Abstract

Background

Ongoing self-management improves outcomes for those with type 2 diabetes (T2D); however, there are many barriers to patients receiving assistance in this from the healthcare system and peers. Findings from our pilot study showed that a virtual diabetes community on the Internet with real-time interaction among peers with T2D—and with healthcare professionals—is feasible and has the potential to influence clinical and psychosocial outcomes.

Objective

The purpose of this paper is to present the protocol for the Diabetes Learning in Virtual Environments (LIVE) trial.

Protocol

Diabetes LIVE is a two-group, randomized, controlled trial to compare effects of a virtual environment (VE) and traditional website on diet and physical activity. Our secondary aims will determine the effects on: metabolic outcomes; effects of level of engagement and social network formation in LIVE on behavioral outcomes; potential mediating effects of changes in self-efficacy; diabetes knowledge, diabetes-related distress, and social support on behavior change and metabolic outcomes. We will enroll 300 subjects at two sites (Duke/Raleigh-Durham and NYU/New York) who have T2D and do not have serious complications or comorbidities. Those randomly assigned to the intervention group have access to the LIVE site where they can find information, synchronous classes with diabetes educators, and peer support to enhance self-management. Those in the control group have access to the same informational and educational content in a traditional asynchronous web format. Measures of self-management, clinical outcomes, and psychosocial outcomes are assessed at baseline, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months.

Discussion

Should LIVE prove effective in improved self-management of diabetes, similar interventions could be applied to other prevalent chronic diseases. Innovative programs such as LIVE have potential for improving healthcare access in an easily disseminated alternative model of care that potentially improves the reach of self-management training and support.

Keywords: e-health, randomized controlled trial, self-management, type 2 diabetes mellitus, virtual reality

Diabetes is a critical, public health problem amenable to self-management and improved metabolic control. Diabetes self-management training (DSMT), ongoing self-management support by peers and professionals, and strategies for coping with the demands of chronic illness are among the evidence-based strategies for effective diabetes self-management (Funnell & Anderson, 2003; Norris, Engelgau, & Narayan, 2001). Yet, according to claims data for DSMT from 2009–2011, only 6.8% of patients with newly diagnosed diabetes participated in DSMT within 12 months of diagnosis (Li et al., 2014). This demonstrates the need to provide more accessible DSMT, ongoing self-management support, and frequent educational content “refreshers” (Peyrot et al., 2005; Resnick, Janney, Buis, & Richardson, 2010).

Widespread Internet access is bringing the potential of advanced web technologies to all, despite geography and sociodemographic factors (Kaufman, 2010). e-Health programs can link patients to support from peers, particularly others with the same chronic disease, and to providers who can facilitate access to evidence-based information (Kaufman, 2010). Internet interventions for type 2 diabetes (T2D) management have resulted in increased support (Barrera, Glasgow, McKay, Boles, & Feil, 2002; Jackson, Bolen, Brancati, Batts-Turner, & Gary, 2006; Resnick et al., 2010), self-efficacy (Glasgow et al., 2012), patient activation (Lorig et al., 2010), and knowledge (Boren, Gunlock, Krishna, & Kramer, 2006; Jackson et al., 2006; Ramadas, Quek, Chan, & Oldenburg, 2011; Song et al., 2009); decreased health-related distress (Lorig et al., 2010; Williams, Lynch, & Glasgow, 2007) and decreased depressive symptoms (Williams et al., 2007); improvements in glycemic control (Boren et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2006; Lorig et al., 2010; Or & Tao, 2014; Ramadas et al., 2011; Song et al., 2009) and self-management behaviors (Boren et al., 2006; Glasgow et al., 2012; Lorig et al., 2010; Song et al., 2009); and more efficient use of primary care services (Jackson et al., 2006), with decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits (G. Welch & Shayne, 2006). The best DSMT Internet programs provide relevant content, engaging interactive elements, personalized learning experiences and self-assessment tools for monitoring and feedback (Kaufman, 2010; Nijland, van Gemert-Pijnen, Kelders, Brandenburg, & Seydel, 2011; Ramadas et al., 2011). Internet interventions, such as virtual environments (VE), make it possible to access synchronous and asynchronous diabetes education, skill-building activities, and peer/professional support, opening doors to DSMT for many who face barriers (e.g., location, time) attending traditional clinic-based programs.

