Abstract

Background

Gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in the KATP channel subunits Kir6.1 and SUR2 cause Cantu syndrome (CS), a disease characterized by multiple cardiovascular abnormalities.

Objective

To better understand the electrophysiological consequences of such GOF mutations in the heart.

Methods

We generated transgenic mice (Kir6.1-GOF) expressing ATP-insensitive Kir6.1[G343D] subunits under α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter control, to target gene expression specifically in cardiomyocytes, and carried out patch-clamp experiments on isolated ventricular myocytes, invasive electrophysiology on anesthetized mice.

Results

In Kir6.1-GOF ventricular myocytes, KATP channels show decreased ATP sensitivity, but there is no significant change in current density. Ambulatory ECG recordings on Kir6.1-GOF mice reveal AV nodal conduction abnormalities and junctional rhythm. Invasive electrophysiological analyses reveal slowing of conduction and conduction failure through the AV node, but no increase in susceptibility to atrial or ventricular ectopic activity. Surface electrocardiograms recorded from CS patients also demonstrate first degree AV block, and fascicular block.

Conclusions

The primary electrophysiological consequence of cardiac KATP GOF is on the conduction system, particularly the AV node, resulting in conduction abnormalities in CS patients, who carry KATP GOF mutations.

Keywords: KATP, KCNJ8, Kir6.1, transgenic, conduction system, mouse in vivo electrophysiology, Cantu Syndrome

Introduction

Despite being the most densely expressed potassium channels in the heart1, the significance of cardiac KATP channel activity, and functional consequences of aberrant activity, remain unclear. The majority of ventricular and atrial KATP channels are generated by the pore-forming subunit Kir6.2, encoded by KCNJ11, and consistent with the notion that these channels are predominantly closed, and do not significantly contribute to cell excitability under normal conditions, no major electrophysiological derangements are apparent in Kir6.2−/− mice2, nor are there any reports of cardiac electrophysiological abnormalities in humans with either congenital hyperinsulinism or neonatal diabetes, which result from loss-of-function (LOF) or gain-of-function (GOF) Kir6.2 mutations, respectively3.

KCNJ8 encodes a second pore-forming Kir6.1 subunit4. KATP channels formed from Kir6.1 subunits have a lower conductance than Kir6.2-dependent channels and may be less sensitive to ATP inhibition, but more dependent on ADP activation5,6. While Kir6.1 is not a major component of the sarcolemmal KATP in bulk myocardium7, there are reports of KATP channels with low single channel conductance, characteristic of Kir6.1 channels, as well as direct evidence of Kir6.1 expression, in the conducting system8,9. Cantu Syndrome (CS) is a rare multi-organ disease, characterized by hypertrichosis, persistent ductus arteriosus, cardiomegaly, and skeletal abnormalities10. ABCC9, which encodes the predominant sulfonylurea receptor (SUR2) isoform in the cardiovascular system, have been identified in 18 of 25 individuals with CS11,12. Two studies13,14 have also identified KCNJ8 mutations in CS patients. The demonstration that CS can result from mutations in Kir6.114 or SUR2 confirms that CS results from GOF in KATP channels formed from these subunits.

Cardiac electrophysiological abnormalities have not yet been reported for CS patients. To assess consequences of KATP channel GOF in the heart we have carried out electrophysiological studies in mice expressing Kir6.1-GOF mutations specifically in cardiac myocytes and throughout the central conduction tissue, as well as non-invasive ECG studies in humans with CS.

Methods

Generation of transgenic mice

All procedures complied with the standards for the care and use of animal subjects as stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 2001) and were reviewed and approved by the Washington University Animal Care and Use Committee. CX1-Kir6.1[G343D] transgenic mice were generated as described previously15. To direct cardiac-specific Kir6.1 [G343D] expression, we crossed CX1-Kir6.1[G343D] transgenic mouse with mouse carrying α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC) promoter driving CRE recombinase expression (Jackson Laboratory). Kir6.1-GOF transgene will express in the heart of CX1-Kir6.1[G343D]/αMHC-Cre double transgenic (DTG) mice.

Cellular electrophysiological recordings

The isolation of mouse cardiomyocytes followed previously described protocols16. Patch-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Signals were processed through an analogue with 4-pole low pass Bessel filter set at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz using pCLAMP 8 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All recordings were obtained at room temperature. Isolated myocytes perfused with bath solution containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 3 NaHCO3, 0.2 NaH2PO4, 5 HEPES, and Glucose (pH 7.40); and pipettes had resistances of 1.5–2.5 MΩ when filled with pipette solution containing (in mM) 130 K-aspartate, 20 KCl, 4 K2HPO4, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 EGTA, 0.1 K2ATP, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.20). For excised inside-out patch-clamp recording, pipette and extracellular solutions contained Kint containing (in mM) 40 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 1 K2-EDTA, and 4 K2HPO4 (pH 7.40).

Mouse echocardiography and ambulatory electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring

Mouse echocardiography and ambulatory ECG recordings were made essentially as described previously17,18. ECG signals were reviewed and analyzed using both Clampfit 9 (Molecular Devices) as well as custom programmed software (AN Lopatin, University of Michigan).

In vivo mouse electrophysiology testing with programmed electrical stimulation

Protocols for in vivo mouse electrophysiology studies have been previously described in detail19 in animals anesthetized with 2.5% Avertin (10 ml/kg, i.p.). Surface ECG intervals were measured in 6-limb leads by 2 experienced, independent observers blinded to the animal’s genotype.

Analysis of CS patients

Electrocardiograms were obtained from CS patients as part of a research clinic established at Washington University and Children’s Hospital (http://cantu-syndrome.org/). Each patient or legal guardian signed an informed consent form to undergo non-invasive testing and molecular evaluation. All studies were approved by the Internal Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine. Resting standard 12-lead ECG and Holter monitoring were obtained in all individuals. Blood samples were collected for genetic investigations. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using a standard enzymatic phenol-chloroform method. Open reading frames of ABCC9 were analyzed by direct sequencing after PCR amplification.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (S.E.M.) with n being the number of, animals, cells or patches in excised patch clamp experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student t-test. Statistic significance was set as P < 0.05.

