Abstract

Background: Over the past 15 years, the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services, currently described as integrative medicine (IM) when used together with conventional medicine , has continued to rise in the United States. The trends seen in the civilian population are mirrored within the U.S. Military.

Objective: A survey was conducted to show the change in the prevalence of integrative medicine services, budgeting of those services, and ongoing research in IM within Department of Defense (DoD) medical treatment facilities (MTFs) from 2005 through 2009.

Materials and Methods: Design: The Deputy Chief of Clinical Services or Service equivalent was contacted at fourteen selected DoD MTFs. Comprehensive structured telephone interviews were conducted using a formatted 20-item questionnaire. The questionnaire design was of a mixed model with open and closed formats as well as dichotomous yes/no questions. The questions covered the subject areas of available services, budgeting, and research. The initial survey was conducted in 2005 with a follow-up survey conducted in 2009. Setting: This survey involved DoD MTFs. Main Outcome Measures: The surveys were conducted to determine the prevalence of IM services within selected DoD facilities.

Results: There was a steady increase in the number of IM services available in the DoD MTFs from 2005 through 2009. Acupuncture, biofeedback, nutritional counseling, and spiritual healing were the most prevalent IM services in 2009. Funding sources changed from central funding (Offices of the Surgeon General) to Congressional and local funding.

Conclusions: It is essential that the DoD medical community provides safe and effective treatments by providing oversight of IM services, collaboration for research, credentialing of practitioners, and establishing educational programs.

Key Words: : Complementary Therapies/Utilization, Alternative Medicine, Integrative Medicine, Prevalence, Utilization, Department Of Defense, Questionnaires, Comparative Study, Military Personnel/Statistics and Numerical Data

Introduction

Health care has continued to evolve, change, and grow over the past several decades. Some of these changes have been patient-driven. People are turning to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for treatment because the current biomedical model of care is not meeting their needs. The prevalence of CAM use has increased since it was first studied in the early 1990s. In studies by Eisenberg et al. and Tindle et al., usage of CAM services among the general U.S. population has increased from 33.8% in 1990 to 42.1% in 1997,1 and to 62% in 2002.2 Barnes et al. of the National Health Interview Survey reported similar findings with an average increased prevalence of 31% during the 8-year period studied (28.9% increased to 38% from 1999 until 2007).3 Eisenberg et al. also reported that the number of visits to nonconventional providers in the United States has exceeded the number of visits to all primary care providers. Furthermore, Americans are willing to pay more out-of-pocket for CAM treatments than for out-of-pocket hospitalizations.4

The trends in the U.S. Military mirror those reported in civilian medical settings. A study at the Madigan Army Medical Center showed that 81% of active duty soldiers, retirees, and family members used one or more CAM services, with 69% requesting such services be offered at the Military treatment facility (MTF).5 Furthermore, a study of U.S. Navy and Marine Corp personnel showed that 37% of the personnel have used one or more CAM services. Herbal therapies were the most common type of CAM use reported.6

The Veterans Affairs (VA) system is similar to that of the Department of Defense (DoD). The Department of VA Technical Advisory Group (TAG) in collaboration with the Healthcare Analysis & Information Group (HAIG) surveyed all of the VA facilities in 1998 and 2011. The HAIG study showed that 88% (125/141) of the VA facilities used CAM services either on-site or by referral. The final conclusions of the HAIG study questioned the direction and the goals of medical care, including CAM provider qualifications, evidence-based research, and oversight. These observations were noted in 2011, and there was guidance on documentation, privileging, credentialing, and Veterans' interest and utilization of CAM services.7,8

There are numerous studies wherein researchers have evaluated usage of CAM among Military beneficiaries and their perspectives on CAM versus conventional medicine.9–14 One such study performed at the Southern Arizona VA Health Care system, showed that the use of CAM was not necessarily associated with conventional care overall but rather involved a few very specific areas where conventional medicine posed problems. These included prescription side-effects, lack of preventive medicine, a desire for emphasis on nutrition and exercise, and a desire to have more holistic health care plans.15

Commercial bombardment of promises of euphoric lives, better and more trim bodies, and pain-free living fuels the demand for CAM. Although there has been an increasing body of research, there is much to be learned regarding CAM's safety and efficacy. The National Center on Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH; formerly the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine) defined CAM as group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine. IM refers to the practice that combines both conventional and CAM treatments for which there is evidence of safety and effectiveness.16 Recently, the NCCAM changed its name to the NCCIH to reflect the evolution in medicine better.

