Abstract

Posttraumatic stress (PTSS) and generalized anxiety symptoms (GAS) may ensue following trauma. While they are now thought to represent different psychopathological entities, it is not clear whether both GAS and PTSS show a dose–response to trauma exposure. The current study aimed to address this gap in knowledge and to investigate the moderating role of subjects’ demographics in the exposure-outcome associations.

The sample included 249 civilian adults, assessed during the 2014 Israel–Gaza military conflict. The survey probed demographic information, trauma exposure, and symptoms. PTSS but not GAS was associated with exposure severity. Women were at higher risk for both PTSS and GAS than men. In addition, several demographic variables were only associated with PTSS levels. PTSS dose-response effect was moderated by education.

These findings are in line with emerging neurobiological and cognitive research, suggesting that although PTSS and GAS have shared risk factors they represent two different psychopathological entities. Clinical and theoretical implications are discussed.

Keywords: GAD, PTSD, Risk factors, Buffers, Demography, Violence

1. Introduction

The psychological impact of exposure to potentially traumatic stressors (PTS) including violence (Kilpatrick et al., 2003), natural disaster (Neria & Shultz, 2012), terrorism (Neria, Gross, & Marshall, 2006), and war, whether as military personnel (Dekel, Solomon, Ginzburg, & Neria, 2003) or civilians (Neria, Besser, Kiper, & Westphal, 2010), has been repeatedly demonstrated. The hazards of such exposure have included elevated cardiovascular disease (Steptoe & Kivimäki, 2012), immune reactions (Tsigos & Chrousos, 2002), and shortened lifespan (Neria & Koenen, 2003). Moreover, the heterogeneity of pathological response in the aftermath of stress is remarkable: not only do individuals respond with posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) (Besser, Weinberg, Zeigler-Hill, & Neria, 2014; Pfefferbaum et al., 1999) and fully diagnosable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Foa & Riggs, 1995; Johnson & Thompson, 2008), but they are also at elevated risk for other disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (Feerick & Snow, 2005; Ghafoori et al., 2009; Roemer, Molina, Litz, & Borkovec, 1996).

PTSD and GAD share several symptoms (APA, 2013) and risk factors (Famularo, Fenton, Kinscherff, & Augustyn, 1996; Fan, Zhang, Yang, Mo, & Liu, 2011). The two are, however, thought of as distinct diagnostic entities (APA, 2013), anchored in different psychosocial (Chen & Hong, 2010; Foa, Zinbarg, & Rothbaum, 1992; Grillon et al., 2009) and biological (Greenberg, Carlson, Cha, Hajcak, & Mujica-Parodi, 2013; Hettema, Prescott, Myers, Neale, & Kendler, 2005; Koenigs et al., 2008) factors. Both disorders have been documented in the aftermath of exposure to PTS (Ghafoori et al., 2009), however the question whether they similarly share dose-response relations with PTS remains unclear and has not been directly addressed. Symptoms of psychopathology may diverge some time after initial exposure to a PTS (Neria, Olfson, et al., 2010; Scheeringa, Zeanah, Myers, & Putnam, 2005) or appear immediately following the events (Besser & Neria, 2010; Besser et al., 2014; Besser, Zeigler-Hill, Weinberg, Pincus, & Neria, 2015). This withstanding, the association of severity of the PTS, which is difficult to accurately measure long after exposure, with both PTSS and GAS during or immediately after exposure, has seldom been gauged. This has left little information about the dose-response effects of such exposure on those outcomes (Johnson & Thompson, 2008). Unfortunately, the paucity of information regarding the immediate impact of such human suffering, the possible trajectories of symptomatic response, and the factors associated with this response, hinders the planning of effective, timely interventions.

Particularly, large-scale PTS that impacts a large number of individuals simultaneously (e.g. disasters, wars) requires a systemic response from well-informed clinicians and policy-makers. To allow for such a swift response, decision making may be based on the use of readily available information, such as demographic factors and exposure levels, as well as the relationships between them. This is important as not just exposure, as noted above, but demographic factors, especially gender, have been found to correlate with both GAS and PTSS in epidemiological studies as well as post-stressor studies (Daig, Herschbach, Lehmann, Knoll, & Decker, 2009; Dutton & Greene, 2010; Grant et al., 2009; Margruder et al., 2004). The salience of using such available information is underscored as, currently, more labor-intensive early indicators (e.g., diagnosis of acute stress disorder, biomarkers, assessment of self-efficacy) show only partial promise in predicting outcome (Bryant, 2007; Ritchie, Watson, & Friedman, 2007).

To address these gaps in knowledge, the current study aimed to utilize a unique real-time sample of Israeli civilians exposed to the threat of war, during the eruption of military conflict between Israel and Gaza during July and August of 2014. While previous studies with similar samples found significant psychological distress with varied consequences (Besser & Neria, 2009; Besser & Neria, 2012; Besser, Neria, & Haynes, 2009; Besser et al., 2014, 2015; Neria, Besser, et al., 2010), this study aimed to focus on PTSS and generalized anxiety symptoms (GAS) developing during the war, in order to address the following questions: (a) whether different PTSS and GAS are similarly associated with exposure severity; (b) to what degree PTSS and GAS are similarly related to demographic factors; and (c) which demographic factors moderate the associations of PTSS and GAS with trauma exposure. By exploring the nature of PTSS and GAS, their relations with trauma severity, and demographic factors during exposure to war trauma, we may expand highly needed knowledge regarding two major outcomes in the immediate aftermath of PTS.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

The data reported in this paper is derived from a larger project designed to study the immediate experiences of civilians and mental health consequences during the 2014 Israel–Gaza war, approved by the Sapir College Ethical Committee (Besser et al., 2015). Recruitment was conducted via online survey, employing social media networks. Participants were 249 Jewish Israeli civilians between the ages of 18 and 65 who, at the time of the survey, reported being under potential threat from rocket and missile fire from the Gaza Strip. Participants represented different geographic regions in Israel (58.6% in the south, and 41.4% in the center). Data collection spanned from July 8, 2014, and until the time of the first ceasefire declaration on August 5, 2014, thus including only time of active conflict.