Results

Generation of cardiac-specific Kir6.1-GOF transgenic mice

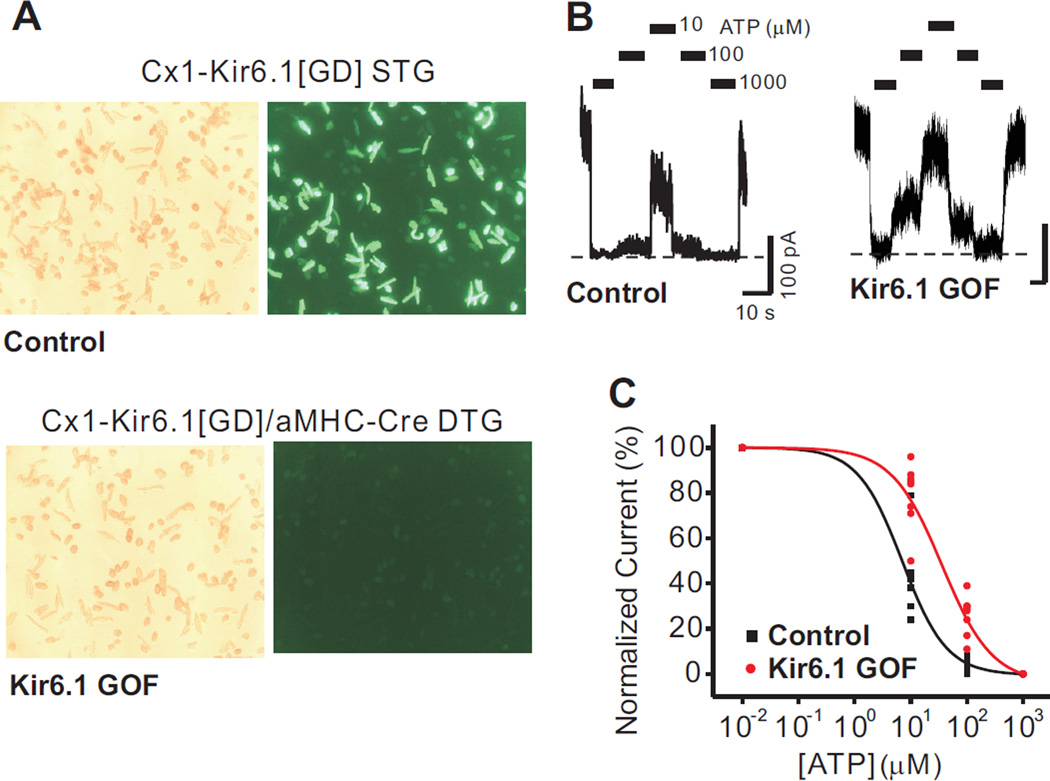

Mice carrying the CX1-Kir6.1[G343D] transgene have been previously described15. In the absence of Cre-recombinase, eGFP protein is constitutively and ubiquitously expressed in these mice20, but is substantially decreased in double transgenic (DTG) mice (Kir6.1-GOF) which additionally carry the αMHC-Cre recombinase transgene, resulting in excision of the floxed eGFP cassette and expression of the Kir6.1[G343D] transgene (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Reduced sensitivity of cardiac KATP channels to ATP inhibition in Kir6.1-GOF ventricular myoctes. A) Isolated cardiomyocytes from CX1-Kir6.1[G343D] STG mice fluoresced green, whereas cardiomyocytes from CX1-Kir6.1[G343D]/α-MHC-Cre DTG (Kir6.1-GOF) mice were dark. B) Excised inside-out patch recordings from control and Kir6.1-GOF cardiomyocytes. Bars indicate where different ATP concentrations were applied, and the dashed line represents zero current. C) ATP-sensitivity from cumulated data is best fit by Hill equation with IC50 values of 14 µM for control and 44 µM for Kir6.1-GOF, and Hill coefficient of 1.6 for control and 1.2 for Kir6.1-GOF.

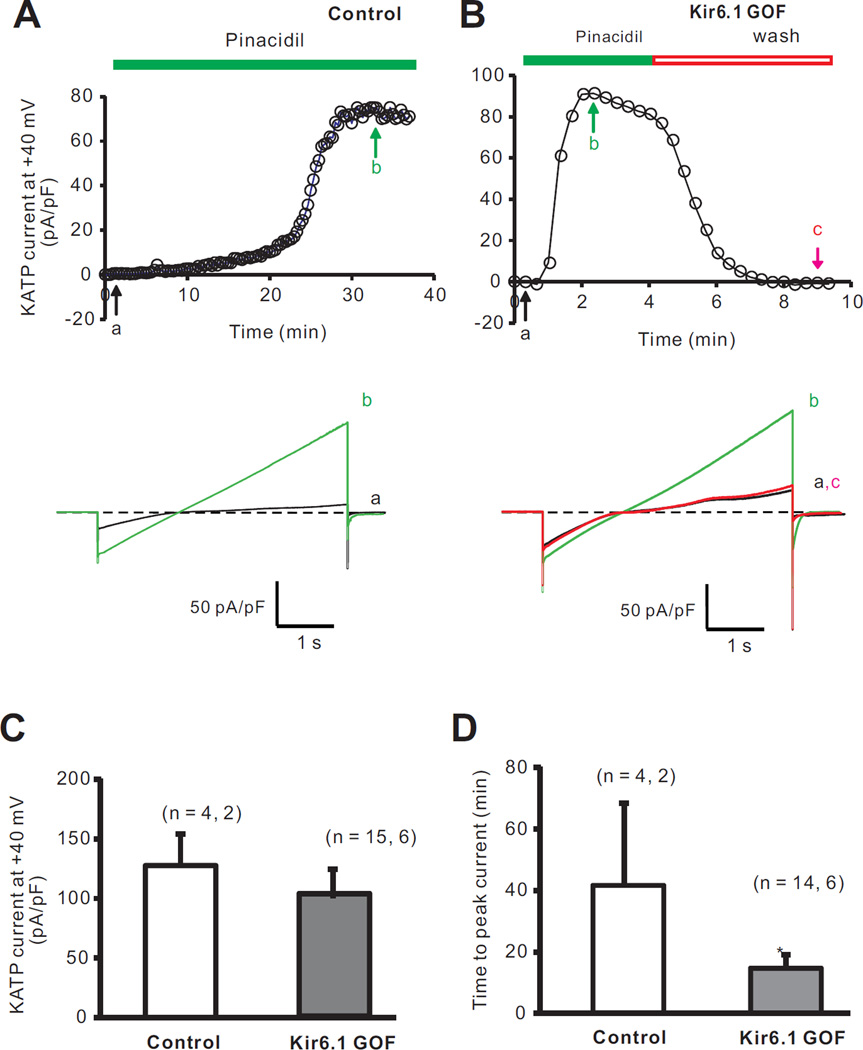

In recombinant expression, the Kir6.1[G343D] mutation reduces ATP-sensitivity of expressed KATP channels20. Consistent with substantial incorporation of mutant subunits into sarcolemmal KATP channels, ATP-sensitivity was reduced in isolated membrane patches from Kir6.1-GOF ventricular myocytes (Figure 1A,B); with shifted ATP-response curves (Figure 1C). Mean current in excised patches was not significantly different between the two groups (85 ± 18 pA in control versus 88 ± 14 pA in Kir6.1-GOF), implying that mutant Kir6.1 subunits incorporated into sarcolemmal KATP channels without markedly affecting net channel density. In whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings (Figure 2A–D), neither cell capacitance nor pinacidil-activated whole-cell KATP current density (Figure 2C) was significantly different between Kir6.1-GOF and control myocytes, but the time to peak current following pinacidil application (Figure 2D) was significantly lower in Kir6.1-GOF myocytes (15 ± 4 min) compared to control myocytes (41 ± 15 min, p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of ventricular myocyte KATP currents from control and Kir6.1-GOF mice. A) Time courses of KATP activation by 100 µM pinacidil from a control myocyte (Top), and full current traces recorded at time points indicated (Bottom). B) Time courses of whole-cell KATP currents activated by 100 µM pinacidil from a Kir6.1-GOF myocyte (Top), and full current traces recorded at the time points indicated (Bottom). C) Summarized peak pinacidil-activated KATP currents measured (at +40 mV). D) Summarized data of time to fully open KATP channels in pinacidil. *p<0.05 by two-tailed student T-test.

