Abstract

This paper examines associations between the Great Recession and four aspects of 9-year olds’ behavior—aggression (externalizing), anxiety/depression (internalizing), alcohol and drug use, and vandalism—using the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a longitudinal birth cohort drawn from twenty U.S. cities (21%, White, 50% African-American, 26% Hispanic, and 3% other race/ethnicity). The study was in the field for the 9-year follow-up right before and during the Great Recession (2007-2010) (N = 3,311). Interview dates (month) were linked to the national Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI), calculated from a national probability sample drawn monthly to assess consumer confidence and uncertainty about the economy, as well as to data on local unemployment rates. Controlling for city-fixed effects and extensive controls (including prior child behavior at age 5), we find that greater uncertainty as measured by the CSI was associated with higher rates of all four behavior problems for boys (in both maternal and child reports). Such associations were not found for girls (all gender differences were significant). Links between the CSI and boys’ behavior problems were concentrated in single-parent families and were partially explained by parenting behaviors. Local unemployment rates, in contrast, had fewer associations with children's behavior, suggesting that in the Great Recession, what was most meaningful for child behavior problems was the uncertainty about the national economy, rather than local labor markets.

Keywords: Child behavior, Delinquency, Fragile Families, Parenting, Unemployment, Consumer Confidence

The Great Recession was the most severe economic downturn in the United States since the Great Depression. The Great Recession officially began in December, 2007 with two consecutive quarters of decline in real Gross Domestic Product, and ended in June, 2009 (NBER, 2014). It was marked by a collapse in the housing market and widespread home foreclosures, as well as dramatic increases in the national unemployment rate to nearly 10% from a pre-recession rate of 5%, and with large cities experiencing unemployment rates of 11% and higher (Goodman & Mance, 2011). News coverage of the stark increases in home foreclosures and unemployment as well as a number of bank rescues and collapses was widespread and had large effects on the general public's confidence in the economy and in their own financial wellbeing (Anat & Jamison, 2012; Ayers, Althouse, Allem, Childers, Zafar, Latkin, Ribisi, & Brownstein, 2012).

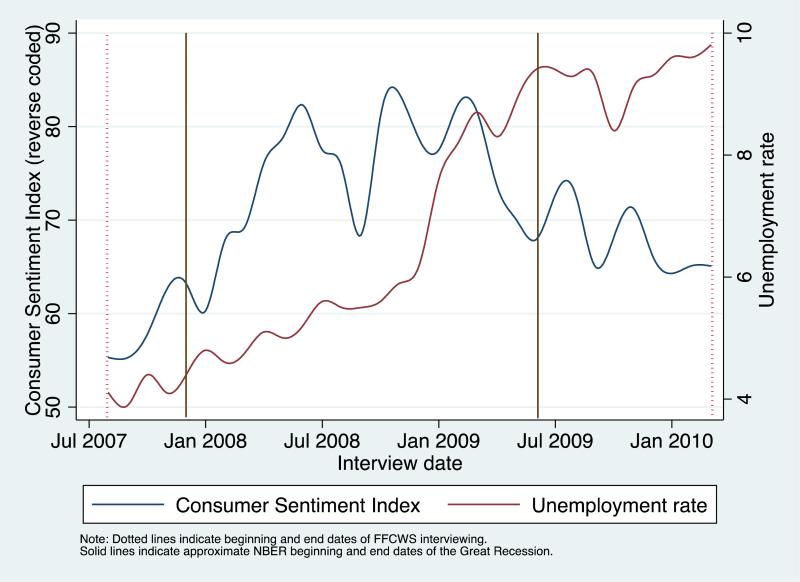

The dramatic decline in consumer confidence during the Great Recession is reflected in a decline in the national Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI). The CSI is an index of consumer confidence produced from a monthly phone survey which asks a series of questions about people's perception of their personal finances and their opinion about the state of the economy as a whole. CSI is normalized to have a baseline value of 100 in December, 1964, and is a leading indicator of events such as recessions (Zagorski & McDonnell, 1995). The CSI fell from an average of 86.5 in the 11 months prior to the recession to an average of 64.2 during the Great Recession. Half of those surveyed in the national CSI survey at the height of the Great Recession in 2009 reported that their financial situation was worse than the year before, in contrast to only 25% of those surveyed pre-recession in 2006 (Petev & Pistaferri, 2012).

Did the national shock associated with the Great Recession affect child wellbeing? In this paper, we provide evidence on this question by examining associations between consumer confidence during the Great Recession and children's behavior problems. We do so by taking advantage of a unique longitudinal survey, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, which was in the field interviewing 9-year old children and their parents as the Great Recession began, and worsened (2007-2010). Differential timing of interviews within and across the 20 cities in the study provides variation in the level of consumer confidence at the time of the interview. We take advantage of that variation to estimate associations between consumer confidence and child behavior problems as reported by the children and their parents, how those associations vary by child gender and family structure, and the extent to which associations are mediated by parenting behaviors.

Aggregate Shocks and Family Functioning

Our study adds to the growing literature on how an aggregate shock such as the Great Recession might affect children and families. Several studies have found deleterious effects of the Great Recession on parental relationships (Schneider, Harknett, & McLanahan, 2014) and parenting (Berger Fromkin, Stutz, Makoroff, Scribano, Feldman, Tu, & Fabio, 2011; Brooks-Gunn, Schneider, & Waldfogel, 2013; Huang, O'Riordan, Fitzenrider, McDavid, Cohen, & Robinson, 2011; Kalil & Ziol-Guest, 2013; Lee, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, & Garfinkel, 2013; Lindo, Hanson, & Schaller, 2013). This study is among the first to examine the associations between the Great Recession and child outcomes (Leininger & Kalil, 2014). However, researchers have studied associations between other aggregate economic shocks and child outcomes. Two recent studies find negative associations between statewide job loss (due to business and plant closings) and children's school achievement (Ananat, Gassman-Pines, Francis, & Gibson-Davis, 2013) but protective associations for adolescents’ fertility (Ananat, Gassman-Pines, & Gibson-Davis, 2013); in both cases, the authors explore and reject the hypothesis that the associations are limited to those whose parents lost jobs and instead conclude that the effects reflect community-wide uncertainty in the wake of the job losses. Additionally, Ramanathan, Balasubramanian, and Krishnadas (2012) used a similar exogenous shock framework to show that children who were infants during the recessions of the early 1980s were more likely to engage in risky and delinquent behaviors in adolescence than children who did not experience a recession in infancy. Although not tested, the authors propose three possible mechanisms: first, that high unemployment jeopardizes parental investments in children; second, that as described by the family stress model, economic hardship is related to increased parental conflict and stress which decreases parenting quality; and third, that high unemployment negatively alters early parent-child attachment and bonding.

Individual Level Economic Hardship and Family Functioning

The aggregate shocks literature is distinct from, but builds on research that assesses associations between an individual or family's own experience of economic hardship and uncertainty, such as home foreclosure or job loss, and child and family wellbeing. In early work studying families who lost their jobs during the Great Depression (Elder 1974, 1988) and in later work analyzing the effect of economic stress on child wellbeing (Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1992), Conger and Elder proposed an early version of what would become the family stress model. This model was fully articulated in Conger and Elder's (1994) study of the effect of the Iowa Farm Crisis on families. In this work, Conger and Elder documented the ways in which individuals’ and families’ experiences of economic hardship and uncertainty increased parental stress which in turn reduced parents’ warm and supportive interactions with their children, and increased harsh and aggressive parenting (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; Conger & Donellan, 2007; and replicated in other contexts, see Leinonen, Solantaus, & Punamki, 2002 for an example of how economic hardship and job instability during the 1991 recession in Finland affected parenting and marital relationships).