2.2. Measures

Demographic information: Participants completed a survey providing demographic information, including gender, age, number of years of formal education, economic status, marital status, religiosity, place of birth, and employment. Their area of residence, which was used to assess time to shelter, a measure of exposure severity, was also assessed in the survey.

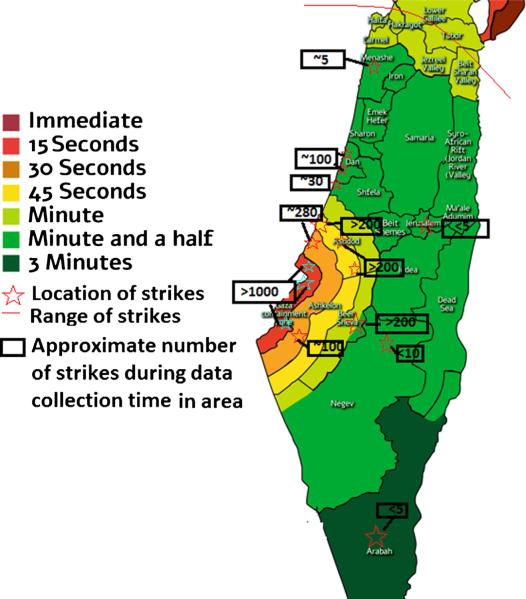

Time to shelter was used as a measure of trauma severity. Briefly, this is the time available for residents to take shelter between sirens going off and the impact of missiles, which varies depending on the distance from the Gaza Strip (see Fig. 1). The time to shelter ranged from approximately 15 s in the border areas to 90 s in the center of Israel. Alarm zones were defined by the Israeli Home Front Command. Three groups were defined based on time available to reach shelter (15, 30–45, or 60–90 s expected from beginning of siren to time of impact). Time to shelter was used as a measure of exposure for two reasons: First, areas closer to the Gaza strip, which had shorter time to shelter, were also more widely under intense fire than those farther away and with a longer time to shelter (see Fig. 1). Second, predictability and controllability play a major part in posttraumatic stress reactions (Foa et al., 1992), and longer time-frames to reach shelter may increase these. We therefore assumed that the shorter the time to shelter the higher the exposure.

Fig. 1.

Map of exposure by geographic location in Israel. Adapted from IDF Homefront Command website: http://www.oref.org.il/1096-en/Pakar.aspx using information from multiple media outlets (i.e., economist.com, haaretz.co.il, telegraph.co.uk).

PTSS

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C, Weathers & Ford, 1996). This 17-item self-administered questionnaire is based on DSM-IV (APA, 2000) criteria. Respondents rated the symptoms from the previous two weeks in reference to the current armed conflict using a 4-Point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The PCL-C Hebrew version has been widely used, evincing good psychometric properties (e.g., Besser et al., 2014, 2015; Neria, Besser, et al., 2010). Internal consistency coefficient for the PCL-C was 0.93 for the present sample. While DSM 5 (APA, 2013) had already been in use at the time, no validated Hebrew version of the corresponding PCL was available, thus the preexisting version was used. Total scores were used to approximate PTSS severity.

GAS

Symptoms were assessed using the GAD7, a subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). This tool includes seven questions measuring frequency of anxiety symptoms in the previous two weeks on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The current GAD7 Hebrew version, widely used, has shown good psychometric properties (Hobfoll et al., 2011). In this sample, internal consistency coefficient was 0.94. Total scores were used here to approximate GAS severity.

3. Data analytic strategy

First, in order to describe our sample, descriptive statistical analyses were conducted for the entire sample, providing background characteristics, as well as potential factors associated with symptomatology within the demographic variables. To this end, we used ANOVAs (for differences in means between independent categories the independent variables were Sex, Marital Status, Economic status, Religiosity, Employment, Place of birth, and the dependent variables for each ANOVA were total PCL and GAD scores) and correlations (for relationships between continuous variables: GAD and PCL total scores, and years of education and age).

Second, in order to test our dose-response hypothesis, we examined differences in symptom levels between exposure groups using ANOVA. We conducted two ANOVAs, with exposure as the independent variable. The dependent variables were total PCL score for the first analysis and total GAD score for the second.

Finally, in order to test for the potential moderating role of demographic variables in the association between time to shelter and psychopathology symptoms, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis in which PTSS, and then GAS, as the dependent variables, were regressed onto the independent variables: demographic variables in the first step, time to shelter in the second step, and their interactions in the third step. Variables were standardized prior to the computation of the product terms (interactions). We removed from the first step variables that did not reach .05 significance level in any of the above analyses and also removed from the final step those interactions that did not similarly reach significance.