Conduction abnormalities in Kir6.1-GOF mice

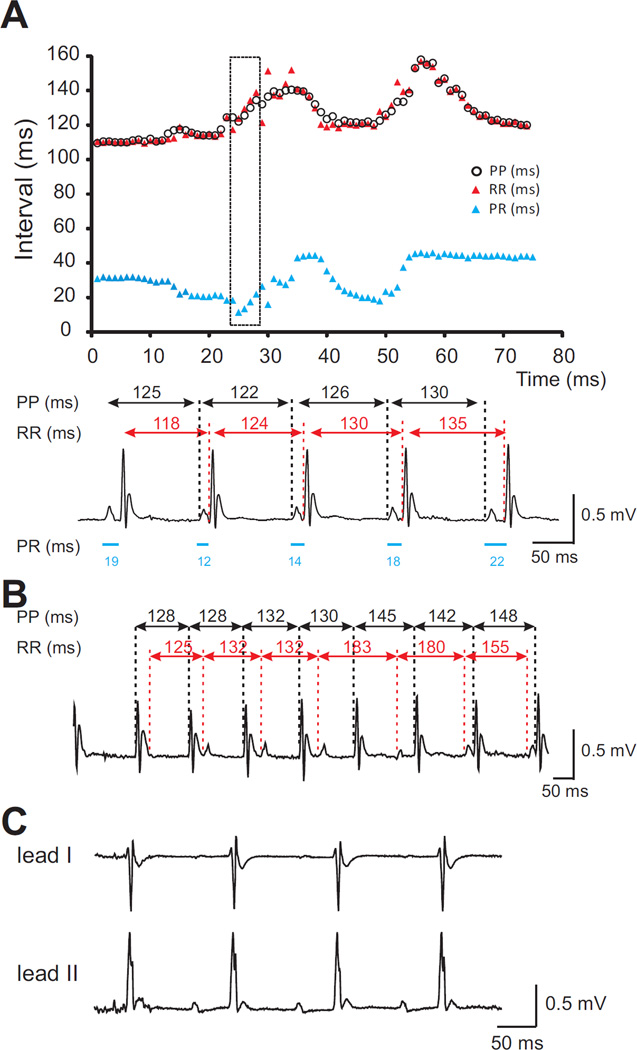

Representative daytime (12:00 pm) and nighttime (12:00 am) ambulatory ECG recordings samplings were analyzed for each group at identical time points (Supplementary Table 1). No significant abnormalities were recorded in Kir6.1-GOF animals, except for an apparently shorter night-time mean PR interval in the Kir6.1-GOF animals. However, marked variability in the measured PR interval, reflective of a combination of failure of conduction from atria through the AV node and junctional rhythm was detected in 3 of 6 Kir6.1-GOF mice, while none of 6 control mice showed any comparable abnormality. Episodes of junctional rhythm, in which the junctional rate is slightly more rapid than the sinus rate were also seen in Kir6.1-GOF (Figure 3A,B). The striking mis-match between PP intervals and RR intervals in Figure 3A reflects maintenance and/or acceleration of a junctional rate in the presence of marked slowing of the atrial rate. This is consistent with the tendency towards lengthening of the sinus node recovery time in anesthetized animals (see below). Also apparent in some Kir6.1-GOF recordings, though not evident in averaged data (Supplementary Table 1), was a particularly broad QRS complex (Figure 3C). This may be reflective of occasional intraventricular conduction delay, similar to fascicular block seen in ECGs from CS patients (see below).

Figure 3.

ECG analyses from ambulatory unanesthetized Kir6.1-GOF mice. A) Relationship between PP, RR, and PR intervals from Lead II recording of one Kir6.1-GOF mouse. PR and RR intervals varied. The trace was analyzed in detail for the segment in the black box (bottom), showing how the relationship between the P wave and QRS complex is changing. B) More dramatic discordance between PP and PR intervals in another Kir6.1-GOF mouse. C) Apparent QRS broadening evident in lead II recording from a different Kir6.1-GOF mouse.

