Abstract

Recent advances in our understanding of how the intestinal microbiome contributes to health and disease have generated great interest in developing strategies for modulating the abundance of microbes and/or their activity to improve overall human health and prevent pathologies such as osteoporosis. Bone is an organ that the gut has long been known to regulate through absorption of calcium, the key bone mineral. However, it is clear that modulation of the gut and its microbiome can affect bone density and strength in a variety of animal models (zebra fish, rodents, chicken) and humans. This is demonstrated in studies ablating the microbiome through antibiotic treatment or using germ-free mouse conditions as well as in studies modulating the microbiome activity and composition through prebiotic and/or probiotic treatment. This review will discuss recent developments in this new and exciting area.

Keywords: bone density, prebiotics, probiotics, microbiome, osteoblast, osteoclast

Introduction

Recent advances in how microbial communities inhabiting the human body contribute to health and disease have generated great enthusiasm for the use of microbes to improve human health. Although microbes colonize most of the human body, the intestinal microbiota is by far the largest consortia associated with humans and has received the lion's share of attention in microbiome research. The association of altered microbial communities with diseases that are directly associated with the gut, such as obesity, diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disease, have been extensively studied in both animal models and human subjects. However, it has become increasingly clear that the intestinal microbiota plays important roles in the health of sites distant to the intestine including the skin, lungs, arteries, and bone.

Bone is an organ that the gut has long been known to regulate through absorption of the key bone mineral, calcium. An increasing number of studies suggest that there are additional ways to regulate bone health, including the microbiome. A number of research groups have studied the role of the microbiome and its effects on bone using a variety of approaches focusing on 1) direct alterations of the microbiota, 2) treatment with prebiotics to select for growth of certain bacteria in the GI tract and 3) treatment with probiotics to directly deliver beneficial bacteria to the GI tract. Here, we review these studies, focusing on how the gut environment can affect bone health.

1. Microbiome effects on bone

The gastrointestinal tract can be considered a tube of the “outside” running through the body that allows the organism to sample the environment and take in nutrients. In addition to food, the “outside” includes foreign cells and particles, such as bacteria, viruses and fungi, which enter the body and can take up occupancy in the gut microbiome. The intestinal microbiota play multiple, essential roles in human and animal health, and has thus been referred to as a forgotten organ (1,2). The microbiome of the gut, defined as the collective genetic material of the microbiota, contains an estimated 3-8 million unique genes, which expands the genetic capacity of humans by >100-fold (3,4). Although most work has focused on the colonic microbiota, all sections of the intestine are colonized with microbes with increasing density moving from the duodenum to the distal colon. The colon contains ~1012-1013 bacteria per gram of feces; it is clear we have many more bacteria populating our intestinal tract than we have cells in our body. Some of the activities provided by these communities include maturation and regulation of the immune system, digestion and release of essential dietary nutrients, support of intestinal barrier function, and the ability to suppress pathogen invasion. Moreover, microbes contribute to the production of an estimated 10-35% of metabolites detected in urine and feces (5,6). This further underscores the major impact of the microbiota in animal and human health.

Until recently, the role of the microbiota and therapeutic bacteria in bone physiology and health was largely ignored. Few studies have directly tested how bacterial populations impact bone, although some common themes have been proposed. Three main areas in which the microbiota is being investigated for its impact on bone are nutrient acquisition (calcium and phosphate), immune regulation, and direct effects through production of small molecules such as serotonin or estrogen-like molecules. While there are a few reports of individual bacteria (usually probiotics) impacting multiple aspects of bone physiology, we are far from understanding the complex interplay between the intestinal microbiota and bone health.

While studies demonstrating that probiotics and prebiotics can impact bone health have been published, the most direct evidence that the intestinal microbiota interacts with the host to modulate bone density came from a study comparing germ-free mice with animals that were conventionally housed under conditions promoting a typical intestinal community (denoted conventionally raised or CONV-R) (7). Germ-free mice had a 50% increase in their femur trabecular bone volume fraction and increased cortical bone when compared to CONV-R animals. Histomorphometry demonstrated that CONV-R animals had increased osteoclast numbers per area of bone compared to germ-free animals (7), suggesting increased bone catabolic activity in the presence of intestinal microbiota.

Previous work has demonstrated that inflammation in the bone marrow contributes to bone loss due to gut inflammation (8) and ovariectomy (OVX) (9,10). It has been hypothesized that increased levels of activated T-cells lead to enhanced expression of TNFα in the bone marrow. TNFα stimulates osteoclastogenesis, disrupting the normal balance of bone formation and resorption (11,12). Although the mechanism by which activated T-cells are increased in the bone marrow is not understood, a likely culprit for T-cell activation could be antigens presented by the intestinal microbiota (10). Consistent with the role of T-cells in bone physiology, CONV-R animals display increased levels of CD4+ T-cells, TNFα and osteoclast precursor cells (CD4 +/GR1−) compared to germ-free animals (7). Importantly, transferring a microbial community to germ-free female mice at 3 weeks of age led to decreased bone density, increased bone marrow CD4+ T-cells and increased osteoclast precursors (7), demonstrating a critical role for the microbiota in mediating bone physiology. While this study indicates an impact of intestinal microbes in bone physiology, other interesting questions were raised. First, these experiments were only performed in female animals; whether or not male mice would be similarly impacted is not known. Second, CONV-R mice had a higher mineral apposition rate than germ-free mice, suggesting that bone formation may be increased by gut microbiota in addition to increased osteoclast numbers. Third, phenotypic analysis of the bone was not performed (e.g. bone strength measurements) so that while germ-free animals have a higher bone density, other parameters may be abnormal in the absence of microbes.