We used contrast coding into dummy variables (+1 and −1) for categorical variables with two levels, and created two orthogonal contrast-coded linear polynomials for each categorical variable with three levels (time to shelter and marital status). Specifically, time to shelter was coded by the two following polynomials: contrast 1; 15 s [−2], 30–45 s [+1], 60–90 s [+1], and contrast 2; 15 s [0], 30–45 s [−1], 60–90 s [+1]. Marital status was coded by the two following polynomials: Contrast 1; single [−2], married [+1], separated/divorced/widowed [+1], and Contrast 2; single [0], married [+1], separated/divorced/widowed [−1]. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 22. Significance was set at .05 with all tests two-tailed.

4. Results

4.1. Univariate analysis

4.1.1. Sample characteristics and identification of symptom-associated factors

Of the 249 participants between ages 18 and 65 (M = 31.26, SD = 10.35), 80.1% were women, and 61.8% were not married. Participants had an average of 14.53 (SD = 2.88) years of formal education, with either employment or student status (96.4%), and 56.8% reported good to high economic status. Most (85.3%) participants were born in Israel, and 23.9% reported religiosity. Symptom levels were represented by a mean score of 36.13 for PTSS (SD = 14.43) and 6.66 for GAS (SD = 6.22).

Women endorsed higher symptom levels for both PTSS and GAS than did men (F[1,248] = 23.55, p < .001, d = .99 for GAS, and F[1,248] = 10.06, p < .001, d = .82 for PTSS). Individuals with higher economic status reported less symptoms than did their low-to-average counterparts (F[1,248] = 14.77, p < .001, d = .87 for PTSS, F[1,248] = 6.01, p = .02, d = .35 for GAS). Religiosity was associated with lower GAS (F[1,248] = 8.58, p < .001, d = .42), but not PTSS (F[1,248] = 2.63, p = .11). Employment was associated with lower GAS (F[1,248] = 5.90, p = .02, d = .53), and marginally lower PTSS (F[1,248] = 4.03, p = .05, d = .43). Age and number of years of formal education were both negatively associated with levels of both types of symptoms, with moderate correlations for PTSS (r = −.20, p < .001 for age, r = −.22, p < .001 for years of formal education) and weaker correlations for GAS (r = −.15, p = .02, for age, r = −14, p = .03, for years of formal education).

Marital status was significantly associated with PTSS (F[2,248] = 6.63, p < .001, d = .83), so that single individuals reported the highest, while separated, widowed and divorced individuals reported the lowest levels of symptoms (see Table 1). These differences, while carrying the same trend, were only marginal for GAS (F[2,248] = 3.12, p = .05, d = .47). Place of birth was not associated with PTSS (F[1,248] = 1.46, p = .23, d = .08), however those born in Israel had marginally higher GAS than their non-Israeli born counterparts (F[1,248] = 3.89, p = .05, d = .24).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and their relationship to symptom levels in war exposed civilians.

| PTSS |

GAS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Sex | Men | 30.44 | 10.96 | 3.96 | 3.86 |

| Women | 37.55 | 14.86 | 8.57 | 6.36 | |

| Marital status | Single | 38.52 | 14.53 | 8.35 | 6.22 |

| Married | 33.79 | 14.12 | 7.04 | 6.32 | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 25.27 | 5.53 | 4.18 | 3.34 | |

| Economic status | Low/average | 39.99 | 15.23 | 8.74 | 6.41 |

| Good/high | 33.12 | 13.06 | 6.81 | 5.96 | |

| Religiosity | Yes | 38.39 | 14.93 | 9.43 | 6.33 |

| No | 35.17 | 14.15 | 6.93 | 6.04 | |

| Employment | Yes | 35.78 | 14.41 | 7.48 | 6.15 |

| No | 45.56 | 12.41 | 12.56 | 6.46 | |

| Place of birth | Israel | 36.59 | 14.46 | 7.98 | 6.26 |

| Elsewhere | 33.49 | 14.19 | 5.81 | 5.72 | |

Note: PTSS, post-traumatic symptoms; GAS, generalized anxiety symptoms; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

4.1.2. Time to shelter and PTSS and GAS

In order to examine the association between time to shelter and levels of PTSS or GAS (i.e., dose–response effects) we examined between-group differences in PTSS and GAS (Table 2). Time to shelter was significantly associated with PTSS, so that shorter time to shelter was tied to higher levels of PTSS (F[3,248] = 7.09, p < .001, d = .93). Time to shelter was not significantly associated with GAS (F[3,248] = 2.07, p = .13, d = .45)

Table 2.

PTSS and GAS symptoms by time to shelter.

| Time to shelter (s) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 |

30-45 |

60-90 |

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| PSS | 41.69 | 15.29 | 39.47 | 15.20 | 33.55 | 13.35 |

| GAS | 8.58 | 5.71 | 8.73 | 6.79 | 7.03 | 6.06 |

Note: PTSS, post-traumatic symptoms; GAS, generalized anxiety symptoms; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

4.2. Multivariate analysis

4.2.1. Comprehensive models for predicting differential psychopathology and identification of moderators

At this stage, we examined possible moderation of dose-response effects by individual demographic differences (Time to shelter × demographic effects using hierarchical linear regression, see Tables 3 and 4). In the first step, we included only the variables found to be associated with symptoms in previous analyses and proceeded to examine time to shelter and interaction effects in the next steps. For PTSS, the individual variables which significantly associated with symptoms were education, gender, employment, and economic status (see Table 3). This model explained 15% of the variance in PTSS (F[7,241] = 6.28, p = .00). Marital status was marginally associated with PTSS, both for the comparison between single and other individuals (p = .05 for contrast 1, see Table 3, Model 1) and for the comparison between coupled and formerly coupled individuals (p = .06 for contrast 2, see Table 3, Model 1).