Virtual environments are real time, computer-generated 3D representations on the Internet where a person interacts with others as an avatar (digital representation of a human) and experiences really being present in the environment due to sensory experiences (Schroeder, 2008). Individuals can interact with other avatars through voice or text chat, and navigate from one location to another. Most health sites within VEs disseminate information and offer support groups. However, there are few simulation scenarios through which people can begin to change behaviors that are transferrable to real life, and few examine the efficacy of this form of intervention (Johnson et al., 2014; Ruggiero et al., 2014). A VE adds functionality for social support and education beyond that of a traditional website format, including synchronous avatar presence and voice communication; placement of educational resources in ‘community locations’ such as the grocery store; and synchronous diabetes education classes.

In our pilot study (Second Life Impacts Diabetes Education & Self-Management [SLIDES]), we built an interactive VE for DSMT that participants reported to be highly useful and usable (Johnson et al., 2014; Vorderstrasse, Shaw, Blascovich, & Johnson, 2014). After six months of participation in the site—by 20 pilot participants—findings showed statistically significant changes in self-efficacy, social support, and foot care; and trends toward improvement in diet, weight loss, and metabolic control (Johnson et al., 2014). Based on these promising findings, the current protocol was developed on a stable, sustainable platform (UnReal Engine 3, Epic Games) that allows for gaming, to test the efficacy of a VE (Diabetes LIVE) as compared to a traditional website format for DSMT.

Protocol

The framework for our VE development in LIVE is based in social cognitive theory, social-ecological support, and computer mediated communications (Vorderstrasse et al., 2014). This theoretical framework is described fully in relation to our SLIDES and LIVE intervention components elsewhere (Vorderstrasse et al., 2014). The primary aim of this trial is to determine the effects of providing DSMT in a VE on diet and physical activity behavior change in adults with T2D compared to a traditional website format. Diet and physical activity are assessed by self-report, validated surveys and activity data is augmented by wireless pedometer (Fitbit®) data. These data will capture changes in minutes of moderate activity and steps per week. Dietary variables, including fat, fiber, and vegetable and fruit intake, will be assessed. Our secondary aims are to: (a) determine the effects on metabolic outcomes (HbA1c, lipid levels, blood pressure, body mass index [BMI]); (b) assess whether level of engagement and social network formation in LIVE differentially impacts behavioral outcomes; and (c) examine the potential mediating effects of changes in self-efficacy, diabetes knowledge, diabetes-related distress, and social support on behavioral and metabolic outcomes.

Design

A multisite, randomized, controlled trial with a longitudinal repeated measures design is being used to evaluate the efficacy of LIVE in terms of health behaviors, psychosocial outcomes or mediators, and metabolic outcomes in adults with T2D over 12 months. We will also explore the sustainability of intervention effects at 18 months. Eligible participants who provide informed consent are randomized to the intervention group (LIVE) or the control group (website) for 12 months. Both are given a Fitbit for physical activity monitoring. Participation requirements include signing in to the assigned site twice weekly for the first three months, followed by discretionary use for the remaining nine months. Follow-up measures are collected at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months for both groups. This frequency and timing is intended to capture the often intraindividual, interindividual and group variability that is likely to occur over time in behavioral outcomes in a nonlinear manner, and to assess clinical outcomes at standard assessment intervals (i.e., every 6 to 12 months) without becoming logistically burdensome for participants (Collins, 2006). We will also be able to determine changes over time during and after the intervention, as modified by relevant covariates, including amount and duration of active participation. This study was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board (IRB; Protocol 00043325) and New York University (NYU) IRB (i14-00897).

