Abstract

Schizophrenia has been classically described to have positive, negative, and cognitive symptom dimension. Emerging evidence strongly supports a fourth dimension of social cognitive symptoms with facial emotion recognition deficits (FERD) representing a new face in our understanding of this complex disorder. FERD have been described to be one among the important deficits in schizophrenia and could be trait markers for the disorder. FERD are associated with socio-occupational dysfunction and hence are of important clinical relevance. This review discusses FERD in schizophrenia, challenges in its assessment in our cultural context, its implications in understanding neurobiological mechanisms and clinical applications.

Keywords: Assessment, facial emotion recognition, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Homo sapiens are considered as social animals with a highly evolved “social brain” as an adaptive response to an increasingly complex social environment.[1] Charles Darwin in his historical book has suggested that emotions in man have evolved through a process of natural selection, and facial expression is an important means to communicate emotions and intentions. This ability of processing emotional information is probably what gives man his survival advantage in the race of evolution. The ability to understand the mental state of others, and recognize facial emotional expressions forms an important part of social cognition which also involves - face perception, emotional processing, theory of mind, self- reference and working memory.[2] Emotional dysregulation is a common feature of most psychiatric disorders ranging from psychosis, mood disorders, and anxiety spectrum disorders. Recently, facial emotion recognition deficits (FERD) have been consistently demonstrated in schizophrenia, suggesting that aberrant processing of emotional information could be intrinsically linked to the evolution of psychopathology. This review discusses FERD in schizophrenia, challenges in its assessment in our cultural context and its implications in understanding neurobiological mechanisms and clinical applications.

ASSESSMENT OF FACIAL EMOTION RECOGNITION DEFICITS

Pioneering work in the field of emotion recognition was done by Izard and Ekman and Friesen. They gave a description of the six basic human emotions of happy, sad, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust and also first devised a tool with a set of black and white photographs of posed emotions restricted in ethnicity and age. Many other tools to assess facial emotion recognition abilities have been described such as the PENN emotion recognition test.[3]

Limitations of available tools

However, Western tools have limited applicability in Indian setting. Perception of emotion is known to be influenced by ethnicity.[4] In a meta-analysis of the cultural specificity of emotion recognition, an in group advantage was found where emotions were recognized more accurately when they were both expressed and perceived by members of the same national or ethnic group.[5] Further stimuli capturing more closely the dynamic, full color, full-channel nature of emotional expressions would bolster the ecological validity of future studies.[6] Hence to overcome these limitations of existing tools, we developed a novel ecologically valid and culturally sensitive tool for use in the Indian population which could be used to assess FERD in various neuropsychiatric disorders.

TOOL FOR RECOGNITION OF EMOTIONS IN NEUROPSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

The tool[7] consists of two arms – the static (still photographs) and the dynamic (videos) arm. Four trained actors (one young male, one young female, one older male, and one older female) who had an experience of around 10 years acting in theater were chosen. They were asked to emote the six basic emotions of happy, sad, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust at two different intensities high and low along with neutral facial expressions. Still photographs using a five mega pixel digital camera and videos using an analog video camera were taken. A three-point lighting system was used to avoid any background shadows and enhance picture quality. All pictures were taken from a fixed distance of three feet. Dynamic images were converted from the AVI to MPEG format and edited using a professional video editing software, in order to obtain four second video clips of each emotional expression. All dynamic images had emotions expressed in a single intensity but for the static images emotions were expressed at two different intensities. The images were then arranged in a random order using random number generator software and separate power point presentations were prepared for the static and dynamic images with the images appearing in the random order sequence. A total of 52 static and 28 dynamic images were obtained.