Table 3.

Regression model for moderation of time effects by demographic variables and time to shelter on PTSS.

| Model | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Constant) | 0.28 | 0.78 | |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.43 | |

| Education | –0.14 | –1.93 | 0.05 | |

| Sex | –0.18 | –3.00 | 0.00 | |

| Economic status | 0.18 | 2.92 | 0.00 | |

| Employment | –0.27 | –2.73 | 0.01 | |

| Marital status - contrast 1 | 0.17 | 1.98 | 0.05 | |

| Marital status - contrast 2 | –0.11 | –1.87 | 0.06 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 1.04 | 0.30 | |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.50 | |

| Education | –0.11 | –1.54 | 0.12 | |

| Sex | –0.17 | –2.87 | 0.00 | |

| Economic status | 0.16 | 2.50 | 0.01 | |

| Employed | –0.27 | –2.68 | 0.01 | |

| Marital status-contrast 1 | 0.17 | 2.02 | 0.04 | |

| Marital status-contrast 2 | –0.12 | –1.96 | 0.05 | |

| Time to shelter-contrast 1 | –0.07 | –1.16 | 0.25 | |

| Time to shelter - contrast 2 | –0.14 | –2.26 | 0.02 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | 0.49 | 0.62 | |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.67 | 0.50 | |

| Education | –0.44 | –3.04 | 0.00 | |

| Sex | –0.19 | –3.14 | 0.00 | |

| Economic status | 0.16 | 2.57 | 0.01 | |

| Employed | –0.25 | –2.38 | 0.02 | |

| Marital status - contrast 1 | 0.17 | 1.94 | 0.05 | |

| Marital status - contrast 2 | –0.12 | –2.12 | 0.03 | |

| Time to shelter - contrast 1 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.96 | |

| Time to shelter - contrast 2 | –0.13 | –2.22 | 0.03 | |

| Education × Time to shelter - contrast 1 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.55 | |

| Education × Time to shelter - contrast 2 | 0.33 | 2.37 | 0.02 |

Note: Marital status - contrast 1, single vs. coupled or formerly coupled; Marital status - contrast 2, currently coupled vs. formerly coupled; Time to Shelter - contrast 1, 15 s to shelter vs. more time; Time to shelter - contrast 2,30-45 s to shelter vs. 60-90 s.

Table 4.

Regression model for effects by demographic variables and time to shelter on GAS.

| Variables | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 0.06 | 0.95 | |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

| Education | –0.07 | –0.99 | 0.32 |

| Sex | –0.28 | –4.51 | 0.00 |

| Economic status | 0.10 | 1.54 | 0.12 |

| Marital status - contrast 1 | –0.19 | –1.86 | 0.06 |

| Marital status - contrast 2 | 0.14 | 1.64 | 0.10 |

| Employment | –0.12 | –2.06 | 0.04 |

| Place of birth | 0.07 | 1.19 | 0.23 |

| Religiosity | 0.10 | 1.68 | 0.10 |

Note: Marital status - contrast 1, single vs. coupled or formerly coupled; Marital status - contrast 2, currently coupled vs. formerly coupled.

Time to shelter, in itself, was also significantly associated with PTSS, and added to the explained variance in PTSS, above and beyond the demographic variables (R2 change = .03, F change[2,239] = 3.75, p = .03). The pattern emerging was consistent with a dose-response pattern, so that being at 60–90 s to shelter was associated with lower PTSS than being at 30–45 s to shelter (contrast 2, see in Table 3, Model 2). However, being at 15 s to shelter did not increase risk of symptoms than did having more time available (contrast 1, see Table 3, Model 2). With this addition of time to shelter in the second step, marital status became significantly associated with PTSS, with single individuals more symptomatic than their married or formerly married counterparts (contrast 1, see in Table 3, Model 2), however education was no longer significantly associated with PTSS.

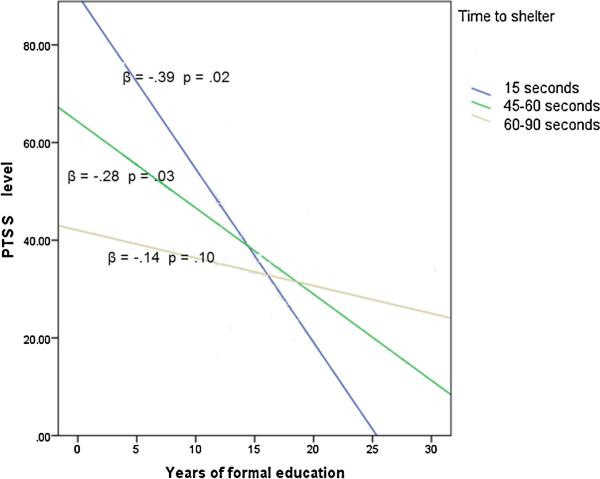

Finally, the interaction between time to shelter and education, when entered in the third step, significantly associated with symptoms (interaction with contrast 2, see in Table 3, Model 3), suggesting that education played a role in the relationship between symptoms and years of education for those with 30 s and over to reach shelter. This step significantly added to the explained variance within the model above and beyond the previously entered variables (R2 change = .02, F change[2,237] = 3.41, p = .02), suggesting moderation of time to shelter effects by education.

