Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) serves as an innate resistance niche for chemotherapy assault and a physiological barrier against therapeutic nanoparticles (NP) penetration. Previous studies have indicated that therapeutic NP can distribute to and deplete tumor associated fibroblasts (TAF) for improved therapeutic outcome. However, resistance develops after repeated chemotherapeutic NP exposure. In this study, we explored NP-delivered cisplatin induced resistance in the TME by investigating the effects of NP damaged TAF on neighboring naïve cells and comparing the stroma structure of single and multiple dose NP treatments. Our study suggested that although off-targeted NP damaged TAF initially inhibited tumor growth, chronic exposure of TAF to cisplatin NP led to elevated secretion of Wnt16 in a paracrine manner that supported tumor cell resistance and stroma reconstruction. Our study demonstrates that knockdown of Wnt16 in the damaged TAF could be a promising combinatory strategy to improve efficacy of NP delivered cisplatin in a stroma-rich bladder cancer model.

Keywords: nanoparticle, Wnt16, tumor microenvironment, cisplatin, tumor associated fibroblast

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is considered the gold standard in the treatment of muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Despite the encouraging initial responses to cisplatin induced DNA damage, acquired resistance develops gradually after multiple cycles, contributing to the ultimate failure of the treatment. Efforts that modulate cisplatin sensitivity mainly focused on reversing the tumor cell autonomous resistance mechanism through co-delivery with another regimen that inhibits DNA repair enzymes, cisplatin export and others.1–4 However, inconsistency between the ex vivo prediction of combinatory drug sensitivity and the in vivo therapeutic outcome suggests that stroma cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) also play a key role in cisplatin mediated resistance.5 Stroma cells in the TME, including tumor associated macrophages (TAM), tumor associated fibroblasts (TAF) and endothelial cells, build a physical barrier by crosslinking with the extracellular matrix, modulating pericyte coverage of vascular fenestration and maintaining a high interstitial pressure to inhibit therapeutic molecules and NP penetration.6, 7 They can also mediate tumor cell-resistance in a paracrine manner by secreting cytokines and growth factors.8–13 Yet, the innate resistance from the TME still fails to explain the discrepancy between early stage treatment sensitivity and late stage therapeutic failure. This indicates that acquired resistance in the stroma cells in response to DNA damage may occur gradually during repeated treatments.

Cisplatin selectively binds with DNA by crosslinking the DNA double strands and inducing damage.14, 15 Recent research indicates that DNA damage can lead to cell apoptosis and senescence.16, 17 The damaged cells not only produce extracellular signals to reinforce the senescent arrest and promote apoptosis by autocrine or paracrine mechanisms16, 18, but also secrete pro-survival factors to promote the survival and growth of neighboring cells.19–21 Tumors and benign stroma cells, especially TAF, have been reported to respond differently to DNA damage by secreting different factors.9 This plays an important role in acquired resistance.9, 22 Wnt16, a member of the WNT family, belongs to the aforementioned secretion factors that have been recently reported and is overexpressed in TAF, rather than the tumor cells, upon DNA damage.9 Overexpression of Wnt16 in TAF is found in prostate, breast and ovarian cancers. Mutation of the Wnt pathway is closely related to carcinogenesis, stemness and angiogenesis in various cancers and disease models.23–25 Wnt16 plays a potentially significant role in regulating the crosstalk between neighboring cells during DNA damage.

Different from small molecules, nanoparticles (NP) have been designed to improve drug pharmacokinetics, facilitate their accumulation and reduce off-target adverse effects in the treatment of bladder cancer. In previous work we developed a lipid-coated, platinum-filled NP system, known as LPC, for the delivery of cisplatin (cisplatin NP).26 This cisplatin NP, with cisplatin as both the material and the drug, was characterized with an 80 wt% loading efficiency and was approximately 30 nm in diameter (Supplementary Fig. S1).27 Polyethylene glycol was conjugated onto the surface of NP for prolonged systemic circulation.28 Anisamide, a ligand for the sigma receptor, which is overexpressed on the surface of cancerous epithelial cells, was coated on the NP to enhance receptor mediated endocytosis. Cisplatin NP have been proposed for the treatment of aggressive bladder cancer and have shown a significant antitumor effect compared to free cisplatin.29 Although the NP was designed to specifically target tumor cells, off-target distribution of NP in the TAF has also been reported. 29, 30 Therefore, we hypothesized that the distribution of cisplatin NP to TAF could lead to their damage and subsequently elevate secretion of Wnt16. We also hypothesize that downregulation of Wnt16 in TAF could inhibit cisplatin NP mediated resistance and enhance the therapeutic anti-tumor efficacy.

Several studies have demonstrated functional blocking of Wnt-canonical β-catenin pathway using monoclonal antibodies or small molecule inhibitors.31 However, undesired off-target effects have led to safety concerns in this approach. RNA interference provides an alternative way to maintain specificity while also improving safety. Liposome-protamine-hyaluronic acid NP (LPH-NP) was used to encapsulate siRNA and was shown to be an effective delivery tool in various tumor models.32 Therefore, we propose a combination therapy of cisplatin NP and LPH-NP delivered siRNA against Wnt16 (siWnt NP) (Supplementary Fig. S1). This is the first time that siRNA against Wnt16 and cisplatin has been proposed as a combinatory strategy to improve therapeutic outcome.

In the current study, a stroma rich bladder cancer model (SRBC) was established by co-inoculating human basal type bladder tumor UMUC3 with mouse NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. This model resembles bladder tumor patient samples in the components and in the morphology of the TME.29 In the SRBC model, we investigated the off-target effect of cisplatin NP on TAF damage, the Wnt16 secretion level and antitumor efficacy. We also studied the role of cytokines, such as Wnt16 in the regulation of crosstalk between tumor cells and the TME. We conclude that targeting tumor-stroma regulatory cytokines in the TME along with NP-delivered chemotherapy could potentially overcome intratumoral off-target effects and improve treatment responses.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Materials

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(methoxy(polyethyleneglycol)-2000) ammonium salt (DSPE-PEG2000), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane chloride salt (DOTAP), dioleoyl phosphatidic acid (DOPA) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol, hyaluronic acid (HA), protamine sulfate (fraction ×from salmon), hexanol, triton-100, cyclohexane were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Cisplatin was purchased from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). All the other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise mentioned. DSPE-PEG-AA was synthesized based on the previous established protocols 33. The mouse Wnt16 siRNA with sequence 5’-CCAACUACUGCGUGGAGAA-3’ and the control siRNA with sequence 5’-AATCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3’ were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

The human bladder transitional cell line (UMUC3) was provided by Dr. William Kim and the mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line (NIH 3T3) was purchased from UNC Tissue Culture Facility. These two cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% feta bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis MO) or 10% bovine calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), penicillin (100 U/mL) (Invitrogen) and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (Invitrogen), respectively in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from UNC Tissue Culture Facility and cultured in HuMEC basal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and HuMEC Supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Primary antibodies used for western-blot analysis and immunostaining included rabbit anti- fibronectin, anti-alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), anti-fibroblast activation protein alpha (FAPα), GAPDH, anti-E cadherin and anti-N cadherin polyclonal antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit anti-beta catenin monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rat anti-CD31 polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and mouse monoclonal poly(ADP-ribose) antibody (PARP, Santa Cruz biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit polyclonal anti-Wnt16 antibodies (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Inc.). Secondary antibodies used for western-blot analysis and immunohistochemistry staining (IHC) included bovine anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Sigma). And secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence staining consists of FITC, Alexa Fluor ®555 and Alexa Fluor ®647 conjugated anti-rabbit and rat antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Female athymic Balb/C nude mice of 6–8 weeks old were provided by the University of North Carolina animal facility. Animals were raised in the Center for Experimental Animals (an AAALAC accredited experimental animal facility) at the University of North Carolina. All animal handling procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1 Preparation of Cisplatin NP

Cisplatin NP were formulated as previously described.26, 27, 34 Briefly, 300 µL of 200 mM cis-[Pt(NH3)2(H2O)2](NO3)2 and 300 µL of 800 mM KCl aqueous solution were separately dispersed in a mixed oil solution cyclohexane/ triton-X100/hexanol (75:15:10, V:V:V) and cyclohexane/Igepal CO-520 (71:29, V:V) to form a well-dispersed reversed micro-emulsion. Then, 500 µL of DOPA (20 mM) was added to the cisplatin precursor emulsion and the mixture were stirred for 20 min. Afterwards, the two emulsions were mixed and reacted for another 20 min. Forty mL of ethanol was then added to break the micro-emulsion and particles were collected by centrifuge at 10,000g for at least 15 min. The pellets were washed with ethanol twice to completely remove the surfactants and cyclohexane, and then re-dispersed in 2.0 mL of chloroform for storage. Finally, the preparation of cisplatin NP consisted of mixing 1 mL of cisplatin nanocores with 200 µL of 20 mM DOTAP/Cholesterol (1:1), with 20 µL of 20 mM DSPE-PEG-2000 or 20 µL of 20 mM DSPE-PEG-2000/DSPE-PEG-AA (4:1).33 After evaporating the chloroform, the residual lipid was dispersed in 100 µL of 5% glucose. The particle size of cisplatin NP was confirmed using a Malvern ZetaSizer Nano series (Westborough, MA). TEM images of LPC NP were acquired using a JEOL 100CX II TEM (JEOL, Japan). Cisplatin NP were negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate.

