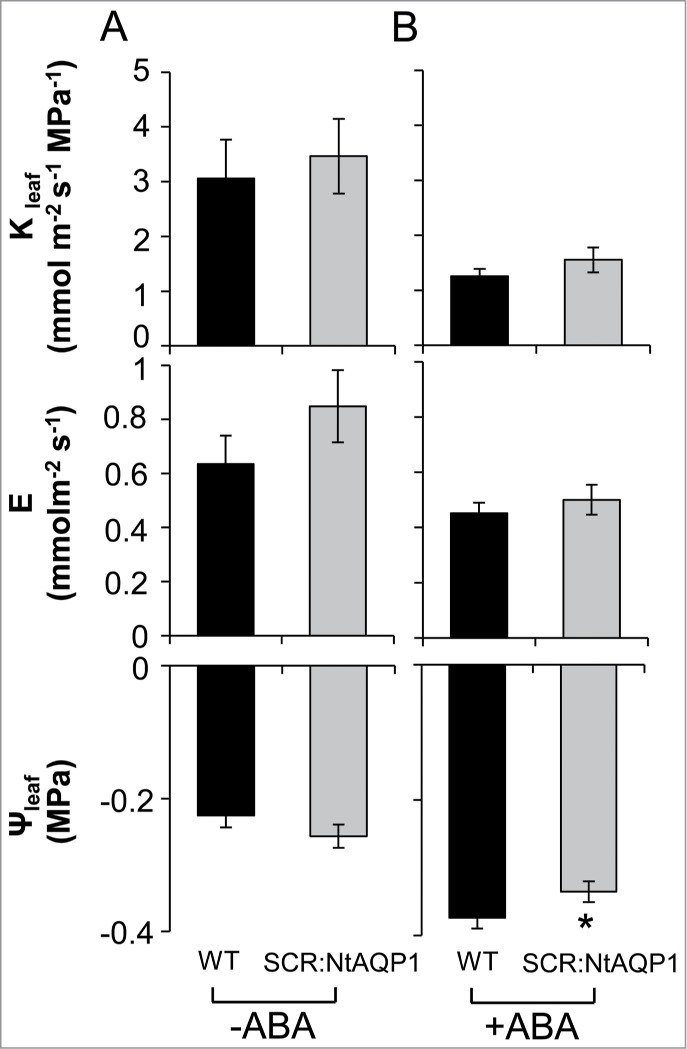

The fact that NtAQP1expressed in the bundle-sheath cells of WT plants (SCR:NtAQP1) had no impact on Kleaf in well-irrigated plants (Fig. 3) is surprising, as this channel was previously reported to contribute to hydraulic conductivity under stress.10,11,13 A possible explanation for this phenomenon might be related to an inherently high Pf of the bundle-sheath cells that allows maximal Kleaf under favorable growing conditions.

Figure 3.

Treatment with ABA led to higher leaf water potential (Ψleaf) in the SCR:NtAQP1 line. Leaves were harvested from SCR:NtAQP1 and control plants and fed AXS without ABA (-ABA; A) or with 10 μM ABA (+ABA; B) through their petioles. After 1 h, Kleaf was calculated for each individual leaf by dividing the whole-leaf transpiration rate, E, by the absolute value of the leaf water potential, Ψleaf. The asterisk represents a significant difference between SCR:NtAQP1 and the WT (t test, P < 0.05). Data are means (±SE ) of values from 12–14 replicates from 2 independent experiments.

This assumption led us to examine plants treated with 10 μM ABA, which is known to decrease Kleaf by inhibiting AQPs in the veins.6,7 Under ABA treatment conditions, we observed a significant decrease in Ψleaf in the WT; whereas SCR:NtAQP1 plants showed higher (less negative) Ψleaf levels than the WT (no differences were observed in the transpiration rates of the different plants). This suggests that NtAQP1 facilitates the movement of water into the leaf through the bundle sheath and is not post-transcriptionally regulated by ABA. However, the Kleaf of the SCR:NtAQP1 plants was not significantly different from that observed in the control (Fig. 3).

The concentration of ABA in the xylem increases under abiotic stress conditions14 and this leads to reduced Ψleaf and Kleaf via a reduction of the Pf of the bundle-sheath cells, possibly due to reduced expression and/or activity of AQP.2,6,7 Under these conditions, an artificial increase in AQP expression in the bundle-sheath cells should increase water influx, thus Ψleaf, as observed in our ABA-treated leaves (Fig. 3). Moreover, post-translational mechanisms that might reduce AQP activity under stress conditions seem not to act on NtAQP1, as this channel is known as a stress-induced AQP.11,13 High root hydraulic conductivity was maintained in stressed tomato plants that over-expressed NtAQP1, as compared with the control plants whose root hydraulic conductivity was sharply reduced in response to the stress.10

Our results emphasize the dynamic role of the bundle sheath in controlling leaf hydraulic conductance in response to vascular signals. These results underscore the importance of the bundle sheath's role as a control center, balancing soil-root long term signals and the behavior of the stomata, to regulate the leaf's water status.