Additional support for microbial regulation of bone health comes from three studies from Martin Blaser's group investigating the impact of antibiotics on bone during early mouse development. Brief exposure of weaning mice to sub-therapeutic concentrations of penicillin, vancomyin, or chlortetracycline resulted in a significant increase in bone mineral density after three weeks, although at seven weeks the control mice had caught up to and were similar to antibiotic treated animals (13). A similar impact on bone mineral density was also observed in a mouse model aimed at recreating therapeutic pediatric antibiotic exposure typically observed in children (14). Animals treated with tylosin, amoxicillin, or a mixture of both had larger bones and higher bone mineral content than controls. Interestingly, if animals were exposed to low levels of penicillin from birth it was found that sex specific effects on bone occurred (14). Male mice exposed to penicillin at weaning showed reduced bone mineral content and bone area compared to controls and this loss was further exacerbated by introduction of penicillin at birth. Female mice surprisingly showed improved bone mineral content and bone mineral density when exposed to penicillin (delivery of penicillin at weaning or birth made no difference). This study shows that antibiotics can have sex specific impacts on bone health. However, because these studies were longitudinal, the bones were analyzed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and therefore high-resolution analysis of trabecular and cortical bone were not performed. Nonetheless, these results are consistent with an altered intestinal microbiota.

2. Prebiotic effects on bone

Intestinal dysbiosis, defined as a shift in the microbial ecology of the gut to an unhealthy state, is linked with diseases and bone loss. While we are beginning to understand the changes in microbial composition associated with dysbiosis, the functional changes are far less understood. Bacteria express a variety of genes that can be modulated in response to changes in the environment. Many of these genes encode for enzymes involved in the production of metabolites such as short chain fatty acids (SCFA, ie: butyrate), branch chained fatty acids, bile acid derivatives, and vitamins. Generation of metabolic products by bacterial action is dependent on the substrate availability. These substrates are in part provided by prebiotics and therefore, prebiotics are critical components that can be used to modify the type of metabolites produced by the intestinal microbiota.

Prebiotics are non-digestible (by humans) fermentable food ingredients that promote both the growth of beneficial microorganisms in the intestine as well as promote health-benefiting changes in microbiome activity (ie: metabolites) (15). What constitutes a prebiotic is under debate and the definition may be expanded “metabolizable food ingredients” (instead of fermentable food ingredients) to incorporate a variety of bacteria-metabolized substrates besides carbohydrates, such as phenolic compounds (16). It is also possible that prebiotics could have direct immunologic or anti-pathogen effects on their own without metabolite production (16). Prebiotics encompass compounds found in a variety of foods such as chicory, garlic, leek, Jerusalem artichoke, dandelion greens, banana, onion, and bran that are readily available in grocery and health-food stores. In many cases, a significant amount of the food is needed to get enough prebiotic for activity, therefore prebiotics, such as inulin, have been developed into soft chew, capsule, tablet or shake forms and are manufactured by a variety of companies. Prebiotics include a large group of non-digestible oligosaccharides (NDOs) that contain typically 2-10 sugar subunits, but can have greater than 60 subunits (17). NDOs include a variety of structures: polydextrose, fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS, the first defined prebiotic in 1995), inulin (which contains FOS and is often extracted from chicory root), xylo-oligosaccharides (from xylan), galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS, produced from lactose) and soybean oligosaccharides (extracted from soybean whey). The microbiota can effectively breakdown most ingested prebiotics resulting in virtually no prebiotics in the stool (17). Prebiotics appear to be safe when given to healthy children and adults and don't have major side effects except that they can cause bloating, gas and increased bowel movements. In fact, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization supports the addition of prebiotics to infant (>5 months) formulas (18).

Over the past 20 years, many studies have identified a beneficial role of prebiotics in mineral metabolism, specifically enhancement of calcium absorption in both rodents and humans (17,19). For example, enhanced calcium absorption have been observed in healthy male rats treated with GOS or inulin (20,21), healthy female rats treated with polydextrose for 4-weeks (22) and healthy female mice treated for 6 weeks with agave fructose and inulin (23). Benefits can also be observed under pathologic conditions. For example, gastrectomized male rats treated with either FOS or difructose anhydride III (DFAIII, a nondigestable disaccharide) displayed increased calcium absorption (24,25). Estrogen deficiency is known to reduce calcium absorption and thus the role of prebiotics on ovariectomized rodents has been significantly studied. Both inulin and FOS increased calcium absorption in estrogen deficient ovariectomized (OVX) rats as determined by 45Ca tracer measurements (26). Similarly, DFAIII (15g/kg diet for 4 weeks) increased calcium absorption in ovariectomized (OVX) rats fed a normal diet, and remarkably in vitamin D deficient control and OVX rats (27). In humans, prebiotics such as FOS increase calcium absorption in adolescent boys and girls in a range of treatment times from 9 days (28), 3 weeks (29) to 1 year (30). In a double blind, placebo controlled cross-over study, six weeks of treatment with FOS increased calcium and magnesium absorption in postmenopausal women (average age 72 years old +/− 6.4 years) (31). While not all subjects responded to treatment, the ones with lower bone density (DEXA T-score of −1.7) absorbed more calcium and magnesium than subjects who had an average T-score of 0.2. GOS was also shown to modestly increase calcium absorption in postmenopausal women (32).

