Abstract

Diabetes self-care is a critical aspect of disease management for adults with diabetes. Since family members can play a vital role in a patient’s disease management, involving them in self-care interventions may positively influence patients’ diabetes outcomes. We systematically reviewed family-based interventions for adults with diabetes published from 1994 to 2014 and assessed their impact on patients’ diabetes outcomes and the extent of family involvement. We found 26 studies describing family-based diabetes interventions for adults. Interventions were conducted across a range of patient populations and settings. The degree of family involvement varied across studies. We found evidence for improvement in patients’ self-efficacy, perceived social support, diabetes knowledge, and diabetes self-care across the studies. Owing to the heterogeneity of the study designs, types of interventions, reporting of outcomes, and family involvement, it is difficult to determine how family participation in diabetes interventions may affect patients’ clinical outcomes. Future studies should clearly describe the role of family in the intervention, assess quality and extent of family participation, and compare patient outcomes with and without family involvement.

Keywords: family-based, diabetes, self-management

Background

The burden of diabetes

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over 29 million adults in the United States are living with diabetes.1 In 2012 alone, 1.7 million adults were newly diagnosed with diabetes.1 People with diabetes are at risk for numerous complications, including diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, amputations, and premature death.1 The management of diabetes can be relatively complex for patients. They must attend multiple physician visits per year; adhere to several different types of medications to control their disease; participate in many facets of self-care, including home glucose monitoring, healthy eating, and exercise; and negotiate barriers to management, such as cost of care and balancing work and life commitments.2

Importance of family in diabetes self-care

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a critical component of care for all individuals with diabetes.2 For adults with type 2 diabetes, engaging in diabetes self-care activities is associated with improved glycemic control and can prevent diabetes-related complications.2–5 Much of a patient’s diabetes management takes place within their family and social environment.6 Addressing the family environment for adults with diabetes is important since this is the context in which the majority of disease management occurs. The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care defines family members as two or more persons who are related in any way—biologically, legally, or emotionally.7 Thus, family members can include nuclear, extended, and kinship network members.8

Family members can actively support and care for patients with diabetes.9 Most individuals live within a household that has a great influence on diabetes-management behaviors.10 A study of more than 5000 adults with diabetes highlighted the importance of family, friends and colleagues in improving well-being and self-management.11 Family members are often asked to share in the responsibility of disease management. They can provide many forms of support, such as instrumental support in driving patients to appointments or helping inject insulin, and social and emotional support in helping patients cope with their disease.12–13 Through their communications and attitudes, family members often have a significant impact on a patient’s psychological well-being, decision to follow recommendations for medical treatment, and ability to initiate and maintain changes in diet and exercise.14 Among middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes, social support has been found to be associated with improved self-reported health in long-term follow-up.15 Family cohesion and family functioning have also been found to be positively related to patients’ self-care behaviors and to improvements in blood glucose control.16–19

Providing diabetes education to just the individual with type 2 diabetes could limit its impact on patients, since family may play such a large role in disease management. Family-based approaches to chronic disease management emphasize the context in which the disease occurs, including the family’s physical environment, as well as the educational, relational, and personal needs of patients and family members.12,20 Including family members in educational interventions may provide support to patients with diabetes, help to develop healthy family behaviors, and promote diabetes self-management.21

The negative ways family can affect diabetes

Patients’ family and friends can provide support in overcoming barriers in executing diabetes self-management, but behaviors of family members also have the potential to be harmful.22 How the family is structured and its beliefs and problem-solving skills or lack thereof can exacerbate the stresses associated with disease management.12 The lifestyle changes required for optimal diabetes self-management often conflict with established family routines.23 Self-management tasks may necessitate changing the types of food prepared and consumed in the home, time away from work for the family member to attend medical visits with the patient, and reprioritization of family finances, all which may affect family routines. Since family members participate in purchasing groceries, creating family schedules, and cooking meals, they can help or hinder necessary lifestyle changes for people with diabetes.22 In studies of adults with type 2 diabetes, participants have reported that family members’ nonsupportive behaviors were associated with being less adherent to one’s diabetes medication regimen and with having poorer glucose control.24–26 Family members may sabotage or undermine patients’ self-care efforts by planning unhealthy meals, tempting patients to eat unhealthy foods, or questioning the need for medications.25,27 Family members may also nag or argue with patients in an attempt to support adherence.25,28 One study found that pressure from a spouse regarding a patient’s diet is associated with higher diabetes-specific distress among adults with type 2 diabetes.29 A family’s obstructive behaviors may be more harmful among adults with limited health literacy and patients who are experiencing other stressors or major depressive symptoms.26,30 Hence, diabetes self-management interventions should focus not only on the individual patient, but also on the family, so that they are better equipped to positively support their loved one with diabetes.25

Supporting family

Diabetes self-management interventions may need to place greater emphasis on targeting family members’ communication skills and teaching them positive ways to influence patient health behaviors.31 Family members can feel distressed by their loved one’s diabetes28,32–34 due to limited knowledge about diabetes or not knowing how to support their loved one.12,27,35–37 Family may also have misconceptions, such as believing the patient knows more about diabetes than the patient actually reports or not understanding their loved one’s needs in diabetes management.27,38 Knowledge about the disease, strategies to alter family routines, and optimal ways to cope with the emotional aspects of the disease are some of the aspects of diabetes self-management that family members need.39 Educating family members about diabetes-care needs can help ease this strain by explaining why these changes are necessary, how these changes can best be implemented, and where to find additional information, such as healthy recipes or exercise routines.24 Effective family management can also reduce the strain that family members may experience when coping with altered lifestyles and disease progression.24 It is important to provide family members with information about the illness and possible treatment options, validate their experiences as providers of support, teach them various stress management skills, and help them plan for the future.31

Influencing family member outcomes

Carefully designed studies are needed to evaluate the benefits of diabetes self-management interventions for both the patient and the family member.40 How families manage chronic disease affects not only the patient’s health, but the health of others in the family as well.12 Assessing family members’ knowledge in diabetes self-care and perceived ability to support their loved one with diabetes may be important end points for diabetes self-care interventions. Family members may also benefit more directly by reducing their own psychological distress regarding their loved one’s diabetes and by improving their own health behaviors through attending health education programs.32,41,42 Furthermore, family members at high risk for diabetes may decrease their own likelihood of developing diabetes through improved lifestyle behaviors and weight loss. In a review of randomized controlled trials of chronic disease interventions, benefits for family members were rarely assessed.40

Importance of culture

The importance of family involvement in diabetes self-management has been demonstrated across patients from various racial and ethnic minority populations.43–45 A systematic review of DSME interventions among older adults with diabetes from ethnic minorities found that characteristics of successful interventions included involvement of spouses and adult children.44 In another study among African-American women with diabetes, many women noted that support primarily came from family.27 In a study of Korean immigrants with type 2 diabetes, family support specific to diet was significantly associated with better glucose control.43 In American Indian populations, active family nutritional support was significantly associated with control of triglyceride, cholesterol, and A1c levels.46,47 Furthermore, among many Latinos, familismo, the importance of family and family-centeredness, is an important cultural value.8 Tailoring clinical care and developing novel educational approaches that include family and community is central to improving the health of Latinos with diabetes.8 Studies of Latinos with diabetes have found that including family members in educational interventions may promote patients’ diabetes self-management.21,48,49 Understanding a patient’s cultural and family environment is important in supporting diabetes self-care and in considering how to culturally tailor interventions for patients from racial/ethnic minority populations.