Validation of the tool

The tool was validated by 51 students the Departments of Psychiatry, Clinical Psychology and Psychiatric Social Work at National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru. The images were viewed on a 15-inch computer monitor from a distance of 1 m in a closed room without any external distractions. Images (not used in the final tool) of the various emotions were shown as examples to ensure that the subjects understood the meaning of the emotions expressed. The subjects first viewed the static and then the dynamic images and had to select one correct response from the seven alternatives (neutral, happy, sad, fear, anger, surprise, disgust) given to them for each image viewed (forced choice response method). There was no time limit given for viewing and marking the responses. The tool was also validated by five qualified psychiatrists in the manner as described above. The tool was found to have good inter rater agreement of 60% for static and 80% for dynamic images with Cronbach alpha score of internal consistency at 0.7.[7]

FACIAL EMOTION RECOGNITION DEFICITS IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

Facial emotion recognition deficits have been consistently demonstrated in schizophrenia and are found to be specific for negative emotions of fear, anger, and disgust.[8,9,10] Some of the previous studies on chronic schizophrenia patients did not find any correlation between FERD and psychopathology, indicating that they could be trait related deficits.[11,12] However, some other studies found a correlation between FERD and negative symptoms of alogia[10] apathy and affective flattening[13] and also positive symptoms of hallucinations and delusions.[10,13,14] In a meta-analytic review Kohler et al.[15] demonstrated robust effect sizes for deficits in both facial emotion identification as well as differentiation in patients with schizophrenia.

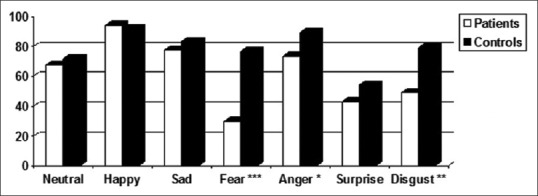

We used the tool to assess FERD in a sample of 25 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients in comparison to 30 healthy controls.[16] In this study, we found significant impairment in total accuracy scores in schizophrenia patients as compared to healthy controls (P < 0.001). Further on analysis of individual emotions the difference was significant for negative emotions of fear (P < 0.001), anger (P = 0.01) and disgust (P = 0.001) [Figure 1]. On correlation analysis, there was a significant negative correlation between negative symptoms and accuracy scores. These findings were consistent with earlier studies and provided internal validity for the tool in assessing FERD in schizophrenia patients in Indian context. This study also established for the first time that FERD are present even in the antipsychotic naïve state and are one among the important deficits in schizophrenia. These findings were replicated in an independent sample of schizophrenia patients in remission as a part of on-going study comparing FERD between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients. Hence, FERD seem to be stable deficits persisting in both acute as well as remission phase of schizophrenia.

Figure 1.

Comparison of tool for recognition of emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders accuracy percentage scores in patient versus control group

ERROR PATTERNS AND ENHANCED EMOTIONAL THREAT PERCEPTION IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

In addition to magnitude of errors, schizophrenia patients have also been demonstrated to have differential patterns of misidentification of emotional stimuli. Patients tend to misidentify neutral emotions as threat emotions such as anger.[3] Paranoia is an essential feature of psychopathology in schizophrenia. Green and Phillips in their review have described heightened threat perception as a possible mechanism for the development of persecutory delusions.[17] This is based on evidence of differential emotion recognition in paranoid patients and attentional biases toward threat-related stimuli as demonstrated on attention tasks and visual scan path analysis. The authors describe a social threat perception model where schizophrenia is conceptualized as a disorder of enhanced threat perception.

