Abstract

While new empirical findings and theoretical frameworks provide insight into the interrelations between socioeconomic development, gender equity, and low fertility, puzzling exceptions and outliers in these findings call for a more all-encompassing framework to understand the interplay between these processes. We argue that the pace and onset of development are two important factors to be considered when analyzing gender equity and fertility. Within the developed world, “first-wave developers”—or countries that began socioeconomic development in the 19th/early 20th century – currently have much higher fertility levels than “late developers”. We lay out a novel theoretical approach to explain why this is the case and provide empirical evidence to support our argument. Our approach not only explains historical periods of low fertility but also sheds light on why there exists such large variance in fertility rates among today’s developed countries.

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between human development and fertility has recently received considerable attention, with some studies claiming that the established negative correlation between fertility and measures of human development, such as HDI, has fundamentally changed among the most advanced countries (Myrskylä et al. 2009; Harknett et al. 2014; Testa 2014; Luci-Greulich and Thévenon 2014). A limitation of this research, however, has been the relatively short-term focus, with analyses focusing on development and fertility trends beginning in the last decades of the 20th century. In this paper we argue that a more long-term perspective to this question is in order. Encompassing a broader time horizon beginning in the early 20th century, this paper therefore combines novel empirical evidence with a wide body of social science literature to provide new theoretical insights into the interrelations among low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. Specifically, we argue that the onset and long-term pace of socioeconomic development are inherently linked with a key driver of fertility variation within developed countries: differing gender equity regimes. Moreover, we argue that these gender equity regimes are not static, but instead, dynamic and closely tied to changes in fertility through a demographic feedback mechanism: a gender-equity dividend. This gender-equity dividend is the result of the following process: below-replacement fertility brought about by work-family conflicts yields age-structures at young adulthood that are characterized by a relative scarcity of women relative to men (given the prevailing gender-differences in the age at marriage), which in turn facilitates changes in gender-norms and the rise of greater gender-equity. Greater gender equity is then likely to help raise or stabilize fertility in low-fertility high-income countries. In this process, therefore, the emergence of below-replacement fertility implies a homeostatic mechanism that over the medium/long-term can contribute to increasing fertility, such as has been documented in some advanced countries with high levels of gender equity. We argue that this theory also helps explain the fertility pattern in countries such as S. Korea, where a rapid decline in fertility during the demographic transition has resulted in very low contemporary fertility levels associated with relatively high levels of household gender inequity. Moreover, given current age structures at young adult ages, we argue that changes in gender-norms should be imminent in such contexts, contributing to a reversal of the lowest-low fertility patterns. Drawing on these insights, we propose a variant of the demographic transition that incorporates an interplay between changes in fertility and gender equity.

BACKGROUND

Most country-level studies on the relationship between socioeconomic development and low fertility compare the development and fertility trajectories in high-income countries after the 2nd half of the 20th century. During this period, most high-income countries already had near or below replacement fertility. These studies therefore ignore the process through which low fertility initially emerged during the demographic transition. We argue that an understanding of the development-fertility interrelations requires a distinction based on the pace of development during the fertility transition. In first-wave developers, as we will argue below, socioeconomic development occurred more gradually during much of the late 19th and 20th century; in second-wave developers, in contrast, socioeconomic development was concentrated in the 2nd half of the 20th century, and economic growth rates were often significantly faster than those experienced by first-wave developers. In both cases, fertility decline was associated with the development process. And yet, despite both sets of countries attaining high income and generally low fertility levels, contemporary gender norms and levels of gender equity differ between first- and second-wave developers. These differences have far-reaching implications for current and future fertility trends and family dynamics, helping to explain why fertility has stabilized at moderately below-replacement levels in some, while dropping to very low and lowest-low fertility level in other countries. We develop this reasoning in more detail below.

First-Wave Developers

The late 19th to early 20th century was an era of profound economic, social, and demographic change for countries in Northern and Western Europe, as well as the English-speaking countries.2 Because these countries were at the forefront of industrialization and socioeconomic development, they are referred to hereinafter as “first-wave developers” (see Appendix I). Economic growth spurred a rise in living standards, educational and occupational opportunities for men and women flourished, and novelties like kitchen appliances and cars became available to a growing share of the population. While material change quickly swept across industrializing countries, societies found themselves in a flux of old and new ways of thinking. Traditional norms clashed with a new wave of progressive attitudes in several social domains. Observing these “clashes”, Ogburn (1922) theorized that a “maladjustment” period occurs during which individuals fail to synchronize behavior and attitudes to new material change. He called this delay between material and behavioral change a “cultural lag.” Ogburn’s emphasis on a cultural lag period is also reflected in the recently proposed theory of conjunctural action (TCA) (Johnson-Hank et al. 2011) to explain how fertility/family change arise through individual behaviors during periods of material change. In this TCA framework, for example, a cultural lag between material and behavioral change emerges because social action occurs in conjunctures, that is, short-term and contingent configurations of social structure. In such conjunctures, individuals employ familiar schemas and materials to make sense of what is happening. This framework emphasizes the importance of existing internalized schemas that act as prisms through which individuals make life decisions, such as having children. Because such schema are individually-learned and slow to change, the TCA framework argues that behavioral change is most likely to occur in contexts when schemas for different behavioral domains start to contradict each other: for example, when schemas regarding an increasing participation of women in the labor force start conflicting with schemas about fertility, childrearing and marriage. Because this conflict between schemas usually unfolds gradually over time, changes in schemas and the behaviors regulated by schemas, tend to follow changes in the social and institutional contexts with a cultural lag.

One area in which cultural lag was especially pronounced during the early 20th century was with respect to gender norms and women’s roles within the household, the economy and society. For example, technological progress and capital accumulation in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution complemented mentally intensive tasks more than physically intensive tasks, thereby raising the return to the former relative to the latter (Galor and Weil 1996; Galor 2011). Because women arguably had a comparative advantage in mentally intensive tasks requiring less physical strength, the demand for women’s labor increased as a result and the gender wage gap narrowed (Galor 2011). In similar vein, Goldin (1990) suggests that a greater demand for office and clerical work from information technologies propelled a surge in the demand for female labor. Moreover, the type of work women engaged in before and during the industrial revolution was transformed. Before industrialization, the economic participation of women largely occurred within a familial context (e.g., in agriculture or a family business), while during (and after) the industrial revolution, employment increasingly involved contractual agreements between employers and the individual (Ruggles 2015). The combination of women’s increasing labor force participation and the growing prevalence of employer-individual labor contracts strengthened women’s independence.

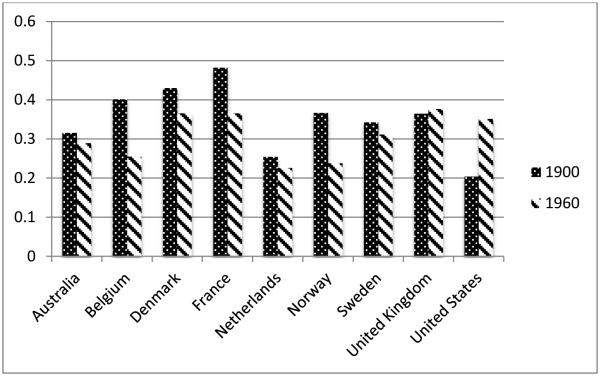

Occupational opportunities for women and female labor force participation clearly rose during the industrialization in first-wave developers during the early part of the 20th century. However, female labor force participation was often already widespread, ranging for example from 20% in the US to nearly 50% in France in 1900 (see Figure 1 below). In addition, there was a substantial extent of female economic activities on family farms and in family businesses (Ruggles 2015). Despite these relatively large levels of economic participation in the early 20th century, however, traditional male breadwinner/female housewife norms prevailed because women’s work often did not significantly increase their status or bargaining power, in part because family farms and businesses were often patriarchal in nature (Goldin 1990; Ruggles 2015). As a result, a substantial stigma against working wives outside the home existed at the time, leaving women with a “clear choice between family and career” (Goldin 2004, p. 23).

Figure 1. Female Labor Force Participation Rates for Select First-Wave Developers, 19003.

Source: Olivetti (2013)

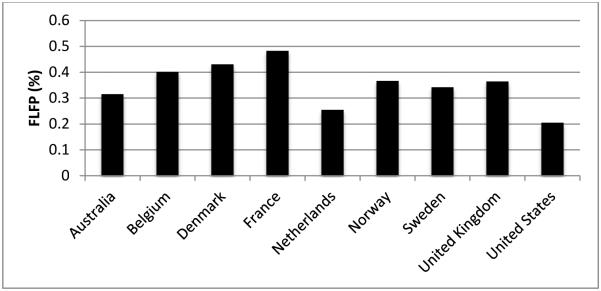

This observation about work-family conflicts in the early 20th century is important because a strong work-family conflict—or, in McDonald’s words “a conflict or inconsistency between high levels of gender equity in individual-oriented social institutions and sustained gender inequity in family-oriented social institutions” (McDonald 2000, p. 427)—contributes importantly to the rise and persistence of very low fertility in high-income countries.4 In other words, where traditional norms regarding childrearing, household work, and male breadwinner roles prevail while institutional gender equity and female labor force participation increases, women are more likely to view having a family as being at odds with pursuing career aspirations (hence, “work-family conflict”), and fertility falls to low levels.