References

- 1. Cochard H, Venisse J-S, Barigah TS, Brunel N, Herbette S, Guilliot A, Tyree MT, Sakr S. Putative role of aquaporins in variable hydraulic conductance of leaves in response to light. Plant Physiol 2007; 143:122-33; PMID:17114274; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.106.090092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martre P, Morillon R, Barrieu F, North GB, Nobel PS, Chrispeels MJ. Plasma membrane Aquaporins play a significant role during recovery from water deficit. Plant Physiol 2002; 130:2101-10; PMID:12481094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.009019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Postaire O, Tournaire-Roux C, Grondin A, Boursiac Y, Morillon R, Schaeffner AR, Maurel C. A PIP1 aquaporin contributes to hydrostatic pressure-induced water transport in both the root and rosette of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2010; 152:1418-30; PMID:20034965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.109.145326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prado K, Boursiac Y, Tournaire-Roux C, Monneuse J-M, Postaire O, Da Ines O, Da Ines O, Schäffner AR, Hem S, Santoni V, et al. Regulation of Arabidopsis leaf hydraulics involves light-dependent phosphorylation of aquaporins in veins. Plant Cell 2013; 25:1029-39; PMID:23532070; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.112.108456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ache P, Bauer H, Kollist H, Al-Rasheid KAS, Lautner S, Hartung W, Hedrich R. Stomatal action directly feeds back on leaf turgor: new insights into the regulation of the plant water status from non-invasive pressure probe measurements. Plant J 2010; 62:1072-82; PMID:20345603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pantin F, Monnet F, Jannaud D, Costa JM, Renaud J, Muller B, Simonneau T, Genty B. The dual effect of abscisic acid on stomata. New Phytol 2013; 197:65-72; PMID:23106390; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/nph.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shatil-Cohen A, Attia Z, Moshelion M. Bundle-sheath cell regulation of xylem-mesophyll water transport via aquaporins under drought stress: a target of xylem-borne ABA? Plant J 2011; 67:72-80; PMID:21401747; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sade N, Galle A, Flexas J, Lerner S, Peleg G, Yaaran A, Moshelion M. Differential tissue-specific expression of NtAQP1 in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a role for this protein in stomatal and mesophyll conductance of CO2 under standard and salt-stress conditions. Planta 2014; 239:357-66; PMID:24170337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00425-013-1988-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sade N, Shatil-Cohen A, Attia Z, Maurel C, Boursiac Y, Kelly G, Granot D, Yaaran A, Lerner S, Moshelion M. The role of plasma membrane aquaporins in regulating the bundle sheath-mesophyll continuum and leaf hydraulics. Plant Physiol 2014; 166:1609-20; PMID:25266632; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.114.248633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sade N, Gebretsadik M, Seligmann R, Schwartz A, Wallach R, Moshelion M. The role of tobacco aquaporin1 in improving water use efficiency, hydraulic conductivity, and yield production under salt stress. Plant Physiol 2010; 152:245-54; PMID:19939947; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.109.145854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Siefritz F, Tyree MT, Lovisolo C, Schubert A, Kaldenhoff R. PIP1 plasma membrane aquaporins in tobacco: from cellular effects to function in plants. Plant Cell 2002; 14:869-76; PMID:11971141; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.000901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown NJ, Palmer BG, Stanley S, Hajaji H, Janacek SH, Astley HM, Parsley K, Kajala K, Quick WP, Trenkamp S, et al. C-4 acid decarboxylases required for C-4 photosynthesis are active in the mid-vein of the C-3 species Arabidopsis thaliana, and are important in sugar and amino acid metabolism. Plant J 2010; 61:122-33; PMID:19807880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mahdieh M, Mostajeran A, Horie T, Katsuhara M. Drought stress alters water relations and expression of PIP-type aquaporin genes in Nicotiana tabacum plants. Plant Cell Physiol 2008; 49:801-13; PMID:18385163; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/pcp/pcn054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tuteja N. Abscisic Acid and abiotic stress signaling. Plant Signal Behav 2007; 2:135-8; PMID:19516981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/psb.2.3.4156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]