Including family members in diabetes interventions

Recognition of the important role that family members play has led increasingly to incorporating the index patient’s family members into diabetes self-management interventions.50 Family members play an especially significant role in managing diabetes for children and adolescents; thus, most family-based interventions to date have targeted children with diabetes.20,51,52 A review of family-based interventions for patients with diabetes mellitus conducted in 2005 found that most family interventions for diabetes in the previous 15 years were among youth and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, but few studies had focused on adult patients and their family members.20

Among adults, inclusion of a close family member in psychosocial interventions for chronic conditions may also be more efficacious than focusing solely on the patient.40 For example, including family members in educational interventions has been shown to improve rates of smoking cessation53,54 and weight loss.55,56 In a review of randomized controlled trials of chronic diseases, interventions using a family-oriented approach for adults were more beneficial than solely patient-oriented interventions.40 In a review of interventions for couples and families managing chronic health problems, including common neurological diseases, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes, family interventions showed promise in helping patients and family members manage chronic illnesses.57

Among adults with diabetes, interventions including family or household members of people with diabetes may be more effective than usual care in improving diabetes-related knowledge and glycemic control.20,40,52,58–60 Family support has also been associated with improved medication adherence and blood sugar control in studies of adults with diabetes.18,44,61–62 Addressing a diabetes patient’s social–environmental support has been found to be positively associated with healthy diet and exercise.63 However, several interventions seeking to improve self-management behaviors by increasing social support from family and friends have shown varying results.64–66

Conceptual framework

We found several published conceptual frameworks that describe the theoretical underpinnings of a family-based diabetes intervention for adults.

The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care provides guidance on the major concepts underlying patient- and family-centered care across health conditions.7 In family- and patient-centered care, healthcare providers respect, listen to, and honor patient and family perspectives and choices.7 Patient and family knowledge, values, beliefs, and cultural backgrounds must be incorporated into the planning and delivery of care. Patients and families require timely, complete, and accurate information in order to effectively participate in care and decision making. Moreover, patients and families are encouraged and supported in participating in care and decision making7 Key strategies in mobilizing family support for patients with chronic health conditions may include guiding family members to set goals for supporting patient self-care behaviors, training family members in supportive communication techniques, and giving families the tools and infrastructure to assist in monitoring clinical symptoms.35,59

In terms of interventions for patients with diabetes, others have described frameworks for the inclusion of family in health interventions.12,67,68 Clinical interventions may be most effective when characteristics of patients that affect disease outcomes are integrated with perspectives of the family context.12 The family provides the arena in which patient, family member stress or support, and healthcare factors intersect, providing an ideal locus for meaningful intervention.12 Interventions must address how the family is structured, how the family solves problems, and how family members manage emotions. Interventions must also address patients’ and family members’ beliefs and expectations, family stresses, and allocation of the responsibilities of disease management. Other frameworks stress the importance of biculturalism and integrating cultural knowledge, skills, practices, and identities into diabetes self-management interventions for racial/ethnic minorities.69 Furthermore, couples-based interventions ought to address the behaviors, feelings, and thoughts of both partners.68 This approach recognizes the interdependence of partners, and that their interaction affects them both, not simply the behavior of one affecting the other.70

Objective

Considering that adults with diabetes depend on the support of family for assistance in managing their diabetes, examining family-based interventions for adults with diabetes is important in understanding how to strengthen current diabetes self-care programs. In the past decade, several studies have tested family-based interventions among adults with diabetes. We systematically reviewed published family-based interventions for adults with diabetes from the years 1994–2014, assessed the level of family participation, and considered how this involvement affected the patients’ outcomes.

Methods

We searched for family-based diabetes self-management intervention articles published from January, 1994 to October, 2014 using the electronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. We used prespecified Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords to identify evaluation studies (Evaluation, Effectiveness, Improvement, Controlled clinical trial, Randomized, Randomized controlled trials) that were designed to test diabetes self-management interventions (Intervention, Education, Self-management, Self-care, Problem solving, Program, Social support), were family-based (Family, Couple, Significant others, Spouse, Relationship, Relatives, Caregiver, Partner), and targeted adults with diabetes (Diabetes mellitus, Diabetes mellitus, Type 2). Appendix 1 describes in further detail the search terms used in the database searches. We supplemented our electronic database search with a hand search of issues from selected journals with a high likelihood of publishing diabetes self-management intervention studies (Diabetes Care and The Diabetes Educator). We also hand searched related articles and references cited in previously published systematic reviews of family-based interventions.20,31,40,52,57,60,65,71–73

To be included in our review, a study must have been conducted in the United States, be published in English or Spanish, and be focused on improving diabetes treatment processes and patients’ outcomes. We included all study types in our review (e.g., randomized controlled trials, prepost, and pilot) that met our inclusion criteria. We excluded studies that focused solely on diabetes prevention or targeted patients under the age of 19 or women with gestational diabetes. If studies included patients with other chronic conditions other than diabetes or included patients at risk for diabetes in addition to patients with diabetes, we included only those studies that reported results of subgroup analyses conducted with the subsample of diabetic patients. We excluded studies that only reported outcomes aggregated across patients and family members that made it difficult to interpret the impact of the program on index patients with diabetes.

From the PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO database searches, we identified 2340 unique articles. Three co-authors (AAB, AB, and MTQ) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the first 10% of articles (234 articles) identified through the database searches to determine whether articles met inclusion or exclusion criteria. We subsequently met to discuss discrepancies and to reach consensus. We repeated independent review of the titles and abstracts of the next 10% of articles two more times until we reached a κ greater than 0.60 that indicated moderate to substantial agreement among reviewers. The remaining titles were then divided among the three co-authors to independently review. The title and abstract review yielded a total of 200 articles in need of full text review to determine their inclusion or exclusion in the systematic review.

Once we had established an adequate κ, one co-author (AB) completed a title and abstract review of the 2010–2014 issues of Diabetes Care and 2009–2014 issues of The Diabetes Educator. Through the hand search, 76 additional articles were identified that were in need of full text review. Hand searches of reference lists of relevant articles identified through the database and journal hand searches yielded an additional 28 articles in need of full text review.