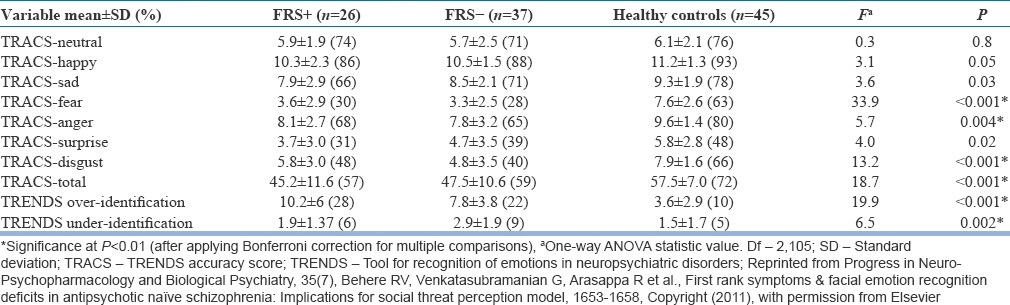

We tested this hypothesis on a sample of 63 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients in comparison to 45 healthy control subjects.[18] The emotions of fear, anger, and disgust were labeled as “threatful” emotions. And the emotions of neutral, sad, happy were labeled as “nonthreatful” emotions. The classification of emotions of anger, fear, and disgust as threatful emotion was based on the premise that these emotions would denote “threat” to oneself or in the environment. The patient groups were subdivided into those who experienced Schneiderian first rank symptoms of schizophrenia (and hence would experience paranoia) and those who did not. The study found that patients with first rank symptoms significantly overidentified nonthreatful emotions as threatful as compared to patients without first rank symptoms and healthy controls (F = 19.9, P < 0.001) [Table 1]. The results of this study supported the social threat perception model of schizophrenia and suggested that enhanced emotional threat perception is intrinsic to the evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia.

Table 1.

Comparison of emotion recognition scores between FRS+, FRS− group, and healthy controls

IMPLICATIONS FOR NEUROBIOLOGY OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Phillips et al.[19] have suggested that emotional processing may be dependent upon the functioning of two neural systems: A ventral system including the amygdala, insula, ventral striatum, and ventral regions of the anterior cingulate gyrus, and prefrontal cortex, which is important for identification of the emotional significance of environmental stimuli and the production of affective states. The dorsal system includes the hippocampus, dorsal regions of the anterior cingulate gyrus and the prefrontal cortex which is important for the performance of executive functions and effortful rather than automatic regulation of affective states.

These are supported by findings of functional imaging studies during emotion perception tasks which have demonstrated enhanced activation of limbic areas and reduced activation of prefrontal cortical areas and insula. The prefrontal cortical areas; primarily involved in the regulation of emotion perception includes the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex. A meta-analysis of functional imaging studies by Li et al. (2010)[20] revealed an under-recruitment of the amygdala and limitation in activation of the ventral-temporal-basal ganglia-prefrontal cortical circuit in schizophrenia patients while processing facial emotions.

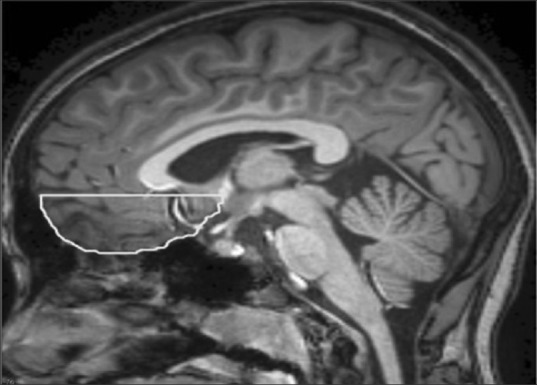

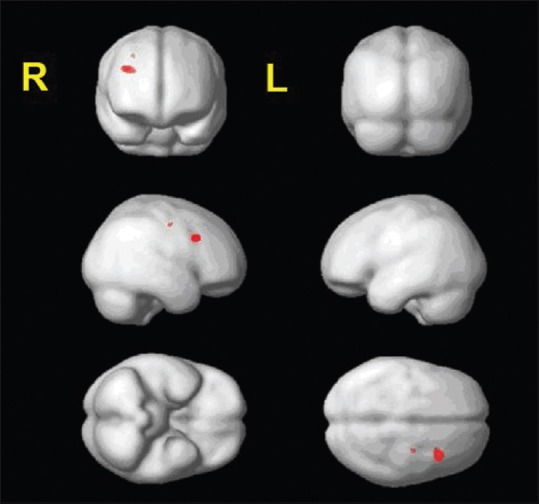

We attempted to examine orbitofrontal cortex volume deficits using manual morphometric techniques using 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on sample of 14 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients.[21] Schizophrenia patients were found to have significantly smaller Orbitofrontal cortex volumes as compared to healthy controls (P = 0.03) [Figure 2]. The findings of this study provide evidence for orbitofrontal dysfunction in schizophrenia which may lead to abnormal emotional processing through fronto-limbic circuits and may have implications for understanding evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia. In another neuroimaging study, we studied for the first time, gray matter volume correlates of enhanced emotional threat perception using voxel-based morphometry (VBM).[22] 24 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients were assessed on tool for recognition of emotions in neuropsychiatric disorders (TRENDS) and 3 Tesla MRI were obtained. The number of “nonthreatful” emotions that were misidentified as any of the “threatful” emotions were assessed and termed as TRENDS over-identification score. On VBM analysis, a significant correlation was found between TRENDS over-identification score and gray matter volume loss in the right prefrontal cortex [Figure 3]. The right hemisphere has been predominantly implicated in emotional processing of threat-related emotions such as fear and anger. Right hemisphere-related cognitive processes have been described to be dysfunctional in schizophrenia. The findings of this study support the “right brain” hypothesis of schizophrenia and suggest that a specific right prefrontal cortex deficit may be associated with enhanced emotion threat perception in schizophrenia.