Evidence exists that individual experiences of economic instability and poverty are associated with increased depressive symptoms among parents (Berchick, Gallo, Maralani, & Kasl, 2012), as well as stress (Strully, 2009), and more punitive parenting behaviors (McLoyd, 1990), which in turn are associated with poorer outcomes for children (Yeung, Linver, Brooks-Gunn, 2002).

In recent work, Leininger and Kalil (2014) investigated how the Great Recession was associated with negative outcomes for children living in Michigan. They argue that subjective measures of economic strain may be more salient for child wellbeing than objective measures of unemployment or job loss (see also Kalil, 2013); they further argue that the economic distress experienced by families during the Great Recession was less a result of individual-specific economic experiences than it was a result of uncertainty about the future.

The individual effects literature demonstrates the ways in which economic hardship affects parents and parenting behaviors, which in turn influence child wellbeing. However, potential problems exist with relying on individual measures of economic hardship when estimating associations between the Great Recession and child wellbeing. Foremost among these problems is the potential bias associated with individual level measures of unemployment or economic hardship. For example, an individual's employment or poverty status might be expected to be highly associated with parenting or child wellbeing, for reasons due both to the economic hardship and other possibly unobserved factors associated with it. In contrast, an exogenous measure of the economy, such as consumer confidence, is independent of individuals’ and families’ actual financial experiences. Second, in the aggregate shocks model, parents and children may be affected by an event such as the Great Recession even if an individual parent has not experienced job loss or foreclosure, if the overall economic shock is sufficiently severe and widespread and creates fear and uncertainty on the part of parents, other adults in the children's life, and perhaps the children themselves.1 The Great Recession caused widespread uncertainty and greatly altered people's subjective perceptions of their own and the nation's financial wellbeing. The aggregate shocks model, therefore, may be better able to capture the full extent of the Great Recession.

How Children May be Affected

A robust literature has demonstrated the ways in which environmental and contextual factors can influence children's behaviors and wellbeing. Bronfrenbrenner's (1986) ecological model and Belsky's (1984) process model describe multiple determinants of parenting. In addition, Becker's (1962) theories of human capital, as well as Coleman (1988) and Small's (2004) theories of the ways in which social capital relates to the creation of human capital point toward the importance of environment and social networks in children's healthy development. In addition, links between both family and neighborhood poverty/disadvantage and child outcomes may be exacerbated during times of widespread economic hardship and uncertainty, although there is little literature on this point.

Substantial evidence exists that the developmental stage during which children experience economic hardships and uncertainty may have implications for future wellbeing. The focal children in our sample were approximately 9 years of age during the Great Recession. The extant literature indicates that both young children and young adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to family level factors such as low-income, maternal education, marital status, and parenting (Kalil, 2013; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1999; Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998). In addition to these family level factors, young adolescents’ development is also affected by school and neighborhood environments, peers, and economic opportunity (Kress & Elias, 2006; Leventhal, Dupere, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Rubin, Bulkowski, & Parker, 2006). The children in our study are on the cusp of adolescence.

An aggregate shock such as the Great Recession might affect children both directly and indirectly. Direct effects would occur if children had direct exposure to news accounts about the recession or events associated with it. This would occur if children listened to the news on television or came across news content during their time on the internet or on other media. It is also likely that children would be affected indirectly, through their parents’ exposure (and through the exposure of other adults). Children may have had conversations with their parents or other adults about the Great Recession. The recession may have also altered conversations families had about money or financial matters. Conger and colleagues (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994) have shown that in the face of economic stress, parents and adolescents have increased coercive and hostile exchanges about money. McLoyd and colleagues (1994) demonstrated that children's perceptions of their parents’ economic hardship has a direct association with their own psychological wellbeing. In ethnographic work, Mistry and colleagues (Mistry, Low, Benner & Chien, 2008) have shown that during times of economic hardship and uncertainty mothers and children have discussions about having to cut back on discretionary spending.

If associations are found between the Great Recession and child behavior, it would be important to understand the mechanisms that might help explain them. Theory and prior research suggest that parenting and parental mental health are likely to be important mediating factors. In particular, increased harsh parenting (Brooks-Gunn, Linver, & Fauth, 2005; Conger & Donellan, 2007; Parke, Coltrane, Duffy, Buriel, Dennis, Powers, French, & Widaman, 2004), decreased parental warmth (Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994; Yeung, Linver, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002), and increased maternal depression (Eamon & Zuehl, 2001; McLoyd, Jayaratne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994) have been shown to be primary pathways through which economic distress leads to increases in children's internalizing, externalizing, and other behavior problems. Accordingly, one aim of this study is to investigate the role of parenting as a mediator that might explain associations between the Great Recession and boys’ and girls’ behavior.

McLoyd and colleagues (McLoyd, Jayaratne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994) have shown that in the face of economic hardship and uncertainty, adolescents are affected through changes in parenting behaviors. Specifically, three measures of parenting and parenting behaviors have been shown to be particularly salient. Research from both the family stress literature and from the exogenous shocks literature has shown that economic hardship in the form of both individual level unemployment as well as the aggregate unemployment rate, mass layoffs, and worsening consumer sentiment is associated with increased harsh parenting (Lee, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, Notterman, & Garfinkel, 2013; Brooks-Gunn, Schneider, & Waldfogel, 2013; Lindo, Hanson, & Schaller, 2013) which in turn negatively affects child wellbeing (Conger, Elder, Loren, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1992). Similarly, research has linked economic hardship with maternal depression and diminished warm and supportive parenting. Prior research has shown that economic hardship, maternal depression, and changes in maternal warmth are associated both individually and in combination with children's development (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Elder & Caspi, 1988; Kiernan & Huerta, 2008).

Different Effects by Child Gender

Prior research provides mixed evidence about whether boys and girls are differentially affected by changes in parenting during economic downturns, and the pathways through which differential effects may occur. Using data from the New Hope Project, Mistry and colleagues (2002), for example, did not find any difference between boys’ and girls’ behaviors when their parents experienced economic pressure. In contrast, Elder and his colleagues found that having parents who experienced economic hardship during the Great Depression negatively affected girls’ psychosocial wellbeing (Elder, Van Nguyen, & Caspi, 1985) and that reduced maternal support as a result of economic hardship was related to increased psychological problems among boys, but increased resourcefulness among girls (Elder, 1979). Conger and colleagues (Conger, Conger, Mathews, & Elder, 1999) showed that boys and girls might be affected differently by the direct effect of economic hardship itself (see also Cummings, Vogel, Cummings, & El-Sheikh, 1989, who report that the strongest associations exist between economic hardship and child outcomes for boys compared to girls). However, Conger and colleagues (Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1993), studying families during the Iowa Farm Crisis, also found that increases in parental depression and marital conflict were associated with poorer adjustment for adolescent girls.

This evidence suggests that boys and girls may be differentially affected by changes in parenting. In particular, boys may be more sensitive to parents’ economic distress, and girls may be more sensitive to conflictual parent relations as well as maternal depression. In addition, it is possible that the effects of an economic downturn on parents may vary depending on the gender of their children. One recent study found that mothers of boys experience greater parenting stress in response to economic hardship and uncertainty than mothers of girls (Vierhaus, Lohaus, Schmitz, & Schippmeier, 2013). If this pattern holds, it would provide another reason why boys might be more strongly affected than girls by the Great Recession.

The Moderating Role of Family Structure

Theory and prior research suggest that the effects of a shock such as the Great Recession might vary by family structure. A large literature has demonstrated that children growing up in single-parent families face a wide range of developmental and life course challenges (McLanahan & Sandefeur, 1994; McLoyd, 1990). In addition, research based on the family stress model demonstrates that parental relationships, both the quality of relationships and parents’ marital status, can influence the ways in which economic hardship might affect parenting (McLoyd, 1990). In a review of the literature, Conger and colleagues (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010) reported evidence that children in single-parent families may be at increased risk for behavioral problems in times of economic hardship because economic pressure on single parents may be especially high (Conger & Conger, 2002). Other work has found that financial strain is associated with heightened levels of depressive symptoms among single mothers, resulting in negative effects on parenting (Jackson, Brooks-Gunn, Huang, & Glassman, 2000). In addition, prior research has shown that changes in parenting as a result of economic hardship may particularly affect children living in unstable family environments (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010; McLoyd, Jayaratne, Ceballo, Borquez, 1994). This body of research suggests that the effects of the Great Recession might vary by family structure and in particular might be most negative for children living in single-parent families.

