Abstract

Background & Aims

Most studies of trends in diverticular disease have focused on diverticulitis or on a composite outcome of diverticulitis and bleeding. We aimed to quantify and compare the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticular bleeding and diverticulitis overall and by sex and race.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2000 through 2010. We identified adult patients with a discharge diagnosis of diverticular bleeding or diverticulitis. Using yearly US Intercensal data, we calculated age-, sex-, and race- specific rates, as well as age-adjusted prevalence rates.

Results

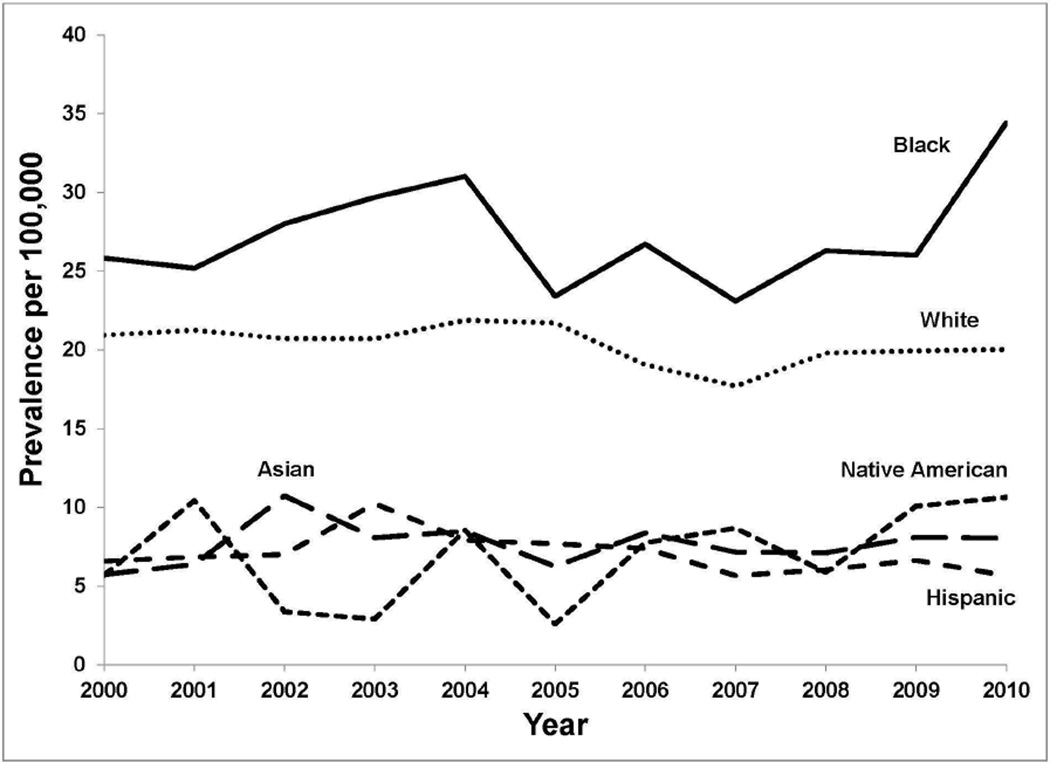

The prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 persons for diverticular bleeding decreased over the 10 year (y) period from 32.5 to 27.1 (−5.4; 95% confidence interval (CI), −5.1 to −5.7). The prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis peaked in 2008 (74.1/100,000 in 2000, 96.0/100,000 in 2008 and 91.9/100,000 in 2010). The prevalence of diverticulitis was higher in women than men, whereas women and men had similar rates of diverticular bleeding. The prevalence of diverticular bleeding was highest in Blacks (34.4/100,000 in 2010); whereas the prevalence of diverticulitis was highest in Whites (75.5/100,000 in 2010).

Conclusions

Over the past 10 y, the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis increased and then plateaued while that of diverticular bleeding decreased. The prevalence according to sex and race differed for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. These findings indicate different mechanisms of pathogenesis for these disorders.