Figure 2.

Manual morphometric tracing of orbitofrontal cortex

Figure 3.

Voxel-based morphometry analysis showing right prefrontal cortex gray matter volume deficits associated with enhanced emotional threat perception

Model for understanding evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia

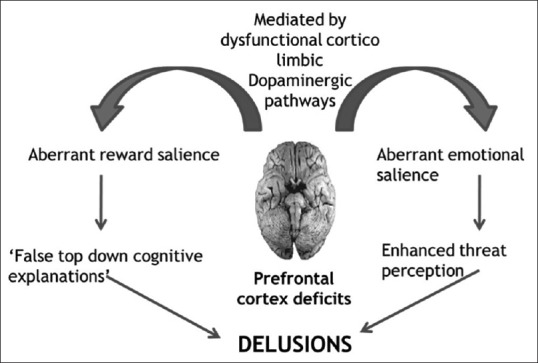

Based on synthesis of our understanding of the neurobiological basis of emotional processing and findings of prefrontal cortex deficits underlying emotional threat perception, we propose a model to understand the evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia [Figure 4]. Dopaminergic-mediated prefrontal limbic pathways are critical to the processing of salience associated with emotional stimuli.[23] Aberrant prefrontal limbic circuits coupled with aberrant limbic activation lead to an undue importance or salience being associated with nonthreatful emotional stimuli (facial expressions). The prefrontal cortex; which is associated with regulation of processing of emotional information, is deficient. This results in generation of false top-down cognitive explanations in response to the aberrant salience attached to emotional stimuli, ultimately leading to the crystallization of delusions.

Figure 4.

Model for understanding evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia

FACIAL EMOTION RECOGNITION DEFICITS: A NEURODEVELOPMENTAL MARKER FOR SCHIZOPHRENIA?

Facial emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia have been consistently demonstrated to be one among the important deficits in schizophrenia and may play a role in the evolution of psychopathology. However, this brings us to a pertinent question whether these deficits are state-related or are they trait markers of the disorder and persistent throughout the course of the illness. Studies examining facial emotion perception in first degree relatives of schizophrenia have demonstrated FERD in pro-bands of schizophrenia in comparison to healthy controls. Longitudinal studies have further demonstrated that FERD tend to remain stable over a 12-month follow-up period.[24] Suggesting that these deficits may be a trait marker for schizophrenia.

To address this issue, we attempted to study the association of FERD with neurological soft signs (NSS) in schizophrenia. NSS are robust neurodevelopmental markers in schizophrenia. We examined NSS and TRENDS in 29 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients.[25] Greater primitive reflex score correlated with greater errors of over-identification. Greater motor-coordination sub score also correlated with lower accuracy score on TRENDS. The results of this study for the first time demonstrated an association between enhanced emotional threat perception and a robust neurodevelopmental marker such as NSS. This supports emotional threat perception as an endophenotypic marker for schizophrenia. The endophenotypic validity of FERD is further supported by recent Genome-wide association studies.[26] This finding can have important implications in utilizing emotion perception as neurobehavioral probes in functional imaging paradigms.

FACIAL EMOTION RECOGNITION DEFICITS AND RELATIONSHIP TO SOCIAL FUNCTIONING IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

A number of studies have looked at the relationship between FERD and social functioning. Kee et al. studied this relation by applying the Strauss-Carpenter outcome scale and the role functioning scale which looks at work productivity, independent living, and relationships with family and friends with a follow-up assessment after 12 months.[27] They found a significant correlation between FERD and work functioning and independent living at baseline and 12 months later. Even with adequate job skills and work habits patients’ difficulty in understanding emotion in others could lead to inappropriate responding which might hamper their ability to carry out job requirements. Horan et al. in a 12-month longitudinal study found deficits in social cognition domains of emotion processing and theory of mind to be stable deficits over the course of illness.[24] Better performance on emotion recognition tasks was found to be associated with greater work performance and social functioning. Hence, FERD have a direct impact on socio-occupational functioning and are of important clinical relevance.

