Abstract

Synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-250 in ‘herbal incense’ also called ‘spice’ were first introduced in many countries. Numerous synthetic cannabinoids with similar chemical structures emerged simultaneously and suddenly. Currently there are not sufficient data on their adverse effects including neurotoxicity. There are only anecdotal reports that suggest their toxicity. In the present study, we evaluated the neurotoxicity of two synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-081 and JWH-210) through observation of various behavioral changes and analysis of histopathological changes using experimental mice with various doses (0.1, 1, 5 mg/kg). In functional observation battery (FOB) test, animals treated with 5 mg/kg of JWH-081 or JWH-210 showed traction and tremor. Their locomotor activities and rotarod retention time were significantly (p<0.05) decreased. However, no significant change was observed in learning or memory function. In histopathological analysis, neural cells of the animals treated with the high dose (5 mg/kg) of JWH-081 or JWH-210 showed distorted nuclei and nucleus membranes in the core shell of nucleus accumbens, suggesting neurotoxicity. Our results suggest that JWH-081 and JWH-210 may be neurotoxic substances through changing neuronal cell damages, especially in the core shell part of nucleus accumbens. To confirm our findings, further studies are needed in the future.

Keywords: Synthetic cannabinoid, Neurotoxicity, Functional observation battery, Motor function, Histopathology

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of 2000s, herbal mixtures with trade names of ‘Spice’, ‘K2’, ‘Yucatan Fire’ have suddenly emerged in many countries, including USA, Japan, Germany, Switzerland, UK, and others [United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (UNODC), 2011, Synthetic cannabinoids in herbal products, Vienna, Austria]. These herbal incenses contain synthetic cannbinoids, representatively JWH-018 and JWH-250. They are expected to have cannabis-like effects as cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) agonists (Piggee, 2009). Synthetic cannabinoids are referred to as substances with structural features that allow binding to one of the known cannabinoid receptors, i.e. CB1 or CB2, present in human cells and compound with similar chemical structures (Fattore, et al., 2001; Auwarter, et al., 2009). The CB1 receptor is located mainly in the brain and spinal cord. It is responsible for the typical physiological effects, particularly the psychotropic effects of cannabis. However, the CB2 receptor is located mainly in the spleen and cells of the immune system. It may mediate immune-modulatory effects (Compton, et al., 1993; Porter and Felder, 2001).

Some well-known synthetic cannabinoids such as JWH-018 have been studied relatively well by many researchers. Most of them are under control by legislation in many countries. In order to meet the needs of users who are willing to seek for substitutions, numerous new synthetic cannabinoids with similar chemical structures to that of ‘conventional’ ones appeared. These new synthetic cannabinoids are problematic due to the lack of information on their risks including toxicity, dependence liability, and appropriate doses. One can only recognize their risks only through some anecdotal reports.