2.2 Preparation of siWnt NP

siWnt NP were prepared through a stepwise self-assembly process based on a previously well-established protocol.32 Briefly, cholesterol and DOTAP (1:1, mol/mol) were dissolved in chloroform and solvent was removed by rotary evaporator. The lipid film was then hydrated with distilled water to make the final concentration of 10 mmol/L cholesterol and DOTAP, respectively. Then, the liposomes were sequentially extruded through 400 nm, 200 nm, 100 nm, and 50 nm polycarbonate membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to form 70–100 nm unilamellar liposomes. The siWnt NP polyplex cores were formulated by mixing 140 µL of 36 µg protamine in 5% glucose with equal volume 24 µg siRNA and 24 µg HA in 5% glucose. The mixture solution was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and then 60 µL cholesterol/ DOTAP liposomes (10 mmol/L each) was added. Post insertion of 15% DSPE-PEG and DSPE-PEG-AA were further performed at 50 °C for 15 min. The size and surface charge of the NP were determined by Malvern ZetaSizer Nano series (Westborough, MA). TEM images were acquired using a JEOL 100 CX II TEM (JEOL, Japan). Particles were negatively stained with uranyl acetate.

2.3 Cell Treatments with Cisplatin for Induction of Wnt16

NIH3T3 fibroblasts were grown until 80% confluent in a six well plate and activated with 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Two h later, free cisplatin at concentration of 5 µM, 10 µM, 15 µM and 25 µM was added to the activated NIH3T3 and treated for another 3h before replacing into fresh full DMEM medium and continue incubating for pre-determined time. After treatment, the cells were rinsed 3× with PBS and proceeded to Western-blot assay for the analysis of Wnt16 protein level in the cells.

2.4 Western Blot Analysis

SRBC tumor samples, UMUC3 cells or NIH3T3 cells were lysed with a Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC). Protein concentration in the tumor or cell lysate was determined using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen). After dissolved, diluted, reduced and separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (Invitrogen), the proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Then the target proteins were probed with primary antibodies (1:500 dilution), followed by the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:4,000) respectively, and detected using the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The relative protein expression level was quantified with Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) using GAPDH as a loading control.

2.5 In vitro Transfection

2×105 UMUC3 cells or NIH3T3 cells were seeded into six-well plates per well. NIH3T3 cells were activated with 10 ng/mL TGFβ2h prior to NP treatment. Then LPH NP loaded with siRNA against mouse Wnt16 (siWnt NP) or control siRNA (siCont NP) were added to each well in the presence of OptiMEM medium with final concentration of 250 nmol/L. Four h after transfection, medium was washed and cells were treated for 3h with 10 µM cisplatin to boost the expression of Wnt16. The medium was then replaced with full medium and the cells were continued to be incubated overnight. The Wnt16 protein expression levels of samples after transfection were determined by western-blot analysis with GAPDH as loading control.

2.6 β-catenin Nucleus Translocation Assay

β-catenin assay was carried out to determine the canonical Wnt pathway activation in the neighboring UMUC3 cells by Wnt16 secreted from damaged fibroblast.35 A non-contact co-culture system was first established, with the upper chamber seeded with activated NIH3T3 subjected to siCont NP, siWnt NP followed by cisplatin NP treatment according to the procedure described above.36 Co-culture was initiated when putting the NIH3T3 inserts into a 24 well plate with UMUC3 seeded on a coverslip (Fishier Scientific). At indicated time points, coverslips were taken out, fixed, permeabilized, blocked and probed with anti-β-catenin antibody. Cells were further incubated with FITC-labelled secondary antibody and then counterstained with Hoechest 33342 (Invitrogen). Images were taken by using a confocal microscope (Laser Scanning. Zeiss 510 Meta).

2.7 Scratch Assay

The spreading and migration capabilities of UMUC3 cells affected by Wnt16 secreted from neighboring fibroblast were assessed in vitro using a scratch wound assay which measures the expansion of a cell population on surfaces.37, 38 The non-contact co-culture system was established with NIH3T3 in the upper chamber and UMUC3 in the bottom chamber of a 24-well plate. The upper chamber NIH3T3 was activated and treated with siCont NP, siWnt NP, siCont NP/ cisplatin and siWnt NP/cisplatin according the procedure described above. A linear wound was generated in the monolayer of UMUC3 with a sterile 200 µl plastic pipette tip upon co-culture. Any cellular debris was removed by washing with PBS and incubated with OptiMEM medium for 20 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Three representative images from each well of the scratched areas under each condition were photographed to estimate the relative migration cells. The data were analyzed using Image J. The experiments were performed at least in duplicate.

2.8 Lentiviral Luciferase Reporter Assays

The activation of Wnt pathway in the neighboring naïve fibroblast by damaged fibroblast was evaluated using TCF/LEF reporter assay.25 To produce stable Wnt-reporter cell lines, NIH3T3 cells were transduced with the Cignal Lenti TCF/LEF Reporter (luc) kit for 48h. Following transduction, the cells were cultured under puromycin selection to generate a homogenous population of transduced cells. Activated NIH3T3 and Wnt-reporter cell lines were seeded on to the upper chamber and lower chamber of the non-direct contact co-culture system respectively. The upper chamber received different treatments as previously mentioned. Four h post co-culture, bottom cells were collected and luciferase assays were performed using a Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

2.9 Tube Formation Assay

The effect of Wnt16 secreted from damaged fibroblast in inducing angiogenesis in neighboring endothelial cells was evaluated by tube formation assay.39, 40 The non-contact co-culture system was established with the upper chamber of activated NIH3T3 receiving different treatments and bottom chamber of HUVEC in a 24 well plate. For the formation of capillary-like structures, 24 well plate were pre-coated using growth factor-reduced matrigel (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). HUVECs (4×104 cells/well) were plated on top of matrigel (280 µL/well). Four h after co-culture, HUVECs were stained by calcein AM (Invitrogen) and visualized under a fluorescence microscope. The number of tubes were quantified by Image J from 5 randomly selected microscopic fields.

2.10 Analyses of Cell Proliferation and Chemotherapy Resistance

All assays were performed at least 3 times and reported as mean values. Assays of cell proliferation were performed with the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) assay with signals captured using a 96-well plate reader. To assess the influence of Wnt16 across a range of cisplatin concentrations, UMUC3 were cultured with recombinant Wnt16 protein (R&D systems) at different concentrations (0.03, 0.3, 3, 6, 12 µg/mL) 6 h prior to cisplatin treatment. Then, cisplatin at a range of concentrations bracketing cell line’s IC50 was added to the medium and incubated for 48h. Cell viability was assayed by MTT. Nonlinear regression curves were plotted using GraphPad Prism. Chemo resistance of bladder cancer cells induced by Wnt16 secreted from fibroblast were performed using UMUC3 cultured with either DMEM, or conditioned medium (CM) generated from active fibroblasts under different treatments (including treatment with siCont NP, siWnt NP, siCont NP/cisplatin, siWnt NP/ cisplatin, cisplatin). The cultured cells received cisplatin treatment for 2 days in the CM with cisplatin at concentrations near UMUC cell line’s IC50 (10 µM). Cell viability was then assayed, and the percentage of viable cells was calculated by comparing each experiment to UMUC3 treated from CM of normal activated NIH3T3 cells. Each assay was repeated a minimum of 3 times with results reported as mean ± SD. For short-term proliferation assay of fibroblast to cisplatin and siRNA treatment, 96-well plates were seeded with 3×103 cells per well NIH3T3 and activated 2h prior to treatment with 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Then, cells were transfected with siWnt NP or siCont NP at different concentrations, or equivalent concentration to 250 nM siRNA. Four h later, cells were washed with PBS and changed into fresh medium or cisplatin at a range of concentration bracketing its IC50. Forty-eight h later, cells were subject to MTT assay described elsewhere.