Participants and Recruitment

Participants are being recruited at various clinics and through advertisements in the greater metropolitan areas of Durham/Raleigh, NC, and New York City. Social media and digital classified ad sites are also being used. Our target population is adults with type 2 diabetes without regard to duration of disease given that support and ongoing education are necessary throughout the trajectory of this chronic condition. Multisite participation enhances recruitment, sample diversity (race/ethnicity), and evaluation of the intervention across geographic regions.

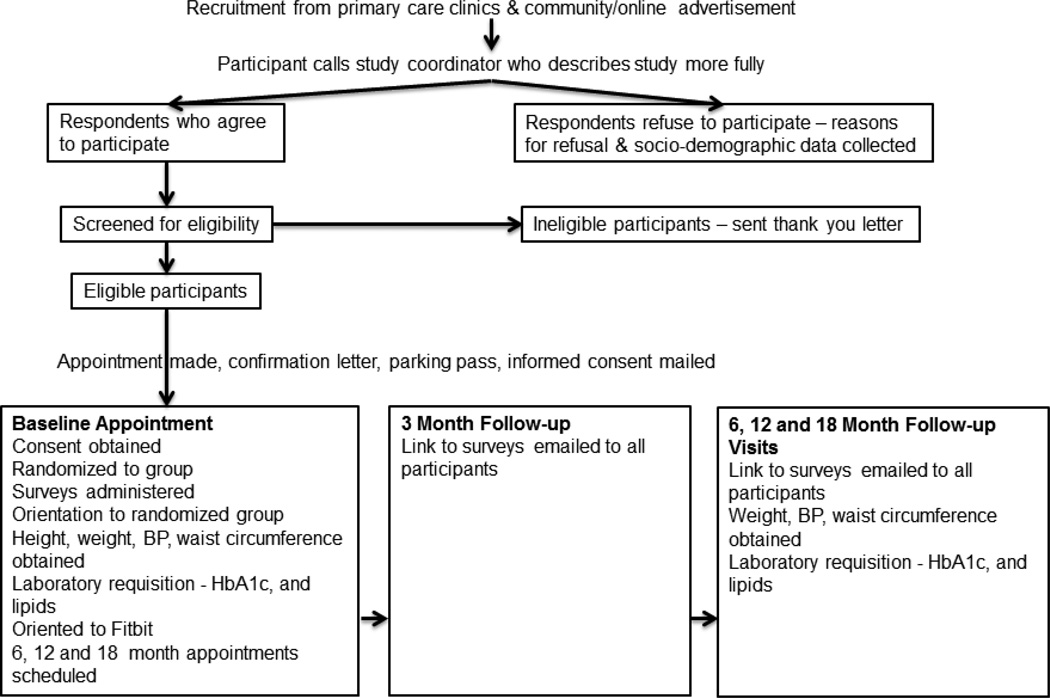

Eligible participants are those with a diagnosis of T2D who: (a) are > 21 years old; (b) are able to read and understand English; (c) have access to a personal computer running Windows with broadband Internet connection in a private location (home) and are able to download the required software; (d) are accessible by telephone; (e) have no pre-existing medical conditions or severe diabetes related complications that would interfere with study participation (i.e., renal failure, Stage III hypertension [BP > 180/110], severe orthopedic conditions or joint replacement scheduled within 6 months, paralysis, bleeding disorders, cancer, or receipt of anti-coagulant medications [warfarin]); and (f) are able to travel to a clinical lab for blood work. In order to determine characteristics of those who decline participation and potential reach of the intervention, we are asking screened participants to respond to basic demographic questions (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, and age) and reasons for declining. Based on our pilot recruitment, those able to be approached or contacted did respond to this request for information. See Figure 1 for recruitment procedures and study flow.

FIGURE 1.

Study schema.

