Abstract

Background

Patients suffering from burn injury are at high risk for subsequent infection. Thermal injury followed by endotoxemia may result in a “second hit,” causing an exaggerated inflammatory response with increased morbidity and mortality. The role of the intestine in this “second hit” response is unknown. We hypothesized that remote thermal injury increases the inflammatory response of intestinal mucosa to subsequent treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Methods

Mice underwent sham or scald injury. Seven days after injury, mice were treated with LPS. Blood and bowel specimens were obtained. Serum and intestinal inflammatory cytokines were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Changes in TLR-4 pathway components in intestine were measured by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Western blot, and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Intestinal leukocyte infiltration was analyzed by myeloperoxidase assay.

Results

A “second hit” of injected LPS resulted in increased IL-6 in intestine of burned mice compared with sham. Similarly, jejunal IL-6 mRNA levels increased in mice with prior thermal injury, suggesting a transcriptional mechanism. Of transcription factors known to drive IL-6 expression, only AP-1 activation was significantly elevated by a “second hit” of LPS.

Conclusion

Prior thermal injury potentiates LPS-induced IL-6 cytokine production in intestine. These results indicate a heightened inflammatory response to a second hit by intestine after burn injury.

Keywords: IL-6, intestinal mucosa, burn, TLR-4, AP-1

INTRODUCTION

The inflammatory response to thermal injury is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Despite improvements in critical care, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis remain the leading cause of death in intensive care units [1–3]. Infection complicates the hospital course of as many as 50% of patients admitted with thermal injuries, and may be responsible for as many as 75% of burn related deaths [4]. In these patients, the acute inflammatory insult of thermal injury is followed by infection, which can represent a “second hit” to the patient [5]. Under these circumstances, a normally well-tolerated insult, such as pneumonia, may lead to an exaggerated inflammatory response and progression to multiple organ failure with associated high morbidity and mortality. Burn patients appear to be especially susceptible to a “second hit.” The development of pneumonia is associated with increased mortality, and sepsis is associated with at least 50% mortality in this patient population [6, 7]. Thus, attempts to decrease morbidity and mortality following thermal injury require understanding the effect of the “first hit” on the “second hit.” Despite intensive study, the etiology of susceptibility to the “second hit” remains incompletely understood.

Following systemic injury, the intestinal mucosa produces multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines. Prior studies investigating the role of the intestine in the inflammatory response to thermal injury have shown increased gut bacterial translocation and elevation of plasma endotoxin and IL-6 after burn [8, 9]. Another study utilizing in situ hybridization in mouse intestinal lamina propria demonstrated increased IL-6 expression after burn [10]. Preliminary studies suggest a role for the intestinal mucosa in the second hit. Ex vivo experiments have shown that enterocytes harvested from previously burned animals produced more IL-6 in the presence of LPS compared with enterocytes from control animals [11]. The mechanisms of this altered responsiveness are unknown.

In order to examine the role of the intestine in the second hit after thermal injury, we investigated the effect of remote thermal injury on the inflammatory response to subsequent endotoxemia. We hypothesized that remote thermal injury increases the inflammatory response of intestinal mucosa to subsequent treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

METHODS

Experimental Conditions

Male C57/BL6 mice weighing 22–28 g were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), fed standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum, and acclimated for 1 wk in a climate-controlled room with a 12-hlight-dark cycle. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Cincinnati.

Thermal injury was induced as described previously with minor modifications [12]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital 60 mg/kg intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection and inhaled isoflurane (1.5%). Dorsal fur was removed by clipping, and mice were exposed to 90 °C water for nine s to create a 25% total body surface area full thickness burn. Sham mice were exposed to room temperature water. All mice were resuscitated immediately with 1 mL i.p. normal saline, allowed to recover in a warmed oxygen tent, and then housed individually. In initial experiments, we examined the effect of sham or thermal injury on serum cytokine levels in mice sacrificed at 1, 4, or 7 d after injury.