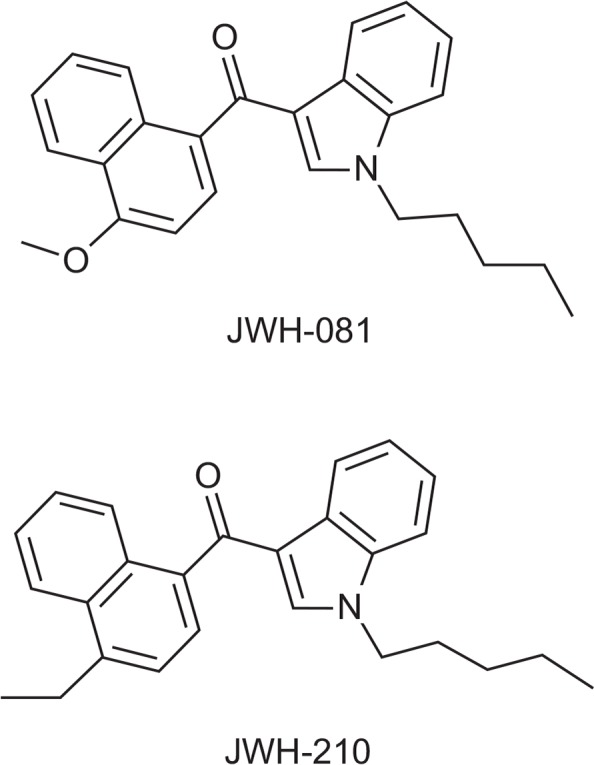

JWH-081 and JWH-210 are classified into the aminoalkylindole group [Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drug (ACMD), 2009, Consideration of the Major cannabinoid agonists, Home Office, London, UK] with naphthoylindole moiety as a parent structure. Their psychological dependence liabilities have been reported in our previous study (Cha et al., 2014). However, there are only a couple of anecdotal reports suspecting the possibility of their neurotoxicity with no scientific evidence (Cohen et al., 2012; McGuinness and Newell, 2012; Harris and Brown, 2013; Hermanns et al., 2013). Generally, neurotoxicity of a substance is evaluated by animal behavioral aspects, i.e. functional observation battery (FOB) tests (O’Callaghan et al., 2014). However, because of their subjective properties, it is necessary to set up a more objective automated measurement to determine their neurotoxicity. In the present study, we performed various methods based on animal behavioral testing including FOB test for general behavioral observation, rotarod test, locomotor activity test for motor function evaluation, and water-maze test for learning/memory evaluation. We also examined their neurotoxicity using brain samples through histopathological diagnose, especially in the nucleus accumbens core region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and substances

ICR mice (weight, 20–22 g) obtained from Samtacobio Korea (Osan, Korea) were housed in adequate size of groups in a temperature-controlled 22 ± 2°C room with a 12 hour light/dark cycle (lights on 07:00 to 19:00, 150–300 Lux). The animal tests were approved by NIFDS/MFDS Animal Ethics Board (1301MFDS009). The animals received solid diet and tap water ad libitum. Animal husbandry conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NRC 1996). We performed all experiments between 09:00 and 18:00. Cannabinoids JWH-081 and JWH-210 (Fig. 1) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of JWH-081 and JWH-210.

Methods

Functional Observation Battery (FOB) test:

The FOB test was performed using published procedures (Moser et al., 1989) with some modifications. Briefly, the FOB test was comprised of several behavioral changes including catalepsy, traction, tremor, convulsion, exopthalmos, piloerection, salivation, lacrimation, diarrhea, skin coloration, pinna reflex, righting reflex, and death. One group of mice was administered with negative control (vehicle, DMSO:saline:tween80=1:18:1, 1 mg/kg, intraperitoneally [i.p.]), positive control (methamphetamine, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) or one of the three doses of test substances (0.1, 1, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) once every other day for 10 days. Two different observers checked each items described above simultaneously to prevent arbitrariness. The observational check lists and measurements are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Check list for functional observational battery test

| Observation list | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Catalepsy | Numbers of mice that maintain their position of hanging with forelimbs for 10 sec above on a metal rod of 2 mm diameter |

| Traction | Numbers of mice that fall from a metal rod of 2 mm diameter without resistance when pulled their tails |

| Tremor | Numbers of mice that show tremor |

| Convulsion | Numbers of mice that show convulsion |

| Exopthalmos | Numbers of mice that bulge out their eyeballs |

| Piloerection | Numbers of mice whose hair errect |

| Salivation | Numbers of mice that salivate |

| Lacrimation | Numbers of mice that shed tears |

| Diarrhea | Numbers of mice that suffer from diarrhea |

| Skin Coloration | Numbers of mice whose skin (ear) colors are changed |

| Pinna reflex | Numbers of mice that move pinna when touched by other objects (such as pig hair) |

| Righting reflex | Numbers of mice that don’t upside down when positioned dorsally |

| Death | Numbers of died mice |

Motor function test:

The motor function changes were evaluated through two test methods: locomotor activity and rota-rod test. In both tests, a group of mice were treated with negative control (vehicle, 1 mg/kg, i.p.), positive control (methamphetamine, 1 mg/kg, i.p.), or one of the three doses of test substances (0.1, 1, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) once every other day for 10 days. The test apparatus for the locomotor activity test was designed to measure locomotor activity automatically using UV system (AM 1051, Benwick Electronics, Benwick, UK) when experimental animals moved in the chamber. The locomotor activity of the mice was measured 30 min and 2 hrs after the last substance administration. To evaluate whether the changes of coordinative functions by CNS damages were due to test substances, rota-rod test was performed using Rota-rod apparatus (Daejong, Seoul, Korea). Mice that remained their position on the running apparatus at 10 rpm for at least 2 min were selected for further evaluation. It was considered as coordination disturbance when mice fell from the test apparatus within 2 min.

Learning and memory test:

Morris water maze test was performed to evaluate the changes of learning and memory function through administration of the test substances. Two sets of experiment were performed. In test 1, the substances including vehicle and methamphetamine were injected through i.p. route once every other day for 10 days. After the last administration, the first trial was performed. The same procedure was then applied to the mice once every day for 5 days. Test 2 was performed everyday for 5 days after consecutive administration of the substances, including negative (vehicle) and positive (methamphetamine) controls. The apparatus for the Morris water maze test consisted of four sections: north-east (NE), south-east (SE), south-west (SW), north-west (NW). A platform (20 cm height, 10 cm diameter) was placed at NW section. The temperature of water was 24 ± 2°C and the level of water was 1.5 cm higher than the height of the platform. The movement of experimental mice was measured using Smart version 2.5.21 program provided from Panlab Harvard apparatus (MA, USA). Memory acquisition and memory retention was evaluated separately. Memory acquisition was measured through escape latency. Memory retention was measured after the memory acquisition was tested as a probe trial.

Histopathology analysis:

Brain samples were prepared from the mice after the last administration of test substances. Nucleus accumbes (NAc) and hippocampus regions were collected in particular because they are known to be associated with dopaminergic pathways and learning/memory functions. Brain samples were dissected after fixation with 10% formalin and embedding with paraffin using a microtome (Leica, Germany). The sliced samples were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and observed with a bright field microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis:

All data were presented as means ± SEM. Western blot data were analyzed by Student’s t-test. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Functional observational battery test

