Abstract

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders of B and T cell origin that are treated with chemotherapy drugs with variable success rate that has virtually not changed over decades. Although new classes of chemotherapy-free epigenetic and metabolic drugs have emerged, durable responses to these conventional and new therapies are achieved in a fraction of cancer patients, with many individuals experiencing resistance to the drugs. The paucity in our understanding of what regulates the drug resistance phenotype and establishing a predictive indicator is, in great part, due to the lack of adequate ex vivo lymphoma models to accurately study the effect of microenvironmental cues in which malignant B and T cell lymphoma cells arise and reside. Unlike many other tumors, lymphomas have been neglected from biomaterials-based microenvironment engineering standpoint. In this study, we demonstrate that B and T cell lymphomas have different pro-survival integrin signaling requirements (αvβ3 and α4β1) and the presence of supporting follicular dendritic cells are critical for enhanced proliferation in three-dimensional (3D) microenvironments. We engineered adaptable 3D tumor organoids presenting adhesive peptides with distinct integrin specificities to B and T cell lymphoma cells that resulted in enhanced proliferation, clustering, and drug resistance to the chemotherapeutics and a new class of histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), Panobinostat. In Diffuse Large B cell Lymphomas, the 3D microenvironment upregulated the expression level of B cell receptor (BCR), which supported the survival of B cell lymphomas through a tyrosine kinase Syk in the upstream BCR pathway. Our integrin specific ligand functionalized 3D organoids mimic a lymphoid neoplasm-like heterogeneous microenvironment that could, in the long term, change the understanding of the initiation and progression of hematological tumors, allow primary biospecimen analysis, provide prognostic values, and importantly, allow a faster and more rational screening and translation of therapeutic regimens.

Keywords: Lymphoma, B cell, T cell, Integrins, Hydrogels, Organoids, Panobinostat

1. Introduction

Malignant B and T cells form a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative diseases, collectively called lymphomas, which arise predominantly in the lymphoid tissues during the course of normal development and immune response [1–9]. The most common form of lymphomas, Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (NHLs), can originate from T cells, or more frequently, from B cells. The majority of B cell lymphomas originate from antigen-activated B cells in functional sub-anatomical structures, such as germinal centers in the spleen and lymph nodes, in which B cells undergo massive proliferation, DNA mutation of immunoglobulin genes, and clonal selection to eventually differentiate into antibody secreting cells, thus providing immunity against infections. In the rare event that DNA mutation is mistargeted to oncogenes, such as B cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) protein, a B cell lymphoma could arise [7,10].

Despite a better understanding of the NHL biology, the core of the treatment remains an empirical combinatorial chemotherapy regimen CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin (vincristine), and Prednisone) that has virtually not changed over decades, other than the addition of a monoclonal antibody against CD20 to the cocktail. One of the biggest roadblocks in developing new drugs is the inadequacy of testing models. Pre-clinical research in NHL has relied on testing compounds with suspension cultures of human lymphoma cell lines, without taking into account the lymphoid niche in which these tumors arise and reside [11]. This traditional approach for drug testing risks losing potential useful compounds by considering them as ineffective due to the conditions of the assays. This is the case for compounds with a mechanism of action that relies on suppressing survival signals from microenvironmental cues, such as integrin inhibitors. Integrins are transmembrane proteins that mediate cell–cell and cell–stroma interactions and are involved in survival and chemo-resistance of lymphoid malignancies, as we recently demonstrated for the integrin αVβ3 [12]. Equally problematic, standard 2D cultures could also overestimate the killing capacity of certain compounds, like chemotherapy agents due to the lack of “protective” microenvironmental conditions.

The crosstalk between lymphoma cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) via integrin molecules is important for their survival and chemo-resistance [13,14]. Our recent findings have demonstrated the role of integrin signaling in patient-derived T cell lymphoma survival and progression, in vitro and vivo. Specifically, in these studies, knockdown or pharmacologic inhibition of the integrin αvβ3 abrogated the proliferation of malignant T cells in vitro and in patient-derived xenograft mice models, an effect partially mediated by defective angiogenesis [12]. Given the increasing importance of the ECM and stromal microenvironment to NHL biology [15,16] and drug response [17], there is a need to develop 3D tissues that mimic the diseased lymphoid microenvironment and are adaptable to disease-specific needs. However, unlike most other tumors such as breast cancer and lung cancer, B and T cell lymphomas have been neglected from the biomaterials-based microenvironment engineering standpoint. Recent approaches to study 3D lymphoma structures have utilized cell aggregates using hanging drop methods [18] and polystyrene scaffolds [19] for lymphomas. However, these systems are unable to provide the necessary ECM-mediated integrin signaling and lack the porosity and mechanical properties of a soft lymphoid organ from which lymphomas arise. For solid tumors, hydrogels have been widely utilized as 3D microenvironments due to their ECM-like biophysical properties and cells encapsulated within naturally-derived ECM such as Matrigel [20–22] and collagen [23] have been reported. While these models provide a nourished 3D microenvironment, they have fundamental limitations such as batch-to-batch variability and limited design flexibility to meet the need for culturing different types of tumor cells with patient variability – as is the case with lymphomas, with more than thirty distinct entities [11]. In addition, tumors undergo microarchitectural remodeling through proteases (e.g. matrix metalloproteinase) [24,25] and therefore, synthetic scaffolds like poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and polystyrene are inadequate to allow cell mediated remodeling of the scaffolds. To overcome the limitations of ECM-derived hydrogels, there has been increased focus on developing synthetic hydrogels from natural and synthetic polymers, such as hyaluronic acid and polyethylene glycol, functionalized with bio-adhesive ligands and protease degradable cross-linkers.

In the current study, we demonstrate differential expression of integrin αvβ3 and α4β1 across B and T cell lymphomas. These findings emphasize the importance of integrin and tumor matrix signaling in lymphomas that inspired us to engineer a modular biomaterials-based lymphoid organoid presenting integrin ligands specific for the lymphoma tumor subtype. The biomaterial for our lymphoma tumor organoids was chosen to allow simple conjugation of integrin specificities with fast cross-linking, without the use of cytotoxic free-radicals and UV light. Specifically, we used our established PEG maleimide click chemistry hydrogels [26] that permits hydrogel functionalization with precise integrin density and specificity using a thiolated bio-adhesive peptide. These hydrogels crosslink under physiological conditions using an enzymatically degradable di-thiolated peptide cross-linker (allowing for matrix degradability). In addition, these organoids also incorporate follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) as supporting stromal cell subtype. Here we provide a lymphoid tissue mimicking 3D organoid system to culture B and T cell lymphoma cell lines in conditions that recapitulate the natural microenvironment of these lymphomas and is suitable for drug efficacy studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Polymers, peptides and drug-like compounds

Maleimide functionalized 4-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG-MAL) (20,000 Da, 99% functionalized) was purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. Integrin specific peptides, integrin αvβ3 binding RGD (NH2-GRGDSPC-COOH), integrin α4β1 binding REDV (NH2-GREDVGC-COOH) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 and 9 degradable peptide (NH2-GCRDVPMSMRGGDRCG-COOH) were purchased from AAPPTec, LLC with above 95% purity (bold represents target sequence). Doxorubicin was purchased from Sigma and Panobinostat was purchased from Selleck Chemicals.