Keywords: complications, epidemiology, prevalence, sex, race

Introduction

Complications of diverticular disease - diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding - are the leading gastrointestinal indication for hospital admission in the US. In 2009, an estimated 280,000 individuals were hospitalized for diverticular complications in the US at an aggregate cost of $2.7 billion.1

Prior studies have demonstrated a dramatic increase in the prevalence of diverticulitis from the mid 1990’s through the early part of this century.1 This increase has been most notable among young individuals.2, 3 Results from studies of trends in lower gastrointestinal bleeding, of which diverticular bleeding is the most common source, have been conflicting. A Spanish study indicated that the incidence of lower gastrointestinal bleeding is increasing, whereas a similar study in the US found a decrease in lower gastrointestinal bleeding and diverticular bleeding specifically.4, 5

Knowledge of sex and race specific rates of diverticular disease is limited particularly for diverticular bleeding. Several studies have found an overall female preponderance of diverticulitis, driven by a higher proportion of women to men in older, but not younger age groups.2, 6 In one US study, the racial distribution of diverticulitis was unchanged from 1998 to 2005 with Whites making up approximately 60% of cases in each year.2 However, prevalence rates for specific racial groups were not calculated. Little is known about the impact of sex and race on the prevalence of diverticular bleeding.

Understanding recent trends in prevalence of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding could help predict the impact of these disorders on the healthcare system and public health, and shed light on potential risk factors. Therefore, we examined trends in the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding from 2000 to 2010 using a nationally representative sample in order to provide up-to-date estimates, calculate sex and age specific rates, and directly compare trends in diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding.

Methods

Data Sources and Patient Population

We utilized the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) (Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) for the years of 2000 to 2010 to obtain prevalence estimates for hospitalization for diverticular bleeding and diverticulitis.7 Given the cross sectional nature of NIS, prevalence estimates were obtained as opposed to incidence. The NIS dataset is a nationally representative data source that captures nearly 20% of hospital discharges in the United States. Approximately 94 million discharge records were included in this analysis. We chose 2000 as the starting point of our analysis due to differences in the sampling structure of the NIS in prior years that complicate analysis of trends. The NIS contains information on demographic variables including sex, age and race (categorized as non-Hispanic White (Caucasian), non-Hispanic Black (African American), Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, or Native American). Forty states provided race/ethnicity data to HCUP for the years 2000 to 2010. Of these, 15 states reported race/ethnicity information for the entire time span with no changes to their coding structure, 17 contributed data for the entire period with coding modifications, and 8 states only partially reported.7 We used the available data without statistical adjustment (e.g. imputation) for missing values of race. We identified hospital discharges for the primary diagnosis of diverticular bleeding or diverticulitis using the International Classification of Disease-9 (ICD-9) code 562.12 (diverticular bleeding) or code 562.11 (diverticulitis without hemorrhage). Our analysis was restricted to adult hospital discharges due to the nature of the diseases under study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata MP 13.0 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) using the appropriate survey commands (svy) that specify the weighting, primary sampling unit, and strata in order to account for the sampling structure of the NIS, and ensure accurate calculation of standard errors.

We calculated age-adjusted prevalence rates for hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding using the US Census Bureau intercensal population estimates for each year from 2000 to 2010 as the denominator and the direct method of standardization.8 Prevalence rates are reported per 100,000 persons. Age was categorized into seven groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, and 80+). In addition to age-adjusted rates, we calculated age-specific rates for each age category, as well as, sex specific, and race specific rates. We also examined trends in surgical intervention for diverticulitis as a marker of severe disease using the following codes for left colon resection (ICD-9 procedure codes: 45.71, 45.75, 45.76, 45.79, 45.8, 48.62, 48.63), colostomy (ICD-9 procedure codes: 46.03, 46.1x, 48.62), or ileostomy (ICD-9 procedure codes: 46.01, 46.2x). ICD-9 codes corresponding to a concurrent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (153.2, 153.3, 154.0, 154.1, 154.2, 154.3, 154.8) were identified and those individuals excluded from the analysis. In addition, we examined the proportion of admissions for diverticulitis that were designated as non-elective admissions. In sensitivity analyses, we included discharges with an ICD-9 code 562.13 (diverticulitis with bleeding) with the primary code 562.11 for diverticulitis, and separately with 562.12 for diverticular bleeding because this code can be used to indicate either outcome. A 2 sample t-test was used to evaluate potential differences in average prevalence rates between men and women for each condition. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to assess for differences across the racial categories. A two sample test of proportions was used to determine the absolute prevalence difference between 2000 and 2010 for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. The study was exempt from institutional review board committee review due to the de-identified nature of the data.