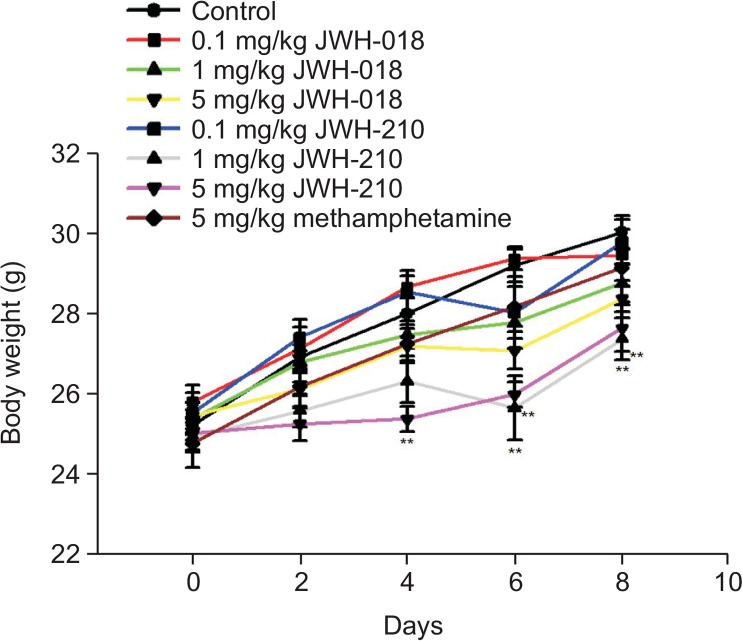

All tested groups consisted of 12 mice each. Some mice showed abnormal behaviors (catalepsy, loss of traction, convulsion) right after the administration of the tested substances. Most of the abnormalities were normalized in synthetic cannabinoid treated mice although those abnormal behaviors remained in methamphetamine treated animals after 2 hr of administration. After the first injection, 6 mice of the positive control group (methamphetamine, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) showed loss of traction, of which 4 showed tremor. A total of 5 mice in the JWH-081 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) treated group and 6 mice in the JWH-210 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) treated group showed loss of traction, of which 4 and 5 showed tremor, respectively. One mouse treated with 0.1 mg/kg of JWH-210 died. However, the death seemed to due to causes other than the effect of the substance (Table 2). All groups treated with tested synthetic cannabinoids showed decreased weight gain rate in a dose-dependent manner. Particularly, the 1 and 5 mg/kg JWH-210 treated groups showed statistically significant decreases (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Functional observational battery test result

| Observation item | 1st injection | 2nd injection | 3rd injection | 4th injection | 5th injection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Con. | Met. | JWH-081 | JWH-210 | Con. | Met. | JWH-081 | JWH-210 | Con. | Met. | JWH-081 | JWH-210 | Con. | Met. | JWH-081 | JWH-210 | Con. | Met. | JWH-081 | JWH-210 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||

| Catalepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Traction | 0 | 6 | 2 | 4/1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6/1 | 0 | 5/1 | 0 | 2 | 4/1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tremor | 0 | 4/2 | 0 | 1 | 4/2 | 0 | 1 | 5/2 | 0 | 2/1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3/2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/1 |

| Convulsion | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Exopthalmos | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Piloerection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salivation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lacrimination | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin coloration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pinna reflex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Righting reflex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3.

Changes of body weight

| 1st injection | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 25.2 ± 0.4 | 26.9 ± 0.3 | 28.0 ± 0.4 | 29.2 ± 0.4 | 30.0 ± 0.4 | |

| JWH-081 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 25.8 ± 0.4 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 28.6 ± 0.3 | 29.3 ± 0.3 | 29.4 ± 0.6 |

| 1 | 25.3 ± 0.4 | 26.8 ± 0.3 | 27.5 ± 0.3 | 27.8 ± 0.4 | 28.7 ± 0.5 | |

| 5 | 25.5 ± 0.3 | 26.1 ± 0.2 | 27.2 ± 0.3 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 28.3 ± 0.3 | |

| JWH-210 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 25.5 ± 0.5 | 27.4 ± 0.4 | 28.5 ± 0.5 | 28.0 ± 0.9 | 29.8 ± 0.6 |

| 1 | 24.9 ± 0.4 | 25.6 ± 0.4 | 26.3 ± 0.5 | 25.7 ± 0.8** | 27.4 ± 0.5** | |

| 5 | 25.0 ± 0.4 | 25.3 ± 0.3 | 25.4 ± 0.3** | 26.0 ± 0.3** | 27.6 ± 0.6** | |

| METH (5 mg/kg) | 24.8 ± 0.6 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 27.2 ± 0.5 | 28.2 ± 0.5 | 29.1 ± 0.5 |

Each value represents the mean ± SEM (**p<0.01, compared to control).

Fig. 2.

Change of body weight following the treatments with JWH-081 and JWH-210 in mice. Body weight was measured before every drug administration (n=12). **p<0.01, compared to control.

Motor function test

In locomotor activity, methamphetamine treated group showed approximately 4.2 times increase compared to the negative control treated group. On the other hand, JWH-081 (1, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) and JWH-210 (1, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) treated group showed significant decrease. Such decrease remained 2 hr after the administration (Table 4). The coordinative function changes were evaluated through rota-rod test. A total of 2 and 3 methamphetamine treated mice fell from the spinning rod 30 min and 2 hr after the administration, respectively. In addition, 2 to 5 mice treated with JWH-081 and JWH-210 fell from the rotating rod (Table 4).

Table 4.