A key question is: does the increase in calcium absorption observed with prebiotic treatment translate into increased bone health, i.e., increased bone density and improved architecture? Under healthy control conditions, FOS and inulin increase trabecular and cortical thickness and bone calcium levels in mice (23) and increase bone mineral content, femoral bone volume and density in male rats (21,33). While there are variations in the effects of fibers, a study testing the role of eight different prebiotic fibers in weanling rats demonstrated that most (including: soluble corn fiber, soluble fiber dextrin, polydextrose, and inulin/FOS) had significant effects on bone density measures, with all trending to or significantly increasing cortical thickness, cortical bone mineral content and trabecular bone mineral density (34). Under estrogen deficient conditions, GOS, FOS and isoflavones prevented bone loss in OVX rats and mice, respectively (35,36). In gastrectomized rats, FOS prevented osteopenia (37). It should be noted that many prebiotic studies did not measure bone density and among those that did, several did not observe an effect (22,38). In addition to studies in rodents, prebiotics have been studied in other animals including chickens and pigs. In broiler chickens, inulin treatment increased bone mineralization/calcium content (39) while in pigs inulin did not impact bone health (40). In humans, effects of inulin on peak bone mass acquisition, menopausal bone loss and senile osteoporosis have been reviewed (41). As expected, short studies do not show changes in bone density, but a one year FOS treatment study was long enough to detect an increase in whole body bone mineral density in adolescent girls (30). Similarly, one year of FOS treatment reduced bone loss in post-menopausal women (42).

In addition to changes in bone architecture and mineralization, measures of actual bone strength are important. Prebiotics, such as FOS increased bone strength in several rodent studies including in OVX models (43). Similarly, GOS dose dependently increased rat tibia and femur strength (44,45). In addition, Anoecthochilus formosanus, a prebiotic herb, and inulin also increase bone strength in 12-week-old OVX rats (46). This effect on bone strength was observed in the absence of a significant change in bone volume, suggesting that prebiotics could change the extracellular matrix material properties.

Regarding effects of prebiotics on bone turnover, several studies indicate that prebiotics can affect osteoblast and/or osteoclast activity, with the response likely dependent upon the condition and prebiotic used. Some studies indicate bone formation is increased. For example, agave fructans and inulin increase serum osteocalcin levels in female mice 6 weeks after treatment (23). A GOS/FOS combination given with calcium increased bone mineralization and density, and more importantly, enhanced osteoblast surface (47). In contrast, inulin and FOS decreased the bone resorption-to-formation ratio in OVX rats (26). Similarly, 4-weeks of FOS or DFAIII decreased resorption markers in gastrectomized rats (25). Consistent with the latter rodent studies, a randomized intervention study in post-menopausal women (average age 61) demonstrated that 24 months of short-chained FOS treatment reduced serum and urine bone turnover markers (42).

Studies examining optimal prebiotic treatments for bone health have combined prebiotics with other bone benefiting compounds/activities. For example, FOS treatment (for 70 days) maximizes the effect of soy isoflavone treatment on BMD in OVX rats, making the lowest isoflavone dose of 10 ug/g/day effective. The combination also enhanced effects on bone strength at doses of 20ug/g/day and above. This effect appeared to result from a decrease in bone resorption rather than increased bone formation (43). Another study examined the effect of exercise with DFAIII treatment on bone health. The combination resulted in even greater increases in femoral calcium content, strength and total BMD (48). Taken together, some prebiotics are more effective than others and some combinations of prebiotics and/or functional foods display even greater effects than when given alone. Variations between studies may result from differences in dose, age, treatment length and/or rodent model strain and background and gender.

While many studies demonstrate prebiotics can benefit bone health, the exact mechanisms are not fully clear (38,41,49). Prebiotic enhancement of calcium absorption is at the heart of the majority of mechanisms, as this would supply mineral for bone formation. Models for how prebiotics could increase calcium absorption include the involvement of fermentation of the prebiotics to release SCFA. It has been demonstrated that many prebiotic fibers (i.e., soluble corn fiber or fiber dextrin, inulin, FOS, agave fructans) increase the cecal content of SCFA such as acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate and isovalerate (23,34,46). SCFA can affect calcium absorption via two mechanisms. First, SCFA can directly affect the epithelium to enhance calcium absorption. This can be measured as an increase in cecum weight and/or histologically by increased cecal villi structures that maximize surface area and absorption (50). There could also be increased paracellular calcium transport under these conditions and increased calcium binding protein expression (46,50). Secondly, production of SCFA increases acidity in the lumen of the cecum and colon. This is thought to occur by direct acidification by SCFA as well as by SCFA (butyrate) activation of H/Ca exchange. The lowered pH helps enhance mineral solubility making calcium more absorbable (50). For example, like most prebiotics, GOS dose dependently decreases cecal pH and increases cecal wall weight in rats (44,45). It should be noted however that there is no correlation between cecal SCFA levels and bone benefits (34). It is possible that SCFA levels in other regions of the gut, such as proximal or distal colon, may better correlate with bone benefits. Thus, the site of prebiotic effects/metabolites could also play a role in bone effectiveness. While a variety of SCFA are released in the cecum, studies show the potential for a different SCFA fingerprint in the colon. For example, treatment with agave fructans or inulin increases the levels of a variety of SCFA in the cecum but only acetate, propionate and butyrate levels in the colon (23). Similarly, DFAIII being shorter than FOS is thought to be more readily fermented in the proximal rather than distal colon whereas more complex long chain prebiotics take longer to digest and can still be detected in the distal large intestine (48).

Prebiotics can also alter the microbiome composition, which could affect SCFA production and alter bone health. Compounds such as FOS and GOS are known to increase the proportion of bifidobacteria in the gastrointestinal tract (44,45). Inulin and FOS have been demonstrated to change bacterial species numbers in both the proximal and distal gut, significantly increasing bifidobacteria, lactobacilli (proximal gut only) and eubacteria while decreasing clostridia in the distal gut (51). It is thought that stimulation of bifidobacteria levels leads to their increasing cleavage of isoflavone conjugates to yield their metabolites thereby increasing bioavailability of phytoestrogens (i.e., daidzein). A direct link between prebiotic induced changes in the gut microbiome and enhancement of bone density has yet to be found but is an area of active research.