In subsequent experiments, a “second hit” of inflammation was induced by i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg LPS (E. coli 0111:B4; Calbiochem La Jolla, CA) 7 d after sham or burn injury. Additionally, we tested the effect of LPS injection in otherwise untreated mice. Mice were sacrificed at 1 or 4 h after LPS injection. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture, and serum separated by centrifugation, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Small and large bowel were removed and irrigated with ice-cold normal saline. Large bowel was procured whole. Small bowel mucosa was harvested by scraping as described previously [13]. Specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Tissue Extraction

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared as described previously [13]. All steps were carried out on ice. Tissue samples were homogenized in 0.5 mL of buffer A (10-mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5-mmol/L MgCl2, 10-mmol/L KCl, 1-mmol/L DTT, and 1-mmol/L PMSF), incubated for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 850 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were resuspended in 1.5× cell volume of buffer A with 0.1% Triton X-100, incubated for 10 min, and centrifuged as above. The supernatant was removed and saved as the cytoplasmic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in 300 μL of buffer A, centrifuged as above, and resuspended in 1 cell volume of a buffer of 20-mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol (vol/vol), 420-mmol/L NaCl, 1.5-mmol/L MgCl2, and 0.2-mmol/L EDTA. After incubation for 30 min, the nuclear fraction was recovered by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Fractions were assayed for protein concentration (BCA Protein Assay Kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Cytokine analysis was performed as previously described [14]. Jejunal scrapings were sonicated for two 10 s periods in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and 2 mM PMSF (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Colon whole bowel specimens were first homogenized, then sonicated for one 10 s period in this same solution. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4 °C for 45 min. Supernatant density was determined using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). IL-6 was measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum IL-6 is expressed as pg/mL and intestinal IL-6 is expressed as ng/g protein.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts of intestinal tissue were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described previously [13]. Double-stranded consensus oligonucleotides of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) or activator protein 1 (AP-1) (Promega, Madison, WI) or consensus and mutant oligonucleotides of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were end labeled with (32P) gamma-adenosine triphosphate (γATP) (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) using polynucleotide kinase T4 (Promega).

End-labeled probe was purified from unincorporated (32P) γATP using a purification column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Binding reactions (total volume 15 μL) with equal amounts of nuclear extracts (20 μg) and oligonucleotide and buffer containing 20% glycerol (vol/vol), 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 250 mM NaCl, and 0.25 μg/μL poly[d(I-C)] (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH) were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Samples were subjected to electrophoretic separation on a nondenaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel at 100 V. Blots were dried at 53 °C for 3 h and analyzed by exposure to PhosphorImager screen (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) or autoradiography film.

Western Blot Analysis

Equal concentrations of protein were boiled in equal concentrations of loading buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 10% 2-mercaptoethanol) for 5 min, then separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). For TLR-4 analysis, membranes were blocked with 10% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.6) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TTBS), for 2.5 h, incubated overnight with anti-TLR4 antibody (H-80; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:500 dilutions in 5% milk, washed three times in TTBS, and incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary for 60 min. The blots were washed in TTBS three times, incubated in Western Blotting Luminol reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and exposed on radiographic film (X-Omat AR; Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY). Western blot for MD-2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was performed similarly except that 10% milk was used.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from jejunal mucosal samples by a commercially available kit (RNeasy and Qiashredder; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically, and the purity verified by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel. cDNA was synthesized, and quantitative RT- PCR performed using a commercially available kit (RT2 PCR Array First Strand Kit, Mouse Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway Microarray RT2 Profiler PCR Array; SuperArray Bioscience, Frederick, MD) and analyzed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data analysis was performed utilizing manufacturer’s software. Experiments were performed three times in order to ensure reproducibility.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Assay

Intestinal tissue (100 mg) was homogenized in 2 mL of homogenization buffer (3.4 mmol/L KH2PO4, 16 mmol/L Na2HPO4, pH 7.4). After centrifugation for 20 min at 10,000 g, the pellet was resuspended in 10 volumes of re-suspension buffer (43.2 mmol/L KH2PO4, 6.5 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium, pH 6.0) and sonicated for 10 s. After heating for 2 h at 60°C, the supernatant was reacted with 3,3′,3,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, and the optical density was read at 655 nm [15].