The Present Study

This study estimates the associations between the Great Recession and children's behavior problems, by matching the national Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI) and the local unemployment rate to the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). The pathways between unemployment and health and stress, and negative effects on children, are fairly well established (Berchick, Gallo, Maralani, & Kasl, 2012; Strully, 2009). Recent research on the effect of aggregate shocks on children and families leads us to propose four hypotheses. First, worsening consumer confidence (as measured by the CSI) during the Great Recession will be associated with increased child behavior problems. Second, because prior research has generally found stronger links between economic uncertainty and outcomes for boys than for girls, boys may be more likely to experience problem behaviors as result of the Great Recession than girls (Bolger, Patterson, & Thompson, 1995). Third, because single mothers may be more susceptible to economic hardship and uncertainty, children of single mothers may be more likely to experience increased behavior problems compared with those of married or cohabiting mothers. Fourth, because associations between the Great Recession and children's behavior, if found, may be explained at least in part through mothers’ increased harsh parenting practices, reduced warmth, and increased depressive symptoms, we hypothesize that parenting may at least partially mediate those associations. Controlling for the local unemployment rate will aid in evaluating the robustness of CSI, our primary macro-economic measure. In addition to parenting, changes in household income and employment status may also mediate the association between the Great Recession and children's behavior problems.

Our guiding model then, is one in which economic uncertainty – as measured by the CSI – may increase negative behaviors among children and may potentially be moderated by child gender and family structure. In addition, the association between CSI and problem behaviors may be mediated by parenting, which may itself have changed as result of individual economic stress during the Great Recession.

Methods

Sample

This study draws on data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), a longitudinal birth cohort study made up of 4,898 births in 15 states and 20 U.S cities with populations of 200,000 or more, representing a random sample of births in those cities between 1998 and 2001. This sampling frame accounted for a broad spectrum of the U.S. population, with 59% of the population living in cities of 200,000 or more in 2000 (Census, 2011). FFCWS oversampled non-marital births, which resulted in a sample that is made up of more racial/ethnic minority as well as more low-income and low-education families than a nationally representative sample would be. However when weighted the sample is representative of births in large U.S. cities at that time (Reichman et al., 2001). Follow-up surveys were conducted when the focal child was approximately, 1, 3, 5, and 9 years old, with the 9-year survey consisting of 76 percent of the original sample. The 9-year interviews occurred from August, 2007 to March, 2010, and thus included the period immediately before and during the Great Recession. We also draw on information from the 9-year in-home and child surveys (approximately 69 percent of the original sample) (CRCW, 2011).

Overall, rates of missingness were low (ranging from about 5% to about 12.5%). We use multiple imputation (imputation by chained equations in Stata 13.1) to impute missing information on the covariates. We do not draw on imputed observations for our dependent or lagged dependent variables. The final samples after imputation range from 2,050 to 3,311 (sample sizes vary because of missing outcome variables, which we do not impute. In addition, we do not impute lagged dependent variables, resulting in smaller sample sizes).

After multiple imputation, 52% of children were male, and 21% of mothers were White, 50% African-American, 26% Hispanic, and 3% another race/ethnicity; and 61% of mothers were not married to or cohabiting with the focal child's biological father at the 9-year interview. The imputed sample is similar in make-up to the sample we would have obtained using list-wise deletion. An analysis of baseline characteristics indicates that excluded mothers were more likely to be Hispanic than African-American and slightly more likely to have less than a high school education.

Measures

Child Outcomes

Externalizing

At the 9-year survey mothers were asked a series of questions about their children's externalizing behaviors. These questions were drawn from 35 items making up the aggression and rule-breaking subscales of the Achenbach Child Behavioral Check List (CBCL) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; see also Waldfogel, Craigie, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010 for a discussion of child behaviors in FFCWS). We sum these items creating a scale ranging from 0-70 (9-year, α = 0.83; mean = 6.51, SD = 7.30). At the 5-year survey mothers answered 30 items about the same construct (5-year, α = 0.87; mean = 13.05, SD = 7.68).

Internalizing

Mothers also answered a series of question about their children's internalizing behaviors. These questions were drawn from three subscales of the CBCL focusing on children's anxious/depressed or withdrawn/depressed behaviors, and somatic complaints, consisting of 32 items in total (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). We sum these items creating a scale ranging from 0-64 (9-year, α = 0.88; mean 5.04, SD = 5.96). At the 5-year survey mothers answered 23 items about the same construct (5-year, α = 0.76; mean = 5.34, SD = 4.30).

Drug and alcohol use

One of the unique contributions of this study is our ability to draw on children's reports of their own behaviors at the 9-year survey. Children were asked three questions about their own early drug and alcohol use: whether they had secretly taken a sip of wine, beer, or alcohol; smoked marijuana; or smoked a cigarette or used tobacco. We sum these items and then create a dichotomous variable indicating whether the child had performed any of these behaviors (9-year, α = 0.70; mean = 0.05, SD = 0.21). We create a dichotomized version of this measure because these behaviors are fairly rare. Although rare, this variable represents an important indicator of early drug use.

Vandalism

Children were also asked four questions about their own early vandalism. Items included questions about whether or not the child had: purposely set fire to a building, car, or tried to do so; thrown rocks or bottles at people or cars; purposely damaged or destroyed property; written things or sprayed paint on walls or sidewalks or cars. We sum these items and then create a dichotomous variable indicating whether the child had performed any of these behaviors (9-year, α = 0.70; mean = 0.19, SD = 0.39). Although somewhat rare, this variable represents an important indicator of early vandalism.

Measure of the Great Recession

Consumer Sentiment Index

Consumer confidence is measured using data from the Consumer Sentiment Index (CSI) (Thompson-Reuters/University of Michigan, 2012). CSI data is collected from a national monthly random digit phone survey of a minimum of 500 people and is normalized to have a baseline value of 100 in December, 1964. The CSI captures national opinion about the state of the economy. Prior research has found that worsening confidence as measured by the CSI is associated with increases in property crime, homicide, and felony (Rosenfeld, 2007; Rosenfeld & Fornango, 2007), as well as harsh parenting (Brooks-Gunn; Schneider, & Waldfogel, 2013; Lee, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, Notterman, & Garfinkel, 2013).

CSI data are appended to mother's FFCWS interview date by matching the month and year of mother's interview to the CSI index at that time. In our analysis, CSI is reverse coded so that high values of CSI indicate worse consumer confidence and greater uncertainty. During the period of our study, the CSI (reverse-coded) rose from a low of 55.3 in July 2007 to a high of 90.4 in November 2008, and then declined again to an average of 72.2 through early 2010 (standard deviation = 7.15) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in macro-economic indicators during the Great Recession

Because the CSI is measured at the national level, it captures consumer confidence of the country as a whole in a given month. This is not a problem for our analysis, if we believe that what might matter for child and family well-being is overall uncertainty about the economy. If, however, local variation in uncertainty also matters, then our estimates may suffer from attenuation bias and understate the effect of uncertainty.

The Local Unemployment Rate

We obtain unemployment rate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) and append the data to the FFCWS by matching the monthly local area unemployment rate of the Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA) in which each mother in the Fragile Families data lived at the time of her FFCWS interview. This strategy assigns each mother the unemployment rate from the city in which she was surveyed as part of the age 9 FFCWS. Thus, it is a measure of local labor market conditions (standard deviation = 2.61).