In a longitudinal study on predictors of long-term functional outcome in schizophrenia, we attempted to analyze the association between socio-occupational functioning and FERD.[28] 14 schizophrenia patients who were assessed on NSS and MRI was done at baseline; were reevaluated after mean follow-up period of 74.2 ± 24.2 months. On follow-up, functioning was assessed using socio-occupational functioning scale and FERD using TRENDS. Dorsolateral prefrontal lobe volume of baseline MRI scans was analyzed using manual morphometric techniques. Poorer socio-occupational functioning was found to be associated with greater errors on TRENDS accuracy score and lower dorsolateral prefrontal lobe volume at baseline predicted poorer socio-occupational functioning. The results of this study support the importance of FERD in mediating socio-occupational functioning in antipsychotic stabilized schizophrenia. Hence, FERD have a direct impact on socio-occupational functioning and measures toward ameliorating these deficits are of important clinical relevance.

Clinical implications

Synthesis of the evidence above suggests that FERD is one among the important deficits in schizophrenia. These deficits could be present in antipsychotic naïve stated, can persist throughout the illness and may be endophenotypic markers of schizophrenia. FERD are also associated with impaired socio-occupational functioning and hence treatments focused on these deficits are of important clinical relevance.

Pharmacological treatment

Few studies have examined the effect of antipsychotic treatment on FERD in schizophrenia patients.[29,30,31] Harvey et al. in an 8-week study found beneficial effects of risperidone and quetiapine in improving measures of social task performance.[29] Similar beneficial effects on FERD have also been reported with modafinil and intranasal oxytocin administration.[23] Most of the earlier studies have examined effects of medications in patient groups who were already on treatment of schizophrenia. Hence, while antipsychotics have been demonstrated to have beneficial effects on positive, negative as well as certain cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, the nature of FERD in the antipsychotic-naïve state and the impact of subsequent neuroleptic treatment on emotion recognition deficits are yet to be established with certainty.

We assessed emotion recognition abilities in sample of 25 antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia and reassessed the performance on TRENDS after 1-month of antipsychotic treatment with risperidone at a dose of 4 mg/day.[16] On follow-up, a significant improvement in TRENDS accuracy score (P = 0.02) and accuracy score for the emotion of disgust (P = 0.002) was found. The results of this study demonstrated improvement in FERD after initiation of antipsychotic from a drug naïve state. This study also supports the model of evolution of psychopathology proposed earlier wherein dopamine-mediated frontolimbic dysfunction was considered to be associated with enhanced emotional salience.

Nonpharmacological interventions

It has been firmly established that emotion recognition defects are associated with decreased social functioning irrespective of symptomatology. Hence, there is a potential for nonpharmacological methods as an adjuvant in the multimodal treatment approach of schizophrenia, targeting the collective improvement of positive, cognitive, and affective symptom domains.[32] An established technique of “cognitive enhancement therapy” (CET) has been described for schizophrenia by Hogarty and Flesher.[33] It is a comprehensive program dealing with enhancing cognitive tasks of attention and memory and also enhancing social cognition using techniques of group activities and practice at dealing with real life situations. In a 2-year randomized control trial of CET in schizophrenia patient it was found to significantly enhance processing speed, neuro-cognition, and social cognition.[34] These traditional CETs can be made more comprehensive by incorporating a component of training aimed at enhancing emotion recognition to achieve a holistic approach in the management of schizophrenia. The training of affect recognition (TAR) is one such module that imparts training in affect recognition in patients with schizophrenia based on principles of errorless learning using computer-based tasks and group discussions.[35]