Statistical Analysis

Experiments with two groups were compared with Student’s t-test. Experiments with multiple groups were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. Where applicable, data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Burn injury causes an intense initial systemic inflammatory response, resulting in increased pro-inflammatory cytokines levels that subsequently resolve. In initial experiments, we examined the effect of sham or thermal injury on serum cytokine levels. Mice were subjected to sham or burn injury and sacrificed at 1, 4, or 7 d after injury. Cytokine analysis by ELISA indicated increased serum IL-6, TNF-α, and MIP-2 24 h after injury. These levels returned to baseline by post-burn day (PBD) 7 (data not shown). Subsequent experiments were performed 7 d after the initial thermal injury in order to allow resolution of the initial inflammatory response prior to induction of the second hit with LPS.

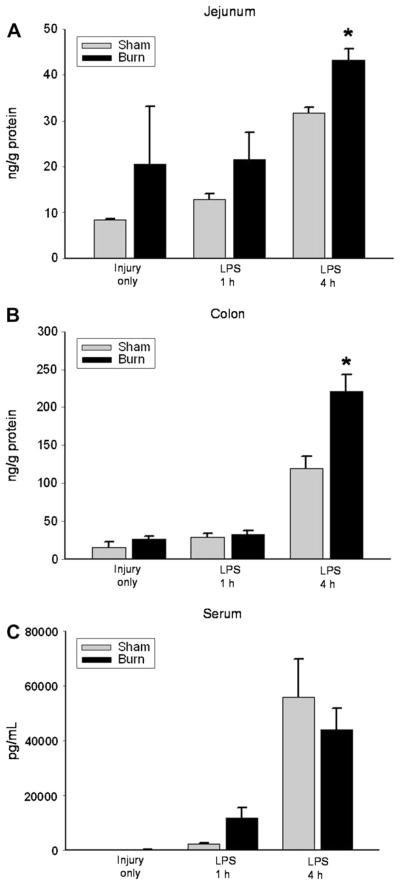

In order to determine the effect of thermal injury on the inflammatory response to a “second hit” of LPS, mice were exposed to either sham burn or thermal injury, allowed to recover for 7 d, and then treated with LPS. Sequential treatment with thermal injury followed by LPS resulted in significantly increased IL-6 production in jejunum and colon 4 h after LPS injection compared with mice that received sham injury followed by LPS injection (Fig. 1A and B). This pattern was not seen in serum samples, suggesting that these findings may be specific to intestinal mucosa at the time points examined (Fig. 1C). Prior sham injury did not alter the intestinal cytokine response to LPS compared with untreated mice (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

IL-6 levels on PBD7 in jejunum (A), colon (B), and serum (C) after injury alone and 1 and 4 h after LPS injection in sham (gray bar) and burn (black bar) injured mice. IL-6 levels in jejunum and colon were significantly elevated 4 h after LPS injection in burn compared with sham injured mice (*P < 0.05).

