Abstract

Background:

Several Western countries have established mother-baby psychiatric units for women with mental illness in the postpartum; similar facilities are however not available in most low and medium income countries owing to the high costs of such units and the need for specially trained personnel.

Materials and Methods:

The first dedicated inpatient mother-baby unit (MBU) was started in Bengaluru, India, in 2009 at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences in response to the growing needs of mothers with severe mental illness and their infants. We describe the unique challenges faced in the unit, characteristics of this patient population and clinical outcomes.

Results:

Two hundred and thirty-seven mother-infant pairs were admitted from July 2009 to September 2013. Bipolar disorder and acute polymorphic psychosis were the most frequent primary diagnosis (36% and 34.5%). Fifteen percent of the women had catatonic symptoms. Suicide risk was present in 36 (17%) mothers and risk to the infant by mothers in 32 (16%). Mother-infant bonding problems were seen in 98 (41%) mothers and total breastfeeding disruption in 87 (36.7%) mothers. Eighty-seven infants (37%) needed an emergency pediatric referral. Ongoing domestic violence was reported by 42 (18%). The majority of the mother infant dyads stayed for <4 weeks and were noted to have improved at discharge. However, 12 (6%) mothers had readmissions during the study period of 4 years. Disrupted breastfeeding was restituted in 75 of 87 (86%), mother infant dyads and mother infant bonding were normal in all except ten mothers at discharge.

Conclusions:

Starting an MBU in a low resource setting is feasible and is associated with good clinical outcomes. Addressing risks, poor infant health, breastfeeding disruption, mother infant bonding and ongoing domestic violence are the challenges during the process.

Keywords: India, low- and middle-income countries, mother-baby unit, perinatal psychiatry, postpartum psychosis

INTRODUCTION

The joint admission of infants with mentally ill mothers was pioneered by Thomas Main in 1948 at the Cassel Hospital in Surrey, England.[1] The initial joint admissions were limited to patients with neuroses but slowly progressed to include severe mental illnesses in facilities across the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence clinical guidelines for antenatal and postnatal mental health recommend that women who need inpatient care for a mental disorder within 12 months of childbirth should normally be admitted to a specialized mother-baby unit (MBU) facility, unless there are specific reasons to the contrary.[11]

Mother-baby unit is an inpatient psychiatry service with at least four beds that are separate from other wards with a facility for joint admission of the mother along with the baby. They are staffed 24-h a day, 7 days a week, by dedicated multidisciplinary staff to care for both mothers and babies.[6] MBUs encourage breastfeeding, are expected to have specific interventions for parenting, provide psychotherapy, enhance mother-infant bonding and offer an opportunity for education regarding the current illness and preventing future episodes. They are also expected to provide support to spouses and caregivers and also involve social services in case of risk to the infant.[7] Admission to an MBU enables a mother to obtain care for psychiatric disorders and simultaneously receive support in developing her identity as a mother. This care is meant to prevent attachment disorders and mother-baby separation.

Most of the data available from countries such as UK, France, Belgium, Australia indicate that 75–80% of mothers have a good outcome.[8,12,13,14,15]

Lack of dedicated MBUs may result in separation from infants causing mothers to refuse admission, problems with breastfeeding, difficulties in diagnostic evaluation, lack of dyadic psychotherapy, longer lengths of hospital stay, increased chances of relapse after discharge, and increasing the responsibility of caring for the baby on the spouse and extended family.[14]

There are no published reports on dedicated MBU facilities from low- and middle-income (LAMI) countries. LAMI countries have high birth rates and postpartum psychiatric disorders often present with co-morbid organic and medical conditions necessitating specialized care,[16] enhancing the need for special facilities during this period.

This study reports a description of the clinical profile, interventions and outcomes of joint mother-infant admissions at a newly established MBU in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the mother-baby unit

The first MBU in India was started in July 2009 at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru as a five bedded facility for admitting mother-infant dyads.

