Abstract

Background:

Depression is the most common mental health problem in late-life. We need more information about the incidence and prevalence of major and minor syndromes of depression in older people. This will help in service development.

Aims:

To estimate the prevalence of depressive disorders among community resident older people in Kerala, India and to identify factors associated with late-life depression.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred and twenty community resident older subjects were assessed for depression by clinicians trained in psychiatry. They used a symptom checklist based on International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10) Diagnostic criteria for research for Depression and Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale for assessment of symptoms. A structured proforma was used to assess sociodemographic characteristics and medical history. The point prevalence of depression was estimated. Univariate analysis and subsequent binary logistic regression were carried out to identify factors associated with depression.

Results:

Prevalence of any ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) depressive episode was 39.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 32.6–45.9). There was significant correlation between depression and female gender (odds ratio [OR] 2.33; 95% CI 1.07–5.06) and history of a significant life event in the previous year (OR 2.39; 95% CI 1.27–4.49).

Conclusion:

High prevalence rate of late-life depression is indicative of high burden due to depression among older people in the community. Better awareness among primary care clinicians can result in better detection and management of late-life depression.

Keywords: Community resident elderly, depressive disorders, elderly, late-life depression

INTRODUCTION

Depression is the most common mental health problem in late-life. The reported prevalence of late-life depression varies widely, ranging from 10% to 55%.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] By far, there is no agreement about the factors associated with late-life depression.[9,10] This variability across studies could, at least in part, be due to the differences in assessments and case definition. Many studies use screening instruments in place of clinician interviews and rely only on cut-off scores to identify depression. This practice, often mandated by feasibility concerns, is a departure from the traditional reliance on clinical judgment for identifying syndromal depression and its sub-classification.

An episode of major depression can have many adverse downstream consequences for an older person. Presence of significant depressive symptoms in late-life could even predict the incidence of major depression.[11] Hence, early identification and prompt management of milder forms of depression could help in reducing the incidence of major depression. We need to have more information about the incidence and prevalence of both major and minor syndromes of depression in older people. Accurate estimates and a public health approach will help us to develop better services.

We set out to estimate the prevalence of depressive disorders among community resident older people in Kerala, India. Clinicians trained in psychiatry used assessments similar to that of clinical practice to diagnose depression. We also aimed to identify factors associated with late-life depression. This study was part of a public health initiative to improve community care for older adults in the local Grama Panchayath.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used a cross-sectional design to estimate the prevalence of depression. Sample size was calculated with an assumed prevalence of 20% for depression and a precision factor of five. The sample size needed was 246. A case-control design framework was used to identify possible risk factors of geriatric depression. The protocol of the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Government Medical College, Thrissur, Kerala, India.

The study was conducted in the Thalikulam Grama Panchayat of Thrissur district in Kerala from June 2011 to November 2011. The Government Medical College Thrissur had completed a health survey in Thalikulam Panchayat in association with a local Non-Governmental Organization (NGO). People above the age of 65 years were identified from this survey. There are 16 wards in the Panchayath, and we invited all residents older than 65 years from the wards 1, 2, and 3 to participate in the study. They were explained the aims of the study, procedure involved, and time required for participation. Consenting subjects were evaluated in the community at their homes or in their neighborhood by clinicians trained in psychiatry. Care was taken to ensure privacy. The local NGO assisted in scheduling and organizing the interviews.

Three consultant psychiatrists and a final year postgraduate trainee in psychiatry interviewed subjects, elicited history, and examined them. The following instruments were used for assessments: (i) Symptom checklist based on the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10) Diagnostic criteria for research for Depression,[12] (ii) Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),[13] and (iii) a structured proforma to assess sociodemographic characteristics and medical history. ICD-10 Research Diagnostic Criteria was used for diagnosis of depression. Cases were categorized to mild depression with and without the somatic syndrome, moderate depression with and without the somatic syndrome, severe depression with and without psychotic symptoms. Severities of depressive symptoms were measured using the MADRS. Clinician also documented the presence of other major psychiatric syndromes.