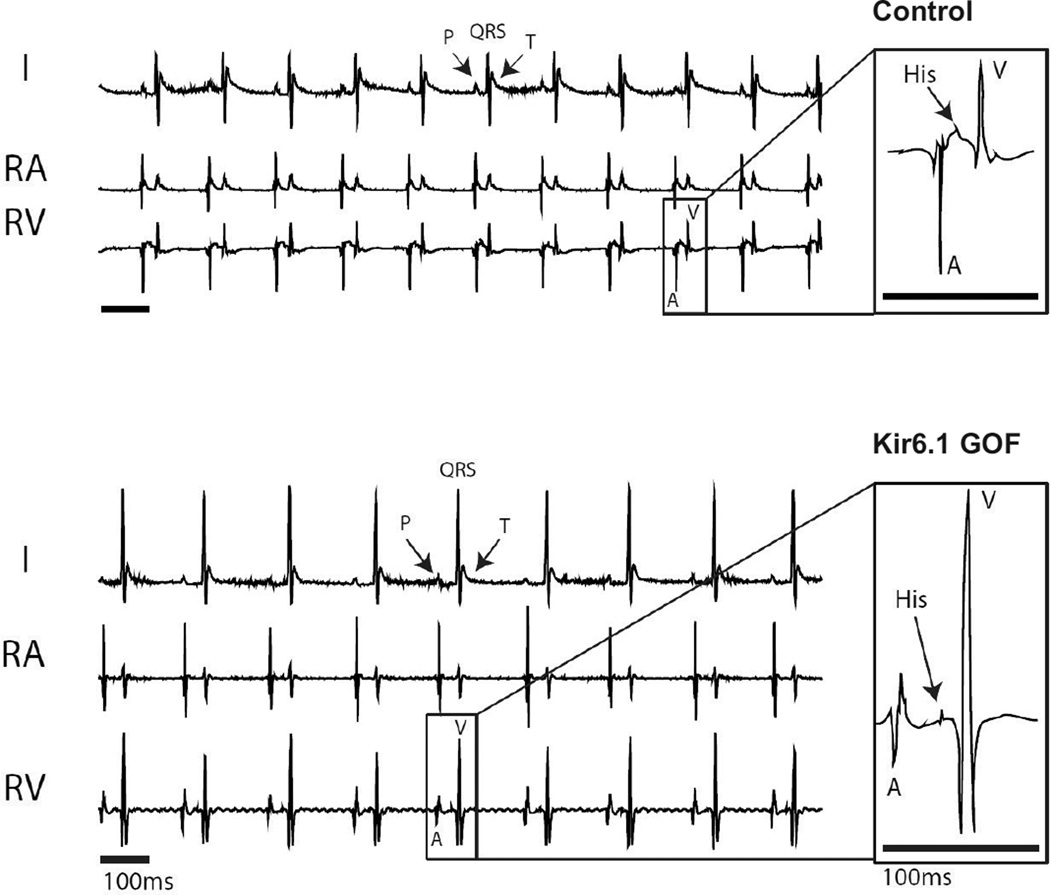

To further characterize the conduction system and to assess arrhythmia susceptibility, we performed in vivo electrophysiological analysis using intracardiac recordings of anesthetized Kir6.1-GOF and sex-matched littermate control mice at 3 months of age (Figure 4). A His signal was detectable in all but one of ten experimental animals, and in all control animals. There was no difference in sinus cycle length (SCL), His duration (H), or His-ventricular interval (HV), between Kir6.1-GOF and control mice (Supplementary Table 2). However the time between the onset of the atrial electrogram (A) and the onset of the His signal (AH) tended to be longer in the Kir6.1-GOF mice, with the overall atrio-ventricular interval (AVI) being significantly prolonged in the Kir 6.1 GOF. Programmed electrical stimulation (PES) was performed to determine tissue refractoriness and arrhythmia inducibility. Effective refractory periods (ERP) were measured in the atria (AERP), AV node (AVERP) and ventricle (VERP). Figure 5 shows representative examples of AVERP determination. A train of 8 stimuli (S1) was delivered with cycle length of 100 ms, followed by additional stimulus (S2) at a cycle length shorter than the drive train. In the control mouse, S2 (S1–S2 = 60 ms) resulted in a subsequent V (capture), but, the same stimulus resulted in surface P, but no ventricular V (missed) signal in Kir6.1-GOF, reflecting enhanced refractoriness of the Kir6.1-GOF AV node (Supplementary Table 2). While the effective refractory period (ERP) was not different between genotypes in the atrial and ventricular muscle, it was dramatically longer in Kir6.1-GOF AV node compared to controls. Thus, while the αMHC promoter drives transgene expression throughout the atrium, AV node, and ventricle, ERP differences only in the AV node itself, implicateds sensitivity of this region to KATP GOF.

Figure 4.

Baseline surface ECG and intracardiac electrogram recordings from anesthetized control and Kir6.1-GOF mice. Lead I surface ECG (I), along with intracardiac signals from right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV) are shown. Note atrial electrogram (A) corresponds to the P wave in surface ECG, and the ventricular electrogram (V) corresponds to the QRS complex. His electrograms are shown in the inset.

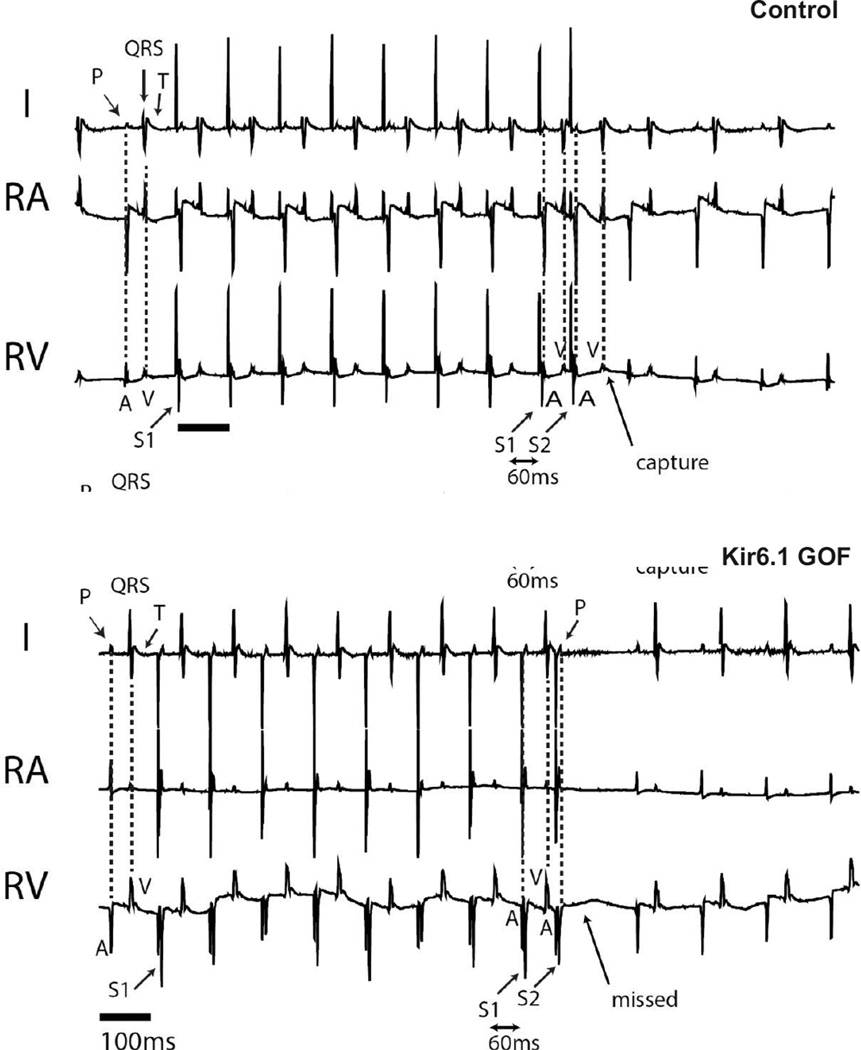

Figure 5.

Atrio-ventricular (AV) effective refractory period (ERP) determination using right atrial pacing in control and Kir6.1-GOF mice. AVERP determination was made using an 8 beat drive train of 100 ms (S1), followed by a single atrial (A) extra-stimulus (S2) that was progressively shortened by 10 ms until an atrial stimulus failed to result in a ventricular electrogram (V). Identical pacing protocol was performed in both control and Kir6.1-GOF mice. S2 resulted in ventricular capture (V) in control mouse, but failed to conduct to ventricles (missed) in the Kir6.1-GOF mouse.