Staffing

The unit is managed by a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, and nurses. One psychiatry trainee is posted to the unit round the clock and social work and psychology trainees provide part-time services. A lactation expert is available on call to respond to breastfeeding difficulties, and pediatric support is available from a neighboring pediatric hospital.

Admission procedure

All mother-infant dyads are first assessed by the team for their suitability to admission under MBU facility. This assessment includes risk assessment using an instrument – Formal Initial Risk Assessment for Mothers And Babies (FIRST-MB) (for self harm and harm to the infant)[17] infant health details, ruling out medical conditions in the mother and assessing problems related to breastfeeding.

Based on the risks, necessary decisions are made about joint admissions, with precautions to ensure the safety of mother and the infant. Mothers and infants are admitted with a family member (usually a woman) in keeping with local cultural traditions where a postpartum mother receives extra care from the family and is seldom left alone. Babies have cribs based on their age, and the caregiver has facilities to rest near the mother-infant dyad.

Referrals

All infants are referred to a neighboring pediatric hospital for consultation about feeding and immunization. Twice weekly psycho-education sessions are conducted by the psychology and social work trainees who also do specific interventions for impaired mother-infant bonding (including video enabled interventions to promote bonding). Once a week group sessions are held for caregivers and spouses focusing on caregiver burden and relapse prevention strategies. An infection control nurse advices mothers and caregivers on personal and infant cleanliness and ward hygiene.

Data collection

Tools used

Data for this paper have been collected prospectively and includes socio-demographic and clinical details; history of domestic violence and infant details (overall health, immunization, and infant feeding) and clinical and mother-infant outcomes at discharge.

Detailed socio-demographic data were collected, and the FIRST-MB tool was used to assess; risks to mother and infant.[17] The tool has 10 items, which include risk to self, risk to others, risks to infant, medical conditions, feeding concerns, and infant health.

Psychiatric diagnosis was established by two trained psychiatrists as per the ICD-10 classification.[18] Items from the Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health were used to collect clinical details of pregnancy and postpartum mental health.[19] Using the Kannada translation of the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ)[20] subjective mother-infant bonding was assessed. The PBQ is a self-report questionnaire with positive and negative statements related to the infant and is rated by mother on a Likert scale.

The Objective Bonding Instrument was used to assess maternal infant safety, psychotic ideas about the baby, maternal care toward the baby, and other aspects of maternal behavior toward the infant based on family and nurses observations.[21] The bonding assessments were done at admission and discharge. Details of lactation and infant feeding were also assessed systematically at admission and discharge.

RESULTS

The total number of admissions from July 2009 to September 2013 was 237. The mean age was 24.25 ± 4.27 years and mean years of education were 6.50 ± 3.02. Most women were from lower socio-economic status and rural backgrounds. The majority of the mothers (80%) stayed for 3–4 weeks and the mean duration of hospital stay was 17.23 ± 14.56 days. One hundred and twelve women (47%) were primiparous, 27 (11%) had pregnancy related complications and 42 (18%) had undergone cesarean section. One hundred and ninety-three women (81%) had their mothers staying with them in the MBU while 11 (5%) had a spouse, 11 (5%) had a sibling, and 18 (8%) had other family members.

Illness details

Eighty-six mothers (36.2%) had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (manic episode), 82 (34.5%) had acute and transient psychosis, 32 (14%) had a depressive disorder, 15 (6%) had schizophrenia, and 16 (7%) had conditions such as severe obsessive compulsive disorders, dissociative disorders, and personality disorders. Three mothers were admitted for a primary mother-infant bonding disorder, which was independent of the psychiatric problem. Co-morbid medical and organic conditions were seen in 45 (19%) women, and catatonia was the presenting clinical picture in 36 (15%). Suicide risk was seen in 36 (15%), risk to infant in 32 (14%) and infant related psychotic symptoms in 40 (17%). Ongoing physical violence by the intimate partner was reported in 42 (18%) of mothers.