2.11 Establishment of a non-contact co-culture assay

Co-culture assay was established according to a previous protocol with little adjustment.36 Briefly, NIH3T3 were seeded into a Transwell filter (polycarbonate membrane insert, 0.45 µm pore, Corning Inc.). Before co-culture, UMUC cells, HUVEC cells or naïve NIH3T3 cells were plated onto the bottom of either 6 well, 12 well or 24 well plate at determined density for different experimental purpose. Diameter of NIH3T3 inserts was also chosen accordingly to the size of the well plates. The next day, Transwell insert received different types of treatment. After extensively washing away the reagent-containing medium, fresh medium was added and co-cultured was started by setting the insert on the cell seeded plates. After determined time of co-culture, bottom cells were collected for western-blot analysis, β-catenin nucleus translocation assay, tube formation and other immunofluorescence assay.

2.12 Tumor Growth Inhibition Assay

A stroma-rich bladder cancer model (SRBC) were established as previously reported with little modification.29, 41 In brief, UMUC3 (5×106) and NIH 3T3 (2.5×106) in PBS were subcutaneously co-inoculated into the right flank of mice with Matrigel (BD biosciences, CA) at a ratio of 1:1 (V/V). Small tumor treatments were initiated on the 9th day when the inoculated tumor volume reached 150~200 mm3. Mice were then randomized into 5 groups (n=5~7 per group) as follows: Untreated group (PBS), siCont NP, siWnt NP, cisplatin NP, siWnt NP/ cisplatin NP. IV injections were performed every other days for a total of 5 injections with siRNA dose of 0.6 mg/kg (equivalent to 12 µg siRNA per mice) and cisplatin dose of 1.0 mg/kg. Tumor volume was measured every day with a digital caliper (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg PA) and body weight was also recorded. Tumor volume was calculated as (1/2*length*length*width). Mice were sacrificed one day after the last injection and tumor tissues were collected for further study.

To evaluate the combinatory efficacy on the large tumor, treatments were initiated 14 days post inoculating, when tumor volume reached ~700 mm3 in size. Mice were then randomized into 4 groups (n=5) subjected to the following treatments: PBS, siWnt NP, cisplatin NP and siWnt NP/cisplatin NP respectively. IV injections were performed every day (siRNA 0.6 mg/kg and cisplatin 1.0 mg/kg) with total 4 treatments. Tumor volume and body weight were continuously monitored for another week post last injection to determine combination effect on tumor regression and resistance. Mice in the PBS groups were sacrificed when tumor volume reached ~2,000 mm3.

2.13 In vivo nanoparticle penetration and distribution study

For the study of NP penetration, two types of NP were prepared as follows: firstly, DiI labeled cisplatin NP were prepared by mixing 2% DiI with DOTAP, cholesterol and cisplatin nanocores to formulate the final NP. Secondly, DiI labeled liposomes were prepared by mixing 2% DiI into the lipid membrane and followed by sequential extrusion. The GFP labeled NIH3T3 SRBC models were established as described in the Supplementary Information. Mice were subjected to different treatments. One day post injection, mice were administrated with DiI labeled cisplatin NP or liposomes at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg DiI and were sacrificed 8h post IV injection. Fresh tumor tissues were collected and dissociated as mentioned above. The ratio of cells that took up DiI and ratio of GFP labeled fibroblast that took up DiI were analyzed and quantified by flow cytometry with a BD FACSAria instrument (Beckon Dickinson). For the localization and visualization of NP penetration, tumor was further frozen and sectioned. Frozen tumor sections were fixed with cold methanol for 15 min and 1% triton for 5 min, double stained with CD31 and αSMA primary antibodies at 4°C overnight followed by incubation with FITC-labeled secondary antibody for 1h at room temperature. The sections were also directly stained with DAPI and covered with a coverslip. The sections were observed using a Nikon light microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo). Five randomly selected microscopic fields were quantitatively analyzed by using Image J software.

2.14 Immunohistochemical Staining (IHC) and Immunofluorescence Staining (IF)

IHC of Wnt16. IHC was performed using a standard streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method as previously reported.42 In brief, one day post the small tumor inhibition study on SRBC model, tumor tissues were collected and processed for paraffin sections. Paraffin block sections of SRBC with different treatments were then deparaffinized, antigen recovered, blocked and probed with Wnt16 primary antibody (1:100 dilution) at 4 °C overnight, and then detected using a rabbit specific HRP/DAB detection IHC kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Cell nuclei were counter-stained with hematoxylin. Percentage of Wnt16 coverage were quantified by using Image J on 5 representative microscopic fields. TUNEL assay. Paraffin-embedded tumor sections was deparaffinized and rehydrated. The slides were then stained using a TUNEL assay kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Masson Trichrome Staining. Paraffin-embedded tumor sections was deparaffinized and rehydrated. The slides were then stained using a Masson Trichrome Kit (St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's instruction. IF. Paraffin embedded tissues were prepared by the UNC Tissue Procurement Core and the slices were deparaffinized, antigen recovered, permeabilized and fixed if necessary, and blocked with 1% BSA at room temperature for 1h. Cell markers were detected with antibodies conjugated with fluorophores as indicated. Images were taken using fluorescence microscopy. For the purpose of double staining, primary antibodies with different species origins were applied and different secondary antibodies with non-overlap fluorophores were adopted. For the immunofluorescence staining of in vitro cell samples, cells were fixed with 2% PFA for 15 min, washed, permeabilized, and processed for staining with the same protocol as the in vivo tumor samples. Confocal microscopic images were taken accordingly (Laser Scanning. Zeiss 510 Meta).

2.15 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was undertaken using Prism 5.0c Software. A two-tailed t-test or a one-way analysis of variance was performed when comparing two groups or more than 2 groups, respectively. Statistical significance was defined by a value of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Off-target distribution of cisplatin NP to TAF induces tumor cells resistance via secretion of Wnt16

We have prepared cisplatin NP according to a previous protocol with little adjustment.34 As shown in Fig. 1a, cisplatin NP significantly inhibited growth of a stroma-rich bladder cancer model (SRBC) at a low dose (1 mg/kg) compared with free cisplatin. However, after multiple injections, relapse and resistance occurred in the cisplatin NP treated group. To determine the underlying mechanism of acquired-resistance to cisplatin NP treatment, we examined tissues collected after multiple PBS or cisplatin NP exposures, and observed an elevated levels of Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 16 (Wnt16) in the cisplatin NP treated SRBC tumors (Fig. 1b) but not tumors treated with PBS or free cisplatin. Abnormal Wnt signal activation has been shown to promote tumorigenesis, stemness and resistance in various tumors.43, 44 Among the Wnt family members, Wnt16 is a major secreted factor generated in response to DNA damage.9, 17 Though little information has linked Wnt signaling to cisplatin induced resistance, a previous study demonstrated that Wnt16 expression was induced in prostate and breast cancer fibroblasts in response to chemotherapy-induced DNA damage resulting in cancer cell resistance.9, 45

Figure 1. Off-target delivery of cisplatin NP to TAF induces tumor cells resistance via secretion of Wnt16.

a. Tumor growth inhibition of free cisplatin and cisplatin NP in a stroma rich bladder cancer (SRBC) model (n=5). b. Western blot analysis of Wnt16 protein levels in the resistant tumors. Intensity of the protein bands was quantified by using Image J (n=3, * p<0.05, Student’s t-test). c. Expression level of Wnt16 in different subtypes of bladder cancer. Data were collected and analyzed from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. (* p<0.05, one way ANOVA). d. Dose response curves of UMUC3 cells treated with different levels of recombinant Wnt16 protein (n=4, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, one way ANOVA). IC50 of cisplatin in UMUC3 treated with Wnt16 protein was shown in the inserted figure. eIn vitro western blot analysis of Wnt16 level in cisplatin treated UMUC3, cisplatin treated activated fibroblast NIH3T3 cells and the conditioned medium. f. DiI-labeled cisplatin NP distribution in the SRBC tumor. Tumors were collected 8h post DiI-NP injection. Presentative fluorescence images of TAF (α-SMA: green), blood vessels (CD31: magenta), and DiI-labeled NP (red) and nucleus (DAPI: blue) were shown. Scale Bar equates to 100 µm. g. Quantification of DiI-NP distribution in TAF by flow cytometry. SRBC model was established by co-inoculated UMUC3 with GFP labeled NIH3T3. h. Fluorescence and TUNEL staining of the SRBC tumor after multiple cisplatin NP treatments with α-SMA (red) and apoptotic cells (green). Yellow square boxes highlight the apoptotic fibroblasts (co-stained as yellow). The ratio of apoptotic fibroblasts over all apoptotic cells was calculated. Scale Bar is 100 µm.