The sociodemographic data, medical history, and psychiatric diagnoses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Cases of mild depression with and without the somatic syndrome, moderate depression with and without the somatic syndrome, severe depression with and without psychotic symptoms were considered as cases of depression. Subjects with a diagnosis of adjustment disorder with depressive symptoms were not counted as cases while estimating the prevalence of depressive disorders. Point prevalence of depression among elderly was calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI).

The risk factors were classified into sociodemographic factors, psychological factors, and comorbid medical diseases. An examination of the various factors associated with depression was done by cross tabulation of determinants against the groups with and without depressive symptoms. Univariate analysis was done using Chi-square test to identify the risk factors associated with depression. The variables, which showed a significant association in this analysis were selected for multivariate analysis. Binary logistic regression was carried out to identify the most significant risk factors of depression. All the statistical analysis of the data was done using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) version 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Epi Info software version 3.5.3.

RESULTS

A total of 275 subjects were invited for the study, and we could recruit 220 subjects.

The overall response rate was 80%, and the reasons for nonresponse included unwillingness to participate, inability to cooperate for an interview, unavailability at home during the community visits, hospitalizations, change of residence, and death.

The subjects were predominantly females (n = 127, 57.7%) compared to males (n = 93, 42.2%). The majority of them (n = 156, 70.9%) were in the young old category (65–74 years). Of the total population, 118 (53.6%) subjects were married, and 102 subjects did not have a partner. 94 of the elderly (42.7%) were widowed, three were divorced or separated, and five were single. Half of the subjects (n = 110, 50%) lived with their spouse and children, 11 (5%) with their spouse, 92 (41.9%) with children or other relatives, and 7 (3.2%) lived alone. The literates in the population came to 77% (n = 171), 83.6% (n = 184) was unemployed, and 63.2% (n = 139) had no regular source of income. Substance dependence was reported in 20.9% (n = 46) of the population. Alcohol and tobacco were the substances abused by the population. Six of the subjects were dependent on alcohol and 35 had tobacco dependence. Five of the subjects had both alcohol and tobacco dependence.

Sixty-five of subjects (29.5%) reported to have experienced one or more significant adverse life events such as financial difficulties, interpersonal problems, and health-related issues in the past 1 year. Past history of mental illness was reported by 15 subjects (6.8%) and 10 of them had a previous history of depression. More than half of the elderly (n = 143, 65%) reported that they actively participated in household activities.

A total of 116 subjects (52.7%) were diagnosed cases of hypertension and 68 (30.9%) were known cases of diabetes mellitus. 31 (14.1%) subjects had a history of coronary artery disease and 12 (5.5%) had a history of cerebrovascular accident. Nineteen (8.6%) of the subjects were diagnosed cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 14 (6.4%) had dyslipidemia, and 40 (18.2%) had some form of musculoskeletal disorders.

Eighty-six older people were diagnosed to have depression, and the prevalence of any ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) depressive episode in our sample was 39.1% (95% CI 32.6–45.9). 18 older people had a severe depressive episode, giving it a prevalence rate of 8.2%. There were 33 (15%) subjects who had met criteria for the mild depressive episode while 35 (15.9%) had a moderate depressive episode. We also identified one case of generalized anxiety disorder, 12 cases of adjustment disorder with depressed mood, and three subjects with dementia among the study subjects.

The mean MADRS score for cases of depression was 21.4 (SD = 8.031). The mean MADRS score for subjects receiving an ICD-10 diagnosis of the mild depressive episode was 14.39, whereas it was 23.51 for moderate depressive episode, and was 30.11 for the severe depressive episode.