Figure 2 illustrates how differential levels of institutional gender equity and household (or “family-oriented”) gender equity lead to varying degrees of the work-family conflict. The top-left quadrant echoes McDonald’s theory: high levels of both institutional and household gender equity concur with higher fertility than equally high institutional but lower household gender equity in the bottom-left quadrant. Expectedly, the bottom-right quadrant indicates that low institutional gender equity is associated with a weak work-family conflict. The top-right quadrant is left blank in Figure 2, as both empirically and theoretically, it is unlikely that men share household tasks evenly in a society where women do not (desire to) work outside of the home. The bottom-right quadrant may provide insight into the gender dynamics during the mid-century baby boom, an aspect on which we elaborate in our concluding discussion.

Figure 2.

Female Labor Force Participation and Household Gender Equity Relationship

While McDonald’s theory of gender equity and fertility was developed for contemporary high-income countries within the post-baby boom context, it is also applicable to the social and demographic context of the early 20th century. In particular, several recent studies have argued that one consequence of the work-family conflict during the early 20th century was sub-replacement fertility (Van Bavel 2010; Tolnay and Guest 1982).5 But this attribution of low fertility during the first part of the 20th century to work-family conflict is not necessarily a new insight. Many social scientists of the early 20th century, including Edin (1932), Myrdal (1941), Tandler (1927), Charles (1934), Darwin (1919), von Ungern-Sternberg (1937), and Wieth-Knudsen (1937), all came to a similar conclusion and directly discussed the negative associations between fertility and female educational attainment/labor market participation, speculating about the causal link between the two.6 In Sweden, a country now championed for its family friendly environment, both contemporary and current scholars have argued that very low fertility was driven partly by female laborers who found it difficult to combine childcare with a career (Van Bavel 2010; Edin 1932). In the United States and Australia, nearly half of female university graduates in the early 20th century remained childless, while the other half reached fertility levels well below replacement (Cookingham 1984; Mackinnon 1993; Goldin 2004). High incidences of childlessness among working women were also documented in England and Wales (Kelsall and Mitchell 1959) and Germany (von Ungern-Sternberg 1938). As Van Bavel and Kok (2010) observe: “for well-educated women in the early twentieth century, to become a mother often meant forfeiting a career.”7

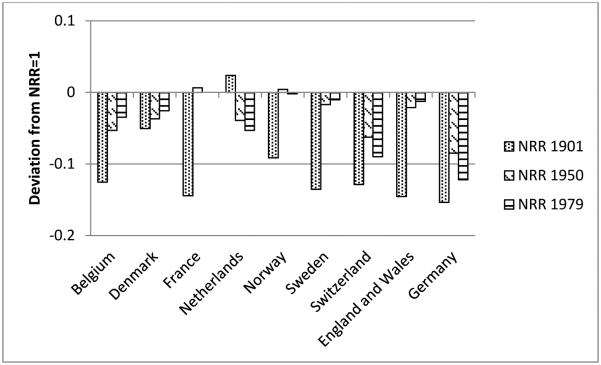

It was during this time of apparently strong family-work conflicts in the early 20th century when fertility fell substantially and population replacement levels in many first-wave developers hit their all-time lows. Figrue 3 compares net reproduction trends for select Northern/Western European countries, and shows that reproduction nadirs, that is, a long-term trough in fertility rates, occurred in the early 20th century, and that the indicator of generational reproduction, the cohort NRR, has risen, in some cases substantially, over the latter half of the 20th century. 8

Figure 3. Deviation from Cohort NRR=1 in select First-Wave Developers, 1901, 1950, and 1979 Cohorts.

Source: Sardon (1991) for early 20th century cohort fertility data and Myrskylä et al. (2012) for late 20th century data9. Due to data constraints, Cohort NRR for Belgium and Germany in the first column represent 1906 and 1905, respectively.

While comparable cohort NRR data for the United States and Australia are not available, other indicators suggest that similarly rapid declines in fertility were taking place. For instance, period NRRs in the mid-1930s in both countries attained below the replacement rate (Van Bavel 2010), and in economically progressive areas, childlessness levels rose to unprecedentedly high levels (approaching 30% in the northeastern US and 25-30% in Australia) (Morgan 1991; Rowland 2007).

As the 20th century progressed, gender roles in first-wave developers became more egalitarian. Hence, while the first forty years of the early 20th century in Western/Northern Europe and the English-speaking countries were dominated by rigid gender roles and a strong work-family conflict, the latter half was characterized by a departure from these traditional gender norms, a trend towards more gender equity both within the family and in the labor market, and a greater prevalence of dual-career households.

This enormous transformation over several decades is measureable using data on the relative and absolute division of household labor. Using time-budget surveys for the UK and the US, Gershuny and Robinson (1988) for example showed that women’s participation in household work declined substantially from the 1960s to 1980s, while men’s participation increased (though remained much less than that of women). Their findings closely paralleled similar findings for other first-wave developers, like Canada, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway, indicating fairly widespread progress during this time period toward a more egalitarian division of household labor in among first-wave developers. There are some current high-income countries, such as Japan and Korea, that continue to have a less egalitarian division of household labor; but these countries are second-wave developers, and this lagging behind in gender-equity is predicted by our theory. Moreover, it should be noted that these macro-level observations do not capture significant heterogeneity in gender equity change. It has been well-documented that behavioral and attitudinal changes first emerged among the highly educated before diffusing to other educational and socioeconomic groups (Bianchi et al. 2000).

Nearly 12 years later, Bianchi et al. (2000) found the trend toward household gender equity had continued so much so that household work had nearly been cut in half for women in the US since 1965, and doubled for men during this period. An international comparison of unpaid work trends by Hook (2006) revealed similar optimistic results: over-time increases in unpaid work by men in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and the UK. Other recent studies have found similar longitudinal advances in household gender equity throughout Western countries (e.g., Sullivan and Coltrane 2008; Bianchi et al. 2007). Lastly, a comparison of OECD countries shows that by and large, Northern/Western European and English-speaking countries have the smallest gap in the number of minutes women and men perform in unpaid work, while East Asian and Southern/Eastern European countries have the largest (Miranda 2011).

Inequalities persist with regards to both the “quality” and “quantity” of household labor in “first-wave developers”: women continue to bear most of the burden in the number of minutes spent on household labor, and the type of unpaid work performed by each gender varies (with men taking on more “masculine” tasks like yard work and home repair, and women more “feminine” tasks like cooking and cleaning) (Bianchi et al. 2007; England 2010; Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard 2010). Yet despite persisting inequalities, it is impressive how much these disparities have shrunk over such a short time horizon. As Sullivan and Coltrane (2008) optimistically describe, “men and women may not be fully equal yet, but the rules of the game have been profoundly and irreversibly changed…[a]ll these trends are likely to continue for the foreseeable future.”

It is worth noting that the aforementioned changes in household gender norms have contributed to shaping distinct work-family relationships across cohorts. This is particularly well documented for the United States, given the availability of detailed cohort studies, but we believe that these changes have occurred broadly similar in other first-wave developers. Specifically, in a seminal study of the evolution of the work-family conflict over the 20th century, Goldin (2004) traces the career and family experiences of five cohorts of college-educated women in the United States. The work-family paths identified by Goldin include: “family or career” (Cohort 1, graduated 1900-1919), “job then family” (Cohort 2, graduated 1920-1945), “family then job” (Cohort 3, graduated 1946-1965), “career then family” (Cohort 4, graduated 1966-1979), and finally, “career and family” (Cohort 5, graduated 1980-1990). Goldin’s concludes that “[e]ach [generation] stepped into a society and a labor market with loosened constraints and shifting barriers. The road was not only long, but it has also been winding…only recently has a substantial group been able to grasp both [work and family] at the same time” (Goldin 2004, p. 34; italics not in original).10

GENDER-EQUITY DIVIDEND

Our discussion above highlighted that trends towards gender equity, and divergences in the pace of such trends across countries, are central to understanding contemporary fertility patterns and their cross-country variation. Yet, despite this centrality, the determinants of movements towards gender equity (or the lack thereof) continue to be somewhat poorly understood. A large body of literature stresses social, political, and economic explanations (such as the second-wave Feminist movement, structural changes in the labor market, the introduction of the pill, and the implementation of family friendly policies) as drivers of the great gender equity advances which began in the 1960s/1970s in many first-wave developers (see, for example, Esping-Andersen 2009; Bianchi et al. 2000; Bianchi et al. 2007; Sullivan and Coltrane 2008; Goldin 1990). Adding to these existing explanations, we propose a novel demographic explanation. Specifically, we believe that these changes towards gender equity during the 2nd half of the 20th century were facilitated by an age structure that fosters greater marital bargaining power for women.