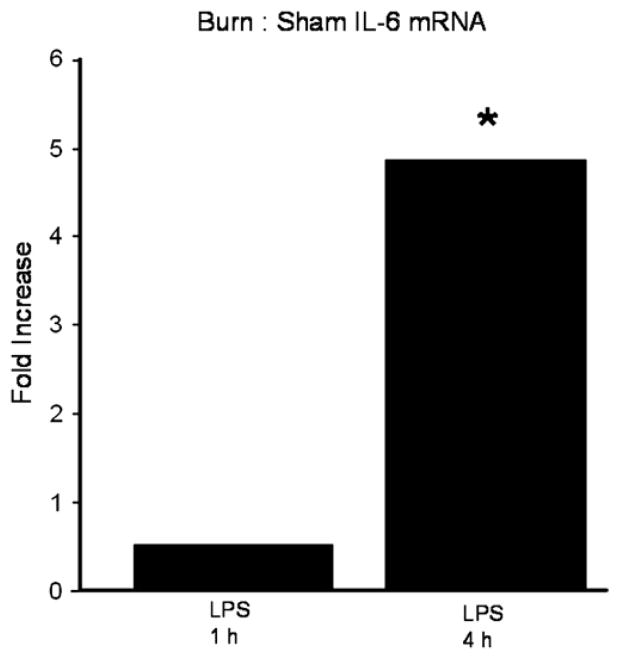

Increased IL-6 cytokine levels in jejunum and colon could be the result of either increased production or increased release of this cytokine. In order to determine if increased intestinal IL-6 protein levels potentially reflected transcription of the IL-6 gene, we analyzed jejunal mucosa for IL-6 mRNA levels. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) performed on jejunal samples from mice treated with either sham or thermal injury, then LPS, indicated significantly increased IL-6 mRNA levels 4 h after LPS injection in samples from mice treated initially with thermal injury compared with sham injury (Fig. 2). These data suggest that increased IL-6 protein levels in intestinal mucosa in response to a second hit may be the result of increased IL-6 production at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 2.

Jejunum IL-6 mRNA levels after treatment with sham or burn injury, recovery for 7 d, then injection with LPS. Data is expressed as fold difference in burn/sham mice 1 and 4 h after LPS injection (*P < 0.05).

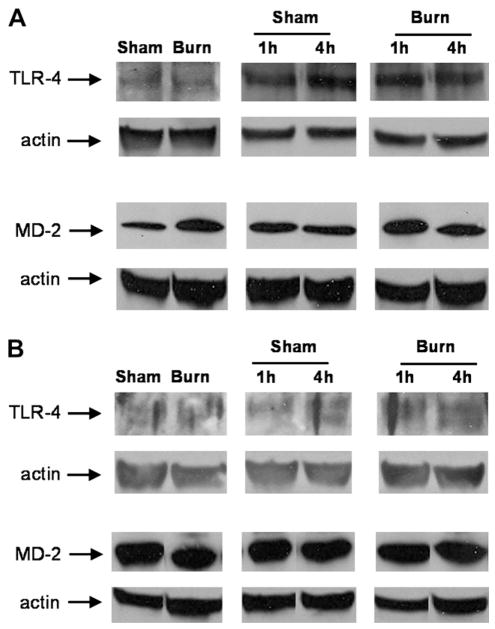

LPS-triggered signaling events are mediated, at least in part, via the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) pathway, resulting in activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors and downstream cytokine production [16, 17]. One potential mechanism for increased responsiveness of the intestine to LPS after remote thermal injury is an alteration in components of the TLR-4 receptor. TLR-4 binds LPS in conjunction with its co-receptor, MD-2. In order to determine if remote thermal injury altered TLR-4 and MD-2 receptor concentration, we performed Western blotting for these components. Tissue levels of TLR-4 and MD-2 were not altered by prior burn injury (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Representative jejunum (A) and colon (B) Western blots comparing sham to burn injured mice on PBD7 after injury alone and 1 and 4 h after LPS injection. Actin control demonstrates even protein loading. Paired comparisons were cut from the same Western blots.