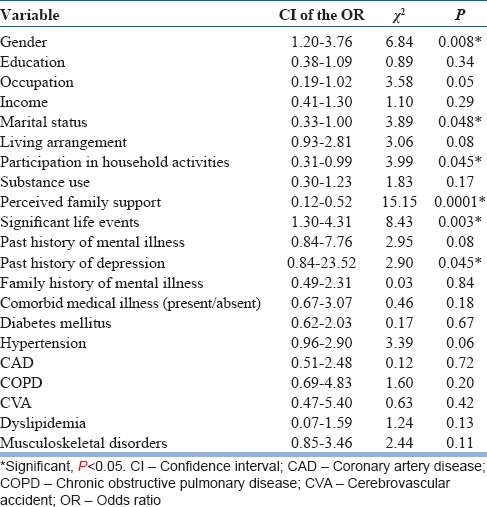

The risk factors were categorized into sociodemographic risk factors, psychological risk factors, and comorbid medical illnesses. Univariate analysis done using the Chi-square test [Table 1] showed association of depression with female gender, lack of a life partner, history of a significant life event in the past year, good family support, participation in household activities, and past history of depression. Results of further analysis using binary logistic regression showed significant correlation of depression with female gender (odds ratio [OR] 2.33; 95% CI 1.07–5.06; P = 0.0319); history of a significant life event in the past year (OR 2.39; 95% CI 1.27–4.49; P = 0.0069). Having good family support (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.12–0.59; P = 0.0011) and participation in household activities (OR 0.4604; 95% CI 0.24–0.85; P = 0.0148) were found to be protective. There was no correlation between comorbid medical illnesses and depression when analyzed as a single variable and as individual variables [Table 1].

Table 1.

Association of sociodemographic factors, psychosocial factors, and comorbid medical illnesses with depression

DISCUSSION

We found a prevalence rate of 39.1% of case level depression among community resident older people. Mild and moderate depression was common with a combined prevalence of 30.9% while severe depressive episode affected 8.2% of older people.

The high prevalence rate of late-life depression reported here is indicative of the high burden due to depression among older people in the community. We found the risk of depression to be twice as high for women when compared to men. This may be due to their increased life expectancy, poor social support or exposure to psychosocial stressors. The subjects who had a significant adverse event in the past year were at higher risk for depression. Participation in household activities was found to be protective, and this may indicate less functional impairment and disability. It is also possible that participation in household activities protects against social isolation and increases the self-esteem of older people. The behavioral activation associated with work may also be one of the reasons. We also found perceived family support to be a protective factor. Social support can be seen as an emotional reassurance, facilitator of formal and informal care which if accessed can reduce the impact of disease and disability in the elderly.

Previous community-based studies on depression from India had reported variable rates of depression, probably due to the differences in methodology.[14,15,16,17] Assessment in these studies was done using short screening questionnaires or by a nonpsychiatric professional. This could have resulted in the under reporting of depressive symptoms.

Most of these studies have been done more than a decade ago. It is possible that the nature of stressors, coping abilities, and support systems available to elderly have changed. Subjects would be comfortable and more communicative about their depressive symptoms when interviewed by a clinician than while reporting symptoms, while responding to a questionnaire.

The increased risk of late-life depression in females has been established in other community studies.[9,18,19] In rural societies where gender inequality adversely affects women, living without a male partner can particularly be stressful in old age. The pattern of dependency, which is built into the framework of the social structure could lead to a sense of helplessness in widowed women, putting them at higher risk for late-life depression. The finding that the occurrence of a significant life event in the past year increases the risk of depression is consistent with that of Murphy[20] but not in keeping with the findings of Barnes Nacoste and Wise.[21] We found participation in household activities to be protective against late-life depression like others.[9,10] The protective effect of good family support has also been demonstrated earlier.[22,23] Interestingly, we did not find medical comorbidities to be associated with depression, unlike other reports.[24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] However, most of those studies were done on subjects who had sought help for physical morbidity. Our subjects were not selected based on any prior service contact and represent older people living in the community. The general acceptance of comorbidity as part and parcel of late-life by rural societies could also be one reason.

We recruited about 10% less than the estimated sample size. We relied only on the perceptions of older persons and family members about their disability and past significant life events and did not use any objective measures, which is a limitation. The strengths of the study include the low refusal rate and interviews by clinicians trained in psychiatry, to identify cases of depression in this community sample. This allows valid and precise estimates of various sub-categories of depression in the study sample. We used ICD-10, which has advantages over Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition in identifying milder forms of depression.[36]

The reported high prevalence of depression among older people has important public health implications for Kerala, a state, which is witnessing rapid demographic aging. There is a well-established primary health care system in the state. Most cases of depression, identified by us during the course of this study were not getting treatment for depression even though they were in contact with primary care clinicians for managing medical illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension. Better awareness among primary care clinicians can result in better detection of cases and their management.