In a related literature, the “demographic dividend” refers to a period during which a country’s age structure provides infrastructure for economic growth (Bloom et al. 2003). According to this theory, a bulge of working age cohorts allows for high productivity while smaller older and younger cohorts minimize dependency ratios. Few scholars would argue that the “demographic dividend” is a primary driver of economic development. Instead, the demographic dividend refers to a favorable population age structure that can facilitate socioeconomic development by increasing savings, human capital investments and female labor force participation.

Paralleling this logic of a favorable age distribution for economic development, we argue that there also exists a population age distribution that facilitates advances in gender equity via greater spousal bargaining power as a result of changes in the “relative scarcity” of women in the marriage market. A marriage squeeze occurs when eligible females outnumber eligible males or vice-versa (Schoen 1983). While often discussed as a phenomenon in the African American community where local sex-ratios are often distorted due to high rates of incarceration and mortality among marriage-age black men, a marriage squeeze can also occur at the population level as a delayed consequence of rapid fertility declines and the resulting subsequent changes in the population age structure at young adult ages.

Theoretically, when the supply of females is greater than that of males, females experience greater competition in the marriage market amongst themselves and lose bargaining power in potential marriages (Guttentag and Secord 1983; Angrist 2002). After all, a man who wishes to marry a “traditional” or homemaker wife has better chances to do so when he has more women from which to choose. The opposite should hold true when males are in a marriage squeeze: they face greater competition in the marriage market and therefore, to succeed in the marriage market, men must be willing to “pay a higher price” for a potential spouse (Guttentag and Secord 1983; Angrist 2002). Greater gender equity within the household is one aspect through which this “higher price” is likely to be reflected. Specifically, for women, a larger pool of men translates into more easily finding men with desirable characteristics, including men who are more supportive of equitable gender ideologies. Individuals may not make conscious decisions based on knowledge of skewed sex ratios; however, this is not important. As Guttentag and Secord explain:

It is not a matter of directly perceiving the sex ratio. Rather, as a result of continuing experiences in encounters with the opposite sex, the average individual whose gender is in the minority occasionally has more alternatives in terms of actual or potential partners, whereas the opposite sex has fewer such alternatives. From time to time, this produces a one-up, one-down situation that leads the party whose gender is in the minority to have higher expectations for outcomes in an existing relationship and less willingness to commit oneself, while the individual of the opposite sex feels a greater dependency on the existing relationship and is willing to give more. When the sex ratio is considerably out of balance, the widespread effects increase the visibility of desirable alternatives for the scarce gender, and the injustices and exploitations undergone by the gender in oversupply become more salient.” (1983:162)

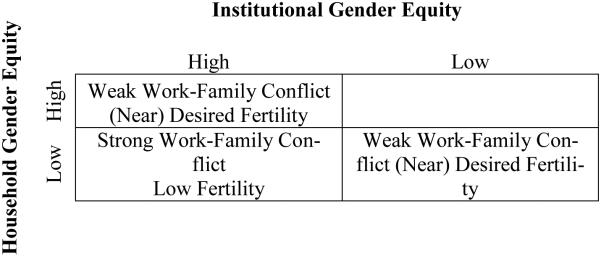

We illustrate the effects of this marriage squeeze in two scenarios:

Scenario 1

Imagine a population closed to migration in which the NRR for time t-40 to t-20 is 1.65, yielding an annual intrinsic growth rate of 2% during this period (Figure 4a). Because men marry, on average, at older ages than women (Van Bavel 2012; Heer and Grossbard-Shechtman 1981; Angrist 2002), the age distribution in this growing marriage market in this population (ages 20-40) makes it advantageous for older men to search for younger women, as the supply of younger female cohorts is greater than that of older male cohorts.

Figure 4a and 4b. Growing and Shrinking 20-40 Year Old Marriageable Populations.

Now imagine the reverse scenario: a population closed to migration has an annual NRR of .60 during time t-40 to t-20 and an intrinsic growth rate of −2%, rendering each successive birth cohort smaller than the previous, like in Figure 4b. If women continue to marry somewhat older men, as has empirically been the case even during periods of a marriage squeeze, females in each birth cohort have a larger supply of men from which to choose.

We argue that the age-structure implications of the sub-replacement fertility levels (i.e., NRRs<1) experienced in the early 20th century by first-wave developers played a role in advancing gender equity at young adult ages during the mid to late half of the century. Specifically, low fertility in the early 20th century resulted in mid-20th century age structures that largely resembled scenario 2 around primary marriage and childbearing ages: cohorts of older males in the 20-40 marriage market outnumbered younger cohorts of females. These age structures coincided with a period of rising female labor force participation as well as an emergence of quantifiable changes in gender norms. In our opinion, this co-occurrence was not a coincidence. Instead, that a gender-equity dividend has occurred as a result of the age-structure at young adult ages that implied a relative scarcity of women relative to men given the prevailing age-difference between (potential) spouses. Specifically, early 20th century periods of low fertility, brought on in part from a strong work-family conflict and low household gender equity at the time (see above), created an age structure conducive to increasing bargaining power of women and increasing household gender equity. In turn, these gains in household gender equity weakened the work-family conflict and thus contributed to a stabilization of fertility declines or even an increase in fertility in subsequent years.11 Emphasizing this interrelationship is important, as it illustrates a homeostatic relationship of bi-directional causality between fertility and gender equity: low (household) gender equity causes persistent low fertility, and through its effect on the population age structure, with some delay, low fertility (and time) facilitates gender equity change by affecting male-female bargaining power within the household. We refer to this latter effect as the gender-equity dividend. But similar to the demographic dividend, the benefits of this gender-equity dividend do occur not automatically or necessarily unfold at the same pace; institutional factors, such as flexibility of labor markets, institutional restrictions to the expansion of day care, or tax disincentives for dual career couples can slow down and/or limit the unfolding of the gender-equity dividend, just as the demographic dividend can be reduced by unfavorable institutional frameworks.

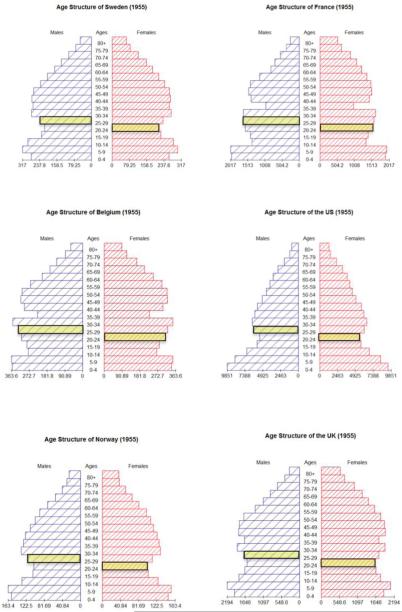

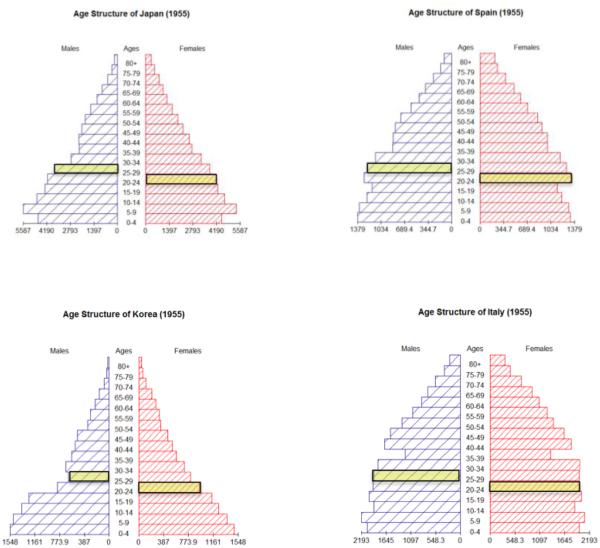

To support the connection between age structure and gender-norm changes that are postulated to occur as part of our theory, the population pyramids in Figure 5 illustrate the existence of the gender-equity dividend in select first-wave developers in 1955. All of these countries are characterized by a relative scarcity of women as compared to men at marriage and primary childbearing ages given the prevailing age-difference between spouses. In contrast, the population pyramids in Figure 6 show the age structure for select second-wave developers in that same year, none of which have an age structure that would be conducive to a gender-equity dividend. Consistent with our theory of the effect of a marriage squeeze on subsequent trends towards gender equity, the different age-patterns for first-wave developers (Figures 5) and second-wave developers (Figure 6) align with the higher levels of gender equity in the former as compared to the latter countries.