3. Probiotic effects on bone

The word “probiotics” was initially coined as an antonym for “antibiotics”. Bacterial species now recognized as probiotics have been used since ancient times for use in cheese and for fermentation of products. Over the years, the definition of probiotics has been refined and is now defined as “live microorganisms that when administered in appropriate amounts can provide certain health benefits to the host” (52). Bacteria of the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Escherichia, Enterococcus and Bacillus have been used for their probiotic effects. In addition, yeast (Saccharomyces) has been used as a probiotic. Generally probiotics are provided as concentrated cultures in dairy products (eg. Yoghurt) or as inoculants in milk-based food or as dietary supplements in the form of powder, capsules or tablets. More recently they have been added to non-conventional products such as toothpaste, ice cream, and beer. How probiotics impact healthy and diseased animals and humans is an area of intense research and interest to the general public. Given that probiotics are readily available in grocery stores in the form of yoghurt and other food items that are part of everyday food intake, probiotics are being tested in various conditions, including bone health.

Some of the early studies examining the effectiveness of probiotics on bone health came from the poultry industry. Probiotics have been used in poultry for their beneficial effects on egg-shell quality and egg laying performance. For example, Abdelqader et al have shown that B. subtilis feeding improves egg performance and egg-shell quality in hens (53). In addition, probiotics have been studied in broiler chickens for improving performance and bone health. In one study, broiler chickens fed a low nonphytate phosphate diet were supplemented with active M. jalaludinii culture broth, which resulted in better performance in terms of nutrient availability and a significant increase in tibial mineral ash (54). In addition, probiotic supplementation (Bacillus licheniformis and Bacullus subtilis) of broilers significantly increased tibial thickness of lateral and medial walls and the tibiotarsal index (55). Another study tested the effect of Bacillus subtilis on ash and calcium content of the tibia in chicks in the presence and absence of Salmonella enteritidis infection (56). In this study, age of the chicks was found to be an important factor in influencing the positive effects of the probiotic or the negative effects of infection, with effects being more prominent in the young chicks. Thus overall, probiotics appear to have beneficial effects on growth and performance of hens, and broiler chickens.

In addition to their practical application in the poultry industry, probiotics have also been tested either as a treatment or adjuvant therapy to prevent periodontitis-induced bone loss. Oral administration of Bacillus subtilis reduced rat alveolar bone loss induced by ligature-induced periodontitis and also protected rats from small intestinal changes induced by periodontal inflammation(57). Stress was identified to influence the extent of the effect of probiotic therapy in periodontitis models (58), such that effects of the probiotic (B. subtilis) are less effective in the presence of stress. In another periodontal study, oral Saccharomyces cerevisiae was used as a monotherapy or combined as an adjuvant with standard therapy, and in both cases led to effective repair processes including less alveolar bone loss, decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL1β and increased anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (59). Topical application of Lactobacillus brevis CD2, by placing a lyopatch between the gingiva and buccal mucosa of the tooth ligated for induction of periodontitis, significantly prevented ligature-induced periodontal bone loss (60). In this study, expression levels of several pro-inflammatory mediator genes were markedly decreased in the probiotic treated group and evidence was provided to support that the anti-inflammatory effect was likely mediated through arginine deiminase, which is produced by the probiotic bacteria. Another study using rats, examined the effect of broccoli supplementation on high cholesterol diet-induced systemic and alveolar bone changes especially in the periodontal tissue (61). Importantly, they also included fermented broccoli, in which the broccoli was fermented with Bifidobacterium longum. The high cholesterol diet induced a significant increase in the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts but this was prevented in broccoli-supplemented group (both unfermented and fermented). The fermented group however had a greater decrease in the TRAP-positive osteoclasts suggesting that the B. longum mediated fermentation is able to induce a beneficial effect compared to unfermented broccoli. The effect of unfermented and fermented broccoli were linked to high serum antioxidant levels induced by the broccoli supplementation.

In one of the earlier studies looking at the role of probiotics in bone health in healthy mice, it was hypothesized that the anti-TNFα activity of L. reuteri ATCC PTA 6475 could help suppress TNF-mediated bone resorption. Interestingly, L. reuteri treatment was indeed able to improve bone health in healthy mice. This however, was selective in terms of gender: L. reuteri increased bone volume fraction, bone mineral density and bone mineral content only in the male mice but not the females (62). Effects in the male mice were not specific for a particular bone site; both femoral and vertebral bones showed increased bone density. Even though other studies have found gender-specific responses in different conditions, the specific effect of L. reuteri on bone parameters and its gender dependence was intriguing. Correspondingly, in the absence of estrogen (and possibly progesterone), L. reuteri treatment was able to increase bone density in female OVX mice, demonstrating the role of the sex hormones in shaping the response to the probiotic (63). These effects of probiotics on bone were also reproduced by another group (64), demonstrating that L. reuteri is a critical regulator of bone health under estrogen depleted conditions. Similar attenuation of bone loss was also observed with soy skim milk supplemented with L. paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU101 or L. plantarum NTU 102 in OVX mice (65). Narva et al have also shown similar results using milk fermented with Lactobacillus helveticus LBK-16H in rat OVX model. However, it should be noted that some of the bone parameters did not completely return to sham levels in the probiotic-fermented milk treated group (66). As discussed by the authors in this study, fermented milk used in the above two studies could lead to an increase in calcium absorption thereby enhancing bone health in the OVX rat model. However, work on L. reuteri in the OVX mouse model suggests that even in the absence of milk, probiotics are able to benefit bone health under low estrogen or estrogen-depleted conditions.