Other Control Variables

The study controls for a number of maternal socio-economic and demographic variables, all measured at the time of the baseline survey (i.e. at the birth of the child) unless otherwise noted, including: maternal age, education (dummy variables for less than high school, high school, some college, college or higher), race/ethnicity (dummy variables for White, African-American, Hispanic, and other), relationship status (dummy variables for married, cohabiting, or not living with a spouse/partner), child sex and age in months (at the 9-year survey); mother's history of depression (between baseline and the 5-year survey); and household income. Models also include controls, when available, for measures of children's prior behaviors at age 5. In addition, city fixed effects (i.e. dummy variable indicators for city of interview) are included in all the models to control for variation across the sample cities (see Appendix 1 for descriptive statistics). Appendix 2 shows the correlations among these variables.

Potential moderator: Family structure

We investigate the potential moderating role of family structure by stratifying our models by whether mothers were currently married/cohabiting or single. We draw on the mother's report at the 9-year interview of whether she is living with or married to the child's biological father or another man, or whether she is single.

Potential moderator: Child gender

We investigate the potential moderating role of child gender by interacting CSI and the unemployment rate with child gender.

Potential mediators: Parenting

In some of our models we also include a number of potential parenting mediators, all measured at the 9-year study. It is important to note that our parenting mediators were measured at the same time as our child outcomes. It is therefore somewhat unclear whether we are capturing a true mediating effect or if for example, child behavior is influencing parenting behavior. As discussed earlier, prior research suggests that children are most likely to be affected by economic downturns through changes in parenting. To that end, we test the role of three aspects of parenting: harsh parenting as measured by maternal physical and psychological aggression; maternal warmth; and maternal depression all measured at the 9-year follow-up.

Harsh parenting

Mothers were asked a series of questions drawn from the Conflict Tactics Scale for Parent and Child (CTPSC) (Strauss, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) which assesses physically and psychologically aggressive parenting behaviors. Mothers were asked 5 questions about how often they spanked, slapped, hit, shook, or pinched their child in the past year (never to more than 20 times). We sum these variables to create a scale ranging from 0 to 27 (α = 0.50). Mothers were asked 5 questions about how often they shouted, cursed, threatened to spank, threatened to kicked their child out of the house, or called their child names in the past year (never to more than 20 times). We sum these variables to create a scale ranging from 0 to 28 (α = 0.77).

Parental warmth

We draw on questions from the HOME scale (Caldwell & Bradley, 2001) to assess maternal warmth. Interviewers recorded whether mothers: (1) spoke to child, (2) used terms of endearment, or (3) cuddled child, among other items. We sum these questions to create a scale ranging from 0 to 7 (α = 0.50).

Maternal depression

We draw on 15 questions designed to assess Major Depressive Episodes (MDE) derived from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Short Form (CIDI-SF) (Kessler et al., 1998; see also DeKlyen, Brooks-Gunn, McLanahan, & Knab, 2006). Mothers were asked about their feelings of dysphoria or anhedonia in the past year that lasted for two weeks or more and if these symptoms occurred every day and for how long. Mothers were coded for depression if they reported two weeks of symptoms that lasted half of the day, almost every day.

Observed harsh parenting

In supplemental analyses we also test the mediating role of maternal harsh parenting that was observed during the in-home visit as part of the 9-year follow survey. Interviewers recorded whether the mother ever: (1) shouted at the child, (2) was openly hostile toward the child, (3) spanked the child, (4) or scolded the child. We create a bivariate indicator of any observed harsh parenting (mean = 0.08).

Potential mediators: Household income & maternal unemployment at 9-year survey

We draw on a measure of mothers’ household income at the 9-year survey to assess the likelihood that household income during the period of Great Recession may mediate the association between our macro-economic indicators and child outcomes. In addition, we draw on a measure of whether the mother was employed in the last week as an indicator of her current employment status.

Analytic Plan

We examine the associations between CSI, the unemployment rate, and four measures of children's behavior problems when they were 9-years old, including two measures of children's behavior (externalizing and internalizing) as assessed by the child's mother (table 1a) and two measures of children's behavior (drug/alcohol use and vandalism) (table 1b) as reported by the child. We estimate the associations between our macro-economic measures and externalizing and internalizing behaviors using OLS regressions and present coefficients from those models. Odds ratios are estimated from logistic regression models for children's self reported drug and alcohol use and vandalism because those measures are dichotomous.

Table 1a.

The Great Recession & Child Internalizing & Externalizing Behaviors, Overall and by Marital Status: Coefficients from OLS Regressiona

| Child Externalizing Behaviors | Child Internalizing Behaviors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Single | Married/Cohabiting | All | Single | Married/Cohabiting | |

| Consumer Sentiment Index | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Local Unemployment Rate | −0.16 | −0.21 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.00 | −0.25 |

| Child male | −3.11 | −9.88+ | 4.47 | −3.62 | −7.37 | 2.96 |

| Child male*CSI | 0.05 | 0.14* | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.11* | −0.06 |

| Child male*UR | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.12 |

| 2053 | 1262 | 791 | 2050 | 1252 | 798 | |

Notes:

p<0.10

p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001

includes city fixed effects, lagged dependent variables and the following covariates: child age, child sex, mother age, household income, mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey), mother race/ethnicity, mother's education level, and mother's marital status.

Table 1b.

The Great Recession & Child Drug/Alcohol Use & Vandalism, Overall and by Marital Status: Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressiona

| Drug/Alc. Use | Vandalism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Single | Married/Cohabiting | All | Single | Married/Cohabiting | |

| Consumer Sentiment Index | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.90 |

| Local Unemployment Rate | 1.03 | 1.27* | 0.69 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.21 |

| Child male | 0.05 | 0.00+ | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.00+ |

| Child male*CSI | 1.05 | 1.14** | 0.97 | 1.07+ | 1.04 | 1.14+ |

| Child male*UR | 1.08 | 0.88 | 1.51 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

| 3143 | 1932 | 1211 | 3311 | 2072 | 1239 | |

Notes:

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

*** p<0.001

includes city fixed effects, lagged dependent variables and the following covariates: child age, child sex, mother age, household income, mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey), mother race/ethnicity, mother's education level, and mother's marital status.

In our externalizing and internalizing behavior models we also include measures of the children's behavior on that scale at the prior wave (at the 5-year survey). This lagged dependent variable model allows us to better assess the change in children's behaviors associated with the Great Recession, holding prior child behavior constant. (We cannot estimate lagged dependent variable models for the drug/alcohol or vandalism outcomes because we do not have data on those outcomes prior to the 9-year survey).

All of our models include the full set of covariates outlined above, as well as city fixed effects. Importantly, we control for the local unemployment rate for the city in which each mother lived. That our results are robust to the inclusion of the unemployment rate adds support for the idea that CSI may operate in a way that is distinct from other macro-economic indicators and may be particularly well-suited to capture the uncertainty associated with the Great Recession. To that end, we will primarily focus on results for CSI but do discuss results related to the local unemployment rate where significant.

We estimate these models for the overall sample and for the sample stratified by family structure, estimating separate models for those children living with single parents and those living with married or cohabiting parents.

To assess differential effects by child gender, we include an interaction term between CSI and child gender and the unemployment rate and child gender. The interaction between the macro-economic indicators and child gender will indicate whether the Great Recession differentially affected boys.

To assess the potential mediating role of parenting, in tables 2a-b, indicators are added for maternal warmth, mother's physical aggression toward the child, mother's psychological aggression, and maternal warmth at year 9 survey. We assess the role of our mediating variables through a type of Sobel test that reduces bias in the decomposition, allows for the simultaneous estimation of multiple mediators, and can be used in both the OLS and logistic regression contexts (KHB – Decomposition) (Breen, Karlson, & Holm, 2011). We also assess the potential mediating role of family income and maternal unemployment at age 9, in a similar way.