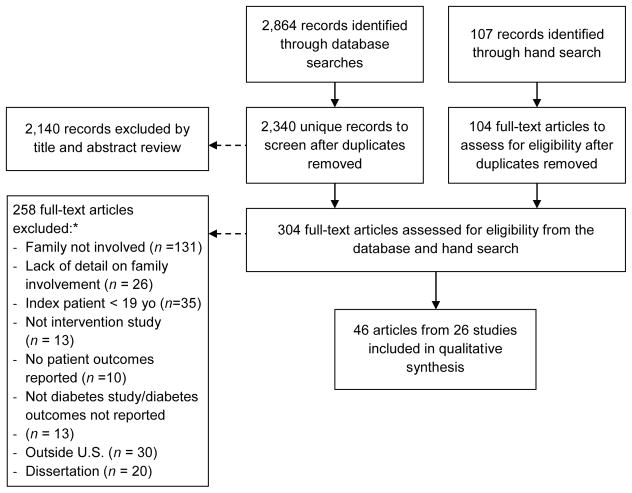

We then divided the 304 articles from the database and hand searches between three co-authors (AAB, AB, MTQ) and independently reviewed the full text of the selected articles. During the full text review, we noted that many studies mentioned family involvement in the interventions but lacked detail on how the family was involved in the study procedures. Since our focus was on the family-based nature of interventions, we included only studies that described the role and activities of family members in the intervention, provided a qualitative or quantitative assessment of outcomes related to families, or reported outcomes associated with family members’ participation. We excluded studies that did not provide details in their background, methods, results, or discussion sections regarding the role and activities of family members in the intervention or outcomes related to family involvement. Using PRISMA guidelines, our literature-search flowchart is depicted in Figure 1.74

Figure 1.

Literature search flowchart. *Several articles were excluded for more than one reason, so numbers do not add up to 258.

Data abstraction

We used a validated instrument to guide our abstraction.75 We abstracted data from each study into a table (Appendix 2) that included the objective of the study, the setting, the study design, the population sampled, a description of the intervention, and patient outcomes reported. Each study in the table was given a quality score by two members of the research team using an adapted questionnaire based on the Downs and Black guidelines (27-point scale: 0 worst, 27 best).76 The Downs and Black questionnaire is a valid and reliable checklist that assesses both randomized and non-randomized studies, provides an overall score of study quality, and includes five subscales that measure quality of reporting, external validity, bias, confounding, and power.76 We report the average of the two quality scores. We abstracted data into a separate table (Table 1) to describe how the study defined family, how family was involved, the level of family participation in the intervention, and any outcomes related to family involvement.

Table 1.

Family participation in the interventions and family outcomes.

| Reference | Definition of family | Description of family involvement | Level of family participation | Family outcomes | Quality score (out of 27) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary (2004)78 Gary (2009)79 |

Not reported | The clinical algorithms used in the intensive intervention addressed several areas, including socioeconomic issues, and took into consideration patients’ caregiver concerns. Also as part of the intensive intervention, the CHWs made home visits to study participants and reported interacting with family, for example, in teaching family members of a patient with poor eyesight to perform glucose monitoring and in reviewing foods in the kitchen cabinet and refrigerator. | Not reported | None reported | 24.5 |

| Gary (2003)77 | Not reported | The CHW was intended to serve as a liaison between the healthcare system and the family, in addition to providing diabetes education and social services. She monitored participant and family behavior, reinforced adherence to treatment recommendations, and mobilized social support. | Not reported | None reported | 23.5 |

| Anderson-Loftin (2005)93 | Family members | A traditional African American (AA) meal prepared with low-fat techniques and ingredients was served to participants and family members following most classes. Meals were framed as social events, such as a church homecoming supper or Fourth of July picnic. Participation of family members was encouraged not only to integrate black cultural traditions associated with food but also to capitalize on the value of family and to provide transportation, a common barrier in rural areas. The peer–professional discussion groups used an approach that facilitated emotional support from peers and family and is the preferred group structure of southern AAs. | Not reported | None reported | 23 |

| Rosal (2009)82 Rosal (2010)81 Rosal (2011)80 |

Significant others (SOs), defined as family members or friends living in the participant’s household | SOs were invited to attend the group sessions to elicit home-based support. Group sessions included culturally popular activities (e.g., eating together as a family and, if possible, involving the family). Group meals accompanied by discussion guides stimulated discussion around ways of implementing the recipes at home, acceptability to family and friends, and steps to trying new eating styles at home. | Not reported | None reported | 22 |

| Samuel-Hodge (2006)95 Samuel-Hodge (2009)96 |

Family members and friends | One intervention focus was on organizing education around the “church family,” which included congregants, family, and friends. This focus was viewed as one way to deliver the intervention in a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner. Family members were included as study participants and family and friends were invited as guests to group sessions. | Not reported | None reported | 21.5 |

| Vincent (2007)97 Vincent (2009)98 |

Support person; family member | Participants were encouraged to bring a support person to the 8 weekly 2-h group sessions since support from friends and family has been shown to improve glycemic control. Inclusion of cultural content included addressing family issues. Additionally, participants were given low literacy, Spanish-language materials to share with their family members. The cultural concept of familismo (family support and cohesiveness) and the importance of family support to facilitate lifestyle changes needed for DSM was the basis for including family in the intervention. | Not reported | In postintervention focus groups, participants reported they and their families benefited from the intervention. “Benefit to families” was one of only two major themes identified in the focus group data. Family benefited from healthier eating and became more supportive of participants’ lifestyle changes. | 21 |

| Toobert (2010)84 Toobert (2011a)83 Toobert (2011b)85 Osuna (2011)120 Barrera (2014)86 |

Family members | The social support group component taught participants how to problem solve and how to mobilize social support among family and friends. The intervention also included a “Family Night” where family members could join participants during the social support group portion of the meeting, hear an overview of ¡Viva Bien! activities, celebrate the diabetes participants’ achievements, and exchange questions and answers. Family nights were viewed as vehicles for increasing the families’ support for participants’ intervention engagement. Families were also invited to a final celebratory meeting. The involvement of family was viewed as being consistent with the Latino cultural value of familismo. | Not reported | Family support had an effect on increases in physical activity (PA) even after accounting for the effects of group support. Study authors suggested the finding might be attributed to the involvement of family in the intervention and dedicating sessions to the mobilization of family and friend support. | 21 |

| Aikens (2014a)109 Aikens (2014b)110 |

Family member or close friend living outside the patient’s home (informal caregiver); to be ≥ eligible, informal caregivers needed to be ≥18 years old, have no history of cognitive or severe psychiatric impairment, and have access to email. | Patients received weekly interactive voice response (IVR) calls to assess health status and self-care and to provide tailored, prerecorded support messages. Patientss could opt to designate one family member or close friend to receive emailed summaries of each completed call along with structured suggestions on supporting the patient’s DSM. Participating caregivers underwent DVD-based training on communicating effectively with the patient and any in-home caregiver that may be involved. Intervention strategies were based upon the assumption that patients, informal caregivers, and healthcare teams can use frequent information updates about the patient’s health and self-care to promptly identify emerging problems and improve illness self-management. One of the overall goals of the intervention was to generate guidance on DSM support for patients’ informal caregivers via structured emails. | 39% of patients participated with an informal caregiver; based on patients’ feedback at baseline, the lack of caregiver involvement was usually due to personal preference and not unavailability of a person to play this role. Caregiver participation was significantly more likely among patients with lower income and lower health literacy levels. |