In order to further examine this interaction, PTSS were regressed on years of education by time to shelter groups. The dose-response effect for time to shelter appeared to be attenuated by education, with smaller slopes for this effect as one has accumulated more years of education (for the simple slope analysis see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PTSS by years of formal education for different time to shelter groups.

Note: PTSS, post-traumatic symptoms.

For GAS, only employment and gender survived as significantly associated with symptoms within a comprehensive model, with marital status marginally associating with GAS symptoms. Time to shelter did not significantly add to the model (R2 change = .01, F change[2,237] = 1.11, p = .33), therefore it and its interactions with previous variables were omitted from the final model (see Table 4).

5. Discussion

This study examined the presence of acute PTSS and GAS, and found that both were evident during exposure to war. In identifying risk factors for these symptoms, discernable differences in factors associated with GAS vs. PTSS emerged. These differences suggest different psychopathological entities, which may be accounted for by environmental, sociocultural, endocrine, genetic and structural factors.

Consistent with previous research (Neria, Nandi, & Galea, 2008), women were at higher risk for both types of symptoms than men, with large effects sizes, yet a dose-response effect of exposure severity was only observed in PTSS, underscoring the relevance of immediate exposure magnitude to the emergence of PTSS, but not GAS. Interestingly, those with the lowest time to shelter did not significantly differ in PTSS from the remaining sample. This may be explained by the relatively regular exposure of individuals in this area, which may lead to habituation, unlike their counterparts, for whom this exposure was the first in years. The dose-response effects were moderated by years of education, so that higher mean years of education associated with lower symptoms, and this association grew weaker as time to shelter grew longer. For GAS, only unemployment and being a woman were associated with higher symptomatology. However, effect sizes for unemployment were small.

The vulnerability of women to numerous psychiatric disorders, including PTSD and GAD, has been well documented (McLean, Asnaani, Litz, & Hofmann, 2011; Villamor & Saez de Adana, 2015). Differences in acceptability of emotional expression may lead to differences in reporting, and to the manifestation of internalizing symptoms among women but externalizing among men (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Women may tend to worry more, and also may be more prone to experience traumatic events, putting them at heightened risk for both disturbances (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Furthermore, emerging research suggests that endocrine differences may also contribute to the vulnerability of females, as sex hormones are associated with fear and anxiety, and anxiety levels tend to be higher in females during luteal phase and pregnancy (Carrion et al., 2002), times of high progesterone and low estrogen levels (Glover et al., 2012; Lebron-Milad, Graham, & Milad, 2012). Sex variability in cortisol has also been observed in PTSD: those diagnosed with the disorder have demonstrated higher diurnal cortisol levels than non-PTSDs, with females more so than males, both in childhood (Carrion et al., 2002) and adulthood (Laudenslager et al., 2009), but cortisol reactivity when facing PTS-related stressors has been demonstrated as higher among men (Dekel, Ein-dor, Gordon, Rosen, & Bonanno, 2013). Inconsistency in measurement of cortisol (e.g., diurnal vs. baseline vs. reactivity, plasma vs. saliva, etc.) may account for variability in sex-related findings (Olff, Langeland, Draijer, & Gersons, 2007). Cortisol itself may have an effect on fear learning, with different patterns for males and females (Jovanovic et al., 2011; Van Ast, Vervliet, & Kindt, 2012). Thus, it would seem that both biological propensities and social constructions maintain this gender disparity.

The relationship between marital status and PTSS in this study, which eveinced large effect sizes, is also in line with existing literature, which underscores the role social support and secure attachment play as possible buffers (Besser & Neria, 2012; Besser et al., 2009; DeKeyser Ganz, Raz, Gothelf, Yaniv, & Buchval, 2010; Karstoft, Armour, Elklit, & Solomon, 2013). Factors such as employment (Found here to associate with PTSS and GAS) and economic status (Found here to associate with PTSS with large effect size), may have direct influence on access to resources, which in turn may impact the breadth of choices available to the individual. As uncontrollability of events has been repeatedly associated with both PTSD and a propensity toward anxiety in general (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Foa et al., 1992), this may explain the association of these factors with psychopathology.

Education may provide tools with which to understand the situation, plan contingencies, and critically evaluate available information, which can be unreliable (Akbari & Som, 2014; Montoya et al., 2013). The interaction found between exposure severity and education in association with PTSS suggests the latter may provide a buffer against experiencing the events as stressful and uncontrollable, thus mitigating the dose-response effect.

The differential dose–response effects found here between PTSS and GAS may be consistent with previous studies demonstrating similar findings in children, wherein pediatric anxiety was not associated with stress exposure, while PTSD was, and both were associated with demographic factors pertaining to social status, education, and age (Fan et al., 2011). Among adults, conflicting findings have emerged, supporting dose-response effects for both phenomenologies (Graça Pereira, Figueiredo, & Fincham, 2012).