2.2. Human B and T cell lymphoma lines

Human tonsil-derived FDCs HK and human Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cell HBL-1, were cultured with RPMI 1640 media, and supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Glutamax, 10 mM HEPES buffer and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human T cell lymphoma HuT-78 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and OCI-Ly12 was obtained from the Ontario Cancer Institute, Canada. Human B cell lymphoma OCI-Ly10 was obtained from the Ontario Cancer Institute, Canada; DoHH2, WSU-DLCL-2, SUDHL-4 and SUDHL-6 were obtained from the DMSZ (The Leibniz Institute DSMZ - German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH); and SC-1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. OCI-Ly10, OCI-Ly12 and HuT-78 were cultured with Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s media (IMDM) containing 20% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Suspension lymphoma cell lines were subsequently cultured in 20% of the conditioned media. The antibodies used in various studies include Anti Human IgM (clone SA-DA4, Southern Biotech); Anti Human IgM – APC (SA-DA4), Anti Human CD20 – FITC (2H7), Anti Human CD19 – PerCP-Cy5.5 (HIB19), Anti Human CD2 – APC (RPA-2.10), Anti Human CD49d – PE (9F10), and Anti Human CD29 – APC (TS2/16), all purchased from eBiosciences. FITC - Annexin V was obtained from Biotium.

2.3. Organoid fabrication and lymphoma co-culture

Synthetic hydrogel organoids of malignant B and T cell tumors were biofabricated using PEG-MAL and thiolated cross-linkers. In brief, PEG-MAL macromers were first conjugated with thiolated cell adhesive peptides RGD or REDV (peptide: PEG-MAL 1:4). Malignant B and T cells with or without FDCs were re-suspended in PEG-MAL macromer solution immediately before PEG-MAL was cross-linked with di-thiolated cross-linkers. MMP-9 degradable peptide VPM or non-degradable Di-thiothreitol (DTT) was used as a cross-linker at the volume ratio of 4:1 (polymer-cell: cross-linker). After mixing the macromer and cells, 10 μL droplet of polymer-peptide-cell mixture was placed into a well of a non-treated 96 well plate, and cured for 15 min at 37 °C in an incubator for complete gelation. Fresh media supplemented with 20% lymphoma conditioned media was added to the organoid culture and half of the media was replenished every 2 days.

2.4. Fluorescent and confocal microscopy

To examine the survival and clustering of the FDCs in the 3D organoids, 6000 HK cells (referred to as FDC henceforth) were encapsulated into PEG-MAL organoids functionalized with RGD, REDV, or no ligand and crosslinked with VPM peptide or DTT. Encapsulated FDC cells were stained with Calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer I for live/dead analysis and imaged with a Nikon TE2000U Inverted Scope on day 2. To observe the survival and morphology of the lymphoma cells, HBL-1 cells were cultured in lymphoid organoids with or without RGD binding ligands and mitomycin C-treated FDCs. VPM peptide cross-linked hydrogel organoids were stained with live/dead staining and imaged with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at day 4. To analyze the colocalization and clustering of lymphomas, 12,000 HBL-1 or OCI-Ly12 cells were encapsulated into the organoids and on day 4, gels encapsulating HBL-1 were stained with FITC conjugated anti-CD20 and cell tracker orange (CMRA) stained FDCs. Organoids containing OCI-Ly12 were stained with Calcein-AM. For each organoid, images were taken from 3 planes that covered the whole thickness of the entire hydrogel. The area of the 10 representative cell clusters were quantified from each of the 3 images using Image J.

2.5. Cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle analysis

Malignant B and T cell proliferation was quantified using Cell-Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega) by subtracting the background [27–29]. Briefly, FDCs were treated with mitomycin C for 45 min prior to encapsulation with lymphoma cells into the organoids. Organoids were functionalized with RGD or REDV ligands and HBL-1, OCI-Ly10, OCI-Ly12, SUDHL-6, and HUT78 were encapsulated at 12,000 cells per gel. In all these studies, FDCs were encapsulated at 6000 cells per organoid. To analyze long-term lymphoma proliferation, HBL-1 cells and FDCs were encapsulated into REDV peptide presenting organoids, cross-linked with either 100% VPM or the combination of 80% VPM with 20% DTT, or 50% VPM with 50% DTT. On day 6, 10, and 14, cells were harvested by enzymatic degradation of the hydrogels for 1 h with 25 U/mL collagenase solution (Worthington Biosciences). Cells were collected by filtering the cell-polymer suspension through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). For apoptosis analysis, harvested cells were stained with Annexin-V FITC and APC-anti human IgM and analyzed with a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

2.6. Drug response in 3D organoids

All drug studies were performed by allowing cells to proliferate in 3D organoids or 2D cultures for 4 days under normal growth conditions followed by addition of the therapeutics–doxorubicin (1 μM) or Histone Deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) Panobinostat (15 nM) for 24 h. After incubation with drug, cells were harvested by degrading the hydrogels with 50 U/mL collagenase for 2 h, and stained with Annexin V-FITC and lymphoma specific markers (IgM or CD2; for the exclusion of non-proliferative FDC cells), and analyzed using Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software with Tukey’s test (1-way ANOVA) or Bonferroni correction (2-way ANOVA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All studies were performed in triplicates unless otherwise noted. All values are reported as Mean ± S.E.M.