In addition to the benefits of probiotics in promoting bone health under estrogen depleted conditions, Zhang et al (67) recently demonstrated that, L. reuteri can reverse type 1-diabetes (T1D)-mediated bone loss and marrow adiposity in mice. Further analyses indicated that L. reuteri prevents diabetes and TNFα suppression of Wnt10b RNA levels in whole bone and osteoblasts in vitro, respectively (67). This is an intriguing finding because previous studies in menopause rodent models, where osteoclast activity is increased, suggested that L. reuteri can suppress osteoclast activity (63). Whereas in the T1D model bone loss is predominantly due to osteoblast dysfunction, yet L. reuteri is able to stimulate osteoblast activity under these conditions. These results suggest that L. reuteri is able to affect multiple mechanisms of bone remodeling under different pathophysiological conditions. Interestingly, probiotics have been found to be of benefit to bone health under in spontaneously hypertensive rats. This condition promotes bone loss, but supplementation of milk fermented with L. helveticus significantly increases bone mineral density and bone mineral content compared to water or skim milk or sour milk-treated rat groups (68). Although further mechanisms were not addressed, these results underscore the possible utility of probiotics in a wide range of “bone loss” pathologies.

Studies have also tried to examine if a combination of probiotics with prebiotics, also known as synbiotics, can benefit bone health better than one or the other. For example, a probiotic (Bifidobacterium longum) given with or without Yacon flour (a prebiotic) enhanced bone mineral content in rats, though strength was not significantly affected (69). Importantly, the effect of the prebiotic was markedly increased by the probiotic. However, it should be noted that the probiotic by itself provided significant benefit to bone mineral content even without the prebiotic.

Probiotics, by virtue of being microorganisms, have been studied for their effects in immune-modulated conditions. In this regard, they have generally been found to be of benefit in hyperinflammatory conditions. Enterococcus faecium is a probiotic that is similar to other lactic acid bacteria in that they can transiently colonize intestine in the humans and provide beneficial effects. One study examined this probiotic in the rat adjuvant-induced arthritis model (treated with methotrexate) which evokes a significant whole body decrease in bone mineral density (70). Interestingly, even though the probiotic by itself was not beneficial in the pathogenesis, in the presence of methotrexate, E. faecium treatment provided significant potentiation of the beneficial effect of the methotrexate treatment. Moreover, it also prevented whole body bone mineral density loss in the arthritic rats. Similar anti-inflammatory effects equivalent to indomethacin treatment (non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) has also been shown in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model in rats treated with Lactobacillus casei. Interestingly, while indomethacin suppressed all cytokines (pro and anti) broadly, L. casei inhibited pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6 and enhanced anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10(71). Probiotics also could be useful in conditions where there is compromised immune system. For example, malnutrition in mice alters B cell development in bone marrow and treatment of these mice with Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL 1505 reverses the negative effects of malnutrition thereby rendering the immune system to better fight against infection (72). In addition, under conditions of acute graft-versus host disease model, oral administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG before and after transplantation resulted in reduced disease as well as improved survival (73). Although further studies are obviously necessary to determine if probiotics are safe in immunocompromised patients, it is possible that probiotics are safe in a broad cohort of healthy and patient populations.

In addition to rodent models and poultry, effects of probiotics on bone health have also been tested in zebra fish models. Interestingly, addition of L. rhamnosus to normal zebrafish microflora leads to faster backbone calcification (74). This was associated with stimulation of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system by L. rhamnosus. It would be interesting to test if these effects on the IGF system are also observed in rodent and humans. In different studies, L. rhamnosus was shown to regulate genes involved in osteocyte formation via MAPK1/3 pathway in Zebra fish providing additional molecular mechanism (75).

Conclusions

There are many studies supporting a role for the gut and its microbiome in the regulation of bone density and health. Direct modulation of the quantity of bacteria present (through use of antibiotics, germ-free mice) as well as addition of bacterial substrates (prebiotics) and addition of beneficial bacteria (probiotics) can affect measures of bone health and calcium metabolism. However, there is still much to learn regarding our understanding of the signaling pathways that link the microbiome and gut to skeletal health. Future studies should be directed at identification of the mechanisms by which the microbiome regulates osteoblast and osteoclast activities as a means for developing future natural treatments for osteoporosis. We envision that modulation of the intestine-microbiome interaction to improve bone health will play an important role in human health and allow physicians to reduce the dependence on current pharmacological interventions for osteoporosis (which can have unwanted side effects).

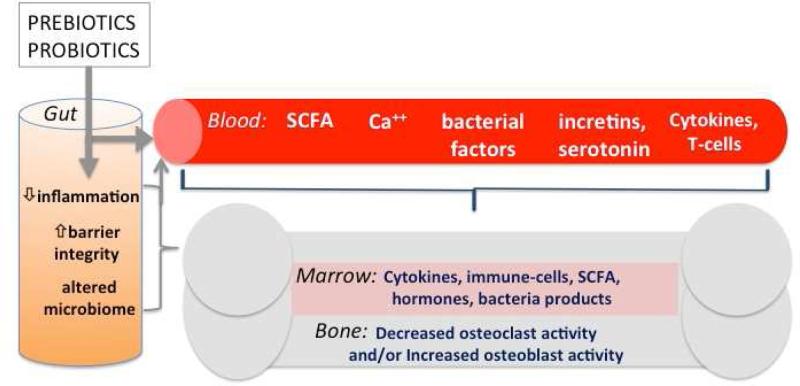

Figure 1. Model of gut microenvironment signals regulating bone density.

Prebiotics and probiotics can modulate the gut microbiome (composition and activity), increase barrier function and decrease intestinal inflammation, resulting in several local and systemic responses: 1) reduced inflammation in the gut, blood and bone; 2) increased metabolite levels such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) which can enhance calcium absorption and signal locally in the gut and in the bone; 3) increased bacterial secreted factors and intestinal hormones such as incretins and serotonin that are known to regulate bone density. Ultimately, the signals result in decreased osteoclast activity and/or increased osteoblast activity leading to enhanced bone density, structure and strength.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Dr. McCabe reports grants from Biogaia, during the conduct of the study; In addition, Dr. McCabe has a patent on the selection and use of lactic acid bacteria for bone health, United States Patent Application 20150150917 issued.