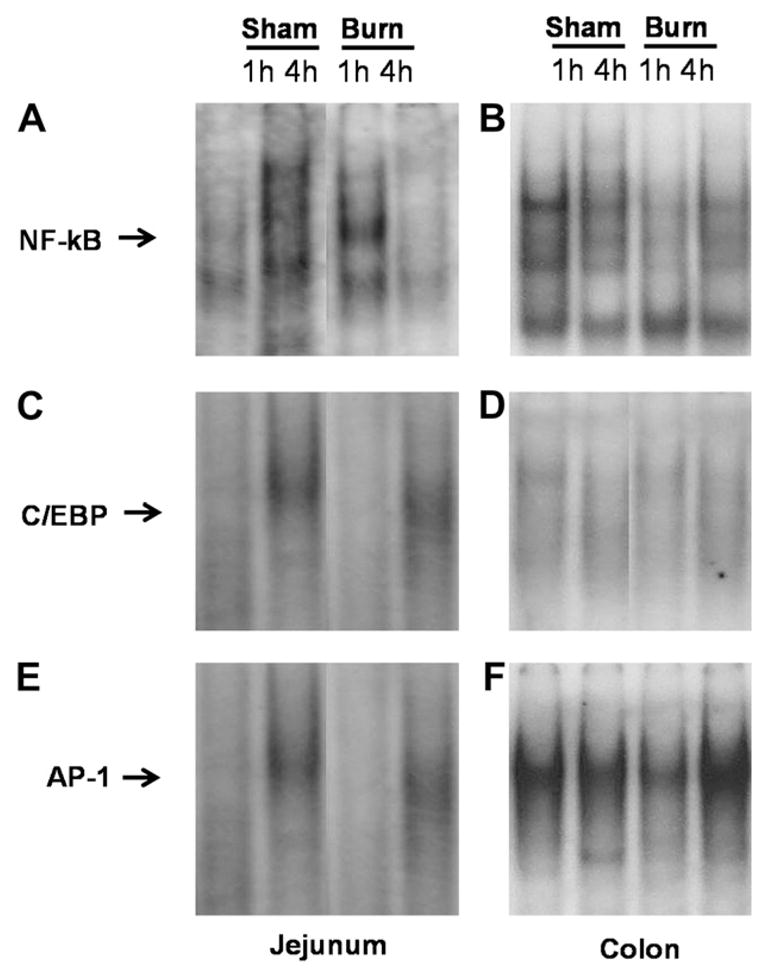

Transcription of the IL-6 gene is regulated by several transcription factors, including NF-κB, C/EBP, and AP-1. EMSA analysis for each of these transcription factors was performed on jejunal and colon samples from sham or burn injured mice treated with LPS. NF-κB DNA binding activity was less in mice with prior burn injury followed by LPS, compared with mice receiving prior sham treatment in colon at 1 h (Fig. 4A and B). No change was observed in C/EBP DNA binding activity between sham and burn groups (Fig. 4C and D). In jejunum, LPS increased AP-1 activation, but this was not affected by prior burn injury (Fig. 4E). However, EMSA analysis for AP-1 in the colon showed increased binding 4 h after LPS injection from mice treated with thermal injury compared with mice treated with sham injury (Fig. 4F). These data suggests that increased IL-6 in mice treated with thermal injury followed by LPS, may be the result of increased activation of the transcription factor AP-1.

FIG. 4.

Representative EMSA for NF-κB (A and B), C/EBP (C and D), or AP-1 (E and F) of nuclear extract samples from jejunum or colon of mice treated with sham or burn injury, allowed to recover for 7 d, then injected with LPS for 1 or 4 h. Paired comparisons were cut from the same EMSAs.

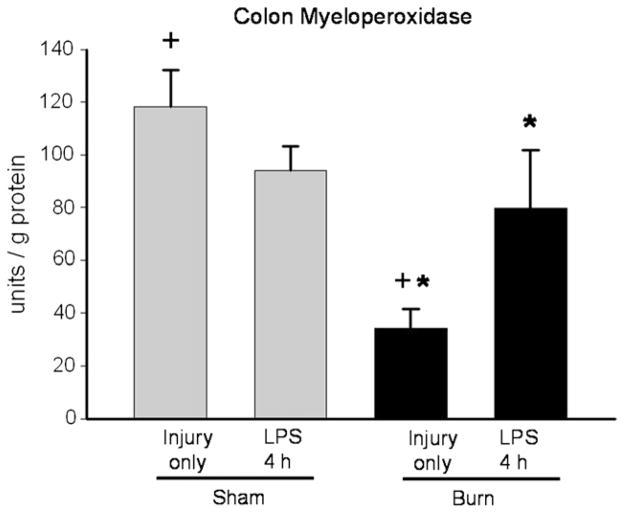

The intestinal mucosa is a complicated tissue containing multiple cell types. Leukocytes are one potential source for IL-6 production in this tissue. In order to determine the effect of prior thermal injury on leukocyte recruitment, we analyzed colonic segments for myeloperoxidase (MPO) content, a surrogate marker of tissue infiltration of neutrophils [18]. Seven days after thermal injury, MPO activity was decreased compared with samples from sham-treated mice (Fig. 5). This suggests that increased IL-6 production in intestine 4 h after LPS injection in mice treated with prior burn injury is not simply the result of increased neutrophil infiltration in the gut from the prior injury. Treatment of mice with LPS resulted in a significant increase in MPO activity in burn but not sham mice compared with baseline values (Fig. 5). These data suggest that prior thermal injury leads to increased inflammatory cell recruitment to the intestine during endotoxemia.