The basal-like molecular subtype of bladder cancer has been correlated with increased stromal content and patients with basal-like bladder cancer have a worse overall survival than those with the luminal subtype.46, 47 Interestingly, basal-like bladder tumors have increased levels of Wnt16 (Fig. 1c), indicating a role of Wnt16 in facilitating the progression and resistance of bladder cancer. To examine if Wnt16 is a cause of cisplatin resistance in basal type bladder cancer, we tested the ability of recombinant Wnt16 protein to induce cisplatin resistance in vitro (Fig. 1d). The IC50 of cisplatin to basal type UMUC3 cells continually increased from 12.4 to 30 µM as the concentration of Wnt16 was increased from 0 to 12 µg/mL (Fig. 1d). To evaluate whether the effective concentration of Wnt16 that induced cisplatin resistance in vitro (Fig. 1d) was physiologically relevant, we quantified the concentration of Wnt16 upregulated by cisplatin NP in vivo. Wnt16 concentrations in cisplatin NP treated tumors (approximately 6.5 µg/ml) was well within the range of concentrations of Wnt16 that were sufficient to induce cisplatin resistance (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, cisplatin NP treatment induced Wnt16 secretion, leading to chemotherapy resistance of tumor cells.

Tumors are heterogeneous, therefore we next sought to determine the cellular origin of Wnt16 production within tumors. Wnt16 expression has been detected on uterine stroma and was overexpressed by DNA damaged stromal cells surrounding prostate tumors.9, 48 To examine whether stromal cells were responsible for Wnt16 upregulation in our SRBC model, we treated the major cellular components of the SRBC model (UMUC3 cells and the mouse fibroblast NIH3T3) in vitro with cisplatin. In order to mimic in vivo TAF, NIH3T3 was pre-conditioned with TGF-β to obtain a TAF-like phenotype. We found elevated amounts of Wnt16 in both cell lysate and conditioned medium from TGF-β activated NIH3T3 cells after exposure to either free cisplatin or cisplatin NP treatment (Fig. 1e). In contrast, Wnt16 expression was not induced in UMUC3 cells or other epithelial cancer cell lines (Fig. 1e and supplementary Fig. S3). To further confirm the origin of the upregulated Wnt16 level in vivo, a UMUC3 tumor model was developed without the addition of NIH3T3. This model showed a low TAF level. Cisplatin NP failed to induce Wnt16 in the UMUC3 model further indicating the TAF-origin of Wnt16 (supplementary Fig. S4). The fact that Wnt16 upregulation is not the result of exogenously added NIH3T3 fibroblasts comes from the observation that a patient derived xenograft model of human bladder cancer also responded to repeated cisplatin NP challenges by upregulating Wnt16 (supplementary Fig. S5). Therefore, consistent with previous reports, our studies confirm that cisplatin induces Wnt16 in TAF, rather than cancer cells. To evaluate the intratumoral distribution of cisplatin NP and in particular its relationship with increased expression level of Wnt16, cisplatin NP were labeled with DiI and intravenously (IV) injected into SRBC model mice. Flow cytometry was used to quantify DiI particle uptake in different cell types in the SRBC model 8h after injection. As shown in Fig. 1g, approximately 23.3% of TAF internalized DiI NP. The distribution of DiI NP was further confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of different intratumoral cell types. We saw TAF located in close proximity to blood vessels were able to take up cisplatin NP (Fig. 1f), indicating that cisplatin NP, which were originally designed to target tumor cells, could off-targetedly distribute to fibroblast cells. Western-blot analysis further confirmed the expression of sigma-receptors on activated TAF, which explained the positive internalization of cisplatin NP by TAF (Supplementary Fig. S6). Since Wnt16 was reported as a secreted factor in response to damage9, we next evaluated whether cisplatin NP induced TAF’ damage and consequently leading to Wnt16 secretion. We observed that, after multiple injections, cisplatin NP were able to induce apoptosis in both TAF and tumor cells with approximately half of the apoptotic cells being TAF (Fig. 1h). Therefore, we conclude that cisplatin NP are taken up by TAF, inducing apoptosis and the secretion of Wnt16 to promote (in a paracrine fashion) cisplatin resistance in tumor cells.

3.2 Wnt16 knockdown inhibits growth and invasion of neighboring bladder cancer cells

We hypothesized that the combined delivery of cisplatin NP along with siRNA targeting Wnt16 to fibroblasts would lead to enhanced anti-tumor efficacy. We encapsulated siRNA against Wnt16 into liposome-hyaluronic acid- protamine nanoparticles (LPH NP) as previously described (siWnt NP) (Supplementary Fig. S1).32 In order to improve fibroblast internalization and ensure we were knocking down Wnt16 in the fibroblast population and not the UMUC3 cells, we took the following into consideration: firstly, anisamide was conjugated onto LPH to improve its internalization, since TAF also express high levels of sigma receptor (Supplementary Fig. S6). Secondly, since the fibroblast cells are of mouse origin and the cancer cells are of human origin, we used mouse specific siRNA (with four mismatches with the human sequence) to increase the selectivity for Wnt16 knockdown. Based on these assumptions, as expected, we confirmed that LPH NP loaded with mouse anti-Wnt16 siRNA was able to decrease cisplatin induced Wnt16 protein levels in activated NIH 3T3 cells but did not have any effect in UMUC3 cells (Supplementary Fig. S7), confirming that siRNA delivered by LPH NP could specifically knockdown mouse, but not human, Wnt16. To confirm that the effects of Wnt16 knock-down were working in a paracrine manner, conditioned medium from fibroblasts with different treatments were added to cisplatin (10 µM) treated UMUC3 cells. As expected, conditioned medium from cisplatin treated fibroblasts showed 1.2–1.5 fold (p<0.05) higher activity in protecting UMUC3 cells from cisplatin induced cell death compared to conditioned medium without cisplatin treatment. Such activity was abolished if the fibroblasts were also treated with siWnt NP (Fig. 2a). These experiments indicate that Wnt16 secreted from cisplatin damaged fibroblasts is both necessary and sufficient to induce resistance in a paracrine manner in neighboring cancer cells.

Figure 2. Influences of specific Wnt16 knockdown on the neighboring tumor cells and fibroblasts.

a. Cell viability (48h) of UMUC3 towards cisplatin (10 µM) when treated with different NIH3T3 conditioned medium (CM) (n=4, * p <0.05, ** p<0.01, one way ANOVA). b. A non-contact co-culture system was established with the upper chamber seeded with activated NIH3T3 of different treatments, and the lower chamber seeded with naïve UMUC3. This system was used in the scratch assay, β–catenin translocation assay and western blot. c. Scratch assay using the non-contact co-culture system with upper chamber NIH3T3 and lower UMUC3. * Moving distance of lower chamber UMUC3 compared to 0h, n=3. Scale bar is 100 µm. d. Confocal images of β-catenin nucleus translocation (Scale bars 20 µm) in low chamber UMUC3. e. Western blot analysis of Wnt pathway down-stream proteins (c-myc and cyclin D1), EMT markers (E-cadherin (E-cad) and N-cadherin (N-cad)) and apoptotic marker (cleaved PARP) in the lower UMUC3 chamber. f. A non-contact co-culture system was established with the upper chamber seeded with activated NIH3T3 and the lower chamber seeded with naïve activated NIH3T3. g. Assay of canonical Wnt pathway signaling through activation of luciferase labelled fibroblasts was performed in the lower chamber. Four h after co-culture, relative luciferase units (RLU) were quantified. Data are mean ± SD, n=3. h. Western blot analysis of a major ECM glycoprotein, fibronectin, level in the lower chamber 24h post co-culture. i. Confocal images of immunofluorescence staining of fibronectin in the lower chambers (fibronectin: green, cell nucleus: blue), scale bar represents 20 µm. j. Cell proliferation of activated NIH3T3 transfected with anti-Wnt16 or control siRNA at different concentrations (n = 4). k. Viability of activated NIH3T3 across a range of cisplatin concentrations with transfection of anti-Wnt16 or control siRNA (concentration of siRNA was 180 nM). (n=4, * p<0.05, Student’s t-test). Data points show mean ± SD.

We next sought to determine the possible mechanisms. A non-contact co-culture system of NIH3T3 and UMUC3 was established using a Transwell configuration (Fig. 2b).36 Previous studies indicated that the secreted Wnt16 mainly activates the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway.9, 49 In an attempt to confirm that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in UMUC3 cells was activated by the Wnt16 secreted from cisplatin treated fibroblast in the upper chamber, immunofluorescence was used to visualize β-catenin localization in UMUC3 cells in the lower chamber at different time points after co-culture.35 As shown in Fig. 2d, β-catenin was primarily membranous during the initial 2h of co-culture, however, cisplatin NP treated NIH3T3 cells promoted both increased β-catenin abundance but also nuclear localization in UMUC3 cells particularly at 4h after co-culture. As expected, siWnt NP treatment of fibroblasts prohibited nuclear translocation of β-catenin in the UMUC3 cells. In addition, known β-catenin downstream targets, including c-Myc and Cyclin-D1, were significantly up-regulated in the cancer cells co-cultured with cisplatin treated fibroblasts (Fig. 2e).50, 51 The expression of these two proteins slightly decreased after co-culturing with fibroblasts with treated siWnt NP alone or in combination with cisplatin. Control siRNA NP (siCont NP) and human specific siRNA NP were set as controls and no biological function was found.