Rates of engagement were higher among pts enrolling with an informal caregiver (87.7% of assessments completed versus 81.6% for those not participating with an informal caregiver, P = 0.008). Patients who participated with an informal caregiver were less likely to report frequent high glucose levels (P = 0.021) and more likely to regularly check their BP (P = 0.017) than those patients not participating with an informal caregiver. | 21 |

| Kim (2009)99 Song (2010)100 |

Family members | During the educational program, study participants, their family members, CHWs, and diabetes educators actively engaged in group education in a synergistic manner. The program recognized the traditional Korean cultural values of close familial interdependence and social relationships. The researchers encouraged the active involvement of other family members in the group education to create a synergistic group interaction while building an environment promoting family and social support. This strategy intended to enhance the deep cultural tailoring of the intervention by supporting the social/environmental forces influencing health behavior. | Not reported | None reported | 20.5 |

| Brown (2002)91 Brown (2005)92 Brown (2013)90 |

A family member, preferably a spouse or first-degree relative who would participate as a support person. If a family member was not available, a close friend participated. | Subjects were required to identify a family member or close friend to participate with them in the intervention as a support person. Family/friends were invited to attend 12 weekly education meetings and 14 biweekly support group meetings to talk about DSM problems and the impact of diabetes on the family. Social support was fostered through family members and friends, as well as other group participants and intervention leaders. Group leaders emphasized support from family members and encouraged support persons to improve their health habits. | Not reported | None reported | 20 |

| Two Feathers (2005)103 Two Feathers (2007)107 Kieffer (2004)119 |

Family members; family member or friend | Kieffer (2004) reports preliminary focus group findings that identified the importance of family support for DSM and led to the inclusion of family members in the intervention and family and social support being a key characteristic of the intervention. Participants were encouraged to bring a family member or friend to group diabetes self-management education (DSME) meetings. The Family Health Advocates worked with patients with diabetes and their family members, providing them group DSME classes, case management and referral services. Role-playing was used to improve communication with family members about DSM. | Not reported | Postintervention, patients with diabetes reported they were encouraging their family members to eat healthier meals and to exercise with them. | 20 |

| Utz (2008)88 Jones (2008)89 | Supportive family and/or friends | Supportive family and/or friends were invited to selected group sessions to obtain information about diabetes and family/peer support. During one of the sessions, family members and friends were given a “Helpful Hints for Family Members” guideline developed by two of the study’s authors about how to be supportive to the person with diabetes. Along with the guideline, the family member or friend had an opportunity to view three videos about family communication around diabetes. The facilitator also guided a discussion during which time family could ask questions and share their experiences and the participants could discuss how interactions between those with diabetes and their family members/ friends affected DSM. Family and friends were also invited to participate in a cooking demonstration by a dietitian to show how to cook healthy meals that are easy and taste good. | 6 family and friends (1 mother, 1 adult son, 2 friends, 1 adult daughter, and 1 wife) came to the invited sessions. | Several of the participating support persons expressed that they appreciated the opportunity to attend one session with their loved one to understand diabetes better. | 20 |

| Castejón (2014)101 | Either a family member or a friend Attending partners were a spouse, friend, sibling, or child |

The support person was asked to come with the study participant for every clinical screening and educational session, when available. Both the participant and support person received a physical assessment at the clinical screenings, including a recording of weight, height, waist circumference, BMI, and BP. Participants were given two copies of their clinical results, one for their primary care provider and one for their own records, and were debriefed about their clinical values. During the group educational session, the pharmacist led a closing discussion that focused on misconceptions brought up by participants and their partners during the earlier focused discussion group that was moderated by a project coordinator (Master in Public Health level). Family was involved in the study because the patient’s family was viewed as one of three major social and environmental factors affecting a patient’s DSM and should thus be a target for DSM interventions to encourage appropriate nutrition, exercise, self-management, medical treatment, involvement, and support. | 67% of control and 79% of the intervention group patients had a partner attend at baseline; 42% of controls and 33% of the intervention group had partners at both clinical screening visits. Most partners were female and had an average age of 48 (20–77) years. |

None reported | 19.5 |

| Gilliland (2002)114 Gilliland (1998)117 Carter (1997)118 |

In the family and friend (FF) arm, patientss with diabetes received the intervention in family and friend groups | Gilliland (1998) and Carter (1997) report on preliminary research that led to the inclusion of family and addressing family support in the intervention. The FF arm included activities to encourage social interaction and discussion about diabetes among members of the group. The mentor encouraged them to discuss and share their stories about living with diabetes. The FF arm joined in physical activities as a group and shared a healthy meal. | Not reported | None reported | 19 |

| Corkery (1997)94 | Family member | Family members could attend education sessions. In the CHW arm, the CHW acted as a liaison between the patients, their families, and health care providers. For the non-CHW intervention group, encounters took place only between the nurse and the patient and family member. |

Patients were defined as having family participation if a family member attended most of the education sessions. The family participation rate was 31%. | None reported | 18.5 |

| Hu (2014)21 | Adult family member who resides in the diabetes patient’s household, is ≥ 18 years of age, and is willing to participate | There were two family sessions, for which the family unit, including multiple members, was invited. The first family session explained the purpose of the study, the format of the intervention, and requirements of participants. Informed consent was obtained from the participant and participating adult family member, and baseline data were collected. The last family session included postintervention data collection and discussions with family members about DSM. Each participant was also asked to bring at least one family member to the 8 weekly group intervention meetings that took place between the two family sessions. A group discussion with open-ended questions on family support was facilitated at the end of the first and last group meetings. The last group session also included a celebration of completion of the program for both participants and family members with a certificate and food. Focusing on family involvement and family centeredness was viewed as an important aspect of the intervention due to the Hispanic cultural value of familismo. Support from family members was viewed as an important social factor affecting behavior change; thus, the intervention focused on fostering behavioral changes through building family support. | 37 family members enrolled in the study. At baseline, family members were primarily female (70%) with an average age of 40.6 years and an average BMI of 32.7 kg/m2; 51% had hypertension, 87% had a high school education or less, 89% had a household income <$10,000, and 78% were from Mexico. |

Significant changes in family member BMI (−0.25 kg/m2) and diabetes knowledge from baseline to postintervention No significant changes in waist circumference, BP, PA, and fruit and vegetable consumption, but trend noted in SBP, PA and fruit and vegetable consumption (0.05 < P < 0.09) | 17.5 |

| Williams (2014)113 | Supportive family member or friend to serve as a support person | One intervention strategy was involving a key family/friend as a supporter for achieving patient DSM goals. Some of the group DSME sessions also involved the participation of a supportive family member or friend to encourage shared learning and to enhance the ability of the support person to know how to be helpful. | Not reported | None reported | 16 |

| Anderson-Loftin (2002)102 | Family members | Families were encouraged to participate in the dietary education group sessions and discussion groups to capitalize on the value of family and to provide transportation. Healthy meals were served to participants and family members at the end of the first class. The second class was a cooking class, and after the meal preparation, participants and family dined and were encouraged to share their own healthy recipes. The home visit by the nurse case manager (NCM) was also meant to solicit family support. | The article reports many family members actively participated in the cooking class. | None reported | 15.5 |

| Kluding (2010)105 | Family members or other supportive people | Family members or other supportive people were invited for all educational sessions and were specifically included for two sessions: “family support day” in week 5 and “graduation ceremony” in week 10. | Not reported | None reported | 15 |