Changes of motor activity (locomotor activity)

| Activity (% of control) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 30 min after injection | 2 hr after injection | ||

| Control | 100.0 ± 11.3 | 100.0 ± 5.9 | |

| JWH-081 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 79.1 ± 11.4 | 85.0 ± 6.8 |

| 1 | 62.2 ± 9.0* | 67.8 ± 7.7** | |

| 5 | 58.8 ± 5.8** | 67.0 ± 7.2** | |

| JWH-210 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 78.9 ± 8.5 | 87.3 ± 6.4 |

| 1 | 60.8 ± 7.2* | 103.2 ± 16.2 | |

| 5 | 44.7 ± 10.1** | 76.1 ± 10.6 | |

| METH (5 mg/kg) | 422.8 ± 28.7** | 130.8 ± 16.1 | |

Mice were subjected to the tests 30 min and 2 h after the last injection (5th) of JWH. Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n=12).

p<0.05,

p<0.01, compared to control (student’s t-test).

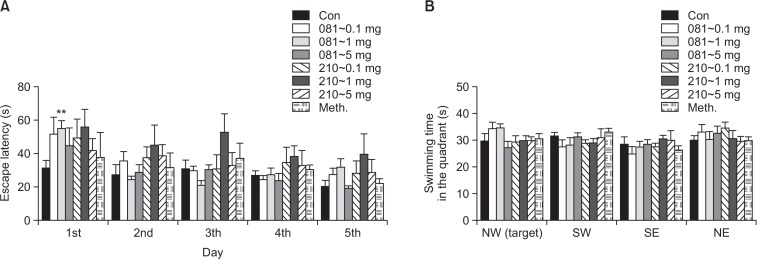

Learning and memory test

In order to evaluate changes of learning and memory functions, Morris water maze test was performed in two aspects: acquisition and retention. No change was observed in either test (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of of JWH-081 and JWH-210 on MWM performance of mice. (A) Mean latency to find a hidden platform during 5 consecutive days training (memory acquisition); (B) The time spent in each quadrant within 120 s, which was measured 24 h after the last trials without the platform once placed in the NW quadrant. Drug was administered 5 times every other day, and the first trial was performed 2 h after the last administration. Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n=6). **p<0.01, compared to control.

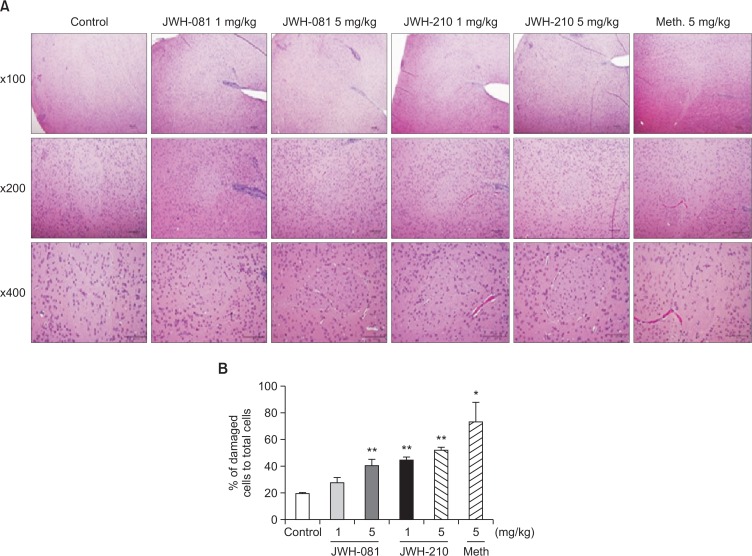

Histopathology analysis

After administering test substances once every other day for 10 days, brain samples of mice were collected, especially at nucleus accumbens and hippocampus regions. They were stained using hematoxylin and eosin. In samples treated with methamphetamine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and high dose of tested synthetic cannabinoids (5 mg/kg i.p.), decrease in neural cell number at the core part of nucleus accumbens, pyknotic nucleus at the core and shell part of nucleus accumbens, and distortion of cell membrane were observed (Table 5, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Table 5.