We then studied the paracrine function of Wnt16 on tumor cells. Apoptotic responses measured by cleavage of the major apoptotic protein PARP were investigated and further indicated that co-culture of UMUC3 cells with cisplatin treated NIH3T3 cells substantially attenuated cisplatin induced apoptosis (Fig. 2e). The Wnt signaling pathway is known to enhance cell motility and invasiveness via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).9, 35 Recently, EMT has been considered to be one of the major mechanisms for cisplatin induced resistance in pancreatic cancer.52 Loss of E-cadherin and gain of N-cadherin expression are the main characteristics of EMT.9 When the lower chamber UMUC3 cells were exposed to cisplatin treated NIH3T3 cells in the upper chamber, E-cadherin was downregulated and N-cadherin was upregulated consistent with EMT in UMUC3 cells. This EMT phenotype was abolished when UMUC3 cells were exposed to siWnt NP treated fibroblasts (Fig. 2e). EMT is also an indication of tumor cell mobility. A scrape assay was performed to evaluate the mobility of cells using the same non-contact co-culture system. Twenty h after co-culture, NIH3T3 cells treated with cisplatin enhanced the mobility of neighboring UMUC3 cells in the lower chamber, while Wnt16 downregulation in the upper fibroblasts could inhibit this movement (Fig. 2c).

3.3 Wnt16 knockdown modulates the biological function of neighboring TAF and their sensitivities to cisplatin

TAF not directly treated by cisplatin NP (hereafter referred to as naïve TAF) were also affected by paracrine Wnt16 secreted from cisplatin treated fibroblasts. To determine if Wnt signaling was activated in the neighboring naïve TAF, we generated an activated NIH3T3 cell strain with stable expression of Wnt reporter using a Cignal Lenti T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor (TCF/LEF) Reporter Kit and seeded these cells on the lower chamber of the non-contact co-culture system (Fig. 2f). Results indicated that cisplatin treated TAF in the upper chamber of the system could activate the canonical Wnt signaling in the lower chamber naïve fibroblasts (Fig. 2g). Enhanced luciferase intensity was observed 4h after co-culture, which was temporally consistent with the fibroblasts in the lower chamber stimulated directly by Wnt16 recombinant protein. siWnt, but not siCont, NP suppressed the expression of Wnt16 and completely blocked the activation of β-catenin signaling (Fig. 2g). Fibronectin is secreted from functional TAF and has been shown to increase extracellular matrix (ECM) rigidity and promote tumor malignancy.53 Since fibronectin expression is closely regulated by the canonical β-catenin mediated Wnt pathway, fibronectin levels can serve as an important indicator to evaluate the relationship of Wnt16 knockdown on ECM remodeling.54 We found that fibronectin levels were upregulated in cisplatin treated naïve fibroblasts relative to the untreated fibroblasts (Fig. 2h). Moreover, siWnt16, but not siCont, NP treatment in the upper chamber cells inhibited the expression of fibronectin of naïve TAF in the lower chamber (Fig. 2h). This observation was further confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of fibronectin in the lower chamber (Fig. 2i). Finally, an MTT assay was carried out to show that a deficiency of Wnt16 did not influence the cell viability of the activated fibroblasts (Fig. 2j). This finding further confirmed that Wnt16 protein did not play a pro-proliferative or pro-apoptotic role in regulating fibroblasts growth, but rather protects the cells from cisplatin induced cell death. In keeping with this notion, the combination treatment of activated fibroblasts with siWnt, but not siCont NP, and cisplatin facilitated cell death (Fig. 2k).

3.4 Single dose cisplatin NP attenuates TME function and improves NP penetration

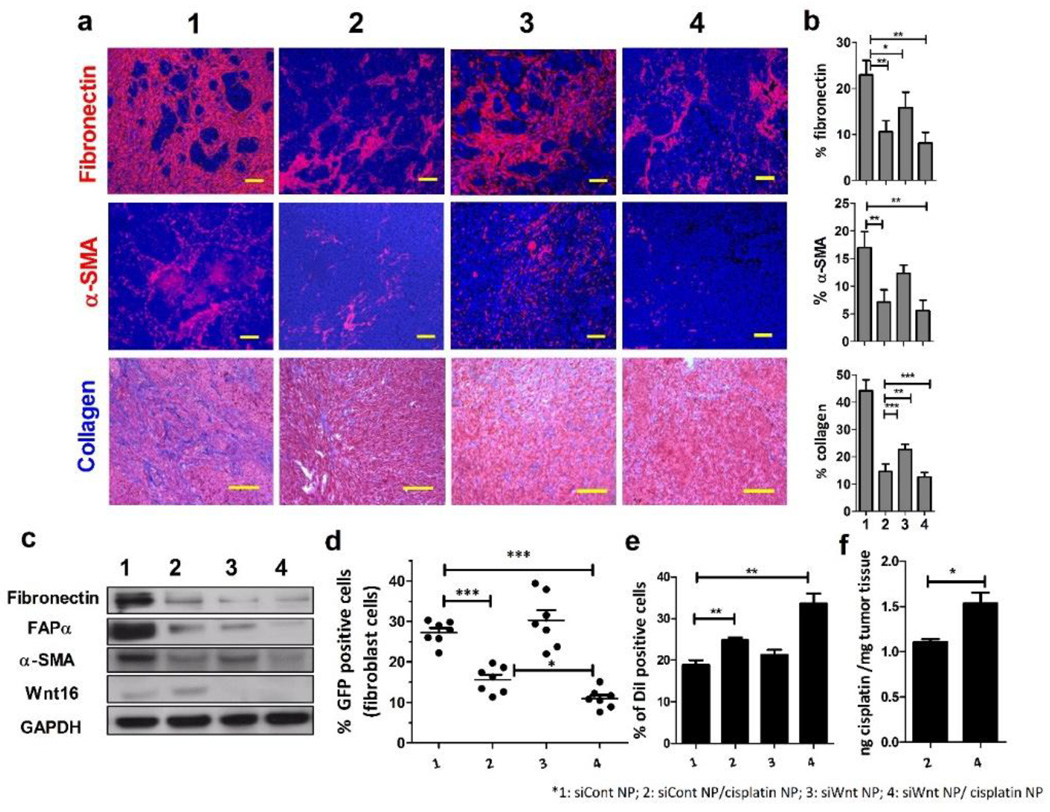

Based upon our in vitro results, we hypothesized that while cisplatin NP taken up by TAF leads to rapid fibroblast death.30, damaged fibroblasts could promote the survival of surviving TAF. To confirm that cisplatin could remodel the TME in vivo, single dose and multiple dose siCont NP/cisplatin NP treatments were carried out in our SRBC model (siCont NP were set as control for siWnt NP treatment and showed no therapeutic interference, and thereafter, instead of mentioning siCont NP/cisplatin treatment, we directly referred to it as cisplatin NP treatment). Both tumor growth dynamics and NP distribution kinetics were monitored. Consistent with a previous study by Zhang et al, a single dose of cisplatin NP was efficient in remodeling the TME for improved NP penetration and therapeutic outcome.29 Representative immunostaining images in Fig. 3a showed that cisplatin NP significantly reduced the expression level of fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (a marker of TAF activation) relative to control treatment (siCont NP). Fibronectin facilitates the deposition and crosslinking of collagen and elastin.53, 55 Therefore, consistent with decreasing fibronectin, both collagen content and collagen crosslinking were reduced in the cisplatin NP treated groups (Fig. 3a and b). The changes in expression levels of major ECM proteins were further confirmed by western blot (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Single dose cisplatin NP attenuate TME function and improve NP penetration.