Treatment Conditions

LIVE intervention

The LIVE community was built based on the SLIDES site in collaboration with programmers, graphic designers, and the study team. Classes, resources, and the infrastructure within LIVE incorporate self-management skills and behaviors, as well as personal, cultural, and organizational influences on those behaviors (Table 1). Locations in the VE (e.g., grocery store, pharmacy) offer various ways for participants to utilize informational resources, interact with others, role play to receive feedback on health behaviors, and be awarded for achievements (Table 1). In this interactive community, participants communicate via voice chat, but occasionally use text chat. Diabetes educators facilitate the scheduled classes twice weekly. Participants also communicate via text with peers or educators through a forum. Participants are advised to consult their healthcare provider regarding any medical advice; this disclaimer is found in the site. Question and scenario-based games are offered in the site to utilize the fun quotient and promote further knowledge development. Gamification, such as point scoring (to buy virtual clothes for participant avatars) and competition with others, is being used to engage the participants. Top users of the games, Fitbit, and activity in the site are also posted on leaderboards by their alias study names throughout the site.

TABLE 1.

LIVE Intervention Components for Diabetes Self-Management

| Component | Operationalized | Provides | Need addressed | Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom sessions |

|

|

|

|

| Gym |

|

|

|

|

| Large chain grocery store and convenience store |

|

|

|

|

| Restaurant |

|

|

|

|

| Bookstore |

|

|

|

|

| Pharmacy |

|

|

|

|

| Clothing store |

|

|

|

|

| Forums |

|

|

|

|

| Messages/signs in site |

|

|

|

|

| Games |

|

|

|

|

Note. AADE = American Association of Diabetes Educators; ADA = American Diabetes Association; CDE = certified diabetes educator; DSMT = Diabetes Self-Management Training; NP = nurse practitioner; USDA = United States Department of Agriculture (2011); VE = virtual environment.

Control

Participants randomized to the control group are given access to a password-protected, secure website. The website contains the same educational content (Table 1) found within LIVE for the following: exercise, food items, restaurant menus, and pharmacy and bookstore items. DSMT class content delivered in the LIVE site is provided as recorded modules in the control website. Participants interact with peers and the educators via text in the forum.

Orientation to Treatment Conditions

All participants receive training with the study coordinator when they are given access (i.e., username/password) to either the control website or LIVE site at enrollment. Written instructional materials are also provided. Participants are given headsets with microphone to allow for synchronous voice communication or listening to recorded materials. Avatars for intervention group participants are developed by the study staff and customized by participants. Participants are assigned an alias surname and choose an alias first name for use in the study site including the forums. Three days after the baseline appointment, a follow-up call is placed to participants to address questions about the study procedures and provide a re-orientation to the sites by telephone.

Prevention of Attrition and Decline in Participation

Experience with our pilot intervention (SLIDES), as well as prior Internet intervention studies, indicates that participation begins to drop off at 30 days (Glasgow et al., 2011). We are addressing this by keeping the LIVE community and website dynamic with updated materials monthly and new games every week. Our incorporation of forums in the sites enhances ongoing participation through reciprocity and co-creation, which gives people a sense of ownership (Porter, 2008). Games and gamification are enhancing learning, but also motivating participants to log in regularly.

Those who fail to log in to the assigned site for seven days or longer are sent an email by the study coordinator to encourage reconnection. If there is still no response within seven days, the coordinator calls the participant. Since this is intent to treat analysis, participants will continue to be contacted with updates and for follow-up data collection, unless they formally withdraw. Given the 10% attrition experienced in our short-term pilot study, and the estimates for longitudinal studies, we are assuming approximately 20% attrition in this study.

Data Collection

At baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, survey measures are collected and recorded using an online survey link in REDCap (2015; 1 UL1 RR024128-01) (see Table 2). At baseline, six, 12, and 18 months, a study visit is scheduled to obtain weight, BP, and waist circumference, and provide a requisition to a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)-certified laboratory for a lipid panel and HbA1c. Measurement validity and fidelity is ensured by study staff training, protocol manuals for clinical measures, central participant survey completion in REDCap (2015), central laboratory analysis of metabolic outcomes, and collection of process data from the intervention and control sites. Participants who complete all visits and measures receive $100 and the Fitbit as compensation for their time.