| Trief (2011)68 | Couples were enrolled; patients with diabetes and their partners both had to be >21 years of age and been married or partnered >1 year | In the couples’ intervention arm, patients and partners participated in exercises to promote collaborative problem-solving as they worked on their goals. The intervention included two phone calls on speakerphone that focused on couples’ communication, particularly around emotions and situations that might be problematic for the patient, so that the partner could share his/her feelings and they could discuss ways to problem solve together. Homework and discussion tasks involved both partners in goal setting, contracting, and skills to improve communication. | Not reported | None reported | 14.5 |

| Islam (2013)111 Islam (2012)121 |

Family members | Islam (2012) reports on focus group findings that led to the inclusion of family and addressing family support in the intervention. Based on the findings from the preliminary focus group study, it was determined that strategies to overcome family conflict and promote positive family communication and family activities to promote social support would be incorporated into the intervention. Thus, “Effects of family support on managing stress” was one of the session topics. CHWs also encouraged family support during the one-on-one visits. | Not reported | CHWs qualitatively reported having an impact on family members and on facilitating family support between participants and their family members. | 14.5 |

| Brown (1995)50 | A family member, preferably a spouse or first-degree relative who would participate as a support person. If a family member was not available, a close friend participated. | Each participant was required to identify a support person who would participate in the educational and support sessions. The bilingual Mexican-American lay community worker conducted follow-up support sessions with patients/families after the education sessions were done. One of the emphases during sessions was support from family, friends, and other subjects. Family/friends were invited to the support session to talk about diabetes self-management (DSM) problems and the impact of diabetes on the family. Encouraging support from family members and motivating them to improve their health habits was also emphasized. | On average, family members/support persons attended 6 of the 9 meetings. The size of the group, 6 patients and 6 family members, was deemed appropriate by participants. |

Family members indicated in postsession interviews that the sessions helped them to improve their health practices, particularly with regard to nutrition. Patients reported in postsession interviews that having family members/support persons at the sessions was very helpful. |

14 |

| Mendenhall (2010)106 Mendenhall (2012)107 |

Family members, including patients’ spouses, parents, and/or children | Family members attended all meetings of the Family Education Diabetes Series program. They were involved in data collection by checking and recording each other’s blood sugar, weight, and body mass index (BMI) and by conducting foot checks. Family members were viewed as program participants but not enrolled as study participants for the purposes of the research study. The program also had a session topic specifically focusing on family relationships and social support. | Not reported, except in saying that generally 35–40 community members, including patients and family members, attended meetings | None reported | 13.5 |

| Roblin (2011)108 | A supporter, defined as a family member, relative, or close friend whose support and opinion were valued by the diabetes pt, who did not live in the patient’s same household, and who agreed to enroll in the study as a support person | A family member, relative, or close friend was asked by the patient to serve in the support role. During the enrollment session, supporters were instructed in motivational coaching so they could provide effective feedback to the diabetes patient and help assess barriers to effective self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). During the intervention, a summary of SMBG adherence and results were sent to the patient or support person to prompt conversations and facilitate supportive relationships in order to reinforce the importance of SMBG and achieving good glucose control. Both the patient and supporter were asked for input about the intervention at the disenrollment session. |

Patient and supporter attended both the enrollment and disenrollment sessions | Qualitative findings indicated that support persons reported an improved ability and confidence to provide emotional and instrumental support to their paired diabetes patient in their SMBG and an improved social proximity to their paired diabetes patient. | 12 |

| Archuleta (2012)112 | Family members | Family members were invited to attend four 3-h cooking/nutrition classes with their family member with diabetes. Conducting the education together with caregivers or spouses and in a community setting with food that is socially acceptable was intentionally incorporated into the intervention as a strategy to build social support. | Class participants included family members without diabetes, but only data from diabetes patients was reported. | None reported | 12 |

| Glueck (2014)115 | Loved ones; a spouse or family member | The goal of the diabetes management and treatment support groups was to provide education and support to individuals diagnosed with diabetes and their loved ones and to promote DSM. Another critical goal for these groups was that individuals diagnosed with diabetes and their family members be active participants rather than simply attend the program passively and to make the group about the process and an experience for enhanced learning for families. Incorporation of family members active in the caregiving process in the groups was viewed as important because diabetes affects the family, and treatments and recommendations must be changed within the context of the patient’s social, cultural, and ecological environment. As such, when patients registered, they were encouraged to bring a spouse or family member to weekly meetings to also share and receive support from the group. | In 2007, 6 of 24 (25%) patients enrolled brought a spouse. In 2008, 3 of 19 (16%) enrolled brought a spouse. In 2009, attendance data was not available for the 14 patients who registered for the series. | None reported | 10 |

Note: AA, African American; BMI, body mass index; CHW, community health worker; DSM, diabetes self-management; DSME, diabetes self-management education; FF, family and friend; IVR, interactive voice response; NCM, nurse case manager; PA, physical activity; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; SO, significant other

Results

We identified 26 unique studies described in 46 articles that used family-based interventions to address diabetes self-management and outcomes among adults with diabetes. These studies are described in detail in Appendix 2.

Study design

Of the 26 studies, 13 used a randomized controlled study design (RCTs)77–101 and 11 used a prepost design.21,50,102–113 One study assigned individuals to one of three arms based on their community of residence.114 Another study reported only postintervention measures.115 Participation and follow-up rates were high for many studies, as noted in Appendix 2. Follow-up ranged from immediate postintervention to 12 months,21,80–82,90,92,95,96,99,100,111,113,114,116 24 months,77,83 and 36 months.78,79

Populations and settings

Of the 26 studies, 22 recruited patients from racial/ethnic minority populations. Studies included American Indian,106,107,114,117,118 African-American,77–79, 88,89,93,95,96,102–104,119 Latino,21,50,80–86,90,91,92,94,97,98,101,103.104,112,119,120 and Asian, including Bangladeshi American111,121 and Korean American,99,100 patient populations. Two studies did not collect or report race/ethnicity data.87,115

Studies also represented different regions across the United States, including the Midwest,104–107,109,110,119 South,21,88,89,93,95,96,101,102,108,113,115 West/Southwest,83–86,97,98,112,114,117,118,120 East,77–81,87,94,99,100,111,121 and along the Texas–Mexico border.50,90–92 Several were conducted in rural settings settings21,50,88–93,102,113 or urban settings.77–86,94,99,100,103,104,106–108,111,115,119–121 Two studies were conducted in Native American communities.106,107,114

Interventions took place in diverse settings, including community health centers,21,97,98,111 other community sites,47,50,80–82,88,89,91,92,99,100,101,103,104,106,107,111–113 academic medical centers,77,94,105,115 churches,95,96 and Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals.109,110

Intervention details

Of the 26 studies, 21 interventions were diabetes self-management interventions that offered group-based or one-to-one individualized counseling. One intervention was a cooking class.112 Four interventions incorporated home visits.77–82,102 Three studies used technology, including mobile communication technology, to support serum blood glucose monitoring,108 teletransmission for home glucose monitoring,99,100 and interactive voice response (IVR) to provide patient monitoring and self-care support between primary care visits.109,110