This increasing trend in usage and the willingness to pay out-of-pocket for CAM has prompted the medical community to react. It is incumbent upon us as a medical community to guide patients to make intelligent decisions about their health and medical care. If we do not engage with patients and provide them with some oversight, they have shown that they will seek out alternative treatments without our input.

Often, the U.S. Military health care system has been on the forefront of medical advancements, such as air evacuation, trauma care, hemostasis and hemorrhage control, and prosthetics technology. Often, this has been the result of an urgency to meet the needs of our battle-injured Military personnel. The Military is taking a lead in IM as well. In 2009, The Army Surgeon General chartered the Pain Management Task Force to review the current status of pain management within the Department of the Army. In 2010, the Task Force published its report with the recommendation for a comprehensive pain-management strategy focused on an interdisciplinary, holistic, multimodal, patient-centered approach.17 As a result of this initiative, The Office of the Surgeon General (OTSG) of the Army was recognized by the American Academy of Pain Medicine for the OTSG's efforts to take a holistic approach to pain management; efforts that included improved anesthesia at the point of injury to nonpharmacologic approaches, such as mindfulness, acupuncture, and biofeedback.

Therefore, to serve the medical community best, baseline information about available services, usage patterns, belief systems, and perceptions about CAM needs to be obtained. A survey was conducted to identify available CAM services within fourteen selected MTFs within the DoD and to evaluate the changes over time from 2005 to 2009. The studies from 2005 and 2009, when combined can serve to understand better the broader context of CAM usage within the DoD and establish a baseline for further studies regarding usage, feasibility, accessibility, acceptability, and sustainability for CAM policy development as well as the new paradigm of holistic approaches to medical management.

Materials and Methods

The Deputy Chief of Clinical Services (DCCS) or Service equivalent was contacted at fourteen selected DoD MTFs. In 2009, only thirteen facilities responded. Thus, the N is 14 in 2005 and 13 in 2009. The medical centers for each service were selected. These MTFs represent the DoD equivalent of civilian academic hospitals. Within the DoD, there are 8 Army, 3 Naval, and 2 Air Force medical centers. The Great Lakes Naval Health Clinic was also surveyed. These sites were selected as a representative of each service because of their medical center status. Comprehensive structured telephone interviews were conducted, using a formatted 20-item questionnaire. The questionnaire design was of a mixed model with an open and closed format as well as dichotomous yes/no questions. The questions covered available services, budgeting, and research. The initial survey was conducted in 2005 with a follow-up survey conducted in 2009.

Main Outcome Measure

The surveys were conducted to determine the prevalence of IM services within the fourteen selected DoD facilities.

Results

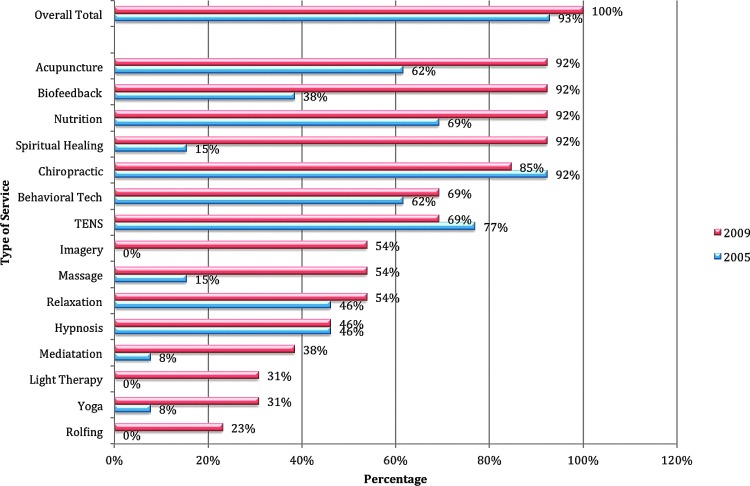

The 2005 initial study showed that 93% (N = 14) of the surveyed facilities offered IM services with 43% offering six or more modalities. This increased to 100% (N = 13) in 2009 with 92% offering six of more modalities. One site offered nineteen IM services in 2009, representing an increase in services of 171%, compared to 2005. However, the greatest increase in the number of services available was 333%, with three available services in 2005 compared to 13 in 2009. The top four IM services were (1) acupuncture, (2) biofeedback, (3) nutritional counseling, and (4) spiritual healing in 2009, compared to chiropractic, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, nutritional counseling, and meditative behavioral techniques in 2005 (Fig. 1). There was no single modality that was available at all facilities. The modalities with the greatest increase in availability from 2005 to 2009 were spiritual healing (500%), meditation (400%), yoga (300%), and massage therapy (250%). In 2009, 75% of the sites added at least one new IM modality, with imagery added at seven sites and light therapy at four sites. Two sites decreased the number of available modalities.

