Abstract

Mixed-solvent molecular dynamics (MixMD) simulations use full protein flexibility and competition between water and small organic probes to achieve accurate hot-spot mapping on protein surfaces. In this study, we improved MixMD using HIV-1 protease as the test case. We used three probe-water solutions (acetonitrile-water, isopropanol-water, and pyrimidine-water), first at 50% w/w concentration and later at 5% v/v. Paradoxically, better mapping was achieved by using fewer probes; 5% simulations gave a superior signal-to-noise ratio and far fewer spurious hot spots than 50% MixMD. Furthermore, very intense and well-defined probe occupancies were observed in the catalytic site and potential allosteric sites that have been confirmed experimentally. The Eye site, an allosteric site underneath the flap of HIV-1 protease, has been confirmed by the presence of a 5-nitroindole fragment in a crystal structure. MixMD also mapped two additional hot spots: the Exo site (between the Gly16-Gly17 and Cys67-Gly68 loops) and the Face site (between Glu21-Ala22 and Val84-Ile85 loops). The Exo site was observed to overlap with crystallographic additives such as acetate and DMSO that are present in different crystal forms of the protein. Analysis of crystal structures of HIV-1 protease in different symmetry groups has shown that some surface sites are common interfaces for crystal contacts, which means they are surfaces that are relatively easy to desolvate and complement with organic molecules. MixMD should identify these sites; in fact, their occupancy values help establish a solid cut-off where “druggable” sites are required to have higher occupancies than the crystal-packing faces.

INTRODUCTION

A crucial step in structure-based drug design (SBDD) is the identification of the potential sites on the target protein for high-affinity ligand binding. Binding sites are generally characterized by binding hot spots on the protein surface that have high propensity for ligand binding,1–4 typically lined by solvent-exposed, hydrophobic amino acid residues. Such composition allows organic molecules with hydrophobic characteristics to effectively compete against the bulk solvent (~ 55.5 Molar of water) for the binding hot spots through a combination of enthalpic and entropic contributions, where loosely bound water molecules on the hydrophobic protein surface can be displaced with minimal energy penalty.

Two experimental approaches were developed to identify binding hot spots: the multiple-solvent crystal structure (MSCS) method5–9 and fragment binding detected by nuclear magnetic resonance (“SAR by NMR”).10,11 Both methods use small organic molecules with weak binding as probes to identify the hot spots. These experimental methods are very powerful, but there are limitations that prevent wide application across all targets. NMR is limited to small proteins, and some targets are not amenable to crystallization. Furthermore, for the proteins that form good crystals, the integrity of the crystal may deteriorate with the addition of organic solvent. When this happens, it reduces the precision of the crystal model and results in larger B-factors and higher uncertainties. To circumvent these restrictions, computational methods that utilize static crystal structures to locate binding hot spots have been developed.12–17 These methods have had varying degrees of success and share common limitations. In particular, numerous local free energy minima are common on the probed surface due to the lack of protein dynamics in the crystal structure. Another major shortfall is the lack of solvation effect and the probe-water competition at the protein surface.

To enhance the identification of binding hot spots, methods that sample probe-protein interactions dynamically have been developed.18–24 These methods perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the target protein solvated with probe-water solution and identify the binding hot spots that are frequented by probes. The MacKerell group has developed the site-identification by ligand competitive saturation (SILCS) method that simulates the targets in a benzene/propane/water mixture to generate maps of binding hot spots,19,20,22 where binding free energy is estimated from the binding propensities of the probes.18,25 However, SILCS requires the use of artificial repulsive interactions to avoid aggregation of the highly hydrophobic probes. Seco et al.23 simulated proteins in an isopropanol/water solution box and estimated the binding affinity by the ratio of observed probe density to the expected probe density. Bakan et al.18 assessed the druggability of the protein surface by estimating the probe binding affinities of a mixture of organic solvents in water. The choice of solvent probes and their proportion in the mixture were based on the frequency of the chemical feature in drug molecules.26 However, this approach relies on the estimation of probe density and has not been validated by comparison to MSCS or “SAR by NMR”, the experimental counterparts to these probing methods.

As an alternative to these MD methods, we developed our method for mixed-solvent molecular dynamics (MixMD).27–29 MixMD uses miscible, organic solvents as probes for hot-spot identification, which avoids the introduction of artificial repulsion terms to prevent the aggregation of the probes. The positions of the probes are integrated into probe-occupancy maps that can be examined in a manner similar to electron density maps. The accuracy of MixMD has been confirmed27 by direct comparison of the MixMD result for hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) in 50% w/w acetonitrile (ACN)-water solution and HEWL results from MSCS9 and “SAR by NMR”.10 In a follow-up work,28 ACN and isopropanol (IPA) were used as probes for several monomeric proteins: HEWL, elastase, p53, RNase A, subtilisin, and thermolysin. MixMD correctly reproduced the binding hot spots seen in the MSCS of these test cases.

In this work, we use four probe types – ACN, IPA, pyrimidine (1P3), and N-methylacetamide (NMA) – and demonstrate that on the timescale examined here, 50% MixMD method does not disrupt the integrity of HIV-1 protease (HIVp), a homodimeric protein held together by non-covalent interactions. Furthermore, we demonstrate the advantages of utilizing 5% v/v probe-water solution over 50% w/w solution in MixMD. A 5% concentration of probes in water was examined because it is compatible with conditions used in experimental verification by NMR and crystallography; these lower concentrations are usually not detrimental to the stability of the protein or crystal integrity.19,30 Serendipitously, lowering the probe concentration significantly improved the signal-to-noise ratio of genuine binding hot spots over spurious ones. We also examined the hot spots on the protein surface that are part of protein-protein interfaces or crystal contacts. These results confirm the usefulness of MixMD as a strategy to map binding cavities and protein-protein interfaces, which can then guide the construction of pharmacophore models for ligand screening.

METHODS

Setup of MixMD

The crystal structures of HIVp with semi-open (PDB: 1HHP31) and closed conformations (PDB: 1PRO32) were used in the simulations. All bound ligands were removed. The tLeAP module of AMBER1133 was used to add hydrogens to the protein with (one of the two catalytic ASP was protonated to ASH), and the protein was parameterized with FF99SB force field.34 SHAKE35 was applied to restrain all bonds to hydrogen atoms and 2-fs simulation time step was used. Particle Mesh Ewald36 and a 10-Å cutoff distance for long-range interaction were used. The system charge was neutralized with Cl− counter ions, and temperature was regulated through an Andersen thermostat.37

Amber parameters for ACN and NMA were used.38 Parameters for IPA and 1P3 were based on the OPLS-AA parameters.39,40 These choices were based on an in-depth exploration of available probe parameters.29 For 50% w/w probe-water MixMD, the protein was solvated in an 18-Å, pre-equilibrated box of probe and TIP3P water.41 For 5% probe-water MixMD, a v/v definition was needed because of the setup protocol. The solvent around the protein was made in a layered manner, in which the protein was coated with a shell of probe solvent which was then placed within a large box of water. Control of probe concentration was achieved through adjusting the volume of the water box to obtain the correct ratio of probe and water molecules. Ratios of water molecules to probe molecules are given in the Supplementary Material for all solvents at both 50% w/w and 5% v/v.

The MixMD system underwent 250 cycles of steepest-descent minimization followed by 4750 cycles of conjugate-gradient minimization with the protein fixed. Each system was gradually heated from 10 K to 300 K over 80 ps in the NVT ensemble while the protein was restrained by a harmonic force constant of 10 kcal/mol Å2. Restraints on protein heavy atoms were gradually removed over 350 ps while the temperature was maintained at 300 K, followed by unrestrained equilibration for 1.4 ns. For each system, five independent, 20-ns production runs of MixMD were performed in the NPT ensemble using the GPU-enabled PMEMD.33,42 Proper mixing of the probes and water was monitored with radial distribution functions (RDF), which we have shown is necessary to verify solvent parameters and setup protocol.29 The RDF are given in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Material.

Essential Dynamics

Essential dynamics (ED)43,44 was used to monitor and compare the dynamics of the protein structure in MixMD simulations. PTRAJ performed the matrix calculation on the protein backbone heavy atoms and generated the eigenvectors and the associated eigenvalues of the MD trajectories.45 Vectors of each residue were superimposed onto the Cα atom of the residue and the results were visualized using VMD in the form of a porcupine plot.46,47 Dot product was used to quantitatively compare two eigenvectors, in which the vector on each of the n number of Cα atoms in an eigenvector was compared to the corresponding vector in another eigenvector. The medians of the dot-products describe the global similarity of the compared eigenvectors.