Diminished AV node conduction in Kir6.1-GOF AV node

SA and AV node response to pacing was also assessed (Supplementary Table 3). Multiple measures consistently demonstrated diminished conduction through the AV node in Kir6.1-GOF. Figure 6 demonstrates surface (lead I) and intracardiac (RA, RV) recordings in response to right atrial pacing at 80 ms for control and Kir6.1-GOF mice. In the control recording, each atrially paced beat (S1, stimulus artifact) results in atrial capture – seen by P wave on surface lead and A wave on intracardiac lead. Furthermore, each atrial (A) electrogram results in one ventricular (V) electrogram after a constant AV interval of 80 ms (Figure 6). By contrast, the same pacing protocol in Kir6.1-GOF mouse results in single atrial and ventricular electrograms, but the AVI progressively increases until a beat fails to conduct through to the ventricle (Wenckebach conduction).

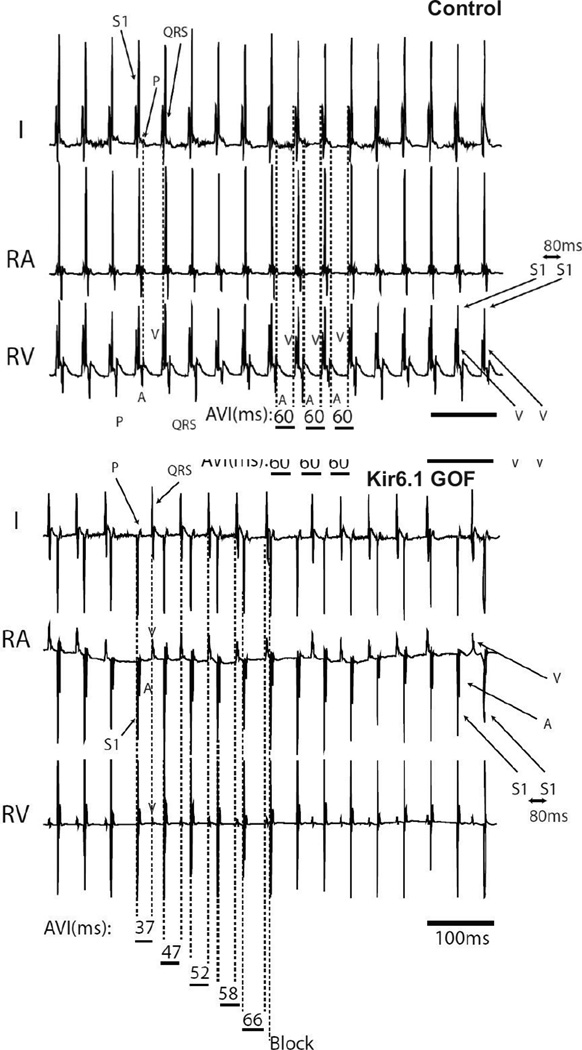

Figure 6.

AV nodal conduction assessment using continuous right atrial (RA) pacing in control and Kir6.1-GOF with continuous RA pacing at a paced cycle length (PCL) of 80 ms. In the control mouse, continuous pacing (S1) at a PCL of 80 ms results in 1:1 conduction through the AV node (i.e. for every one atrially paced beat, one ventricular electrogram is recorded with an unchanging atrio-ventricular (AV) interval (AVI = 60 ms). By contrast, the identical protocol delivered in the Kir6.1-GOF mouse heart results in Wenckebach conduction (progressively lengthening of AVI until atrial paced beat (A) fails to elicit a ventricular electrogram (V).

Figure 7 depicts representative response to atrial pacing at a shorter (60 ms) cycle length. While this now results in Wenckebach conduction in control, there is now 2:1 atrial to ventricular conduction in the Kir6.1-GOF, again implying diminished conduction in response to the identical stimulus. In Kir6.1-GOF, all three measures of anterograde conduction were significantly prolonged (Supplementary Table 3), reflecting diminished AV nodal conduction. There was no statistically significant change in retrograde AV conduction in Kir6.1-GOF animals. Using programmed stimulation with single, double, and triple extra-stimuli as well as burst pacing, neither control, nor Kir6.1-GOF mice generated atrial or ventricular arrhythmias (data not shown).

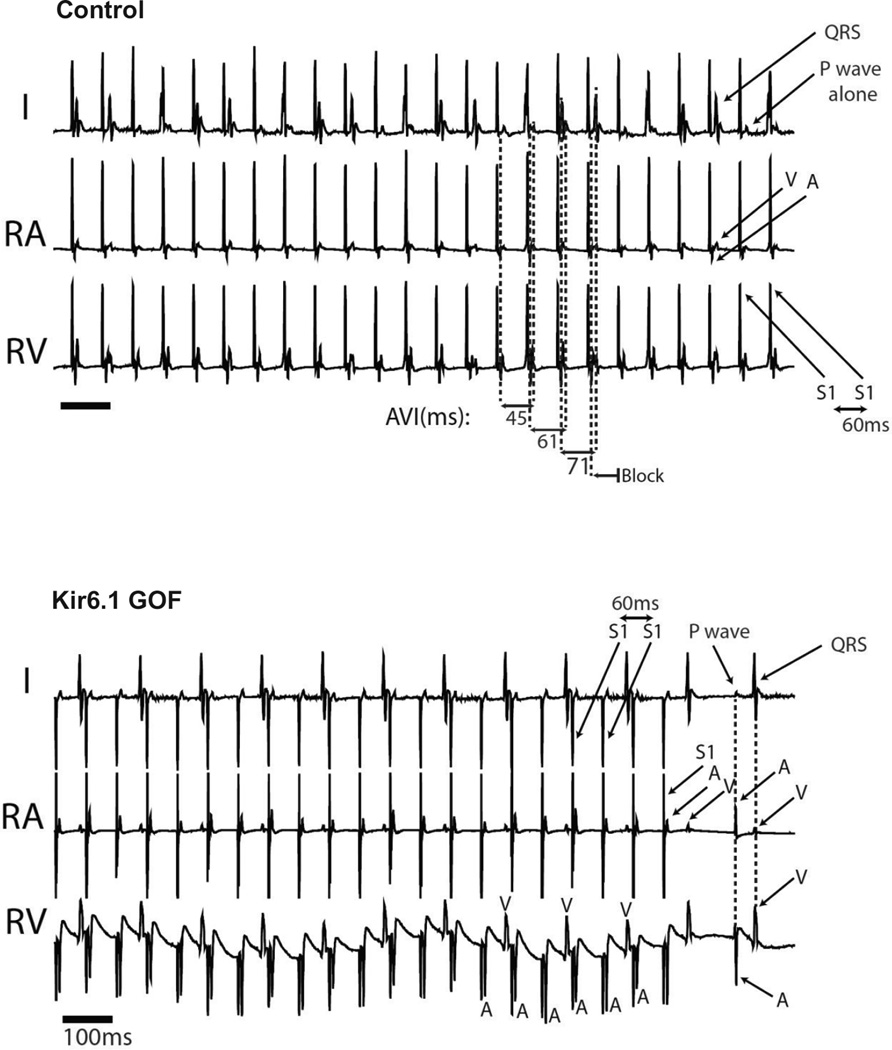

Figure 7.