Interventions were led by CHWs or promotoras,77–79,90–92,94,97,98,103,104,111,119 nurses,50,77–79,90–94, 99,100,102,106,107,112 pharmacists,101,115 certified diabetes educators (CDEs),87–89,93,94,97,98,102,112,113 peer or lay leaders,50,80,82,95,96,114,117 registered dietitians (RDs) or nutritionists,50,80,82,83,85,86,90–93,95,96,99,100,102,106,107,112,115,120 physicians,106,107,115 mental health providers,87,106,107,115 nurse practitioners,21,113 health educators,80,82 tribal elders/leaders,106,107 and dentists.115

Outcome measures

Patient clinical outcomes

Clinical outcomes for index patients with diabetes varied across studies. Of the 19 studies that reported A1c, 11 found significant improvements.50,80,83,85,91,94,96,99,102,103,106,114 Seven studies noted improvement in A1c from baseline to postintervention,50,91,94,96,99,103,106 while others reported improvements from baseline to 5 months postintervention,102 30 weeks postbaseline,99 7.7 months postbaseline,94 and 12 months postbaseline.91 Four studies demonstrated short-term improvements in A1c that were not maintained at 6 months,106 12 months,80,96 or 24 months.85

Of the 11 studies that reported blood pressure outcomes, three demonstrated short-term improvements in blood pressure,21,96,106 two reported improvements at 12 months,113,114 and one reported improvements in diastolic blood pressure at 24 months.77 Among the nine studies tracking weight, four noted significant weight loss over time.93,98,101,106 Of nine studies reporting body-mass index (BMI), three found improvements in BMI in the short-term;83,85,101,113 however, for one study these results were not sustained at 12 months.113 Three of 11 studies assessing cholesterol showed improvements in lipid profiles.77,87,99

Patient psychosocial outcomes

Several studies assessed psychosocial outcomes for patients. All three studies measuring depression found improvements in patients’ reported depressive symptoms.99,109–111 One study measured diabetes distress and found improvements.109,110 Of the four studies that assessed quality of life, three demonstrated improvements.21,96,99 Of 10 studies measuring self-efficacy, seven found improvements.21,80,83,85,99,105,108,111 The ¡Viva Bien! program also noted improvements in patients’ perceived supportive resources.83,85 One study reported that patients felt increased emotional and instrumental support in blood glucose self-monitoring.108

Patient diabetes self-management behaviors

Of the 13 studies measuring diabetes knowledge, 12 noted improvements in patients’ diabetes knowledge.21,50,80,91,94,96,99,103,107,111,113,115 Of 15 studies assessing diet, 11 demonstrated improvements in dietary habits.21,80,83,85,93,94,102,103,107,111,112,115 A study utilizing cooking classes showed significant improvements in dietary behaviors, including caloric intake, saturated fat, cholesterol, and fat consumed.112 Out of 12 studies assessing exercise, five found improvements in patient physical activity.83,85,107,111,113,115 However, one study found that improvements in physical activity were not sustained at 12-month follow-up.113 Six out of eight studies measuring patients’ blood glucose monitoring noted improvements,21,80,97,108–110,115 and two out of six measuring medication adherence noted improvements.109,115 Some studies found improvements in some self-care behaviors but not in others.21,98,97,103,111,113

Healthcare utilization

One study found a significant decrease in emergency room visits by intervention participants but not in the number of hospitalizations.79 Another study found improvements in the number of acute care visits but no change in hospital length of stay.102

Cost

Only two studies reported the cost of the intervention.91–93

Patient outcomes by family involvement

Of the 26 studies, 17 studies did not report patient outcomes by family involvement.77,79,80,88,89,93,96–103,105–107,111–113,115 Four studies required patients in all arms to enroll with a family member/support person, thus precluding them from assessing outcomes by family involvement.21,50,90,91,108

Three studies reported positive effects of family involvement. Barrera reported that family support had an effect on increases in physical activity after accounting for the effects of group support.86 Gilliland demonstrated a decrease in diastolic blood pressure in the family arm.114 Aikens conducted subgroup analyses comparing patients with family involvement to those without and found that patients enrolling with an informal caregiver had higher rates of engagement, were less likely to report frequent high glucose levels (P = 0.021), and more likely to regularly check their blood pressure (P = 0.017).110

However, two studies found no impact of family involvement. One reported results from subgroup analyses comparing patients with family involvement to those without and found that family participation in education sessions was not a significant factor in program completion.94 In their telephone-based intervention, Trief et al. compared outcomes of patients with family involvement to those without and, contrary to their hypothesis, found that results in the individual intervention group appeared to be better overall than those in the couples intervention group.87

Family participation and outcomes

Table 1 describes family participation in the interventions and family outcomes. Of 26 studies, most defined family members as spouses, parents, children, or relatives.50,80,82,90–92,106,108,115 One study involved couples.87 Two studies required that the family member must reside in the patient’s household.21,80,82 Many studies stated that family members were included in the intervention without explaining who they defined as being a family member. Some studies included other supportive people105 or friends in lieu of a family member for index participants who chose this option.50,88,89,90,91,101,103,104,113,114 One further specified that the friend had to be living in the participant’s household,80–82 while another stated the family member or close friend must be someone living outside the patient’s home.109,110

Family involvement varied across studies. Most studies noted that families were invited to attend the intervention classes or meetings.21,50,80,82,83,85,89,91,93–95,97,98,100–102,106,107,112,113 In some studies, authors stated that family members were enrolled in the study.21,87,95,108 Some interventions included family-themed topics in the education sessions, such as support of family in managing stress and traditional cultural values regarding familial and social relationships.21,80,82,88,89,93,97,98,100,103,104,111,119,121 In other studies, family participated in physical activities or shared a healthy meal.83,85,88,89,93,114,120 Family support was encouraged by CHWs.77–79,100,111,121 Excluding the interventions that specifically enrolled dyads,21,50,87,90,91,108 only some studies noted actual rates of family participation,50,89,94,101,109,110,115 which ranged from 16% to 79%.

In Aikens et al., patients received weekly IVR calls to assess health status and self-care and to receive tailored, prerecorded support messages. Family caregivers were notified of the results of each call and were given suggestions for self-management support.109,110

In Roblin’s study,108 family supporters were instructed in motivational coaching so they could provide effective feedback to the patient and help assess barriers to effective self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). During the intervention, a summary of SMBG adherence and results were sent to the patient and their support person to prompt conversations and facilitate supportive relationships in order to reinforce the importance of SMBG and achieving good glucose control. Both the patient and supporter were asked for feedback about the intervention at the final session.

In Trief’s study, patients and partners participated in exercises to promote collaborative problem solving.87 Two phone calls on speakerphone were conducted with each couple, focused specifically on the couples’ communication. Homework and discussion tasks involved both partners in goal setting and improving communication skills.87

While most studies focused on encouraging family members’ supportive behaviors, five studies reported addressing emotions and situations that might be problematic for the patient.50,87,91,101,109

Few studies reported on actual outcomes for participating family members. Some studies reported qualitative findings that the intervention improved family members’ ability to support to their loved one with diabetes regarding SMBG and also helped family members to improve their own diets.50,98,108 One study noted significant improvements in BMI and diabetes knowledge among family members but no changes in waist circumference, blood pressure, physical activity, or fruit and vegetable consumption.21

Quality scoring

The quality scores for the studies ranged from 10 to 24.5 with a mean score of 18. Of the 27 criteria composing the quality score, the studies we reviewed scored the lowest in the following categories: attempt to blind the study subjects, attempt to blind those measuring the main outcomes, reporting of adverse events, using a representative sample, and reporting of sample-size calculation. Appendix 3 describes the quality scores in further detail for each study.