Infant health and breastfeeding

One hundred and twenty-eight (54%) infants were <8 weeks of age at the time of admission, 88 (37%) were between 8 weeks and 6 months of age, and 21 (8%) were between 6 months and 1-year-old.

Eighty-seven (37%) infants needed a referral to a pediatrician for specific advice. Forty-five infants for gastrointestinal infections, 5 for specific feeding advice, 25 for lack of any immunization, and 12 for other medical reasons such as skin problems and febrile illnesses.

Breastfeeding had been completely stopped owing to maternal illness in 87 (36%) mothers while 150 mothers were breastfeeding at least partially at the time of admission.

Risk assessments

The FIRST-MB detected risks in 68 (28%) mothers. Harm toward themselves and suicidality in 18; harm toward the infant in 14; and harm toward self, infant, and others in 36 mothers. Ten mothers had to be refused admission to the MBU initially, as there was a serious risk to infant from the mother and were provided care at a different ward separated from the infant. However, these mothers were shifted to MBU with their infant once the high-risk status was improved.

Treatment related details

All mothers received psychotropic medications as indicated and included second generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines. Sixty-eight women (28%) received electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) for catatonia, high suicidal risk, and need for rapid symptom control.

Mother-infant bonding and interventions

Based on ratings of PBQ and Objective Bonding instrument, mother-infant bonding problems that needed specific interventions were noted in 98 (40%) of the mothers.

Interventions for mothers with severe bonding disorders included a six session video enabled intervention.[22] In addition, all mothers received six sessions of mother-infant bonding education that focused on maintaining eye to eye contact, cooing, singing lullabies, smiling at the infant, infant massage and stroking, restitution of breastfeeding, understanding cues from baby (hunger, sleep etc.), and playing with the baby. Among 98 dyads who needed mother-infant bonding interventions, ratings of PBQ and Objective Bonding at discharge were indicative of normal bonding in 88 mothers. Ten mother-infant dyads needed close supervision or surrogate infant care even at the time of discharge.

Lactation interventions

These included dispelling myths, helping in positioning while feeding and education regarding timing of breastfeeding based on peak levels of psychotropic drugs in breast milk. The use of electronic breast pumps and use of expressed breast milk for infants was encouraged when mothers had difficulty in feeding due to sedation, agitation, or when they received ECTs. Advice from a lactation expert was sought for women who had severe feeding difficulties. Of the 87 mothers who had stopped breastfeeding due to mental illness, lactation was restored in 75 (86%).

Outcomes and re-admissions

Among the 237 mothers, 188 (80%) were noted to have improved completely while the rest had some residual symptoms at discharge. However, 12 (6%) of the 237 mothers had readmissions to the unit during the study period of 4 years. Eight of the twelve readmissions were due to a psychosis developing after a subsequent childbirth with inadequate psychiatric care during pregnancy and poor treatment compliance. In 5 of the 12 readmissions, significant social stress and marital problems were responsible for poor treatment compliance.

DISCUSSION

The findings from our MBU highlight some of the cultural and resource challenges that are likely to be faced by future MBU facilities in other identical settings. An important difference between MBUs and other inpatient units is the need to establish assessments and interventions aimed at the joint care of the mother and infant dyad. This includes both clinical management, infant health, and handling of mother-infant interactions.

The clinical profile of patients admitted to our unit while similar in some aspects to those reported by MB units around the world, also has some important differences. The similarities included brief duration of stay, good clinical outcomes, and low rates of readmission; similar to those reported from the UK and Europe.[15,23,24] The important difference between our sample and those from the West, however, was in the rates of acute psychosis and catatonia. Higher rates of acute psychosis in our sample maybe due to organic factors. It may also be indicative of a subsequent bipolar illness, which is known to be the most common form of postpartum psychosis.[25] The high rates of catatonia (15%) may be related to comorbid medical illnesses and nutritional deficiencies.[10,16,26]