Single dose siCont NP (1), cisplatin NP/siCont NP (2), siWnt NP (3) and cisplatin NP/siWnt NP (4) were IV administered to mice separately with cisplatin 1.0 mg/kg and siRNA 0.6 mg/kg. Tissues were collected 2 days after injections. a. Immunofluorescence staining of fibronectin, α-SMA. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) and fibronectin and α-SMA were stained red. Another ECM component, collagen, was stained by using Masson trichrome. The blue color represents collagen content, while the cytoplasm is stained red. Scale bar is 100 µm. b. Quantitative analysis of fibronectin, α-SMA and collagen content using Image J from 5 randomly selected microscopic fields. (n=5, * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test) c. Western blot analysis of FAP α, α-SMA, fibronectin and Wnt16 protein levels in the tumors two days after single dose NP treatment. d. NIH3T3 in the SRBC model was further labeled with GFP. The ratio of GFP positive TAF was quantified by flow cytometry two days after NP treatment. (n=8, *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test) e. DiI-labeled liposomes (~70nm) were IV injected one day before sacrificing the mice. Fluorescent liposome accumulations and penetrations in the SRBC tumors were quantified by flow cytometry (n=3, ** p<0.01, Student’s t-test). f. The amount of accumulated platinum in cisplatin NP/siCont NP (2) and cisplatin NP/siWnt NP (4) were measured by ICP-MS and shown as ng cisplatin/mg tumor tissue. (n=3, * p<0.05, Student’s t-test). Data in all charts show mean ± SD.

We next sought to determine the influence of TAF on ECM remodeling after a single dose cisplatin NP therapy. A SRBC model was developed by co-inoculating a green fluorescence protein (GFP) labeled NIH3T3 cells with UMUC3 cells. Notably, survival of GFP+ fibroblasts decreased significantly in the cisplatin NP treated group compared to other treatment groups (Fig. 3d). This result suggested that a single dose of cisplatin NP could significantly deplete TAF, reducing the secretion of ECM proteins and effectively disrupting the ECM structure. Based on previous studies of the tumor interstitial matrix, we further hypothesized that a decrease in collagen content would improve the intratumoral distribution of NP.7, 56 Therefore, we quantitatively measured the intratumoral distribution of DiI-labeled liposomes (70 nm in diameter) in the SRBC model with the aforementioned single dose treatments via flow cytometry. Consistent with our hypothesis, an improved NP accumulation and penetration was observed in the cisplatin NP treated group compared to the control group (siCont NP) (Fig. 3e). Improved NP penetration was an indication of better therapeutic effect. Since naïve tumors maintained a basal level expression of Wnt16, single dose of siWnt NP could also improve NP penetration and tumor inhibition effect. Instead of depleting TAF, downregulation of Wnt16 decreased the expression of α-SMA and fibronectin, consequently reducing the content of collagen (Fig. 3a, b). Combinatory cisplatin NP and siWnt NP treatment was slightly more effective than single cisplatin NP treatment alone (Supplementary Fig. S9).

3.5 siWnt NP overcome the cisplatin NP induced TME stiffening after multiple doses and improve the overall NP accumulation

Although a single dose of cisplatin NP demonstrated efficient killing in both tumor cells and TAF, the tumor still relapsed after repeated treatments (Fig. 1a). The resistant phenotype was acquired in both tumor cells and neighboring TAF (Fig. 4a and c). To examine the acquired resistance in TAF and the TME, the SRBC models were dosed multiple times of cisplatin NP or siWnt NP. After 4 doses, the Wnt16 expression level was significantly elevated in the cisplatin NP group (Fig. 4c). Consistently, expression of α-SMA, fibroblast activation protein α (FAPα) and fibronectin were also elevated (Fig. 4a, b and c). Collagen content was also upregulated after multiple cisplatin NP treatments (Fig. 4a and b). Notably, these changes in the TME after repeated dosing was different from the changes in the single dose treatment, which showed a decrease in TAF and the ECM. This trend indicates the gradual development of acquired resistance in the TME. The resistance of TAF to cisplatin NP after multiple doses was assessed by quantitative analysis of the GFP+ fibroblast percentage in residual tumors by flow cytometry. In contrast to the decreasing of GFP+ cell ratio found in the single dose cisplatin NP treatment (Fig. 3d), the survival ratio of GFP+ fibroblasts increased by ~2-fold after repeated cisplatin NP dosing (Fig. 4d). Consequently, the content of cisplatin in the residual tumor remained at almost the same level with that of single dose (Fig. 3f and Fig. 4f). Conversely, both multiple dose siWnt NP and siWnt NP/cisplatin NP treatments inhibited the changing of the TAF ratio in the tumor and remodeled the TME by significantly decreasing α-SMA, FAPα, fibronectin and collagen content (Fig. 4a and c). Notably, the combination of cisplatin NP with siWnt NP could reverse the cisplatin induced resistance, increase DiI labeled liposome penetration by ~2-fold (Fig. 4e), and promote the accumulation of cisplatin by ~3-fold (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4. siWnt NP overcome the cisplatin NP induced TME stiffening after multiple doses and improve the overall NP accumulation.

siCont NP (1), cisplatin NP/siCont NP (2), siWnt NP (3) and cisplatin NP/siWnt NP (4) were IV administered to mice separately with cisplatin 1.0 mg/kg and siRNA 0.6 mg/kg, every other day for a total of 4 injections. a. Immunofluorescence staining of fibronectin (red), α-SMA (red) and cell nucleus (DAPI: blue). Collagen was stained via Masson trichrome staining (blue). Scale bar represents 100 µm. b. Quantitative analysis of fibronectin, α-SMA and collagen content using Image J from 5 randomly selected microscopic fields. (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test) c. Western-blot analysis of FAPα, α-SMA, fibronectin and Wnt16 levels in the tumors 2 days after multiple NP treatment. d. NIH3T3 in the SRBC model was further labeled with GFP. The ratio of GFP positive TAF was quantified by flow cytometry 2 days after NP treatment. (*** indicated p<0.001, Student’s t test, n=8) e. DiI-labeled liposomes (~70nm) were IV injected 1 day before sacrificing the mice. Fluorescent liposome accumulations and penetrations in the SRBC tumors were quantified by flow cytometry (** p<0.01, Student’s t-test, n=3). f. The amount of accumulated platinum in cisplatin NP/siCont NP (2) and cisplatin NP/siWnt NP (4) were measured by ICP-MS and shown as ng cisplatin/mg tumor tissue (*p<0.05, Student’s t-test, n=3). Data in all charts show mean ± SD.

3.6 Wnt16 knockdown attenuates cisplatin NP induced angiogenesis

A recent study showed that a plasmid-encoding Wnt16 gene accelerated tube formation in cultured primary mouse cavernous endothelial cell (MCECs), suggesting a role in cavernous angiogenesis.57–59 Therefore, we further hypothesized that knockdown of Wnt16 could also inhibit angiogenesis. Data in our study showed that both Wnt16 secreted from NIH3T3 fibroblasts (using the non-contact co-culture system) and recombinant Wnt16 protein induced tube formation of human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. S8). Downregulating Wnt16 using siWnt NP also downregulated angiogenesis and vascular remodeling in the SRBC model in vivo after multiple doses (Fig. 5c, d). Since angiogenesis accelerates tumor progression, it is highly likely that the anti-angiogenesis caused by siWnt NP is one of the reasons for its efficient tumor inhibitory effect.35 Inhibition of angiogenesis, though, weakens the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and compromises NP-mediated drug delivery efficiency.60 However, multiple doses of cisplatin NP/siWnt NP, promoted the penetration of both DiI labeled liposomes (Fig. 4e) and cisplatin NP (Fig. 5e, f) compared to the cisplatin NP alone group. Decreased stroma density by siWnt16 NP might contribute to the improved NP penetration. In addition, siWnt NP treatment might prune immature vessels and remodels the vasculature to more closely resemble the structure of normal vessels. This so-called “tumor vessel normalization” not only benefits the delivery of small molecule chemo drugs to tumors, but also benefits the accumulation of soft NP like liposomes (less than 100 nm) and small, solid NP like cisplatin NP. This is consistent with previous findings reported by Jain et al and Kataoka et al.60–62

Figure 5. Wnt16 downregulation attenuates cisplatin NP induced angiogenesis for bladder cancer treatment.

A non-contact co-culture study was performed to evaluate tube formation in vitro. The upper chamber NIH3T3 cells were given different treatments and co-cultured with HUVEC cells seeded in the lower chambers. Tube formation was monitored in HUVEC cells as indicators for angiogenesis 4h after co-culture. HUVEC cells were stained by calcium AM (green) (a) and the number of formed tubes was calculated (b). Five randomly selected microscopic fields were quantitatively analyzed by Image J (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test). Scale bar represents 100 µm. Influence on angiogenesis was further evaluated in vivo by immunofluorescence staining endothelial cells with CD31 (red) after multiple treatments (c). Quantitative analysis was calculated based on 5 randomly selected microscopic fields (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, Student’s t-tests, scale bar indicates 100 µm) (d). Distribution of DiI labeled cisplatin NP 8h after IV injection in different treatments of the SRBC model (e). Five images were quantified and the result is shown on right (* p<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, Student’s t-tests) (f).