Probe Occupancy Maps

The last 10 ns of each of the individual runs were combined and analyzed by PTRAJ to generate the probe occupancy map. The trajectory was fitted to the reference structure (i.e., crystal structure 1HHP) by Cα RMSD, excluding the flexible flap region of residues 45–55 and 45’-55’. The PTRAJ “grid” command, with a 0.5 Å x 0.5 Å x 0.5 Å spacing over the entire volume, was used to calculate the occupancies of water and probe at each grid point. To effectively compare the occupancy maps from different sources, the maps were normalized by converting the raw data into standard score (Z-score) with the equation

where xi is the occupancy at a grid point i, µ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of occupancy of all grid points, respectively. The normalized probe occupancy maps were visualized with PyMOL.48 The contour levels of probe occupancy represent the number of standard deviation (σ) between the raw occupancy at the grid points and the mean occupancy, similar to viewing electron density maps.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

We have chosen HIVp as a test case because it is a system with interesting dynamic properties that has been studied extensively.49,50 A prominent feature of HIVp is a pair of flexible β-hairpin flaps51–54 that have different organization between “closed” and “semi-open” conformations. These flaps control the access to the peptide-binding site. All HIV drugs bind to the closed state, and their features occupy well known subsites that recognize its peptide substrates. However, there are three allosteric sites being pursued. In the closed conformation, the “Eye” site is occupied with each tip of the flaps docked into to the flap-tip recognition pocket on its dimeric partner. The Eye site becomes open and available when the flaps open to other conformations. Our previous work in Damm et al.55 pioneered the Eye site as a novel allosteric site of HIVp and developed an Eye site pharmacophore model that helped identify a novel molecule targeting this site.56 Importantly, the Eye site has been confirmed by crystallography of apo HIVp in semi-open conformation,57 in which a resolved fragment 5-nitroindole (5NI) occurred in the Eye site. In addition, the Exo site, a cleft formed by the elbow/cantilever/fulcrum components of the protease, has been confirmed by crystallography.57 Finally, crystallographic observation57 and protein denaturation experiments58 indicate the presence of the Flap site on the solvent-exposed side of the flap; we observed that site albeit weaker than the other hot spots observed. Together these finding show the usefulness and accuracy of the MixMD method.

MixMD with Semi-Open HIVp in a High Concentration of Probe Solvent

In our first MixMD simulations of apo, semi-open HIVp in 50% probe-water, the protein was solvated in a box of pre-mixed solution (Table S1). To confirm the solutions remained well mixed throughout the MixMD simulations, the RDFs of the probes and water were calculated for both the first and second 10-ns interval. Both the early and late RDFs of all three 50% probe-water MixMD did indeed converge to unity between 8–10Å, reproducing the appropriate patterns we have shown previously.29 This pattern indicates that even mixing was maintained throughout the simulations and no aggregation of probe and water molecules occurred.

There was concern that unrestrained MixMD simulations of a protein without structure-stabilizing disulfide bridges may be susceptible to denaturation with the introduction of so many small organic probes.19 Global and local structure analyses of the protein were performed to verify that the probes did not destabilize the protein. Cα RMSDs were calculated for the core of HIVp (excluding the flaps), which remained stable throughout the MixMD simulations (Figure S2). The core RMSD of 50% ACN-water, IPA-water, and 1P3-water MixMD simulations were 1.7 ± 0.3 Å, 1.6 ± 0.3 Å, and 1.8 ± 0.7 Å, respectively, which is similar to that of our 40-ns, pure-water MD simulation of apo HIVp (1.5 ± 0.3 Å). Two of the 1P3-water MixMD simulations experienced flap opening event,34 hence the slightly larger core RMSD (Figure S2). At the local level, the flaps of HIVp maintained the handedness in semi-open conformation. Flap-openness was measured by the Asp25-Ile50 Cα distance, and the values were ACN-water (19.2 ± 3.9 Å), IPA-water (14.7 ± 2.0 Å), and 1P3-water (16.1 ± 2.7 Å). Flap openness in the MixMD simulations was similar to that of HIVp in a pure-water MD (15.2 ± 3.8 Å). These values are closer to the openness observed in the crystal structure of the semi-open conformation (~17.2 Å in PDB:1HHP) than to the openness in closed conformation (~12.6 Å in PDB:1PRO).

In addition to the average conformational behavior above, we wanted to examine how the solvent influenced the dynamic behavior. We applied ED to extract the collective atomic displacements that may be important to protein functions,43,44 and the resultant eigenvectors were compared to the ED of apo HIVp from a 40-ns, pure-water MD. We used a global similarity factor, which is equivalent to the median of the dot-products of two eigenvectors, to quantitatively describe the degree of overlap between the compared ED eigenvectors. Through comparison, we observed that the first several eigenvectors of all MixMD systems had good correlation (global similarity factor > 0.5) to the corresponding eigenvectors of apo HIVp in pure-water MD (Table 1, Figure S3). Furthermore, these eigenvectors often encompassed the most significant dynamic motions of the protein44 that described the opening-closing and shearing motions of the flaps; the cumulative eigenvalue of the first 3 modes of ED usually describes > 70% of the simulated protein motions (Table S2). Hence, ED comparison suggests that the application of 50% probe-water solution in MixMD did not introduce and artificial effect in the general protein dynamics of HIVp.

Table 1.

Global similarity factor of ED eigenvectors from HIV-1p in pure-water MD and 50% w/w MixMD

| Pure-Water MD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% w/w MixMD |

1st – 1st | 2nd – 2nd | 3rd – 3rd | 4th – 4th | 5th – 5th |

| ACN-water | 0.734 | 0.516 | 0.605 | 0.353 | 0.487 |

| IPA-water | 0.556 | 0.786 | 0.557 | 0.518 | 0.111 |

| 1P3-water | 0.760 | 0.180 | 0.600 | 0.053 | 0.056 |

Identification of Binding Hot Spots in the Semi-Open State

MixMD uses organic probes to identify hot spots that have high propensity for ligand binding, and the frequency of probe occupation should be proportional to its binding affinity. To identify the hot spots, the probe positions throughout the MixMD trajectory were integrated into a probe-occupancy map, which is then normalized for quantitative comparison of different probe-occupancy maps. The intensity of the occupancy is represented as the number of standard deviation (σ) above the basal level of occupancy. Hence, the intensity of the probe occupancy can be visualized as a surface of contour that represents the minimum σ value of probe occupancy within the enclosed volume, just like visualizing electron density from Xray crystallography. To focus on the hot spots that are most frequently sampled by the probes, the contour level is adjusted so that only the probe occupancies with strong intensity would remain. Higher σ values equal higher occupancies by probe solvent.

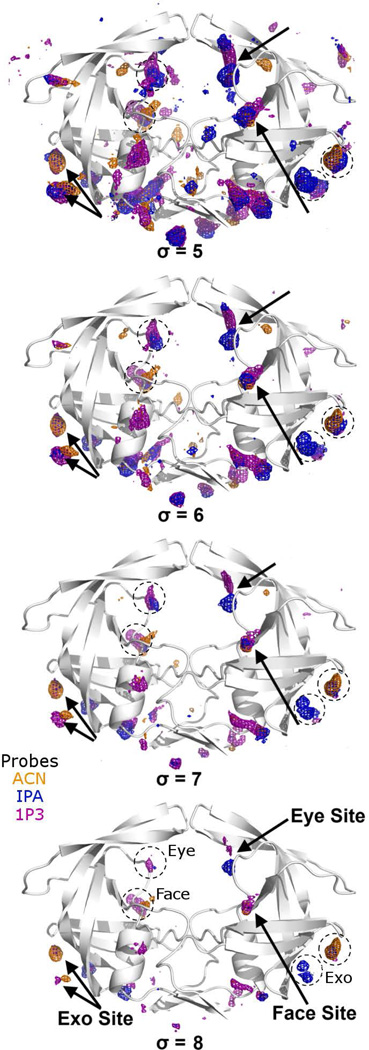

In the MixMD simulations of semi-open, apo HIVp in 50% ACN-water, IPA-water, and 1P3-water solutions, we observed numerous weak probe occupancies that disappeared as the contour level was increased from σ = 5 to 8. Among the intense probe occupancies that remained, several patches of protein surface were consistently mapped by all three organic probes, and these volumes occupy the Exo, the Eye, and the Face sites (Figure 1). In order to map the central active site, we had to use the closed form of HIVp, which is discussed farther below.

Figure 1.

Probe occupancies of 50% probe-water MixMD of semi-open HIVp. ACN, IPA, and 1P3 probe occupancies are shown as orange, blue, and purple meshes, respectively. The probe occupancy of MixMD is normalized and the intensity of the occupancy is quantified by the standard deviation value (σ) above the basal level of occupancy. This σ value is shown as the occupancy contour level. Increasing the contour level from σ = 5 to 8 eliminates weak occupancies. All three probes have consistent overlapping occupancies in the Exo, Eye, and Face sites. HIVp is C2-symmetric, and the matching sites on the other monomer are noted with dashed circles.