FIG. 1.

Change in integrative medicine service types available at selected U.S. Department of Defense facilities from 2005 to 2009. TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Only one facility had a dedicated Center for Integrative Medicine in 2005 and 2009. All remaining facilities offered IM services with other conventional practices such as family practice, physical medicine and rehabilitation, pain management, or internal medicine.

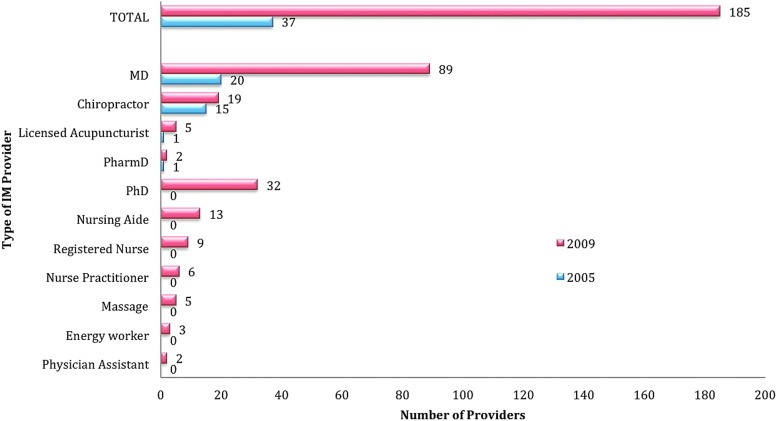

There was a 400% increase in the number of individual providers offering IM services during the study period (37 in 2005 and 185 in 2009; Fig. 2)

FIG. 2.

Changes in integrative medicine provider types at selected U.S. Department of Defense facilities from 2005 to 2009.

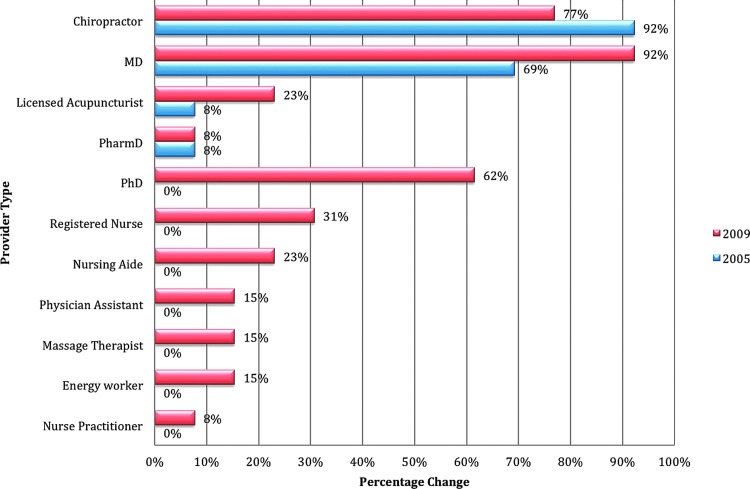

The most common provider types were medical doctors (MDs) in both 2005 and 2009. The provider types that had the largest increase were MDs (69), PhDs (32), and nurses' aides (13). Seven additional provider types offered services from 2005 to 2009. This included PhDs, nurses' aides, RNs, nurse–practitioners, massage therapists, energy workers, and physician assistants (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Changes in medical provider types at selected U.S. Department of Defense facilities from 2005 to 2009.