FIG. 5.

MPO assay of colon samples from sham (grey bars) or burn (black bars) injured mice on PBD7 after injury alone and 4 h after LPS injection (+P < 0.05 sham versus burn only); (*P < 0.05 burn versus burn + LPS groups).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the effect of prior thermal injury on the inflammatory response of the intestine to a systemic “second hit” of LPS. Our data have added to our understanding of the mechanism by which thermal injury leads to an exacerbated response to a “second hit” of LPS. These findings have important implications in the care of patients suffering from burn injury.

In initial experiments, we demonstrated that mice with a history of remote thermal injury respond to LPS with increased IL-6 production in both the small and large bowel. This finding is important, given the role that IL-6 plays in the inflammatory response to injury. Previous studies have indicated that IL-6 is essential for the increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation observed after ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice [19]. In these experiments, intestinal IL-6 increased 4 h after LPS injection, and was independent of serum IL-6 changes at this time point. Our findings indicate that LPS injection increased IL-6 mRNA levels in small bowel of mice subjected to remote thermal injury compared with mice with prior sham injury. Taken together, these findings suggest that IL-6 is produced locally, and is likely regulated at the transcriptional level. Our finding of augmented IL-6 production in the gut under these conditions expands on previous ex vivo experiments that demonstrated increased IL-6 production in enterocytes harvested from previously burned animals when these cells were exposed to LPS [11].

LPS-triggered signaling events are mediated primarily via the TLR-4 pathway, resulting in activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors and downstream cytokine production. In the present study, we examined the effect of thermal injury on TLR-4 expression. Analysis of intestinal levels of TLR-4 and its co-receptor MD-2 showed no consistent changes between thermal and sham injured mice on PBD7 or with LPS injection. These findings are consistent with recent work with a similar model reporting that inflammatory cells up-regulated TLR-4 early (3 d) after injury, followed by a decrease in TLR-4 expression late (14 d) after thermal injury [20]. Based on our data, altered IL-6 production in response to a second hit is not the result of differences in expression of components of the TLR-4 receptor.

IL-6 expression is regulated in part by the transcription factors NF-κB, C/EBP, and AP-1 [16, 17]. Individual analysis of DNA binding of these factors showed no consistent difference in mice with remote thermal injury compared with sham-injured mice 7 d after the initial insult. However, 4 h after LPS injection, only AP-1 binding was increased in the colon of those mice with remote thermal injury compared with sham. This suggests that augmented AP-1 binding in the intestine may be the mechanism for increased IL-6 gene expression in the intestine. Furthermore, our data suggest that prior thermal injury alters the colon to “prime” this tissue when it is subsequently challenged with LPS.

Leukocytes are one possible source of IL-6 production in this intestinal mucosa. During analysis of colon for myeloperoxidase (MPO) content, we found evidence of a marked reduction of leukocytes in colon of thermally injured mice. Others investigators using a similar thermal injury model in rats have shown that intestinal myeloperoxidase was significantly increased after burn, but these measurements were made early (3 and 24 h) after injury [21]. In the present study, burned mice had lower baseline intestinal MPO levels but appeared capable of dramatic leukocyte recruitment after LPS injection, while previously sham injured mice showed no increase in leukocyte content after LPS injection. These findings suggest that prior thermal injury may alter the immunological “tone” of the gut, leading to altered responses to a subsequent inflammatory challenge.