3. Results

3.1. Predominant αvβ3 integrin expression in T cell but not in B cell lymphomas

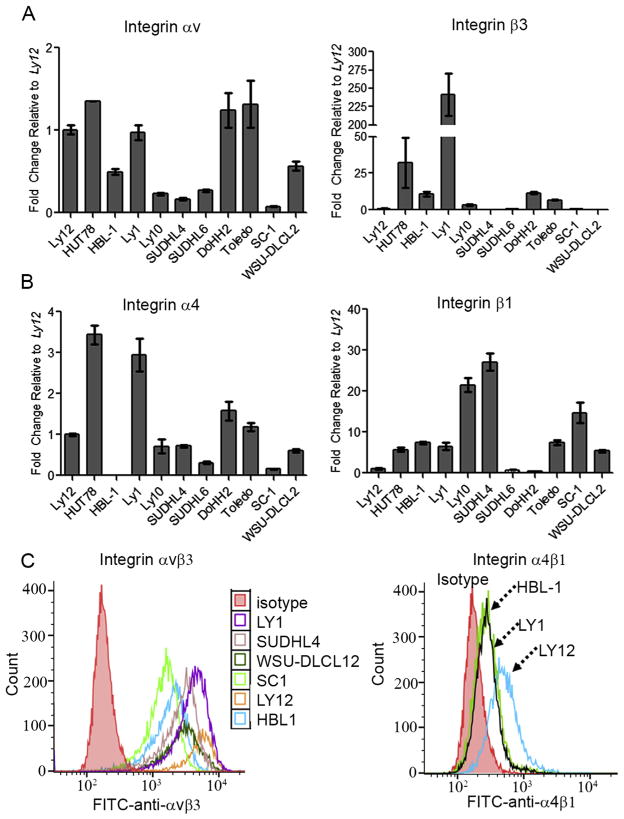

We have recently reported that αvβ3 integrin is required for T cell lymphoma survival and proliferation [12]. To determine whether αvβ3 integrin is also expressed in B cell lymphomas, we analyzed gene and protein expression across a panel of human Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cells including Activated B cell types (ABC-DLBCLs, OCI-Ly10; HBL-1), Germinal center B cell type (GCB-DLBCLs, OCI-Ly1, Toledo, SUDHL-4 and SUDHL-6), and transformed Follicular B cell lymphoma cell lines (SC-1, DoHH2 and WSU-DLCL2). We compared and contrasted expression in B cell lymphomas with known expression in T cell lymphoma cell lines HuT-78 (cutaneous T cell lymphoma, CTCL) and OCI-Ly12 (peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, PTCL-NOS) [12]. Data was normalized to OCI-Ly12 cells. Consistent with our previous findings [12], the T cell NHL cells expressed αvβ3 at the RNA and protein levels (Fig. 1A). Expression of αvβ3 in B cell lymphoma was more varied, with cell lines expressing consistently high levels (OCI-Ly1 and HBL-1, Fig. 1A). We next evaluated the mRNA levels of another integrin dimer, α4β1, with known roles in lymphoid tissues as very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) [30]. As indicated in Fig. 1B, all B and T cell lymphomas expressed similar or higher levels of β1 integrin subunits as compared to OCI-Ly12 cells. Of these cells, HuT-78 T cell lymphomas expressed the highest mRNA levels of integrin α4 subunit. Similar to αvβ3, flow cytometry results indicated an increased expression of α4β1 in B cell lymphomas (HBL-1 and OCI-Ly1) compared to the isotype controls but lower than OCI-Ly12 T cell lymphoma (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that while αvβ3 integrin is consistently overexpressed in T cell lymphomas, T-NHLs also express varying levels of α4β1. B cell lymphomas on the other hand, do not have a predictable pattern of integrin expression. These findings form our rationale for the need of a modular plug-play system where integrin ligands could be changeable based on the pattern of integrin receptor expression in a particular B or T cell lymphoma cell line.

Fig. 1.

Integrin expression in B and T NHLs. (A–B) mRNA levels of integrin αvβ3 and α4β1 by q-RT-PCR in a panel of B and T cell lymphoma lines representing the spectrum of disease (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3). (C) Flow cytometry representing the surface expression level of integrin dimer αvβ3 and α4β1 in lymphoma cell lines.

3.2. Biomaterials-based modular organoids present integrin specificities to encapsulated cells and regulate FDC clustering

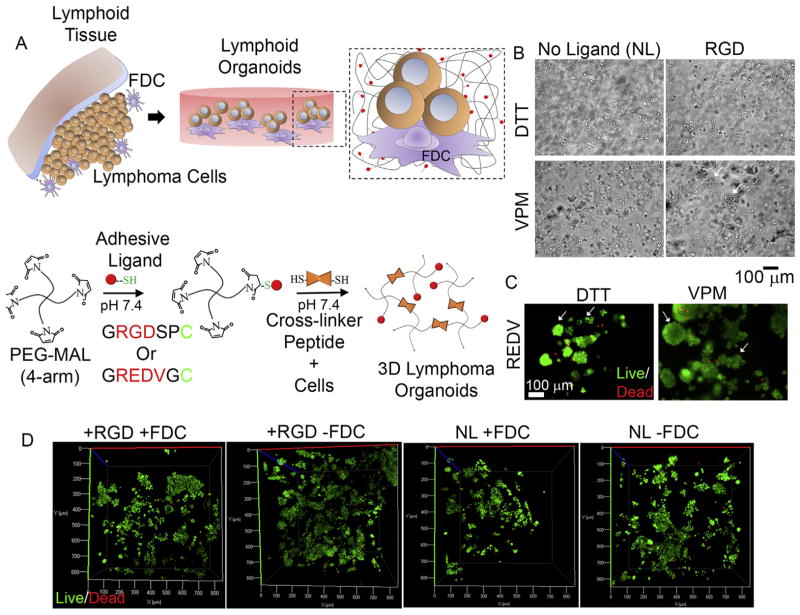

We engineered a modular organoid by using our previously reported Michael addition-chemistry based hydrogels [26] where Maleimide functionalized 4-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG-MAL) reacts with thiolated peptides to form a bio-adhesive hydrogel (Fig. 2A). We functionalized the hydrogels with 25% thiolated peptides presenting αvβ3 binding RGD ligands or α4β1 binding REDV ligands, and cross-linked the hydrogels using matrix metal-loproteinase (MMP) 9 degradable, di-thiolated peptide (NH2-GCRDVPMSMRGGDRCG-COOH). MMP-9 has been reported to almost universally expressed in patients with both T and B cell lymphomas [31–35]. A non-degradable linker (DTT) was used as a control, or to regulate the hydrogels’ degradation kinetics, in these studies. As indicated in Fig. 2B, in the presence of non-degradable DTT linker, FDCs were distributed as individual cells throughout the hydrogel organoids, independent of adhesive ligand RGD. In organoids cross-linked with MMP-9 degradable VPM peptide, the absence of RGD signaling led to single cell distribution, however, presence of RGD resulted in clustering of FDCs (white arrows). In similar organoids cross-linked with MMP-9 degradable VPM, presentation of REDV ligands instead of RGD resulted in large clusters of FDCs. In contrast, non-degradable organoids formed small clusters (Fig. 2C). We next evaluated the survival and apoptosis of malignant B cells (HBL-1) and observed near 100% survival from live/dead fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 2D). The survival efficiency was comparable to the 2D cultures.

Fig. 2.

Lymphoma-specific integrin ligand presenting modular organoids (A) Schematic represents organoid formation and underlying Michael-addition chemistry. B and T cell lymphomas, together with follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), were encapsulated within 4-arm PEG-Maleimide (PEG-MAL) hydrogels, presenting peptide ligands for integrins that were cross-linked by MMP-9 degradable peptides (VPM). (B–C) Phase contrast images of FDCs encapsulated inside hydrogel organoids presenting RGD or no ligands and cross-linked using non-degradable DTT or MMP-9 degradable VPM peptides (B) and FDC cells encapsulated within REDV hydrogels cross-linked using VPM and DTT and stained for Calcein-AM and ethidium homodimer 1 (C). White arrows represent FDC aggregates. (D) Confocal microscopy projections represent live/dead population of HBL-1 encapsulated within various hydrogels.