TABLE 2.

Variables and Measurement

| Variable | Description/measure | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Physical activity |

|

Fitbit Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Dietary intake |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Self-management behaviors |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Demographics |

|

Online survey Baseline |

| Metabolic indicators |

|

Study visit Baseline, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Diabetes knowledge |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Self-efficacy |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Diabetes-related emotional distress |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Perceived support for diabetes management |

|

Online survey Baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 months |

| Perceived usefulness |

|

Online survey 3 & 6 months |

| Perceived ease of use |

|

Online survey 3 & 6 months |

| Presencea |

|

Online survey 3, 6, 12 months |

| Co-presencea |

|

Online 3, 6, 12 months |

| Process dataa |

|

Continuous data flow from VE and control site |

| Social influencea |

|

Continuous data collection from LIVE |

Note. ADA = American Diabetes Association; BMI = body mass index; BP = blood pressure; DSMT = Diabetes Self-Management Training; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; HDL = high density lipoprotein; LDL = low density lipoprotein; LIVE = Learning in Virtual Environments; PA = physical activity

LIVE participants only.

Measures

We are collecting tracking and process data (number of logins, time spent in the sites, and interaction with objects) (Blascovich & Bailenson, 2011), diet and physical activity data, metabolic control, as well as mediators of usability and acceptability (social influence, presence, and copresence), and potential psychosocial mediators of intervention effects on metabolic control (Murray, Burns, Tai, Lai, & Nazareth, 2005). Table 2 shows the details of the measures and their validity and reliability.

Sample Size, Power, and Effect Size

Our target enrollment of 300 participants, 150 in each group, accounts for attrition. Approximately half of the participants will be enrolled at each site (Duke and NYU). A stratified, randomization schema is being employed by each site using randomly generated assignments for each site programmed by the study statistician. The random group assignment is hidden in the database programming until the subject is enrolled, but no blinding occurs from the point of assignment. Sample size calculations were based on power to reject the null hypothesis for the primary aim, which states that the trajectories of dietary behavior or physical activity are equivalent for the LIVE and control participants across the 52 weeks following randomization. Our test statistic is the z-test for the parameter in the random effects model associated with the time by treatment interaction. The probability of rejecting this hypothesis in favor of the alternative (the trajectories of the two groups are different) depends upon sample size, effect size, and the type I error rate—which we set to .0167. Bonferroni correction for the multiple outcomes explain this conservative type I error rate. We calculated power using the variance covariance matrix of fixed effects (Diggle, Heagerty, Liang, & Zeger, 2013) for a variety of sample and effect sizes. A moderate effect size was selected based on our pilot data and the literature in behavioral diabetes interventions, and in order to look for clinical significance which would involve achieving at least a moderate effect. Assuming a 20% attrition rate, we will have 240 participants for the primary analysis. With this sample size, we have an 80% probability of rejecting the null hypothesis with effect sizes of .44 or greater.

Data Analysis Plan

The goal of our primary analysis is to quantify the differences between the LIVE and control groups in trajectories of dietary behaviors (fat intake, fruit and vegetable intake), and physical activity over 52 weeks. We will fit a random effects model (Diggle et al., 2013; Levy & Wakim, 2005) to the data with a parameter representing group difference in trajectories over time. The null hypothesis that treatment group trajectories are identical for the two treatment groups will be tested via a z-test The random effects model can handle missing data that may result from attrition. Also, the principle of intention-to-treat analysis will be followed by retaining participants in their originally assigned groups. To determine if metabolic outcomes (HbA1c, lipids, BP, BMI, waist circumference) improve significantly—with a higher rate and sustainability of improvement in the intervention group—we will use a similar model as in the primary aim with these metabolic dependent variables.