Because of its potential role in the pathogenesis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ failure (MOF), a greater understanding of the altered immunologic tone in the gut after burn injury may allow therapeutic intervention in patients at risk for the “second hit.” There is a growing body of literature suggesting that injury leads to enhanced LPS-mediated immune responses. Our data suggest that enhanced reactivity to LPS occurs in the intestine. This altered response is manifested by increased IL-6 production in intestinal tissue, and is regulated at the transcriptional level. An improved understanding of the mechanisms and clinical relevance of these changes in this important organ will augment our efforts to restore homeostasis after injury.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants no. 8902 (to TAP) and no. 8903 (to CKO) from the Shriners Hospitals for Children.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the 4th Annual Academic Surgical Congress, Fort Myers, Florida, February 2009.

References

- 1.Baue AE, Durham R, Faist E. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), multiple organ failure (MOF): Are we winning the battle? Shock. 1998;10:79. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris BH, Gelfand JA. The immune response to trauma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1995;4:77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saffle JR, Sullivan JJ, Tuohig GM, et al. Multiple organ failure in patients with thermal injury. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1673. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199311000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanucci SG, Gobara S, Santos CR, et al. Infections in a burn intensive care unit: Experience of 7 years. J Hosp Infect. 2003;53:6. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore FA, Moore EE. Evolving concepts in the pathogenesis of multiple organ failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:257. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rue LW, III, Cioffi WG, Mason AD, et al. The risk of pneumonia in thermally injured patients requiring ventilatory support. J Burn care Rehabilitation. 1995;16:262. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geyik MF, Aldemir M, Hosoblu S, et al. Epidemiology of burn unit infections in children. Am J Infect Control. 2003;31:342. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(02)48226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Xiao G, Yao Y, et al. The role of bifidobacteria in gut barrier function after thermal injury in rats. J Trauma. 2006;61:650. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196574.70614.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Xiao G, Yao Y, et al. The relationship between intestinal bifidobacteria and bacteria/endotoxin translocation in scalded rats. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2002;18:365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai X, Xiao G, Tian X. The relationship between postburn gene expression of modulators in gut associated lymph tissue and the change in IgA plasma cells. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2000;16:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogle CK, Mao JX, Wu JZ, et al. The 1994 Lindberg Award: The production of tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and prostaglandin E2 by isolated enterocytes and gut macrophages: Effect of lipopolysaccharide and thermal injury. J Burn Care Rehab. 1994;15:470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noel JG, Guo X, Wells-Byrum D, et al. Effect of thermal injury on splenic myelopoiesis. Shock. 2005;23:115. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000154239.00887.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritts TA, Wang Q, Sun X, et al. Induction of the stress response in vivo decreases nuclear factor-κB activity in jejunal mucosa of endotoxemic. Mice Arch Surg. 2000;135:860. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tung PH, Wang Q, Ogle CK, et al. Minimal increase in gutmucosal interleukin-6 during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:409. doi: 10.1007/s004649900692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schierwagen C, Bylund-Fellenius AC, Lundberg C. Improved method for quatification of tissue PMN accumulation measured by myeloperoxidase activity. J Pharmacol Methods. 1990;23:179. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(90)90061-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsusaka T, Fujikawa K, Nishio Y, et al. Transcription factors NF-IL6 and NF-κB synergistically activate transcription of the inflammatory cytokines, interleukin 6, and interleukin 8. PNAS. 1993;90:10193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dendorfer U, Oettgen P, Libermann TA. Multiple regulatory elements in the interleukin-6 gene mediate induction by prostaglandins, cyclic AMP, and lipopolysaccharide. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4443. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faith M, Sukumaran A, Pulimood AB, et al. How reliable an indicator of inflammation is myeloperoxidase activity? Clin Chim Acta. 2008;396:39623. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R, Han X, Uchiyama T, et al. IL-6 is essential for development of gut barrier dysfunction after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:621. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00177.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cairns BA, Barnes CM, Mlot S, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 ligation results in complex altered cytokine profiles early and late after burn injury. J Trauma. 2008;64:1069. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318166b7d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avalan D, Taskinlar H, Tamer L, et al. Protective effect of trapidil against oxidative organ damage in burn injury. Burns. 2005;31:859. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]