3.3. Lymphoma-specific microenvironmental signaling supports lymphoma clustering and proliferation

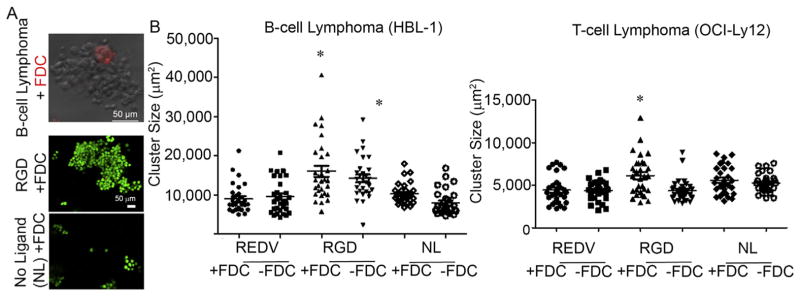

Since lymphomas grow as aggregates in patients, we examined the role of the 3D microenvironment on spatial organization in the organoids. We evaluated the effect of integrin ligands and FDCs on the clustering of lymphoma cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, the FDCs localized with clusters of lymphoma cells. The majority of the cells in the cluster were B cell lymphoma cells, as identified by the expression of the CD20 surface marker. We determined the effect of integrin ligand type on B and T cell lymphoma clustering and observed that the presence of RGD ligands, together with FDC cells, significantly increased lymphoma cell clustering for both B and T tumor types (Mean HBL-1 cluster area 16,000 ± 1400 μm2 for +RGD + FDC compared to 9000 ± 700 μm2 for +REDV + FDC, ANOVA, n = 30 clusters). Interestingly, in the absence of FDCs, RGD ligands resulted in significant clustering (comparable to +RGD + FDCs) for B cell NHLs, however, did not promote the clustering of T cell NHLs (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Figure S1).

Fig. 3.

Clustering of lymphomas in 3D lymphoid microenvironments. (A) Top Panel: Representative confocal microscopy image of the co-localization of B and T cell lymphomas and FDCs, pre-stained with cell tracker orange. Bottom Panel: B cell lymphomas were stained with FITC conjugated anti-CD20 (and with ethidium homodimer I to label dead cells) to confirm that clustering of lymphomas. (B) Quantification of the size of colonies (images from 3 planes were taken from each organoid for each condition. 10 largest colonies from each plane were pooled and analyzed). *p < 0.05, ANOVA.

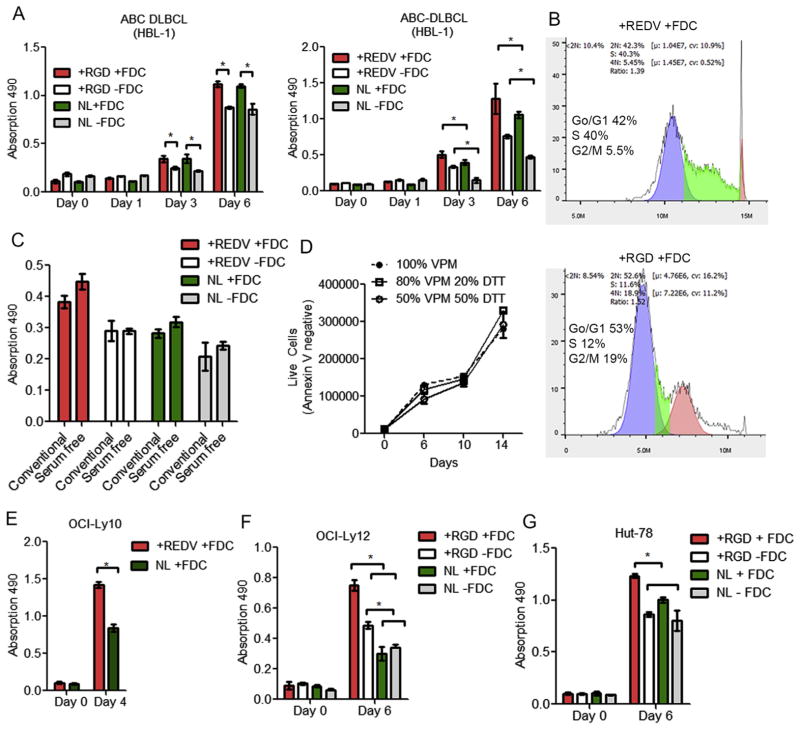

We hypothesized that hydrogel organoids with integrin specificities will signal pro-survival factors in lymphoma cells while protease degradability will facilitate matrix remodeling during cell growth. In B cell lymphomas (HBL-1), the presence of FDCs significantly increased HBL-1 proliferation, regardless of the presence of RGD ligand (Fig. 4A). However, the presence of REDV ligand significantly increased the proliferation of HBL-1 cells in FDC containing organoids. These findings emphasize the importance of integrin subtype and FDCs in lymphoma proliferation in 3D microenvironments, a concept that has been largely ignored in previous lymphoma studies. We next evaluated the effect of integrin specificities and the presence of stromal FDCs on lymphoma cell cycle and observed a marked decrease in the DNA synthesis phase (S) of the HBL-1 cells cultured in RGD functionalized organoids in the presence of FDCs (12%) compared to those in organoids with REDV ligand (~40%, Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Lymphoid-mimicking organoids regulate proliferation of B and T NHLs. Proliferation of HBL-1 cells in organoids presenting (A) REDV or RGD or no ligand (NL), with or without FDCs (HK). Proliferation was quantified with MTS assay, with FDCs pre-treated with mitomycin C (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05). (B) Cell cycle analysis of DLBCL HBL-1 cells using flow cytometry and FlowJo in-built cell cycle software. (Representative images from n = 3 independent repeats). (C) Effect of serum–free conditions on growth of B cell lymphomas (HBL-1) in organoids (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3). (D) Long term proliferation of HBL-1 in 100% VPM or 20% DTT + 80% VPM or 50% DTT + 50% VPM organoids. Live cells were quantified using flow cytometer with Annexin V staining (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3). (E) Proliferation of OCI-Ly10 cells in organoids presenting REDV or NL, with FDCs. (F–G) Proliferation of (F) HuT-78 cells and (G) OCI-Ly12 cells in organoids presenting RGD or no ligand, with or without FDCs. Proliferation was quantified using MTS assay, with FDCs pre-treated with mitomycin C (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05).

We then evaluated the role of serum conditions on cell proliferation in organoids and observed no significant difference between regular culture conditions versus the serum-free culture condition, with +REDV + FDC organoids supporting the maximum proliferation of HBL-1 cells (Fig. 4C). Since cell lines of different lymphoma subtypes could produce different levels of MMP-9, we, therefore, investigated the long term stability of organoids and proliferation of malignant B cells by mixing 20% or 50% non-degradable crosslinker (DTT) with protease degradable VPM peptide. As indicated in Fig. 4D, the organoids were stable for at least 14 days and no significant difference in proliferation was observed upon incorporation of DTT to the organoids. We next performed the proliferation analysis of another ABC-DLBCL tumor cell line (OCI-Ly10) and observed significant proliferation in the presence of REDV in 3D organoids, as compared to organoids functionalized with no ligands (Fig. 4E). Finally, we investigated the role of integrins and FDCs on malignant T cell lymphomas. As indicated in Fig. 4F and G, proliferation of two different T cell lymphomas increased according to the presence of RGD and FDCs. For the CTCL cells HuT-78, RGD presentation resulted in enhanced proliferation of cells in the presence of FDCs. Similar results were observed with the PTCL-NOS OCI-Ly12 cells.