Results

Over the 10-year study period, there were 2,151,023 hospitalizations for diverticulitis with an average of 195,548 per year (Standard Deviation (SD) 22,418). The majority of patients admitted for diverticulitis were women (58%) and White (82%). Diverticulitis was uncommon in individuals younger than 40 years of age, but was approximately equally distributed from age 40 to 80 years. (Table 1) Over the same time period, there were 780,414 hospitalizations for diverticular bleeding with an average of 70,947 per year (SD 5,638). The majority of patients admitted for diverticular bleeding were women (54%) and White (74%) and 46% were >80 years old.

Table 1.

Estimated Number of Cases and Average Age Adjusted Prevalence for Diverticular Bleeding and Diverticulitis from 2000–2010

| Diverticular Bleeding | Diverticulitis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of casesa (%) | Cases per 100,000 (SD) |

No. of casesa (%) | Cases per 100,000 (SD) | |

| Total | 780,414 (100.0) | 31.9 (3.4) | 2,151,023 (100.0) | 88.0 (7.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 361,571 (46.3) | 30.5 (2.5) | 903,460 (42.1) | 76.3 (6.9) |

| Women | 418,673 (53.7) | 33.2 (4.2) | 1,242,804 (57.9) | 98.6 (7.2) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 439,689 (74.0) | 20.3 (1.2) | 1,335,748 (82.2) | 61.8 (9.0) |

| Black | 108,524 (18.3) | 27.3 (3.4) | 115,654 (7.1) | 29.1 (6.9) |

| Hispanic | 33,210 (5.6) | 7.0 (1.3) | 153,909 (9.5) | 32.4 (6.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10,696 (1.8) | 7.7 (1.4) | 14,458 (0.9) | 10.4 (1.5) |

| Native American | 1,679 (0.28) | 7.0 (3.0) | 6,195 (0.4) | 25.8 (14.6) |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 years | 395 (0.05) | 0.1 (0.0) | 38,541 (1.8) | 7.1 (1.5) |

| 30–39 years | 3,277 (0.42) | 0.7 (0.1) | 177,063 (8.2) | 39.1 (6.0) |

| 40–49 years | 15,536 (2.0) | 3.2 (0.4) | 394,263 (18.3) | 81.1 (11.3) |

| 50–59 years | 53,087 (6.8) | 13.0 (1.8) | 465,873 (21.7) | 113.9 (8.7) |

| 60–69 years | 115,106 (14.7) | 43.5 (6.7) | 400,413 (18.6) | 151.2 (8.8) |

| 70–79 years | 234,781 (30.1) | 131.4 (16.0) | 376,512 (17.5) | 210.8 (7.7) |

| >80 years | 358,234 (45.9) | 316.6 (36.0) | 298,358 (13.9) | 263.7 (14.7) |

SD, Standard Deviation

Totals in sub-categories do not sum to total number of cases due to missing data fields