Figure 5. Population Age Structures in Select First-Wave Developers (1955).

Figure 6. Population Age Structures in Select Second-Wave Developers (1955).

Because the mean age of marriage in first-wave developers in the mid-century was around 25 for men and 22 for women (as indicated in Table 1 and 2 below), the “gender-equity dividend” would have largely begun with marriage market imbalances between 1950-1960. Yet the increased bargaining power engendered by declining subsequent cohorts does not stop at marriage: a heightened “threat point of divorce” favorable to women presumably followed these cohorts over time. In other words, the male cohorts involved in the gender-equity dividend faced an unfavorable re-marriage market over their primary adult ages, during which decisions about fertility and childrearing are made.

Table 1.

Ratio Males (25-30)/Females(20-25) and Mean Age at Marriage by Sex (1955) in First-Wave Developers

| Country | Males 25-30 (thousands) |

Females 20-25 (thousands) |

Males (25- 30)/Females(20-25) |

Mean Age At Marriage (Males) |

Mean Age At Marriage (Females) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 236 | 212 | 1.11 | 26.20 | 23.20 |

| France | 1,633 | 1,539 | 1.06 | 25.30 | 22.50 |

| US | 6,108 | 5,582 | 1.09 | 23.30 | 20.60 |

| Belgium | 328 | 311 | 1.05 | 24.80 | 22.00 |

| Norway | 117 | 101 | 1.17 | 25.60 | 22.20 |

| UK | 1,700 | 1,629 | 1.04 | 24.80 | 21.80 |

Notes: Due to data unavailability for 1955, mean age at marriage represents values in 1960.

Table 2.

Ratio Males (25-30)/Females (20-25) and Mean Age At Marriage By Sex (1955) in Second-Wave Developers

| Country | Males 25-30 (thousands) |

Females 20-25 (thousands) |

Males (25- 30)/Females(20-25) |

Mean Age At Marriage (Males) |

Mean Age At Marriage (Females) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 1,240 | 1,327 | 0.93 | 27.90 | 24.70 |

| Italy | 1,912 | 1,964 | 0.97 | 28.50 | 24.70 |

| Japan | 3,723 | 4,170 | 0.89 | 27.30 | 24.70 |

| Korea | 635 | 946 | 0.67 | 25.20 | 21.30 |

Notes: Due to data unavailability for 1955, mean age at marriage represents values in 1960.

Tables 1 and 2 provide the mean age at first marriage for men and women in all the countries examined, as well as attempts to quantifiably capture the gender-equity dividend. We note that, on average, men marry women 3 years younger than them. Dividing the number of females aged 20-25 by the number of males aged 25-30 provides numeric support that older males outnumbered younger females in first-wave developers but not in second-wave developers in the mid-20th century. Theoretically, these age structures provided the demographic infrastructure for first-wave developers to make strides in creating advances in household gender equity.

Two important points regarding the gender-equity dividend should be emphasized.

First, when stating our key assumption to the gender-equity dividend – that men marry at older ages than women – an intuitive question arises: why don’t men match with women closer to their age if they face a scarcity of younger women? The mid-century marriage squeeze did indeed correspond to shifts in marriage timing (e.g., between 1951 and 1978, mean age at marriage for American men decreased .54 years and increased .53 for American women), though these shifts were symmetric for men and women and fairly modest in magnitude, and thus did not eliminate the marriage squeeze. This limited ability to reduce the marriage squeeze by adjusting the gender-gap in the age at marriage is likely due to the fact that cohort size composition among individuals aged 20-40 took place abruptly in the 1950s (i.e., the marriage squeeze did not sprout up gradually, but rather, quickly). Thus, when the marriage squeeze began, women of similar age to men were likely married, and men therefore had to marry downward in age. For a new equilibrium in the mean age of marriage for men and women to emerge, the marriage squeeze would necessarily need to occur over longer periods of time (and marriage squeezes in Asia as a result of distorted sex ratios may be an example for this process; see Guilmoto 2012).

And second, it is important to emphasize that the benefits of the gender-equity dividend are unlikely to be reaped in the absence of institutional, cultural, and economic factors that promote greater gender equity. These factors, including rises in female labor force participation, gender equity oriented policies, and cultural shifts in women’s rights are arguably the most important catalysts to changes in gender equity attitudes/behaviors, whereas the gender-equity dividend is simply a facilitator of these changes.

There has been a fragmented discussion in the literature supporting the idea that population age structures exerted catalytic pressure on gender norms in first-wave developers. In Sweden, for example, Kabeer (2007) and Florin and Nilsson (1999) argue that sustained low fertility throughout the early 20th century and rapid economic growth led to labor shortages in the 1960s. Kabeer (2007, p. 249) asserts that the small nation of about 7.5 million had “a choice between encouraging immigration or persuading [more] women to increase their labor force participation”. Gender advocates, backed by Sweden’s strong labor unions, supported the latter position, prompting political parties to incorporate the ideals of gender equity in their platforms (Sandqvist 1992; Florin and Nilsson 1999; Kabeer 2007). “Getting mom a job and making dad pregnant”, as put by one young parliamentarian in the 1970s , encapsulates the direction in which Swedish society wished to move (Klinth 2002). A string of policies and initiatives were to follow in order to get men and fathers more involved in family life and women more involved in the labor market (Nagy 2008; Klinth 2008).

A similar story unfolded in the United States. Decades of low immigration due to the restrictive “Johnson-Reed Act” combined with low levels of fertility from the 20s through early 1940s gave rise to a marriage squeeze for men—that is, an age structure favorable to women in the marriage market (see Figure 5 above). Heer and Grossbard-Shechtman (1981, p. 62) contend that “the marriage squeeze [of the 1950s and 60s] was instrumental in reducing not only the proportion of females who could marry but also the compensation which men were obliged to give women for traditional wifely and maternal duties”.

FERTILITY AND GENDER EQUITY IN SECOND-WAVE DEVELOPERS

Whereas Northern/Western European and the English-speaking countries experienced rapid industrialization in the mid-19th/early 20th century, second-wave developers constitute a group of countries that have experienced sustained large increases in living standards and development primarily from the mid-20th century onwards. Second-wave developers include countries in Southern Europe, East Asia, and to an arguable extent, Eastern Europe. While a characterization of second-wave developers based on the timing of industrialization is sufficient for our purposes, indicators such as GDP growth rates and historical human development index (HDI) figures can be used to confirm the grouping of these countries as “second-wave developers” (see Appendix I; see also, Crafts 2002, Maddison 2007, and Galor and Moav 2004).

While institutional gender equity (in labor market and educational opportunities) has increased in second-wave developers over the last half-century, often at very rapid pace, it has been widely documented that family-oriented gender equity in these 2nd-wave developers lagged behind those in the 1st wave developers (Esping-Andersen 2009). And the differences in household gender equity measures between first and second-wave developers remain substantial to date. For example, in second-wave developers like Italy, Portugal, Japan, and Korea, women perform a daily average of three to four hours more of unpaid work (i.e., household tasks) than men; in first-wave developers like Denmark, Sweden, the USA, and Belgium, this figure lies within one to two hours (Miranda 2011).12 Furthermore, strong family values that stress marriage, discourage cohabitation, and encourage traditional breadwinner norms persist across second-wave developers (Reher 1998; Anderson and Kohler 2013).

Differences in fertility trends between first and second-wave developers have also been salient. While cohort fertility levels in most first-wave developers remained relatively stable from 1950-197913, they have fallen—in many cases substantially—over the same period in second-wave developers (Myrskylä et al. 2013). Furthermore, very low period TFRs (between 1.0-1.4 children per woman) over the last two decades have been documented almost exclusively in second-wave developers (Kohler et al. 2002; Goldstein et al. 2009). Many studies argue that fertility differentials between countries that we classify as first-wave and second-wave developers are driven in large part because of a strong-work family conflict in second-wave developers (e.g., Myrskylä et al. 2013; McDonald 2013; Esping-Andersen 2009).

While the gap between institutional and family-oriented gender equity remains large in second-wave developers, there is evidence that some second-wave developers are entering an incipient stage of change regarding gender norms and family values similar to what first-wave developers underwent in the 1970s. For instance, Rindfuss et al. (2004, p. 843) make a compelling case that “major changes in Japan have converged to create conditions favorable for dramatic family change”.14 Their conclusion stems from mounting tensions between traditional family expectations and changes in the labor market, educational system, consumer preferences, and women’s desires for greater gender equity in marriage. Similar findings of the nascent breakdown of traditional family norms have been observed in other second-wave developers, like Spain, where “[y]oung parents behave increasingly like Americans when it comes to who reads with the children and who washes the dishes” (Esping-Andersen 2009, p. 173). While too early to make definitive claims, second-wave developers may soon be following first-wave developers in adopting a more equitable gender regime.