AV nodal conduction assessment using continuous right atrial (RA) pacing in control and Kir6.1-GOF as in Figure 7, but with continuous RA pacing at a paced cycle length (PCL) of 60 ms. While RA pacing at 60 ms in control mice resulted in Wenckebach conduction, the identical protocol in Kir6.1-GOF mice resulted in 2:1 conduction through the AV node.

Cantu Syndrome patients demonstrate PR prolongation and fascicular block on surface electrocardiogram

Given the conduction abnormalities in mice harboring KATP GOF mutations, electrophysiological consequences in genetically identified Cantu Syndrome patients with ABCC9 mutations were evaluated. Under resting conditions, patient ECGs demonstrated variable T-wave flattening and T-wave inversions (Figure 8A,B), but no evidence of QT shortening. Several consistent features emerge. First, four of ten CS patients showed longer PR intervals than average (>98th percentile for age, Figure 8B, Supplementary Table 4). Two of 10 CS patients also demonstrated fascicular conduction defects, one with left posterior fascicular block, and one with left anterior fascicular block (Figure 8A). One of the ten patients demonstrated what might be classified as a ‘J-wave’ notch, although given the controversy as to what qualifies as a pathologic ‘J-wave’21, the relevance of this notch is unclear. No patients had symptoms or history consistent with syncope or abortive sudden death.

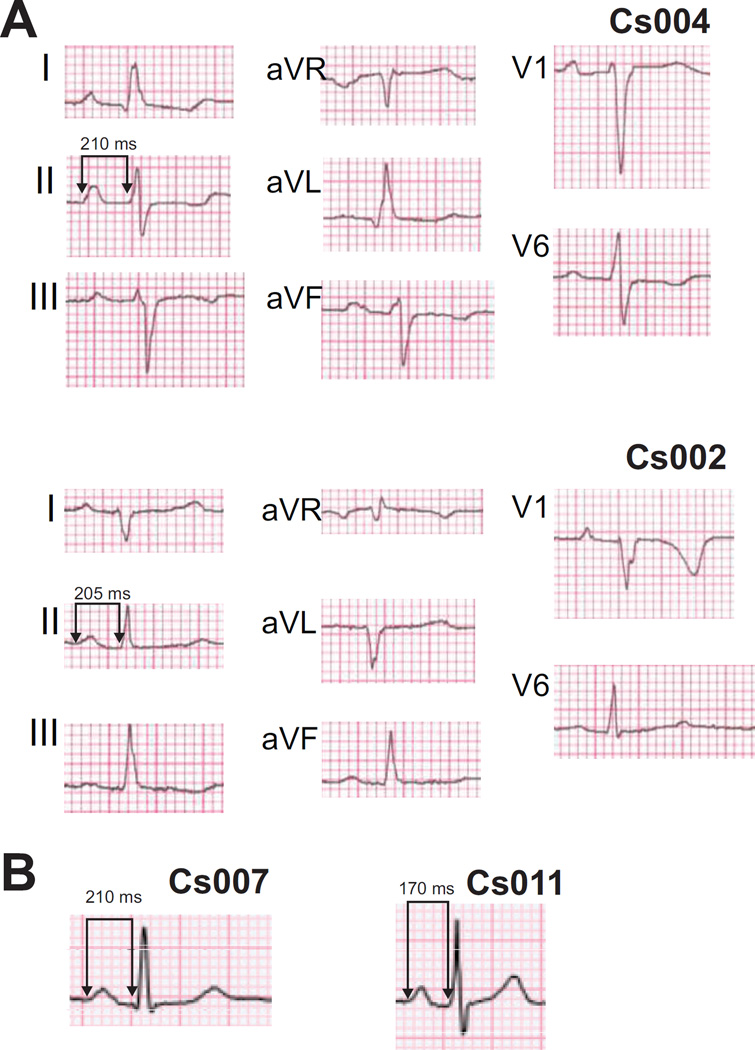

Figure 8.

Surface ECG from CS patients display fascicular block and prolonged PR intervals. A) CS patient ECGs showing left anterior fascicular block (left axis deviation and conduction delay in lead V1, patient Cs004) and left posterior fascicular block (right axis deviation and conduction delay in lead V1, patient Cs002). All ECG’s were recorded using standard settings (10 mm/mV and 25 mm/s). B) Lead II recordings showing isolated PR prolongation in additional adult (Cs007) and pre-adolescent (Cs011) patients (see also Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

To explore electrophysiological consequences of KATP channel GOF and potentially inform electrophysiological consequences in Cantu syndrome, we generated cardiac-specific Kir6.1-GOF transgenic mice expressing ATP-insensitive Kir6.1[G343D] subunits20 throughout the myocardium and the conducting system22. We observed decreased sensitivity to ATP inhibition of the KATP channel in Kir6.1-GOF ventricular cardiomyocytes, resulting in faster development of KATP current under activating conditions, but no obvious QT shortening, consistent with no significant activation in the bulk myocardium. However, both ambulatory and invasive studies revealed abnormal AV nodal conduction. Consistent with a localized sensitivity to KATP GOF in the AV node, but minimal effects on atrial or ventricular excitability or repolarization, ambulatory ECG recordings on CS patients also revealed PR lengthening and fascicular block.

Relative insensitivity of the heart to KATP GOF

KATP channels couple metabolism to excitability, opening, and hence reducing excitability, under conditions of depressed [ATP]/[ADP]23. They are formed as octamers of 4 Kir6.x pore-forming subunits plus 4 SURx subunits23. One pair of subunits (Kir6.2 and SUR1) are predominantly expressed in neurohormonal cells, and GOF mutations in Kir6.2 and SUR1 are the major cause of neonatal diabetes mellitus (NDM) in humans24. However, cardiac overexpression of either SUR1 or Kir6.2 gain-of-function mutations results in no obvious pathology25,26, consistent with no reported cardiac electrophysiological abnormalities in NDM patients.

ABCC8 (SUR1) and KCNJ11 (Kir6.2) are immediately adjacent genes on chromosome 11 (in humans), whereas ABCC9 (SUR2) and KCNJ8 (Kir6.1) are immediately adjacent genes on chromosome 12. NDM results from GOF mutations in the first pair, whereas Cantu Syndrome results from mutations in the second pair, and there are no overlapping symptoms between the two syndromes. This suggests non-overlapping and exclusive co-regulation and co-location of expression of each pair of genes. Anomalously, the non-canonical Kir6.2 plus SUR2A combination generates the major constituents of the sarcolemmal KATP in ventricular myocardium26. The KATP channel density in the myocardium is very high, and when fully activated, is sufficient to essentially abolish the action potential27. Given this potentially catastrophic consequences of KATP activation in the bulk myocardium it is therefore tempting to speculate that the heart employs specific regulatory mechanisms that keep the canonical (Kir6.1/SUR2, or Kir6.2/SUR1) subunit pairings from occurring in the bulk of the myocardium, and instead forces the Kir6.2/SUR2 combination specifically to avoid marked KATP activation.