Dr. Britton reports grants from Biogaia, during the conduct of the study. In addition, Dr. Britton has a patent on selection and use of lactic acid bacteria for bone health (United States Patent Application 20150150917).

Dr. Parameswaran has nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article contains no studies with human or animal subjects performed by the author.

Contributor Information

Laura McCabe, Michigan State University, Department of Physiology, Department of Radiology, Biomedical Imaging Research Center, Biomedical Physical Science Building, 567 Wilson Road, East Lansing, MI 48824.

Robert A. Britton, Baylor College of Medicine, Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030, (713) 798-6189, Rob.Britton@bcm.edu.

Narayanan Parameswaran, Michigan State University, Department of Physiology, Biomedical Physical Science Building, 567 Wilson Road, East Lansing, MI 48824, (517) 884-5115, paramesw@msu.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Backhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, Sanders ME, Sartor RB, Sherman PM, Versalovic J, Young V, Finlay BB. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:688–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Human Microbiome Project C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu GD, Compher C, Chen EZ, Smith SA, Shah RD, Bittinger K, Chehoud C, Albenberg LG, Nessel L, Gilroy E, et al. Comparative metabolomics in vegans and omnivores reveal constraints on diet-dependent gut microbiota metabolite production. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng X, Xie G, Zhao A, Zhao L, Yao C, Chiu NH, Zhou Z, Bao Y, Jia W, Nicholson JK, et al. The footprints of gut microbial-mammalian co-metabolism. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:5512–5522. doi: 10.1021/pr2007945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Sjogren K, Engdahl C, Henning P, Lerner UH, Tremaroli V, Lagerquist MK, Backhed F, Ohlsson C. The gut microbiota regulates bone mass in mice. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27:1357–1367. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1588. [Directly measured the impact of intestinal microbes on bone health and associated parameters. Demonstrated the microbiome leads to lower bone volume fraction when compared to germ-free controls.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin R, Lee T, Young VB, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Colitis-induced Bone Loss is Gender Dependent and Associated with Increased Inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1586–1597. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318289e17b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Grassi F, Ryan MR, Terauchi M, Page K, Yang X, Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. IFN-gamma stimulates osteoclast formation and bone loss in vivo via antigen-driven T cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:122–132. doi: 10.1172/JCI30074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitzmann MN, Pacifici R. T cells: unexpected players in the bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency and in basal bone homeostasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:360–375. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi K, Takahashi N, Jimi E, Udagawa N, Takami M, Kotake S, Nakagawa N, Kinosaki M, Yamaguchi K, Shima N, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL-RANK interaction. J Exp Med. 2000;191:275–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kudo O, Fujikawa Y, Itonaga I, Sabokbar A, Torisu T, Athanasou NA. Proinflammatory cytokine (TNFalpha/IL-1alpha) induction of human osteoclast formation. J Pathol. 2002;198:220–227. doi: 10.1002/path.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methe BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell. 2014;158:705–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(Suppl 2):S1–63. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bindels LB, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Walter J. Towards a more comprehensive concept for prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:303–310. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Review article: prebiotics in the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:701–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas DW, Greer FR. Probiotics and prebiotics in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1217–1231. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholz-Ahrens KE, Ade P, Marten B, Weber P, Timm W, Acil Y, Gluer CC, Schrezenmeir J. Prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics affect mineral absorption, bone mineral content, and bone structure. J Nutr. 2007;137:838S–846S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.838S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chonan O, Watanuki M. Effect of galactooligosaccharides on calcium absorption in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1995;41:95–104. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.41.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberfroid MB, Cumps J, Devogelaer JP. Dietary chicory inulin increases whole-body bone mineral density in growing male rats. J Nutr. 2002;132:3599–3602. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legette LL, Lee W, Martin BR, Story JA, Campbell JK, Weaver CM. Prebiotics enhance magnesium absorption and inulin-based fibers exert chronic effects on calcium utilization in a postmenopausal rodent model. J Food Sci. 2012;77:H88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Vieyra MI, Del Real A, Lopez MG. Agave fructans: their effect on mineral absorption and bone mineral content. J Med Food. 2014;17:1247–1255. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohta A, Motohashi Y, Sakai K, Hirayama M, Adachi T, Sakuma K. Dietary fructooligosaccharides increase calcium absorption and levels of mucosal calbindin-D9k in the large intestine of gastrectomized rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1062–1068. doi: 10.1080/003655298750026769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiga K, Nishimukai M, Tomita F, Hara H. Ingestion of difructose anhydride III, a non-digestible disaccharide, improves postgastrectomy osteopenia in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1165–1173. doi: 10.1080/00365520600575753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zafar TA, Weaver CM, Zhao Y, Martin BR, Wastney ME. Nondigestible oligosaccharides increase calcium absorption and suppress bone resorption in ovariectomized rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:399–402. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitamura R, Hara H. Ingestion of difructose anhydride III partially restores calcium absorption impaired by vitamin D and estrogen deficiency in rats. Eur J Nutr. 2006;45:242–249. doi: 10.1007/s00394-006-0592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Heuvel EG, Muys T, van Dokkum W, Schaafsma G. Oligofructose stimulates calcium absorption in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:544–548. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin IJ, Davila PM, Abrams SA. Non-digestible oligosaccharides and calcium absorption in girls with adequate calcium intakes. Br J Nutr. 2002;87(Suppl 2):S187–191. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN/2002536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrams SA, Griffin IJ, Hawthorne KM, Liang L, Gunn SK, Darlington G, Ellis KJ. A combination of prebiotic short- and long-chain inulin-type fructans enhances calcium absorption and bone mineralization in young adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:471–476. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holloway L, Moynihan S, Abrams SA, Kent K, Hsu AR, Friedlander AL. Effects of oligofructose-enriched inulin on intestinal absorption of calcium and magnesium and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:365–372. doi: 10.1017/S000711450733674X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Heuvel EG, Schoterman MH, Muijs T. Transgalactooligosaccharides stimulate calcium absorption in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2000;130:2938–2942. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahara S, Morohashi T, Sano T, Ohta A, Yamada S, Sasa R. Fructooligosaccharide consumption enhances femoral bone volume and mineral concentrations in rats. J Nutr. 2000;130:1792–1795. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.7.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weaver CM, Martin BR, Story JA, Hutchinson I, Sanders L. Novel fibers increase bone calcium content and strength beyond efficiency of large intestine fermentation. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:8952–8957. doi: 10.1021/jf904086d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chonan O, Matsumoto K, Watanuki M. Effect of galactooligosaccharides on calcium absorption and preventing bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:236–239. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohta A, Uehara M, Sakai K, Takasaki M, Adlercreutz H, Morohashi T, Ishimi Y. A combination of dietary fructooligosaccharides and isoflavone conjugates increases femoral bone mineral density and equol production in ovariectomized mice. J Nutr. 2002;132:2048–2054. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.7.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohta A, Ohtsuki M, Uehara M, Hosono A, Hirayama M, Adachi T, Hara H. Dietary fructooligosaccharides prevent postgastrectomy anemia and osteopenia in rats. J Nutr. 1998;128:485–490. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholz-Ahrens KE, Schrezenmeir J. Inulin and oligofructose and mineral metabolism: the evidence from animal trials. J Nutr. 2007;137:2513S–2523S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2513S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortiz LT, Rodriguez ML, Alzueta C, Rebole A, Trevino J. Effect of inulin on growth performance, intestinal tract sizes, mineral retention and tibial bone mineralisation in broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. 2009;50:325–332. doi: 10.1080/00071660902806962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varley PF, McCarney C, Callan JJ, O'Doherty JV. Effect of dietary mineral level and inulin inclusion on phosphorus, calcium and nitrogen utilisation, intestinal microflora and bone development. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:2447–2454. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coxam V. Current data with inulin-type fructans and calcium, targeting bone health in adults. J Nutr. 2007;137:2527S–2533S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2527s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slevin MM, Allsopp PJ, Magee PJ, Bonham MP, Naughton VR, Strain JJ, Duffy ME, Wallace JM, Mc Sorley EM. Supplementation with calcium and short-chain fructo-oligosaccharides affects markers of bone turnover but not bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2014;144:297–304. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.188144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathey J, Puel C, Kati-Coulibaly S, Bennetau-Pelissero C, Davicco MJ, Lebecque P, Horcajada MN, Coxam V. Fructooligosaccharides maximize bone-sparing effects of soy isoflavone-enriched diet in the ovariectomized rat. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weaver CM, Martin BR, Nakatsu CH, Armstrong AP, Clavijo A, McCabe LD, McCabe GP, Duignan S, Schoterman MH, van den Heuvel EG. Galactooligosaccharides improve mineral absorption and bone properties in growing rats through gut fermentation. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2011;59:6501–6510. doi: 10.1021/jf2009777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45•.Weaver CM. Diet, gut microbiome, and bone health. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0257-0. [Nice review discussing the role of prebiotics and their enhancement of calcium absorption in animal and human studies.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang LC, Wu JB, Lu TJ, Lin WC. The prebiotic effect of Anoectochilus formosanus and its consequences on bone health. The British journal of nutrition. 2012:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryk G, Coronel MZ, Pellegrini G, Mandalunis P, Rio ME, de Portela ML, Zeni SN. Effect of a combination GOS/FOS prebiotic mixture and interaction with calcium intake on mineral absorption and bone parameters in growing rats. Eur J Nutr. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0768-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiga K, Hara H, Okano G, Ito M, Minami A, Tomita F. Ingestion of difructose anhydride III and voluntary running exercise independently increase femoral and tibial bone mineral density and bone strength with increasing calcium absorption in rats. J Nutr. 2003;133:4207–4211. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.12.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raschka L, Daniel H. Mechanisms underlying the effects of inulin-type fructans on calcium absorption in the large intestine of rats. Bone. 2005;37:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinidad TP, Wolever TM, Thompson LU. Effect of acetate and propionate on calcium absorption from the rectum and distal colon of humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:574–578. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langlands SJ, Hopkins MJ, Coleman N, Cummings JH. Prebiotic carbohydrates modify the mucosa associated microflora of the human large bowel. Gut. 2004;53:1610–1616. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.(FAO), F.a.A.O.o.t.U.N. Probiotics in food: Health and Nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. FAO Food and Nutrition paper. 2001;85 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdelqader A, Irshaid R, Al-Fataftah A-R. Effects of dietary probiotic inclusion on performance, eggshell quality, cecal microflora composition, and tibia traits of laying hens in the late phase of production. Tropical animal health and production. 2013;45:1017–1024. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan GQ, Abdullah N, Jalaludin S, Ho YW. Efficacy of supplementation of a phytase-producing bacterial culture on the performance and nutrient use of broiler chickens fed corn-soybean meal diets. Poultry science. 2002;81:1522–1532. doi: 10.1093/ps/81.10.