Yoga therapy is an ancient Indian system of alternative medicine with advantages of being cost effective, having better patient acceptability and resources for training being widely available.[36] In a developing country like India, where resources are sparse, yoga therapy can be a useful add-on modality of treatment. Earlier studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of add-on yoga therapy on negative symptoms in schizophrenia.[37] We attempted to study the effect of add-on yoga therapy on a larger sample of antipsychotic stabilized schizophrenia patients.[38] 66 patients were randomized to yoga therapy, exercise group or waitlist group. Yoga and exercise group received training in yoga and physical exercise respectively for a period of 1-month and then practiced at home for two more months. Assessment included PANSS, TRENDS, and socio-occupational functioning scale at baseline, 2nd month and 4th month. We found a beneficial effect of yoga therapy on TRENDS accuracy score, negative symptoms and socio-occupational functioning at 2nd month. The results of this study for the first time demonstrated a beneficial effect of add-on yoga therapy on FERD in antipsychotic stabilized schizophrenia patients in randomized controlled trial design. This beneficial effect of yoga was replicated in an independent sample and it was also demonstrated that the group receiving yoga therapy had a significant increase in plasma oxytocin levels which may in turn explain beneficial effect of yoga on emotion recognition abilities.[39]

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSION

Facial emotion recognition deficits have also been demonstrated in other psychotic disorder such as bipolar disorder. As described earlier emotional processing of threat-related emotions could be neurodevelopmental markers for schizophrenia with specific neurobiological correlates in the right prefrontal cortex. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorders have been described to have differential patterns of cerebral laterality.[40] Hence, differences in patterns of FERD and its relation to neurodevelopmental indicators such as laterality could possibly serve as diagnostic markers for these disorders. Demonstration of these deficits in first-degree relatives would provide validity to the endophenotypic nature of these deficits. Hence, future studies should focus on understanding diagnostic utility, endophenotypic validity, and clinical correlates of FERD in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Our knowledge on FERD has established these deficits to be one among the important deficits in schizophrenia. They are present in the antipsychotic naïve state and persist throughout the course of the illness and could also be endophenotypic markers for the disorder. These deficits also have important implications to further our understanding of the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Enhanced emotional threat perception is emerging as a hypothetical model to explain the evolution of psychopathology in schizophrenia and has been demonstrated to have specific underlying neurobiological correlates. FERD can be used as useful neurobehavioral probes in future studies involving functional imaging paradigms. These deficits are known to be associated with poorer socio-occupational functioning and hence are of important clinical relevance. Antipsychotics and nonpharmacological interventions have shown promise in improving FERD. The knowledge of the existence of these deficits has opened up newer avenues for treatment and provides hope for a better functional recovery in a disorder which is otherwise known to be one of the important causes of disability in the world. Schizophrenia has been classically described to have positive, negative, and cognitive symptom dimension. Emerging evidence strongly supports a fourth dimension of social cognitive symptoms with FERD representing a new face in our understanding of this complex disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to my mentors Dr. B. N. Gangadhar and Dr. Ganesan Venkatasubramanian, Department of Psychiatry, NIMHANS Bengaluru for their constant guidance and support in undertaking this work. I would like to acknowledge funding support provided by the Indian Council of Medical Research under the MD/MS thesis financial assistance scheme. The author is supported by Department of Science and Technology under Cognitive science initiative (SR/CSI/32/2011). I acknowledge Drs. Rashmi Arasappa and Nalini N. Reddy for helping me in carrying out this work. I am grateful to the study subjects who consented to take part in the assessments and the actors; whose images are used in TRENDS, for lending their talent for a scientific cause.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Brüne M. Emotion recognition, ‘theory of mind,’ and social behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grady CL, Keightley ML. Studies of altered social cognition in neuropsychiatric disorders using functional neuroimaging. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:327–36. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, et al. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: Intensity effects and error pattern. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1768–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brekke JS, Nakagami E, Kee KS, Green MF. Cross-ethnic differences in perception of emotion in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;77:289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elfenbein HA, Mandal MK, Ambady N, Harizuka S, Kumar S. Cross-cultural patterns in emotion recognition: Highlighting design and analytical techniques. Emotion. 2002;2:75–84. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:203–35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behere RV, Raghunandan VN, Venkatasubramanian G, Subbakrishna DK, Jayakumar PN, Gangadhar BN. TRENDS: A Tool for Recogniton of Emotions in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Indian J Psychol Med. 2008;30:32–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB. Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: A review. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:399–412. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van’t Wout M, van Dijke A, Aleman A, Kessels RP, Pijpers W, Kahn RS. Fearful faces in schizophrenia: The relationship between patient characteristics and facial affect recognition. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:758–64. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142cc31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC. Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: Association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:127–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucharska-Pietura K, David AS, Masiak M, Phillips ML. Perception of facial and vocal affect by people with schizophrenia in early and late stages of illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:523–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bediou B, Franck N, Saoud M, Baudouin JY, Tiberghien G, Daléry J, et al. Effects of emotion and identity on facial affect processing in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin F, Baudouin JY, Tiberghien G, Franck N. Processing emotional expression and facial identity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;134:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal MK, Jain A, Haque-Nizamie S, Weiss U, Schneider F. Generality and specificity of emotion-recognition deficit in schizophrenic patients with positive and negative symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 1999;87:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:1009–19. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Reddy N, Gangadhar BN. Effect of risperidone on emotion recognition deficits in antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia: A short-term follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MJ, Phillips ML. Social threat perception and the evolution of paranoia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Reddy NN, Gangadhar BN. First rank symptoms and facial emotion recognition deficits in antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia: Implications for social threat perception model. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: Implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:515–28. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Chan RC, McAlonan GM, Gong QY. Facial emotion processing in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging data. Schizophr Bull. 36:1029–39. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behere RV, Kalmady SV, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Orbitofrontal Lobe Volume Deficits in Antipsychotic-Naïve Schizophrenia: A 3-Tesla MRI study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2009;31:77–81. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.63577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Gangadhar BN. Enhanced Emotional Threat Perception and Right Cerebral Hemispheric Dysfunction in Antipsychotic Naive Schizophrenia. Paper Presented at th Biennial Australasian Schizophrenia Conference Sydney. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfeld AJ, Lieberman JA, Jarskog LF. Oxytocin, dopamine, and the amygdala: A neurofunctional model of social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:1077–87. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horan WP, Green MF, DeGroot M, Fiske A, Hellemann G, Kee K, et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia, Part 2: 12-month stability and prediction of functional outcome in first-episode patients. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:865–72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Gangadhar BN. Enhanced Emotional Threat Perception: A Neurodevelopmental Marker for Schizophrenia? Paper Presented at the 5th International Conference on Schizophrenia. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwood TA, Swerdlow NR, Gur RE, Cadenhead KS, Calkins ME, Dobie DJ, et al. Genome-wide linkage analyses of 12 endophenotypes for schizophrenia from the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:521–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kee KS, Green MF, Mintz J, Brekke JS. Is emotion processing a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:487–97. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behere RV. Dorsolateral prefrontal lobe volume and neurological soft signs as predictors of clinical social and functional outcome in schizophrenia: A longitudinal study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:111–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey PD, Patterson TL, Potter LS, Zhong K, Brecher M. Improvement in social competence with short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment: A randomized, double-blind comparison of quetiapine versus risperidone for social competence, social cognition, and neuropsychological functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1918–25. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Widmark C, Reist C, Erhart S, Braff DL, et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia: Relationships with neurocognition and negative symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:316–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbener ES, Hill SK, Marvin RW, Sweeney JA. Effects of antipsychotic treatment on emotion perception deficits in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1746–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shayegan DK, Stahl SM. Emotion processing, the amygdala, and outcome in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:840–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Practice principles of cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:693–708. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: Effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:866–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wölwer W, Frommann N. Social-cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: Generalization of effects of the Training of Affect Recognition (TAR) Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(Suppl 2):S63–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behere RV, Muralidharan K, Benegal V. Complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of substance use disorders – A review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28:292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia – A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behere RV, Arasappa R, Jagannathan A, Varambally S, Venkatasubramanian G, Thirthalli J, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on facial emotion recognition deficits, symptoms and functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:147–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayaram N, Varambally S, Behere RV, Venkatasubramanian G, Arasappa R, Christopher R, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on plasma oxytocin and facial emotion recognition deficits in patients of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(Suppl 3):S409–13. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rao NP, Arasappa R, Reddy NN, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Antithetical asymmetry in schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder: A line bisection study. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:221–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]