Changes of motor activity (rotarod test)

| Number of mice which fell down in 2 min | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| 30 min after injection | 2 hr after injection | ||

| Control | 1 | 1 | |

| JWH-081 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| JWH-210 (mg/kg) | 0.1 | 4 | 3 |

| 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | |

| METH (5 mg/kg) | 2 | 3 | |

Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n=12).

p<0.05,

p<0.01, compared to control (student’s t-test).

Fig. 4.

Effects of JWH-081, JWH-210, and methamphetamine in nucleus accumbens. (A) Representative photomicrographs of the nucleus accumbens were shown. Brain sections taken after 5 times injection of every other day were stained with H&E and observed using a bright-field microscope. Pyknotic nucleus and low hematoxilin affinity were observed in methamphetamine and high dosage of JWH treated groups. (B) The ratio of damaged cells containing pyknotic or condensed nuclei and low hematoxilin affinity to total cells were calculated in nucleus accumbens. Each value represents the mean ± SEM (n=3). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, compared to control.

DISCUSSION

Synthetic cannabinoids have been emerged suddenly due to the need of those who expect cannabis-like effects by using these substances. Based on their parental chemical structures, the most problematic chemical structures of synthetic cannabinoids are aminoalkylindoles consisting of four subclasses: naphthoylindoles, phenylacetylindoles, naphthylme-thylindoles, and benzoylindoles (ACMD). One of the reasons that aminoalkylindoles have caused a lot of social problems is that they are structurally diversified. The substances used in the present study both possess naphthoylindole moiety as their parental structure. The difference between the two substances is that JWH-081 has a methoxy group on the naphthalene moiety whereas JWH-210 has an ethyl group at the same position.

One of the biggest problems due to the structural diversity of aminoalkylindole group is the lack of information about their harms on human body, including dependence potential and toxic effects on various organs. In case of cannabis or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, there are many previous studies regarding with their dependence potential and neurotoxicity (Cororan, et al., 1974; Harris, et al., 1974; Leite and Culini, 1974; Hutcheson, et al., 1998). There are a few previous reports on the dependence potential of particular synthetic cannabinoids known well such as HU-210, JWH-018, JWH-250, CP-47,497, and so forth (Chaperon et al., 1998; Cheer et al., 2000; Martellota, et al. 1998; Vlachou et al., 2005; Wiley et al., 2011). However, slight structural changes might cause biochemical properties including dependence liability and neurotoxicity. In addition, the lack of information about neurotoxicity of synthetic cannabinoids could allow abusers consume those substances undiscerningly. Only a few case reports about the dangers of some synthetic cannabinoids due to neurotoxicity have been published (Cohen et al., 2012; McGuinness et al., 2012; Harris and Brown, 2013; Hermanns et al., 2013).