Table 2a.

The Great Recession and & Child Internalizing & Externalizing Behaviors and Mediators by Mothers' Marital Status: Coefficients from OLS Regressiona

| Child Internalizing Behaviors | Child Externalizing Behaviors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Married/Cohabiting | Single | Married/Cohabiting | |||||

| Consumer Sentiment Index | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| Local Unemployment Rate | −0.00 | −0.08 | −0.25 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.27 | −0.08 | −0.03 |

| Child male | −7.37 | −5.92 | 2.96 | 0.24 | −9.88+ | −7.06 | 4.47 | 5.07 |

| Child male*CSI | 0.11* | 0.08 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.14* | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Child male*UR | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.22 |

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Warmth | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.21* | −0.26* | ||||

| Physical aggression | 0.07+ | −0.02 | 0.21*** | 0.10 | ||||

| Psychological aggression | 0.20*** | 0.16*** | 0.33*** | 0.27*** | ||||

| Depression | 0.41 | 2.32*** | 1.01* | 1.44* | ||||

| Household Income | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.00 | ||||

| Unemployed | 0.56 | −0.35 | 0.66+ | 0.26 | ||||

| 1252 | 798 | 1262 | 791 | |||||

| Sobel test Z-Score | 1.38+ | n.s. | 1.35+ | n.s. | ||||

Notes:

p<0.10

p<0.05

** p<0.01

p<0.001

includes city fixed effects, lagged dependent variables and the following covariates: child age, child sex, mother age, household income, mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey), mother race/ethnicity, mother's education level, and mother's marital status.

Table 2b.

The Great Recession & Child Drug/Alcohol Use & Vandalism and Mediators by Mothers' Marital Status: Odds Ratios from Logistic Regressiona

| Drug and Alc. Use | Vandalism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Married/Cohabiting | Single | Married/Cohabiting | |||||

| Consumer Sentiment Index | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 0.84+ | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 0.88+ |

| Local Unemployment Rate | 1.27* | 0.95 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.21 | 1.31* |

| Child male | 0.00+ | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.00+ | 0.00+ |

| Child male*CSI | 1.14** | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.14+ | 1.15* |

| Child male*UR | 0.88 | 0.89 | 1.51 | 1.51+ | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Warmth | 1.12 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 0.93 | ||||

| Physical aggression | 0.45* | 0.13 | 0.45* | 0.39 | ||||

| Psychological aggression | 2.18** | 1.52 | 2.18** | 1.38 | ||||

| Depression | 0.79 | 0.19+ | 0.79 | 1.11 | ||||

| Household Income | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00*** | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.37 | 2.14+ | 1.37 | 3.45** | ||||

| 1932 | 1211 | 2072 | 1239 | |||||

| Sobel test Z-Score | 2.84** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

Notes:

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

includes city fixed effects, lagged dependent variables and the following covariates: child age, child sex, mother age, household income, mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey), mother race/ethnicity, mother's education level, and mother's marital status.

It is possible that our results may be biased as a result of shared method variance in so far as mothers report both our mediators and children's internalizing/externalizing behaviors. In supplemental analyses we include a measure of observed maternal harsh parenting. However, observed harsh parenting was quite infrequent. Since this question was missing by design (i.e. it is only present for mothers interviewed in home) it could not be imputed and thus we are left with a large amount of missing data.

Results

Associations between Consumer Confidence during the Great Recession and Children's Behavior Problems

Table 1a shows coefficients from a set of OLS regression models estimating the associations between the macro-economic indicators — the CSI — and children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors as reported by the child's mother. Column 1 shows no significant associations between CSI and children's externalizing behaviors in the full sample. Columns 2 and 3 divide the sample by children who were living with a single mother (col 2) or a married or cohabiting mother (col 3) at the 9-year survey. The interaction between CSI and boys in column 2 indicates that worsening CSI is associated with a significant increase in externalizing behavior for boys living with a single mother (coeff. 0.14, p < 0.05). In contrast, the interaction between CSI and boys is not significant for children living with a married or cohabiting mother. Columns 4-6 show a similar pattern, with the interaction between CSI and boys not significant for all mothers overall or for married or cohabiting mothers. However, the interaction between CSI and boys in column 5 indicates that worsening CSI is associated with a significant increase in internalizing behaviors among boys living with a single mother (coeff. 0..11, p <0.05).

Table 1b shows odds ratios from a set of logistic regression models estimating the associations between CSI and children's self-reported drug and alcohol use and vandalism. Column 1 shows no association between CSI and children's drug and alcohol use in the full sample. Columns 2 and 3 again divide the sample by children who were living a single mother (col 2) or a married or cohabiting mother (col 3). The interaction between CSI and boys in column 2 indicates that worsening CSI is associated with a significant increase in the odds of drug and alcohol use for boys living with a single mother (odds ratio: 1.14, p < 0.01). There is no significant association for children living with a married or cohabiting mother. Columns 4-6 show results for self-reported vandalism among children. The interaction between CSI and boys in columns 4 and 6 indicates that worsening CSI is associated with a marginally significant increase in the odds of vandalism among boys in households overall (odds ratios: 1.07, p < 0.10) and among boys living with a married or cohabiting mother (odds ratio: 1.14, p < 0.10).

The Role of Parenting, Household Income and Maternal Unemployment as Potential Mediators

Tables 2a and 2b examine the role of a series of potential mediators within the context of family structure (i.e. in models stratified by family structure). These models allow us to explore the possible mechanisms that might underlie the generally strong interactions found for boys in single-parent families versus married/cohabiting families. In particular, we examine the role of parenting as well as household income and maternal unemployment at the age 9 survey.

Model 1 repeats the analysis from table 1a. Model 2 demonstrates that, for externalizing behaviors, the addition of maternal warmth, physical aggression, depression, psychological aggression, household income, and maternal unemployment significantly mediates the interaction between CSI and boys (coeff. 0.10, n.s.) for children living with a single mother (Sobel test of mediation z score = 1.35, p <0.10). However, the addition of the measures of parenting does not influence the interaction between CSI and boys for those living with a married or cohabiting mother.

Turning to children's internalizing behaviors, model 1 again repeats the analysis from table 1a. Model 2 demonstrates that, for internalizing behaviors, the addition of our measures of parenting, household income, and maternal unemployment significantly mediates the interaction between CSI and boys (coeff. 0.08, n.s) for children living with a single mother (Sobel test of mediation z score = 1.38, p <0.10). However, the addition of our measures of parenting does not influence the interaction between CSI and boys for those living with a married or cohabiting mother.

Table 2b re-estimates the analyses for children's self-reported drug and alcohol use and vandalism. Model 1 repeats the analysis from table 1b. Model 2 demonstrates that, for drug and alcohol use, the addition of our measures of parenting, household income, and maternal unemployment significantly mediates the interaction between CSI and boys (odds ratio: 1.05, n.s) for children living with a single mother (Sobel test of mediation z score = 2.84, p <0.01). The addition of our parenting mediators results in the interaction between the unemployment rate and boys becoming marginally significant (odds ration 1.51, p < 0.10) among those living with a married or cohabiting mother. The parenting measures do not mediate the interaction between CSI and boys for any of the sub-groups of vandalism examined. We have shown estimates for two aspects of child self-reported early delinquency. It is important to note that we tested the full scale, including two additional measures of child self-reported stealing and cheating at school, and the results were not significant.

In appendix III we test the possible mediating role of observed harsh parenting. However, these results are limited because of the nature of the observed harsh parenting measures. Column 1 under single mother and externalizing demonstrates a similarly sized, though non-significant, coefficient for the interaction between CSI and boy as the findings from our main model. The addition of our parenting, income, and unemployment measures in model 2 reduces the magnitude of the interaction between CSI and boy, but the coefficient remains non-significant. However, the coefficient for observed harsh parenting is large and significant. The interaction between CSI and boy is not significant for children living with a married or cohabiting mother, nor is the coefficient for observed harsh parenting.