Why is the conduction system affected by Kir6.1-GOF?

There are also multiple reports of KATP channels with low single channel conductance – consistent with Kir6.1 acting as a pore-forming component – as well as direct evidence of Kir6.1 expression, in the conducting system8,9, most likely combined with SUR2. When crossed with mice expressing αMHC-Cre, the Kir6.1[G343D] GOF transgene will be expressed throughout the myocardium, including the SA and AV nodes22,28. In Kir6.1-GOF, ventricular myocyte KATP channels demonstrate diminished ATP sensitivity (Figure 1), but there is no evidence of basal KATP activity in intact cells, nor any QT shortening in the intact heart. However, we find consistent evidence of AV node dysfunction in both Kir6.1-GOF mice and in humans with CS. Ambulatory ECGs demonstrate that, like Kir6.2 GOF or SUR1 overexpressing mice25,26, Kir6.1-GOF mice have central conduction system abnormalities. The morphology of the P and QRS waves was generally similar in Kir6.1-GOF mice and littermate controls, suggesting that the origin for atrial beats remains the SA node, and that ventricular excitation is via the AV node, although occasional evidence of QRS lengthening (Figure 3C) suggests slowed conduction through the His-Purkinje system. In some Kir6.1-GOF records, a seemingly marked PR shortening (Figure 3A,B), which might naively indicate accelerated conductance through the AV node, is revealed to result from the RR interval being shorter than the coincident PP interval, such that the P wave gradually runs into the QRS wave and is eventually embedded in the QRS and undetectable on the ECG. Thus the correct explanation is that the SA node functions as the pacemaker for the atria, which results in a normal P wave, but slowed conduction into the AV node allows an ectopic junctional pacemaker located between the AV node and the start of the His bundle branches to drive the apparently associated QRS wave, i.e. a junctional rhythm.

The AV node may thus be a ‘hotspot’ of sensitivity to KATP overactivity. This is supported by studies with KATP channel opening drugs, in which PR prolongation has been observed29,30. Activation would then lead to slowed conduction in the node, and enhanced pacemaking below the node itself, which could result from KATP-induced shortening of the APD and hence reduced refractoriness.

Cantu Syndrome electrophysiologic abnormalities

We report the first evidence of cardiac electrophysiologic abnormalities in CS patients. Slowed AV nodal conduction and fascicular block are consistent with our findings in mice, but it is important to note that the ECG findings in the patients are made in only a small number of patients, each of whom carried ABCC9 (SUR2) mutations (not KCNJ8, Kir6.1) and although essentially all reported features of the disease seem to be common to patients with either gene mutated13,14 we have not carried out similar studies on KCNJ8 patients. It should be noted that several studies have also reported a specific Kir6.1 variant (S422L) to be associated with ‘Jwave’ or ‘early repolarization’ syndrome (ERS), characterized by abnormalities in the J-point of the electrocardiogram31,32. We see no evidence of either clinical symptomatology or pathologic ‘J-waves’ in CS electrocardiograms, and no CS features have thus far been reported in ERS patients, so at this point it remains unclear how or whether these two clinical pathologies are related. From our studies to date, we cannot rule out the possibility that the PR interval changes and other abnormalities we see in CS patients or in animals could be secondary to developmental cardiac abnormalities or altered autonomic activity, rather than a direct effect of altered channel activity.

Given the multiple organ morbidities associated with CS, it is likely that in the near future CS patients will be treated with sulfonylureas or other KATP channel blocking drugs, as has proven very successful for treatment of neonatal diabetes caused by mutations in ABCC8 and KCNJ1133. Because of the action of sulfonylureas on Kir6.2/SUR1-dependent KATP channels, it will be necessary to minimize the potential for hypoglycemia in CS patients, and so Kir6.1-specific KATP channel inhibitors34 may be important to consider. Reversal of the cardiac electrical abnormalities that we report may be important markers of drug action, as well as potentially important therapeutic consequences.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

(1) What new medical knowledge is presented in your manuscript? The manuscript describes the consequences of deliberate overexpression of a potassium channel subunit in the mouse heart. Extrapolation from this model to humans is difficult but the implications of the study are that the conduction system is likely to be sensitive to the effects of KATP channel overactivity. Accordingly, we show, for the first time, that in Cantu Syndrome patients with a KATP channel GOF mutation, AV conduction appears to be the major consequence. (2) How can this medical knowledge help improve patient care? These findings will be useful when considering potential pharmacological therapies in Cantu Syndrome. (3) What steps should be taken to translate your discoveries into clinical practice? Further electrocardiological studies of Cantu Syndrome patients are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We authors would like to acknowledge Kathryn Yamada and Attila Kovacs in the Washington University Mouse Phenotyping core for performing echocardiography and telemetry implantation, as well as Richard Schuessler for assistance and providing the equipment necessary to perform In vivo electrophysiology.

Funding sources This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 HL45742 (to CGN) and K08 HL94748 to MDL.