Infants are an important part of the joint admission, and care of the vulnerable infant is an important role of an MBU. The majority of our infants were below 8 weeks of age which is similar to findings from MBUs across the world. As MBUs admit very young infants, there is a strong need for pediatric support services, as shown by our high rates of referral.[27] An additional concern in LAMI countries such as India, where hygiene is a concern and artificial feeding expensive, is the disruption of breastfeeding when a mother has a postpartum psychiatric illness. Mother-baby psychiatric units have an important role in restitution of lactation, which is important for infant health and for mother-infant bonding. The finding that specific lactation interventions and advice led to the restitution of breastfeeding among mother-infant dyads in our MBU, where there was complete disruption (75 of 87 mother-infant dyads) emphasizes the need for such units.

Our finding of high levels of risk also strongly corroborate the need for assessment of mother-infant risks in MBUs.[3,6,7,8,28] Training doctors and nurses to assess risks systematically using a standard tool like the FIRST-MB, is an important method of assuring that risks are not neglected in this vulnerable period.[14]

In our setting, having a family caregiver helped in handling challenges related to infant safety and also in caring for the infant when the mother was disturbed, drowsy or needed ECTs. No infant was separated from the mother at discharge, which is contrary to the existing literature from the West where separation and foster care due to the risk associated with mental illness are not uncommon.[7,26,29,30,31] This is again a strength of the strong family system in India where surrogate care is often provided to the infant by female relatives.

Apart from the clinical challenges, social issues such as poverty and domestic violence are some of the other problems that MBUs like ours in LAMI countries might face. Rates of partner violence in pregnancy and postpartum are quite high, and MBU staff needs to be trained in assessing and managing the consequences of partner violence and providing appropriate interventions.[32,33]

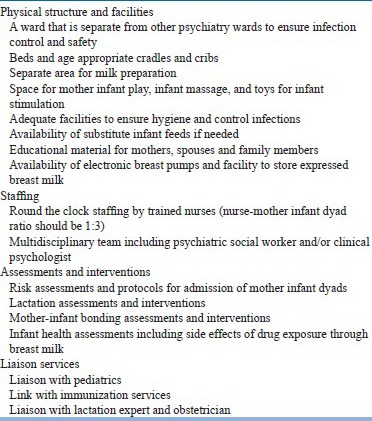

Box 1 lists the important requirements of a mother-baby inpatient psychiatry unit for future initiatives in LAMI countries.

Box 1.

The requirements of a mother-baby psychiatry inpatient unit

CONCLUSION

The NIMHANS mother-baby psychiatry unit is the first such inpatient facility in India, and while modeled after MBUs in the UK, has been adapted to be compatible with Indian systems of care during the postpartum period. Frequent co-morbid medical conditions in the mother and poor infant health highlight the need for adequate pediatric and medical/obstetric supportive services. Risk assessment and a quick response to this risk, forms an important part of multidisciplinary management. Bonding interventions remain an important part of MBU care, in addition to restitution or maintenance of lactation.

Mother-baby psychiatric units and services are a need in LAMI countries and our experience indicates that it is feasible to have an effective service that contributes to good clinical outcomes for the mother with mental illness and to mother-infant dyadic relationships.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Brockington IF. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. Motherhood and Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R. Paris, La Sorbonne: Journées biannuelles des unités mère-bébé; 1997. Evolution of psychiatric services for mentally ill childbearing women. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar R, Marks M, Platz C, Yoshida K. Clinical survey of a psychiatric mother and baby unit: Characteristics of 100 consecutive admissions. J Affect Disord. 1995;33:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)00067-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker AA, Morison M, Game JA, Thorpe JG. Admitting schizophrenic mothers with their babies. Lancet. 1961;2:237–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)90357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meltzer-Brody S, Brandon AR, Pearson B, Burns L, Raines C, Bullard E, et al. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17:107–13. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkin A, Gilburt H, Slade M, Lloyd-Evans B, Gregoire A, Johnson S, et al. A National Survey of Psychiatric Mother and Baby Units in England. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:629–33. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard L, Shah N, Salmon M, Appleby L. Predictors of social services supervision of babies of mothers with mental illness after admission to a psychiatric mother and baby unit. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:450–5. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0663-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM. Mother-Baby psychiatric units (MBUs): National data collection in France and in Belgium (1999-2000) Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joy CB, Saylan M. Mother and baby units for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD006333. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meltzer-Brody S, Brandon AR, Pearson B, Burns L, Raines C, Bullard E, et al. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17:107–13. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0390-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance. NICE guidelines [CG45]. February, 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Jun 22]. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG45/Guidance . [PubMed]