Turning to children's internalizing behaviors we find a similar pattern of results. The interaction between CSI and boys in model 1 indicates that worsening CSI is associated with a marginally significant increase in externalizing behavior for boys living with a single mother (coeff. 0.13, p < 0.10). The addition of our parenting mediators reduces the interaction coefficient (coeff. 0.11, n.s.). However, the coefficient for observed harsh parenting is not significant. We do not find any significant associations among children living with a married or cohabiting mother. That the addition of observed harsh parenting as a potential mediator does not appear to alter the magnitude of our findings may indicate that shared method variance is not substantially biasing our results.

Discussion

A wide range of prior research has established that children are likely to be negatively affected by their families’ actual experiences of economic hardship through changes in parental relationships and parenting (Conger & Donellan, 2007; McLoyd, 1998; Weiland & Yoshikawa, 2012). Although a robust literature has investigated the ways in which individual and family level economic hardship affects children (e.g. see: Parke, Coltrane, Duffy, Buriel, Dennis, Powers, French, & Widaman, 2004; Solantaus, Leininen, & Punamaki, 2004), a limited body of work has examined how aggregate shocks to the macro-economy itself may affect parents and children, and to our knowledge no study to date has examined the possible associations between the macro-economic changes of the Great Recession and child behavior problems.

Prior research on the effects of individual and family level economic hardship on children has found that: (1) boys and girls may be affected differently; (2) changes in parenting are likely to be a primary pathway through which children are affected; and (3) economic hardship may also have direct effects on children (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Examining a macro-level (rather than individual or family level) shock, our study provides evidence of similar processes. We find that boys and girls were differentially affected by the Great Recession, that parenting played a role, and that there were also some direct effects. We also find that children in single-parent families were most strongly affected, a novel finding that may reflect the fact that this is the first study of such processes to include a large sample of single-parent families.

Because our models for children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors also controlled for lagged dependent variables which measured these behaviors at the prior wave, we view these findings as estimates of changes in children's behavior linked to the Great Recession. First, we find evidence that boys’ behaviors changed as a result of the Great Recession. For example, we find significant interactions indicating that boys displayed more externalizing and internalizing behaviors as CSI worsened. We also find that boys facing worse CSI had increased odds of self-reported vandalism and use of drugs and alcohol. We do not have prior measures of these behaviors for our sample, but given the young age of these children we would assume these behaviors represent an increased risk of entry into these behaviors for boys associated with worsening consumer confidence. Our findings are largely consistent with some prior research indicating that boys may be more strongly affected by economic hardship and uncertainty than girls.

We add to this literature by demonstrating that the differential effects of the Great Recession on boys and girls are not wholly driven by the different ways that they are parented, or by the different ways that they react to their parents, but rather that boys and girls may be differently affected by the direct effect of the Great Recession itself (as measured by CSI). However, it is also possible that other aspects of parenting that we are not able to measure may differentially affect them, or that parents may change parenting as a result of differential behavior changes in boys and girls. Importantly, we find associations between the interaction between CSI and boys for our child outcomes, but largely do not find evidence of the effect of the unemployment rate (with the exception of the finding noted above regarding alcohol/drug use for girls). This may indicate that the uncertainty associated with the Great Recession (as captured by the CSI) is particularly important for child wellbeing.

Moderators

The existing research, testing the family stress model at the individual and family level, has generally been applied in households where two parents are present and explores the relationships between mother, father, and children. Our results, from analyses looking separately at single vs. married/cohabiting parents, provide evidence that family structure may play a moderating role in how children are affected by economic hardship and uncertainty. We find that boys’ increased externalizing and internalizing, and drug and alcohol use, are moderated by family structure. The interaction between worsening CSI and boys is associated with increased problem behaviors among those living with single mothers, but not for those living with married/cohabiting mothers, with the exception of self-reported vandalism. We can only speculate as to the reason for this finding. It is possible that married and cohabiting mothers may have more stability and confidence in their home lives, which may buffer some of the uncertainty they face in the larger economy. It may also be that married and cohabiting mothers have more social support, which might also moderate some of the effects of uncertainty about the economy. The individual effects literature has looked to the conflict between spouses as a primary pathway through which children are negatively affected by economic hardship (Elder, 1974) while the exogenous shock literature has largely focused on direct effects of the macro-economy on wellbeing. Our findings highlight the need for further study into the ways in which uncertainty about the macro-economy may differentially affect children by marital status, and how those processes might vary by the child's gender.

Mediators

Our mediation analysis results indicate that some of the association between worse CSI and boys’ problem behaviors may work through maternal parenting. Our results show that when parenting behaviors, household income, and maternal unemployment are added as a group they significantly reduce the interaction between CSI and boys for externalizing and internalizing among those living with a single mother. Specifically, maternal warmth, physical and psychological aggression, depression, and unemployment are significant and mediate the interaction between CSI and boys living with a single mother by approximately 27%. Similarly, mothers’ psychological aggression significantly mediates the interaction between CSI and boys for internalizing behaviors among those living with a single mother by approximately 29%. In addition, we find that mothers’ physical and psychological aggression significantly mediates the interaction between CSI and boys for child self-reported drug and alcohol use among those living with a single mother by approximately 36%. Importantly, household income and maternal unemployment at the 9-year survey largely do not mediate the interaction between CSI and boys for externalizing and internalizing behaviors. This result suggests that single mothers alter their parenting practices when faced with perceived economic uncertainty, and that these changes in parenting affect boys’ behavior.

We find evidence that the Great Recession had some direct associations with children's behavior problems. This finding is consistent with existing literature, which indicates that in addition to mediated effects through parenting, economic hardship can have direct effects on children's behaviors (see Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, 2012 for a review). The differential findings by gender are consistent with some evidence that boys may be more vulnerable to direct effects of economic hardship than girls who may be more responsive to changes in parenting that are a result of economic pressure (Cummings, Vogel, Cummings, & El-Sheikh; McLoyd, 1989).

That we find evidence of direct effects of the Great Recession on children's behaviors when using our macro-level CSI indicator rather than individual or family level economic hardship is an important contribution. The CSI is a measure of the uncertainty that the country's population feels about their own and the nation's financial wellbeing. The CSI captures the uncertainty not only of those who were affected by the Great Recession through individual or family level factors such as unemployment or foreclosure but also those who simply felt unsure of their financial future. Indeed, theories about subjective wellbeing (Deaton, 2012) indicate that people often over-estimate their own vulnerability to negative circumstances. In fact, Kalil (2013) has argued that many of the measures of economic hardship in the individual effects literature are in fact subjective measures of “financial stress.” In terms of what would explain the direct effects of CSI that we find, it is possible that the children in our study themselves responded to the real or perceived financial insecurity of their families, or to the heightened anxiety felt in the general public through media, friends, and school. It is also possible that there is some unmeasured pathway that would fully mediate this association. For example, individual economic strain might be one such pathway; unfortunately we do not have a measure of economic strain in our data. However, our results suggest that a direct association between the Great Recession and child behavior exists.