Prevalence Estimates

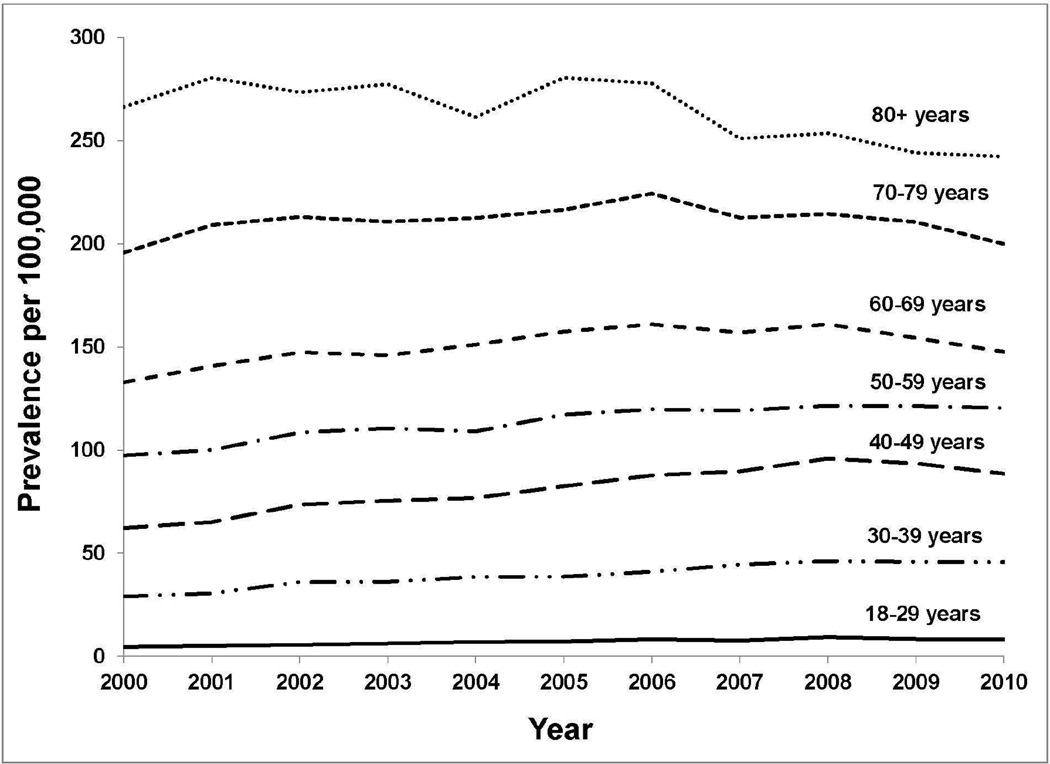

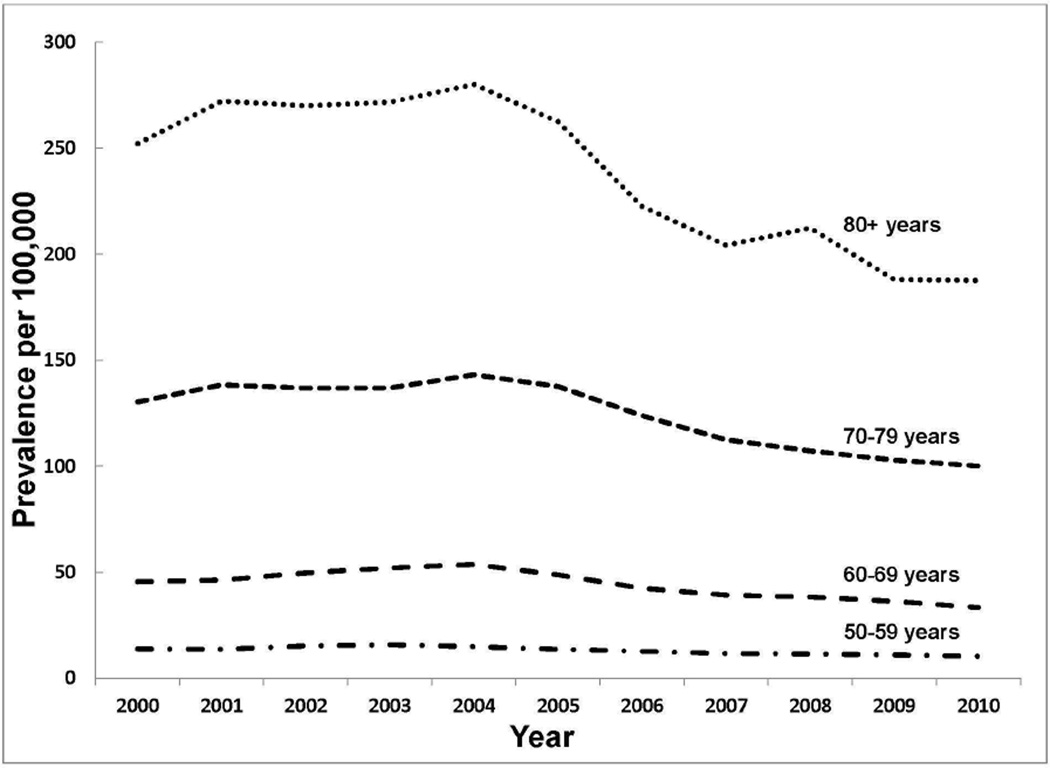

Table 1 summarizes the total number of cases and age-adjusted prevalence estimates obtained for diverticular bleeding and diverticulitis across the study period (2000–2010). The average age-adjusted prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis was approximately 3 times greater than that for diverticular bleeding (32.0 (SD) 3.4) and 88/100,000 persons (SD 7.1), respectively). The absolute prevalence difference per 100,000 for diverticular bleeding between 2000 and 2010 was 5.4 (95% confidence interval (CI), −5.1 to −5.7). For diverticulitis it was 17.8 (95% CI, 17.3 to 18.3). Diverticulitis prevalence estimates were higher than diverticular bleeding prevalence estimates for each age category until age 80 years, when diverticular bleeding estimates overtook diverticulitis prevalence estimates. (Table 1, Figures 1, 2; Supplemental Tables 1, 2)

Figure 1.

Prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 for diverticulitis by age category from 2000–2010

Figure 2.

Prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 for diverticular bleeding by age category from 2000–2010. NOTE: Prevalence estimates in the age categories <50 years were low (near zero) and stable and therefore are not shown.

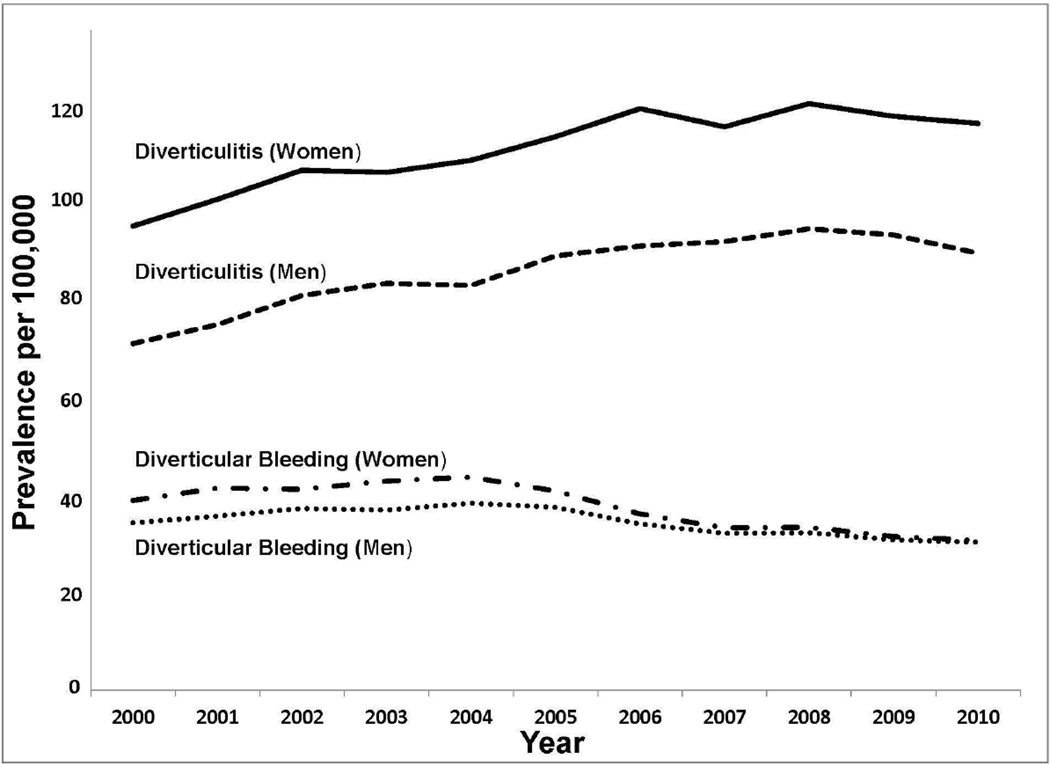

The prevalence estimates per 100,000 persons for diverticular bleeding were similar for men and women (30.5 (SD 2.5) and 33.2 (SD 4.2), respectively). However, prevalence estimates for diverticulitis were significantly higher for women compared to men (98.6 vs 76.3/100,000). (Table 1; Figure 3) This was driven by a higher prevalence of diverticulitis in women compared to men in the 50 years and older age categories. In the younger age categories, the prevalence of diverticulitis was higher among men. (Supplemental Tables 1, 2)

Figure 3.

Age adjusted prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding by sex from 2000–2010