- 12.Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Howard LM, Sutter-Dallay AL. Treatment-mother - infant inpatient units. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salmon MP, Abel K, Webb R, Warburton AL, Appleby L. A national audit of joint mother and baby admissions to UK psychiatric hospitals: An overview of findings. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wisner KL, Jennings KD, Conley B. Clinical dilemmas due to the lack of inpatient mother-baby units. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:479–93. doi: 10.2190/NFJK-A4V7-CXUU-AM89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Sutter AL, Thieulin AC, Dagens-Lafont V, Zimmermann MA, Debourg A, et al. Inpatient mother-and-child postpartum psychiatric care: Factors associated with improvement in maternal mental health. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndosi NK, Mtawali ML. The nature of puerperal psychosis at Muhimbili National Hospital: Its physical co-morbidity, associated main obstetric and social factors. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:41–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra PS, Saraf G, Desai G, Harish T, Reddy D, Gandi S. Detecting and managing risk to mother and infant in a mother-baby unit in India using a tool – The FIRST MB (Formal Initial Risk Assessment for Mothers and Babies. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:371–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1992. World Health Organisation. ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brockingon IF, Chandra P, George S, Hofberg K, Lanczik MH, Loh CC, et al. 5th ed. Birmingham, United Kingdom: Eyre Press; 2006. The Birmingham Interview for Maternal Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brockington IF, Oates J, George S, Turner D, Vostanis P, Sullivan M, et al. A screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2001;3:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra PS, Bhargavaraman RP, Raghunandan VN, Shaligram D. Delusions related to infant and their association with mother-infant interactions in postpartum psychotic disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:285–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy PD, Desai G, Hamza A, Karthik S, Ananthanpillai ST, Chandra PS. Enhancing mother infant interactions through video feedback enabled interventions in women with schizophrenia: A Single Subject Research Design Study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36:373–7. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.140702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard LM, Thornicroft G, Salmon M, Appleby L. Predictors of parenting outcome in women with psychotic disorders discharged from mother and baby units. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:347–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganjekar S, Desai G, Chandra PS. A comparative study of psychopathology, symptom severity, and short-term outcome of postpartum and nonpostpartum mania. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:713–8. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudron LH, Pies RW. The relationship between postpartum psychosis and bipolar disorder: A review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1284–92. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai JY, Huang TL. Catatonic features noted in patients with post-partum mental illness. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:157–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2003.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Sutter-Dallay AL, Thieulin AC, Dagens V, Zimmermann MA, Debourg A, et al. Predictors of infant foster care in cases of maternal psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:553–61. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buist A, Minto B, Szego K, Samhuel M, Shawyer L, O’Connor L. Mother-baby psychiatric units in Australia - The Victorian experience. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:81–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenny M, Conroy S, Pariante CM, Seneviratne G, Pawlby S. Mother-infant interaction in mother and baby unit patients: Before and after treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salmon MP, Abel K, Cordingley L, Friedman T, Appleby L. Clinical and parenting skills outcomes following joint mother-baby psychiatric admission. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitmore J, Heron J, Wainscott G. Predictors of parenting concern in a Mother and Baby Unit over a 10-year period. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:455–61. doi: 10.1177/0020764010365412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varma D, Chandra PS, Thomas T, Carey MP. Intimate partner violence and sexual coercion among pregnant women in India: Relationship with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard LM, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, Feder G. Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]