3.4. 3D microenvironment promotes drug resistance against standard chemotherapy and new class of chemotherapy-free epigenetic drugs

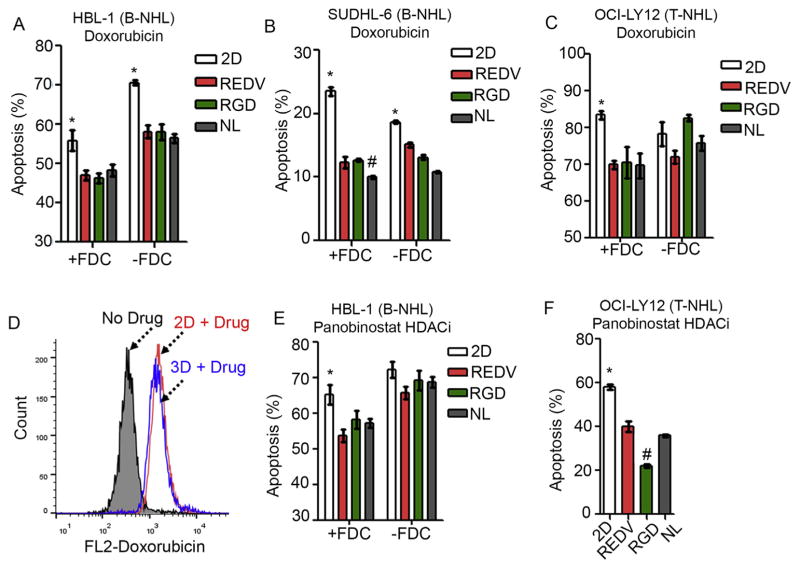

As we discussed earlier, established chemotherapeutics as well as new agents are routinely tested with suspension 2D cultures of B and T cell lymphomas, without any context to 3D microenvironment. To understand the role of the 3D microenvironment in drug efficacy, malignant B and T cells cultured in 3D organoids or in 2D cultures were exposed to 1 μM doxorubicin for 24 h. As indicated in Fig. 5A and B, B cell lymphomas were significantly resistant to doxorubicin treatment in optimized 3D organoids as compared to 2D conditions (Apoptosis for HBL-1: 47 ± 1% for +REDV + FDC versus 56 ± 2% for 2D + FDC, p < 0.05, and for SUDHL-6: 12 ± 1% for +REDV + FDC versus 23 ± 1% for 2D + FDC, p < 0.05). The presence of FDCs decreased the effect of doxorubicin in 2D and 3D conditions. A similar effect was seen with T NHL cells growing in their optimized 3D organoids (69 ± 1% apoptosis in 3D, compared to 83 ± 1% in 2D + FDC, Fig. 5C). To confirm that the observed phenomenon was due to 3D microenvironment and not drug diffusion limitations, we performed drug uptake studies in 2D versus 3D cultures and observed no difference in drug availability to the cells in organoids compared to 2D culture (mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) 1570 and 1430, respectively, Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

3D microenvironment induces drug resistance in B and T NHL against doxorubicin and histone deacetylase inhibitor Panobinostat. (A–B) Bar graphs represent % apoptosis in B cell lymphomas exposed to doxorubicin. B cell lymphomas (A) HBL-1 and (B) SUDHL-6 were cultured for 4 days in 2D or 3D organoids and exposed to 1 μM doxorubicin for 24 h. B cell lymphomas were stained with APC-IgM BCR and Annexin V-FITC for apoptosis analysis (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared to all 3D groups and #p < 0.05 compared to all other 3D and 2D groups). (C) T-cell lymphoma OCI-Ly12 was cultured for 4 days in 2D or 3D organoids and exposed to 1 μM doxorubicin for 24 h. T cell lymphomas were stained with APC-CD2 -and Annexin V-FITC for apoptosis analysis (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared to all 3D groups). (D) Histogram representing doxorubicin drug uptake by B cell lymphoma cells. Doxorubicin was added to B cell lymphomas in 2D or 3D culture and after 2 h, cells were analyzed using flow cytometer. (E–F) Bar graphs represent % apoptosis in B cell lymphomas exposed to histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) Panobinostat. B cell lymphoma HBL-1 (E) and T cell lymphoma OCI-Ly12 (F) were cultured for 4 days in 2D cultures or 3D organoids and exposed to 15 nM Panobinostat for 24 h. OCI-Ly12 data represents co-culture with FDCs. T cell lymphomas were stained with APC-CD2 and Annexin V-FITC for apoptosis analysis (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared to all 3D groups and #p < 0.05 compared to all other 3D and 2D groups).

We next evaluated the effect of a new histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) agent, Panobinostat, that is being tested in patients with T and B cell lymphomas. We exposed HBL-1 and OCI-Ly12 to 15 nM of Panobinostat and observed significantly lower levels of drug-induced apoptosis in HBL-1 3D organoids (54 ± 2% (+REDV + FDC) vs. 66 ± 3% (2D + FDC), p < 0.05) and Ly12 3D organoids (22 ± 1% +RGD + FDC vs. 58 ± 1% 2D +FDC, p < 0.05, Fig. 5E and F). These findings clearly support the hypothesis that the 3D microenvironment plays a critical role in drug resistance and emphasizes the need for 3D organoids for more accurate anti-lymphoma drug testing.

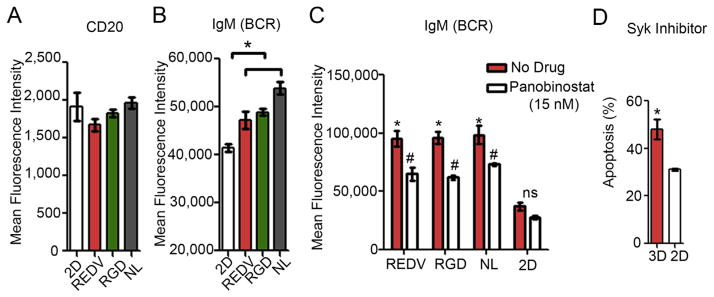

3.5. 3D microenvironment upregulates B cell receptor and interferes with cellular apoptosis against anti-neoplastic drugs in B cell lymphomas