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mutus R, Kocabagli N, Alp M, Acar N, Eren M, Gezen SS. The effect of dietary probiotic supplementation on tibial bone characteristics and strength in broilers. Poultry science. 2006;85:1621–1625. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.9.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadeghi AA. Bone Mineralization of Broiler Chicks Challenged with Salmonella enteritidis Fed Diet Containing Probiotic (Bacillus subtilis). Probiotics and antimicrobial proteins. 2014;6:136–140. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Messora MR, Oliveira LFF, Foureaux RC, Taba MJ, Zangeronimo MG, Furlaneto FAC, Pereira LJ. Probiotic therapy reduces periodontal tissue destruction and improves the intestinal morphology in rats with ligature-induced periodontitis. Journal of periodontology. 2013;84:1818–1826. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.120644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foureaux R.d.C., Messora MR, de Oliveira LFF, Napimoga MH, Pereira ANJ, Ferreira MS, Pereira LJ. Effects of probiotic therapy on metabolic and inflammatory parameters of rats with ligature-induced periodontitis associated with restraint stress. Journal of periodontology. 2014;85:975–983. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia VG, Knoll LR, Longo M, Novaes VCN, Assem NZ, Ervolino E, de Toledo BEC, Theodoro LH. Effect of the probiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae on ligature-induced periodontitis in rats. Journal of periodontal research. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jre.12274. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maekawa T, Hajishengallis G. Topical treatment with probiotic Lactobacillus brevis CD2 inhibits experimental periodontal inflammation and bone loss. Journal of periodontal research. 2014;49:785–791. doi: 10.1111/jre.12164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomofuji T, Ekuni D, Azuma T, Irie K, Endo Y, Yamamoto T, Ishikado A, Sato T, Harada K, Suido H, et al. Supplementation of broccoli or Bifidobacterium longum-fermented broccoli suppresses serum lipid peroxidation and osteoclast differentiation on alveolar bone surface in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. Nutr Res. 2012;32:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62•.McCabe LR, Irwin R, Schaefer L, Britton RA. Probiotic use decreases intestinal inflammation and increases bone density in healthy male but not female mice. Journal of cellular physiology. 2013;228:1793–1798. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24340. [Determined that responses to probiotics can be gender dependent. Demonstrated an increase in bone formation in male mice in response to L. reuteri treatment.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63••.Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, Schaefer L, Zhang J, Lee T, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Probiotic L. reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. Journal of cellular physiology. 2014;229:1822–1830. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24636. [Identified that use of probiotics can suppress osteoclast activity in ovariectomized mice and prevent bone loss. Demonstrated that probiotics can modify the intestinal microbiome in ovariectomized mice and secrete factors that suppress osteoclastogenesis in vitro.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohlsson C, Engdahl C, Fak F, Andersson A, Windahl SH, Farman HH, Moverare-Skrtic S, Islander U, Sjögren K. Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PloS one. 2014;9:e92368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiang SS, Pan TM. Antiosteoporotic effects of Lactobacillus - fermented soy skim milk on bone mineral density and the microstructure of femoral bone in ovariectomized mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:7734–7742. doi: 10.1021/jf2013716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Narva M, Rissanen J, Halleen J, Vapaatalo H, Vaananen K, Korpela R. Effects of bioactive peptide, valyl-prolyl-proline (VPP), and lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk containing VPP on bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Annals of nutrition & metabolism. 2007;51:65–74. doi: 10.1159/000100823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Zhang J, Motyl KJ, Irwin R, MacDougald OA, Britton RA, McCabe LR. Loss of bone and Wnt10b expression in male type 1 diabetic mice is blocked by the probiotic L. reuteri. Endocrinology. 2015:EN20151308. doi: 10.1210/EN.2015-1308. [Established that probiotics can block bone loss in a type 1 diabetes mouse model. A role for L. reuteri preventing TNF suppression of Wnt signaling in bone is suggested.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Narva M, Collin M, Lamberg-Allardt C, Karkkainen M, Poussa T, Vapaatalo H, Korpela R. Effects of long-term intervention with Lactobacillus helveticus-fermented milk on bone mineral density and bone mineral content in growing rats. Ann Nutr Metab. 2004;48:228–234. doi: 10.1159/000080455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rodrigues FC, Castro ASB, Rodrigues VC, Fernandes SA, Fontes EAF, de Oliveira TT, Martino HSD, de Luces Fortes Ferreira CL. Yacon flour and Bifidobacterium longum modulate bone health in rats. Journal of medicinal food. 2012;15:664–670. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rovensky J, Svik K, Matha V, Istok R, Ebringer L, Ferencik M, Stancikova M. The effects of Enterococcus faecium and selenium on methotrexate treatment in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2004;11:267–273. doi: 10.1080/17402520400001660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71••.Amdekar S, Singh V, Singh R, Sharma P, Keshav P, Kumar A. Lactobacillus casei reduces the inflammatory joint damage associated with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) by reducing the pro-inflammatory cytokines: Lactobacillus casei: COX-2 inhibitor. Journal of clinical immunology. 2011;31:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9457-7. [Showed a key difference between a broad anti-inflammatory which also suppresses the anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokine versus a probiotic that suppresses only pro-inflammatory cytokines but enhances IL-10.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salva S, Merino MC, Aguero G, Gruppi A, Alvarez S. Dietary supplementation with probiotics improves hematopoiesis in malnourished mice. PloS one. 2012;7:e31171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerbitz A, Schultz M, Wilke A, Linde H-J, Scholmerich J, Andreesen R, Holler E. Probiotic effects on experimental graft-versus-host disease: let them eat yogurt. Blood. 2004;103:4365–4367. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Avella MA, Place A, Du S-J, Williams E, Silvi S, Zohar Y, Carnevali O. Lactobacillus rhamnosus accelerates zebrafish backbone calcification and gonadal differentiation through effects on the GnRH and IGF systems. PloS one. 2012;7:e45572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maradonna F, Gioacchini G, Falcinelli S, Bertotto D, Radaelli G, Olivotto I, Carnevali O. Probiotic supplementation promotes calcification in Danio rerio larvae: a molecular study. PloS one. 2013;8:e83155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]