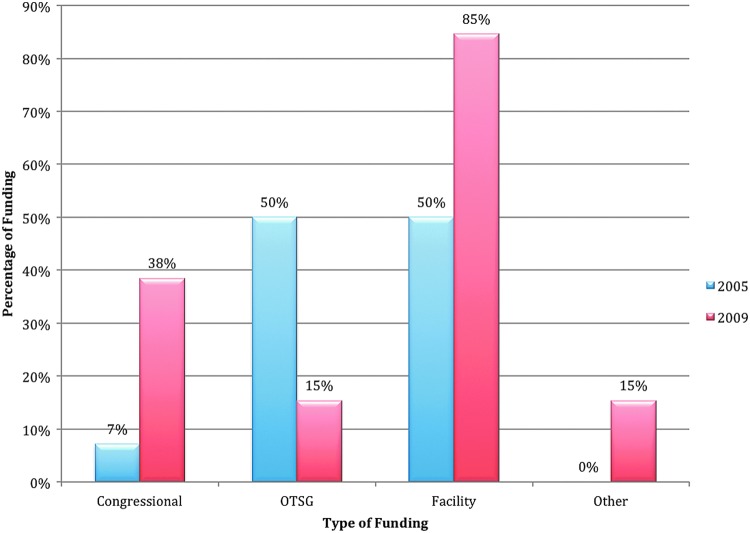

Funding sources for provision of IM services changed during the study period. In 2005, there was an equal contributions (50%) of funding from The Department of Army (DA) OTSG and local facility budgets, with 7% received from Congressional sources. In 2009, Congressional and local facilities' sources of funding increased by 438% and 69%, respectively, with a decrease in DA OTSG funding by nearly 70% (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Changes in integrative medicine funding sources at selected U.S. Department of Defense facilities from 2005 to 2009. OTSG, Office of the Surgeon General (of the Army).

The number of facilities actively researching IM practices doubled from three to six during the study period.

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that up to 42% of the U.S. population is using CAM. In contrast, at a single Military MTF, 81% of Military beneficiaries were using CAM).1,5 The Department of VA in collaboration with the HAIG showed 88% of the VA facilities use IM services, either on-site or by referral.7 The current surveys showed surprising results, with 93% of the fourteen surveyed DOD facilities offering IM services. In the more recent survey, the most common services offered were acupuncture, biofeedback, nutritional counseling, and spiritual healing.

The design of this study was two formatted telephonic surveys of each DCCS or Service equivalent on the available IM services within each facility. The limitation of this method is that the DCCS' or Service equivalents could not validate their assessments of their facilities' utilization by communicating through simple telephonic queries. A better method of study would have been to have the DCCS' query their facilities to verify the information for the study and submit their facilities' results. In 2009 there were 11 distinct provider types providing IM services. This can lead to challenging situations. As an example, several provider types can perform acupuncture treatments; however, not all of these providers have the same level of credentialing and privileging.

The Department of the Defense Services (Navy, Air Force, and Army) and the VA are developing such standards for acupuncture and other IM provider types and modalities. Importantly, consensus between the DoD Services and the VA needs to be obtained to ensure consistency and standardization across similar government agencies. This will assist in policy development, which is acceptable to all stakeholders. In addition, given that few locations are engaged in IM research, there needs to be more emphasis on, and funding for, more research in IM. A central clearinghouse or agency can provide oversight to prevent duplication of research efforts, encourage multisite endeavors, and target the specific needs of the Military population.

A recent DoD study showed that the Military population is actively using supplements to increase their physical performance and well-being.18 Therefore, it is of great importance that there is a consistent and a collaborative research effort with respect to IM services, particularly those used by active duty personnel, because the use of IM can be and is often patient-driven. Patients will use IM even when they have to pay out-of-pocket costs. Therefore, these patients may not choose safe options but rather opt for the latest trends and fads that circulate in gyms and on television commercials. This emphases the importance of IM research to identify safe and effective treatments.

These current surveys, like the HAIG survey, raise questions regarding the direction and goal of Military medicine with respect to IM. There needs to be oversight of provided and proposed services; privileging of practitioners; fiscal accountability; standardization of treatment and research protocols; productivity and outcome measures; and education of patients, practitioners, and the overall community. In January 2014, the U.S. Defense Health Agency published the “Integrative Medicine Health in the Military Health System Report to Congress.”19 This report showed that 120 (29% of 421) MTFs offered 275 CAM programs. Furthermore, it showed that, during the calendar year 2012, active duty Military members had 213,515 CAM patient visits. The most frequent visits were for chiropractic care (73%) and acupuncture treatments (11%). The most common CAM programs were acupuncture, clinical nutrition, and chiropractic care. The overall recommendations of the report were: (1) The Military medical health system should evaluate CAM programs for safety and effectiveness as well as for cost-effectiveness; (2) the Military medical health system should consider widespread implementation of cost-effective CAM programs that meet guidelines for safety and effectiveness.19

Other areas of study are specific usage of IM by Military beneficiaries and the behaviors and perspectives regarding IM services by Military beneficiaries and by the leadership. In addition, these types of studies should be repeated at regular intervals to track IM services and identify developing trends.