Using a High Probe Concentration Yields Many Weak Occupancies

Regardless the probe type in the 50% probe-water MixMD, at low contour levels like σ = 5, there are numerous tiny probe occupancies on the protein surface (Figure 1), similar to results observed in other methods.20,22–25,59,60 Although many of these weak occupancies are irrelevant and can be eliminated simply by increasing the contour level to σ = 8, they may misguide and distract researchers from studying the genuine binding hot spots. Such “noise,” or spurious probe occupancies, may result from the use of excessive quantity of probe in the MixMD; excess probe molecules may occupy the local free energy minima on the protein surface because other probe molecules have already occupied the genuine binding hot spots. Another drawback of the 50% probe-water MixMD is the narrow gap that differentiates intense and weak probe occupancies; increasing the contour level by as few as 3 σ units effectively eliminated most of the probe occupancies. This narrow gap for the signal-to-noise ratio (real sites seen with 8-σ contour vs the additional “noise” sites with a 5-σ contour) hinders the distinction between the intense occupancies of genuine hot spots from the weak, spurious occupancies.

MixMD of Semi-Open, Apo HIVp with Low Concentrations of Probe Solvent

Large concentrations of pure solvent were used as a way to increase the sampling across the protein surface. However, one of the pitfalls of using the 50% probe-water MixMD is that the concentration of organic solvent is too high to be directly compared to experimental data. This kind of solvent is not experimentally feasible because many proteins are known to be sensitive to additives in the buffer, e.g., salts, buffering agents, and organic solvents. For example, proteolytic activity of HIVp diminishes when DMSO concentration exceeds 5%.61

To circumvent the issues arising from using high concentrations of probes in MixMD simulations, we reduced the probe concentration to 5% in the MixMD. A low concentration was chosen because experiments are limited to low concentrations, and this will facilitate comparisons to experimental data. Since the probe molecules would be very dilute in the 5% probe-water MixMD (~200 probe molecules to ~15,000 water molecules), we were concerned that the probe molecules may spend too much time in the vast volume of the bulk solvent and have limited sampling of the protein surface. Hence, we altered the solvation strategy by layering the solvent around the protein: a shell of probe molecules was first coated on the protein and then the protein and probes were placed into a large box of water molecules that created a probe-to-water ratio of 1:55.5 (Table S3). The diffusion constants of all the probes are high enough that the water molecules can compete off the weakly bound probes within the short equilibration phase. Probe solvent in the binding hot spots interacts strongly and remains there for an extended period of time to yield high occupancies on the grid maps. This layered approach is a different way to enhance sampling of the probe solvent on the protein surface, and it is inspired by the “washing” steps in MSCS.

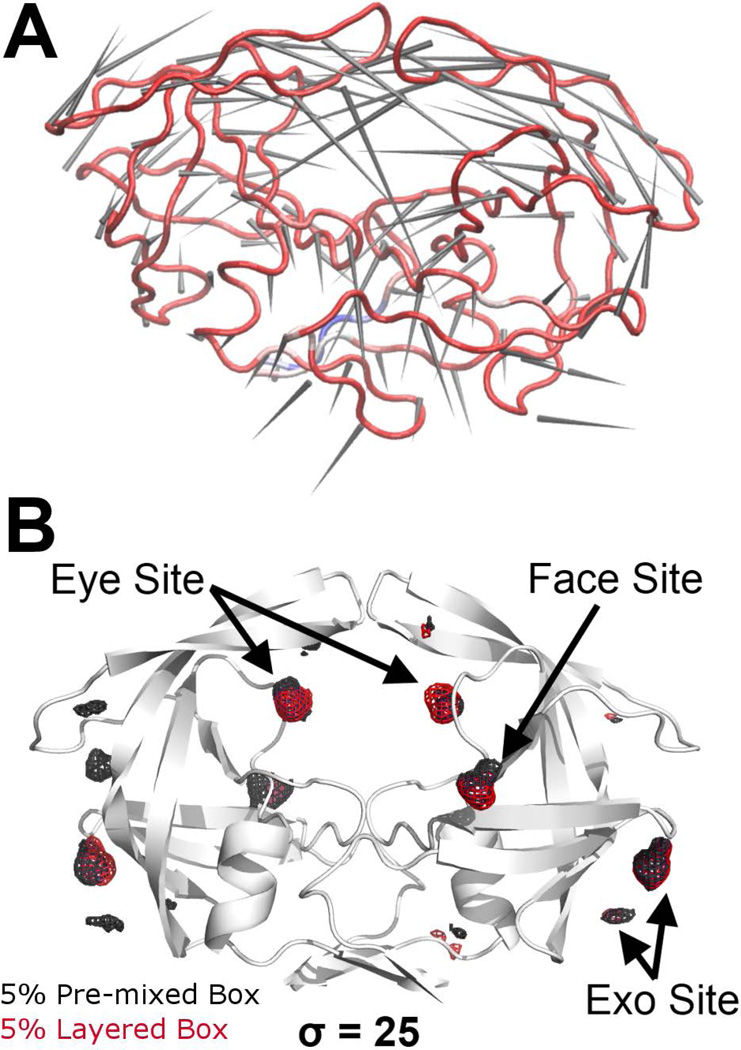

To confirm that performing MixMD with the layered solvation method did not introduce artifacts to probe distribution and protein motion, we performed both pre-mixed and layered MixMD of HIVp with 5% ACN-water solution for comparison. Identical to the other MixMD simulations, the solvent RDFs of the layered MixMD converged to unity by the completion of equilibrations and remained well mixed for the duration of all production runs. Thus, the artifice of the layered-solvation strategy appears minimal and suitable for use in MixMD. We performed ED analysis on the protein from the pre-mixed and the layered MixMD and found that the two sets of protein dynamics are highly correlated. The global similarity factors of the 1st eigenvector of the pre-mixed and layered MixMD have high values (> 0.7), demonstrating that the protein dynamics were highly similar in both pre-mixed and layered MixMD (Table 2, Figure 2A where red is used to show correlated motion). Most importantly, the hotspots identified by MixMD with 5% ACN-water were essentially identical for pre-mixed and layered solvation strategies, and they were in good agreement with the 50% simulations. At contour σ = 25, both strategies identified the Exo, Eye, and Face sites as the most occupied regions on the protein surface. Furthermore, the number of weak occupancies are significantly reduced (Figure 2B compared to Figure 1), providing a much cleaner probe occupancy map.

Table 2.

Global similarity factors of the first five ED eigenvectors of 5% v/v ACN-water MixMD and pure-water MD simulations of HIV-1p

| Eigenvector – Eigenvector |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-mixed – Water | 1 – 1 | 1 – 2 | 2 – 3 | 3 – 2 | 4 – 4 |

| 0.721 | 0.702 | 0.744 | 0.726 | 0.744 | |

| Layered – Water | 1 – 1 | 1 – 2 | 2 – 1 | 2 – 4 | 3 – 5 |

| 0.789 | 0.748 | 0.633 | 0.681 | 0.704 | |

| Layered – Mixed | 1 – 1 | 1 – 3 | 3 – 2 | 4 – 3 | 5 – 2 |

| 0.971 | 0.683 | 0.710 | 0.853 | 0.619 | |

Figure 2.

Comparison of pre-mixed and layered MixMD of HIVp in 5% ACN-water solution. (A) Porcupine plot of the dot-product of the 1st ED eigenvectors of pre-mixed and layered MixMD. Red indicates a high degree of correlation, and blue indicates anti-correlation. The arrow shows the net vector of motion at the residue. The compared ED eigenvectors are highly correlated with a global similarity factor of 0.971. (B) At high occupancy contour level (σ = 25), only the Exo, Eye, and Face sites are identified in the ACN probe occupancy map. No significant difference is observed between the pre-mixed MixMD probe occupancy (black mesh) and that of the layered MixMD (red mesh).