THEORY

In light of the aforesaid historical and contemporary trends, we postulate that countries attain very low fertility rates following periods of fast-paced socioeconomic development. During this period, rapid gains in institutional gender equity are made while family gender equity lags; in other words, women’s access to education and employment increases rapidly while family/household norms remain unchanged or change only gradually. This period of incoherent levels of gender equity in individually oriented social institutions and family-oriented social institutions leads to a “work-family conflict” for career-oriented women (e.g., McDonald 2013; Bellavia and Frone 2005; Schreffler et al. 2010). As a result of this disequilibrium in gender equity, a period of low fertility emerges and persists, often lasting several decades. With some delay, the low fertility resulting from these work-family conflicts can subsequently facilitate changes toward greater gender equity through a gender-equity dividend that results in a relative scarcity of women relative to men as a result of the age-structure at young-adult ages. Indicators of familial gender norms becoming more equitable include greater participation by males in household and childrearing tasks, and attitudinal shifts supporting dual-earning partnerships. These changes are facilitated by favorable social, demographic, and economic factors, which, similar to the demographic dividend in relation to economic development, open a window of opportunity for advances in household gender equity.

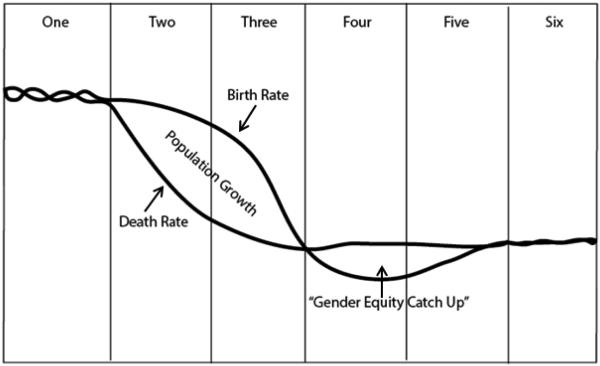

Our theoretical framework can be directly incorporated as part of the demographic transition (see Figure 7). In Phase 4, fertility drops to sub-replacement levels, in part due to an incongruence between traditional family gender equity and modern institutional gender equity that results in a substantial work-family conflict. Over time, family-oriented gender equity “catches up” to institutional gender equity as a consequence of institutional, societal, cultural, economic, and—as we introduce in this paper —demographic changes, effectively weakening the work-family conflict. As a result, having both a career and family becomes more compatible, leading to less voluntary childlessness and relatively higher fertility rates. If one were to place developed countries in the transition in Figure 7, Western/Northern European and English-speaking countries, the forerunners of the demographic transition and industrialization, would fall roughly in Phase 5. Southern Europe and East Asian countries, most of which began developing in the 20th century, would fall in Phase 4 of the transition. With a weak work-family conflict and near-replacement fertility, Sweden and Denmark are arguably the closest countries to reach Phase 6. Ironically, these two countries were cited by Van de Kaa (1987, p. 11) as the frontrunners of the Second Demographic Transition —a theory that presumes long-term sub-replacement fertility (Lesthaeghe 2010).15

Figure 7. Extended Demographic Transition.

We should point out that in Phase 6 a convergence between actual and desired fertility levels occurs —not necessarily a return to replacement level. Nonetheless, the Figure is drawn under the assumption that desired fertility levels roughly equate to replacement level fertility, as desired fertility in nearly all developed countries hovers around 2-2.2 children per woman (Sobotka and Beaujouan 2014).

EMPIRICAL SUPPORT

Our theoretical framework integrates well with recent empirical analyses that have started to re-evaluate the relationship between socioeconomic development and fertility. Bongaarts and Watkins (1996), for example, use the Human Development Index (HDI) and show a strong linear negative fertility-development association. More recently, Myrskylä et al. (2009) demonstrated the emergence of a J-curve relationship between fertility and HDI, suggesting that very advanced levels of socioeconomic development may cause fertility decline reversals., Several recent studies have investigated this in more detail using both micro and macro data, and despite some criticisms of Myrskylä et al.’s (2009) findings (e.g., Harttgen and Vollmer 2014; Furuoka 2009), there is increasing empirical and theoretical support that the relationship between development and fertility has fundamentally changed in recent decades among the most developed countries (e.g., Harknett et al 2014; Testa 2014; and Luci-Greulich and Thévenon 2014).

Deviating somewhat from the above literature on the J-curve relationship between fertility and HDI, we argue in this paper that the – in historical comparison small – changes in recent development per se are not driving the reversal in fertility declines. Instead, within our long-term perspective, we argue that relatively high and stable fertility levels are prevalent in countries that began developing in the 19th/early 20th century (e.g., Norway, the USA, the Netherlands, Australia, Sweden, etc.).16 Specifically, consistent with the theory outlined here, thanks to greater gender equity that has emerged in these 1st wave developers as a result of the gender-equity dividend in the second half of the 20th century, it has become more feasible for women to balance a work and family life. As a result of this head-start in development, these countries also tend to be ranked highly at or near the top of development indices such as the HDI. Nevertheless, their relatively high fertility levels are not due to simply achieving a certain threshold of development. Instead, the relatively high current fertility is rather due to having established a society in which evolved familial norms have made work and family more compatible, an accomplishment that was in part facilitated by the gender-equity dividend occurring earlier in the 20th century.

Emphasizing this mechanism leading to gender equity, our theory therefore can reconcile the “puzzles” such as S. Korea and Japan in Myrskylä et al.’s (2009) J-shape relation between fertility and development. Specifically, while they have quickly caught up in literacy, life expectancy, and wealth over the last 50 years, second-wave developers with comparable HDI levels as second-wave developers (e.g., Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong) are outliers to the J-curve relationship because persisting low gender equity drives fertility to very low levels.17 These countries have (not yet) benefitted from the gender-equity dividend. Thus, even as the East Asian or Southern/Eastern European countries attain higher HDI levels, it seems unlikely to us that fertility (and specifically, the quantum of fertility) would rebound significantly to higher levels without changes in gender regimes. But they are likely to do so in the future.

As Goldin (2004) rightfully points out, only recently has the possibility of combining a job and family become widespread throughout all income and educational strata in the United States.18 We must continually remind ourselves that it took more than a century from the onset of industrialization for this process to occur, and for the attitudinal, institutional, and economic groundwork to be laid to facilitate the balance of work and family in first-wave developers (and even among first-wave developers, the balance of work and family is often still challenging). From this logic, it becomes clear that time has served as a crucial ingredient for lagging household gender equity to catch up with institutional gender equity. This is consistent with the cultural lag theory (Ogburn 1922), as well as recent theoretical developments that emphasize slowly-changing schemas as major determinants of fertility change (Johnson-Hanks et al., 2011). On the surface, therefore, a simple explanation for why second-wave developers face a strong work-family conflict is that second-wave developers have simply not had enough time for family-oriented gender equity to catch up to institutional oriented gender equity. On a deeper level, this lag in fertility response is related to the change of underlying norms, schemas, and institutions, which respond gradually and only with delay to changes in educational and occupational opportunities for women.

Thus, we hypothesize that the prevailing traditionalism regarding family norms, sex roles, and gender equity in Southern/Eastern Europe and East Asia is partly attributable to the fact that the onset of rapid socioeconomic development in these countries occurred much later than the first-wave developers, and that the pace of development occurred at such a fast rate that household gender equity started to lag behind, resulting in a mismatch between institutional and household gender equity in many 2nd wave developers that often persists until today. Given the close connection between low gender equity and low fertility, the fast pace and late onset of development contribute to second-wave developers’ low fertility rates via low gender equity. A corollary of this finding for comparative cross-country studies is that the pace of development should be a predictor of how low fertility drops towards the end of the fertility transition.

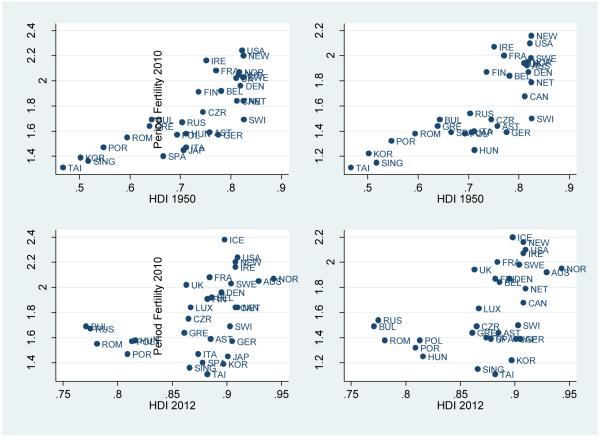

HDI figures for 1950 plotted against 2010 period fertility and completed fertility for the 1979 cohort lend support to our hypothesis: the most developed countries in the mid-20th century—all first-wave developers—have, on average, substantially higher fertility than second-wave developers. Among all developed countries, HDI figures for 2012 explain only about 18% of completed cohort fertility variation (for the 1979 birth cohort) and 22% of 2010 period fertility variation (see Figure 8). Remarkably, HDI estimates for the same countries in 1950 are much better predictors of today’s fertility trends, explaining about 60% of current variation in both period and cohort fertility. While the graphs say nothing about family policies, gender equity, or labor market flexibility, the 1950 HDI figures suggest that the pace and the onset of development, are much more explanatory of current fertility trends than present-day development levels.19

Figure 8. Top Left-Cohort Fertility (1979) on HDI 1950; Top Right-Period Fertility (2010) on HDI 1950; Bottom Left-Cohort Fertility (1979) on HDI 2012; Bottom Right-Period Fertility (2010) on HDI 2012.