Conclusions

These two surveys from 2005 and 2009 established an initial baseline of CAM services within fourteen selected DoD MTFs. From 2005 through 2009, there was a steady increase in the number of IM services available in the fourteen selected DoD medical treatment facilities. In the 2009 survey, 100% of the fourteen facilities offered IM services, with 92% offering six or more modalities. Nearly all facilities offered such services together with other conventional practices, such as family practice, physical medicine and rehabilitation, pain management, or internal medicine. One facility had a dedicated Center for Integrative Medicine. Six facilities were researching IM practices actively. There is no central proponent for IM services within the DoD, thus, suggesting the need for a leadership position. It is essential that the medical community ensure safe and effective treatments by providing oversight of IM services, collaboration of research, credentialing of practitioners, and establishment of educational programs. A follow-up survey of all the DoD MTFs is currently ongoing.

Recommendations

This study suggests the need for a routine comprehensive survey of participating North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) participating countries. This survey could be performed individually or as part of a collaborative effort. The results will assist in the identification of trends, best practices, perspectives, and potential further endeavors in the integration of IM into NATO Military health care systems. In addition, a NATO-based study would open the potential for cross-NATO collaborative research, clinical practices, and educational opportunities. Finally, the use of IM services by Military individuals must be investigated.

Author Disclosure Statement

COL Richard Petri, MC (MD), is an Active Duty Service Member in the United States Army and was appointed to the NATO panel HFM-195 (“Integrative Medicine Interventions for Military Personnel”) as a technical team member. He was selected to the Chair of the panel in September 2013. Resources from the United States Army supported the travel expenses to the first four team meetings. The fifth meeting lodging expenses were partially supported by a grant from the Geneva Foundation. The remaining expenses were paid through personal resources. No competing financial conflicts exist. Roxana E. Delgado, PhD, MS, is a health scientist at Samueli Institute, a health and wellness research non-profit organization. Resources from Samueli Institute were used to support the author's time and effort to write this chapter. No competing financial conflicts exist.

References

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US Adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11(1):42–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;(343):1–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States: Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherson F, Schwenka MA. Use of complementary and alternative therapies among active duty soldiers, military retirees, and family members at a military hospital. Mil Med. 2004;169(5):354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US Navy and Marine Corps personnel. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klemm Analysis Group (1999). Alternative medicine therapy: Assessment of current VHA practices and opportunities. Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning, Healthcare Analysis & Information Group. Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011. Online document at: www.research.va.gov/research_topics/2011cam_finalreport.pdf Accessed April24, 2015

- 9.George S, Jackson JL, Passamonti M. Complementary and alternative medicine in a military primary care clinic: A 5-year cohort study. Mil Med. 2011;176(6):685–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goertz CM, Long CR, Hondras MA, et al. Adding chiropractic manipulative therapy to standard medical care for patients with acute low back pain: Results of a pragmatic randomized comparative effective study. Spine. 2013;38(8):627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goertz CM, Niemtzow R, Burns SM, Fritts MF, Crawford CC, Jonas WB. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of acute pain syndromes: A pilot study. Mil Med. 2006;171(10):1010–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brookes AJ, Bell IR. A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: Implications for integrated care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1697–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kent JB, Oh RC. Complementary and alternative medicine use among military family medicine patients in Hawaii. Mil Med. 2010;175(7):534–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White MR, Jacobson IG, Smith B, et al. Health care utilization among complementary and alternative medicine users in a large military cohort. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroesen K, Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR. US military Veterans' perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of complementary and alternative medicine. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What's in a Name? Online document at: nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam Accessed May7, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office of the Army Surgeon General, Pain Management Task Force. Final Report: May 2010. Providing a Standardized DoD and VHA Vision and Approach to Pain Management to Optimize the Care for Warriors and Their Families. Online document at: www.regenesisbio.com/pdfs/journal/Pain_Management_Task_Force_Report.pdf Accessed May7, 2014

- 18.RTI (Research Triangle Institute) International. 2008: Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel. A Component of the Defense Lifestyle Assessment Program (DLAP). Washington, DC: RTI; 2008. Online document at: www.tricare.mil/tma/2008HealthBehaviors.pdf Accessed May7, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Defense Health Agency (DHA). Integrative Medicine in the Military Health System Report to Congress. Washington, DC: DHA; 2014. Online document at: tricare.mil/tma/congressionalinformation/downloads/Military%20Integrative%20Medicine.pdf Accessed September9, 2014 [Google Scholar]