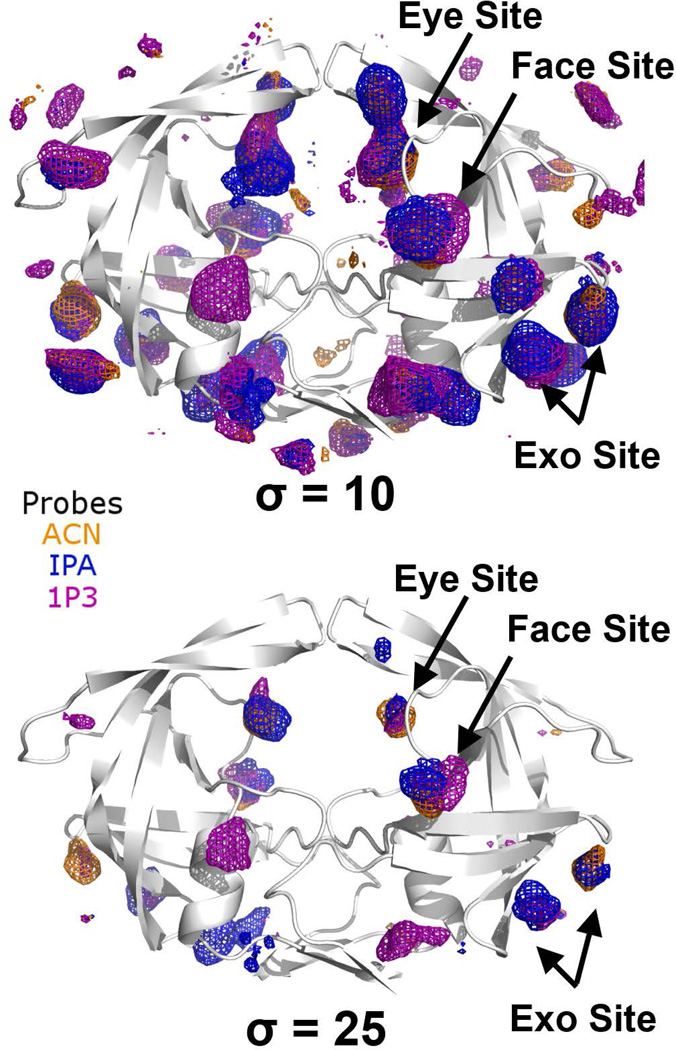

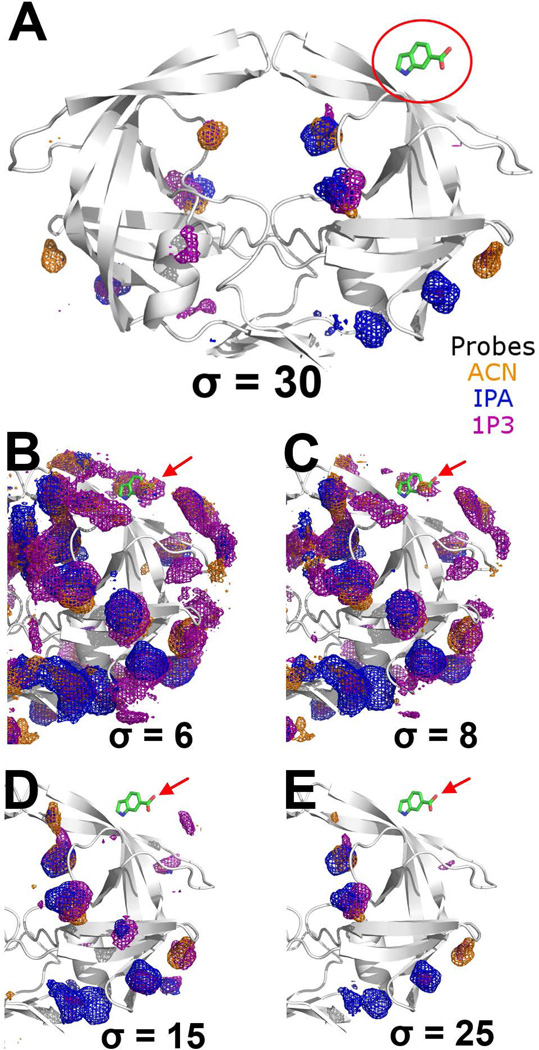

Low Probe Concentration Yields Higher Signal-to Noise Ratios

We found that a 5% concentration for probe solvent demonstrated significant advantages over the 50% MixMD method. For the 50% probe-water MixMD of apo HIVp in semi-open conformation (Figure 1), the occupancy maps identified the Exo site, Eye site, and Face site, but numerous spurious sites are identified at low contour levels (σ < 6). The gap between intense and weak occupancies is narrow (Δσ < 3) and a contour level of σ = 10 would effectively eliminate all probe occupancies. In contrast, 5% probe-water MixMD found the same hot spots identified by 50% MixMD, yet the weak and intense occupancies are separated by a large difference (contours of σ=10 vs contours of σ≥25). The most intense binding hot spots remained at 30 σ values above the basal level of occupancy, effectively eliminating most spurious sites (Figure 3). Hence, 5% MixMD provides a better signal-to-noise ratio and clearer resolution of binding hot spots than 50% probe-water MixMD could achieve. Typically, most weak occupancies can be eliminated by σ > 15. At contour level σ = 25, only the most intense binding hot spots for the apo state remained: the Exo site, the Eye site, and the Face site. Therefore, the 5% solvation strategy should be applied in the majority of MixMD studies, and an occupancy contour level of ≥ 20 σ should be used as a standard cutoff for defining a binding hot spot.

Figure 3.

Probe occupancies of 5% probe-water solution in MixMD of HIVp. ACN, IPA, and 1P3 probe occupancies are shown as orange, blue, and purple meshes, respectively. Increasing the contour level from σ = 10 to 25 eliminates weak occupancies. Very few spurious occupancies are observed compared to the occupancy maps of 50% MixMD (Figure 1). All three probes occupancies overlap in the Exo, Eye, and Face sites.

Binding Hot Spots in the Semi-Open State of HIVp

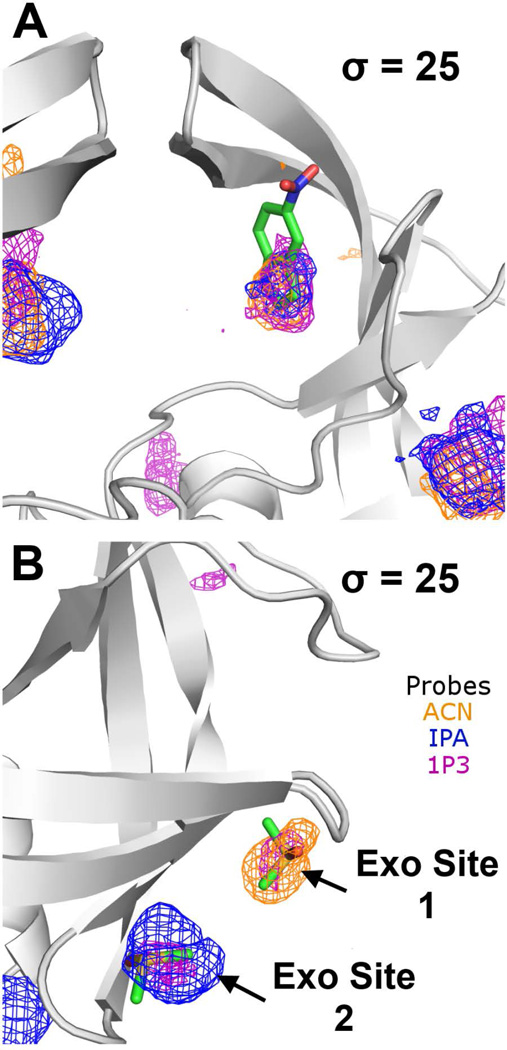

Using a high contour threshold (σ = 25) with the 5% solutions, the Exo, Eye, and Face sites are identified as the binding hot spots for the semi-open state. For the Eye site, it is associated with HIVp in semi-open and open conformations since it requires the flaps to undock from the site to allow access; HIVp in complex with active site inhibitors adopts a closed conformation, where the flaps close down and occupy the Eye site, rendering this site unavailable for ligand binding. Importantly, the Eye site has been confirmed by X-ray crystallography, in which the probe occupancies overlap with the crystallized fragment 5NI (Figure 4A).57 A ligand similar to this fragment has also been identified and demonstrated to modulate HIVp proteolytic activity in both wild-type and multidrug-resistant HIVp.56

Figure 4.

Ligands (shown in sticks with green carbons) that are seen in some crystal structures of HIVp overlap with the probe occupancies at the Exo and Eye sites. (A) Fragment 5NI overlaps with the Eye site probe occupancies. (B) Buffer additives (PDB: 3KFP; two DMSO shown) overlap with the Exo site probe occupancies. Probe occupancies of 5% ACN-water, IPA-water, and 1P3-water systems are shown as orange, blue, and purple meshes, respectively. All probe occupancies are shown at contour level σ = 25.

ACN, IPA, and 1P3 consistently mapped the Exo site, a long shallow cleft formed on the side of HIVp and situated far away from the peptide-binding site and the Eye site. MixMD indicates the Exo site is composed of two discrete hot spots separated by ~8.0 Å. Accordingly, the Exo site can be divided into two subsites, Exo site 1 (near G16, L63 and A71) and Exo site 2 (near I64, G65 and K70). Crystallographic evidence in structures such as 3KFP and 3KFN57 support the existence of these two subsites, in which buffer additives (e.g., acetate and DMSO) are found to overlap with the proposed Exo subsites (Figure 4B). The Exo site has been proposed to function as an allosteric site for regulation of flap movement.62,63 Unlike the Eye site, currently no known ligand has been developed to target the Exo site.

Based on the HIVp co-crystals of small fragments such as 3KFR and 3KFS, Perryman et al.57 proposed the Flap site, a ligand binding site on top/outside of the flap. Our MixMD results indicate that the Flap site is less favorable than other hotspots because all MixMD simulations have weaker probe occupancies at this site. For 50% MixMD, a low contour of σ = 5 effectively eliminates the probe occupancies at the Flap site. For 5% MixMD, a contour above σ = 10 is sufficient to remove all probe occupancies observed at the Flap site along with other spurious occupancies (Figure 5). Although the probe occupancy at this site is weak, MixMD’s ability to map the Flap site shows some favorable physical and chemical properties to attract hydrophobic organic molecules. Protein denaturation experiments suggest that the Flap site attracts small molecules and the subsequent binding regulates protein conformations of the flaps of HIV-1p.58

Figure 5.