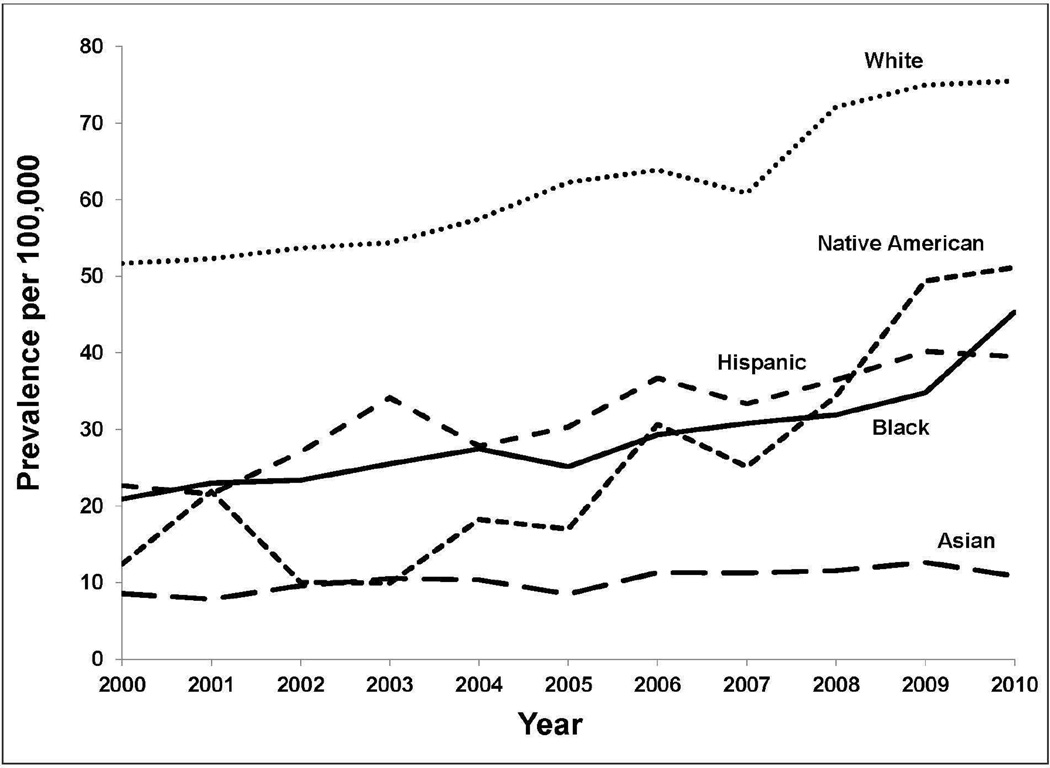

Blacks experienced the highest prevalence of diverticular bleeding, 27.3/100,000 (SD 3.4), whereas Whites experienced the highest prevalence of diverticulitis, 61.8/100,000 SD 9.0). (Table 1; Figure 4, 5)

Figure 4.

Prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 for diverticulitis by race from 2000–2010

Figure 5.

Prevalence of hospitalization per 100,000 for diverticular bleeding by race from 2000–2010

In sensitivity analyses, the addition of individuals with ICD9 code 562.13 (diverticulitis with bleeding) to the bleeding and diverticulitis groups did not significantly alter our results.

Trends

The age-adjusted prevalence per 100,000 persons of hospitalization for diverticular bleeding decreased over the study period from 32.5 in 2000 to 27.1 in 2010 (difference −5.40; 95% CI, −5.1 to −5.7). This equated to 68,269 cases in 2000 and 63,751 cases in 2010. On the other hand, the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis increased from 74.1/100,000 in 2000 to a peak of 96.0/100,000 in 2008 and was 91.9/100,000 in 2010. Diverticular bleeding decreased by a greater magnitude for men in comparison to women, and diverticulitis increased more for men in comparison to women. (Figure 3; Supplemental Tables 1, 2) The only statistically significant trend in the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticular bleeding according to racial category was a decrease for Non-Hispanic Whites (difference from 2000 to 2010 −0.9/100,000; 95% CI, −0.6/100,000 to −1.2/100,000) (Figure 5). In comparison, trends in the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis for every racial category were statistically significant and increasing. (Figure 4) From 2000 to 2010, Native Americans experienced the greatest increase in prevalence per 100,000 of hospitalization for diverticulitis (38.7; 95% CI, 35.4 to 42.0). In analyses according to decade of age, a statistically significant decrease in diverticular bleeding was seen for all age categories 40 years and older. (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 2) The prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis increased beginning with the youngest age category (18–29 years) and continued until age 70, when the prevalence plateaued (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 1).

The proportion of patients undergoing colon surgery during an admission for diverticulitis was stable at approximately 25% from 2000 to 2007, and subsequently declined to a low of 15% in 2010. Over the 10 year period, the proportion of non-elective admissions for diverticulitis ranged from 70–73% and the proportion of elective admissions from 19–21%.

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative cohort, we found that the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis increased through 2008, whereas the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticular bleeding decreased from 2004 to 2010. Diverticulitis was more prevalent than diverticular bleeding overall and across age and racial categories, except in individuals over age 80 years and Blacks from 2000–2004 where diverticular bleeding predominated. Whites had the highest prevalence of diverticulitis, whereas Blacks had the highest prevalence of diverticular bleeding.