3.7 Intravenous administration of siWnt NP with cisplatin NP effectively inhibited SRBC tumor growth at early or late stage

The efficacy of systemically delivering siWnt NP in combination with cisplatin NP was evaluated at different tumor stages in the SRBC model. An early stage SRBC model was established with tumor sizes around 150–200 mm3 and treatments were given every other day (Fig. 6a). Cisplatin NP could partially inhibit tumor growth. Whereas, the combination of cisplatin NP and siWnt NP effectively inhibited solid tumor growth (Fig. 6a, p<0.001). siCont had no influence on tumor growth, ruling out any effect from the delivery vehicle itself. The efficacy was further evaluated on a late-stage SRBC tumor when the tumors developed to size around 700 mm3. Daily injections were carried out to ensure a better therapeutic outcome. As shown in Fig. 6b, both cisplatin NP and siWnt NP showed a mild tumor inhibition effect. However, the combinatory therapy presented potent efficacy in the large tumor treatment. It could effectively shrink the tumor and delay tumor growth for almost one week after the last injection. No decrease in body weight and no abnormal blood parameters were observed in any of the groups (Supplementary Fig. S10–12, Table. S1). To demonstrate that tumor growth inhibition in the siWnt NP treated group and the combinatory group was the result of Wnt16 downregulation, we measured the level of Wnt16 after treatments.

Figure 6. IV injection of siWnt NP with cisplatin NP inhibited SRBC tumor growth.

a. IV injection of siWnt NP with cisplatin NP inhibited SRBC tumor growth when the first injection started on day 9 post inoculation (small tumor volume ~150 mm3, n=5–7). Data show mean ± SD (** p<0.01; *** p<0.001, ns, no significant difference, one way ANOVA). b. IV injection of siWnt NP with cisplatin NP led to tumor regression when the first injection started on day 14 post inoculation (large tumor volume ~700 mm3, n=4). c. Scheme of the proposed hypothesis. d. Immunohistochemistry staining of Wnt16 on tumor tissues at the end point of small tumor inhibition study. Wnt16 was stained brown and the cell nuclei were stained blue. The scale bar represents 100 µm. The Wnt16 content of 5 randomly selected microscopic fields was quantified using Image J. The quantification bar chart is shown on right (** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test). e. Western blot analysis of Wnt16 levels in tumors after treatment. Three samples were taken randomly from three mice in each treatment group. The intensity of the Wnt16 western band was analyzed by Image J and calculated based on content of GAPDH. Quantification is shown on right. * p<0.05, Student’s t-test. f. Effect of NP on the SRBC model apoptosis using TUNEL assay. Five images were quantified and the data is shown on right (* p<0.01, *** p<0.001, Student’s t-test). Same scale bar used as d.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) images showed an effective silencing of Wnt16 expression in the combination group approximately 4 to 5-fold compared to cisplatin NP treated groups (Fig. 6d). Western blot results were consistent with the IHC data (Fig. 6e). In addition, siWnt NP could also sensitize SRBC model towards cisplatin NP treatment and lead to extensive apoptosis (p<0.05) accounting for the better therapeutic outcome in the combinatory treatment (Fig. 6f, supplementary Fig. S13).