To determine if participants with higher levels of engagement and social network formation demonstrate greater improvement in diet and physical activity, we will examine differences in trajectories of dietary behaviors or physical activity between groups of participants who are low or high on measures of engagement. Analyses exploring whether increased self-efficacy, diabetes knowledge, and social support are significant mediators of improvements in dietary and physical activity behaviors, and metabolic outcomes will only be conducted on the outcomes that show significant treatment group differences at 12 months. We will test mediational effects using bootstrap methods (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Discussion

The findings from this study will be among the first steps in determining the efficacy of VEs for diabetes self-management education, and can inform future research on the translation of DSMT interventions into an alternative model of care over the Internet. Although we intend to recruit and reach a broad diverse population with T2D, the sample characteristics will also add to the state of the science in terms of the population reached or interested in this type of Internet-based intervention and potential generalizability. Should LIVE show efficacy in improving self-management of diabetes or metabolic control, similar interventions could be applied to other chronic diseases. This study will also extend the state of the science in terms of measurement of participant engagement in Internet interventions and the resulting effects on behavioral outcomes. This will assist in further work to evaluate the mechanisms of effect of this VE should the RCT reveal its efficacy. Such information could also be useful in personalizing recommendations for appropriate interventions in those with T2D. Finally, use of the Fitbit to track participant physical activity will augment the self-report survey data by providing a form of direct measurement of self-management behavioral outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that this study is funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (1R01-HL118189-01). This study follows the CONSORT guidelines.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration Number: NCT02040038.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Allison A. Vorderstrasse, Duke University School of Nursing, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

Gail Melkus, Research and Florence and William Downs Professor in Nursing Research, New York University College of Nursing, New York, NY.

Wei Pan, Biostatistician, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC.

Allison A. Lewinski, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC.

Constance M. Johnson, Duke University School of Nursing, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC.

References

- American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) AADE 7 self-care behaviors. Diabetes Educator. 2008;34:445–449. doi: 10.1177/0145721708316625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:S13–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailenson J, Swinth K, Hoyt C, Persky S, Dimov A, Blascovich J. The independent and interactive effects of embodied-agent appearance and behavior on self-report, cognitive, and behavioral markers of copresence in immersive virtual environments. Presence. 2005;14:379–393. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Boles SM, Feil EG. Do Internet-based support interventions change perceptions of social support?: An experimental trial of approaches for supporting diabetes self-management. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:637–654. doi: 10.1023/A:1016369114780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich J, Bailenson J. Infinite reality: Avatars, eternal life, new worlds and the dawn of the virtual revolution. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boren SA, Gunlock TL, Krishna S, Kramer TC. Computer-aided diabetes education: A synthesis of randomized controlled trials. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; Paper presented at the AMIA Annual Symposium; Washington, DC.. 2006. Nov, pp. 51–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Eramo-Melkus GA, Wylie-Rosett J, Hagan JA. Metabolic impact of education in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:864–869. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannecker KL, Petro SA, Melanson EL, Browning RC. Accuracy of Fitbit activity monitor to predict energy expenditure with and without classification of activities [Poster]. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise; Presented at the Annual Meeting & 1st World Congress on Exercise is Medicine; Denver, CO. 2011. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989;13:319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Changing office practice and health care systems to facilitate diabetes self-management. Current Diabetes Reports. 2003;3:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Christiansen SM, Kurz D, King DK, Woolley T, Faber AJ, Dickman J. Engagement in a diabetes self-management website: Usage patterns and generalizability of program use. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13:e9. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Kurz D, King D, Dickman JM, Faber AJ, Halterman E, Ritzwoller D. Twelve-month outcomes of an Internet-based diabetes self-management support program. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;87:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner ML, Gary TL. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care: Interactive information technology in diabetes care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Feinglos M, Pereira K, Hassell N, Blascovich J, Nicollerat J, Vorderstrasse A. Feasibility and preliminary effects of a virtual environment for adults with type 2 diabetes: Pilot study. JMIR Research Protocols. 2014;3:e23. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman N. Internet and information technology use in treatment of diabetes. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2010;64:41–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JA, Wakim P. The selection of population average versus subject specific models for analyzing longitudinal data in trials of treatments for drug addiction; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Clinical Trials; Arlington, VA.. 2005. May, [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Shrestha SS, Lipman R, Burrows NR, Kolb LE, Rutledge S. Diabetes self-management education and training among privately insured persons with newly diagnosed diabetes—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR: Morbity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1045–1049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K, Green M, Jernigan VBB, Case S. Online diabetes self-management program: A randomized study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1275–1281. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, Glasgow RE, Schafer LC. Diabetes regimen behaviors: Predicting adherence. Medical Care. 1987;25:868–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E, Burns J, Tai SS, Lai R, Nazareth I. Interactive health communication applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004274.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin K, Melkus GD, Chyun D, Jefferson V. The relationship of spirituality and health outcomes in Black women with type 2 diabetes. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Kelders SM, Brandenburg BJ, Seydel ER. Factors influencing the use of a web-based application for supporting the self-care of patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13:e71. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KV. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561–587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or CK, Tao D. Does the use of consumer health information technology improve outcomes in the patient self-management of diabetes? A meta-analysis and narrative review of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2014;83:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, Snoek FJ, Matthews DR, Skovlund SE. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: Results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabetic Medicine. 2005;22:1379–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. Designing for the social web. Berkeley, CA: New Riders; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadas A, Quek KF, Chan CKY, Oldenburg B. Web-based interventions for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of recent evidence. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2011;80:389–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDCapResearch electronic data capture 2015Retrieved from http://project-redcap.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Resnick PJ, Janney AW, Buis LR, Richardson CR. Adding an online community to an Internet-mediated walking program. Part 2: Strategies for encouraging community participation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12:e72. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero L, Moadsiri A, Quinn LT, Riley BB, Danielson KK, Monahan C, Gerber BS. Diabetes island: Preliminary impact of a virtual world self-care educational intervention for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. JMIR Serious Games. 2014;2:e10. doi: 10.2196/games.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder R. Defining virtual worlds and virtual environments. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research. 2008:1. [Google Scholar]