Source: 1950 HDI estimates from Crafts (2002) and 1979 Cohort Fertility values from Myrskylä et al. (2012)

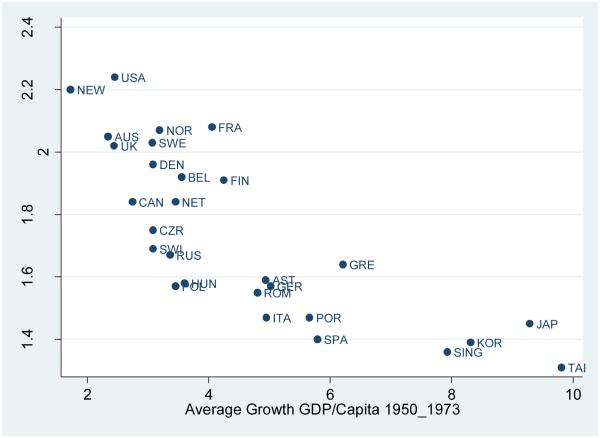

A similar pattern prevails when using GDP growth rates as the proxy for development pace: regressing present-day fertility measures (i.e., 1979 cohort fertility) on Maddison’s computed GDP growth rates from 1950-1973 illustrates that among today ’s developed countries, those that experienced fast economic growth during the mid-century currently have the lowest fertility rates, while relatively high fertility prevails in countries that experienced only moderate growth during this time.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Adopting a long-term perspective of low fertility across the 20th century, this paper provides novel theoretical insights into the interrelations between low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. We have argued that the pace and onset of socioeconomic development are inherently linked with different gender equity regimes—a key driver of fertility variation within developed countries. Moreover, the pace of socioeconomic development emerges in our framework as a predictor of how low fertility drops towards the end of the fertility transition. We also shed light on a demographic feedback mechanism we call the gender-equity dividend. During this dividend, a young adult age structure (caused by below-replacement fertility) yields a relative scarcity of women relative to men (given the prevailing gender-differences in the age at marriage). In turn, these age structures facilitate changes in gender-norms in the egalitarian direction through increased female bargaining power. Greater gender equity is then likely to help raise or stabilize fertility in low-fertility high-income countries. In this process, therefore, the emergence of below-replacement fertility implies a homeostatic mechanism that over the medium/long-term can contribute to increases in fertility, such as has been documented in some advanced countries with high levels of gender equity in recent decades. This theory helps explain the fertility pattern in countries such as S. Korea, where a rapid decline in fertility during the demographic transition has resulted in very low contemporary fertility levels associated with relatively high levels of household gender inequity. Piecing together these insights, we propose a variant of the demographic transition that accounts for the interplay between changes in fertility and changes in gender equity.

Should our theory hold up, fertility will nudge closer to desired fertility levels in the today’s “developed world” as the gap between incoherent “institutional” and “family” oriented gender equity continues to close. This will not only continue to occur in first-wave developers but also begin to accelerate in second-wave developers.

Furthermore, if one assumes the development of incongruent realms of gender equity is inevitable and generalizable, today’s swiftly developing countries (including China, India, and Brazil, where nearly 3 of the world’s 7 billion citizens live) could well enter periods of very low fertility. Indeed, such a scenario is already playing out in in Brazil, where fertility has been below the replacement level for nearly a decade, and urban China, where cities like Shanghai have documented TFRs under one (Lutz 2009; see also, Lutz 2008). Our theoretical framework gives reason to cautiously speculate that “third-wave” developers” – including countries such as China, Brazil, and India – could replace second-wave developers as the new frontier of low and lowest-low fertility in the 21st century.

Necessarily a broad theory of development and fertility such as the one presented here oversimplifies a number of complex, nuanced aspects of the interrelations between low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. As a result, this paper suffers from a number of limitations.

The first limitation is that our theory does not take into account other factors contributing to low fertility. We highlight some processes, including changing gender norms during the development process, that in our opinion had a profound impact on fertility across many contexts and at different time periods, and which are essential for understanding future fertility patterns in high-income countries that have had experienced persistent low fertility for a substantial period, and middle-income countries into which below-replacement fertility is spreading. But it is also clear that incongruent levels of gender equity (i.e., a strong work-family conflict) were not the sole driver of low fertility in early 20th century, nor are they the sole driver of low fertility today (see Van Bavel (2010) and Caldwell and Schindlmayr (2002)). Out of various economic, cultural, and social contexts emerge forces that either foster or hinder the realization of desired fertility. For example, economic conditions in Eastern Europe have been linked to low fertility since the fall of the Iron Curtain (e.g., Witte and Wagner 1995; Filipov and Dorbritz 2003; Caldwell and Schindlmayr 2002; Thornton and Philipov 2009). In East Asia, the high pressure on parents to provide costly private education has elevated the price of children so much that many families face a strong quality-quantity trade-off (Anderson and Kohler 2013).20 And long-standing, high levels of youth unemployment may encourage childbearing postponement in Southern Europe, which has been documented as a driver of very low period TFRs and may impact completed childbearing levels (Kohler et al. 2002; Lutz et al. 2006).

The second limitation of this paper is that it fails to adequately explain how the mid-century baby boom squares in with the story we tell, and why women in the 1940s-1960s withdrew into housewifery.21 The baby boom was not only a period of high fertility and nuptiality, but also of traditional breadwinner roles in the household and a widespread acceptance of these roles (Coontz 2011).22 Several explanations exist as to why these transitorily reemerged as the hegemonic norms. One explanation, put forth by Doepke et al. (2007), argues that younger women in mid-20th century were crowded out of the labor market by men who had returned from WWII and by older women who had gained experience in the labor market during the war. As a result of these worsening labor market prospects of young women, many decided to marry and have children. Another explanation for the return to traditional breadwinner roles during the baby boom is that high scale female labor force participation during WWII created a post-war environment in which working mothers became even more heavily stigmatized. Terms such a “latchkey children” and “eight-hour orphans” were used during to war to refer to children whose “neglectful mothers” left them during work (Zucker 1944). Just after the war, hostile attitudes toward working mothers disseminated throughout the country, and “a concerted effort developed to defend traditional values” (Chafe 1976, p. 16).23 According to Chafe (1976, p. 20), “[m]agazines during the 1950s celebrated the virtues of “togetherness” and advertisers attempted to sell their product by showing families with four children—the ‘average’ American family—out on a picnic or vacation. Public opinion polls showed that the vast majority of Americans did not question the traditional allocation of sex roles and believed that a woman’s primary place was in the home. Thus, while traditional breadwinner roles reigned during the baby boom era, spanning from the mid-1940s to early 1960s, female labor force participation aspirations remained lower than early 20th century levels in most countries (Appendix II).24 Ruggles (2015) argues that the period of the baby boom is unusual in the sense that an exceptionally strong male wage growth in the post-WWII years has prolonged the patriarchal family model that persisted earlier in the 20th century. Only this rapid wage male growth made a male-breadwinner model economically sustainable for a large fraction of the population, and along with it, the persistence of relatively traditional gender norms, a weak work-family conflict, and as a result, relatively high fertility. But this period was unusual. Nevertheless, it is consistent with our framework in that a lack of gender-equity and a weak work-family conflict (see bottom-right quadrant in Figure 2), driven in part by economic factors and unique post-WWII social and demographic factors, importantly contributed to the high fertility during the baby boom. Hence, while our theory focuses on recent fertility trends in mostly high-income countries, the basic mechanisms of our framework are likely to have shaped the baby boom as well.25