Our findings confirm and build upon prior studies of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Several population-based studies have noted an increase in hospital discharges for diverticulitis over time beginning in the 1990’s through 2005.2, 3, 6 Our findings update these estimates through 2010 and note a peak in the prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis in 2008. Prior studies of trends in diverticular bleeding have reached conflicting results. Our findings are consistent with a US study by Laine et al that noted a decrease in prevalence beginning in 2005 in contrast to an earlier study that found a steady increase in lower gastrointestinal bleeding as a whole.4, 5 Together these findings suggest a shift in prevalence trends for hospitalization for diverticular complications that may have plateaued or begun to decline.

In contrast to prior studies that have focused on either diverticulitis or diverticular bleeding, we were able to directly compare prevalence estimates for hospitalization for these two disorders. In addition, we calculated age, sex and racial specific prevalence rates. These analyses revealed several notable differences between diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. The prevalence of both disorders increased with age. However, this was most marked for diverticular bleeding. Bleeding was uncommon prior to the 7th decade, and then increased dramatically. Although the overall prevalence of hospitalization for diverticulitis was three-times that of diverticular bleeding, the prevalence of diverticular bleeding in individuals over age 80 years was higher than any category of diverticulitis. In addition, race-specific prevalence rates differed for diverticulitis (White predominant) and diverticular bleeding (Black predominant). Indeed, Blacks were the only race in which diverticular bleeding was more prevalent than diverticulitis. Lastly, the prevalence of diverticular bleeding did not differ according to sex, whereas diverticulitis was significantly more prevalent among women. These comparative data suggest that the etiopathogenesis of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding may be different.

A number of prior studies have indicated that diverticulitis is more prevalent among women particularly in individuals older than 50 years.3, 6, 9 We also noted a female predominance particularly in older age groups. The reason for this sex difference is unknown. Diverticulosis may be somewhat more common in women.10 Alternatively, there may be differences in risk factors for diverticulitis in women versus men. Hypertension, diabetes and vascular disease have been identified as risk factors for diverticular hemorrhage.11–14 These conditions are prevalent in Blacks15, 16 and may account for the high rate of diverticular bleeding in this racial group as well as the increase in the prevalence of bleeding with age. In addition, the rise in the prevalence of diverticular bleeding with age may reflect the increasing use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatories and anti-platelets among older age groups. However, these medications, particularly non-aspirin NSAIDs, are also known risk factors for diverticulitis,17 and the prevalence of diverticular bleeding has decreased while use of these drugs is on the rise.

We saw the largest increase in prevalence of diverticulitis among Native Americans. There are few data on diverticular disease in this racial group. In one study of mortality following operative management of diverticulitis, mortality was not increased in this group compared to Whites.18 Other studies combine Native Americans with Asians or report data limited to White and Black patients.3, 19, 20 Indeed, the number of Native American individuals is proportionately small and our results for this group are less stable than for Whites and Blacks. In addition, possible differential coding of race and/or and care practices over time may have influenced the results in this group. However, Native Americans have a high prevalence of risk factors for diverticulitis including obesity, smoking and physical inactivity which could contribute to an increasing prevalence in this racial group.21 Further diverticular disease research is needed in racially diverse populations.

In this study, we used a large dataset that enabled us to examine and compare nationwide prevalence estimates for hospitalization for both diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding over time and according to age, sex and race. However, our study has several potential limitations. We relied on administrative codes to identify cases of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Prior studies indicate that administrative codes have high predictive value for diverticular disease,22 but the sensitivity of these codes is unknown. In addition, diverticular bleeding, even in clinical practice, is often a presumptive diagnosis. Therefore, our estimates may not be precise. However, there is no reason to believe that the accuracy of coding for these conditions changed over time. In addition, the coding for race in the NIS is not uniform across states and makes it difficult to distinguish Hispanic ethnicity from race. As noted above, estimates for Native Americans may be particularly unstable. Nonetheless, our findings mainly pertained to White and Black individuals, and reporting of these racial categories is likely to be most accurate.23 In addition, the high prevalence of risk factors for diverticular bleeding in Blacks and diverticulitis in Native Americans support our findings. The NIS is not a longitudinal dataset; therefore, we calculated prevalence and not incidence rates of hospitalization, and individuals with recurrent events were counted more than once. However, this would not change our estimation of the burden of these disorders. Lastly, we were only able to assess hospital events. Diverticular bleeding nearly always requires hospital care. On the other hand, mild, uncomplicated episodes of diverticulitis are often managed in the outpatient setting, and changes in prevalence of hospitalizations may reflect changes in management rather than true changes in the prevalence. To examine care practices, we looked at trends in emergent and elective admissions and found that these were stable over the 10-year period. We also examined the proportion of patients undergoing surgery during an admission for diverticulitis as a surrogate for severe disease and found a decrease beginning in 2007. These trends do not seem to indicate that a shift to outpatient management of uncomplicated disease accounts for the apparent plateau in hospital admissions for diverticulitis. Furthermore, if a shift to outpatient management were to account for an apparent plateau in hospitalizations for diverticulitis, the plateau would have been expected early in the study period.