- Skelly AH, Marshall JR, Haughney BP, Davis PJ, Dunford RG. Self-efficacy and confidence in outcomes as determinants of self-care practices in inner city African-American women with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 1995;21:38–46. doi: 10.1177/014572179502100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Choe MA, Kim KS, Yi MS, Lee I, Kim J, Shim YS. An evaluation of web-based education as an alternative to group lectures for diabetes self-management. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2009;11:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Piliae RE, Fair JM, Haskell WL, Varady AN, Iribarren C, Hlatky MA, Fortmann SP. Validation of the Stanford Brief Activity Survey: Examining psychological factors and physical activity levels in older adults. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2010;7:87–94. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, Kahle LL, Schatzkin A, Kipnis V. Performance of a short tool to assess dietary intakes of fruits and vegetables, percentage energy from fat and fibre. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7:1097–1105. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, Kipnis V, Kahle LL, Schatzkin A. Development and evaluation of a short instrument to estimate usual dietary intake of percentage energy from fat. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2011 Retrieved from http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/

- Vorderstrasse A, Shaw RJ, Blascovich J, Johnson CM. A theoretical framework for a virtual diabetes self-management community intervention. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2014;36:1222–1237. doi: 10.1177/0193945913518993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G, Shayne R. Interactive behavioral technologies and diabetes self-management support: Recent research findings from clinical trials. Current Diabetes Reports. 2006;6:130–136. doi: 10.1007/s11892-006-0024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH. Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabetic Medicine. 2003;20:69–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH. The Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale: An evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:760–766. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Lynch M, Glasgow RE. Computer-assisted intervention improves patient-centered diabetes care by increasing autonomy support. Health Psychology. 2007;26:728–734. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witmer BG, Singer MJ. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence. 1998;7:225–240. [Google Scholar]