Fifteen studies had above average quality scores (≥ 18). Of these 15 studies, seven had substantial family involvement.88–92,97,98,101,103,104,109,110,114,117–119 Of these seven studies, only two studies found improvements in A1c.90–92,103,104,119 Four of the seven studies showed no improvement,88,89,97,98,101,114 and one study did not measure A1c.109,110 There were two more studies that reported substantial family involvement in the study intervention; however, they both had lower quality scores and either did not measure108 or did not find a significant improvement in A1c.87

Discussion

Since the majority of disease-management activities for many adults occurs within the family environment, involving families in diabetes self-care interventions may be a key mechanism to improving diabetes outcomes for patients. We systematically reviewed the literature from 1994 to 2014 and identified 26 studies that reported findings from family-based diabetes self-management interventions for adults with diabetes. Studies were conducted in a range of patient populations and settings but reported varying levels of family involvement and impact on patient outcomes.

Many studies used scientifically rigorous study designs, such as randomized controlled trials; however, the quality of the studies varied significantly.76 Some reports included an in-depth description of methods or referred to previously published study protocols; however, many other studies did not report details on their methods, including power calculations. Quality scores were also lower for studies that did not report attendance or follow-up rates or assess fidelity to the intervention. Furthermore, we had to exclude several studies from our review because they did not describe in detail the involvement of family in the background or methods section. Previous systematic reviews of family-based interventions have found a similar lack of detailed descriptions in the methods used.73 The family-based intervention was often offered as a group program that was compared to either usual care or individual educational sessions. Studies may need to compare similar interventions both with and without a family component to truly assess the impact of including family on patient outcomes. More studies are needed that utilize rigorous study designs, adhere to reporting guidelines,122 assess outcomes specific to diabetes patients, and include relevant comparison groups to fully understand the impact of family-based interventions on patient outcomes.

We found that the involvement of the family members and integration of families into the interventions varied widely across studies. Some studies used a strong theoretical framework for the inclusion of family and described family-based activities and involvement in great detail.21,87,101,108–110,115 Many included family-themed topics in the education sessions, such as teaching ways to manage stress and having family members engage in physical activities and healthy meals together with patients. Other studies encouraged family support through home visits and interactions with CHWs. However, many studies did not describe a theoretical basis for the involvement of family or report on the extent of family involvement. Several studies in our review mentioned that families were invited to intervention meetings, classes, and home visits but lacked detail on the content that was designed for family members, how family members interacted in the class, and what family outcomes the interventions were targeting. Few studies reported on family attendance or participation rates in the intervention. Also, many studies did not define who qualified as a “family member,” a detail which should be specified since the definition can be very broad and may include friends and other support persons,67 and the level of support these contacts provide may differ.123 Who is considered a “family member” may also vary with cultural context in different populations. Without a clear understanding of the theoretical basis of involving family, who could serve as a “family member,” and how family is involved in the intervention and to what extent, it is challenging to draw conclusions of the impact of including family in self-care interventions.

Many interventions in our review measured patients’ clinical outcomes, but their impact varied. Several studies found improvements in A1c in the short term; however, studies with follow-up beyond 1 year found that these improvements were not maintained. Some studies demonstrated improvements in other clinical patient outcomes important to patients with diabetes, such as blood pressure, weight loss, and cholesterol; however, many studies found no significant changes. The impact of self-care interventions on long-term patient outcomes can be challenging after the intensive intervention period ends,124 but involving family in these interventions should help support patients in sustaining changes in self-care and in maintaining improvements.12 In addition to strengthening the family-based components of self-care interventions, having more intensive or longer interventions and providing linkages with the healthcare system and the community may be needed to affect patient clinical outcomes.124,125

Studies that assessed psychosocial outcomes found improvements in patients’ depressive symptoms, diabetes distress, quality of life, self-efficacy, and perceived social support. Many studies also found improvements in patients’ diabetes knowledge, self-care behaviors, and dietary habits, but several studies found no change in these outcomes or improvements in only some self-care behaviors. This finding is not surprising, since social support may be associated with some self-care behaviors more than others.33,66 Based on our review, it seems that family-based interventions may impact psychosocial outcomes, diabetes knowledge, and some self-care behaviors in the short-term. Further research is needed to assess the maintenance over time of improvements in patients’ psychosocial and behavioral outcomes and how these changes can be utilized to improve physical health. Involving families in diabetes education interventions may enable them to be more supportive of the patient and improve the patient’s feeling of being supported in their diabetes self-care.126

Through their participation in health interventions, family members may also experience improvements in their own knowledge about diabetes, skills in supporting loved ones with diabetes, and changes in their own health behaviors and health outcomes. While the studies in our review measured a large range of patient outcomes, few reported on family member outcomes. Some studies found that family members were highly satisfied with the interventions and that their involvement improved their ability and confidence to provide emotional and instrumental support to their loved ones with diabetes.50,108 A few studies noted improvements in family members’ BMI, diabetes knowledge, and diet and exercise behaviors.21,50,97,98,103,104 However, we found many studies that we excluded from our review because family members’ results were aggregated with the patients’ outcomes. Ultimately, failure to separately assess effects on both the patient and family member provides an incomplete picture regarding the effectiveness of these health education interventions.40 Lack of improvement for the patient might be explained by negative effects of the intervention on the family member.31 Future studies need to evaluate the benefits of diabetes self-management interventions for both the patient and the family member.40

We found several studies conducted with diverse patient populations that were culturally tailored to the target audience. The inclusion of family in diabetes self-care interventions is important for many patients from racial/ethnic minority populations and is an important aspect of culturally tailoring educational programs.46–48,67,124,127–130 The literature notes many benefits of involving families of patients from racial/ethnic minority groups in diabetes interventions, including the chance to provide family members with knowledge about the disease, dispelling myths and misconceptions about the disease, and teaching them ways to support patients in self-care.8, 33,37,46–48,131 Families are also eager to learn strategies for being supportive of their family members with diabetes.33,127 While the studies we reviewed included diverse patient populations and settings, only two studies targeted Asian Americans.99,100,111 Further studies using family-based diabetes interventions need to target Asian subpopulations, many of which have high rates of diabetes.1

Considering more than a quarter of adults aged 65 and older have diabetes,1,132 there is a pressing need for family members to support older patients with diabetes. In our review, only a few studies targeted older adults.105,109,110,113,114 Only one study was conducted in the VA, a setting that provides healthcare for many older patients with chronic diseases.109,110,133 Considering many older patients have greater needs for social support and may need assistance in diabetes self-care, future studies should be conducted among older adult and veteran populations.132–134 One study found that elderly diabetic patients whose spouses participated with them in a diabetes education program showed greater improvements in knowledge, metabolic control, and stress level than those who participated alone.135 Considering the burden of diabetes among older adult populations, involving family members and caregivers in interventions for older patient populations may be crucial for providing older patients with instrumental and social support related to their diabetes management.