Probe occupancies near the Flap site are shown for the 5% probe-water MixMD of HIVp in its semi-open conformation. (A) At very high occupancy contour level (σ = 30), there are no observable probe occupancies at the Flap site. (B–E) The occupancy intensity is shown at σ = 6, 8, 15, and 25 to better demonstrate the weak occupancies at low σ values. As the contour level increases, the probe occupancies at the Flap site disappear, showing that the interaction is much weaker than the Eye, Face, and Exo sites. The position of the fragment indole-6-carboxylate, indicated by the red arrow, was taken from PDB: 3KFR. Probe occupancies of ACN-water, IPA-water, and 1P3-water systems are shown as orange, blue, and purple meshes, respectively.

It is difficult to compare our simulation maps for the semi-open state to maps produced by other groups that use mixed-solvent MD. Only MacKerrel and coworkers have simulated an apo form.22 Their analysis focused on the catalytic site, and other potential sites were not discussed or shown. However, they did note that the maps for hotspots in the peptide binding site were poor when using the apo, semi-open state. They found that the aromatic/aliphatic maps of the S1, S2, S1’, and S2’ sub-pockets were much better from their simulation of the closed form of HIVp. We had similar results as outlined in the next section. Barril and coworkers24 have also simulated the closed form of HIVp in mixed-solvent simulations, but they did not use any aromatic probes, which are a significant feature in our maps and MacKerrel’s. Also, aromatic groups are common features in HIVp inhibitors, so it is hard to compare Barril’s maps to other experimental data.

MixMD of HIVp in Its Closed Conformation

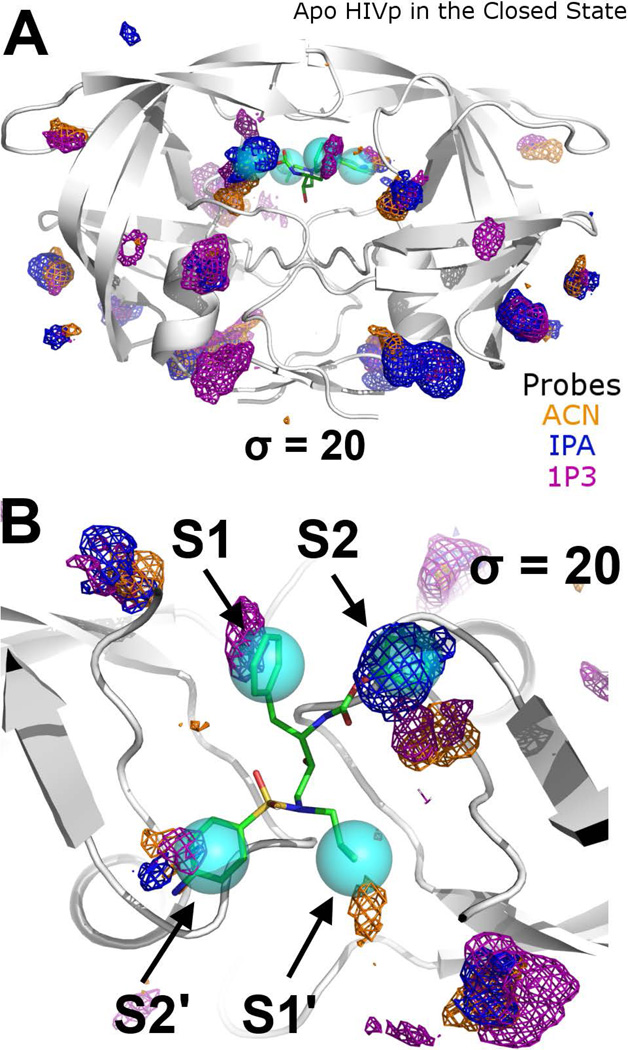

We observed that the catalytic, peptide-binding site of HIVp in the semi-open conformation was mapped weakly in both 5% and 50% ACN, IPA, and 1P3 MixMD. All occupancy grid points were less than σ=15, and they were not seen when visualizing the maps at higher σ values. The central competitive site is a well known, druggable site targeted in HIV treatment, so we were surprised at the weak mapping. Of course, the protein conformation plays a significant role in dictating the favorability of the probe binding, and the semi-open positions of the flap residues lining the peptide-binding site must provide poorer contacts and less binding surface to attract organic probes. To confirm that the weak probe occupancies in the peptide-binding site was due to the semi-open flap conformations, layered 5% probe-water MixMD were performed for HIVp in the closed conformation. The inhibitor amprenavir, found in the crystal structure 1HPV,64 was used as reference for the positions of the known hot spots in the peptide-binding site; the centroids of the 4 moieties of amprenavir (phenyl, 4-aminobenzenesulfonyl, isobutyl, and tetrahydrofuran-3-yl groups) were marked as the center of the S1, S2, S1’, and S2’ binding pockets, respectively.

The structure of HIV-1p in the closed-state simulations remained closed in all trajectories. The handedness of the flaps remained the same as the reference HIV1-p in closed conformation, and the flap-RMSD did not vary much in all trajectories (median ~ 1.6 Å). Our aim was to map the closed-state specifically, so the trajectories were kept short. Previous studies have shown that a global change to the open state requires simulations of 40–50 ns.34 MixMD of HIVp in the closed conformation results in strong occupancy maps for ACN, IPA, and 1P3 in the Exo and Face sites with grid points >25 σ. As expected, no occupancy was observed at the Eye site because it was occupied by the protein in the closed conformation and was not available for probe sampling. In contrast, slightly weaker probe occupancies were found in the S1/S1’ and S2/S2’ pockets at contour level σ = 20 (Figure 6). It is interesting that the occupancies at these pockets are slightly weaker than those of the Exo and the Face sites. This implies that the individual sub-pockets for peptide substrates have weaker affinity for organic molecules; however, ligands that can simultaneously bind to multiple sub-pockets must gain significant synergy with increased binding affinity and selectivity, as seen in many HIVp inhibitors that occupy all four binding pockets.

Figure 6.

Probe occupancy maps for 5% probe-water MixMD at the peptide-binding site of HIVp in its closed conformation. Both (A) side and (B) top views are shown. The position of amprenavir (shown in sticks with green carbons) from the structure 1HPV is superimposed on the MixMD maps to demonstrate the agreement in the mapping of hot spots that are occupied in all drug-like inhibitors of HIVp. All three types of probes mapped the binding hot spots at the S1/S1’ and S2/S2’ sub-pockets. The cyan spheres represent the centroids of the functional groups amprenavir. Probe occupancies of ACN-water, IPA-water, and 1P3-water systems are shown as orange, blue, and purple meshes, respectively.

Since Perryman et al.57 identified the Flap site in crystal structures of HIVp in closed conformation, we checked the probe occupancies at the Flap site in the MixMD with closed HIVp. Similar to the results from MixMD with semi-open HIVp, only weak probe occupancies were observed at this site. The grid points had occupancies <10 σ in the 5% probe-water MixMD.

Mapping the Central Binding Site Using an Amide Probe Solvent

Since the natural substrates of protease enzymes are peptides that contain amide linkage, we performed MixMD using a probe with peptidic character, NMA.39 We chose NMA since it is one of the simplest molecules that contains an amide functional group to mimic the hydrogen-bond donating and accepting patterns of a natural substrate.