When examining these findings as a whole, both the elevated risk for psychopathology in this sample and the context-specificity of PTSS, but not GAS, are particularly apparent. This bolsters the view of posttraumatic stress as distinct from anxiety disorders in its unique, reactive nature (APA, 2013). The question remains, what vulnerabilities are at the crux of this stress sensitivity which begets PTSD? The answer to this question may reside within biomarker studies.

Previous research suggests that GAD shares genetic factors with other disorders, including panic disorder and PTSD, with 38% additive common genetic contribution to likelihood of GAD symptoms. However, for PTSD only 21% of the genetic variance was explained by common factors and 14% was accounted for by unique factors (Chantarujikapong et al., 2001). Thus, PTSD seems to have a unique genetic basis. Furthermore, emerging knowledge from neuroimaging research further aids in understanding distinct mechanisms of PTSD and anxiety (Etkin & Schatzberg, 2011). For example, hyperresponsivity in fear circuitry regions including the amygdala (Koenigs et al., 2008; Schienle, Ebner, & Schäfer, 2011; Schneier, Kent, Star, & Hirsch, 2009; Shin et al., 2004; Yehuda & LeDoux, 2007) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; Blair et al., 2012; Hayes, Vanelzakker, & Shin, 2012; Hopper, Frewen, van der Kolk, & Lanius, 2007) has been reported in both PTSD and anxiety disorders including GAD. On the other hand, areas involved in fear inhibition have exhibited different activation patterns in PTSD and other anxiety disorders. For GAD and panic disorder alike, lower activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) was associated with anxiety severity and functional impairment (Ball, Ramsawh, Campbell-Sills, Paulus, & Stein, 2013) whereas PTSD participants exhibited increased dlPFC activation in the face of threatening stimulus (Fani, Jovanovic, Ely, & Bradley, 2012) and decreased deactivation when facing a non-threatening stimulus (Morey et al., 2009) compared to non-PTSD counterparts. Moreover, greater activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) in response to threat vs. non-threat cues has been observed in GAD, with degree of activation inversely correlated with anxiety (Monk, Nelson, & McClure, 2006), whereas participants with PTSD have exhibited decreased activation in vmPFC (Koenigs et al., 2008) as well as lower gray matter volume in this area (Keding & Herringa, 2015). Thus, it may be that, while individuals with GAD can be overly reactive to threat, they attempt to compensate and regulate this threat, albeit ineffectively. For individuals with PTSD, the mechanisms allowing for regulation may be impaired, as safety cues may not trigger fear inhibition.

Taken together, these studies suggest a unique vulnerability for people with PTSD, where fear circuitry, once triggered, may be difficult to shut down. This may explain the importance of exposure severity, as greater exposure may be associated with facilitated fear activation to subsequent cues. This also stresses the importance of identifying factors able to buffer this effect, possibly attenuating the initial categorization of threat and nipping the activation process in the bud. For the development of anxiety disorders, the impairment in regulation seems less severe, and is susceptible to moderators such as intolerance of uncertainty (Chen & Hong, 2010), which may be less contingent on exposure severity.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations and future directions

Our study has several limitations: the sample is not random and may not be representative of the population in this area. Few men participated, perhaps due to the mandatory draft, which made many men unavailable at this time (Besser et al., 2014, 2015). Also, the use of internet for data collection may have led to the inadvertent exclusion of specific populations with limited internet access. Additionally, the use of an online survey does not allow for diagnostic assessment, and, while all participants were exposed to a potentially traumatic stressor, their subjective experience of it was not taken into account (e.g., whether their response involved “intense fear, helplessness, or horror”, as specified in criterion A2 of the DSM IV). Our measure of exposure, while presenting a feasible measure for use in the field, similarly does not take into account the subjective experience or the individual number of “under fire” experiences. Finally, as a cross sectional investigation, we are limited by lack of knowledge of participant history, such as prior symptoms. Thus, we do not know whether these symptoms preceded the PTS, but also cannot account for previous psychopathology as a possible risk factor for the current symptoms (Edmondson et al., 2012). However, this method of sampling uniquely allows a real-time glimpse into the immediate experience of civilians under threat, without exacerbating the threat by requiring travel in this precarious time.

In the future, it would be useful to follow up on this sample and examine lingering symptoms: the immediate symptoms may constitute an adaptive reaction to a state of danger and not necessarily indicate burgeoning psychopathology (Bryant et al., 2015; Karstoft et al., 2013). Information on how likely participants are to have a clinically diagnosable disorder several months later would be beneficial in identifying not only risk, but resilience factors, and trajectories of natural recovery. Also, it would be useful to replicate these analyses in additional exposed populations, such as the Palestinians of Gaza, and war- and violence-exposed communities worldwide, in order to examine the generalizability of these results. Finally, the possible explanations offered here for basic, mechanistic differences between PTSD and GAD and their etiology should be empirically tested.

6.2. Clinical implications

When considering the allocation of real-time resources in times of disaster and war, this type of investigation has the potential to inform policy by using readily available information. The current results underscore the importance of reaching out to vulnerable populations as soon as possible during these times: women, those who are more exposed, those who are unemployed, and those who are economically disadvantaged. Particularly, bolstering education (e.g., investing drop-out reduction within the public school system, offering scholarships to higher education, and providing opportunities for adult education) in conflict-ridden areas emerges as a public health issue, due to its potential to mitigate the effects of ongoing PTS. In addition, some of the effects found, such as those of marital status (which remain marginal here, with all other variables accounted for) may be mediated through variables beyond the scope of this investigation, such as social support and attachment (Besser & Neria, 2009, 2010, 2012; Besser et al., 2009) and these factors should also be considered when planning interventions. In summary, when facing a large-scale PTS, swift interventions targeting vulnerable populations may be in order, but preventative strategies geared at bolstering possible buffers, put in place by policy makers, should be considered preemptively.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Helpman is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 5T32MH096724-03.