We next examined the effect of the 3D microenvironment on conventional surface markers expressed on malignant B cells. As indicated in Fig. 6A and Supplementary Figure S2, CD20 and CD19 expression levels remained largely unchanged in 3D organoids with integrin ligands and FDCs, as compared to 2D culture conditions with FDCs. In contrast, B cell receptor (BCR) IgM was significantly upregulated in 3D microenvironment with FDCs irrespective of ligands, as compared to the 2D co-culture with FDCs (MFI 54,000 ± 1300 with NL + FDC compared to 41,000 ± 800 with 2D + FDC; Fig. 6B). Previous studies have shown that the expression of IgM is a hallmark of several malignant B cells, which contain it as a part of the BCR [36,37]. We further investigated the effect of Panobinostat treatment on IgM expression in 3D organoids. As indicated in Fig. 6C, when exposed to 15 nM Panobinostat, the IgM expression level reduced overall in the 3D microenvironment, however, remained significantly higher than 2D co-culture treated with identical doses of the drug (MFI 95,500 ± 6600 with +REDV + FDC before the Panobinostat treatment versus 37,300 ± 3,600, after treatment). It is known that BCR signaling in ABC DLBCL resembles a chronic active rather than the tonic (continuous) BCR signaling and these NHLs are susceptible to death or anti-proliferative effect by knockdown of any BCR component or proximal BCR signaling effectors, including SYK – a tyrosine kinase in the upstream BCR pathway (see molecular details in Refs. [38–40]). We therefore used a Syk inhibitor (R406) previously reported with DLBCL [41,42], and observed that ABC DLBCL HBL-1 cells had significantly higher apoptosis in the 3D REDV + FDC group as compared to 2D + FDC group (p < 0.05, Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Effect of 3D organoids on B NHL markers and B cell receptor. (A–B) Bar graphs represent flow cytometry analysis of (A) CD20 and (B) IgM surface markers in DLBCL line HBL-1 cells cultured in 2D condition or 3D organoids (all with FDCs). Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05, ANOVA (C) Bar graph represents mean fluorescence intensity of IgM BCR expression in presence or absence of HDACi Panobinostat (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05, ANOVA). (D) Bar graph represents % apoptosis in DLBCL line HBL-1 exposed to 4 μM Syk inhibitor, R406, for 24 h after 4 days of culture in organoids or 2D in the presence of FDCs (Mean ± S.E.M, n = 3, *p < 0.05, t-test).

4. Discussion

Integrins are heterodimeric (αβ) cell surface receptors that mediate adhesion to the ECM components, such as fibronectin (FN) and laminin, and immunoglobulin superfamily molecules [43–48]. Integrins are central to cell invasion and migration, not only for the physically tethering of spread and suspension cells to the matrix, but also for communicating molecular signals that regulate these processes [49]. Altered integrin expression or signaling is frequently associated with lymphoid tumor cell invasion and growth [50]. We have recently established the critical role of integrin αvβ3 in the survival of a wide range of T cell lymphomas, especially cutaneous T cell lymphomas, but not healthy circulating T cells [12]. We demonstrated that pharmacologic inhibition of integrin αvβ3 with systemically delivered Cilengitide, a peptide drug that binds to avb3, reduced the proliferation of human patient-derived T cell lymphoma tumors in xenograft models in mice. In the current study, we observed differential expression of αvβ3 and α4β1 in B and T cell lymphomas across a wide range of tumor subtypes. To allow for the observed variability in the integrin expression profile of B and T cell lymphoma lines, we engineered modular lymphoid-mimicking 3D microenvironments using our recently reported protease-degradable PEG-MAL hydrogels [26] presenting defined densities of adhesive ligands with different integrin specificities (αvβ3 vs α4β1) to the lymphoma cells along with FDCs. We anticipate such modular hydrogels to be suitable in accordance to the patient lymphoma type and pattern of integrin expression. Although Michael-addition click-chemistry based hydrogels [27,28,51–54] have been developed with other cellular models such as pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDEC) [55], pancreatic islet engraftment and function in type 1 diabetes [56,57], and cervical cancer by us [58], to our knowledge, biomaterials-based 3D ex vivo cultures of lymphomas have not been reported. The closest available 3D culture is a multicellular aggregate of lymphoma that does not account for a 3D extracellular matrix [18].

Our findings suggest that B and T cell tumors have different pro-survival signaling requirements. In B cell lymphomas (HBL-1), the presence of REDV ligand significantly increased the proliferation of HBL-1 cells in FDC containing organoids. On the contrary, proliferation of T cell lymphomas was dependent on the presence of RGD and FDCs. Interestingly, for OCI-Ly12 T cell lymphomas, +RGD-FDC conditions also induced significantly higher proliferation than no ligand (NL)+FDC and blank organoids, emphasizing the role of RGD and αvβ3 signaling in T NHLs, similar to what we have previously reported [12]. These findings emphasize the importance of integrin subtype and FDCs in lymphoma proliferation in 3D microenvironments. Previous studies have indicated that integrin mediated signaling is crucial for progression through the G1/S checkpoint of the cell cycle [59]. In mammalian cells, integrins indirectly recruit focal adhesion proteins such as talin and paxillin, as well as focal adhesion kinase (Fak), which control downstream signaling, levels of cyclins, and the genes essential for proliferation, such as c-Jun and E2F [60]. To further characterize the role of integrin-specific ligand presentation in organoids, we measured cell-cycle progression in the HBL-1 B cell lymphomas. We observed a marked decrease in the S phase of the cell cycle of the HBL-1 cells when cultured in RGD functionalized organoids with FDCs, compared to those in organoids with REDV ligand. These findings suggest an enhanced DNA synthesis and proliferation when exposed to REDV ligands.

We observed enhanced clustering of both B and T lymphomas in RGD presenting organoids, which may have implications in closer resemblance to lymphomas that grow as dense aggregates in patients. These findings are further supported by a recent study using multicellular aggregates of lymphoma cells, which showed that clustering strongly affects the proliferation of lymphomas and their signaling pathway [18]. However, the mechanism by which NHLs cultured in organoids exclusively cluster in the presence of RGD (but not REDV) and its implication in proliferation or drug resistance remains to be identified. In contrast to lymphoma cells, FDCs formed larger clusters in REDV presenting organoids than in RGD presenting organoids. These differences were only observed when the organoids were formed with MMP-degradable cross-linker peptides.

One of our key findings is the 3D microenvironment mediated drug resistance of lymphoma cells with conventional chemotherapy and epigenetic drugs such as HDACi. HDACi are a new class of drugs that have shown promise in early-phase clinical trials for the treatment of hematological malignancies. For example, in a phase II B study [61], 24% of refractory cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) patients who had originally failed conventional therapies had a complete or partial response to vorinostat, an FDA approved HDACi. Another drug of interest is Panobinostat that has been tested in hematological malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [62] and multiple myeloma [63,64]. Panobinostat has recently entered into phase II clinical trial with other hematological malignancies. However, not much is known about the drug and its mechanism of action in B cell lymphomas, especially in the context of the microenvironment. Our study shows that NHLs in organoids acquire resistance to both doxorubicin and Panobinostat. In particular, OCI-LY12 Tcell lymphomas demonstrated maximum resistance to Panobinostat in organoids presenting RGD ligands as compared to REDV and no ligand hydrogels. The observed apoptosis and drug resistance were specific to microenvironment signaling and not because of drug diffusion-associated limitations. The diffusion of drug into the hydrogels reached equilibrium within 2 h. Finally, our results demonstrated the role of the 3D microenvironment on BCR signaling in malignant B cells. BCR is an essential signal transduction pathway for the survival and proliferation of mature B lymphocytes [30,65] and likely plays a major role in the context of prognosis and positive selection of the precursor tumor cell. In particular, IgM BCR is vital for the survival of ABC DLBCL through the NF-κB pathway and other possible mechanisms and the knockdown of IgM results in apoptosis of ABC DLBCL [38]. In our studies, we observed the 3D microenvironment to upregulate IgM BCR expression level, which indicate enhanced survival and possibly explains the enhanced proliferation observed with B cell lymphomas. We predict that activation of BCR is likely supporting the survival of B NHLs in 3D niches over 2D cultures by means of both up-regulating BCR and cross-talk with integrins. This hypothesis is supported by our findings with Syk inhibition that caused significantly higher apoptosis in the 3D group as compared to the 2D groups.