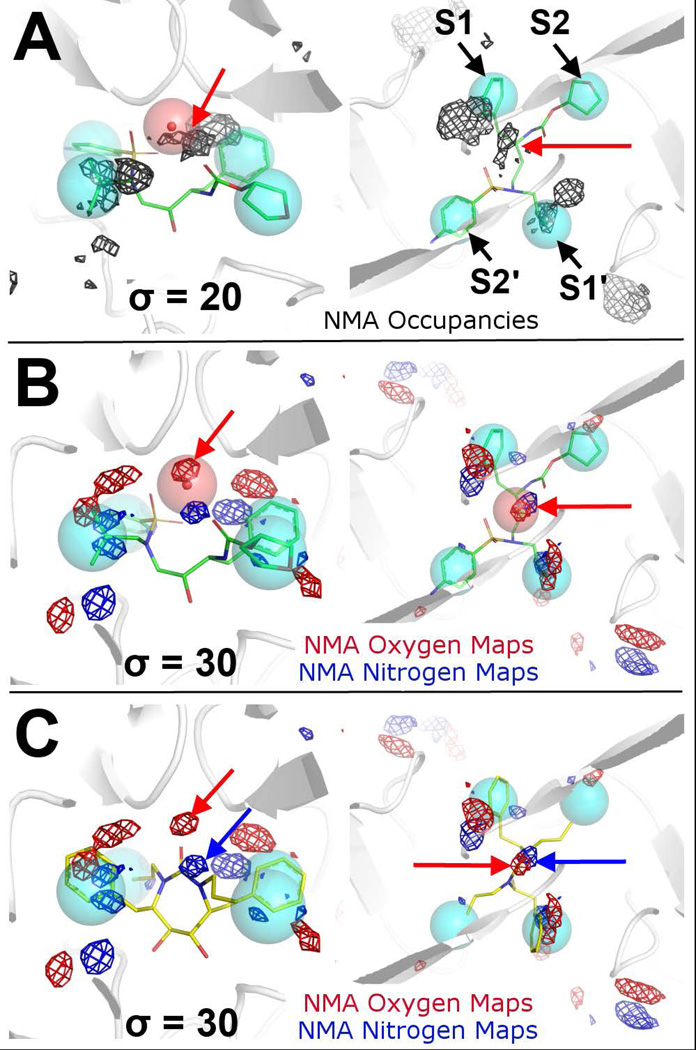

Similar to other probes used in MixMD with closed HIVp, the occupancy map of NMA identified the binding hot spots in the Exo site, Face site, and the S1/S1’ and S2/S2’ binding pockets in the peptide-binding site. Importantly, NMA has a relatively stronger occupancy in the peptide-binding site than ACN, IPA, and 1P3 (Figure 7A). In addition, NMA occupancy was found to overlap with a structural water molecule under the flaps65 seen in many crystal structures of HIVp bound with various inhibitors (Figure 7A). This flap water has a functional role as it mediates the positioning of the flaps and the bound inhibitor through formation of an extensive hydrogen-bond network. In the case of amprenavir, this flap water coordinates I50/I50’ of the flaps, the carbonyl oxygen, and one of the sulfonyl oxygens of the inhibitor in a tetrahedral geometry. Analyzing the water occupancy maps from the ACN-water, IPA-water, 1P3-water, and NMA-water MixMD, we did not see the flap water molecule being mapped by the MixMD, which implies that the water position is most favorable when an inhibitor is present to provide part of the hydrogen-bonding network.

Figure 7.

Probe occupancies of 5% NMA-water MixMD in the peptide-binding site of HIVp in its closed conformation. Side views are on the left and top views are on the right. (A) Full-molecule NMA occupancy is shown as black mesh, and it maps relevant hot spots in the peptide-binding site. The red arrow illustrates the crystallographic water under the flaps. The NMA occupancy map overlaps with this flap water that forms extensive hydrogen-bonds with the flaps and the bound ligand, amprenavir (sticks with green carbons). (B) Atomic occupancies of the carbonyl oxygen (O) and amide nitrogen (N) of NMA are shown as red and blue mesh, respectively. An O occupancy overlaps with the flap water (red arrow). (C) An O occupancy (red arrow) is in close proximity to the carbonyl oxygen of XK216 (shown in sticks with yellow carbons), a cyclic urea inhibitor found in PDB 1HWR. An N occupancy (blue arrow) is found next to the carbamide nitrogen of XK216.

To further examine the interactions between NMA and the protein, the full-molecule NMA occupancy map was broken down by atom types, yielding the carbonyl oxygen (O) and amide nitrogen (N) occupancy maps. These individual maps matched well with the inhibitor amprenavir in 1HPV, in which O and N occupancies mapped the oxygen position of the tetrahydrofuran-3-yl group and the nitrogen of the 4-aminophenyl group, respectively. Significantly, the O maps have very high occupancy exactly in that position for the flap water (Figure 7B), which explains why the water in the MixMD simulations did not map the position. The mapping pattern of NMA was also confirmed by the crystal structure of HIVp in complex with XK216, a cyclic urea inhibitor (PDB: 1HWR66). The NMA O occupancy mapped to the flap water was found to overlap with the carbonyl oxygen of the inhibitor, which displaces the flap water and forms an extensive hydrogen-bond network with the flaps. On the other hand, N occupancy was found to map near the carbamide nitrogen of XK216 (Figure 7C). These observations strongly support the accuracy of MixMD. Furthermore, NMA-water MixMD suggests that in addition to the general probes such as ACN, IPA, and 1P3, NMA can be used as a specialty probe for peptide-binding sites.

MixMD Identifies Shallow Protein Surfaces and Crystal-Packing Interfaces

Among the hot spots of HIVp that have been consistently mapped by ACN, IPA, and 1P3 in the 50% and 5% MixMD, only the Eye site and the peptide-binding site are concave cavities that are typically associated with small molecule binding. The other identified hot spots, the Face site (a depression near the catalytic site of HIVp composed of L20 – I24 and T80 – I84) and Exo site are patches of shallow protein surface. Currently, these sites are not known to have function and they might even be regarded as spurious hot spots upon initial investigation.

MixMD identifies hot spots on protein surface that can be readily desolvated and bind organic molecules. Such hot spots may also function as site for protein-protein contacts, such as the p53-MDM2 protein interface.67 Such interfaces have been observed and explained by Liepinsh and Otting10 when they compared the “SAR by NMR” result of HEWL to the MSCS results by Mattos et al.,8 in which many crystallographically determined binding sites other than the peptide-binding site, usually near the crystal contact regions, are absent in the NMR result. A similar observation has also been described by Mattos et al.,7 where MSCS of elastase identified surface sites in addition to the known substrate-binding sites. These observations are similar to the surface sites found in our probe occupancies of HIVp, which cluster at protein surface that away from the known binding sites. In order to understand these observations and the relevance of the surface sites that are consistently mapped by various probes in MixMD, we compared the probe occupancy maps to crystal structures of HIVp available in the public domain.

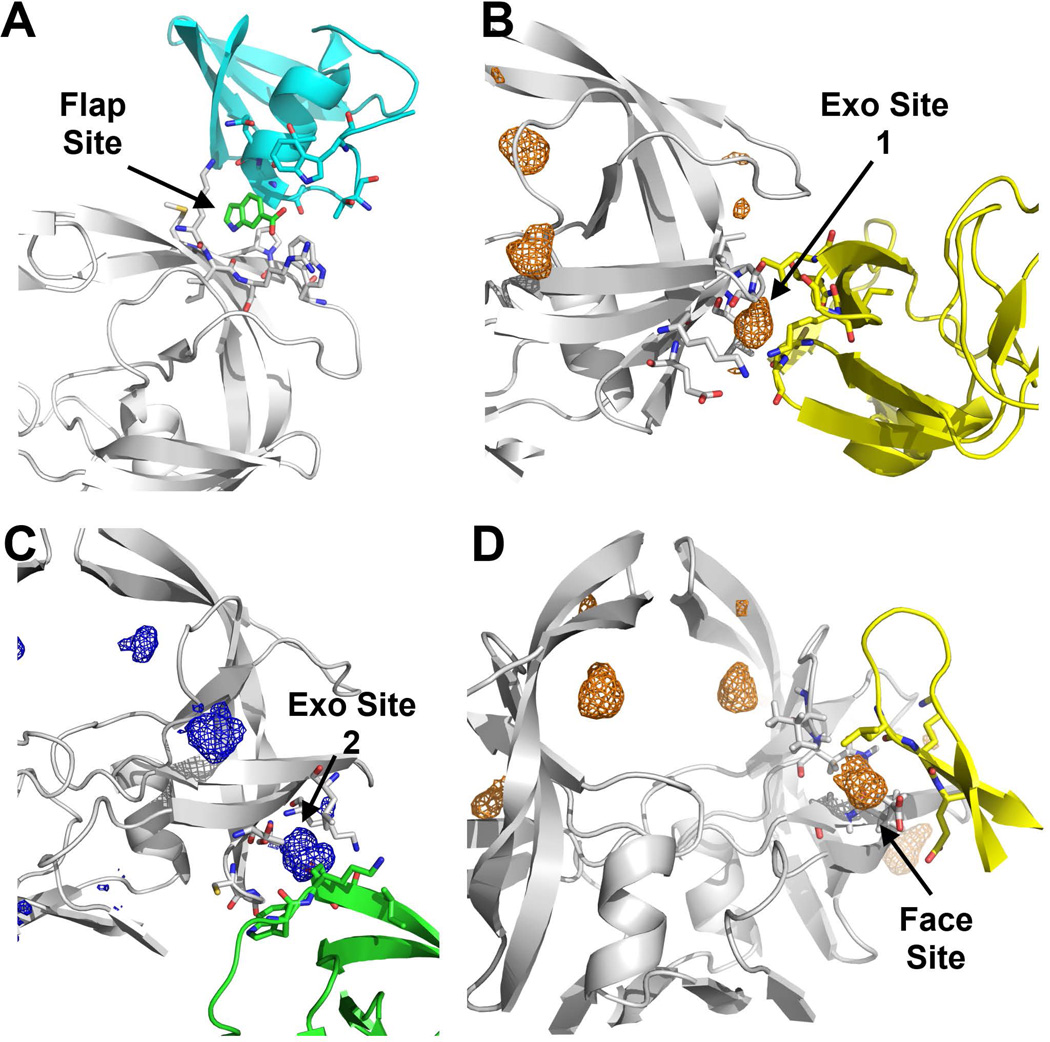

We obtained 347 crystal structures of ligand-bound HIVp and related proteases that have a diffraction resolution better than 2.5 Å from Binding MOAD.68 Together with the apo structures, these structures were grouped into 17 crystal symmetry groups, and the symmetry units were generated and visualized through PyMOL. We found that several crystal symmetry partners have crystal contacts at or near the Exo, Face, and Flap sites (Figure 8). Such clustering of probes at or near the crystal contact regions has been observed in the MCSC of HEWL8 and elastase7 as well. These experimental structures confirm our observation of ACN, IPA, and 1P3 occupancies at the shallow protein surface and support the accuracy of MixMD.