Countries that represent outliers to our theoretical framework present a potential third limitation of our theoretical model. In particular, Germany and Austria stand out for being countries that began industrializing in the early 20th century along with other first-wave developers. Yet unlike other first-wave developers, Germany and Austria still exhibit very low fertility. The German-speaking fertility pattern is unique compared to other low fertility settings in Europe due to its high rates of childlessness but relatively high progressions to second and third birth rates (Sobotka 2008). Recent research suggests that institutional factors, such as family and labor market policies, likely explain the “Western European fertility divide” between Germany and other Western countries (Klüsener et al. 2013), and that Germany and Austria—along with the other Axis powers, Italy and Japan—experienced cultural and institutional responses to the war that have negatively impacted their fertility levels (Weinreb and Johnson-Hanks 2014). Germany and Austria, like other first-wave developers, exhibited population age structures conducive to gender equity change in the mid-20th century; however, unlike places such as Sweden and the US, the institutional, cultural, and economic factors promoting greater gender equity were not present in Germany and Austria during their “gender-equity dividend”. These two countries face a comparatively weak policy environment for career-oriented women wishing to have a family, as exemplified by a tax code that penalizes working mothers, and by a lack of inexpensive daycare facilities for dual-earner households. Moreover, it is common in Germany and Austria that working mothers participate in the labor market only part-time (that is, women have “one foot in the labor market and another in the traditional domestic sphere”), which, in effect, may not be sufficient to catalyze men’s adoption of more gender symmetric behavior. Hence, while the mechanisms underlying the gender-equity dividend are likely to have been at work in both Germany and Austria, the specific institutional context of these countries has limited the extent to which it resulted in increased gender equity, increased female labor force participation and higher fertility. While some of the specific institutional factors driving the somewhat distinct German and Austrian fertility regime have frequently been emphasized in the literature, the literature may still benefit from research that investigates why Germany and Austria have been slow to adopt the more family-friendly environments that have arisen in other Northern/Western European countries and other 1st-wave developers during the 2nd half of the 20th century.

Lastly, our theory does not account for important within-region and within-country heterogeneity with regards to fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender norms. Fertility rates as well as socioeconomic indicators between Southern Italy and Northern Italy, for example, differ starkly from one another (Caltabiano et al. 2009). Further research considering these important areas of heterogeneity may shed light on diffusional factors relating to gender equity change.

Figure 9. Cohort Fertility (1979) on Annual Average GDP/Capita Growth (1950-1973).

Source: Myrskylä et al. (2012) and Maddison (2007)

Acknowledgements

This research received support from the Population Research Training Grant (NIH T32 HD007242) awarded to the Population Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania by the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH)’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors are grateful for helpful comments from Kristen Harknett, Frank Furstenberg, Ronald Rindfuss, Tomáš Sobotka, and Jan Van Bavel.

Appendix I

We use economic and development indicators (e.g., GDP and HDI) to dichotomize today’s “developed world” into first-wave and second-wave developers.

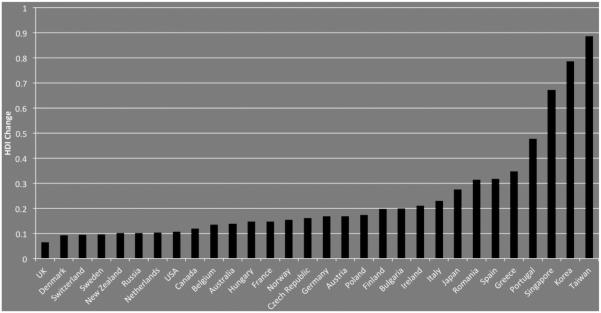

First we examine the percent change in HDI between 1950 and 2012. HDI values for 2012 come from the United Nations (2012), and mid-century HDI figures from Crafts (2002). One notes that countries that experienced large percent increases between 1950-2012 in HDI, appearing to the right of the Figure, are clustered in East Asia (Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan), Southern Europe (Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Italy), and Eastern Europe (Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland). Conversely, countries that were relatively highly developed in the mid-century—first-wave developers—are clustered on the left of Figure 11.

Some countries appear to have not changed much in “development” between 1950 and 2012. The UK is a prime example: life expectancy and GDP per capita in the UK increased substantially during this time period (69.2→80 years and $6,847→ $32,738, respectively), though the change in HDI lies around a mere 6.5%.

The reason why the UK does not appear to have not progressed much is that yearly HDI calculations are made using different maximum values for the “health and wealth” components (life expectancy and GDP per capita). Because our HDI figures for 1950 are uniformly calculated using the same maximum value for all countries, the percent change in HDI provides a useful tool to assess the speed with which our selected countries developed.26 For more information, see Crafts (2000).

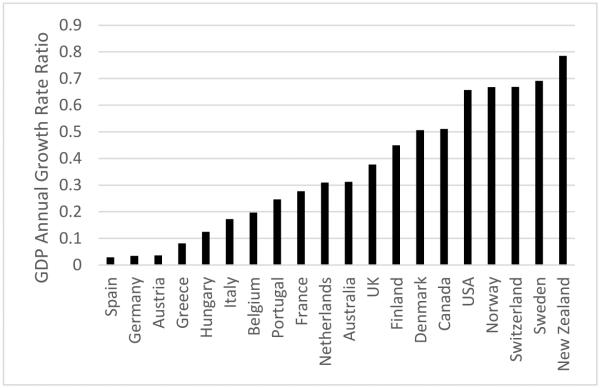

Figure 10.

% HDI Change Between 1950 and 2012

We also examined the pace of economic growth in the early 20th century relative to the mid-20th century. The idea is that countries that experienced rapid economic development in the early half of the century would fall into the “first-wave developer” category and those that experienced very fast growth in the mid to latter half of the 20th century would be considered “second-wave developers”. We use average GDP per capita growth rates computed by Maddison (2007) for the periods 1913-1950 and 1950-1973. Dividing the second average by the first illustrates the ratio of growth between the two periods. Thus, .5 for example would indicate that GDP growth during the period 1913-1950 was half as much as between 1950-1973. These values are illustrated in tabular as well as graphical form in Table 3 and Figure 12.

Table 3.

GDP Annual Growth Rate Averages (1913-1950)/(1950-1973)

| GDP Annual Growth Rate Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 1913-1950 | 1950-1973 | Ratio |

| Spain | 0.17 | 5.79 | 0.029 |

| Germany | 0.17 | 5.02 | 0.034 |

| Austria | 0.18 | 4.94 | 0.036 |

| Greece | 0.5 | 6.21 | 0.081 |

| Hungary | 0.45 | 3.6 | 0.125 |

| Italy | 0.85 | 4.95 | 0.172 |

| Belgium | 0.7 | 3.55 | 0.197 |

| Portugal | 1.39 | 5.66 | 0.246 |

| France | 1.12 | 4.05 | 0.277 |

| Netherlands | 1.07 | 3.45 | 0.31 |

| Australia | 0.73 | 2.34 | 0.312 |

| UK | 0.92 | 2.44 | 0.377 |

| Finland | 1.91 | 4.25 | 0.449 |

| Denmark | 1.56 | 3.08 | 0.506 |

| Canada | 1.4 | 2.74 | 0.511 |

| USA | 1.61 | 2.45 | 0.657 |

| Norway | 2.13 | 3.19 | 0.668 |

| Switzerland | 2.06 | 3.08 | 0.669 |

| Sweden | 2.12 | 3.07 | 0.691 |

| New Zealand | 1.35 | 1.72 | 0.785 |

Figure 11.

GDP Annual Growth Rate Averages (1913-1950)/(1950-1973)

Some countries fit nicely within our dichotomous framework. Clear first-wave developers would be the United Kingdom (UK), France, Sweden, Denmark, Luxembourg, the United States of America (USA), Iceland, Canada, Switzerland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Belgium, Finland, Norway, Australia, and Austria. Second-wave developers would include Spain, Italy, Portugal, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Poland, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

Some countries lie somewhere between first and second-wave developers. Above all, Germany, Italy, and Japan share characteristics with both first-wave and second-wave developers. On the one hand, these three countries had experienced economic growth and improvements in living standards prior to WWII, and were integral players in the early 20th century global economy. On the other hand, the war-torn and politically fragmented Axis powers all experienced drastic setbacks in living standards during the war (see Scheck 2008; Zamagni 1993; and Dower 2000). These years of hardship were followed by “economic miracles” (“il miracolo economico” in Italian, “Der Wirtschaftswunder” in German, and “ ” in Japanese), which set the course for these “post-war re-developers” to quickly improve living standards and regain their foothold as economic powerhouses. Thus, while post-war re-developers historically align with first-wave developers, they have experienced quick development over the second half of the 20th century, and as such, share many of the same demographic and social characteristics with other second-wave developers.

” in Japanese), which set the course for these “post-war re-developers” to quickly improve living standards and regain their foothold as economic powerhouses. Thus, while post-war re-developers historically align with first-wave developers, they have experienced quick development over the second half of the 20th century, and as such, share many of the same demographic and social characteristics with other second-wave developers.