Limitations

This study encountered five primary limitations. First, in common with all observational studies, we cannot be certain that the associations we are estimating are causal. However, because the Consumer Sentiment Index is exogenous to the individual, the Great Recession can be seen as a “natural experiment” and thus unlikely to be confounded with unobserved individual factors. In addition, our models include extensive controls for child and family characteristics, city fixed effects, and, in some models, lagged dependent variables. Second, because the measures of parenting and of children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors are both reported by the mother, there is the possibility of shared method variance. However, the results are similar for children's self reported vandalism and drug and alcohol use, which indicates that this may not be an issue. Third, CSI is measured at the national level and it is possible that it loses some geographic variation in the severity of the Great Recession by region. If this is the case, then possibly our results may suffer from attenuation bias and hence would understate the effects of the Great Recession. Fourth, our observed measure of maternal warmth has a moderate reliability coefficient (α = 0.50). Because of the difficulties involved in collecting data across 20 cities, we were unable to collect videotaped parent-child interactions to measure warmth as done, for example, in the Iowa Youth and Families Project (Elder & Conger, 2000), but instead must rely on interviewer observations. In addition our measure of warmth, drawn from the HOME scale, is highly skewed by design (−0.72) meaning that most parents score on the high end of the warmth scale (Bradley, 2004). Fifth, because our parenting measures were assessed at the same time as our child behavior outcomes it is possible that parenting may have been influenced by child behavior, rather acting as a true mediator of our child outcomes.

Conclusion

This study provides new evidence about associations between the Great Recession and children's problem behaviors. Perhaps most importantly, the study provides evidence that boys and girls may react differently to an aggregate shock such as the Great Recession, with boys increasing problem behaviors but not girls. In addition, we find that boys living with single-mothers may be at particular risk during economic downturns, perhaps because of the increased instability or lack of support faced by these families, and with these associations explained at least in part by changes in their mothers’ parenting.

This work also provides evidence about the role of aggregate economic shocks versus individual or family level economic hardship. We drew on the Consumer Sentiment Index because it is a macro-level indicator of economic uncertainty. Using this macro-level measure offers two important benefits. First, it avoids the potential bias associated with individual level unemployment. Much of the prior evidence about the pathways through which economic uncertainty affects children looks to parental unemployment. However, individual level employment status may be correlated with a range of parenting and child behaviors while macro-level measures of the economy are not. Second, because the Great Recession had diffuse effects across multiple sectors of the economy and caused high levels of uncertainty even among those who did not become unemployed, CSI (a measure of uncertainty about the economy), may be a more appropriate measure of the extent to which people were affected by the Great Recession than individual level economic hardship.

Appendix

Appendix I.

Descriptive Statisticsa

| Mean | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Child's age (in months at 9-year survey) | 112.52 | 0.08 |

| Child gender (male) | 0.52 | 0.01 |

| Mother's age | 25.05 | 0.11 |

| Household income (4) | 32,036.59 | 562.08 |

| Mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey) | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Mother race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| African-American | 0.50 | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Mother's education | ||

| Less than high school | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| High school or equivalent | 0.32 | 0.01 |

| Some college | 0.25 | 0.01 |

| College or higher | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Mother's marital status (baseline) | ||

| Married | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| Cohabiting | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Single | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| Mother's marital status (9-year survey) | ||

| Married | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Cohabiting | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Single | 0.61 | 0.01 |

| Mother's parenting (9-year survey) | ||

| Warmth | 4.83 | 0.04 |

| Physical aggression | 3.57 | 0.08 |

| Psychological aggression | 7.22 | 0.10 |

| Depression | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| Household income ($) (9-year survey) | 44,600.93 | 879.72 |

| Unemployed (9-year survey) | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| N | 3,311 | |

Notes:

all covariates measured at baseline unless otherwise noted

Multiply imputed data

Appendix 2.

Correlation among study variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing | Internalizing | Drug/Alc. | Vandalism | CSI | Unemployment rate |

Girl | HH Income (Baseline) |

HH Income (Yr. 9) |

Mother age | Child age | |

| (1) | - | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (2) | 0.6505*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (3) | 0.0996** | 0.017 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (4) | 0.1995*** | 0.0702 | 0.1553*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (5) | 0.002 | −0.0562 | 0.0303 | 0.0756 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (6) | −0.0317 | −0.0386 | 0.0174 | 0.008 | 0.0009 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (7) | −0.1034*** | −0.0159 | −0.0298 | −0.1364*** | −0.0008 | 0.0171 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (8) | −0.1068*** | −0.0678 | −0.0227 | −0.0828+ | 0.0296 | 0.0558 | 0.0019 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (9) | −0.1285*** | −0.0762 | −0.0301 | −0.0621 | 0.006 | −0.018 | −0.0243 | 0.5724*** | -- | -- | -- |

| (10) | −0.1096*** | −0.028 | −0.0429 | −0.0834* | 0.0027 | 0.0081 | −0.0112 | 0.3496*** | 0.3055*** | -- | -- |

| (11) | −0.0255 | 0.0283 | −0.0365 | −0.0138 | −0.3240*** | 0.0238 | 0.031 | −0.1025*** | −0.0646 | −0.062 | -- |

| (12) | 0.025 | 0.0072 | −0.0075 | −0.0535 | −0.0084 | 0.033 | −0.0039 | 0.3542*** | 0.3275*** | 0.2151*** | −0.1006** |

| (13) | 0.0197 | −0.079 | 0.036 | 0.1497*** | 0.1869*** | −0.1313*** | 0.0102 | −0.2645*** | −0.2513*** | −0.1476*** | −0.0551 |

| (14) | −0.046 | 0.076 | −0.0488 | −0.1095*** | −0.2061*** | 0.0925*** | −0.0083 | −0.0792 | −0.0728 | −0.0584 | 0.1437*** |

| (15) | −0.0016 | 0.0193 | 0.0346 | −0.0277 | −0.0028 | 0.065 | 0.0007 | 0.1061*** | 0.1158*** | 0.0532 | 0.0388 |

| (16) | −0.1097*** | −0.0526 | −0.0261 | −0.0632 | 0.0388 | −0.0135 | −0.0357 | 0.4933*** | 0.4526*** | 0.4069*** | −0.0406 |

| (71) | 0.0088 | 0.0236 | −0.0242 | −0.0075 | −0.0795+ | 0.0104 | 0.048 | −0.1454*** | −0.1387*** | −0.1334*** | 0.0489 |

| (18) | 0.0880*** | 0.0234 | 0.0463 | 0.0628 | 0.0427 | 0.0018 | −0.015 | −0.2935*** | −0.2642*** | −0.2291*** | −0.0114 |

| (19) | 0.0514 | 0.0676 | 0.0063 | 0.0409 | −0.0685 | 0.0232 | −0.0128 | −0.2601*** | −0.2668*** | −0.2811*** | 0.1098*** |

| (20) | 0.0484 | −0.004 | 0.0158 | 0.0152 | 0.0658 | −0.0492 | 0.01 | −0.1965*** | −0.1523*** | −0.1006** | 0.0005 |

| (21) | −0.049 | −0.0576 | −0.0099 | −0.0107 | −0.0005 | 0.0549 | 0.0273 | 0.0700 | 0.0507 | 0.0817+ | −0.0545 |

| (22) | −0.0712 | −0.0097 | −0.0172 | −0.0619 | 0.0026 | −0.036 | −0.0325 | 0.5283*** | 0.5020*** | 0.4093*** | −0.0767 |

| (23) | −0.0701 | −0.0338 | −0.0312 | −0.0438 | −0.0552 | −0.0774 | 0.0278 | 0.0841* | 0.0641 | 0.0860* | 0.02 |

| (24) | 0.3005*** | 0.1341*** | 0.0884* | 0.1243*** | 0.0696 | −0.0444 | −0.0655 | −0.1040*** | −0.1081*** | −0.1358*** | −0.0737 |

| (25) | 0.3827*** | 0.2014*** | 0.0817 | 0.1265*** | 0.0624 | −0.0385 | −0.0675 | −0.0311 | −0.0528 | −0.1154*** | −0.068 |

| (26) | 0.1789*** | 0.1757*** | 0.0223 | 0.0842* | −0.0101 | −0.0144 | 0.0035 | −0.0624 | −0.0925** | −0.0704 | 0.0203 |

| (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | (22) | (23) | (24) | (25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | African American |