Figure 8.

Probe occupancies of 5% probe-water MixMD are compared to crystal contact surfaces. (A) In structure 3KFR, the small molecule indole-6-carboxylate (green sticks) resides in the Flap site, a binding pocket formed by symmetry contacts (cyan ribbons) of neighboring HIVp. The probe occupancies observed at this site were weak in all of our simulations. (B) In structure 2AZC, Exo site 1 has crystal contacts with an Exo site of its symmetry partner (yellow ribbon). For clarity, only ACN occupancy is shown here. (C) In structure 1DAZ, Exo site 2 forms crystal contacts with its symmetry partner (green ribbons). Only IPA occupancy is shown for clarity. (D) In a second example from 2AZC, the Face site is in contact with a symmetry partner (yellow ribbon); note it is not the same contact partner that is seen in (B). Only ACN occupancy is shown for clarity. All probe occupancies are shown at σ = 25.

Interestingly, MixMD suggests the Flap site is a weak binding hot spot. The presence of resolved fragments in the co-crystals of HIVp (3KFR and 3KFS) may result from the formation of a pseudo binding pocket at the interface of the crystal contacts, which would otherwise not be present under normal conditions. In the crystal structures 3KFR and 3KFS, which are in the symmetry group P-212121, the Flap site of the asymmetric unit forms crystal contacts with the dimer interface of its symmetry unit (residues T4, W6, T91 – G94), which may explain the formation of a binding pocket for the fragments (Figure 8A). This result suggests that crystal structures should be examined carefully, especially when small molecules are found on shallow protein surface, to avoid misinterpretation of the binding of small molecules to a false site.28

The Exo site appears to be a favored interface for non-specific crystal contacts. We found that crystal structures of HIVp in symmetry groups I-222 (e.g., 1ZBG), I-4122 (e.g., 2AZC), P-1121 (e.g., 1A8K), P-212121 (e.g., 1DAZ), P-61 (e.g., 1A8G), and P-6122 (e.g., 1UPJ) have crystal contacts at or near the Exo site. Specifically, we observed that in symmetry groups I-222, I-4122, P-1121, P-212121, P-61, and P-6122 one of the symmetry units is in close proximity to the Exo site 1 of the asymmetric unit (Figure 8B).69 Probe occupancies from various maps can be found clustered in the crystal contacts between the two units, similar to the observation described by Mattos et al.12 On the other hand, symmetry groups P-1121, P-212121, and P-6122 have symmetry units in close proximity to the Exo site 2. In 1DAZ,70 crystal contacts are formed between the Exo site 2 of the asymmetric unit and the flap of its symmetry unit (residue P44 – I54) (Figure 8C). Probe occupancies from various maps were found to populate between the two contacting units.

The crystal 2AZC, belongs to the I-4122 symmetry group, has crystal contacts that overlap with the ACN, IPA, and 1P3 probe occupancies at the Face site (Figure 8D): crystal contacts formed between the Face site of the asymmetric unit and a beta-sheet structure near the dimer interface (residues Q18 – E21) of its symmetry unit. Interestingly, the Face Site residues of HIVp are relatively conserved among similar aspartic proteases from other retroviruses. Using the sequence alignment tool CLUSTAL W v1.8171 available through the SDSC Biology Workbench 3.2 online server (http://workbench.sdsc.edu), the sequence alignment of the retroviral proteases was examined: the protease of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV, 50% identity to HIVp), HIV type-2 (48% identity to HIVp), equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV, 32% identity to HIVp) and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV, 21% identity to HIVp). Several residues of the Face site, most of them hydrophobic, are relatively conserved among the examined aspartic proteases (Table 3). This constitution of hydrophobic residues at the Face Site and the tendency of this site to bind hydrophobic probes suggest that this patch of protein surface may function as a docking site for the client polyproteins. Association to this surface may provide some enthalpic compensation through van der Waals interactions and entropic assistance with the displacement of the loosely bound water molecules on this hydrophobic protein surface.

Table 3.

Residue similarity at Face site of several viral aspartic proteases

| Identity (HIV1p) |

Residues (HIV-1 Protease) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | ||

| HIV-1 | -- | K | E | A | L | L | T | P | V | N | I |

| SIV | 50% | V | E | V | L | L | T | P | I | N | I |

| HIV-2 | 48% | V | E | V | L | L | T | P | I | N | I |

| EIAV | 32% | L | N | V | L | L | I | P | V | T | I |

| FIV | 21% | I | K | F | L | L | V | C | V | L | L |

CONCLUSION

Many computational techniques that search for binding hot spots on protein surfaces rely on a static crystal structure and do not account for protein dynamics or the effect of probe-water competition. These techniques usually suffer from the many spurious hot spots identified on the protein surface and the inability to identify cryptic sites. To bypass these shortcomings, we used a dynamic sampling method, MixMD, and improved its mapping by lowering the probe concentration. MixMD uses miscible organic probes and does not introduce unphysical parameters to prevent the undesirable aggregation problem of hydrophobic probes. In our test case of HIV-1p, MixMD successfully identified the catalytic site in the closed state. In the semi-open state, MixMD identifies the allosteric Eye site and crystal contact sites in HIVp that are supported by crystallographic evidence. Interestingly, MixMD identifies binding hot spots on the shallow protein surface that are known to form crystal contacts, which explains the observation of strong probe occupancy at locations not known for ligand binding. This information by MixMD would be very useful for identifying potential binding sites and constructing pharmacophore models for structural-based drug discovery projects. Of course, the next phase of our development of MixMD is to quantify our maps and derive binding free energies for the probes, using several diverse proteins.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM65372). We thank Drs. C. David Stout and Alex Perryman for helpful discussions and sharing the crystal structure of 5NI bound HIV-1 protease. We thank the National Institute for Computational Sciences for granting time on Kraken Cray XT5 (Project title TG-MCB110089); that resource is supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant numbers 0711134, 0933959, 1041709, and 1041710 and the University of Tennessee (http://www.nics.tennessee.edu). We thank Dr. Charles L. Brooks III for providing access to the Gollum clusters at the University of Michigan. We thank the IBM Matching Grants Program for granting the GPU units for high-performance molecular dynamics simulations. PMUU is grateful for receiving fellowships from Fred W. Lyons and the University of Michigan Regents.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 5NI

5-nitroindole

- ACN

acetonitrile

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ED

essential dynamics

- HEWL

hen egg-white lysozyme

- HIVp

human immunodeficiency virus type-1 protease

- IPA

isopropanol

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MixMD

mixed-probe molecular dynamics

- MSCS

multiple-solvent crystal structure

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- 1P3

pyrimidine

- RDF

radial distribution function

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

Footnotes

Tables report the ratio of probes to water in the 50% w/w and 5% v/v solution environments. Eigenvector data are given. RDFs are used to show even mixing of the co-solvent environments. RMSDs of the protein over time are given.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ringe D, Mattos C. Analysis of the binding surfaces of proteins. Med Res Rev. 1999;19:321–331. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199907)19:4<321::aid-med5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soga S, Shirai H, Kobori M, Hirayama N. Use of amino acid composition to predict ligand-binding sites. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:400–406. doi: 10.1021/ci6002202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soga S, Shirai H, Kobori M, Hirayama N. Identification of the druggable concavity in homology models using the PLB index. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:2287–2292. doi: 10.1021/ci7002363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai CJ, Lin SL, Wolfson HJ, Nussinov R. Studies of protein-protein interfaces: A statistical analysis of the hydrophobic effect. Protein Sci. 1997;6:53–64. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen KN, Bellamacina CR, Ding X, Jeffery CJ, Mattos C, et al. An Experimental Approach to Mapping the Binding Surfaces of Crystalline Proteins. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:2605–2611. [Google Scholar]