Future family-based interventions may also need to consider the role of gender in family-based interventions and include an assessment of cost and healthcare utilization. Previous studies have noted differences in support received by female patients with diabetes.65,126,136 We found some studies that assessed the impact of the intervention by gender.90,93 Future studies should explore how family support may differ by gender of the patient and of the support person, and how this may affect clinical outcomes. Family-based studies should also include measures beyond clinical, behavioral, and psychosocial outcomes, such as cost and healthcare utilization. We found few studies which measured cost of the intervention or patients’ healthcare utilization.79,91–93,102 Assessing the cost-effectiveness of family-based interventions will help to further quantify the benefit of including family in interventions for diabetes. Furthermore, assessing healthcare utilization, such as hospitalizations and emergency room visits, is also important because it bears a heavy expense on patients and may indicate worsening of disease or lack of instrumental or social support.

Limitations

Although we found many studies reporting on family-based interventions to improve adult diabetes outcomes conducted over the past 20 years, there were many limitations to this literature. Given the heterogeneous designs and varying patient populations and settings, we could not compare effect sizes across studies. Only a few studies reported cost data, thus making cost effectiveness difficult to assess. Although we made an effort to search multiple databases and conduct hand searches, there may be family-based interventions that we did not identify or that we excluded because they did not describe family involvement or did not report outcomes specific to the patients with diabetes. In addition, some organizations that have conducted interventions to improve diabetes care may not have published their findings in peer-reviewed journals. Our review was also limited by publication bias, because positive findings tend to be published more frequently than null findings.

Conclusions

Developing diabetes interventions that include family may be critical in improving the health of adults with diabetes. We found only two studies that were of high quality and with substantial family involvement that reported improvement in A1c.91,103,104,119 Owing to the heterogeneity of the study designs, interventions, extent of family involvement, and reporting of results, it is difficult to determine whether and how family involvement in diabetes interventions can affect patient and family members’ health outcomes. Future studies should clearly describe the role of family in the intervention, provide details on family-based topics in the intervention, assess the quality and extent of family participation, and compare patient outcomes with and without family involvement. While including families in diabetes self-management interventions for adults has a strong theoretical and cultural basis for many patient populations,6,12,124 there is much work to be done to fully understand what roles family members should play in family-based diabetes self-management interventions and how their involvement can affect patients’ diabetes outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Haley Johnson for her assistance in conducting and organizing our database search and Patricia Fernandez for her help in formatting. We are also indebted to our medical librarians, Deborah Werner and Ricardo Andrade, for their assistance in our database search and to Yue Gao for her help calculating our kappas. This research was supported by grants from the University of Chicago Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR024999), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK20595) and the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949). Dr. Baig is supported by a NIDDK Mentored Patient-Oriented Career Development Award (K23 DK087903-01A1).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 (Suppl 1):S14–80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deakin T, McShane CE, Cade JE, Williams RD. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2005:Cd003417. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003417.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:488–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner R, Holman R, Cull C, et al. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Innovative care for chronic conditions : building blocks for action : global report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Noncommunicable Disease and Mental Health Cluster. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. [Accessed Dec 31, 2014];What is meant by the word “family”? http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

- 8.Weiler DM, Crist JD. Diabetes self-management in a Latino social environment. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:285–92. doi: 10.1177/0145721708329545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesla CA, Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Gilliss CL, Kanter R. Family predictors of disease management over one year in Latino and European American patients with type 2 diabetes. Fam Process. 2003;42:375–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denham SA, Ware LJ, Raffle H, Leach K. Family Inclusion in Diabetes Education A Nationwide Survey of Diabetes Educators. The Diabetes Educator. 2011;37:528–35. doi: 10.1177/0145721711411312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacs Burns K, Nicolucci A, Holt RI, et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2): Cross-national benchmarking indicators for family members living with people with diabetes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2013;30:778–88. doi: 10.1111/dme.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Bartz RJ, et al. The family and type 2 diabetes: a framework for intervention. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24:599–607. doi: 10.1177/014572179802400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burg MM, Seeman TE. Families and health: The negative side of social ties. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;46:1097–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicklett EJ, Heisler ME, Spencer MS, Rosland AM. Direct social support and long-term health among middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68:933–43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton WW, Mengel M, Mengel L, Larson D, Campbell R, Montague RB. Psychosocial and psychopathologic influences on management and control of insulin-dependent diabetes. International journal of psychiatry in medicine. 1992;22:105–17. doi: 10.2190/DF4H-9HQW-NJEC-Q54E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith LS, Field BJ, Lustman PJ. Life stress and social support in diabetes: association with glycemic control. International journal of psychiatry in medicine. 1990;20:365–72. doi: 10.2190/APH4-YMBG-NVRL-VLWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardenas L, Vallbona C, Baker S, Yusim S. Adult onset diabetes mellitus: glycemic control and family function. Am J Med Sci. 1987;293:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, Egede LE. Quantifying direct effects of social determinants of health on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:80–7. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armour TA, Norris SL, Jack L, Jr, Zhang X, Fisher L. The effectiveness of family interventions in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2005;22:1295–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu J, Wallace DC, McCoy TP, Amirehsani KA. A family-based diabetes intervention for Hispanic adults and their family members. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:48–59. doi: 10.1177/0145721713512682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denham SA, Manoogian MM, Schuster L. Managing family support and dietary routines: Type 2 diabetes in rural Appalachian families. Families, Systems, & Health. 2007;25:36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manoogian MM, Harter LM, Denham SA. The storied nature of health legacies in the familial experience of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Family Communication. 2010;10:40–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trief PM, Morin PC, Izquierdo R, et al. Marital quality and diabetes outcomes: The IDEATel Project. Families, Systems, & Health. 2006;24:318. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Family support, medication adherence, and glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1239–45. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayberry LS, Rothman RL, Osborn CY. Family members’ obstructive behaviors appear to be more harmful among adults with type 2 diabetes and limited health literacy. Journal of health communication. 2014;19 (Suppl 2):132–43. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.938840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter-Edwards L, Skelly AH, Cagle CS, Appel SJ. “They Care But Don’t Understand”: Family Support of African American Women With Type 2 Diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2004;30:493–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi HJ, Silveira MJ, Piette JD. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2010;6:22–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens MA, Franks MM, Rook KS, Iida M, Hemphill RC, Salem JK. Spouses’ attempts to regulate day-to-day dietary adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2013;32:1029–37. doi: 10.1037/a0030018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayberry LS, Egede LE, Wagner JA, Osborn CY. Stress, depression and medication nonadherence in diabetes: test of the exacerbating and buffering effects of family support. J Behav Med. 2015;38:363–71. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9611-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi EM. Review and Meta-analysis of Couple-Oriented Interventions for Chronic Illness. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40:325–42. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Kanter RA. Depression and anxiety among partners of European-American and Latino patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1564–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]