Taken together, these results emphasize the role of biomaterials-based 3D tissues and the importance of integrin mediated signaling in malignant B and T cell tumors, as well as the role of FDCs in lymphoma proliferation. In the past, these factors have been largely ignored in drug evaluation or mechanistic studies of B and T cell lymphomas, ex vivo. Therefore, investigation of chemotherapeutics and upcoming new classes of therapeutic agents that target epigenome, matrix, or angiogenic pathways should consider the potential confounding interactions between the lymphoid tumor microenvironment and lymphoid tumors at cell–cell and cell-integrin levels. Currently, it is not possible to accurately and efficiently predict how epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming drugs should be administered to patients, the time frame, and what sub-set of patients will most likely benefit from these agents. Our functionalized 3D organoid system mimics a neoplasm-like heterogeneous microenvironment that could, in the long term, support the growth of primary human lymphomas that, integrated to the molecular characterization of patients’ lymphomas, will pave the path to better predict the response of epigenetic and metabolic drugs, which are challenging to study and potentially very effective in treating B and T cell tumors. Together, these new findings may enhance the efficacy of existing pharmaceutical regimens in the treatment of B and T cell lymphomas as well as other hematological malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (1R21CA185236-01), the Cornell University and Weill Cornell Medical College Seed Grant Program, and Cornell University’s Engineering Learning Initiative Grant. The authors thank Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center (and NIH S10RR025502) for the use of microscopy resources. The authors thank Giorgio Inghirami at Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University for providing insights into lymphoma studies.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.09.007.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Y.F.T. conducted all experiments, collected data and performed data analysis. H.A, S.N.Y, and L.R-G performed q-RT-PCR. R.S.S and Y.F.T. conducted clustering experiments and analysis. A.S developed the concept and together with L.C and A.M.M contributed to the planning and design of the project. Y.F.T. wrote the manuscript with A.S and L.C. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- 1.Cerchietti L, et al. Inhibition of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) activity provides a therapeutic approach for CLTC-ALK-positive human diffuse large B cell lymphomas (Translated from eng) PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018436. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerchietti LC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of BCL6 kills DLBCL cells in vitro and in vivo (Translated from eng) Cancer Cell. 2010;17(4):400–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.050. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerchietti LC, et al. BCL6 repression of EP300 in human diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells provides a basis for rational combinatorial therapy (Translated from Eng) J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4569–4582. doi: 10.1172/JCI42869. (in Eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerchietti LC, et al. A purine scaffold Hsp90 inhibitor destabilizes BCL-6 and has specific antitumor activity in BCL-6-dependent B cell lymphomas (Translated from eng) Nat Med. 2009;15(12):1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm.2059. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerchietti LC, et al. Sequential transcription factor targeting for diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (Translated from eng) Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3361–3369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5817. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polo JM, et al. Specific peptide interference reveals BCL6 transcriptional and oncogenic mechanisms in B-cell lymphoma cells (Translated from eng) Nat Med. 2004;10(12):1329–1335. doi: 10.1038/nm1134. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polo JM, et al. Transcriptional signature with differential expression of BCL6 target genes accurately identifies BCL6-dependent diffuse large B cell lymphomas (Translated from eng) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(9):3207–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611399104. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inghirami G, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of T-BAM (CD40 ligand)+ T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Translated from eng) Blood. 1994;84(3):866–872. (in eng) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scandurra M, et al. Genomic lesions associated with a different clinical outcome in diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP-21 (Translated from eng) Br J Haematol. 2010;151(3):221–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08326.x. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Valdez H, et al. Human germinal center B cells express the apoptosis-inducing genes Fas, c-myc, P53, and Bax but not the survival gene bcl-2 (Translated from eng) J Exp Med. 1996;183(3):971–977. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.971. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott DW, Gascoyne RD. The tumour microenvironment in B cell lymphomas (Translated from eng) Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(8):517–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc3774. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cayrol F, et al. Integrin alphavbeta3 acting as membrane receptor for thyroid hormones mediates angiogenesis in malignant T cells (Translated from eng) Blood. 2015;125(5):841–851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587337. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damiano JS, Dalton WS. Integrin-mediated drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;38(1–2):71–81. doi: 10.3109/10428190009060320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naci D, et al. alpha2beta1 integrin promotes chemoresistance against doxorubicin in cancer cells through extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(21):17065–17076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.349365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz G, et al. Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(22):2313–2323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng C. Microenvironmental protection in diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(22):2379–2381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0808409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh RR, et al. ABCG2 is a direct transcriptional target of hedgehog signaling and involved in stroma-induced drug tolerance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncogene. 2011;30(49):4874–4886. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravelle P, et al. Cell growth in aggregates determines gene expression, proliferation, survival, chemoresistance, and sensitivity to immune effectors in follicular lymphoma (Translated from eng) Am J pathol. 2014;184(1):282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.018. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caicedo-Carvajal CE, Liu Q, Remache Y, Goy A, Suh KS. Cancer tissue engineering: a novel 3D polystyrene scaffold for in vitro isolation and amplification of lymphoma cancer cells from heterogeneous cell mixtures (Translated from eng) J Tissue Eng. 2011:362326. doi: 10.4061/2011/362326. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver VM, et al. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three-dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies (Translated from eng) J Cell Biol. 1997;137(1):231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver VM, et al. beta4 integrin-dependent formation of polarized three-dimensional architecture confers resistance to apoptosis in normal and malignant mammary epithelium (Translated from eng) Cancer Cell. 2002;2(3):205–216. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00125-3. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee GY, Kenny PA, Lee EH, Bissell MJ. Three-dimensional culture models of normal and malignant breast epithelial cells (Translated from eng) Nat Methods. 2007;4(4):359–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1015. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller BE, Miller FR, Heppner GH. Factors affecting growth and drug sensitivity of mouse mammary tumor lines in collagen gel cultures (Translated from eng) Cancer Res. 1985;45(9):4200–4205. (in eng) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua H, Li M, Luo T, Yin Y, Jiang Y. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumorigenesis: an evolving paradigm (Translated from eng) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(23):3853–3868. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0763-x. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erler JT, Weaver VM. Three-dimensional context regulation of metastasis (Translated from eng) Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(1):35–49. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9209-8. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee TT, et al. Light-triggered in vivo activation of adhesive peptides regulates cell adhesion, inflammation and vascularization of biomaterials (Translated from eng) Nat Mater. 2015;14(3):352–360. doi: 10.1038/nmat4157. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A, et al. An injectable synthetic immune-priming center mediates efficient T-cell class switching and T-helper 1 response against B cell lymphoma (Translated from eng) J Control release official J Control Release Soc. 2011;155(2):184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.008. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh A, Suri S, Roy K. In-situ crosslinking hydrogels for combinatorial delivery of chemokines and siRNA-DNA carrying microparticles to dendritic cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5187–5200. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh A, et al. Efficient modulation of T-cell response by dual-mode, single-carrier delivery of cytokine-targeted siRNA and DNA vaccine to antigen-presenting cells (Translated from eng) Mol Ther. 2008;16(12):2011–2021. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.206. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arana E, Harwood NE, Batista FD. Regulation of integrin activation through the B-cell receptor (Translated from eng) J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 14):2279–2286. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017905. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouchard F, Belanger SD, Biron-Pain K, St-Pierre Y. EGR-1 activation by EGF inhibits MMP-9 expression and lymphoma growth. Blood. 2010;116(5):759–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennanen H, Kuittinen O, Soini Y, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T. Prognostic significance of p53 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in follicular lymphoma (Translated from eng) Eur J Haematol. 2008;81(4):289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01113.x. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozkurt C, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP-1) in tissues with a diagnosis of childhood lymphoma (Translated from eng) Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;25(7):621–629. doi: 10.1080/08880010802313657. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakata K, et al. The enhanced expression of the matrix metalloproteinase 9 in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma (Translated from eng) BMC Cancer. 2007;7:229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-229. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakata K, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 is a prognostic factor in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Translated from eng) Cancer. 2004;100(2):356–365. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11905. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito Y, et al. B-cell-activating factor inhibits CD20-mediated and B-cell receptor-mediated apoptosis in human B cells (Translated from eng) Immunology. 2008;125(4):570–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02872.x. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franke A, Niederfellner GJ, Klein C, Burtscher H. Antibodies against CD20 or B-cell receptor induce similar transcription patterns in human lymphoma cell lines (Translated from eng) PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016596. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis RE, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Translated from eng) Nature. 2010;463(7277):88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young RM, Staudt LM. Targeting pathological B cell receptor signalling in lymphoid malignancies (Translated from eng) Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):229–243. doi: 10.1038/nrd3937. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Wilson WH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma-treatment approaches in the molecular era (Translated from eng) Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(1):12–23. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.197. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S, et al. SYK inhibition and response prediction in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Translated from eng) Blood. 2011;118(24):6342–6352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-333773. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L, et al. SYK-dependent tonic B-cell receptor signaling is a rational treatment target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Translated from eng) Blood. 2008;111(4):2230–2237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100115. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanchanawong P, et al. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions (Translated from eng) Nature. 2010;468(7323):580–584. doi: 10.1038/nature09621. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kinashi T. Intracellular signalling controlling integrin activation in lymphocytes (Translated from eng) Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(7):546–559. doi: 10.1038/nri1646. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tadokoro S, et al. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation (Translated from eng) Science. 2003;302(5642):103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Rodda LB, Bannard O, Cyster JG. Integrin-mediated interactions between B cells and follicular dendritic cells influence germinal center B cell fitness (Translated from eng) J Immunol. 2014;192(10):4601–4609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400090. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coyer SR, et al. Nanopatterning reveals an ECM area threshold for focal adhesion assembly and force transmission that is regulated by integrin activation and cytoskeleton tension (Translated from English) J Cell Sci. 2012;125(21):5110–5123. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108035. (in English) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration (Translated from eng) Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(2):91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vacca A, et al. alpha(v)beta(3) integrin engagement modulates cell adhesion, proliferation, and protease secretion in human lymphoid tumor cells. Exp Hematol. 2001;29(8):993–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller JS, et al. Bioactive hydrogels made from step-growth derived PEG-peptide macromers (Translated from eng) Biomaterials. 2010;31(13):3736–3743. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.058. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hiemstra C, Aa LJ, Zhong Z, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J. Rapidly in situ-forming degradable hydrogels from dextran thiols through Michael addition (Translated from eng) Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(5):1548–1556. doi: 10.1021/bm061191m. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Thiolene click chemistry (Translated from eng) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(9):1540–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoyle CE, Lowe AB, Bowman CN. Thiol-click chemistry: a multifaceted toolbox for small molecule and polymer synthesis (Translated from eng) Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39(4):1355–1387. doi: 10.1039/b901979k. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raza A, Ki CS, Lin CC. The influence of matrix properties on growth and morphogenesis of human pancreatic ductal epithelial cells in 3D (Translated from eng) Biomaterials. 2013;34(21):5117–5127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.086. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phelps EA, et al. Maleimide cross-linked bioactive PEG hydrogel exhibits improved reaction kinetics and cross-linking for cell encapsulation and in situ delivery (Translated from eng) Adv Mater. 2012;24(1):64–70. 62. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103574. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phelps EA, Headen DM, Taylor WR, Thule PM, Garcia AJ. Vasculogenic bio-synthetic hydrogel for enhancement of pancreatic islet engraftment and function in type 1 diabetes (Translated from eng) Biomaterials. 2013;34(19):4602–4611. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.012. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel RG, et al. Microscale Bioadhesive Hydrogel Arrays for Cell Engineering Applications (Translated from eng) Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7(3):394–408. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0353-8. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreno-Layseca P, Streuli CH. Signalling pathways linking integrins with cell cycle progression (Translated from eng) Matrix Biol. 2014;34:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.011. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker JL, Assoian RK. Integrin-dependent signal transduction regulating cyclin D1 expression and G1 phase cell cycle progression (Translated from eng) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24(3):383–393. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5130-7. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duvic M, Vu J. Update on the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL): Focus on vorinostat (Translated from eng) Biol Targets & Ther. 2007;1(4):377–392. (in eng) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandawat A, et al. Pan-histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat depletes CXCR4 levels and signaling and exerts synergistic antimyeloid activity in combination with CXCR4 antagonists (Translated from eng) Blood. 2010;116(24):5306–5315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284414. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richardson PG, et al. PANORAMA 2: panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and bortezomib-refractory myeloma (Translated from eng) Blood. 2013;122(14):2331–2337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-481325. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nooka AK, Kastritis E, Dimopoulos MA, Lonial S. Treatment options for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (Translated from eng) Blood. 2015;125(20):3085–3099. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-568923. (in eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spaargaren M, et al. The B cell antigen receptor controls integrin activity through Btk and PLCgamma2 (Translated from eng) J Exp Med. 2003;198(10):1539–1550. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011866. (in eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.