- 6.English AC, Groom CR, Hubbard RE. Experimental and computational mapping of the binding surface of a crystalline protein. Protein Eng. 2001;14:47–59. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattos C, Bellamacina CR, Peisach E, Pereira A, Vitkup D, et al. Multiple solvent crystal structures: Probing binding sites, plasticity and hydration. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1471–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattos C, Ringe D. Locating and characterizing binding sites on proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt0596-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Zhu G, Huang Q, Qian M, Shao M, et al. X-ray studies on cross-linked lysozyme crystals in acetonitrile-water mixture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1384:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liepinsh E, Otting G. Organic solvents identify specific ligand binding sites on protein surfaces. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nbt0397-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuker SB, Hajduk PJ, Meadows RP, Fesik SW. Discovering high-affinity ligands for proteins: SAR by NMR. Science. 1996;274:1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenke R, Kozakov D, Chuang GY, Beglov D, Hall D, et al. Fragment-based identification of druggable ‘hot spots’ of proteins using Fourier domain correlation techniques. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:621–627. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis S, Kortvelyesi T, Vajda S. Computational mapping identifies the binding sites of organic solvents on proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4290–4295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062398499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gohlke H, Hendlich M, Klebe G. Knowledge-based scoring function to predict protein-ligand interactions. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:337–356. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodford PJ. A computational procedure for determining energetically favorable binding sites on biologically important macromolecules. J Med Chem. 1985;28:849–857. doi: 10.1021/jm00145a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landon MR, Amaro RE, Baron R, Ngan CH, Ozonoff D, et al. Novel druggable hot spots in avian influenza neuraminidase H5N1 revealed by computational solvent mapping of a reduced and representative receptor ensemble. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;71:106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranker A, Karplus M. Functionality maps of binding sites: A multiple copy simultaneous search method. Proteins. 1991;11:29–34. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakan A, Nevins N, Lakdawala AS, Bahar I. Druggability Assessment of Allosteric Proteins by Dynamics Simulations in the Presence of Probe Molecules. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:2435–2447. doi: 10.1021/ct300117j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster TJ, MacKerell AD, Jr, Guvench O. Balancing target flexibility and target denaturation in computational fragment-based inhibitor discovery. J Comput Chem. 2012;33:1880–1891. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guvench O, MacKerell AD., Jr Computational fragment-based binding site identification by ligand competitive saturation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:1000435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raman EP, Vanommeslaeghe K, Mackerell AD., Jr Site-Specific Fragment Identification Guided by Single-Step Free Energy Perturbation Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:3513–3525. doi: 10.1021/ct300088r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raman EP, Yu W, Guvench O, Mackerell AD., Jr Reproducing crystal binding modes of ligand functional groups using Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:877–896. doi: 10.1021/ci100462t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seco J, Luque FJ, Barril X. Binding site detection and druggability index from first principles. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2363–2371. doi: 10.1021/jm801385d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez-Garcia D, Barril X. Molecular simulations with solvent competition quantify water displaceability and provide accurate interaction maps of protein binding sites. J Med Chem. 2014;57:8530–8539. doi: 10.1021/jm5010418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakkaraju SK, Yu W, Raman EP, Hershfeld AV, Fang L, et al. Mapping functional group free energy patterns at protein occluded sites: Nuclear receptors and G-protein coupled receptors. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:700–708. doi: 10.1021/ci500729k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knox C, Law V, Jewison T, Liu P, Ly S, et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1035–1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lexa KW, Carlson HA. Full protein flexibility is essential for proper hot-spot mapping. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:200–202. doi: 10.1021/ja1079332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lexa KW, Carlson HA. Improving protocols for protein mapping through proper comparison to crystallography data. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:391–402. doi: 10.1021/ci300430v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lexa KW, Goh GB, Carlson HA. Parameter choice matters: Validating probe parameters for use in mixed-solvent simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:2190–2199. doi: 10.1021/ci400741u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sevier CS, Kaiser CA. Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinelli S, Liu QZ, Alzari PM, Hirel PH, Poljak RJ. The three-dimensional structure of the aspartyl protease from the HIV-1 isolate BRU. Biochimie. 1991;73:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sham HL, Zhao C, Stewart KD, Betebenner DA, Lin S, et al. A novel, picomolar inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. J Med Chem. 1996;39:392–397. doi: 10.1021/jm9507183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, et al. AMBER 11. San Francisco: University of California; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornak V, Okur A, Rizzo RC, Simmerling C. HIV-1 protease flaps spontaneously open and reclose in molecular dynamics simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical Integration of the Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints: Molecular Dynamics of n-Alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darden TA, York DM, Pedersen LG. Particle Mesh Ewald An N.log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrea TA, Swope WC, Andersen HC. The Role of Long Ranged Forces in Determining the Structure and Properties of Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:4576–4584. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grabuleda X, Jaime C, Kollman PA. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies of Liquid Acetonitrile: New Site Model. J Comput Chem. 2000;21:901–908. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, Tirado-Rives J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen WL, McDonald NA. Development of an All-Atom Force Field for Hetercycles Properties of Liquid Pyridine and Diazenes. J Mol Struct (Theochem) 1998;424:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goetz AW, Williamson MJ, Xu D, Poole D, Grand SL, et al. Routine Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations with AMBER - Part I: Generalized Born. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:1542–1555. doi: 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amadei A, Linssen AB, Berendsen HJ. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia AE. Large-amplitude nonlinear motions in proteins. Phys Rev Lett. 1992;68:2696–2699. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mongan J. Interactive essential dynamics. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2004;18:433–436. doi: 10.1007/s10822-004-4121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrett CP, Hall BA, Noble ME. Dynamite: A simple way to gain insight into protein motions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2280–2287. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 1.5.0.1, Schrödinger, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, Davis LJ, Heimbach JC, et al. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krausslich HG. Human immunodeficiency virus proteinase dimer as component of the viral polyprotein prevents particle assembly and viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3213–3217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galiano L, Ding F, Veloro AM, Blackburn ME, Simmerling C, et al. Drug pressure selected mutations in HIV-1 protease alter flap conformations. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:430–431. doi: 10.1021/ja807531v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, et al. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishima R, Louis JM. A diverse view of protein dynamics from NMR studies of HIV-1 protease flaps. Proteins. 2008;70:1408–1415. doi: 10.1002/prot.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadiq SK, De Fabritiis G. Explicit solvent dynamics and energetics of HIV-1 protease flap opening and closing. Proteins. 2010;78:2873–2885. doi: 10.1002/prot.22806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damm KL, Ung PM, Quintero JJ, Gestwicki JE, Carlson HA. A poke in the eye: Inhibiting HIV-1 protease through its flap-recognition pocket. Biopolymers. 2008;89:643–652. doi: 10.1002/bip.20993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ung PM, Dunbar JB, Jr, Gestwicki JE, Carlson HA. An allosteric modulator of HIV-1 protease shows equipotent inhibition of wild-type and drug-resistant proteases. J Med Chem. 2014;57:6468–6478. doi: 10.1021/jm5008352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perryman AL, Zhang Q, Soutter HH, Rosenfeld R, McRee DE, et al. Fragment-based screen against HIV protease. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;75:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tiefenbrunn T, Forli S, Baksh MM, Chang MW, Happer M, et al. Small molecule regulation of protein conformation by binding in the Flap of HIV protease. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1223–1231. doi: 10.1021/cb300611p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raman EP, Yu W, Lakkaraju SK, MacKerell AD., Jr Inclusion of multiple fragment types in the site identification by ligand competitive saturation (SILCS) approach. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:3384–3398. doi: 10.1021/ci4005628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu W, Lakkaraju SK, Raman EP, MacKerell AD., Jr Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) assisted pharmacophore modeling. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2014;28:491–507. doi: 10.1007/s10822-014-9728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jordan SP, Zugay J, Darke PL, Kuo LC. Activity and dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus protease as a function of solvent composition and enzyme concentration. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20028–20032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perryman AL, Lin JH, McCammon JA. Restrained molecular dynamics simulations of HIV-1 protease: The first step in validating a new target for drug design. Biopolymers. 2006;82:272–284. doi: 10.1002/bip.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mittal S, Cai Y, Nalam MN, Bolon DN, Schiffer CA. Hydrophobic core flexibility modulates enzyme activity in HIV-1 protease. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4163–4168. doi: 10.1021/ja2095766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim EE, Baker CT, Dwyer MD, Murcko MA, Rao BG, et al. Crystal Structure of HIV-1 Protease in Complex with VX-478, a Potent and Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of the Enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:1181–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller M, Schneider J, Sathyanarayana BK, Toth MV, Marshall GR, et al. Structure of complex of synthetic HIV-1 protease with a substrate-based inhibitor at 2.3 A resolution. Science. 1989;246:1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.2686029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ala PJ, DeLoskey RJ, Huston EE, Jadhav PK, Lam PY, et al. Molecular recognition of cyclic urea HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12325–12331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Moreau J, et al. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science. 1996;274:948–953. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu L, Benson ML, Smith RD, Lerner MG, Carlson HA. Binding MOAD (Mother Of All Databases) Proteins. 2005;60:333–340. doi: 10.1002/prot.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heaslet H, Kutilek V, Morris GM, Lin YC, Elder JH, et al. Structural insights into the mechanisms of drug resistance in HIV-1 protease NL4-3. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:967–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahalingam B, Louis JM, Reed CC, Adomat JM, Krouse J, et al. Structural and kinetic analysis of drug resistant mutants of HIV-1 protease. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.