In the present study, we investigated the possibilities of neurotoxicity of two synthetic cannabinoids JWH-081 and JWH-210 using behavioral pharmacological approaches. Functional observation battery (FOB) test was used to evaluate the general behavioral changes in this study. Locomotor activity and rota-rod test were used to observe motor coordinative function. Morris water maze test was performed to evaluate the changes in learning and memory function. FOB is a behavioral screening procedure commonly used in safety pharmacology and toxicology studies to assess the potentially adverse effects of test agents on the central nervous system (Boucard et al., 2010). In this study, histopathological evaluation was performed to confirm the possibility of neurotoxicity of the tested substances by hematoxylin and eosin staining method from collected brain samples. In FOB test, animals treated with 5 mg/kg of JWH-081 or JWH-210 showed traction and tremor. Their locomotor activities and rotarod retention time were significantly (p<0.05) decreased. However, no significant change was observed in learning or memory function. In histopathological analysis, neural cells of the animals treated with the high dose (5 mg/kg) of JWH-081 or JWH-210 showed distorted nuclei and nucleus membranes in the core shell of nucleus accumbens, suggesting neurotoxicity. Our results suggest that JWH-081 and JWH-210 may be neurotoxic substances through changing neuronal cell damages, especially in the core shell part of nucleus accumbens. To confirm our findings, further studies are needed in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (13181MFDS654) of the National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation, Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- Auwarter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Muller M, Putz M, Rerreiros N. ‘Spice’ and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? J Mass Spectrom. 2009;44:832–837. doi: 10.1002/jms.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucard A, Betat AM, Forster R, Simonard A, Forger G. Evaluation of neurotoxicity potential in rats: the functional observational battery. In: Enna SJ, Williams M, editors. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New Jersey: 2010. Ch 10, Unit 10, 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha HJ, Lee KW, Song MJ, Hyeon YJ, Jang CG, Ahn JI, Jeon SH, Kim HU, Kim YH, Seong WK, Kang H, Yoo HS, Jeong HS. Dependence potential of the synthetic cannabinoids JWH-073, JWH-081, and JWH-210: in vivo and in vitro approaches. Biomol Ther. 2014;22:363–369. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaperon F, Soubrie P, Puech AJ, Thiebot MH. Involvement of central cannabinoid (CB) receptors in the establishment of place conditioning in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;135:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s002130050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer JF, Kendall DA, Marsden CA. Cannabinoid receptors and reward in the rat: a conditioned place preference study. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Morrison S, Greenberg J, Saidinejad M. Clinical presentation of intoxication due to synthetic cannabinoids. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1064–1067. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DR, Rice KC, De Costa BR, Razdan RK, Melvin LS, Johnson MR, Martin BR. Cannabinoid structure-activity relationships: correlation of receptor binding and in vivo activities. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran ME, Amit Z. Reluctance of rats to drink hashish suspensions: free-choice and forced consumption, and the effects of hypothalamic stimulation. Psychopharmacologia. 1974;35:129–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00429580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Cossu G, Martellotta CM, Fratta W. Intravenous self-administration of the cannabinoids CB receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:410–416. doi: 10.1007/s002130100734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris CR, Brown A. Synthetic cannabinoid intoxication: a case series and review. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RT, Waters W, McLendon D. Evaluation of reinforcing capability of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1974;37:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00426679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns-Clausen M, Kneisel Cl, Szabo B, Auwarter V. Acute toxicity due to the confirmed consumption of synthetic can-nabinoids: clinical and laboratory findings. Addiction. 2013;108:534–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson D, Tzavara ETh, Smadja C, Vlijent E, Roques B, Hanoune J, Maldonado R. Behavioral and biochemical evidence for signs of abstinence in mice chronically treated with Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1567–1577. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite JR, Culini EA. Failure to obtain cannabis-directed behavior and abstinence syndrome in rats chronically treated with Cannabis sativa extracts. Psychopharmacology. 1974;36:133–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00421785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martellota MC, Cossu G, Fattore L, Gessa GL, Fratta W. Self-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55-212,2 in drug-naïve mice. Neuroscience. 1998;85:327–330. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness TM, Newell D. Risky recreation: synthetic cannabinoids have dangerous effects. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2012;50:16–18. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20120703-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC. Screening approaches to neurotoxicity: a functional observational battery. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1989;8:85–94. doi: 10.3109/10915818909009095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan JP, Daughtrey WC, Clark CR, Schreiner CA, White R. Health assessment of gasoline and fuel oxygenate vapors: neurotoxicity evaluation. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;70:S35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggee C. Investigating a not-so-natural high. Anal Chem. 2009;81:3205–3207. doi: 10.1021/ac900564u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter AC, Felder CC. The endocannabinoid nervous system: unique opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90:45–60. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou S, Nomikos GG, Panagis G. CB cannabinoid receptor agonists increase intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:498–508. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Martin BR, Huffman JW. 1-Pentyl-3-phenylacetylindoles and JWH-018 share in vivo cannabinoid profiles in mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;123:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]