References

- Akbari K, Som R. Evaluating the quality of internet information for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2014;24(11):2003–2006. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1403-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1403-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ball TM, Ramsawh HJ, Campbell-Sills L, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Prefrontal dysfunction during emotion regulation in generalized anxiety and panic disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43(7):1475–1486. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712002383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y. PTSD symptoms, satisfaction with life, and prejudicial attitudes toward the adversary among Israeli civilians exposed to ongoing missile attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(4):268–275. doi: 10.1002/jts.20420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y. The effects of insecure attachment orientations and perceived social support on posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms among civilians exposed to the 2009 Israel–Gaza war: A follow-up Cross-Lagged panel design study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44(3):335–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y. When home isn't a safe haven: Insecure attachment orientations, perceived social support, and PTSD symptoms among Israeli evacuees under missile threat. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4(1):34–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0017835. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y, Haynes M. Adult attachment, perceived stress, and PTSD among civilians exposed to ongoing terrorist attacks in Southern Israel. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47(8):851–857. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.003. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Weinberg M, Zeigler-Hill V, Neria Y. Acute symptoms of posttraumatic stress and dissociative experiences among female israeli civilians exposed to war: The roles of intrapersonal and interpersonal sources of resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jclp.22083. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22083. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Besser A, Zeigler-Hill V, Weinberg M, Pincus AL, Neria Y. Intrapersonal resilience moderates the association between exposure-severity and PTSD symptoms among civilians exposed to the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict. Self and Identity. 2015;141:1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.966143. [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Geraci M, Smith BW, Hollon N, DeVido J, Otero M, et al. Reduced dorsal anterior cingulate cortical activity during emotional regulation and top-down attentional control in generalized social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and comorbid generalized social phobia/generalized anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(6):476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA. Early intervention for post-traumatic stress disorder. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2007;1(1):19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00006.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Nickerson A, Creamer M, O'Donnell M, Forbes D, Galatzer-Levy I, et al. Trajectory of post-traumatic stress following traumatic injury: 6-year follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2015:417–423. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.145516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.145516. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carrion VG, Weems CF, Ray RD, Glaser B, Hessl D, Reiss AL. Diurnal salivary cortisol in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(7):575–582. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantarujikapong SI, Scherrer JF, Xian H, Eisen S. a, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, et al. A twin study of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, panic disorder symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder in men. Psychiatry Research. 2001;103(2-3):133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00285-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Hong RY. Intolerance of uncertainty moderates the relation between negative life events and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49(1):49–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.006. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daig I, Herschbach P, Lehmann A, Knoll N, Decker O. Gender and age differences in domain-specific life satisfaction and the impact of depressive and anxiety symptoms: A general population survey from Germany. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(6):669–678. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9481-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, Solomon Z, Ginzburg K, Neria Y. Combat exposure, wartime performance, and long-term adjustment among combatants. Military Psychology. 2003;15(2):117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dekel S, Ein-dor T, Gordon KM, Rosen JB, Bonanno GA. Cortisol and PTSD symptoms among male and female high-exposure 9/11 survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:621–625. doi: 10.1002/jts.21839. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKeyser Ganz F, Raz H, Gothelf D, Yaniv I, Buchval I. Post-traumatic stress disorder in Israeli survivors of childhood cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37(2):160–167. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.160-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/10.ONF.160-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Greene R. Resilience and crime victimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(2):215–222. doi: 10.1002/jts.20510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D, Richardson S, Falzon L, Davidson KW, Mills MA, Neria Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: A meta-analytic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038915. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Schatzberg A. Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):968–978. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff R, Augustyn M. Psychiatric comorbidity in childhood post traumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(10):953–961. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00084-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(96)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Mo L, Liu X. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among adolescents following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(1):44–53. doi: 10.1002/jts.20599. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani N, Jovanovic T, Ely T, Bradley B. Neural correlates of attention bias to threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychology. 2012;90(2):134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.001.Neural. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feerick MM, Snow KL. The relationships between childhood sexual abuse, social anxiety, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(6):409–419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-7802-z. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS. Posttraumatic stress disorder following assault: Theoretical considerations and empirical findings. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4(2):61–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10771786. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Zinbarg R, Rothbaum BO. Uncontrollability and unpredictability in post-traumatic stress disorder: An animal model. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(2):218–238. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoori B, Neria Y, Gameroff MJ, Olfson M, Lantigua R, Shea S, et al. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder symptoms in the wake of terrorist attacks: A study in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(3):218–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.20419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover EM, Jovanovic T, Mercer KB, Kerley K, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, et al. Estrogen levels are associated with extinction deficits in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graça Pereira M, Figueiredo AP, Fincham FD. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and quality of life in colorectal cancer after different treatments: A study with Portuguese patients and their partners. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2012;16(3):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson D. a, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg T, Carlson JM, Cha J, Hajcak G, Mujica-Parodi LR. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex reactivity is altered in generalized anxiety disorder during fear generalization. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(3):242–250. doi: 10.1002/da.22016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Pine DS, Lissek S, Rabin S, Bonne O, Vythilingam M. Increased anxiety during anticipation of unpredictable aversive stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder but not in generalized anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JP, Vanelzakker MB, Shin LM. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2012 Oct; doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00089. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2012.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Myers JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for anxiety disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):182–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti D, Hall BJ, Brom D, Palmieri PA, Johnson RJ, et al. Are community studies of psychological trauma's impact accurate? A study among Jews and Palestinians. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(3):599–605. doi: 10.1037/a0022817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper JW, Frewen PA, van der Kolk BA, Lanius RA. Neural correlates of reexperiencing, avoidance, and dissociation in PTSD: Symptom dimensions and emotion dysregulation in responses to script-driven trauma imagery. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(5):713–725. doi: 10.1002/jts.20284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson H, Thompson A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(1):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Phifer JE, Sicking K, Weiss T, Norrholm SD, Bradley B, et al. Cortisol suppression by dexamethasone reduces exaggerated fear responses in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(10):1540–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karstoft K-I, Armour C, Elklit A, Solomon Z. Long-term trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: The role of social resources. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):1163–1168. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08428. http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13.m08482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keding TJ, Herringa RJ. Abnormal structure of fear circuitry in pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(September):537–545. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Huey ED, Raymont V, Cheon B, Solomon J, Wassermann EM, et al. Focal brain damage protects against post-traumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11(2):232–237. doi: 10.1038/nn2032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudenslager ML, Noonan C, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Buchwald D, Bremner JD, et al. Salivary cortisol among American Indians with and without posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Gender and alcohol influences. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23(5):658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebron-Milad K, Graham BM, Milad MR. Low estradiol levels: A vulnerability factor for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72(1):6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Johnson MR, Vaughan J. a, Carson TC, et al. PTSD symptoms, demographic characteristics, and functional status among veterans treated in VA primary care clinics. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(4):293–301. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038477.47249.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(6):496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45(8):1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Nelneyson E, McClure E. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1091–1097. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, Hernández S, Massana MP, Herreros O, Garcia-Giral M, Cardo E, et al. Evaluating internet information on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment: Parent and expert perspectives. Education for Health (Abingdon, England) 2013;26(1):48–53. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.112801. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.112801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RA, Dolcos F, Petty CM, Cooper DA, Hayes JP, LaBar KS, et al. The role of trauma-related distractors on neural systems for working memory and emotion processing in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43(8):809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.10.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires. 2008.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Besser A, Kiper D, Westphal M. A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder in israeli civilians exposed to war trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(3):322–330. doi: 10.1002/jts.20522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Gross R, Marshall R. Mental health in the wake of terrorism: Making sense of mass casualty trauma. In: Neria Y, Gross R, Marshall R, editors. Mental health in the wake of terrorist attacks. Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 1–11. 9/11 http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511544132.003. [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Koenen KC. Do combat stress reaction and posttraumatic stress disorder relate to physical health and adverse health practices? An 18-year follow-up of Israeli war veterans. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2003;16(2):227–239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1061580021000069407. [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(4):467–480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Digrande L, Wickramaratne P, Gross R, et al. Long-term course of probable PTSD after the 9/11 attacks: A study in urban primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(4):474–482. doi: 10.1002/jts.20544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Shultz JM. Mental health effects of hurricane sandy: Characteristics, potential aftermath, and response. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(24):2571–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.110700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.110700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BPR. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(2):183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tucker PM, Tivis RD, Moore VL, Gurwitch RH, et al. Posttraumatic stress responses in bereaved children after the Oklahoma city bombing. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(11):1372–1379. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199911000-00011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie EC, Watson PJ, Friedman MJ, editors. Interventions following mass violence and disasters: Strategies for mental health practice. Guilford Press; 2007. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=vDBPEBFGnlgC&pgis=1. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Molina S, Litz BT, Borkovec TD. Preliminary investigation of the role of previous exposure to potentially traumatizing events in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 1996;4:134–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:3<134::AID-DA6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Myers L, Putnam FW. Predictive validity in a prospective follow-up of PTSD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):899–906. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000169013.81536.71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000169013.81536.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A, Ebner F, Schäfer A. Localized gray matter volume abnormalities in generalized anxiety disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2011;261(4):303–307. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0147-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00406-010-0147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Kent JM, Star A, Hirsch J. Neural circuitry of submissive behavior in social anxiety disorder: A preliminary study of response to direct eye gaze. Psychiatry Research. 2009;173(3):248–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM, Orr SP, Carson MA, Rauch SL, Macklin ML, Lasko NB, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex during traumatic imagery in male and female Vietnam veterans with PTSD. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(2):168–176. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 2012;9(6):360–370. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):865–871. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ast VA, Vervliet B, Kindt M. Contextual control over expression of fear is affected by cortisol. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012 Oct; doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00067. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Villamor A, Saez de Adana E. Gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder. In: Sáenz-Herrero M, editor. Psychopathology in women. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2015. pp. 587–609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05870-225. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ford J. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S, PCL-M, PCL-PR). In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Sidran Press; Lutherville, MD: 1996. pp. 250–251. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, LeDoux J. Response variation following trauma: A translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron. 2007;56(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]