In conclusion, we found that hospitalizations for diverticulitis rose through 2008 and then plateaued, while hospitalizations for diverticular bleeding decreased gradually after 2004. These data indicate that the impact these disorders on the hospital system may be stabilizing after a precipitous climb in the prior century. Differences in age, race and sex specific prevalence for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding suggest that these complications may have different etiopathogenic mechanisms. Our findings help lead the way to understanding the basis of these differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney R01 DK095964 and R01DK084157.

Abbreviations

- NIS

Nationwide Inpatient Sample

- OR

odds ratio

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD9

International Classification of Disease-9

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CI

confidence interval

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Chelle L Wheat, MPH-None; Lisa L Strate, MD, MPH-None

Writing Assistance: None

Author contributions:

Chelle L Wheat, MPH-formulation and study design; data assemblage; data analysis; data interpretation; manuscript writing and revision of final manuscript

Lisa L Strate, MD, MPH- formulation and study design; data assemblage; data analysis; data interpretation; manuscript writing and revision of final manuscript

References

- 1.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–1187. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RW, Jr, et al. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg. 2009;249:210–217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181952888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen GC, Sam J, Anand N. Epidemiological trends and geographic variation in hospital admissions for diverticulitis in the United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1600–1605. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laine L, Yang H, Chang SC, et al. Trends for incidence of hospitalization and death due to GI complications in the United States from 2001 to 2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1190–1195. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.168. quiz 1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Polo-Tomas M, et al. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1633–1641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang JY, Hoare J, Tinto A, et al. Diverticular disease of the colon--on the rise: a study of hospital admissions in England between 1989/1990 and 1999/2000. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1189–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(NIS). NIS Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estimates USCBNI. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/intercensal/national/nat2010.html.

- 9.Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Allen NE, et al. Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ. 2011;343:d4131. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peery AF, Barrett PR, Park D, et al. A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:266–272. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamoto T, Watabe H, Yamada A, et al. The association between arteriosclerosis related diseases and diverticular bleeding. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1161–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki K, Uchiyama S, Imajyo K, et al. Risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage: Japanese multicenter study. Digestion. 2012;85:261–265. doi: 10.1159/000336351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuruoka N, Iwakiri R, Hara M, et al. NSAIDs are a significant risk factor for colonic diverticular hemorrhage in elder patients: evaluation by a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 26:1047–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, et al. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:116–120. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltran-Sanchez H, Harhay MO, Harhay MM, et al. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999–2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferdinand KC, Rodriguez F, Nasser SA, et al. Cardiorenal metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risks in minority populations. Cardiorenal Med. 2014;4:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000357236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, et al. Use of aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases risk for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1427–1433. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broderick RC, Fuchs HF, Harnsberger CR, et al. The price of decreased mortality in the operative management of diverticulitis. Surg Endosc. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho VP, Nash GM, Feldman EN, et al. Insurance but not race is associated with diverticulitis mortality in a statewide database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:559–565. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31820d188f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lidor AO, Schneider E, Segal J, et al. Elective surgery for diverticulitis is associated with high risk of intestinal diversion and hospital readmission in older adults. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1867–1873. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1344-2. discussion 1873–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S481–S489. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erichsen R, Strate LL, Sorensen HT, et al. Positive predictive values of the International Classification of Disease, 10th edition diagnoses codes for diverticular disease in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:139–142. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldo M. Accuracy and Bias of Race/Ethnicity Codes in the Medicare Enrollment Database. Health Care Financing Review. 2004–2005;26:61–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.