Appendix II

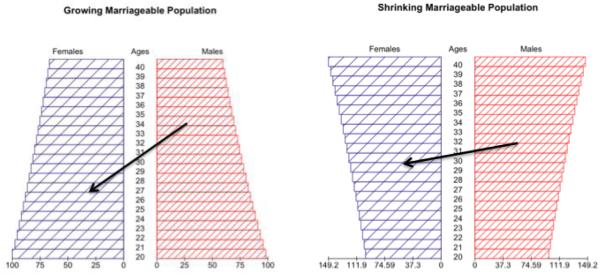

Figure 12. Female Labor Force Participation Rates for Select First-Wave Developers, 1900 and 1960.

Source: Olivetti (2013)

Footnotes

The authors are grateful for helpful comments from Ronald Rindfuss, Tomas Sobotka, Jan Van Bavel, and three peer-reviewers.

These include the other English-speaking non-European countries Australia, New Zealand, the US, and Canada.

For the United States, these rates undercount people working as boardinghouse keepers, unpaid family farm workers and manufacturing workers in homes and in factories (Olivetti 2013). Additionally, Olivetti calls for caution when analyzing historical FLFPR, as country-wide differences in the definition of “economically active” exist. The rates presented largely reflect the proportion of the female population (both married and unmarried) that “receives a wage”.

McDonald (2013) distinguishes between “gender equity” and “gender equality” by stating that “gender equity is about perceptions of fairness and opportunity rather than strict equality of outcome”, and argues that the former is more important than the latter concerning fertility decision-making.

Among contemporary demographers, low fertility during the early half of the 20th century in Western Europe is frequently attributed as a consequence of economic and political instability during the interbellum period (e.g., Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 1988; Sobotka 2008; Frejka and Sardon 2004). In recent years, however, this claim has been empirically refuted. Van Bavel (2010), for example, argues that low fertility during the interwar period was due to processes now associated with the Second Demographic Transition rather than economic hardships. In initial disbelief to Van Bavels findings, Goldstein (2012) modestly exclaimed that after “torturing the data”, he was not able to find any effect of the great depression on fertility rates, and conceded to Van Bavel’s argument.

In fact, the “competition” between FLFP and fertility has dominated much of the contemporary fertility literature as well, and has been well-supported in empirical examples (e.g., Butz and Ward 1979; Engelhardt et al. 2004; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Kohler et al. 2006). Thus, while early scholars “speculated” about the causal relationship between FLFP and fertility, subsequent research well up into the 21st century has corroborated it with more sophisticated methodological techniques.

Analyzing data from the Netherlands and United States, Hagestad and Call (2007) note that high levels of childlessness in the early 20th century served as “indications that some of these women may have been forerunners of what we consider a “modern” pattern: actively choosing childlessness and stable work engagement”.

We compare cohort net reproduction rates rather than period NRRs because the former better reflects the actual number of children born to a birth cohort of women while the latter is a synthetic measure subject to distortive tempo effects (Bongaarts and Feeney 1998).

Because cohorts born in 1979 have not yet finished their childbearing years, we use Myrskylä et al.’s (2013) recently published cohort fertility projections.

A recent literature has started to revisit the relationship between schooling and fertility in highly developed societies, and some studies have claimed that the fertility of highly-educated women has been rising. While this is correct, there is currently no evidence that the schooling gradient in fertility has changed in fundamental ways for women. For instance, in Norway (the world’s second most “prosperous” country, after Luxembourg, in terms of GDP per capita), Kravdal and Rindfuss (2008) show that more recent birth cohorts of higher educated women (born 1960-1964) have much higher fertility and lower levels of childlessness than their older counterparts (born 1940-1955); however, higher educated women still have fewer kids than less educated Norwegian women. For other Scandinavian countries, Andersson et al. (2009) find that although fertility differentials by education in Northern Europe have begun to dissipate, highly educated women still have fewer children than their less educated counterparts.

As part of changing gender equity, assortative mating patterns have changed, as evidenced by the widely documented pattern of increased educational homogamy.

While we report absolute differences in unpaid work, the relative differences between first and second-wave developers are equally stark. For example, in Denmark the ratio of men/women unpaid work differences stands around 72% while in Korea the ratio hovers around 20% (Miranda 2011).

Cohorts not having finished their childbearing years (e.g., 1965-1979) have been projected by Myrskylä et al. (2013)

Feyrer et al. (2008, p. 21) express similar optimism for European countries where household norms remain traditional: “In the lowest fertility European countries the progress of women is limited both in the workforce and in the household relative to other high income countries. We see this as a temporary state. The social structure in these countries and the division of child care has led women to choose to have fewer children than did their mothers, but we see no reason why these social factors cannot also work in the other direction and lead to future increases in fertility.”

Van de Kaa (1987, p. 11) states that Denmark and Sweden are the “[o]nly two European countries [that] appear to have experienced the full sequence of changes in family formation that have led to very low fertility”.

While period total fertility rates for some first-wave developers fluctuated quite markedly during the latter half of the 20th century, cohort total fertility rates remained relatively stable (see Myrskylä et al. 2013). Sweden is a prime example: its period total fertility rate fluctuated from 2.13 in 1990 to 1.5 in 1999, though cohort fertility in Sweden has hovered around 2 births per woman for women born 1930-1965.

Other contributing factors to East Asia’s ultra-low fertility rates, such as a stronger “quality-quantity” tradeoff have also been tied to the region’s fast pace development story (Anderson and Kohler 2013).

Goldin makes this observation for educated women in the United States, but we argue that it is applicable to other first-wave developers.

As is apparent in Figures 7 and 8, while the pace and onset of development are strong predictors of how low fertility will drop, they do not fully explain heterogeneity in specific lowest levels of fertility.

It has been argued that the surge in competition among youth, which has led to the a strong quality-quantity trade-off in the region, can be partly attributed to East Asia’s rapid socioeconomic development (Anderson and Kohler 2013).

It is important to stress that there was significant heterogeneity in baby booms across high-income countries in the mid 20th century, both in terms of the “quantum” and “tempo” of fertility (Van Bavel and Reher 2013)

Coontz (2011, p. 39) asserts that “even women who had experienced other models of family life and female behavior said that during the 1950s they came to believe that normal families were those where the wife and mother stayed at home, and that normal women were perfectly happy with that arrangement.”

In 1944, the Chairman of the Womanpower Committee of the War Manpower Commission in the Cleveland area predicted that “[w]e can expect the voices of the supporters of the back to the home movement to be louder and stronger than in the days of the depression. One of the reasons for this is because “[t]he consciousness of the value of children quickened through war and the belief that the child is best taken care of in the home by his mother” (Michel 1999, p. 49).

In the United States, FLFP actually increased between 1900 to 1960, though this was likely due to a greater share of older women working (Doepke 2007)

It is beyond the scope of this paper to do so, but we believe that our understanding of fertility dynamics would greatly benefit from empirical analyses on the origins and consequences of the baby boom that adopt the theoretical framework outlined in this paper.

The United Nations recognizes that because their HDI calculations are relative, it poses difficulties for researchers in comparing HDI figures over time for individual countries. The UN therefore released “Hybrid HDIs” for the years 1970-2010 which attempt to solve this problem. However, we do not use these figures because they are not available before 1970 and therefore do not capture the advances in development made in the 1950s and 1960s in many developed countries.

Works Cited

- Anderson Thomas M., Kohler Hans-Peter. Education fever and the East Asian fertility puzzle: A case study of low fertility in South Korea. Asian Population Studies. 2013;9(2):196–215. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2013.797293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Gunnar, Rønsen Marit, Knudsen Lisbeth B., Lappegård Trude, Neyer Gerda, Skrede Kari, Teschner Kathrin, Vikat Andres. Cohort Fertility Patterns in the Nordic Countries, Demographic Research. 2009;20(14):313–352. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist Joshua. How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America's second generation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2002;117(3):997–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Bellavia Gina M., Frone Michael R., Kelloway E. Kevin, Frone Michael R. Work-family conflict. In: Barling Julian., editor. Handbook of work stress. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2005. pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne M., Milkie Melissa A., Sayer Liana C., Robinson John P. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne M., Robinson John P., Milke Melissa A. Changing rhythms of American family life. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom David, Canning David, Sevilla Jaypee. The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change. Rand Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Feeney Griffith. On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review. 1998;24(2):271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Watkins Susan Cotts. Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review . 1996;4(22):639–682. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster Karin L., Rindfuss Ronald R. Fertility and women's employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:271–296. [Google Scholar]

- Butz William P., Ward Michael P. The emergence of countercyclical US fertility. The American Economic Review. 1979;69(3):18–328. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C., Schindlmayr Thomas. Explanations of the fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities. Population Studies. 2003;57(3):241–263. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000137790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caltabiano Marcantonio, Castiglioni Maria, Rosina Alessandro. Lowest-low fertility: Signs of a recovery in Italy. Demographic Research. 2009;21:23–681. [Google Scholar]