Abbreviations

- GOF

Gain-of-function

- LOF

Loss-of-function

- CS

Cantu Syndrome

- α-MHC

α-myosin heavy chain

- AV

atrio-ventricular

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- SUR

Sulfonylurea receptor

- Kir

Inward rectifier potassium channel

- DTG

Double transgenic

- eGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Lederer WJ, Nichols CG. Nucleotide modulation of the activity of rat heart ATP- sensitive K+ channels in isolated membrane patches. Journal of Physiology. 1989;419:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki M, Li RA, Miki T, Uemura H, Sakamoto N, Ohmoto-Sekine Y, Tamagawa M, Ogura T, Seino S, Marban E, Nakaya H. Functional roles of cardiac and vascular ATP-sensitive potassium channels clarified by Kir6.2-knockout mice. Circulation research. 2001;88:570–577. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inagaki N, Inazawa J, Seino S. cDNA sequence, gene structure, and chromosomal localization of the human ATP-sensitive potassium channel, uKATP-1, gene (KCNJ8) Genomics. 1995;30:102–104. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang HL, Bolton TB. Two types of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in rat portal vein smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beech DJ, Zhang H, Nakao K, Bolton TB. K channel activation by nucleotide diphosphates and its inhibition by glibenclamide in vascular smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;110:573–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babenko AP, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Reconstituted human cardiac KATP channels: functional identity with the native channels from the sarcolemma of human ventricular cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:1132–1143. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao L, Kefaloyianni E, Lader J, Hong M, Morley G, Fishman GI, Sobie EA, Coetzee WA. Unique properties of the ATP-sensitive K channel in the mouse ventricular cardiac conduction system. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:926–935. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Light PE, Cordeiro JM, French RJ. Identification and properties of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in myocytes from rabbit Purkinje fibres. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:356–369. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols CG, Singh GK, Grange DK. KATP channels and cardiovascular disease: suddenly a syndrome. Circ Res. 2013;112:1059–1072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Bon BW, Gilissen C, Grange DK, Hennekam RC, Kayserili H, Engels H, Reutter H, Ostergaard JR, Morava E, Tsiakas K, Isidor B, Le Merrer M, Eser M, Wieskamp N, de Vries P, Steehouwer M, Veltman JA, Robertson SP, Brunner HG, de Vries BB, Hoischen A. Cantu syndrome is caused by mutations in ABCC9. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harakalova M, van Harssel JJ, Terhal PA, van Lieshout S, Duran K, Renkens I, Amor DJ, Wilson LC, Kirk EP, Turner CL, Shears D, Garcia-Minaur S, Lees MM, Ross A, Venselaar H, Vriend G, Takanari H, Rook MB, van der Heyden MA, Asselbergs FW, Breur HM, Swinkels ME, Scurr IJ, Smithson SF, Knoers NV, van der Smagt JJ, Nijman IJ, Kloosterman WP, van Haelst MM, van Haaften G, Cuppen E. Dominant missense mutations in ABCC9 cause Cantu syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:793–796. doi: 10.1038/ng.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brownstein CA, Towne MC, Luquette LJ, Harris DJ, Marinakis NS, Meinecke P, Kutsche K, Campeau PM, Yu TW, Margulies DM, Agrawal PB, Beggs AH. Mutation of KCNJ8 in a patient with Cantu syndrome with unique vascular abnormalities - Support for the role of K(ATP) channels in this condition. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56:678–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper PE, Reutter H, Woelfle J, Engels H, Grange DK, van Haaften G, van Bon BW, Hoischen A, Nichols CG. Cantu syndrome resulting from activating mutation in the KCNJ8 gene. Human mutation. 2014;35:809–813. doi: 10.1002/humu.22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li A, Knutsen RH, Zhang H, Osei-Owusu P, Moreno-Dominguez A, Harter TM, Uchida K, Remedi MS, Dietrich HH, Bernal-Mizrachi C, Blumer KJ, Mecham RP, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Hypotension Due to Kir6.1 Gain-of-Function in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e000365–e000365. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flagg TP. Remodeling of excitation-contraction coupling in transgenic mice expressing ATPinsensitive sarcolemmal KATP channels. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;286:H1361–H1369. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00676.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Razani B, Zhang H, Schulze PC, Schilling JD, Verbsky J, Lodhi IJ, Topkara VK, Feng C, Coleman T, Kovacs A, Kelly DP, Saffitz JE, Dorn GW, 2nd, Nichols CG, Semenkovich CF. Fatty acid synthase modulates homeostatic responses to myocardial stress. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30949–30961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betsuyaku T, Nnebe NS, Rune S, Patibandla S, Krueger CM, Yamada KA. Overexpression of cardiac connexin45 increases susceptibility to ventricular tachyarrhythmias in vivo. AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;290:H163–H171. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01308.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin MD, Lu MM, Petrenko NB, Hawkins BJ, Gupta TH, Lang D, Buckley PT, Jochems J, Liu F, Spurney CF, Yuan LJ, Jacobson JT, Brown CB, Huang L, Beermann F, Margulies KB, Madesh M, Eberwine JH, Epstein JA, Patel VV. Melanocyte-like cells in the heart and pulmonary veins contribute to atrial arrhythmia triggers. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:3420–3436. doi: 10.1172/JCI39109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li A, Knutsen RH, Zhang H, Osei-Owusu P, Moreno-Dominguez A, Harter TM, Uchida K, Remedi MS, Dietrich HH, Bernal-Mizrachi C, Blumer KJ, Mecham RP, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Hypotension Due to Kir6.1 Gain-of-Function in Vascular Smooth Muscle. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000365. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huikuri HV, Juhani Junttila M. Clinical aspects of inherited J-wave syndromes. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2015;25:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobrzynski H, Flagg TP, Chandler NJ, Lopatin AN, Nichols CG, Boyett MR. Distribution of GFP-tagged Kir6.2 and Kir2.1 K+ channel subunits in SA and AV nodes from transgenic mice. Journal of Physiology; Proceedings of Bristol meeting; June, 2005.2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koster JC, Permutt MA, Nichols CG. Diabetes and insulin secretion: the ATP-sensitive K+ channel (K ATP) connection. Diabetes. 2005;54:3065–3072. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koster JC, Knopp A, Flagg TP, Markova KP, Sha Q, Enkvetchakul D, Betsuyaku T, Yamada KA, Nichols CG. Tolerance for ATP-insensitive K(ATP) channels in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:1022–1029. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flagg TP, Kurata HT, Coetzee WA, Magnuson MA, Lefer DJ, Nichols CG. Circulation. AHA Scientific Sessions; 2007. Differential make-up of atrial and ventricular KATP: Atrial KATP channels are encoded by SUR1; pp. 647–656. Late Breaking Abstract (Accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichols CG, Lederer WJ. The regulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channel activity in intact and permeabilized rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology London. 1990;423:91–110. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis J, Maillet M, Miano JM, Molkentin JD. Lost in Transgenesis: A User's Guide for Genetically Manipulating the Mouse in Cardiac Research. Circulation Research. 2012;111:761–777. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padrini R, Bova S, Cargnelli G, Piovan D, Ferrari M. Effects of pinacidil on guinea-pig isolated perfused heart with particular reference to the proarrhythmic effect. British journal of pharmacology. 1992;105:715–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawanobori T, Adaniya H, Yukisada H, Hiraoka M. Role for ATP-sensitive K+ channel in the development of A-V block during hypoxia. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 1995;27:647–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haissaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F, Weerasooriya R, Probst V, Loussouarn G, Horlitz M, Liersch R, Schulze-Bahr E, Wilde A, Kaab S, Koster J, Rudy Y, Le Marec H, Schott JJ. Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaney JT, Muhammad R, Blair MA, Kor K, Fish FA, Roden DM, Darbar D. A KCNJ8 mutation associated with early repolarization and atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2012;14:1428–1432. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes: new clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2503–2513. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surah-Narwal S, Xu SZ, McHugh D, McDonald RL, Hough E, Cheong A, Partridge C, Sivaprasadarao A, Beech DJ. Block of human aorta Kir6.1 by the vascular KATP channel inhibitor U37883A. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:667–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.