Hispanic | Other race/ ethnicity |

Married | Cohabiting | Single | Less than HS |

HS | Some college |

College or more |

Warmth | Physical Aggression |

Psych. Aggression |

|

| (13) | −0.5261*** | -- | ||||||||||||

| (14) | −0.3102*** | −0.5704*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (15) | −0.1006** | −0.1849*** | −0.1091*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (16) | 0.3298*** | −0.2748*** | −0.0348 | 0.0844* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (71) | −0.0805+ | −0.0332 | 0.1392*** | −0.0568 | −0.4162*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (18) | −0.2123*** | 0.2739*** | −0.1039*** | −0.0194 | −0.4775*** | −0.6001*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (19) | −0.1627*** | −0.012 | 0.1853*** | −0.037 | −0.2178*** | 0.1028*** | 0.0923** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (20) | −0.0930** | 0.1239*** | −0.047 | −0.016 | −0.1645*** | 0.056 | 0.0906* | −0.4283*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (21) | 0.0185 | 0.0376 | −0.0486 | −0.0296 | 0.0214 | 0.0002 | −0.019 | −0.3877*** | −0.408*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (22) | 0.3227*** | −0.2038*** | −0.1209*** | 0.1108*** | 0.4914*** | −0.2158*** | −0.224*** | −0.2469*** | −0.260*** | −0.234*** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| (23) | 0.1103*** | −0.0238 | −0.0911* | 0.0306 | 0.047 | −0.003 | −0.0385 | −0.0951** | −0.0171 | 0.0522 | 0.0829 | -- | -- | -- |

| (24) | −0.1360*** | 0.1998*** | −0.0896* | −0.0242 | −0.0844* | −0.0055 | 0.0795 | −0.0286 | 0.0850* | 0.0093 | −0.0906* | −0.0214 | -- | -- |

| (25) | −0.0085 | 0.1174*** | −0.1283*** | 0.0029 | −0.0638 | −0.0046 | 0.0606 | −0.0464 | 0.0449 | 0.0338 | −0.0438 | 0.0117 | 0.6107*** | -- |

| (26) | 0.0147 | 0.0126 | −0.0185 | −0.0239 | −0.0832 | 0.0606 | 0.0147 | 0.1011** | −0.0159 | −0.033 | −0.0709 | −0.0242 | 0.1122*** | 0.1829*** |

p<0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Appendix III.

The Great Recession and & Child Internalizing & Externalizing Behaviors and Mediators by Mothers' Marital Status: Coefficients from OLS Regressiona,b

| Child Externalizing Behaviors | Child Internalizing Behaviors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Married/Cohabiting | Single | Married/Cohabiting | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Consumer Sentiment Index | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Local Unemployment Rate | −0.27 | −0.34 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.02 |

| Child male | −8.64 | 6.224 | 5.26 | 6.62 | −10.11 | −9.15 | 2.93 | 3.58 |

| Child male*CSI | 0.12 | 0.09 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.13+ | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| Child male*UR | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.04 |

| Mediators | ||||||||

| Warmth | −0.22+ | −0.24* | −0.06 | −0.09 | ||||

| Observed harsh parenting | 2.40*** | 0.72 | 0.37 | −0.29 | ||||

| Physical aggression | 0.19*** | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.04 | ||||

| Psychological aggression | 0.29*** | 0.27*** | 0.14*** | 0.16*** | ||||

| Depression | 1.65** | 1.25* | 1.01* | 1.96*** | ||||

| Household Income | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.02* | 0.00 | ||||

| Unemployed | −0.06 | 0.36 | 0.20 | −0.08 | ||||

| 1050 | 698 | 1028 | 703 | |||||

Notes:

p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

includes city fixed effects, lagged dependent variables and the following covariates: child age, child sex, mother age, household income, mother ever depressed (baseline to 5-year survey), mother race/ethnicity, mother's education level, and mother's marital status.

models restricted to non-missing for observed parenting at the age nine follow-up survey

Footnotes

9/11 provides another example of a stressor that has been studied from both aggregate shock and individual effects perspectives. Studies on the aggregate effects of 9/11 confirm that the effects of 9/11 on outcomes such as parenting quality or family stress are not limited to those who were directly affected by the attacks or who lived in the immediate area; rather, their results suggest that the fear and uncertainty associated with an event like 9/11 can and do affect family functioning even among those not directly affected (see e.g. Gershoff et al., 2010).

Contributor Information

William Schneider, Columbia University, School of Social Work.

Jane Waldfogel, Columbia University, School of Social Work, jw205@columbia.edu.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Columbia University, Teacher's College, jb224@columbia.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anat B, Jamison J. Communities & Banking. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; 2012. 2013. The Great Recession and confidence in homeownership. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- Ananat EO, Gassman-Pines A, Francis DV, Gibson-Davis CM. Children left behind: The effects of statewide job losses on student achievement. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2011 working paper no. 17104. [Google Scholar]

- Ananat EO, Gassman-Pines A, Gibson-Davis CM. The effect of local job loss on teenage birthrates: Evidence from North Carolina. Demography. 2013;50(6):2151–2171. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Allem J-P, Childers MA, Zafar W, Latkin C, Ribisi KM, Brownstein JS. Novel surveillance of psychological distress during the Great Recession. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;142(1-3):323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Political Economy. 1962;70(5):9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55(1):83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchick ER, Gallo WT, Maralani V, Kasl SV. Inequality and the association between involuntary job loss and depressive symptoms. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;75(10):1891–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RP, Fromkin JB, Stutz H, Makoroff K, Scribano PV, Feldman K, Tu LC, Fabio A. Abusive Head Trauma During a Time of Increased Unemployment: A Multicenter Analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):637–643. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Thompson WW. Psychosocial adjustment among children experiencing persistent and intermittent family economic hardship. Child Development. 1995;66:1107–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH. Chaos, culture, and covariance structures: A dynamic systems view of children's experiences at home. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4(2/3):243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Breen R, Karlson KB, Holm A. Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models.”. Sociological Methods & Research. 2013;42(2):164–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfrenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(6):723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Schneider W, Waldfogel J. The Great Recession and the risk for child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(10):721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology. 1993;99(2):353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Linver MR, Fauth RC. Children's competence and socioeconomic status in the family and neighborhood. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, editors. Handbook of competence and motivation. The Guilford Press; New York: 2005. pp. 414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. HOME inventory and administration manual. 3 ed. University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and University of Arkansas at Little Rock; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [10/20/14];Census 2000 Population Statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/census_issues/archives/metropolitan_planning/cps2k.c fm.

- Center for Research on Child Wellbeing . Princeton University; [02/18/15]. Retrieved from: www.crcw.princeton.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Matthews LS, Elder GH. Pathways of economic influence on adolescent adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:519–541. doi: 10.1023/A:1022133228206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2002;64(2):361–73. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr. Families in troubled times: The Iowa Youth and Families Project. In: Conger RD, Elder GH Jr, editors. Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. Aldine; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Jr., Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65(2):541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr., Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;(63):526–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr., Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:206–19. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Matthews LS, Elder GH., Jr. Pathways of economic influence on adolescent adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:519–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1022133228206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Vogel D, Cummings JS, El-Sheikh M. Children's responses to different forms of expression of anger between adults. Child Development. 1989;60(6):1392–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton A. The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans. Oxford Economic Papers. 2012;64(1):1–26. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpr051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen M, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S, Knab J. The mental health of married, cohabiting, and non–coresident parents with infants. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1836–1841. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. The Consequences of Growing Up Poor. The Russell Sage Foundation; New York: NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63(3):406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK, Zuehl RM. Maternal depression and physical punishment as mediators of the effect of poverty on socioemotional problems of children in single-mother families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(2):218–226. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr. Children of the Great Depression: Social Changes in Life Experience. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1974. [Google Scholar]