4. Conclusions

Our experimental results suggest that off-target distribution of chemotherapeutic NP to TAF could lead to contradictory effects. Internalization of cisplatin into TAF resulted in their immediate killing, blocking the secretion of stroma factors (e.g. fibronectin) and violating the communication between fibroblasts and tumor cells, subsequently inhibited tumor growth. However, chronic exposure of TAF to cisplatin activated the damage response program and promoted the secretion of survival proteins, such as Wnt16, leading to tumor cell resistance and metastasis, stroma reconstruction and angiogenesis (Fig. 6c). Our studies underscore the importance of TAF as both biological supporters for tumor growth, metastasis as well as a physical barrier for NP penetration and therapeutic outcome. Our study provides guidance and implications for the design of tumor-targeted delivery of therapeutic NP. We focused on the off-target distribution of NP into non-tumor stroma cells and showed the importance of NP stroma distribution in acquired resistance and limited NP penetration. Our findings suggest that major survival factors in response to damage play significant roles in TAF mediated acquired resistance. Blocking such factors benefits both the pharmacological activities as well as the drug delivery efficiency of the NP delivered chemodrugs and leads to improved therapeutic outcome. Therefore, exploring the major secreted survival factors in tumor-stroma crosstalk and co-delivering two regiments that could kill the fibroblasts as well as inhibit the secretion of these major factors would be of significant clinical potential. We anticipate our study will serve as a gateway for future development of NP to explore the complicated tumor microenvironment. The current study also demonstrated the power of nanotechnology for studying the role of TME in chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by NIH grants CA149363, CA149387, CA151652, and DK100664. We thank Andrew Blair for his assistance in preparing the manuscript. We thank Jordan Kardos who did the bioinformatic analysis for the Wnt16 data in different subtypes of bladder cancer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wu Y, Guo L, Liu J, Liu R, Liu M, Chen J. [The reversing and molecular mechanisms of miR-503 on the drug-resistance to cisplatin in A549/DDP cells] Zhongguo fei ai za zhi = Chinese journal of lung cancer. 2014;17:1–7. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2014.01.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch M, Krieger ML, Stolting D, Brenner N, Beier M, Jaehde U, Wiese M, Royer HD, Bendas G. Overcoming chemotherapy resistance of ovarian cancer cells by liposomal cisplatin: molecular mechanisms unveiled by gene expression profiling. Biochemical pharmacology. 2013;85:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drayton RM, Catto JW. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2012;12:271–281. doi: 10.1586/era.11.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piulats JM, Jimenez L, Garcia del Muro X, Villanueva A, Vinals F, Germa-Lluch JR. Molecular mechanisms behind the resistance of cisplatin in germ cell tumours. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. 2009;11:780–786. doi: 10.1007/s12094-009-0446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correia AL, Bissell MJ. The tumor microenvironment is a dominant force in multidrug resistance. Drug Resist Update. 2012;15:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng H, Zhao Y, Dong J, Xue M, Lin YS, Ji Z, Mai WX, Zhang H, Chang CH, Brinker CJ, Zink JI, Nel AE. Two-wave nanotherapy to target the stroma and optimize gemcitabine delivery to a human pancreatic cancer model in mice. ACS nano. 2013;7:10048–10065. doi: 10.1021/nn404083m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diop-Frimpong B, Chauhan VP, Krane S, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Losartan inhibits collagen I synthesis and improves the distribution and efficacy of nanotherapeutics in tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2909–2914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert LA, Hemann MT. DNA damage-mediated induction of a chemoresistant niche. Cell. 2010;143:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Campisi J, Higano C, Beer TM, Porter P, Coleman I, True L, Nelson PS. Treatment-induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1359–1368. doi: 10.1038/nm.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ries CH, Cannarile MA, Hoves S, Benz J, Wartha K, Runza V, Rey-Giraud F, Pradel LP, Feuerhake F, Klaman I, Jones T, Jucknischke U, Scheiblich S, Kaluza K, Gorr IH, Walz A, Abiraj K, Cassier PA, Sica A, Gomez-Roca C, de Visser KE, Italiano A, Le Tourneau C, Delord JP, Levitsky H, Blay JY, Ruttinger D. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages with anti-CSF-1R antibody reveals a strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer cell. 2014;25:846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavora B, Reynolds LE, Batista S, Demircioglu F, Fernandez I, Lechertier T, Lees DM, Wong PP, Alexopoulou A, Elia G, Clear A, Ledoux A, Hunter J, Perkins N, Gribben JG, Hodivala-Dilke KM. Endothelial-cell FAK targeting sensitizes tumours to DNA-damaging therapy. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, Cooper ZA, Chapman PB, Solit DB, Ribas A, Lo RS, Flaherty KT, Ogino S, Wargo JA, Golub TR. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang Y, Zuka M, Perez-Pinera P, Astudillo A, Mortimer J, Berenson JR, Deuel TF. Secretion of pleiotrophin stimulates breast cancer progression through remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:10888–10893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704366104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reedijk J, Lohman PH. Cisplatin: synthesis, antitumour activity and mechanism of action Pharmaceutisch weekblad. Scientific edition. 1985;7:173–180. doi: 10.1007/BF02307573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshikawa A, Saura R, Matsubara T, Mizuno K. A mechanism of cisplatin action: antineoplastic effect through inhibition of neovascularization. The Kobe journal of medical sciences. 1997;43:109–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binet R, Ythier D, Robles AI, Collado M, Larrieu D, Fonti C, Brambilla E, Brambilla C, Serrano M, Harris CC, Pedeux R. WNT16B is a new marker of cellular senescence that regulates p53 activity and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9183–9191. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos AR, Campisi J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:973–979. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien Y, Scuoppo C, Wang X, Fang X, Balgley B, Bolden JE, Premsrirut P, Luo W, Chicas A, Lee CS, Kogan SC, Lowe SW. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-kappaB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes & development. 2011;25:2125–2136. doi: 10.1101/gad.17276711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bavik C, Coleman I, Dean JP, Knudsen B, Plymate S, Nelson PS. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer research. 2006;66:794–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:12072–12077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211053698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS. Genetic heterogeneity and cancer drug resistance. The lancet oncology. 2012;13:e178–e185. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen Y, Wang CT, Ma TT, Li ZY, Zhou LN, Mu B, Leng F, Shi HS, Li YO, Wei YQ. Immunotherapy targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor growth and increases survival in a murine colon cancer model. Cancer science. 2010;101:2325–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaler P, Owusu BY, Augenlicht L, Klampfer L. The Role of STAT1 for Crosstalk between Fibroblasts and Colon Cancer Cells. Frontiers in oncology. 2014;4:88. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermeulen L, De Sousa EMF, van der Heijden M, Cameron K, de Jong JH, Borovski T, Tuynman JB, Todaro M, Merz C, Rodermond H, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Richel DJ, Stassi G, Medema JP. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo S, Miao L, Wang Y, Huang L. Unmodified drug used as a material to construct nanoparticles: delivery of cisplatin for enhanced anti-cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2014;174:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo S, Wang Y, Miao L, Xu Z, Lin CM, Zhang Y, Huang L. Lipid-coated Cisplatin nanoparticles induce neighboring effect and exhibit enhanced anticancer efficacy. ACS nano. 2013;7:9896–9904. doi: 10.1021/nn403606m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS letters. 1990;268:235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Miao L, Guo S, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Satterlee A, Kim WY, Huang L. Synergistic anti-tumor effects of combined gemcitabine and cisplatin nanoparticles in a stroma-rich bladder carcinoma model. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2014;182:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Undzys E, Holwell N, Foltz WD, Li SD. Docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles that target alpha-smooth muscle actin-expressing stromal cells suppress breast cancer metastasis. Cancer research. 2013;73:4862–4871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology. 2011;8:97–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Xu Z, Guo S, Zhang L, Sharma A, Robertson GP, Huang L. Intravenous delivery of siRNA targeting CD47 effectively inhibits melanoma tumor growth and lung metastasis. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21:1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee R, Tyagi P, Li S, Huang L. Anisamide-targeted stealth liposomes: a potent carrier for targeting doxorubicin to human prostate cancer cells. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2004;112:693–700. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lei Miao SG, Zhang Jing, Kim William Y, Huang Leaf. Nanoparticles with Precise Ratiometric Co-loading and Co-delivery of Gemcitabine Monophosphate and Cisplatin for Treatment of Bladder Cancer. AFM. 2014 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu L, Zhang C, Zhang LY, Dong SS, Lu LH, Chen J, Dai Y, Li Y, Kong KL, Kwong DL, Guan XY. Wnt2 secreted by tumour fibroblasts promotes tumour progression in oesophageal cancer by activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway. Gut. 2011;60:1635–1643. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.241638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umezu T, Ohyashiki K, Kuroda M, Ohyashiki JH. Leukemia cell to endothelial cell communication via exosomal miRNAs. Oncogene. 2013;32:2747–2755. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nature protocols. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viticchie G, Lena AM, Latina A, Formosa A, Gregersen LH, Lund AH, Bernardini S, Mauriello A, Miano R, Spagnoli LG, Knight RA, Candi E, Melino G. MiR-203 controls proliferation, migration and invasive potential of prostate cancer cell lines. Cell cycle. 2011;10:1121–1131. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.7.15180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benndorf RA, Schwedhelm E, Gnann A, Taheri R, Kom G, Didie M, Steenpass A, Ergun S, Boger RH. Isoprostanes inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration, tube formation, and cardiac vessel sprouting in vitro, as well as angiogenesis in vivo via activation of the thromboxane A(2) receptor: a potential link between oxidative stress and impaired angiogenesis. Circulation research. 2008;103:1037–1046. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnaoutova I, Kleinman HK. In vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nature protocols. 2010;5:628–635. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miao L, Guo S, Zhang J, Kim WY, Huang L. Nanoparticles with Precise Ratiometric Co-Loading and Co-Delivery of Gemcitabine Monophosphate and Cisplatin for Treatment of Bladder Cancer. Advanced functional materials. 2014;24:6601–6611. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Peng L, Mumper RJ, Huang L. Combinational delivery of c-myc siRNA and nucleoside analogs in a single, synthetic nanocarrier for targeted cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8459–8468. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fodde R, Brabletz T. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cancer stemness and malignant behavior. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cui J, Jiang W, Wang S, Wang L, Xie K. Role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in drug resistance of pancreatic cancer. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18:2464–2471. doi: 10.2174/13816128112092464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi W, Porten S, Kim S, Willis D, Plimack ER, Hoffman-Censits J, Roth B, Cheng T, Tran M, Lee IL, Melquist J, Bondaruk J, Majewski T, Zhang S, Pretzsch S, Baggerly K, Siefker-Radtke A, Czerniak B, Dinney CP, McConkey DJ. Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volkmer JP, Sahoo D, Chin RK, Ho PL, Tang C, Kurtova AV, Willingham SB, Pazhanisamy SK, Contreras-Trujillo H, Storm TA, Lotan Y, Beck AH, Chung BI, Alizadeh AA, Godoy G, Lerner SP, van de Rijn M, Shortliffe LD, Weissman IL, Chan KS. Three differentiation states risk-stratify bladder cancer into distinct subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2078–2083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrigan PM, Dobbin E, Freeburn RW, Wheadon H. Patterns of Wnt/Fzd/LRP gene expression during embryonic hematopoiesis. Stem cells and development. 2009;18:759–772. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujii N, You L, Xu Z, Uematsu K, Shan J, He B, Mikami I, Edmondson LR, Neale G, Zheng J, Guy RK, Jablons DM. An antagonist of dishevelled protein-protein interaction suppresses beta-catenin-dependent tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:573–579. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Juan J, Muraguchi T, Iezza G, Sears RC, McMahon M. Diminished WNT -> beta-catenin -> c-MYC signaling is a barrier for malignant progression of BRAFV600E–induced lung tumors. Genes & development. 2014;28:561–575. doi: 10.1101/gad.233627.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Fournier KF, Wang H, Marquis L, Abbruzzese JL, Gallick GE, Logsdon CD, McConkey DJ, Choi W. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition contributes to drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5820–5828. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Egeblad M, Rasch MG, Weaver VM. Dynamic interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Current opinion in cell biology. 2010;22:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Langhe SP, Sala FG, Del Moral PM, Fairbanks TJ, Yamada KM, Warburton D, Burns RC, Bellusci S. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) reveals that fibronectin is a major target of Wnt signaling in branching morphogenesis of the mouse embryonic lung. Dev Biol. 2005;277:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klotzsch E, Smith ML, Kubow KE, Muntwyler S, Little WC, Beyeler F, Gourdon D, Nelson BJ, Vogel V. Fibronectin forms the most extensible biological fibers displaying switchable force-exposed cryptic binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18267–18272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907518106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Mizuno K, Chen Q, Murakami M, Kimura M, Terada Y, Kano MR, Miyazono K, Uesaka M, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Accumulation of sub-100 nm polymeric micelles in poorly permeable tumours depends on size. Nature nanotechnology. 2011;6:815–823. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin SH, Kim WJ, Choi MJ, Park JM, Jin HR, Yin GN, Ryu JK, Suh JK. Aberrant expression of Wnt family contributes to the pathogenesis of diabetes-induced erectile dysfunction. Andrology. 2014;2:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeo EJ, Cassetta L, Qian BZ, Lewkowich I, Li JF, Stefater JA, 3rd, Smith AN, Wiechmann LS, Wang Y, Pollard JW, Lang RA. Myeloid WNT7b mediates the angiogenic switch and metastasis in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2962–2973. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stenman JM, Rajagopal J, Carroll TJ, Ishibashi M, McMahon J, McMahon AP. Canonical Wnt Signaling Regulates Organ-Specific Assembly and Differentiation of CNS Vasculature. Science. 2008;322:1247–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1164594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chauhan VP, Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD, Popovic Z, Chen O, Kamoun WS, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Normalization of tumour blood vessels improves the delivery of nanomedicines in a size-dependent manner. Nature nanotechnology. 2012;7:383–388. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]