It is well-known that depression adversely impacts the quality of life of the older person and outcome of comorbid medical illnesses. Persistence of depressive symptoms may predict the risk for an episode of major depression. Late-life depression affects a significant proportion of community resident older people and they need help. There is a strong case to upgrade the knowledge and skill of primary care doctors to diagnose and treat depression in patients seeking their help.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the staff of Thalikulam Vikas Trust, Thalikulam (a NGO) for their support and help in scheduling and organizing the interviews of the subjects in the community.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Senthilkumar P, Gayathri K, Prince M, Jacob KS. Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:372–8. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerra M, Ferri CP, Sosa AL, Salas A, Gaona C, Gonzales V, et al. Late-life depression in Peru, Mexico and Venezuela: The 10/66 population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:510–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steffens DC, Fisher GG, Langa KM, Potter GG, Plassman BL. Prevalence of depression among older Americans: The Aging, Demographics and Memory Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:879–88. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherina MS, Rampal L, Mustaqim A. The prevalence of depression among the elderly in Sepang, Selangor. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi I, Yip PS, Chiu HF, Chou KL, Chan KS, Kwan CW, et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlates in Hong Kong's Chinese older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:409–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai YF, Yeh SH, Tsai HH. Prevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elders in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:1097–102. doi: 10.1002/gps.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khattri JB, Nepal MK. Study of depression among geriatric population in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8:220–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y, Sasaki H, Yamaji M. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and related risk factors for depressive symptoms among elderly persons living in a rural Japanese community: A cross-sectional study. Community Ment Health J. 2007;43:583–90. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–56. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prince MJ, Harwood RH, Thomas A, Mann AH. A prospective population-based cohort study of the effects of disablement and social milieu on the onset and maintenance of late-life depression. The Gospel Oak Project VII. Psychol Med. 1998;28:337–50. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Cuijpers P, Patel V, Cohen A, Dias A, Chowdhary N, et al. Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:123–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao AV, Madhavan T. Gerospsychiatric morbidity survey in a semi-urban area near madurai. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:258–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkobarao A. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1990. Health Care of the Rural Aged 1984-88: A Report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramachandran V, Menon MS. Depressive disorder in late life. In: Venkobarao A, editor. Depression. Madurai: Vaigai Achagam; 1980. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhillon PK. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company; 1992. Psycho-Social Aspects of Aging in India. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong MY, Tsang HY, Chen CS, Tang TC, Chen CC, Yeh TL, et al. Community study of depression in old age in Taiwan: Prevalence, life events and socio-demographic correlates. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:29–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg T, Smit JH, Hooijer C, van Tilburg W. Major and minor depression in later life: A study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 1995;36:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy E. Social origins of depression in old age. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:135–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes Nacoste DR, Wise EH. The relationship among negative life events, cognitions, and depression within three generations. Gerontologist. 1991;31:397–403. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner RJ, Turner JB. Social integration and support. In: Aneshensel C, editor. Hand Book of Sociology of Mental Health. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. pp. 301–19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blazer DG, Moody-Ayers S, Craft-Morgan J, Burchett B. Depression in diabetes and obesity: Racial/ethnic/gender issues in older adults. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:913–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER, Dew MA, Rogers JC, Whyte EM, et al. Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: Implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyles KW. Osteoporosis and depression: Shedding more light upon a complex relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:827–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams SA, Kasl SV, Heiat A, Abramson JL, Krumholz HM, Vaccarino V. Depression and risk of heart failure among the elderly: A prospective community-based study. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:6–12. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glassman AH, Shapiro PA. Depression and the course of coronary artery disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:4–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:580–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson RG, Price TR. Post-stroke depressive disorders: A follow-up study of 103 patients. Stroke. 1982;13:635–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel D. Cancer and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;30:109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schleifer SJ, Macari-Hinson MM, Coyle DA, Slater WR, Kahn M, Gorlin R, et al. The nature and course of depression following myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1785–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression following myocardial infarction. Impact on 6-month survival. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;270:1819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L. Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: A meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2010;39:23–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, Leiby BE, Tasman WS. Preventing depression in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:886–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito M, Iwata N, Kawakami N, Matsuyama Y, Ono Y, et al. World Mental Health Japan-Collaborators. Evaluation of the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for depressive disorders in a community population in Japan using item response theory. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19:211–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]